Shades of Green: Communicating Ecological Information in Indigenous Languages.

CC BY 4.0 International License

Fúnmiláyọ̀ O.Olúbọ̀dé-Sáwẹ̀

Institute of Technology-Enhanced Learning and Digital Humanities

Federal University of Technology

Akure, Nigeria.

Abstract

"Green economy" is the new buzzword in development economics and environmental protection, a convergence of concepts hitherto thought to be mutually exclusive. Sustainable development is defined asthat which meets the need of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. A corollary of this is the necessity of making those who meet their needs from the soil and water to understand the imperative of using these resources responsibly. In other words, they need to understand and buy into the greening of the economy. This paper reports a small terminological project for translating "green" and related terms, as a contribution to the grassroots popularization of the green economy concept. Theextraction of terms was done manually and concept relationships used in the analysis of source terms prior to term creation, to create morphological series and other paradigms. The major method of term creation used was composition. Fine distinctions in meaningbetween near synonyms were made. This project demonstrates that any language can express any conceivable concept. 105 terms were created, including derived terms.

Keywords: Development Communication, Green, Terminology, Translation

Ìfáàrà-àgékùrú

"Ọrọ̀-ajéẹlẹ́tù" jẹ́ ọ̀rọ̀ titun nínú ẹ̀kọ́ ọrọ̀-ajé onídàgbàsókè àti ìd´àbòlbò àyíká. Ó jẹ́ àkópọ̀ èrò méjì tí wọ́n dàbí aláìbáratan. Oríkì ìdàgbàsókè alálòtọ́nipé ó jẹ́ èyítí ó mójútó àìnì àwọn tówà lọ́wọ́lọ́wọ́, láìṣe ìpalára fún àìnì àwọn ìran ọjọ́-ọ̀la. Àwọn tí wọ́n ń lo wọn ọrọ̀ àbáláyé bí ilẹ̀ àti omi fún àtijẹ-àtimu ní láti mọ̀ ìpọndandan lílò àwọn ọrọ̀ wọ̀nyí ní àlòtọ́, àti l ọ́nà to sàn jùlọ. Kí a kuku sọpé, kí ìsọrọ̀-ajé dí ẹlẹ́tù yé wọn, kí wọ́n sì fọwọ́sowọ́pọ̀ pẹ̀lú àwọn tó ń ṣe agbátẹrù rẹ̀. Àpilẹ̀kọ yìiacute; jẹ́ àbọ̀ iṣẹ́-àkànṣe kékeré kan tó dálérí ṣíṣẹ̀dà ọ̀rọ̀ fún "green" áti áwọn ọ̀rọ̀ tó bá a tan. A ṣe eléyìí láti polongo èrò t´ jẹmọ́ "ọrọ̀-aj ẹlẹ́tù" . Àfọwọṣe ní a fí yọ awọn ọ̀rọ̀ fún ṣẹ̀dá; a sìṣe ìbátan láàárín àwọn ọ̀rọ̀-orísun. A fí eléyìí ṣe ìtòlẹ́sẹẹsẹ àwọn ẹ̀yà- -ọ̀rọ̀ àti awọn ìbátan mìíràn. A wá ṣe àwọn ìyàtọ̀ ọ̀rínkínniwín láàárín àwọn ọ̀rọ̀ onìtumọ̀ afarajọra. Ohun ti àpilẹ̀kọ àbọ̀-ìwádìí yi fihàn nípé bí ọkán-ènìyàn bá lè ró ó, èdè ènìyàn lè sọ ọ́. Ọ̀rọ̀ àpilẹ̀ṣẹ̀dá marún-úndinláàádọ́fà (105) ni iṣẹ́ yìígbé jade, nínú èyí tí àwọn ọ̀rọ̀ atínú- ọ̀rọ̀-mújáde.

Kókó-ọ̀rọ̀: Ìbánisọ̀rọ̀ ajẹmọ́ ídàgbàsókè, Ẹlẹ́tù, Ìṣẹ̀dá-ọ̀rọ̀, Aáyan-ògbufọ̀

1.0 Introduction

This paper investigates connotations and collocation of the adjective green, preparatory to making sense of the concept of "green economy" in the Yorùbá language. Green economy is the new buzzword in development economics and environmental protection, a convergence of concepts hitherto thought to be mutually exclusive. The definition of sustainable development that is most frequently used is found in the 1987 report, Our Common Future, of the United Nations World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED), as "development that meets the needs of the present generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs" (1987: 1). Intergenerational equity, or treating future generations fairly, is the main objective. A corollary of the definition of sustainable development as that which meets the need of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs is the responsibility laid upon linguists to facilitate that those who meet their needs from the soil can understand and discuss the imperative of using land responsibly. In other words, people need to be helped to understand and buy into the greening of the economy.

Grassroots engagement is crucial for the attainment of the 17 sustainable developments goals (SDGs), specific targets that countries adopted on September 25, 2015 to end poverty, protect the planet and ensure prosperity for all. The SDGs are the most recent of strategies by governments to lead their nations out of the prolonged global energy, food and financial crises, with green economy (in its various forms) being proposed as a means for catalysing renewed national policy development and international cooperation and support for sustainable development (https://sdgs.un.org/goals).In a US study, Bruine de Bruin et al. (2021)found that non-specialists did not understand eight terms commonly used by scientists, including sustainable development , carbon-neutral , and adaptation . The problem is compounded for those who have no facility in English or one of the other UN working languages. They are doubly excluded because the information is available only in a foreign language.

