The introduction and acceptance of Christianity in Yorùbá-dominated areas of Nigeria can be traced to the desires and efforts made by the Yorùbá slaves that were granted freedom from England and America after the abolition of slave trade in 1772 (cf. Àyándélé 1966; Peel 1968; Odùyo̩yè 1969; Òshíté̩lú 2002; Jé̩gé̩dé̩ 2008). It will be recalled that in 1772, the Lord Chief Justice of England, Lord Mansfield, gave legal teeth to the abolition of slave trade and as a result of the historical judgment, Freetown and Liberia were founded. The two cities served as training grounds for many of the freed slaves who had come into contact with Christianity during their period of captivity. However, many of the recaptives managed to make their ways inland and to Abé̩òkúta; the present capital of Ògùn State between 1838 and 1842 (cf. Àyándélé 1966: 4–12). The spiritual isolation of the recaptives made them to ask for missionaries, first, to administer to them, and, more importantly, to minister to their heathen brethren who sold them into slavery. In fact, the quest for the establishment of mission stations in many towns and villages in Yorùbá land led to a phenomenal rise in the number of Missionaries of various Denominations coming from Europe and America into some Yorùbá major towns (cf. Odùyo̩yè 1969: 1–22). The result of this was that Lagos, Badagry, Ò̩yó̩, Ìbàdàn, Ìjè̩bú-òde, S̩akí, Ilés̩à, Ifè̩, Oǹdó and Èkìtì land became the strongholds of Christianity by the first decade of the 20th century.

However, the Foreign Missionaries closed their stations and left for their home countries because of the outbreak of epidemic or plague, and the world economic recession as well as the First World War. Christians in Yorùbá land responded to the challenge by establishing prayer groups in order to cater for their spiritual needs. The most popular of such prayer groups was the 'E̩gbé̩ Òkúta Olówóiyebíye' (The Precious Stone Society). The group metamorphosed into the Faith Tabernacle. The Faith Tabernacle later became The Apostolic Faith and the Christ Apostolic Church (cf. Peel, 1968). The crises also resulted in the emergence of an avalanche of 'Aládùúrà' Churches such as the Cherubim and Seraphim Society (C&S) in 1925, the Church of the Lord (Aládù̀úrà) (C.L.A) in 1930 and Celestial Church of Christ (CCC) in 1947. The Aládùúrà Churches are mostly products of the various charismatic movements in Yorùbá land, and the movements started in the second decade of the 20th century (cf. Jé̩gé̩dé̩, 2008).They emerged gradually out of the visionary and prophetic experiences of a considerable number of individuals. Prominent among them were Saint Moses Orímo̩ládé, Primate Josiah Òshíté̩lú, Apostle Joseph Ayò̩ Babalo̩lá and Pastor SBJ Oschoffa, among others.

The 1960s, and 1970s also witnessed the emergence of a new brand of Christianity in Yorùbá land. The era saw the emergence of some Pentecostal and Neo-Pentecostal Churches, prominent among which are the Deeper Life Bible Church, the Redeemed Christian Church of God and Foursquare Gospel Church. This Phenomenon has led to the proliferation of several hundreds of Neo-Pentecostal Churches in Yorùbá-dominated areas of Nigeria. In this paper, we will show that the European or established Churches and the newly founded autochthonous Nigerian Churches have different influences on Yorùbá naming system and tradition-based Yorùbá personal or first names.

One conclusion that can be drawn from previous studies on naming among the Yorùbá people is that naming is an important issue in Yorùbá culture and it is done with fanfare (cf. Dáramó̩lá/Jéjé 1967: 62; Òkédìjí et al. 1971: 68f.; Adéoyè 1972: 5, 1979: 256; E̩kúndayò̩ 1977: 56f.; Akínnàsò 1980: 277f.). Although, there are similarities in the findings of the previous researchers, the researchers do not completely present the same stories about naming among the Yorùbá people. For example, Dáramó̩lá and Jéjé (1967: 62), and Òkédìjí et al. (1971: 68f.) claim that "a male child is named on the 9th day, a female child is named on the 7th day and twins are named on the 8th day". On the other hand, Adéoyè (1972: 5; 1979: 256), E̩kúndayò̩ (1977: 56f.), Akínnàsò (1980: 277f.), and Owólabí et al. (2009: 221) report that many Yorùbá people name their children on the 8th day as a result of Christian and Islamic influences. But, information from two Ifá priests and with what is happening at present on naming among the Yorùbá people show that none of the previous findings can be deemed as completely correct. For example, Ìkò̩tún (2011: 24) reports that "in Yorùbá culture, Ifá is regarded as a repository of the people's culture, history, tradition and values". So, whatever the Ifá priests say is usually regarded as correct and final. The Ifá priests say that naming is done on the sixth day and that is why the Yorùbá people say Ìfàlo̩mo̩ (Every child is a sixth day) although the word 'Ìfàlo̩mo̩' may also mean 'unexpected favour'.

Similarly, some Yorùbá people wrongly pronounce Ìfàlo̩mo̩ as Ifálo̩mo̩ or Fálo̩mo̩ ('A child is Ifá' – the Yorùbá god of wisdom). In fact, there are some Yorùbá people who adopt Fálo̩mo̩ as their names. But, because the Yorùbá Christians do not want to have anything to do with Ifá ('the Yorùbá god of wisdom'), according to them, it is paganism. They change Ìfàlo̩mo̩ (Every child is a sixth day) or Ifálo̩mo̩ (A child is Ifá-the Yorùbá god of wisdom) to È̩bùnlo̩mo̩ (Children are gifts). Therefore, at present, there are five different naming days in the Yorùbá-speaking areas of Nigeria. The Yorùbá traditionalists name their children on the sixth day with fanfare. Members of the European Churches and some Pentecostal Churches name their children on the eighth day with fanfare. Jehovah's Witnesses and members of the Deeper Life Bible Church adopt the day children are born for naming without fanfare and formal religious ceremony. Some Yorùbá Muslims endorse the seventh day while others adopt the eighth day.

Furthermore, Yorùbá Christians who adopt the eighth day cite Luke 2:21 in support of their position. The verse reads:

Now when eight days came to the full for circumcising him, his name was also called Jesus, the name called by the angel before he was conceived in the womb.

