This article deals with the potential influence of the information structure in a given type of discourse on the acquisition of linguistic means. According to previous studies within the functionalist approach1, the linguistic resources mobilized by speakers depend on the discourse context of production (cf. Dimroth/Starren 2003). Other studies on L2 acquisition describe this process as the result of communicative logic: adult learners elaborate linguistic structures according to their communicative needs (cf. Perdue 1993b).

This is the type of question addressed here, as we look at the acquisition of the noun phrase (NP) in L2 French 2. The aim of our study is to show that the acquisitional path of noun determination is partially different, at least depending on the communicative task the learner has to deal with.

Previous studies on NP acquisition in L2 French presented in section 1.4 suggest that the definite value of the French determiner appears earlier compared to the indefinite value expressed by the indefinite article. However, these works did not compare systematically the learners’ use of NPs in different types of discourse and mainly focused on narratives and conversations.

Thus, our hypothesis is that the order of acquisition of the determination system in French has to be considered in the context of discourse production.

To test this hypothesis, we analyze the use of NPs to refer to entities (objects and/or protagonists in L2 French in two types of discourse (film retelling and spatial description) produced by Polish learners of French in three levels of proficiency.

It is important to notice that previous work on L2 acquisition assigns an important role to the characteristics of both the source language (SL) and target language (TL). In our study, we shall focus especially on the properties of the target language, French, which structures NP acquisition. This language is characterized by the obligatory use of a pre-nominal determiner with various grammatical markers such as gender and number. Although this constraint is not absolute, as the omission of a determiner is acceptable or necessary in certain contexts, French appears as a particularly restrictive language in this field, compared to other Romance languages and to Germanic languages with obligatory determiners. Consequently, French as a target language is interesting if we want to examine the interaction between linguistic constraints and the organization of information in various types of discourse during L2 acquisition.

The learners' source language, Polish, contrasts with French with respect to the determination system, as it is one of the so-called "languages without articles". Indeed, there is no obligatory grammatical article, although optional determiners are used. Since we only consider the productions of Polish learners, we cannot estimate more accurately the impact of L1 on the productions in L2. In order to cover the potential influence of Polish on the learners' French discourse, we refer to works on the productions of learners with other source languages in the discussion of our results in section 4.3.

This article is organized in four sections. Section 1 presents our theoretical perspective and previous works on the two types of discourse structure considered in our study, spatial description (Section 1.2) and film retelling (Section 1.3), as well as on the acquisition of the NP in L2 French (Section 1.4). The presentation of the analyzed data (Section 2) is followed by the description of the results (Section 3), which are then synthesized and discussed in section 4.

The construction of a complex discourse requires from the speaker to control both the characteristic patterns of a specific type of discourse and the linguistic means used to convey information about various referential domains. The interaction between the discourse level and the sentence level raises acquisitional problems even for advanced learners. In fact, this interaction is different from one language to another (e.g. Carroll/von Stutterheim 1993; Lambert et al. 2008) and can vary according to types of discourse within a single language (Hendriks et al. 2004).

For our purposes, information structure is defined as the organization of information to be expressed in a discourse according to the communicative purpose imposed by the context of discourse. This includes coherence and connectivity between utterances and the marking of information status (introduction of referents, change of reference, maintained and resumed reference) relative to various referential domains such as time, space, events, entities or modality. These domains are more or less involved and put in the foreground according to the type of discourse. This way of considering information structure matches the model of discourse analysis proposed by Klein and von Stutterheim (1991). This model, called the quaestio model, has been widely used in a series of works on language acquisition (cf. Section 1.2) and allows the identification of the characteristics of various types of discourse, narrative and spatial description in particular. According to this model, any coherent discourse answers a global question, implicit or explicit, called the quaestio, which must then be reconstructed from the speakers' performances in response to the same instruction in a given task.

While producing a coherent discourse, the speaker has to organize the information to be transmitted in the mentioned referential domains. Depending on the quaestio, some referential domains are more implied than others, according to the type of given discourse. The information about these referential domains develops from one utterance to another, and corresponds to the referential movement – the introduction and continuation (maintenance, change or resumption) of reference in the discourse. The marking of referential moves is realized through linguistic cohesive means such as connectors, anaphora or word order.

As for reference to entities, we use the term of introduction of entities with respect to extralinguistic referents, i.e. the objects and protagonists represented in the poster described and the protagonists of the retold movie. The introduction of entities corresponds to the first mention of an entity in the discourse. Once an entity has been introduced, it can be referred to as such in a sequence of utterances – to which we refer as the maintained reference. The speaker can also decide to refer to another entity, which has not been mentioned yet in the discourse. This type of referential movement is termed change of reference. During production, the speaker sometimes decides to reintroduce an entity referred to earlier, in a more distant subsection—a move termed resumed reference.

In the sections below, we illustrate, using previous works, how these various types of referential movement are marked in descriptions and narratives in Polish and in French (cf. Sections 1.2 and 1.3), and what is the acquisitional path of NPs in L2 French (cf. Section 1.4).

A static spatial description is a type of discourse obtained through a communicative task involving the description of a poster depicting an image of a city3 (cf. Carroll/von Stutterheim 1993); the task instruction is: "describe this poster to somebody who does not see it and who will have to draw it by listening to your description". This task requires the expression in discourse of a static locative relation between an entity used as a reference point (relatum) and an entity to be located (theme)4.

Numerous works (cf. Carroll/von Stutterheim 1993; Carroll et al. 2000; Watorek 1998, 2003; Hendriks/Watorek 2008) analyzed the spatial description resulting from this task as a discourse answering the global quaestio "Where is what in L?". L corresponds to the total space to be described (the poster) where various entities (objects and protagonists) are located with respect to one another. This global quaestio determines the central referential domains in the description, namely space and entities. During the production of a descriptive discourse, the speaker updates either the information regarding the space bounded by a relatum, or the information regarding the theme. Foreground utterances express a static spatial location, produced by answering two variants of the quaestio: "What is there in Ln+1?" (used in most cases) and "Where is such x?" (more limited use) (cf. Hendriks/Watorek 2008). Background utterances answer other questions and provide information about the actions of the entities represented on the poster ("what is such x doing?") or about their properties ("how is he/she?").

The distinction between theme and relatum is crucial in descriptions and must be taken into account in the analysis of the linguistic means, which express them. The introduction of relata can be left implicit, as relatum is the discourse topic given in the global quaestio. On the other hand, the introduction of themes must always be marked. In continuation movement, the information on relata is regularly maintained throughout the discourse. The information regarding themes is systematically changed. On the other hand, a change of reference to relata is less frequent. It takes place in topic position, when the speaker wants to mark a referential break in both domains, for both entities and space. This case of change corresponds to a resumption of reference, as the speaker refers to one of the sub-spaces of the global relatum (the poster), which is a part of the context (cf. Section 1.3, resumed reference to protagonists in narratives).

Watorek (2003), Watorek/Dimroth (2005) and Hendriks/Watorek (2008) compared the descriptions produced in French and Polish. In French, the NP referring to a relatum is a definite NP (le+N) or a demonstrative NP (ce+N). It is either information given in the context, or maintained with respect to the co-text. That is why even the introduction of reference to relata can be encoded by NPs with a definite value. On the other hand, themes are mainly expressed by indefinite NPs (un+N), in the case of introduction or change of reference.