Growing international interest in green economy has resulted in a rapidly expanding literature including new publications on green economy from a variety of influential international organisations, national governments, think tanks, experts, and non-government organisations (https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/topics/greeneconomy). Nevertheless, there is no internationally agreed definition or universal principles for green economy, and several interrelated but different terms and concepts have emerged over recent years (such as green growth, low carbon development, sustainable economy, steady-state economy etc.).

There is a proliferation of terms, and there is a need to help people who have facility only in their indigenous languages to make sense of it. This is the justification for this research. Technical terminology is crucial in popularizing development programmes of a technical nature. Bamgbose (1994) proposes five elements that should go into a broader definition of development. He suggests, first, that it should be of a sort that is integrated, with economic development being linked to social and cultural development, and the combination of all three designed to improve the condition of all classes of people in society. His fifth suggestion is that economic development must include mass participation and grassroots involvement in order to ensure that it is widespread and genuine. This requirement for mass participation means more people must be reached with information they can understand and respond to: people must find their own language to articulate the world in their own language, to articulate the world in their own terms and to transform reality in search of their own dreams (Pasquali 1997:33).

More to the point, in recent publications on green economy or green growth, international organisations have begun to address these knowledge gaps and demystify the different concepts associated with green economy. This paper, a report of a small terminology project in the Yor b language of South-Western Nigeria, is a contribution to the demystification. A by-product of this is the revitalization of Yor b , for as terminology devised in this and similar works becomes widely known and used, the utility of the Yoruba language increases. As people find out that they can use their language to do more things, younger generations are encouraged to acquire and use the language, and this would prevent language death.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. A review of issues in terminology development and how the present research is situated in it is briefly presented. This is followed by a review of issues in colour terminology. The methodology of term creation is presented: the manual extraction of terms, the analysis of concept relationships to create morphological series and other paradigms used in the analysis of source terms prior to term creation, the creation of terminology files, and the proposal of equivalents for the source terms.

2.0 Terminology Development

There are various factors that necessitate terminology development. It frequently occurs in large European languages like French, German, or Russian to fill in the gaps brought on by advances in science and technology. According to Beisembayeva and Zharkynbekova's (2014) review of terminology standardization initiatives in four languages English, French, German, and Russian the introduction of new terms into subject areas, particularly in rapidly expanding fields, presents a significant challenge for technical communicators in terms of clarification, definition, and revision of term meanings. Terminology augmentation, which is the most accurate description of this situation, has two strands: generate and validate and extraction from corpora approaches (Iwai et al., 2016). Automatic term extraction can be performed on parallel corpora, such as those published by Tufis et al. (2004) and Lohar andWay (2020), or on comparable corpora, as in Pinnis et al. (2012). In their excellent review of the literature, Iwai et al. (2016) highlight the fact that the majority of the studies make use of contextual information or co-occurrence inside aligned segments of contextual similarity.

The present work belongs to the extraction from corpora strand. Yoruba terminology development has recorded significant progress in the last ten years. Through a partnership between medical experts (medical doctors, nurses, pharmacists, and microbiologists) and language experts, three bilingual glossaries of HIV, AIDS, and Ebola-related terms were published in 2017 for Hausa (Amfani & Ibrahim2017), Igbo (Igboanusi & Mbah2017), and Yoruba (Yusuff, Adetunji &Odoje2017). The bilingual glossaries provide authoritative definitions and concise explanations for a variety of terms used in HIV, AIDS, and Ebola discourses as well as practices and medical issues connected to the epidemics. They were specifically developed with medical professionals and patients in mind. The entries cover a wide range of topics, including ailments, signs and symptoms, drugs and drug administration, illness management and control, techniques and equipment, health service organizations, therapies, testing and screening, preventive behaviour, and procedures.

The glossary's primary goal was to improve communication between the Hausa-, Igbo- and Yoruba-speaking communities and the healthcare professionals who care for them, to facilitate interaction and lessen the negative perceptions and attitudes about the disease conditions.

Other works include terminology of football (Komolafe, 2020a), human diseases (Olupona, 2020), and agriculture (Komolafe, 2020b), which attempted to revise some terms earlier published. He notes rightly that pest ≠ k k r ayọnilẹ́nu, as NERDC has it, as a pest is not necessarily an insect. He proposes four candidate terms: agb gun-toko (lit. attacker of farm); as pal raf ko (lit. agent of harm to farm); ayọkolẹ́nu (lit. troubler of farm); and abokojẹ́ (lit. destroyer of farm).

The Colour Green

Colour refers to that aspect of an object that may be described in terms of hue, lightness, and saturation, associated with the visible wavelengths of electromagnetic radiation, which stimulate the sensor cells of the eye (Nassau, 2022). This definition may lead one to conclude that colour can be identified by a set of objective criteria. Berlin and Kay (1969) conclude that there are similarities in the ways that different languages with the same number of basic colour terms (BCTs) carve up the colour space, and that there is an order in which languages acquire BCTs. In a revised theory, colour term development is viewed as re-categorisation rather than addition (Kay, Berlin et al., 2009).

Other research shows that languages categorise colour in different ways. In some North American, Mesoamerican Indian and African languages, there is a basic megacategory grue , which covers the colour region categorised by English speakers as green and blue (Hardin, 2013). In Russian, blue is a megacategory: covering goluboi, light blue , and sinji, dark blue . In addition, there are languages that have no words for the concept colour , including the Australian language Warlpiri (Wierzbicka, 2008) and Candoshi, spoken by an indigenous people from the Upper Amazon (Surrall s, 2016).