But, Jehovah's witnesses argue that the Bible emphasizes the eighth day for circumcision and not naming. Citing Genesis 17:12–14, 21:4; Luke 2:21; John 7:22 and Acts 7:8, they argue further that it is circumcision the Bible discusses and that it is Jewish and not Christian and that there is no verse in the Bible that says Christians should name their children on a particular day. On the other hand, the difference between the Muslim days is traceable to the difference between the Islamic calendar and the Gregorian calendar. The Islamic calendar, like the Jewish calendar, endorses sunset to sunset as a day whereas the Gregorian calendar claims that a day is 12 midnight to 12 midnight. Those who adopt the Islamic calendar endorse the seventh day for naming while those who use the Gregorian calendar name their children on the eighth day.

Akínnàsọ̀ (1980: 279–283) reports that Yorùbá personal names are drawn from the home context (HC) principle that is based on the Yorùbá proverb: Ilé ni à ń wò kí a tó so̩ o̩mo̩ ní orúko̩ ('The condition of the home determines a child's name').

Aḱinnàsọ̀ (1980: 283) also submits that:

Any personal name which invokes unpleasant or negatively valued connotations is obligatorily avoided because the Yorùbá believe (i) that a child's name play some part in its development and future career and consequently (ii) that a child may react to a name having negative social implications.

According to him, the practice of eliminating socially unacceptable information from personal names is based on another Yorùbá proverb: Orúko̩ ní ń ro ni ('A person's name directs his actions and behavior'). The negatively sanctioned home contexts are witchcraft, poverty, disability and criminality. So, only socially valued information in personal names is encouraged and used. Therefore, before the advent of Christianity two rules that guided the choice or construction of Yorùbá personal names as advanced by Akínnàsọ̀ (1980: 279–283) are reproduced below:

Rule 1: A personal name is derived from one or more domestic events that satisfy the home context requirement.

Rule 2: All negatively valued home contexts are raised to positively valued status for the purpose of personal name construction

Rule 1 has the following sub-bases:

1a. the special circumstances that strictly pertain to the birth of the child or its appearance at birth- how was the baby born? E.g. Did it present its legs first rather than the head?

1b. the social, economic, political and other conditions affecting the family or lineage into which the baby was born- was there famine, war, or economic boom?

1c. the (traditional) occupation or profession of the parents or the family line- Are they hunters, drummers, or warriors?

1d. the religious affiliation or deity loyalty of the family- which God or deity is worshipped and what is His/her contribution to the welfare of the family?

However, in this paper we are interested in name change vis-à-vis first names. We will show that rules 1a, 1b and 1c do not serve as bases for constructing personal names among Christians especially members of the newly founded churches any more. This is because, as we shall show later, tradition-based Yorùbá personal/first names are now being replaced by new derivations or names that have Greek scriptural connotations. The deity in rule 1d must also be replaced with the Bible "Lord" if it will serve as a basis for personal name construction among members of the newly founded churches. In addition, the second rule which says "all negatively valued home contexts are raised to positively valued status for the purpose of personal name construction" still holds for members of both established and newly founded churches though this position is at variance with a common Mediterranean principle. According to Akínnàsọ̀ (1980: 283), the common Mediterranean principle avoids "the evil eye and envy by not naming a baby positively in a way to attract envy". Therefore, rule 2 is not a worldwide phenomenon that is applicable to every ethnic group.

In this paper, we are interested in personal or first names. A first name is defined as a name that is given to one when one is born and it must come before one's family name (cf. Turnbull 2010: 560). Ṣówánde and Àjànàkú (1969), Adéoyè (1972), Ẹkúndayọ̀ (1977), Akínnásọ̀ (1980), Babalọlá and Àlàbá (2003) who discuss Yorùbá personal names indicate that tradition-based Yorùbá personal names can be divided into at least eight different categories. The first category shows that there are some Yorùbá names that are called 'àmútọ̀runwá' (names that are brought from heaven). Some of the names in this category are Ìgè (a child who presents the legs first, rather than the head, at birth), Ọ̀kẹ́ (a child born with an unbroken membrane), Òní (literally, Òní means 'today' but culturally, it is a traditional name given to a child who is very small in stature at birth and who ceaselessly cries day and night), Ọ̀la (literally, Ọ̀la means 'tomorrow' but culturally, it is a name given to a child that is born after Òní) and Ọ̀túnla (literally, Ọ̀túnla means 'the day after tomorrow' but culturally, Ọ̀túnla is the younger sibling to Ọ̀la). The second category comprises names that show the people's belief in the deities like Ògún ('The god of iron'), Ọya ('The river goddess'), Ṣàngó (The diety of thunder), Èṣù1 (The law enforcer) and Ifá (The god of wisdom). For example, there are names such as Ògúnyẹmí ('The god of iron fits me'), Ọyáwálé ('The river goddess came home') and Èṣùríyìíkẹ́ ('The law enforcer got this one to treasure').

The third category consists of names that are called orúkọ oyè ('chieftaincy names'), orúkọ ogun ('war names' 2) and ìnagijẹ ('nicknames'). Some of such names are; Apènà ('cult's title'), Balógun ('A generalissimo') and Ajíṣefínní ('A person who will always want to appear neat'). The fourth category includes names that are calledorúkọ àbíkú ('names that are given to those that die and are perceived to have been born again or have staged a comeback'). Examples are: Kásìmáawòó ('Let us continue to watch him') and Kúkọ̀yí ('Death rejected this one'). Names like Ọdúnayọ̀ ('Festival of happiness') and Ọdúnọlá ('Festival of riches') are names that belong to the fifth category and the names are some of the names which show individual social values and expectations. The sixth category shows names that deal with iṣẹ́ ìdílé ('family professions') like Ọdẹ́wálé ('A hunter came home'), and Àgbẹ̀dẹ ('A goldsmith'). The seventh category comprises names that show the people's belief in àsẹ̀yìnwáyé ('reincarnation'). Some examples are; Babájídé ('The father reincarnated'), Ìyábọ̀ ('The mother came back') and Ọdẹ́jídé ('The hunter reincarnated'). The eighth category comprises names that are drawn from oríkì ('eulogy') which are called praise names. A few of the names are: Àbíkẹ́ ('Praise name'/'Born to cherish') and Àkànjí ('Praise name').