(1)

a. au milieu de l’affiche (Rel) il y a une grande place (Th)

<in the middle of the poster there is a big square>

b. sur cette place (Rel) on voit des arbres (Th) un tabac (Th) et une fontaine (Th)

<on this square we can see trees a tobacconist and a fountain>

c. à côté de la fontaine (Rel) il y a un monsieur (Th)

<next to the fountain there is a gentleman>

d. qui (Th) se trouve plus à gauche.

<who is standing more on the left>.

In this example5, the relatum (the poster) is introduced as topic in the first utterance (a) with a definite NP; this information is given in the quaestio as the total space to be described (L). The first theme to be located, "a square", is also introduced in the first utterance (a), in focus, with an indefinite NP. In (b), the information relative to the relatum is maintained in topic by a NP with a definite value (ce+N) and serves as a point of reference to the location of a series of themes, expressed in focus with indefinite NPs (trees, tobacco, fountain). One of these themes is maintained as a relatum in the topic of the following utterance (c), with a definite NP, allowing the location of a new theme (a gentleman) as focus with an indefinite NP, marking the change of reference, as in (b). Utterance (d) answers the second variant of the quaestio, where the theme is maintained as topic by the relative pronoun "which" and located again in relation to the global space of the poster according to the speaker's position. The maintenance of information to themes, which is rarely expressed in the learners' data, is frequent in the production of French native speakers. In contrast, it is sporadic in the production of Polish native speakers, as indicated in Hendriks/Watorek (2008).

In Polish, the introduction of relata, as well as the introduction and the change of reference to themes, is usually encoded by a bare noun (N) or, less frequently, by a NP with an optional determiner, the numeral jeden ('one') and the adjective jakis ('certain'). Maintained reference to themes and relata, and the introduction of relata, information given in the context, are also marked by bare nouns (N) or nouns with a demonstrative (ten+N). The example below, from APN database6 analysed in Hendriks/Watorek (2008) 7, shows these uses.

(2) 8

a. z tylu placu (Rel) ciagna sie kamienice (Th)

behind square-Gen lay buildings-Nom

<behind the square there are buildings>

b. na srodku placu (Rel) stoi fontanna (Th)

at the middle square-Gen is standing fountain-Nom

<in the middle of the square there is a fountain>

c. obok tej fontanny (Rel) czyta gazete jakis pan (Th)

side this-Gen fountain-Gen reads journal certain gentleman-Nom

<beside the fountain there is a man reading a newspaper>

The introduction of the relatum in topic, and the theme in the focus of the utterance (a), is expressed by bare nouns (placu=square, kamienice=buildings). The information about the theme introduced in the focus of (a) is maintained as the information about the relatum in the topic of (b), using a bare noun (placu=square). The shift of information relative to the theme in the focus of (b) is also encoded by a bare noun ( fontanna=fountain). The maintenance of this information in the topic of (c) is realized by a demonstrative NP (tej fontanny=this fountain). The change of reference in the domain of themes is encoded by a noun with the adjective "jakis" ('certain'), an optional determiner which expresses an indefinite value.

Watorek (2003) compares the use of NPs with a definite value, 'le+N' / 'ce+N' in French with the use of 'N' / 'ten+N' in Polish to maintain reference to entities in descriptions. She notes that French native speakers clearly prefer the use of the definite NP (le+N) for the immediate maintenance of reference when an entity is maintained from one utterance to the next. On the other hand, the demonstrative is used for the marking of resumed reference when an entity has been referred to in a distant co-text in the discourse (81.5% of demonstrative NPs are used for resumed reference). In Polish, the percentage of use of the demonstrative (ten+N) is higher than in French for the marking of immediate maintenance of reference (39.8% of demonstrative NPs mark immediate maintenance in Polish, 18.5% in French).

In French, the definite NP (le+N) generally marks immediate maintenance of reference to entities, while the demonstrative is considered more marked and used to resume reference, whereas in Polish, which lacks obligatory determiners, bare nouns and demonstratives constitute more or less equivalent means for the marking of maintenance.

Fictional narratives have been elicited by a task of film retelling, which consists of telling the plot of a 4 minutes cartoon, "Reksio" 9, to an interlocutor who has not seen the film. The speaker responds to the following instruction: "You have just looked at a film that I don't know. Can you tell me the story?". The cartoon presents two protagonists, a dog and a boy, who are going skating on a frozen lake. The ice breaks and the boy falls into the water. His dog finally saves him. It is a classic narrative task where the speaker has to express a series of events involving the protagonists, by taking into account the absence of shared knowledge with the interlocutor 10. This stimulus was used for the first time in the project "Construction du discours par des apprenants de langues, enfants et adultes" (cf. APN, Watorek project 2004) and has led to numerous studies on narrative discourse in Polish and/or French (cf. Lenart 2006; Lenart/Perdue 2004; Lambert/Lenart 2004; Benazzo 2004; Hendriks et al. 2004).

This type of narrative can be considered as an answer to the global quaestio "what happened in Ti?" where Ti corresponds to the global referential time interval covering the whole duration of the story. The quaestio determines the central referential domains of the narrative: time, events and entities, the protagonists. The foreground of a narrative discourse is composed of utterances referring to events which are chronologically situated with respect to an ordered sub-interval, answering two variants of the quaestio: "what happens in Ti+1 for P?" (which is the most frequent) and "what happens in Ti+1?". This constitutes the skeleton of discourse (cf. Labov 1978), which can be enriched by utterances answering secondary questions (such as who, why, where, how). These utterances establish the background11 of the narrative (e.g. descriptions, evaluations, comments).

In accordance with the referential movement in the domain of entities, the protagonists must necessarily be introduced in the narrative. Given the stimulus of the task, in which two characters (a dog and a boy) are involved in the story, the speakers can build sequences where either one or the other protagonist is maintained through several utterances. Change of reference between the protagonists is local, but on the global level of discourse, this involves resumed reference to one of the protagonists. This takes place when one of the two protagonists is reintroduced into the discourse after the other has been referred to in more than two successive utterances.

The works mentioned above show that French native speakers encode the information to the protagonists by an indefinite NP to introduce the referents ( un chien 'a dog', un garçon 'a boy'), but encode maintenance using a definite NP (le chien 'the dog'), a possessive or a demonstrative NP, or a personal pronoun (il). Various types of NPs with a definite value (nouns with a definite article, a possessive or a demonstrative) can mark resumed reference. Let us note that the possessive establishes a semantic link between the protagonists ( le chien et son maître 'the dog and his master'). The demonstrative is rare and is essentially used to reintroduce an entity that was absent in the sequence. The introduction of information relative to the protagonists is typically realized in French by a presentative structure ( c'est l'histoire de/c'est/il y a12 'this is the story of/it's/there is') in a background utterance. The example below illustrates the referential movement in an extract of narrative produced by a French native speaker.

(3)

a. c’est l’histoire d’un chien (P1) et d’un garçon (P2)13 Background

<this is the story of a dog and a boy>

b. c’est l’hiver B

<it is the winter>

c. (T)14 le chien (P1) sort de sa niche Foreground

<the dog gets out of his kennel>

d. ensuite (T) il (P1) sonne chez son maître (P2) F

<afterwards he rings at his master's>

e. et puis (T) le garçon (P2) sort F

<and then the boy gets out>

The narrative begins with two utterances of the background (a and b), introducing both protagonists (dog and boy) in (a) and the setting of the story in (b). One of the protagonists (the dog) is maintained as topic in two successive utterances of the foreground (c and d) and the reference to the second protagonist is resumed with a possessive NP in focus. Then, the information relative to the boy is maintained in the topic of (e).