Green is formed as a mix between two primary colours, blue and yellow. Green is a significant colour because it occurs in profusion in nature. It is therefore not strange for it to find its way into the metaphors we create to make sense of the world around us. Green is said to stand for nature, spring, and rebirth , it is the colour of life, renewal, and nature, is associated with meanings of growth, harmony, freshness, safety, fertility, and environment. As the emblematic colour of Ireland, green represents the vast green hillsides, as well as Ireland s patron saint, St. Patrick, and in the Nigerian national flag, it represents agricultural productivity. Green altar cloths/vestments are used in standard Catholic masses in between seasons of celebration and special observances, being indicative of plants and trees, representing growth and hope for life eternal (http://peopleof.oureverydaylife.com/catholic-altar-cloth-colors-2303.html).

Many metaphorical constructs that involve the colour green are culture-specific. According to colour psychologist Smith, green has the following associations in different parts of the world: in Iran, green, alongside blue-green and blue are symbolic of paradise; in Japan, green is regarded as the colour of eternal life (Smith, 2017). In Aztec culture, green was the colour of royalty on account of the quetzal plumes used by the Aztec chieftains and in the Scottish highlands, green was worn as a mark of honour. Green also has close ties with Islam, and Prophet Mohammed is said to have worn a green cloak and turban (https://lammuseum.wfu.edu/exhibits/virtual/faith-five-world-religions/islam/)

From the perspective of using colours for effective messages, it is useful to be sensitive to both universal and cultural connotations of colours since ethnic and cultural backgrounds inspire specific colour associations. For instance, in many western countries, green symbolizes good luck (shamrock), youthfulness, ecology, and fertility. However, in China green stands for disgrace and exorcism; in the USA it is associated with money and wealth but also with envy and poison; in many South American cultures it represents death. Inthe Middle East green is the colour of Islam; but in parts of Indonesia it is forbidden. (http://commdesign.ca/tag/colour-connotations/).

A related issue is that of colour hues. Green has been identified as having the following shades: emerald, sea green, sea foam, olive, olive drab, pea green, grass green, apple, mint, forest, lawn green, lime, spring green, leaf green, aquamarine, beryl, chartreuse, fir, kelly green, pine, moss, jade, sage, yellow-green, sap, viridian. In Nigeria, one can get wedding invitations requesting guests to wear army-green or GLO-green. Different shades of green may signify different things: dark green represents greed, ambition, and wealth, while yellow-green stands for sickness, jealousy, and cowardice, and olive green is the traditional colour of peace.

These colours show up in metaphors, some with positive and others with negative connotations. Someone with a green thumb (US) or green fingers (UK) has an unusual ability to make plants grow. Performers relax in a green room , projects get the green light on which they might get to spend the greenback (a US dollar bill) even though they might employ greenhorns (trainees/novices). From Psalm 23 has come the metaphor of greener pastures and grass is greener , a reference to a place of better opportunities. Contrariwise, a green-eyed monster is a jealous person and is usually green with envy , and someone who is green around the gills has a sickly or pale appearance. Someone who turns green , looks pale and ill as if s/he is going to vomit but when they go green , they make changes to help protect the environment, or reduce waste or pollution.

Green in the Yorùbá Language

Green has several equivalents in the Yoruba language. For the concept unripe , the preferred designation is 'dudu', as in the proverb, ọ̀gẹ̀dẹ̀ dúdúkò yáa bùṣán; ọmọ burúkú kò yáa lù pa (green plantains cannot easily be eaten raw; a recalcitrant child cannot be easily flogged to death). In biblical translation, two other terms are used in addition to dudu. For example, green pastures (Psalm 23:2) is translated: papa oko tutu (BíbálíMímọ́, Bibeli Ìròyìn Ayọ̀), green plants (Psalm 37:2) is eweko tutu, green leaf (Proverbs 11:28) is koriko tutu. Other terms are descriptive of freshness. For example, green in Job 8:16 is ti a bomirin (Bibeli ÌròyìnAyọ̀), or tutu yọ̀yọ̀ (BíbélìMímọ́) and green figs (Songs of Solomon 2:13) is èsoọ̀pọ̀tọ̀ tuntun. None of these equivalents for green conceptualize a colour.

Yorùbá basic colours are dudu (black, dark), pupa (red) and funfun (white). In recent times, equivalents have been derived for other colours. For example, Odetayo (1993) presents the following equivalents for the colour spectrum: red is ẹpọ́n, orange is ọsàn, yellow is ìyeyè, green is ewé, blue is oféfe, indigo is aróand violet is èsè-àlùkò. Other proposed equivalents for green are àwöewáko/ aligà (https://www.abibitumikasa.com); ewé; aláwọ̀ ewéko, aláwọ̀ ọ́bẹ́, dúdú, àwoewé, òdò, àigrave;pọ́n, àìdẹ́, tutu, ọbẹd&oagrave; (https://glosbe.com/en/yo/red-green-blue), àwọ̀ obedo (www.awayoruba.com/forum) àwọ̀ ewé (polymath.org/yoruba_colors.php).