But, we are of the opinion that chieftaincy names, nicknames and war names were either titles or appellations which transformed into real names. For example, before the British or Missionary incursions into the southwestern part of Nigeria, each Yorùbá sub-ethnic group had its army. Like ìnagijẹ (nicknames or aliases), an individual who performed well in the war front could either adopt or be named Jagun ('war fighter') or Dágundúró ('war stopper'), to mention a few. As a result of the frequent use of such war names, the names gained popularity over the addressees' real names. Importantly, therefore, such names as these that were mainly titles or appellations, before the advent of Christianity and formal education in Africa, were adopted as fathers' real names by children when the need arose for them to register (e.g. in schools) with their fathers' names. The use of chieftaincy names, nicknames and war names was due to the ignorance of such children who erroneously believed their fathers' appellations and chieftaincy names to be their fathers' real names. In this paper, we will show that new names have been formed by the Yorùbá Christians to replace the tradition-based Yorùbá personal names as first names.

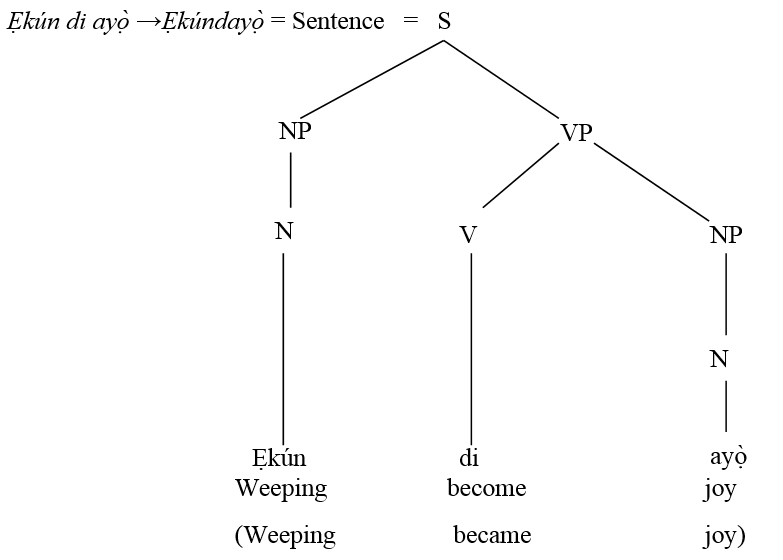

It has been shown that many Yorùbá personal names are sentential names that are the combinations of noun phrases (NPs henceforth) and verb phrases (VPs henceforth) (cf Ẹkúndayọ̀ 1977; Akínnàsọ̀ 1980). For example, Ẹkúndayọ̀ (1977), and Akínnàsọ̀ (1980), discuss Yorùbá Noun Phrases that can be Yorùbá personal names, e.g.

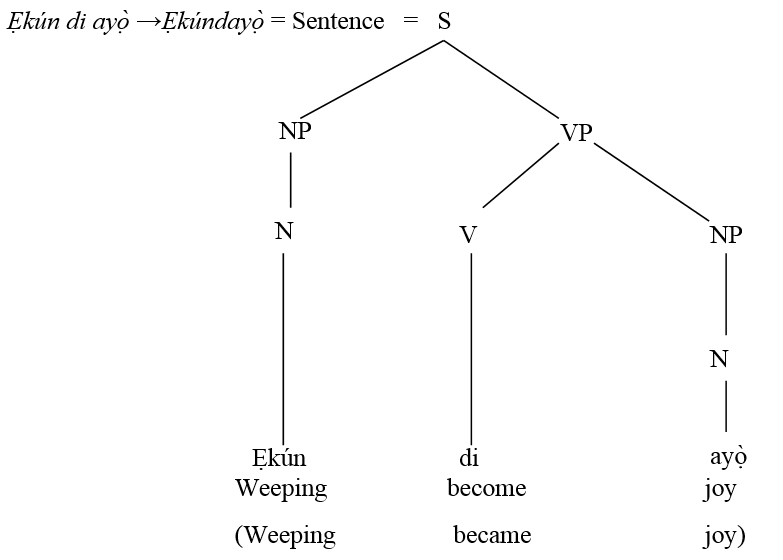

However, in this section, we show that a Yorùbá sentential name can also be a Serial Verb Construction, a Verb Phrase (VP), a Prepositional Phrase (PP), a Focus Construction and a Specifier or a Complementizer, for example Ọdẹ́rìnwálé ('A hunter walked home'). The name is a serial verb construction and can be shown in a tree diagram thus:

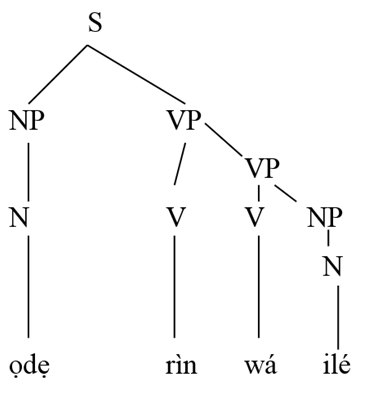

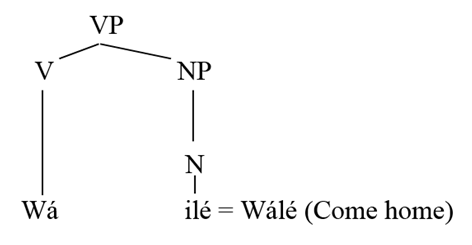

A VP example is: Wálé ('Come home')

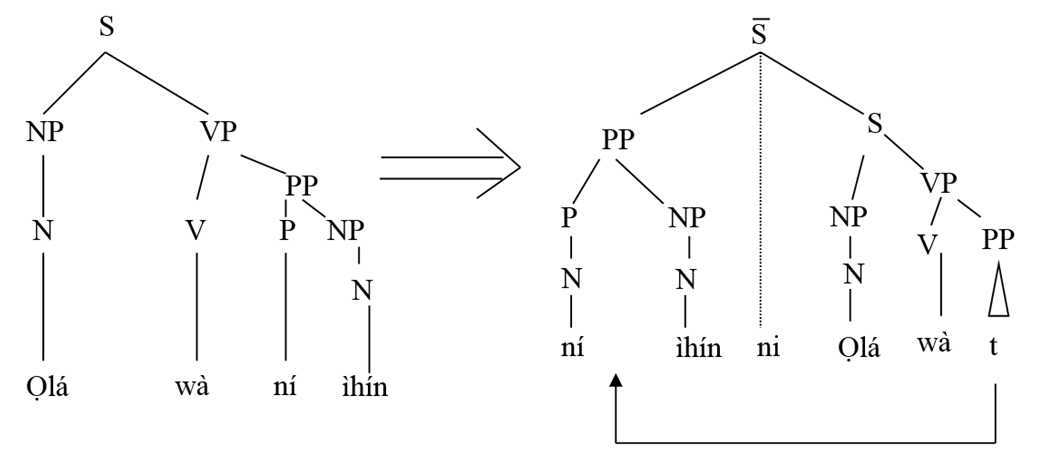

A PP example also is: 'Níhìnínlọláwà' (Riches are here).