The works on Polish show that the introduction of entities is systematically encoded in the foreground with a lexical verb referring to the first event of the story, by means of a bare noun (subject) in a post-verbal position and constituting the expression of focus. However, other utterance patterns are possible. The noun is very rarely accompanied by the indefinite jakis ('someone')... This optional local marking is more often attested in structures where the noun encoding introduction is a preposed subject. The marking of maintained reference to the protagonists is realized through zero anaphora (Polish is a pro-drop language) or using a bare noun. We also show the use of optional determiners with a definite value, such as the possessive and more rarely the demonstrative, as found in the productions in French. Bare nouns and changes in word order thus generally mark the information status in the domain of entities.

Example 4 illustrates this marking in a native Polish narrative. The information relative to one of the protagonists (the dog) is introduced in focus (a) with a bare noun in post-verbal subject position. Reference to the same protagonist is maintained in the topic of the following utterance by zero anaphora and the second protagonist is introduced in focus with a possessive NP in object position (b). The information relative to the master is then maintained with another bare noun in post-verbal subject position (c) and using the zero anaphora (d).

(4)

a. (T) rano budzi sie pies (P1) F

morning wakes up dog

<in the morning the dog wakes up>

b. (T) ø (P1) idzie zapukac do domu swojego pana (P2) F

ø goes to knock at house of his master

<(he) goes to knock at his master's house>

c. (T) wyszedl chlopiec (P2) F

came out boy

<the boy came out>

d. (T) i ø (P2) przywital pieska (P1) F

and ø greeted dog

<and (he) greeted the dog>

In summary, French and Polish provide different means of marking the status of referential information to entities. The absence of articles in Polish is a major difference to French, and constitutes a true challenge for Polish speakers learning French, as they have to learn to employ a new grammatical category and its discourse significance. The word order in French does not contribute much to the marking of the status of information, contrary to Polish, where the changing order of the constituents plays a major role (cf. Aleksandrova 2012, for Russian).

The acquisition of NP structure to mark reference to entities in L2 French has been studied in a number of works whose results have been synthesized into a collective book (Véronique (ed.) et al. 2009). The authors follow studies that examine the initial acquisition of French in a functionalist (ESF program, cf. Perdue 1993a) and a generativist framework (URS program, cf. Granfeldt 2003), and examining advanced learners of various levels (program 'Structure des lectes d'apprenants', cf. Hendriks 2005). The acquisitional path of NP structure implies speakers with various source languages: Spanish and Arabic (cf. Perdue 1993a), Swedish (cf. Granfeldt 2003), English (cf. Prodeau 1998; Carroll 1989, 1999), Dutch and Japanese (cf. Sleeman 2004), Korean (cf. Kim et al. 2006), Chinese (cf. Hendriks 2000). Participants were faced with a variety of tasks including free conversations, personal or fictional narratives, descriptions of images, and assembly instructions.

The study of the acquisitional paths for nouns and pronouns in French indicates some influence of the learners' SL on the shape of the developmental sequences. In spite of the difficulty to precisely establish the morphosyntactic development at the nominal level, the authors show the major trends revealed in the study of primarily oral data.

According to this path, learners begin by acquiring the definite article, which is very salient in French, but using a unique form that does not vary with gender or number, and employ this form to express information known in the context. This form is first opposed to an absence of marking (bare noun), then diversifies and marks the number, at first by means of numeral adjectives or the expression of quantity beaucoup de ('a lot of'). The singular/plural distinction is the first to be acquired (cf. Perdue 1993a). Male/female contrast is mastered much later, when gender is morphologically marked (cf. Carroll 1999); masculine forms are mostly used by default (cf. Bartning 2000; Dewaele/Véronique 2000; Prodeau/Carlo 2002)

In the first productions of the indefinite NP, which develops after the definite NP, un has a value of a quantifier and thus plays the same role as the other numeral determiners. This form gets an indefinite meaning by gradual diversification, in the feminine then in the plural. As a general rule, learners first acquire the prototypical uses of a form: the definite article for specificity, the singular indefinite article for singularity (representation of a single entity). The demonstrative, formally more complex, is acquired later than the article. It is used with the definite article to mark the anaphoric resumption of reference. Some learners tend to overuse the demonstrative and even the possessive, in contexts where French native speakers use the definite article (cf. Sleeman 2004). Granfeldt (2000) notes that the demonstrative appears earlier in learners' productions in a guided environment.

Beyond the basic variety level, as identified by Klein/Perdue (1997), acquisitional paths of noun determination vary, as they are more liable to be influenced by source languages and the type of exposure to TL. At this more advanced level of acquisition, the learners (whose productions have been analysed for example by Hendriks 2000, Kim et al. 2006) interpret the data they are exposed to in order to formulate hypotheses that are in coherence with their L1. In a study on narratives in L3 French (Trévisiol 2003) involving Japanese learners’ and native speakers’ data an idiosyncratic use of articles has been attested, compatible with the speakers' preferences in L1 in this type of discourse: the indefinite NP un(e) used to maintain or reintroduce a referent in a type of utterance where the protagonist was not presupposed, answering the quaestio: "and then, what's going on?" (2nd variant of the quaestio), just like native speakers did when they used "non topicalised sentences" 15 with the particle ga.

In another study concerning the construction of anaphoric links in spatial descriptions produced by intermediate and advanced Polish learners of French, Watorek (2003) shows that these learners use more demonstratives in contexts of immediate maintenance of reference whereas French native speakers prefer to employ the NP with a definite article and reserve the demonstrative NP to mark reintroduction (cf. Section 1.2). This result suggests that intermediate and advanced learners, who are aware of the existence of an obligatory determiner in French, seek linguistic means in the TL that are equivalent to the available forms in their SL. Indeed, as we saw in the previous section, this is the case with the demonstrative and the possessive forms for Polish speakers, as these constitute a class of optional determiners with a definite value in SL Polish.

Similar results were obtained in a study on the acquisition of nominal determination in narratives in French, produced by beginner and advanced Polish learners (Lenart 2006). These learners, from the beginner level, use the demonstrative in maintenance contexts, whereas French native speakers appeal to other means.

Previous studies on narratives and spatial descriptions in French and in Polish presented above show interesting differences in the interaction between information and linguistic structures. The impact of these types of discourse on the acquisition of NPs in L2 French is analyzed here in data sets containing both types of discourse produced by the same speakers. Thus, we base our study on the productions of Polish speakers learning L2 French in three levels of proficiency (beginners – group I, intermediate – group II and advanced – group III) from the APN project database (cf. Watorek 2004).16

We compare learners' productions with the discourse of French native speakers (our control group) performing the same tasks. This comparison is crucial since our focus is the impact of target language properties (French) on the acquisition of the NP.

The analysis proposed in this contribution is more qualitative than quantitative, centered on the elaboration of the learner variety during language production.

The data of our study consist of film retelling and spatial description produced by 5 participants in each group, 20 participants in total. Thus, the corpus analyzed is composed of 40 discourses, 20–40 utterances each. The data are collected according to the procedure exposed in sections 1.2 and 1.3.