The problem is that these equivalents would not be appropriate in concepts like "green revolution", "green growth", or "green economy". For example, "green growth" cannot be rendered as ìdàgbàsókè aláwọ̀ ewéko, ìdàgbàsókà dúdú or ìdàgbàsókè tutú. Ìdàgbàsókè ewé would even be worse because development does not contain the feature plus colour. The nonsense sentence used in elementary linguistics classes comes to mind: Colourless green ideas sleep furiously . Since these equivalents obviously do not capture the concept of green that is required, a concept analysis is called for, and the creation of a new set of designations for green and other related terms.

3.0 Research Method

3.1 Generation of Source Terms

This is a two part process: term identification and term extraction. The first part involved the recognition and selection of designations. Basically, this meant going over texts and choosing the terms to be retained for study and possible dissemination. The basic skill needed here is the recognition of the terminological units. In specialized languages, a term is a linguistic unit made of a single word or a word combination, and is usually associated with the same conventional definition when used by speakers of a given specialized language, including symbols, chemical or mathematical formulae, official titles, etc. (Gorodetsky 1990). The second part involved going through a corpus in order to identify concepts and their designations (terms, abbreviations), recording them and noting any relevant information about a concept such as definitions, contexts, and usage labels. In this work, source terms were taken from ten online general purpose texts dealing with green economy[i]. The terms were manually extracted after manual highlighting the beginning and the end of each term's context so the data could subsequently be transcribed on a terminological record for analysis. A total of 143 terms were initially extracted in this manner.

3.2 Concept Analysis

Concepts enter into different kinds of relationships among themselves. The relationships are of two kinds, namely, hierarchical and associative. Hierarchical relationships are sub-divisible into two: generic-specific and part-whole. All these relationships were used to structure knowledge and assign source terms to paradigms to ensure concept-designation monosemy, create generic-specific and associative morphological series, following Olubode-Sawe (2010). As Odetayo (1993:1) suggested, near synonymous terms were treated together by assembling synonyms in the target language and matching them. Existing terms were sought from the following texts with the following short forms: Quadrilingual Glossary of Legislative Terms (QG), Yoruba Modern Practical Dictionary (YMPD), A Dictionary of the Yor b Language (DYL) and A Yoruba Vocabulary of Building Construction (YVOC).

Where an existing suitable equivalent could not be found, a term was devised for the source term, based on terminological definitions extrapolated from definitions taken from online general purpose dictionaries.

4.0 Results and Discussion

From the 10 texts studied, green occurred in such noun phrases as green buildings , green business , green economy , global green economy , green economy policies , green economy programmes , green growth , green industry , green industry sector , green investment , green job , green market , green options , green sectors , green technologies , greener policies and regulations , and greenhouse gas emissions . It also occurred as complement of verbs: as in be green , make green , being green , go green , considered green .

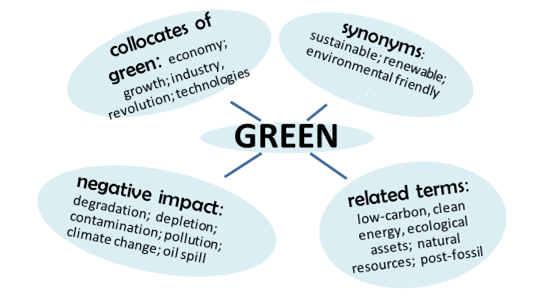

From six selected definitions of green terms , some recurring meanings were isolated: environmental friendliness , and a concern with sustainability and with natural resources . It was decided that designations for green would focus on these meanings. Related concepts found in the corpus include: bioenergy, carbon, climate change, degradation, depletion of ecological assets, ecology, environment, renewable energy and sustainability. It was decided to focus on these concepts that are somewhat related to the environment, and propose designations for these key terms, and thereafter generate terms for related concepts. The relationships were highlighted using a concept diagram, shown in Figure 4.1 below.

Figure 4.1: Concept Diagram of GREEN and Related Terms.

After an understanding of relationships between the concepts for which terms were to be created, terminological information was recorded in terminology case files (TCF)which show the ISO 639-1 language code (en for English and yo for Yor b ); then the term and its word class in brackets. On the next line is a terminological definition (DEF), the source of the term, if borrowed from another language or its morphological composition, if an indigenous term (←), synonyms or variants (SYN) and any equivalents (EQ). Observations, in form of comments by specialists (OBS) and References (R) indicating the textual sources, where available, are also included. The TCFS for green, biodiversity and habitat are presented below. The slot for equivalent is still empty because no term has been found for green.

|

En |

GREEN (ADJ) |

simple term, ADJ |

|

DEF

SYN |

environmentally responsible and resource-efficient; producing no negative impact the local or global environment

renewable; sustainable |

|

|

Yo |

Lọ́nà to bọ̀wọ̀ fúnàyíká, tíkòsì fi àlùmọ́nìṣòfò; ti ko si mu ìpalárabaàyíká, yálàtiagbègbèkantàbíkáríayé. |

|

|

EQ |

? |

|

|

OBS |

Terms must be created separately for synonyms |

Figure 4.2: Terminology Case File for Green

|

n |

BIODIVERSITY (N) |

complex term, N |

|

DEF

SYN |

the variety of plant and animal life in the world or in a particular habitat, a high level of which is usually considered to be important and desirable all species and living things on Earth or in a specific ecosystem

biological variety; ecological diversity (narrower); ecosystem diversity (narrower) |