Ní ìhín ni ọlá wà = Níhìnínlọláwà ('Riches are here'). This is a sentence derived by a movement from Ọlá wà ní ìhín ('Riches are here').

There are also examples of specifiers. There are some that are drawn from complimentizers and some from inflectional phrases. Some examples are shown below.

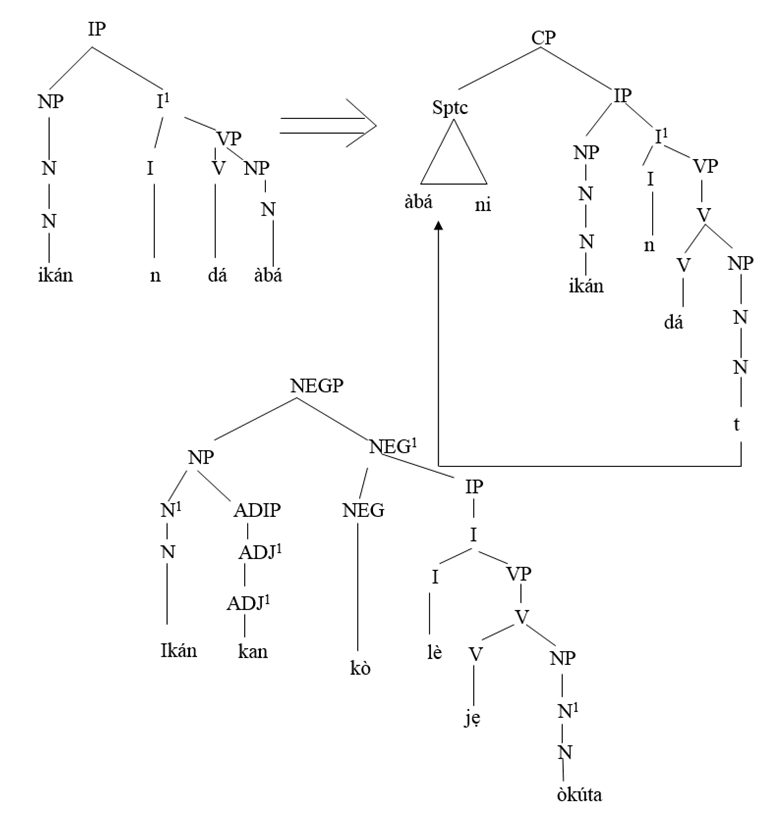

The name 'Àbá ni ikán ń dá' (Termites are only proposing) is the first segment of the sentence Àbá ni ikán ń dá ikán kan ò lè je̩ òkúta ('Termites are only proposing, no termite can eat stone').

The base is Ikán ń dá àbá ('Termites are proposing'). Ikán kan kò le jẹ òkúta ('No termite can eat stone'). We focus the object of the first sentence. Àbá ikán ń dá- Ikán kan kò lè jẹ òkúta ('Termites are only proposing-No termite can eat stone'). We then insert ni: Àbá ni ikán ń dá- Ikán kò lè jẹ òkúta. So, àbá ni ikán ń dá, ikán kan kò lè jẹ òkúta are two sentences. Movement takes place only in the first.

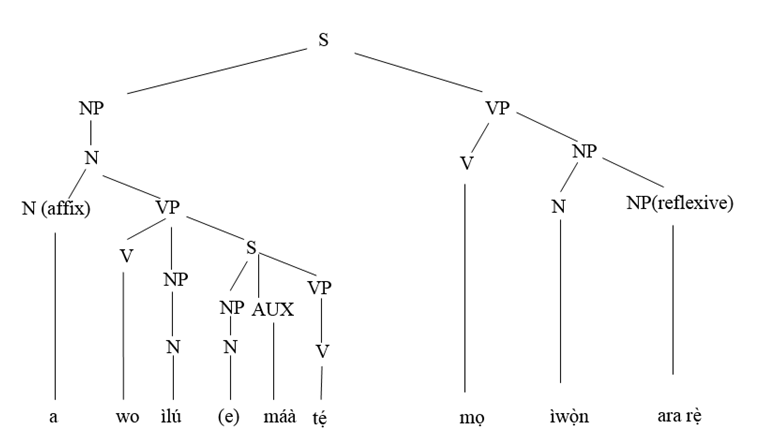

An example of a Yorùbá Personal name which is a focus construction is A wo̩ ìlú má té̩ ('A person who enters a town and is not mocked').

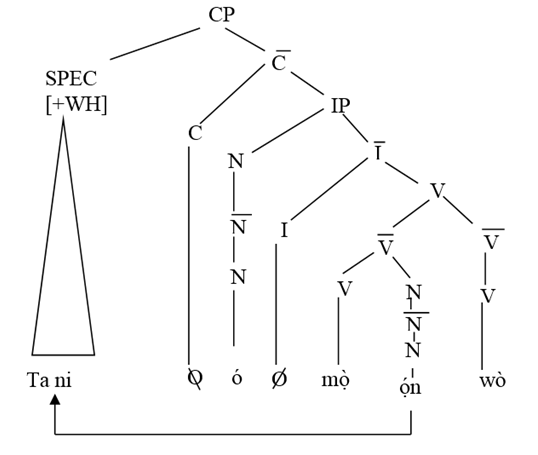

This name is a focus construction derived from Ó mọ ìwọ̀n ara rẹ̀ ('He knows his boundary') by the focusing of the NP object. An example of a Yorùbá Personal name which is a Specifier is also shown below: Tanímọ̀ọ́nwò? ('Who knows how to take care of?').

But, as this discussion progresses we will show that specifiers are no longer adopted as first names because they are alliances or nicknames that were erroneously adopted as parents'names when the need arose to register in schools established by the Missionaries.