The learners and the native speakers are young adults aged 25-35, graduated at university and from the same social background (middle class). The learners are studying French in a mixed context. They attend language classes and stay (or have stayed in the past) in France. The beginners' proficiency level (group I) corresponds to the basic variety level, detailed in Klein/Perdue (1997). These learners produce utterances, built around a non-finite verb, which are organized into a coherent discourse, following some discourse and semantic principles. The varieties of the intermediate (group II) and advanced learners (group III) correspond to Bartning's (1997) characterization of learners' varieties in the acquisition of L2 French.

The results presented in this section, illustrated by graphs and tables in the appendix, show that the communicative task and, consequently, the type of discourse produced by the learner, determine, at least partially, the acquisition of linguistic means used to mark reference to entities (various types of NP).

Thus, we join the range of studies showing that L2 acquisition reflects a communicative logic (Perdue/Watorek 1998). In fact, learners elaborate the linguistic means at their disposal according to the communicative tasks they face. The context of production, which defines the communicative aims, determines the structure of the discourse produced and the information structure encoded, using increasingly complex means as the acquisition process progresses.

Four main categories of NPs were analyzed in the two types of discourse: bare nouns (N, e.g., attribute, proper noun), pronouns (PRO), full NPs constructed and used according to the rules of the target language (DET+N), and finally, idiosyncratic nominal forms (IL), particularly the inappropriate use of bare nouns.

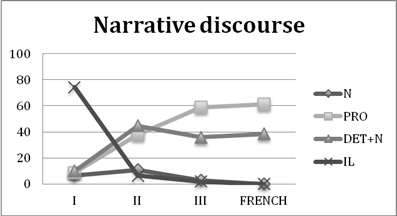

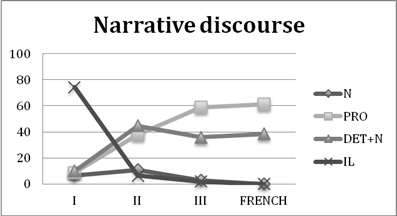

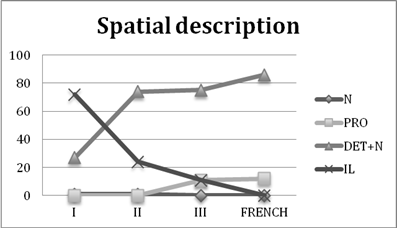

The synthesis of our results, presented in graphs 1 and 2 (cf. appendix, figs. 1-2), shows that the distribution of these forms is somewhat different in the narratives and in the descriptions. The most salient difference is the use of pronouns and full NPs by French native speakers. In narratives, the use of pronouns is dominant compared to the use of full NPs. This proportion is reversed in descriptions.

As expected, as learners progress in acquiring the L2, the percentage of IL sequences decreases and that of the DET+N category increases in both types of discourse. At the same time, the relation between use of full NPs and pronouns follows the tendencies attested in French natives productions. The use of pronouns in narratives increases with improved L2 proficiency. Their use in narratives produced by advanced learners corresponds to native speaker productions. By contrast, pronouns are absent from the descriptions of groups I and II. In descriptions, these forms are only used by learners of group III, showing the same percentage attested in native speaker productions, and a smaller percentage than that of full NPs.

Bare nouns are absent in descriptions and attested in learners’ narratives, exemplified by the dog's proper name (Reksio). This use is a consequence of the film supporting the communicative task, which the Polish learners are familiar with.

Thus, there are differences in the choice of linguistic means according to the type of discourse. If we postulate that these differences depend on the information structure of a given discourse, we have to analyze the relationship between the used forms and their discourse functions. We focus our analysis on two linguistic categories, NPs that follow the structures and rules of the target language (DET+N) and NPs in idiosyncratic forms (IL).

The tables below show the possible internal structures of the two categories.

|

Full NP (DET+N) |

|||||

|

Definite+N DEF+N |

Demonstrative+N DEM+N |

Possessive+N POSS+N |

Indefinite+N INDEF+N |

Numeral+N NUM+N |

Composed NP NP+prep+N |

|

le chien |

ce garçon |

son chien |

une place |

deux voitures |

un bureau de tabac |

Table 1

Thus, the "DET+N" category encompasses nouns with determiners of all kinds: definite and indefinite articles, demonstratives, possessives, numerals (others than indefinite forms un/une). We also include in this category NPs with pre- or post-nominal adjectival modifiers.

|

Idiosyncratic nominal forms (IL) |

|||

|

N without determiner N* |

Adjective+N without det Adj+N* |

Agreement error (Det+N)* |

Non-analyzed forms Others |

|

chien <dog> |

petit chien <little dog> |

ce* statue <this* statue> |

[zãfõ] <enfants ?> |

Table 2

The idiosyncratic sequences in the IL category are acquisition-particular phenomena that can be divided into four subcategories. Bare nouns (N*) correspond to uses where a determiner is obligatory in the target language. The subcategory Adj+N* includes bare nouns pre-modified by an adjective. Full NPs are strings that contain agreement errors between the noun and the determiner in the (DET+N)* category. The subcategory "others" covers all other idiosyncratic, non-analyzed forms. This category includes nominal forms in which the determiner is not analyzed as an independent pre-posed constituent but as part of a lexical item (cf. [zanfo]), and especially, the pronouns in the non-analyzed verbal forms (for example [elvit] in "et [elvit] cette garçon" (et il/elle invite/voit ce garçon 'and he/she invite/see this boy')17.

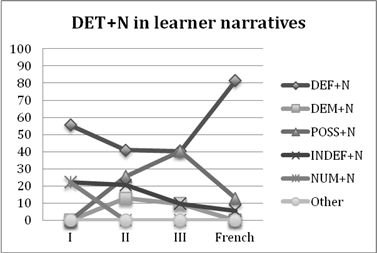

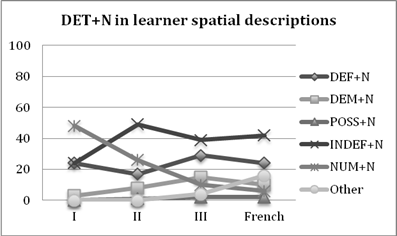

Looking at the distribution of different forms in the DET+N category in native speaker productions (cf. appendix, figs. 3-4), we note that definite NPs ( le+N) are more frequent in narratives, while descriptions show preference for indefinite NPs (un+N).

Similar tendencies are evident in learners' productions as well, where indefinite determiners are clearly more frequent in descriptions than in narratives (cf. appendix, figs. 3-4).

Definite articles in the learners' descriptions do not exceed 30% of the forms from the DET+N category (again in parallel to native speaker productions). On the other hand, indefinite articles and numerals are more frequent. In the narratives, the definite article and possessives are the most frequent determiners.

Preferences in the use of the various NP types in the different types of discourse will be explained through a detailed analysis of these linguistic means in relation to referential movement. In the next section, we show that these choices are linked to precise discourse functions.

3.2 Forms and their discourse functions

Learners of L2 French do not only have to learn the different NP structures available in French, but also how to use them to mark the status of information in discourse, thereby mastering the form-function relations for these structures.

We examine the discourse functions (introduction of entities, maintained reference, change of reference or resumed reference) that the various learners attribute to the forms in the DET+N and IL categories (cf. table 3). Our analysis shows that the acquisition of NP structure in French depends on the discourse functions associated with the various NPs in narratives and descriptions, and enables us to identify diverse acquisitional phenomena, both dependent on the type of discourse and independent of it (cf. below Section 4).