|

|

Yo |

bíonírúurúewékoàtiẹranko(ohunoníyè) ṣepọ̀ tóníàgbáyétàbániibùgbé-àbáláyé |

|

|

EQ |

? |

|

|

OBS |

Terms must be created separately for synonyms |

Figure 4.3: Terminology Case File for Biodiversity

|

En |

HABITAT (N) |

simple term, N |

|

DEF

SYN |

The conditions suitable for an organism or population of organisms to live and thrive

natural environment; natural home |

|

|

Yo |

àwọnibàtí ó fàyègb´oníyètàbíàgbájọpọ̀ oníyèlátigbéàtilátipọ̀ síi |

|

|

EQ |

ibùgbé-àbáláyé |

|

|

OBS |

synonyms are merely descriptive; terms not needed |

Figure 4.4: Terminology Case File for Habitat

After the creation of terminology case files, the next step was to generate candidate terms as equivalents. First, existing dictionaries and terminological works were scanned to see if appropriate terms existed for any of the source terms. Table 4.1 shows the results of the matching of existing terms for three concepts.

Table 4.1: Matching of Existing Terms for Near Synonyms

|

|

QG |

YM |

DYL |

YVOC |

|

Contaminate |

---- |

latifiabuku kan nnkan |

ba...je |

---- |

|

contaminant |

asọdidibajẹ |

---- |

---- |

---- |

|

Contamination |

isọdidibajẹ |

---- |

Ibaje |

|

|

Degrade |

---- |

ẹ̀lọ̀ |

re...sile; ye nipo |

---- |

|

Degradation |

---- |

---- |

---- |

---- |

|

Biodegradation |

---- |

ẹ̀lọ̀ ẹ̀l - y |

---- |

---- |

|

Pollute |

---- |

|

ba...je; so di aimo |

|

|

Pollution |

Ìtorósí |

ibayikajẹ |

ibaje; aimo; eeri |

ìsọdeléèérí |

|

atmospheric pollution |

---- |

---- |

---- |

ìsojú-sánmọ̀-deléèérí |

As can be noticed, there are many gaps, representing concepts for which no terms currently exist. In addition, they are concepts for which the same terms are used. It is therefore necessary to propose terms for these gaps and ensure that they are used in a consistent manner, with an eye on the derivations that may arise. For example, degradation occurs as a source term in data, but not degrade, degradable, biodegradable, non-biodegradable or biodegradation. However, it is necessary that whichever term is chosen or created for degradation should be of a kind that will generate the base morpheme degrade and all its derivations.

Most of the terms in this work were created by composition. Composition is the process of combining morphemes, words, or even phrases from a language to produce new expressions that signify new concepts.(Olubode-Sawe, 2013). The three compositional strategies of description, translation, and idiomatisation make use of these combinations. Composition by description includes describing a tangible object while mentioning a few of its essential features, which may include the object's function or application, its construction or use, its physical appearance, its behaviour, and any other peculiar characteristics. The second method of composition is loan translation. This requires morphemes from the source term to be translated into the target language. Each morpheme in a borrowed phrase therefore has an equivalent in the recipient language. Like the second method of composition, idiomatisation, which also combines morphemes, words, and phrases, the meaning of the word or term formed does not come from the combined meanings of its combining components. Rather, the combining units are used in puns, euphemisms, and other ways that show innate intelligence. Three Yoruba instances are given by Olubode-Sawe (2010): adéedádì, àrùngbajúmọ̀ and bọ́síkọ̀rọ̀. In adéedádì, adé, ("crown"), and dádì, ("daddy"), are combined in adéedádì (literally, "daddy's crown") for "condom".

Table 4.2 shows three concepts describing negative impacts on the environment and their derivations.

Table 4.2: Creation of Terms for Near Synonyms

|

Base Source Term |

Derivations |

Proposed Equivalents |

Another equivalent? |

|

CONTAMINATE |

|

sọ...dàìmọ̀; |

|

|

|

contaminated |

àsọdàìmọ̀ |

|

|

|

contaminant |

asọdàìmọ̀ |

|

|

|

Contamination |

ìsọdàìmọ́ |

|

|

DEGRADE

|

|

díbàjẹ́ (non-trans) sọdìdíbàjẹ́ (trans) wópalẹ̀ (trans./non-trans) |

|

|

|

Degradation |

ìsọdìdíbàjẹ́/ìwópalẹ̀ |

|

|

|

Degradable |

aṣeéwópalẹ̀ |

|

|

|

biodegradable |

aṣeéfohun-abẹmiwópalẹ̀ |

aṣeéfoníyàwópalẹ̀ |

|

|

non-biodegradable |

al´ìṣeéfohun-abẹmiwópalẹ̀ |

aláìṣeéfoníyèwópalẹ̀ |

|

|

biodegradation |

ìfohun-abẹmiwópalẹ̀ |

ìfoníyèwópalẹ̀ |

|

POLLUTE |

|

toró...sí |

|

|

|

Pollution |

Ìtorósí |

|

|

|

atmospheric pollution |

ìtorósíoju-sánmọ̀ |

|

|

|

environmental pollution |

ìtorósíàyíká |

|

In creating terms for green and related terms, it became obvious that the semantically transparent options could not be used for green because the concept of green economy itself involves metaphorical construal. This matter had been earlier raised when it was pointed out that ìdàgbàsókè aláwọ̀ ewéko, ìdàgbàsókè dúdú or ìdàgbàsókè tutù would not be appropriate equivalents for "green growth". From the definitions of "green" terms, some distinguishing characteristics appeared and were grouped under three as shown in Table 3. In creating the term for bio- (living), the options were abẹ̀mí (having a spirit) or oníyè (having life). It is conceivable that plants have life, but not spirits. This is subject to debate: with questions about whether plants have souls or consciousness. Marder 2011 addresses the issue of plant soul, and a 1968 experiment by Cleve Backster seems to support that plants have feelings. Plants react to pain and seem to be able to react to the thought of being harmed. I have side-stepped the issue, by selecting oníyè, using that term in all bio- constructions.