Studies conducted on Yorùbá personal names as well as Yorùbá people and published by previous researchers formed part of the data that were used in this work. The researchers are Ṣówándé and Àjànàkú (1969), Odùyọyè (1972), Adéoyè (1972), Ẹkúndayọ̀ (1977), Akínnàsọ̀ (1980) and Ajíbóyè (2009). Other books that were consulted on religions are Olódùmarè God in Yorùbá belief by Ìdòwú (1962), Understanding African Traditional Religion by Káyọ̀dé (1984), The Yorùbá God and gods by Jẹ́miríyè (1998), The Holy Bible: Revised Standard Version,Christianity in West Africa by Kalu (1978), New Dimensions in African Christianity by Gifford (1993) and New Christian Movements in West Africa by Beyer (1998). In addition, Joint Admissions and Matriculation Board's (JAMB) lists of applicants seeking admissions into the Universities of Adó-Èkìtì, Ifẹ̀ and Ìbàdàn were used. In the lists that were sent by the Joint Admissions and Matriculation Board (JAMB), first and surnames or generational names and states of origin of the candidates considered for admission and their dates of birth are clearly shown. The attendance registers of pupils or students of Good Tindings International Schools, Oṣogbo were also considered. Two of the registers are for the Nursery section, three for the Primary section, four for the Junior Secondary and four for the Senior Secondary. The registers equally indicate their bio-data. The lists of staff of the Universities of Adó-Èkìtì, Ifẹ̀ and Ìbàdàn which contain their bio-data were similarly considered. It is believed that the number of students and staff of the three universities is sufficiently representative of all the Yorùbá Christians.

In this section we present names that were drawn from our present study. The names are divided into three groups. The first group consists of names that are formed inYorùbá and are used as first names. They are shown below.

A: First Names

Olúwánífẹ̀ẹ́sími or Nífẹ̀ẹ́sími or Nífẹ̀ẹ́ ('The Lord has love for me')

Tolúwani or Tolúwa or Tolú ('This is the Lord's own')

Ayọ̀mikún or Ayọ̀mi or Ayọ̀ ('My joy is full')

Tèmilolúwa or Tèmilolú or Tèmi ('The Lord is mine')

Tijésùnimí or Tijésù or Nimí ('I am for Jesus')

Jésùtófúnmi or Tófúnmi ('Jesus is enough for me')

Ìfẹ́olúwa or Ìfẹ́olú or Ìfẹ́ ('The Lord's love')

Ooreọ̀fẹ́ or Oore ('The grace')

Mofèyísayọ̀ or Fèyísayọ̀ or Sayọ̀ ('I use this one for joy')

Tèmídayọ̀ or Tèmi or Dayọ̀ ('My own has become joy')

Olúwápamílẹ́rìnínayọ̀ or Pamílẹ́rìnín ('The Lord has made me to laugh')

Iṣẹ́olúwa ('The Lord's work')

Ìyanuolúwa ('The Lord's miracle')

Moyọ̀sore ('I rejoice at gifts')

Moyọ̀sólúwa ('I rejoice on to the Lord')

Olúwapẹ̀lúmi ('The Lord is with me')

Olúwátúnmiṣe ('The Lord has remade me')

Rerelolúwa ('The Lord is good')

Ìràpadà ('Ransom')

Ìtùnú ('Comfort')

Ìtura ('Comfort')

Ìyìn ('Praise')

Iyìolúwa ('The Lord's admiration')

Jésùfẹ́rànmi ('Jesus loves me')

Jésùgbàmí ('Jesus has accepted me')

Jésùńbọ̀ ('Jesus is coming')

Jésùtófúnmi ('Jesus is enough for me')

Kìkìdáọpẹ́ ('All thanks')

Modéolúwa ('I have come oh Lord')

Morólúwayọ̀ ('I see the Lord and rejoice')

Moyinolúwa ('I praise the Lord')

Ògoolúwa ('The Lord's glory')

Olúwádárasími ('The Lord is good to me')

Olúwádùnmínínú ('The Lord has made me to be happy')

Fèyídárà ('Use this to perform wonders')

Fimídárà ('Use me to perform wonders')

Olúwáníífiṣe ('The Lord wants to use this')

Olúwáṣemilóore ('The Lord has favoured me')

Olúwáṣemíyẹ ('The Lord has made me to be fit')

Olúwáṣeunbàbàrà ('The Lord has done something exceedingly great')

Olúwásúnmibáre ('The Lord has made me to see blessings')

Ooreolúwa ('The Lord's grace')

Oore- ọ̀fẹ́ ('Grace')

Oríir ('Fortune')

Oyinolúwa ('The Lord's honey')

Oreolúwa ('The Lord's gift')

Similólúwa ('Rest on the Lord')

Tantólúwa ('Who is like the Lord')

Gígalolúwa ('The Lord is high')

B: Baptismal Names/ First Names

The second category includes Anglicized biblical names used as baptismal names or first names. They are: Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Amos,Solomon, Mathew, Samuel, Reuben, Abraham, Sarah, Priscilla, John 3.

C: European and English Names used as first names

The third group consists of European and English words with Christian connotations. They are as follows: Lewis, Pearse, Margaret, Anthony, Anthonia, Charles, Roseline, Martins Gladys, Vincent, Clare, Praise, Miracle , Salvation, Success, Favour, Goodness, Love, Joy, Hope, Happiness, Wonderful, Faith, Faithful, Rejoice, Marvelous, Godslove, Thank God, It-is-well, Godswill.

As already shown in the introductory section of this paper, we are interested in name change vis-à-vis first names. We have also shown that British or Christian culture is in contact with Yorùbá culture. We want to discuss the negative effect of the British or Christian culture on Yorùbá culture with reference to Yorùbá personal/first names among Yorùbá Christians. Our results will be discussed under two sections namely: Yorùbá personal names and European churches and Yorùbá personal names and newly founded autochthonous Nigerian Churches.

As shown in a previous section of this paper,the Noun Phrases of some Yorùbá personal names, before Christianity was introduced into the Yorùbá-speaking areas of Nigeria in the 1840s, used to be any of the Yorùbá deities or gods. Some examples are again shown below.

Ògúnjẹ́miríyè

'God of Iron make me see salvation'

(The god of iron made me to see salvation)

Èṣùríyìíkẹ́

'Law enforcer see this treasure'

(The law enforcer sees this one to treasure)

Ifábíyìí

'God of divination give birth this'

(The god of divination gave birth to this)

But, when Christianity was embraced, the NP of some Yorùbá sentential names which was that of any of the gods was changed to Olúwa ('Lord') or Ọlọ́run ('God').