Both protagonists in the film must necessarily be introduced into the narratives, as they are not already given in the context of the communicative task, whereas, in the descriptions, the relatum that refers to the global space in the poster is present in the context of the task and can therefore be left implicit (cf. table 3). This difference stems from the distinction between discourse topic and sentence topic (cf. 1 above). In narratives, the discourse topic corresponds to the global temporal interval, whereas in the descriptions the discourse topic is the global spatial interval corresponding to the high-level relatum (the poster described). Thus, in all narratives analyzed, all the speakers introduce the protagonist referents. Contrarily, in the descriptions, speakers have to introduce thematic entities, but the explicit introduction of relata is rare (cf. table 3) as they form part of the discourse topic.

Introduction of themes and protagonists

French native speakers use the same linguistic construction—the indefinite NP (un+N) —to mark the introduction of themes (in descriptions) and protagonists (in narratives) (cf. tables 5 and 6). However, contrary to the descriptions, the introduction of protagonists can also be realized by a possessive NP (son+N), which marks a relation of ownership between the dog and its master (cf. above, Section 1).

In the descriptions (cf. table 5), the indefinite NP is used to mark introduction, for learners in level II and above, whereas the beginners opt for numerals as well (for example, deux voitures/'two cars'). Learners of both these levels use idiosyncratic forms such as bare nouns with a pre-nominal adjective (category Adj+N*, grand place/'big square'); the idiosyncratic forms in the productions of group III are full NPs with agreement errors (e.g. ce* (cette) statue/'this statue'). Thus, we observe an evolution in learners' use of NPs in the descriptive discourse. The idiosyncratic Adj+N* forms are attested alongside indefinite NPs (in groups I and II) and numerals (in group I). Then, in group III, idiosyncratic forms, such as (DET+N)* showing agreement errors, are attested alongside well-structured French indefinite NPs (the DET+N category).

Contrarily, in the narratives (cf. table 6), only the beginners (group I) use idiosyncratic nominal forms (IL category), bare nouns, mostly with an adjectival pre-modifier (Adj+N*, in 6 of 8 occurrences).

Only two occurrences are full NPs, one of which is the proper noun (Reksio) and the other is an indefinite NP. Learners of groups II and III do not use idiosyncratic forms to introduce the protagonist. In the intermediate group II, introduction is marked by indefinite and possessive NPs (50%, 5 of 10 occurrences, of which 3 indefinite NPs and 2 possessives), compatible with the strategies used by French native speakers. The other 50% of attested forms are NPs containing the definite article or a demonstrative, which are structurally well-formed in the target language, but inappropriate for the discursive context, as they do not mark the introduction of entities in French. This is illustrated in the example below, where the NP cette fille 'this girl' marks the first mention of one of the protagonists.

(5) cette fille rencontre e: à Reksio

<this girl meets e: *to Reksio> 18

Demonstratives are never used in this context in native speaker productions. The demonstrative acquires a deictic value in such a context, which does not correspond to the requirements of the communicative task, as the addressee does not share the speaker's field of view and has no access to the poster.

In the productions of the advanced learners (group III), the forms encoding the introduction of protagonists are indefinite and possessive NPs, as found in native speaker narratives. The difference between the native speakers and the learners consists of the frequency in which these forms are used. Thus, French native speakers prefer the indefinite NP, whereas both forms are almost equivalent in use for group III learners.

Introduction of relata

Reference to relata is mostly left implicit in the descriptions (cf. tables 3 and 4). The first entity introduced, the theme, is introduced and localized in relation to the global space represented in the poster (a high-level relatum). The utterance in the example below is the opening utterance in a description produced by a beginner (group I).

(6) petit place + deux voitures + un vélo

<little square + two cars + a bicycle>

The beginners tend to leave the relatum implicit, thus simplifying their communicative task. Indeed, previous works on the basic variety show that at this stage of acquisition, learners must compromise "between the conceptualization of a complex task such as the construction of a type of discourse, and the linguistic means available" (Perdue 1993b: 1419, our translation).

Thus, learners at this level tend to express only information, which is absolutely indispensable from a communicative point of view. The global relatum (the poster) is given in the context; therefore, the first theme is located with respect to this relatum. Only one intermediate, 3 advanced learners, and 2 native speakers, have introduced this relatum explicitly. The relevant linguistic means can be NPs with a definite value (a noun with a definite article or a possessive) or indefinite NPs. The choice between these forms is determined by the level of familiarity of the relatum and/or by the structure of the larger string into which the NP is inserted (au fond de la place 'at the end of the square' vs. c’est une image avec une ville 'it is an image with a city').

Change of reference occurs in reference to themes in the descriptions, wherein every successive utterance of the foreground introduces a new theme.

In native speaker descriptions, change of theme is primarily marked through the indefinite NP (un+N). However, we also find other types of NPs, such as composed forms (N+prep+N), nouns preceded by numerals and some occurrences of NPs with a definite value (nouns preceded by a definite article or by possessives, cf. table 7).

In the learners' descriptions, the frequency of DET+N forms increases with the higher level of proficiency, and the frequency of idiosyncratic forms decreases accordingly.

The learners primarily use definite NPs and nouns preceded by numerals, similar to the pattern found with native speakers.

However, nouns preceded by numerals are more frequent than indefinite NPs in the descriptions of the beginners. The proportion between both forms is reversed with the higher level of proficiency; in groups II and III indefinite NPs become more frequent than numeral (cf. table 7).

In beginners' descriptions, idiosyncratic forms encode change of reference to themes: bare nouns (79% N*) and nouns with adjectival pre-modifiers (16% Adj+N*). The use of these forms decreases in the descriptions of group II, where 59% of the idiosyncratic forms are full NPs with agreement errors between the indefinite article and the noun (DET+N)*.

Resumed reference to entities concerns both relata in the descriptions (cf. table 8) and the protagonists in the narratives (cf. table 9).

In native speaker descriptions, resumed reference to relata is rare (5 occurrences, table 3). This tendency is also observed in the learners' descriptions (7 occurrences for group I, 3 for group II and 7 for group III). The idiosyncratic forms, primarily bare nouns (N*), are attested in the discourse of group I (5 occurrences) and II (2 occurrences). Learners show a preference for the marking of resumed reference through definite NPs whereas native speakers employ other forms as well.

Resumed reference to the protagonists in the narratives is clearly more frequent than resumed reference to relata in the descriptions (cf. table 3).

Native speakers mark resumed reference in the narratives principally through definite NPs (80.9%, cf. table 9). Some possessives are also attested to mark the ownership relation between the dog and its master, as in introduction cases.

Cases of resumed reference in learners' narratives are limited, although much more common in the productions of groups II and III than in those of the beginners, who regularly alternate between both protagonists.

The idiosyncratic forms are almost absent in this function (6 occurrences in all learners' narratives, all bare nouns). In the DET+N category, the

productions of group II contain

various definite forms (definite articles, demonstratives and possessives), and indefinite NPs. Indefinite forms disappear from the narratives of group

III; however, the choice of definite determiners in their narratives is always different from those used by native speakers, who mark resumed reference

primarily through the definite article (cf. Section 4 below).