Table 4.3: Green and Related Terms

|

Definitions of green |

Environmental friendliness |

sustainability |

Natural |

|

environmentally responsible and resource-efficient |

environmentally responsible |

resource-efficient |

- |

|

no negative impact is made on the local or global environment |

no negative impact on environment |

- |

- |

|

reducing environmental risks and ecological scarcities, aims for sustainable development without degrading the environment |

without degrading the environment |

sustainable |

- |

|

uses natural resources in a sustainable manner |

- |

sustainable |

natural resources |

|

environment friendly |

environment friendly |

- |

- |

|

conservation of natural resources environmentally conscious |

environmentally conscious |

conservation |

natural resources |

Based on the information in Table 4.3, candidate target terms were generated for green and back-translated into English, as shown in Table 4.4 below.

Table 4.4: Candidate Target Terms

|

Candidate Target Term |

Back Translation |

Remarks |

|

aláilolẹ̀ṣá, |

that does not use the soil till it loses its nutrients |

|

|

aláibalẹ̀jẹ́, |

that does not spoil the soil |

|

|

aláijẹlẹ̀run, |

that does not consume the soil |

|

|

alálòtúnlò, |

that can be used and re-used |

|

|

alálòpẹ́, |

that can be used for long |

|

|

alálòtọ́ |

that can be used in the right manner OR that can be used in a long-lasting manner |

intentional ambiguity * long lasting * rightful use |

|

asàyíká-dọ̀tun |

that renews the environment |

|

|

abayìíká-dọ́rẹ̀ẹ́ |

that makes friends with the environment |

|

Green is of course all these and more. The main task was to find a culturally relevant Yorùbá expression that will recall the characteristics of retained fertility, abundance, comfort. (These candidate terms will not be wasted but be used in the definition of the term.) The proposed term is ilẹ̀-ẹlẹ́tùlójú. This phrase is traditionally used to describe soil that is fertile; as a matter of fact, it calls up associations of life, renewal, and nature, growth, harmony, freshness, safety, fertility, and environment; all the associations of green, except the colour. Previous uses of ẹlẹ́tùlójú includes ìlú-ẹlẹ́tùlójú in the anthem of Áwẹ́ town in Ọ̀yọ́ State, and 'Wanihin, wanihin, si'lẹ̀-ẹlẹ́t&eactue;lùjú, in the refrain of CAC Hymn 956. Ilẹ̀-ẹlẹ́tùlójú is a 'green land', the noun-head has been deleted and the qualifier ẹlẹ́tùlójú retained as the equivalent for green. Examples of ẹlẹ́tùlójú and its collocates are: ib&actute;-ìkọ́lé ẹlẹ́tùlójú (green building), ilana ọrọ̀-ajé ẹlẹ́tùlójú (green economy policies), ìdàgbàsókè ẹlẹ́tùlójú (green growth) and ìdókòwòẹlẹ́tùlójú (green investment). Other terms include ìsọ-tẹ́dátàyíká-dìdíbàjẹ́ (ecological degradation) àìfàlùmọ́nìṣòfò (resource efficiency), àwùjọasàifàkạ̀kù-oníyèsagbára (post-fossil society), and àwọnorísunalálòtúnlò (renewable sources). One hundred and five designations were created in this manner.

An entry for green economy would therefore be as follows:

|

En |

Green economy (NP) |

simple term, N |

|

DEF

|

A system of production in which activities are carried out in an environmentally responsible and resource-efficient manner, with little or no negative impact on the local or global environment |

|

|

Yo |

ọrọ̀-ajé ẹlẹ́tù |

|

|

Oríkí |

Ètò ìsenǹkan-jáde nínú éyí tí àọn àgbéṣe jẹ́ abọ̀wọ̀fáyìíká àti aláìfàlùmọ́nìṣòfò, ti kò sì ṣe ìpalára (púpọ̀) fún àyíkà, yálà ní itòsí tàbí káríayé |

Figure 4.5: Terminology Case File for green economy

The terms were shared via WhatsApp with a group of ten competent Yoruba speakers: three linguists, two engineers, one applied geologist with special interest in ecology, one cooperative official who attends a Yoruba-speaking church and ministers in the medium of Yoruba and two others. Their suggested modifications are presented in bold red letters and asterisked. A strikethrough indicates that the suggestion is problematic in some way. For example, "omi-ilẹ̀ àti ilẹ̀ tó ti dàìmọ́" is not only too long, it lacks the agentive morpheme "sọ di-". The point of contamination is not that something is unclean, but has been made unclean by an external agency.