Some examples are also as follows:

Olúwájẹ́miríyè

'Lord make me see salvation'

(The Lord made me to see salvation)

Olúwaríyìíkẹ́

'Lord see this treasure'

(The Lord sees this one to treasure)

Olúwábíyìí

'Lord give birth this'

(The Lord gave birth to this)

Furthermore, in addition to the changing of the NPs that has been witnessed in some Yorùbá traditional names, some Yorùbá people, especially those who belong to the age group of forty and above, adopted some Hebrew names with Anglicized forms or spellings that are recorded in the Bible as baptismal names and in some cases as first names. Some examples are:

Hebrew (Anglicized forms): Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Amos, Solomon, Mathew, Samuel, Reuben, Abraham, Sarah, Priscilla4.

Some also adopted European names which include:

Johnson , Lewis, Pearse, Margaret, Anthony, Anthonia, Charles, Roseline, Martins, Gladys, Vincent and Clare.

The European names were wrongly embraced as Christian names.

As already shown in the previous sections of this paper, there are tradition-based Yorùbá personal/first names. The tradition-based names include orúkọ àmútọ̀runwá ('names that are brought from heaven') like ọ̀kẹ́ ('child born inside an unbroken membrane'), orúkọ àbíkú ('names for those that die and are perceived to have been born again'), like Kòkúmọ́ ('He/She will not die again'), names that show people's belief in àṣẹ̀yìnwáyé ('reincarnation') such as Babájídé ('Father has reincarnated') and profession-based names like Àyànwálé ('A drummer came home'). It must be observed also that in the past, the tradition-based names were first names and later, when school system was introduced either first names or parents' names or both. However, in recent years, especially between 1980s and now, the tradition-based Yorùbá personal names no longer exist as first names. The non-use of the tradition-based Yorùbá personal names as first names is due to some reasons that are discussed below.

First, in the past, pregnant women used to give birth to children in most cases at home and, in some cases, on the way to the farm. The people that used to serve as agbẹ̀bí ('mid-wives') or those that assisted the expectant mothers were the parents or grand-parents who knew about the culture of the Yorùbá people. It was those people, after delivery that would announce the child's name because of the circumstances that surrounded the birth of the child. However, between 1980s and now, two major opportunities, namely, improved western medical facilities and church maternity system, are available or within the reach of everybody. So, what pregnant women do is to go to hospitals to be delivered of their babies and the doctors, nurses and midwives who work in the hospitals are the people who do not know the Yorùbá culture or they are trained in the western way. It is also difficult to know babies who are Ìgè (child who presents the legs first rather than the head at birth) or Ọ̀kẹ́ (child born inside an unbroken membrane), to mention a few, because some of the babies are born through caesarian operation. The people that work in the church maternity homes are interested in what Jesus has done, is doing and will do and not what the Yorùbá culture says. Therefore, between 1980s and now, it is difficult to see any Yorùbá person being addressed with any of the orúkọ àmútọ̀runwá (names that are brought from heaven) as a first name.

Similarly, profession-based names like Àyánwálé ('The drummer came home') have almost ceased to exist as first names among the Yorùbá people. This is because the Yorùbá people have abandoned their family-based professions and embraced the opportunities created by Western culture or system. The professions that are now common among the Yorùbá people are professions that are European or Western and they include orthodox medicine, teaching, lecturing, engineering, British-based military service, and piloting. These professions are not native to the Yorùbá people and therefore cannot be NPs of Yorùbá personal names. For example, we do not have Tísàwùmí ('I like Teaching'), and Dókítàsèyí ('The Doctor made this one') just as we have Àyánwálé ('The drummer came home'). This is because there are traditional names for these types of professions i.e. Ifá is akọ́nilọ́rànbíìyèkanẹni ('The born Teacher') while Ọ̀sanyìn is believed to be the medicine man.All things that relate to wars are also designated with Ògún. The factor of exposure or civilization which is made possible by Western education is also responsible for the non-use of the European professions as NPs of Yorùbá personal/sentential names. The awareness is such that no parents could have adopted title names, nicknames and war names as personal names for children at birth. The Yorùbá personal names called orúkọ àbíkú (names for those that die and are perceived to have been born again or have staged a comeback) have almost ceased to be used as first names because, with improved medical facilities that are available, infant mortality has been seriously checked. The messages that are recorded in Ecclesiastes 9:5, 6 and John 5:28, 29 are also responsible for the non-use of orúkọ àbíkú (names for those that die and are perceived to have been born again or have staged a comeback) and names like Babájídé ('The father has reincarnated') which show people's belief in àsẹ̀yìnwáyé ('reincarnation') as first names. The verses read:

For the living are conscious that they will die; but as for the dead, they are conscious of nothing at all, neither do they anymore have wages, because the remembrance of them has been forgotten. Also their love, and their hatred and their envy, is now perished; neither have they any more a portion forever in anything that is done under the sun (Preachers 9:5, 6)

Do not marvel at this, because the hour is coming in which all those in the memorial thumbs will hear his voice and shall come forth, they that have done good, unto the resurrection of life; and they that have done evil, unto the resurrection of damnation (John 5:28, 29)

Therefore, since 1980s, when the new Christian movements began, members of the European churches have been influenced by members of the new Christian movements that anybody who dies can only live again or come back to life during resurrection time as recorded in the book of John 5:28, 29. This, therefore, means that Babajídé ('The father reincarnated') and Yéjídé ('The mother reincarnated') are nothing but lies according to the Bible, since the time of resurrection has not come.

In addition, praise names like Àkànjí, Àyìndé, Àdùkẹ́, and Àdùnní to mention a few are also not adopted as names for children who are below the age 10. There are reasons for the non-use of the praise names. One of the reasons is that mothers and grand-mothers who are below the age 60 do not know the Yorùbá eulogies where the praise names are derived. The few great-grand-parents who know are usually cautioned when they start to recite any of the eulogies such as: Àdùnní, ọmọ ẹkùn, ọmọ erin… ('Àdùnní, the daughter of a leopard, the daughter of an elephant…')5. The reaction from parents would be: Ọmọ̀ mi ò kìí ṣe ọmọ ẹkùn, ọmọ erin, ọmọ Jésù ni ('My daughter is not the daughter of a leopard or an elephant, she is Jesus' daughter').