As noted above (Section 3.1), maintained reference to entities in French is primarily encoded by pronouns. In this section, we analyze the use of the full NP to mark maintained reference to relata and protagonists.

Native speakers employ different types of DET+N, specifically, definite NPs (le+N) and NPs with demonstratives or possessives.

The beginners' narrative productions show very few occurrences (5) of DET+N forms to mark maintained reference. Instead, they mostly use idiosyncratic Adj+N* forms (cf. table 10), contrary to the intermediate and advanced learners, who mark maintained reference through the same structures employed by native speakers: NPs with definite articles or possessives. The use of the definite article rises with increased proficiency, and the frequency of possessives is reduced accordingly. The difference between the more proficient learner groups and the native speakers is primarily quantitative: learners' productions show a wider range of determiners (definite articles, demonstratives and possessives) than those produced by native speakers, who mark maintained reference to protagonists primarily through the use of the definite article, followed by the use of possessives. A similar tendency is noted in resumed reference to protagonists (cf. above, 3.2.3).

Maintained reference to relata takes place in two types of contexts in the descriptions. The first one is maintaining a topic of one utterance as the topic of the next one, keeping the status of the relatum in the spatial relation 20.

(7) sur l’affiche il y a des immeubles

<on the poster there are buildings>

au centre (de l’affiche) il y a une place

<in the middle (of the poster) there's a square>

In the second context, thematic information expressed in the focus of an utterance (cf. change of reference to themes) can be maintained as relatum in the topic of a following utterance.

(8) au centre de l’affiche il y a une place

<in the middle of the poster there's a square>

sur cette place il y a un kiosque

<in this square there's a news-stand>

Full NPs (DET+N) in native speakers’ descriptions, primarily definite NPs, expresse these two types of maintenance of the relatum. In the descriptions produced by the beginners, idiosyncratic forms such as bare nouns or definite nouns with agreement errors mark maintained reference. These learners use very few forms from the DET+N category. The intermediate learners (group II) also use idiosyncratic forms (11 occurrences of N* forms), but their productions show DET+N forms as well, although primarily demonstrative NPs rather than definite NPs.

The descriptions of advanced learners are similar to those of native speakers, although, as in the narratives, these learners use a wider range of NPs with a definite value compared to native speakers. Aside from the definite article, they also employ NPs with demonstratives and possessives (cf. table 11).

As pointed out in the previous sections, the main issue of our study concerns the influence of the properties of two types of discourse, narrative and spatial description, on the acquisition of NP structure and the determination system in L2 French.

According to our hypothesis, the order of acquisition of the determination system in French depends on the context of discourse production and consequently on the type of discourse the learners have to produce. The results detailed in section 3 allow us to identify an acquisitional path dependent on the type of discourse (cf. Section 4.1.).

However, our results also allow us to identify phenomena independent from the type of discourse, which we discuss in section 4.2. Thus, our hypothesis is partially confirmed at least.

We can also explain these results in terms of a possible influence of the source language, Polish, in the light of other works on the same types of discourse in L2 French produced by learners of other source languages (cf. 4.3.)

The general difference between the linguistic means implemented in the types of discourse presented in section 3.1, was explained in section 3.2 with the detailed analysis of the relations between these forms and their functions in the considered types of discourse. NPs with an indefinite value, such as un+N and numeral+N, are much more frequent in descriptions than in narratives. We have shown that the use of these forms is determined by the marking of the introduction of referents and change of reference, moves that are more common in descriptions. The information structure of the narrative in the domain of entities is based on the introduction of protagonists whose reference is then either maintained, or updated, but change of reference is not characteristic of this type of discourse. On the other hand, in descriptions, the introduction of thematic entities and reference shifts must be systematically marked by NPs with an indefinite value.

The DET+N category, a NP containing a definite article, a possessive or a demonstrative, is attested in narratives to mark maintained and resumed reference to protagonists. The information is already known in the context and must be updated. In these two cases, the marking is typically made by determiners with a definite value (cf. tables 12 and 14). In the productions of the beginners studied (group I), there is no resumption of reference to the protagonists. These narratives are rudimentary and the percentage of definite NPs is relatively small. As shown in table 4, continuation in narratives of group I essentially corresponds to maintained reference.

In narratives, indefinite NPs serve primarily to mark the introduction of reference to protagonists (cf. table 6) and are sporadically attested in the cases of resumed reference. On the other hand, in descriptions, the organization of information in discourse leads to a more frequent use of NPs with indefinite articles or with numerals. Except for the introduction of reference to themes (cf. table 5), a considerable number of nouns preceded by an indefinite article or a numeral is attested in change of reference contexts (cf. table 7). Indeed, every foreground utterance in descriptions expresses a spatial location where the information to the relatum is generally maintained in topic, and the information to the theme, the entity to be located, has to change systematically in focus for the description to make progress. A noun with an indefinite article or a numeral encodes every new thematic entity.

As shown in table 7, the proportions between the two indefinite NPs (with a numeral or an indefinite article) change according to the learner's proficiency. The learners of group I use the numeral form more frequently, while those of groups II and III prefer the indefinite article, thereby approaching the pattern of the native control group. Thus, the use of numerals can constitute a stage preceding the acquisition of the indefinite value of the article.

The idiosyncratic forms mainly attested in the learners' production are bare nouns without any article (N*) and bare nouns modified by an adjective (Adj+N*). Although, the analysis of these forms shows characteristics independent from the type of discourse and reflects a process of general complexification of the learners' variety (see section 4.2), we also find some elements which differentiate the performance of the two tasks in L2. The learners assign the function of marking new information in the context to modified bare nouns. This rule is evident especially in the beginners' production, where the percentage of these forms is considerably higher than in the productions of groups II and III (cf. figures 1 and 2). The intermediate (II) and advanced learners (III) continue to use this form in descriptions to mark changes of reference to themes (cf. table 7), but almost never do so in narratives. So, the information structure specific for descriptions, where the expression of spatial localization implies repeated marking of changed reference to thematic entities, leads to a high frequency of indefinite NPs mastered in L2, as well as to the extended use of idiosyncratic nominal forms, like Adj+N*.

This result also suggests that the acquisition of the indefinite NP is more complex than the acquisition of the definite NP. When discourse context motivates the marking of maintained and resumed reference, the learners quickly learn to use NPs with determiners that mark a definite value; N* in this context is essentially used by group I. On the other hand, in a discourse context that requires the marking of a change of reference, we witness the persistent use of idiosyncratic means, used alongside NPs with an indefinite value (indefinite article and numerals).

Altogether, the analysis of the learners’ productions shows that they elaborate linguistic means according to the discourse context. Each learner produced both types of discourse and used variable linguistic means according to the communicative task he had to deal with. So, the choice of NPs for reference in narratives and in descriptions is controlled by the information structure encoded. Thus, the acquisition of linguistic means is determined by the specific communicative needs of these tasks.

Two tendencies are clearly visible in the analyzed data. First, the analysis of the idiosyncratic means used to refer to entities shows a complexification of the learners' variety independent of the type of discourse (i). Secondly, with respect to the DET+N category and full NPs, we observe a diversification in learners' productions in the use of determiners with a definite value (the definite article, demonstratives, possessives) in contexts where native French speakers employ the definite article alone (ii).

(i) Whatever the type of discourse, idiosyncratic nominal forms are the most frequent in the beginners' productions (group I). The use of these forms decreases sharply in groups II and III.