5. 0 Conclusion

This paper set out to do two things: first, to show that we need to carry monolingual users of our indigenous languages along in development efforts. A revolution involves mass action, and English-speaking scientists in their rarefied laboratories and technical sessions of conferences cannot constitute the critical mass needed to start or sustain a revolution. The sustainable development goals must be owned by the masses; all things green must be demystified so that people can participate. Ondo State Oil Producing Area Development Commission (OSOPADEC) commissioned indigenous language versions of their vision and mission in 2017. In preparing the Vision, Mission and Core Values of the Commission, ecological responsibility was listed as a core value. But what does it mean? The phrase was unpacked in the following manner:

Ecological Responsibility

Using natural capital in a resource-efficient and sustainable manner, as trustees of present and future generations

Ìbọ̀wọ̀ fún Àyíká

Lílo àwọn ọrọ̀ àbáláyé ní àyíká l'ọ́nà to sàn jùlọ, ti yóó sì ní àlòtọ; gẹ́gẹ́ bí àlámòójútó ogún àwọn ìran òní àti àrọ́mọdọ́mọ wọn

OSOPADEC Vision and Mission

The second goal was to show that it can be done. Therefore terms were created by locating, evaluating, using, transforming, and/or modifying existing resources, relying on the compositional strategies of description, translation, and idiomatisation. The analysis of word meanings and semantic fields was linked to the analysis of the characteristics of specialized concepts (to be designated) and the disciplinary knowledge structure formed by the links between the concepts. Devising a designation for the key term, green economy involved metaphorical construal, since the source concept itself is a metaphor. The task was to select an existing metaphor that fit, rather than create a new one. Nevertheless, composition still featured in the process.

In attaining the second goal, what is required is the will, the cooperation of technical and language experts, and enough respect for our indigenous languages to know that if we can conceptualize an idea, our languages can express it. The terms may not sound very smooth to start with, and there are times that it will seem cheaper to just keep the information conveniently in foreign languages. Respect for our indigenous languages must, therefore, be accompanied by a respect for the rights of those whose only way of making sense of the world is in these languages.

The first goal of this paper was to demonstrate that terminology development can contribute significantly to development communication. The second goal was to demonstrate the feasibility of creating terms using existing resources and compositional strategies. The analysis of word meanings and semantic fields was linked to the identification of specialized concepts and the disciplinary knowledge structure.

Postscript: 2022[1]

OSOPADEC commissioned me to do the Yoruba version of their vision and mission in 2017. I checked the website of OSOPADEC in 2022. I did not find the indigenous language versions there. So, I called the consultant. He informed me that regrettably, they did not upload the indigenous language versions. In other words, even after terms have been created, users (who may have commissioned the terms) are reluctant to popularise them. We can take the horse to the river, but we cannot force it to drink.

References

Ile alafia kan wa, ti 'lekun re si s'ile . Christ Apostolic Church Gospel Hymn Book Hymn 956. Available at https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.adediranife.cachymn

Amfani, A. H., & Ibrahim, G. (eds) 2017. English-Hausa glossary of HIV, AIDS and ebola related terms. Ibadan: University Press PLC.

Antia, B. E (2000).Terminology and language planning: An alternative framework of practice and discourse. Amsterdam: John Benjamins

Antia, B.& Ianna, B. (2016). Theorising terminology development: Frames from language acquisition and the philosophy of science.Language Matters, 47:1, 61-83, DOI: 10.1080/10228195.2015.1120768

wọ̀ni Yoruba / Colours in Yoruba. Retrieved June 9, 2017 from www.awayoruba.com/forum

Bamgbose, A (1994). Pride and prejudice in multilingualism and development . In R Fardon& G Furniss (Eds.) African Languages, Development and the State. London & New York: Routledge. 33-43

Basic Colors in Yoruba. Retrieved June 9, 2017 from https://www.abibitumikasa.com

Backster, C (1968). Evidence of a Primary Perception in Plant Life. International Journal of Parapsychology, 10 (4). 329-348

Beisembayeva, G & Zharkynbekova, S. (2014). Development trends of technical terminology in the Germanic Languages Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 143. 487 490

Berke, P., & Manta, M. (1999). Planning for Sustainable Development: Measuring Progress in Plans. Lincoln Institute of Land Policy. http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep18489

Bibeli r y nAyọ̀ (2005). (The Holy Bible in Yoruba Common Language). Lagos: The Bible Society of Nigeria

B b l M mọ́ (2005). Revised from the Holy Bible in Yoruba, 1900 edition. Chicago: Bible League

Bruine de Bruin, W., Rabinovich, L., Weber, K., Babboni, M., Dean, M. &Ignon, L. (2021) Public understanding of climate change terminology. Climatic Change, 2021; 167 (3-4) doi: 10.1007/s10584-021-03183-0

Brundtland, G.H. (1987) Our Common Future: Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development. Geneva, UN-DokumentA/42/427. http://www.un-documents.net/ocf-ov.htm

Catholic Altar Cloth Colors. Retrieved June 9, 2017 from http://peopleof.oureverydaylife.com/catholic-altar-cloth-colors-2303.html.

Dictionary of the Yoruba Language, A (2005). Ibadan: University Press PLC.

Fakinlede, K J (2003).Yor b Modern Practical Dictionary (Yoruba English/ English Yoruba). New York: Hippocrene Books Incorporated.

Gorodetsky, B Y (1990) Cognitive Aspects of Terminological Phenomena . In Proceedings : Second International Congress on Terminology and Knowledge Engineering, 2 4 October 1990, University of Trier, Germany. Ed. Hans Czap & Wolfgang Nedobity. Frankfurt Main: INDEKS Verlag.

Green Economy. Retrieved June 9, 2017 from https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/topics/greeneconomy,

Guidelines for Terminology Policies: Formulating and implementing terminology policy in language communities, (2005). Prepared by Infoterm. Paris: UNESCO.