Furthermore, when Nigerians or Yorùbá people became church founders in the 1980s, new dimensions were introduced into the Yorùbá naming system. The names that have been generated between the 80s and now are in two categories. Any of the people or children who belong to the age group of 11 years and thirty years are addressed with any of the names listed or some others that follow the pattern below:

Olúwánífẹ̀ẹ́sími or Nífẹ̀ẹ́sími or Nífẹ̀ẹ́ ('The Lord has love for me')

Tolúwani or Tolúwa or Tolú ('This is the Lord's own')

Ayọ̀mikún or Ayọ̀mi or Ayò ('My joy is full')

Tèmilolúwa or Tèmilolú or Lolúwa or Tèmi ('The Lord is mine')

Tijésùnimí or Tijésù or Nimí ('I am for Jesus')

Jésùtófúnmi or Tófúnmi ('Jesus is enough for me')

Ìfẹ́olúwa or Ìfẹ́olú or Ìfẹ́ ('The Lord's love')

Ooreọ̀fẹ́ or Oore or Ọ̀fẹ́ ('The grace')

Mofèyísayọ̀ or Fèyísayọ̀ or Sayọ̀ ('I use this one for joy')

Tèmídayọ̀ or Tèmi or Dayọ̀ ('My own has become joy')

Olúwápamílẹ́rìnínayọ̀ or Pamílẹ́rìnín ('The Lord has made me to laugh')

Iṣẹ́olúwa ('The Lord's work')

Ìyanuolúwa ('The Lord's miracle')

Moyọ̀sore ('I rejoice at the Lord's gift')

Moyọ̀sólúwa ('I rejoice on to the Lord')

Olúwapẹ̀lúmi ('The Lord is with me')

Olúwátúnmiṣe ('The Lord has remade me')

Similarly, there are instances of some Yorùbá people who belong to the age group of 10 years and below and any of these children is addressed with any of the names listed below. However, the names that are shown below are in two categories. While the first category shows names that are formed in Yorùbá, the second category comprises English words that are adopted as names. The English words have Christian connotations and they are drawn from Greek scriptures which some Christians call New Testament. The names are:

Rerelolúwa ('The Lord is good')

Ìràpadà ('Ransom')

Ìtùnú ('Comfort')

Ìtura ('Comfort')

Ìyìn ('Praise')

Iyìolúwa ('The Lord's admiration')

Jésùfẹ́rànmi ('Jesus loves me')

Jésùgbàmí ('Jesus has accepted me')

Jésùńbọ̀ ('Jesus is coming')

Jésùtófúnmi ('Jesus is enough for me')

Kìkìdáọpẹ́ ('All thanks')

Modéolúwa ('I have come oh Lord')

Morólúwayọ̀ ('I have seen the Lord to rejoice')

Moyinolúwa ('I praise the Lord')

Ògoolúwa ('The Lord's glory')

Olúwádárasími ('The Lord is good to me')

Olúwádùnmínínú ('The Lord has made me to be happy')

Fèyídárà ('Use this to perform wonders')

Fimídárà ('Use me to perform wonders')

Olúwáníífiṣe ('The Lord wants to use this')

Olúwáṣemilóore ('The Lord has favoured me')

Olúwáṣemíyẹ ('The Lord has made me to be fit')

Olúwáṣeunbàbàrà ('The Lord has performed exceedingly great')

Olúwásúnmibáre ('The Lord has made me to see blessings')

Ooreolúwa ('The Lord's grace')

Oore-ọ̀fẹ́ ('Grace')

Oríire ('Fortune')

Oyinolúwa ('The Lord's honey')

Ooreolúwa ('The Lord's gift')

Similólúwa ('Rest on the Lord')

Tantólúwa ('Who is like the Lord')

Gígalolúwa ('The Lord is high')

As earlier mentioned, some also adopt English words with Christian connotations, and, in some cases, sentences, as names for their children. The English words are: Praise, Miracle, Salvation, Success, Godslove, Godswill, Love, Joy, Hope, Happiness, Wonderful, Faith, Faithful, Rejoice, Favour, Goodness, Marvelous.

The English sentences are 'Thank God', and 'It-is-well' (It is well). However, to show that the newly established Nigerian churches understand the Bible teachings better than the European churches, members had to introduce what they called emotion-packed-salvation activities that would show a drastic departure from the past especially the method established by the European churches. The activities are therefore shrouded in fanaticism, flavours, modernisation and especially names that endear the Nigerian believers to one another.

In this paper, we examined Yorùbá personal/first names before and during the advent of Christianity in Yorùbá-speaking areas of Nigeria. We showed that before the advent of Christianity previous studies on Yorùbá personal names indicated that the names were drawn from home context (HC). The home context included special circumstances surrounding the births of children, the social, economic, political and other conditions of parents or families, the occupation or profession of the parents and the religious affiliation or deity loyalty of the family.

However, in our present study, we showed that when the European-led Christianity was embraced by a number of Yorùbá people, new dimensions were introduced into the Yorùbá naming systems. The new dimensions included the modifications of Yorùbá personal names whereby the NPs, which showed belief in Yorùbá gods, were replaced, in most cases, with the word Olúwa ('Lord') or, in some cases, O̩ló̩run ('God'). The new dimensions also included the introduction of Hebrew and European names into the Yorùbá naming system and such names were called baptismal names.

We also argued that when Nigerian-led Christian movements or churches came on board between 1960s and 1980s, some other dimensions were again introduced into the Yorùbá naming systems. The other dimensions include non-use of tradition-based Yorùbá personal names as first names and the formation or derivations of new names in Yorùbá and English and the new names have Christian connotations and they are drawn from Greek scriptures which some Christians call the New Testament. We further argued that the newly founded Nigerian churches introduce activities that are shrouded in fanaticism, flavours and names that endear the members to one another to show that they understand the bible teachings better than the European churches and that the findings of this study show that name modification or name change is inevitable when there is acculturation.

Adéoyè, Christopher L. (1972): Orúkọ Yorùbá. Ìbàdàn: Ìbàdàn University Press.

Adéoyè, Christopher L. (1979): Às̩à àti Ìs̩e Yorùbá. Ìbàdàn: Ìbàdàn University Press.