The bare noun (N*) and the bare noun modified by an adjective (Adj+N*), seem to be endowed with precise discourse functions. N* is used particularly to mark maintained reference (cf. tables 10 and 11) and resumed reference to entities, relata (cf. table 8) and protagonists (cf. table 9). Indeed, 76.4% of the idiosyncratic forms in beginners' narratives and 60% of these forms in descriptions made by these same learners correspond to N* marking maintained reference to entities.

(9) /Es/ chien (N*>introduction)

</Es/ (=it's) dog>

chien (N*>maintaining) /sErEvEje/

<dog wake up>

chien (N*>maintaining) /ak/ petit garçon (Adj+N*>introduction)

<dog /ak/ little boy>

chien (N*>maintaining) garçon (N*>maintaining) /promEnE/

<dog boy go for a walk>

(10) à côté /fontan/ /sE/ dame (N*>introduction)

<next (to) /fontan/ it's lady>

à côté dame (N*>maintaining) /sE/ immeuble

<next (to) lady it's building>

The use of Adj+N* is more regularly attested in contexts of introduction or change of reference. It is found in the introduction of themes and protagonists (tables 5 and 6) and in the change of reference to themes (cf. table 7).

(11) en face kiosque (N*>maintaining) est petit boutique (Adj+N*> change)

<in front (of) news-stand is little shop>

(12) petit chien (Adj+N*>introduction) /abitE/ avec sa maison

<little dog live with his house>

We must underline that N* can be used to mark a change of reference (table 7) while Adj+N* can be used in the case of maintained/resumed reference (tables 9 and 10). However, these uses are rare.

It is interesting to note that both occurrences of bare nouns (N*) to mark the introduction of referents are attested in post-verbal position, with a verbal lexeme corresponding to a non-finite verbal form (cf. 'basic variety', Klein/Perdue 1997).

(13) /Es/ chien

</Es/ (=it's) dog>

On the other hand, the Adj+N* sequence appears either in utterances lacking a verb, or as subjects in preverbal position.

(14) petit chien et petit garçon

<little dog and little boy>

(15) petit chien habite sa maison côté grand maison

<little dog live his house side big house>

Thus, we postulate that, in the basic learners' variety of L2 French (cf. Klein/Perdue ibid.), the bare noun is specialized as a form marking maintained reference to entities, unlike the noun modified by an adjective. If this form is used to introduce a referent, it is given in a postverbal position, marking its new information status through word order.

The form Adj+N* is associated with the function of marking introduction and change of reference. The addition of an adjective to a bare noun constitutes an idiosyncratic means to indicate that this information is not a part of the context. At the more advanced levels, represented in our study by learners of groups II and III, the idiosyncratic forms N* and Adj+N* disappear in favor of (DET+N)* constructions, where the noun is accompanied by an article, although involving agreement errors between the elements. At the same time, forms of the DET+N category increase and multiply, allowing for a more effective marking of information status.

(ii) The higher the proficiency, the more is maintained reference marked by full NPs (of the category DET+N). Regardless of the discourse type, we note that in all contexts in which French native speakers prefer to mark maintained and resumed reference by a definite NP (Def+N), learners of groups II and III use NPs with other definite determiners, such as possessives and demonstratives. This is the case in marking the introduction of protagonists (cf. table 6) and in resumed reference to protagonists and relata (cf. tables 8 and 9), as well as in maintained reference to protagonists and relata (cf. tables 10 and 11). So, in the introduction of protagonists, the relation between the dog and the boy allows for the introduction of one of them through the possessive. Contrary to the pattern found in the production of groups II and III, only a single occurrence of the possessive son+N was attested in the productions of French native speakers (the definite article was used in the majority of cases).

Maintained reference to protagonists and to relata is marked by the definite article in the production of French native speakers, and less often by the possessive and the demonstrative. As for the reference to protagonists, the comparison between group III and the native speakers shows that the learners use a range of definite NPs to indicate maintained reference, whereas the leading form in native speaker productions is le+N (88%, cf. table 10).

Maintained reference to relata reveals a similar phenomenon, already visible in the productions of groups I and II, although with few occurrences (cf. table 11). In group II, the use of demonstrative to mark maintained reference is more frequent than the use of the definite article. In group III, we see the same percentage of nominal forms with a definite article as in the native speaker production. However, these learners also use possessive and demonstrative NPs, whereas French native speakers prefer the definite article (54%), followed by the demonstrative (27%).

Certain results reviewed in sections 4.1 and 4.2 allow us to note the possible influence of the source language, Polish, on the way the learners handle the French determiner system.

We submit to discussion three points, which arise from our analyses:

1. a large number of bare nouns (N*) in group I productions and the marking of introduction by postverbal N*;

2. a higher use of numerals compared to the indefinite article in group I descriptions;

3. the use of various types of definite determiners instead of the definite article in the productions of intermediate and advanced learners.

In the absence of the same types of productions by learners with other source languages, crosslinguistic remarks must be based on the results of other studies, including some, which were presented in sections 1.2 and 1.3. This comparison is necessary as some of these may be learning strategies that stem from the properties of the TL, French, and independent of the learners' LS.

(i) Bare nouns are common in the productions of beginner learners. Although this result can be interpreted as indicative of the influence of Polish, other studies examining the productions of learners with other source languages (whether with or without articles) find the same result in the production of their beginners. This is the case of Japanese learners (Trévisiol 2003) for whom bare forms are the preferred strategy to introduce specific referents, and of young bilinguals (Catalan/Castilian) learning English in a school context (Muñoz 1997).

Bare nouns used to mark the introduction of referents are systematically placed in postverbal position. In the absence of indefinite local marking, learners rely on word order, which may be due to the influence of the source language. As specified in section 1.2, unlike the strategy employed by French native speakers, in the narratives of Polish native speakers, the introduction of protagonists is encoded through a NP-subject that follows a lexical verb in a foregrounded utterance.

(16) rano wstaje pies

morning gets up dog-Nom

<in the morning the dog gets up>

In narratives of French native speakers, reference to protagonists is introduced in a background utterance, using a presentational structure.

(17) c’est l’histoire d’un chien

<this is the story of a dog>

(ii) Table 8 shows that beginner learners tend to use numerals to mark a change of reference (67%). This percentage quickly decreases in the more advanced groups. This phenomenon could be explained by the influence of Polish, in which the numeral jeden 'one' serves as an optional determiner marking new information. Given the ambiguity of the French form un as a numeral or an indefinite article, the num+N category only included numerals starting with 'two'. The elevated use of numerals by learners of all three groups and by French native speakers leads us to wonder to what extent the use of un in groups I and II really corresponds to the indefinite article.

Thus, in the process of acquiring the indefinite article as a marker of the introduction and change of reference in French, these learners undergo a stage in which they establish equivalence with their source language before incorporating a grammatical class that is absent in this language.

(iii) The use of definite determiners by Polish learners to mark maintained reference could also be understood as the influence of the SL. In fact, in Polish, optional determiners, as the demonstrative or the possessive, can express definiteness. Advanced learners master the constraint requiring obligatory determiners in French, but its use is costly, as it is a grammatical category that is absent in their SL. On the other hand, the possessive and the demonstrative fill the same discourse function in L2 and have equivalents in the SL. Watorek (2003) obtains similar results in her analysis of anaphoric links in the L2 French descriptions produced by Polish learners (cf. section 1.2). We can contrast this study with another study (Watorek 1998) concerning L2 French descriptions produced by Italian learners, where the use of the demonstrative does not differ from that of French native speakers. Similarly to Watorek (2003), Sleeman (2004) notes that Japanese learners of French tend to overuse demonstrative NPs in definite discourse contexts (the SL, Japanese, has no articles, but determiners are reserved for deictic use).