Hardin, C.L. (2013). Berlin and Kay Theory. Encyclopedia of Color Science and Technology. New York: Springer Science+Business Media

Igboanusi, H., & Mbah, B. M (eds.) (2017). English-Igbo glossary of HIV, AIDS and ebola-related terms. Ibadan: University Press PLC

Iwai, M., Takeuchi, K., Kageura, K. & Ishibashi, K. (2016). A Method of Augmenting Bilingual Terminology by Taking Advantage of the Conceptual Systematicity of Terminologies. In Proceedings of the 5th International Workshop on Computational Terminology (Computerm2016), pages 30 40, Osaka, Japan. The COLING 2016 Organizing Committee.

Kay, P., Berlin, B., Maffi, L., Merrifield, W.R., Cook, R.: (2009) The World Color Survey. CSLI Publications, Stanford

Komolafe, O. E. (2020a) The place of indigenous languages in the development and teaching of agriculture in Osun State, Nigeria LWATI: A Journal of Contemporary Research, 17(4), 41 -52.

Komolafe, O. E. (2020b) Developing football language in Yor b Inkanyiso: Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences 12(2) 178-193

Lohar, Pintu & Way, Andy (2020) Parallel data extraction using word embeddings. In: NLPTA 2020 : International Conference on NLP Techniques and Applications, 28-29 Nov 2020, London, UK (Online). Computer Science & Information Technology. 10 (15). AIRCC Publishing Corporation. 2020 pp. 251-267., 2020

Marder, Michael (2011) Plant-Soul: The Elusive Meanings of Vegetative Life. Environmental Philosophy, 8 (1). 83-100.

Nassau, Kurt. Colour . Encyclopaedia Britannica, 7 Sep. 2022, https://www.britannica.com/science/color. Accessed 10 October 2022.

Odetayo, J A (1993) Yoruba Dictionary of Engineering Physics. Lagos: University of Lagos Press

Olubode-Sawe, F. O (2013). Strategies of Composition in Yoruba Plant Nomenclature . In O-M Ndimele, , L. C. Yuka & J. F. Ilori (Eds.) Issues in Contemporary African Linguistics: A festschrift in honour of Ọl d l Aw b l y . 237-256

Olubode-Sawe, F. O. (2010). Devising a Yor b Vocabulary for Building Construction . PhD Dissertation, Adekunle Ajasin University, Akungba-Akoko, Nigeria.

Olupona, O. (2020). Devising Yor b terminology for human diseases. Afribary. Retrieved from https://afribary.com/works/ma-thesis-copy-2

Onyango J O (2005). Issues in National Language Terminology Development in Kenya. Swahili Forum 12. 219-234

Oriki Awe - Awe Town's Praise Song. Retrieved June 9, 2017 from https://web.facebook.com/notes/2634312596832002/

OSOPADEC Vision and Mission (Trilingual Version) (MS)

Owolabi, K (2004). Developing a strategy for the formulation and use of Yoruba legislative terms. In K. Owolabi& A. Dasylva (Eds.),Forms and Functions of English and Indigenous Languages in Nigeria. Ibadan: Group Publishers.

Pasquali, A (1997): The Critical Avant-Garde . Journal of International Communication, 4 (2), 29-45.

Pinnis, M., Ion, R., Ştefănescu, D., Su, F., Skadiņa, I., Vasiļjevs, A. & Babych B. (2012). ACCURAT toolkit for multi-level alignment and information extraction from comparable corpora. Proceedings of the 50th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics. 91 96,

Project Augustine (nd) Plant theology: Do plants have a soul? https://projectaugustine.com/science-and-theology/cognitive-neuroscience/plant-theology-do-plants-have-a-soul-plant-neurobiology/

Quadrilingual Glossary of legislative terms (English, Hausa, Igbo, Yoruba), (1991). Lagos: Spectrum Books Limited (for Nigerian Educational Research and Development Council).

Red-green-blue in Yoruba English-Yoruba dictionary. Retrieved June 9, 2017 from https://glosbe.com/en/yo/red-green-blue

Smith, K. (2004) Colour Symbolism and the Meaning of Green. Retrieved June 9, 2017 from http://www.sensationalcolor.com/color-meaning/color-meaning-symbolism-psychology/all-about-the-color-green-4309#.WTpDJpt0O2d

Surrall s A. (2016). On contrastive perception and ineffability: assessing sensory experience without colour terms in an Amazonian society. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute22 (4). 962-979

Thirumalai, M S (2003): Language in science. Language in India Series, Volume 3. Available at http://www.languageinindia.com/

True colours, is that why I love you? Retrieved June 9, 2017 from http://commdesign.ca/tag/colour-connotations/

Tufiş D., Barbu A. M. & Ion, R. (2004)Extracting multilingual lexicons from parallel corpora. Computers and the Humanities.38, (2) 163-189.

Wierzbicka, A. (2008). Why there are no colour universals in language and thought. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 14 (2) 407-425

Yoruba Colours. Retrieved June 9, 2017 from www.polymath.org/yoruba_colors.php

Yusuff, L. A., Adetunji, A., &Odoje, C. (eds.) (2017) English-Yor b glossary of HIV, AIDS and ebola-related terms. Ibadan: University Press PLC

Appendix: PROPOSED YORÙBÁ TERMS FOR GREEN AND RELATED TERMS

(The appendix is not included in the .html version of this article - for full access, please refer to the .pdf version of the article.)