Ajíbóyè, Ọládiípọ̀ (2009): New Trends in Yorùbá Personal Names: Sociological, Religious and Linguistic Implications. Lagos, Manuscript: 1–8.

Akínnásò, Funṣọ N. (1980): "The Sociolinguistic Basis of Yorùbá Personal Names". Anthropological Linguistics 22/7: 275–304.

Àyándélé, Emmanuel A. (1966): The Missionary Impact on Modern Nigeria (1842–1914). London: Longman Group Limited.

Babalọlá, Adébóyè/Àlàbá, Olúgbóyèga (2003): A Dictionary of Yorùbá Personal Names. Lagos: West African Publishers.

Beyer, Engelbert (1998): New Christian Movements in West Africa. Ìbàdàn: Sefer.

Dáramó̩lá, Olú/Jéjé, Adébáyọ̀ (1967): Àwo̩n Àṣà àti Òrìṣà Ilè̩ Yorùbá. Ìbàdàn: Oníbo̩n-Òjé Press/Book Industries.

Ẹkúndayọ̀, Samuel A. (1977) "Restrictions on Personal Name sentences in the Yorùbá Noun Phrase". African Linguistics 19: 55–77

Gifford, Paul (ed.) (1993): New Dimensions in African Christianity. Ìbàdàn: Sefer.

Ìdòwú, Bọ́lájí E. (1962): Olódùmarè: God in Yorùbá Belief. Ikeja: Longman.

Ìkọ̀tún, Reuben O. (2011): "The Sociolinguistic Criteria Guiding Invitation To Meals Among The Yorùbá of South-Western Nigeria ". Journal of West African Languages 38/2: 21–31.

Jé̩gé̩dé̩, Gbénga G. (2008): The History of the Aládùúrà Churches in Èkìtì land, 1925–2005. PhD-Thesis, University of Ado-Ekiti, Nigeria.

Jẹ́miríyè, Timothy F. (1998): The Yorùbá God and gods. Adó-Èkìtì: PETOA.

Kalu Ogbu (ed.) (1978): Christianity in West Africa: The Nigerian Story. Ìbàdàn: Daystar Press.

Káyọ̀dé, John O. (1984): Understanding African Traditional Religion. Ilé-Ifẹ̀: University of Ife Press.

Odùyo̩yè, Modúpẹ́ (1969): Planting of Christianity in Yorùbá-land, (1842–1888). Ìbàdàn: Day Star Press.

Odùyo̩yè, Modúpẹ́ (1972): Yorùbá Names: Their Structure and Their Meanings. Ìbàdàn: Daystay Press.

Òkédìjí, Olú F. et al. (1971): "The Sociological Aspects of Traditional Yorùbá Names and Titles". Odù 5: 64–79.

O̩ládìjà, Olú J. (1980): "African Response to Christianity: The Yorùbá Episode". In: NASR Conference Papers. Proceedings of the Nigerian Association for the Study of Religions held at the University of Jos, Jos, 1st–6th September, 1980, no 2: 80.

Òshíté̩lú, Gideon A. (2002): Expansion of Christianity in West Africa. Ìbàdàn: Oputoru Books.

O̩shìn, Christopher O. (1983): "Pentecostal Perspectives of the Christ Apostolic Church". Ìbàdàn Journal of Religious Studies XVI/2: 23.

Owólabí, Olú et al. (2009): Ìwé Ìgbàradì Fún Ìdánwò Às̩ekágbá Yorùbá Ilé E̩kó̩ Ṣé̩kó̩ndírì Àgbà. Ìbàdàn: Evans Brothers.

Oyètádé, Solomon O. (1995): "A Sociolinguistic Analysis of Address Forms in Yorùbá". Language in Society 24/4: 515–535.

Peel, John D. Y. (1968): Aládùúrà: A Religious Movement among the Yorùbá. New York: O.U.P.

Ṣówándé, Fẹlá/Àjànàkú, Fágbèmí (1969): Orúkọ Àmútọ̀runwá. Ìbàdàn: Ìbàdàn University Press.

The Holy Bible . London: Cambridge University Press.

Turnbull, Joanna (2010): Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary of Current English. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Vidal, Túnjí (1986): "The Westernization of African Music: A Study of Yorùbá Liturgical Church Music". Annals of the Institute of Cultural Studies University of Ife: 70–82.

Yémitàn, Ọládiípọ̀/Ògúndélé, Ọlájídé (1970): Ojú Òṣùpá Apá Kejì. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

1 Èṣù ('The law enforcer') in Yorùbá traditional religion is different from Èṣù ('satan') in Christianity and Islam. Èṣù ('The law enforcer'), according to Jẹ́miríyè (1998: 48) (a professor of traditional religion), is one of the Yorùbá gods that has its followers or worshippers. This is the reason why some of its worshippers adopt names like Èṣùbíyìí ('The law enforcer gave birth to this one'), Èṣùríyíkẹ́ ('The law enforcer got this one to treasure'). back

2 There are four categories of war names among the Yorùbá people. The first category comprises names that have the word ogun ('war'). Some examples are: A bí de ogun → Abídogun ('Born before a war time'), Bá ogun dé → Bógundé ('Born during a war time'). The addressees were named as such because they were born during war times. The second category also has ogun ('war'). They are: Dá ogun dúró → Dágundúró ('A war stopper'), A rí ogun yọ̀ → Arógunyọ̀ ('A person who is happy at seeing wars'). The third category has the word ìjà ('fight'), .e.g Àjàkáyé ('A person that fights round the world'). Names in the second and third categories are ìnagije̩ ('nicknames'). The fourth category includes names that do not have ogun ('war') but, in the past, the users of the names were war lords and they were very popular. Such names include: Ògúnmọ́lá of the Ìbàdàn army, Ògèdèǹgbé of the Ìjẹ̀ṣà army and, later, of the Èkìtì Parapọ̀ army and Fábùnmi of the Èkìtì Parapọ̀ army. Names in the fourth category, like the first category, are real names given at birth. back

3 John is an English name which stems from the Hebrew name Johanan (Jo.ha′nan). back

4 Priscilla was a Jew and her husband was Aquila. Both helped Apostle Paul in his missionary work at Corinth. Aquila, Priscilla and Paul were tent-makers (see Acts 18: 1–3). back

5 That a child is called the child of a leopard or an elephant does not make the child to be a child of a beast, rather, the child is only being described as being very powerful and strong because the two animals are very strong and powerful. back