In our view, results (ii) and (iii) reflect the conceptualization of definiteness specific to the SL of these learners, Polish, which does not possess the obligatory category of the article. Intermediate and advanced learners perceive the obligatory nature of determination in French. However, they prefer to use determiners, which have equivalents in their own SL. So, the possessive and the demonstrative (optional definite determiners in Polish) substitute the definite article, while the numerals replace the indefinite article. This tendency concerns both types of discourse, although we also find some differences that are due to the type of communicative task and to its support. Indeed, the introduction of protagonists in narratives is marked by a possessive as there is a relation of ownership between the dog and its master (or the master and his dog) which is never the case in the descriptions. Also resumed reference in narratives can be marked by the possessive for the same reason, whereas this form is never attested in the descriptions as marking change of reference, in particular to themes. Furthermore, demonstratives are more frequent in the context of maintained reference to entities in descriptions whereas the possessive is the dominant form in narratives.

This article supplies some elements allowing the redefinition of the acquisitional path of NP structures in L2 French, postulated in the previous works (cf. section 1.3), according to which the acquisition of the definite value of the French determiner appears earlier compared to the indefinite value expressed by the indefinite article. Comparison of the results of previous studies on NP acquisition and our own analysis of the narratives and the descriptions allows us to put in perspective the precocity of the acquisition of the definite article compared with that of the indefinite article. We suggest the following order in the acquisition of the determination system in L2 French.

The bare noun, incompatible with the rules of the TL, would be multifunctional in the very early stages of acquisition, a result that is also evident in the study of pre-basic varieties (cf. ESF project, Perdue 1993a). This tendency is still evident in the productions of our beginner learners, although a specialization of the function of N* is already established. So, learners at the basic variety level begin to identify N* as a way to maintain reference, as opposed to Adj+N*, which is used to mark the introduction or change of reference. Learners at the intermediate level use more and more full NPs with various types of determiners, depending on the status of information that they need to mark in the discourse. Contrary to previous studies, definite and indefinite determiners appear at the same time in our learners' variety. Their frequency of use varies according to the communicative task and the type of discourse produced. Definite determiners, namely the definite article, the possessive and the demonstrative, are systematically used to mark the maintained and resumed reference. On the other hand, indefinite determiners, such as the indefinite article and the numerals, mark the introduction or change of reference. In the later stages of acquisition, learners have to match various forms (within the class of definite and indefinite determiners) with different values. So the use of the definite article increases in the production of advanced learners, although their productions still differ from those of French native speakers with respect to the choice of the article on one hand and the possessive and demonstrative on the other. The same is true for the class of indefinite determiners. The indefinite article is attested more and more systematically, disregarding its numeral function.

Generally, we can postulate the following tendency for the acquisition of the form-function relation in the domain of the entities in L2 French: the more grammaticised the learners' variety becomes, the more the learners differentiate the linguistic means according to their discourse context. The evolution of the multifunctional idiosyncratic nominal forms that are the most frequently used by beginners into more complex NPs in the post-basic varieties, goes hand in hand with the specialization of these NPs in the marking of information status. The Adj+N* category, productive in the learners' variety, is a very good example. In the absence of the article category, a lexical item (adjective) is used to indicate that the information changes with respect to the context.

This study shows that the context of production, which determines the properties of a discourse, influences the acquisition of the linguistic means. The same learners, in a given stage of acquisition, can produce different forms according to the type of information that must be marked in each type of discourse. Thus, the same beginner learner who produces few indefinite NPs or none at all in a narrative, is capable of producing these forms in a description. The absence of a form in a certain type of production does not mean that it is absent in the learner's L2 system. Thus, the consideration of various types of contexts of production is imperative to properly describe the acquisition of linguistic means.

Studies of NP acquisition in French (cf. section 1.3.) have been based primarily on narratives and free conversations, and more rarely on descriptions and instructional discourse. However, in all cases, these studies did not systematically compare how the same individuals in various types of discourse acquire the French NP system.

Works in L2 acquisition (Perdue 1993) have shown the importance of the learners' communicative needs in the constitution of a new system. So, "the analysis of the input made by the learner obeys (…) a recognizable communicative logic which is reflected in its production, and which is characterized by a regular structuration (…)", (Perdue and Watorek, 1998, p. 143). Two kinds of factors determine L2 acquisition: communicational factors recovered from the context of production, and the structural factors connected to the linguistic properties of the target language.

So, the informational factors appear to play a leading role in the acquisition process. The learner develops linguistic means to achieve complex communicative tasks in the most effective way possible. But, acquisition is also constrained by structural factors arising from the formal properties of the target language. These factors "shape" the acquisition process.

In our study, communicational factors correspond to different informational characteristics in narratives and descriptions. The structural factors are recovered from the constraints of the French system of nominal determination. So, communicational factors connected to the context of production of narratives and descriptions urge the learners to elaborate linguistic tools that will allow them to express the relevant information in the domain of the entities, and the structural factors, the complexity of NP structure in French, are the constraints which lead to the production of more and more complex nominal forms in L2.

Ahrenholz, Bernt (2000): "Modality and Referential Movement in Instructional Discourse: Comparing the Production of Italian Learners of German with Native German and Native Italian Production". Studies in Second Language Acquisition 22/3: 337–368.

Aleksandrova, Tatiana (2012): "Reference to Entities in Fictional Narratives of Russian/French Quasi-Bilinguals". In: Watorek, Marzena/Hickmann, Maya/Benazzo, Sandra (eds.): Comparative Perspectives on Language Acquisition. A Tribute to Clive Perdue. Bristol etc., Multilingual Matters: 520–534.

APN Project Database (Project "Construction of Discourse by Learners, Adults and Children"): available online: http:// www.mpi.nl/resources/data, accessed 10.10.2013.

Bartning, Inge (1997): « L’apprenant dit avancé et son acquisition d’une langue étrangère. Tour d’horizon et esquisse d’une caractérisation de la variété avancée ». Acquisition et Interaction en Langue Etrangère 9: 9–50.

Benazzo, Sandra (2004): « L’expression de la causalité dans le discours narratif en français L1 et L2 ». Langages 155: 33–51.

Carroll, Mary/ Stutterheim, Christiane von (1993): "The representation of spatial configurations in English and German and the grammatical structure of locative and anaphoric expressions". Linguistics 31: 1011–1042.

Carroll, Mary/von Stutterheim, Christiane (1997): « Relations entre grammaticalisation et conceptualisation et implications sur l’acquisition d’une langue étrangère ». Acquisition et Interaction en Langue Etrangère 9: 83–116.

Carroll, Susanne E. (1989): "Second Language Learning and the Computational Paradigm". Language Learning 39: 535–594.

Carroll, Susanne E. (1999): "Input and Second Language Acquisition: Adult's Sensitivity to Different Sorts of Cues to French Gender". Language Learning 49/1: 37–92.

Givón, Talmy (1979): On Understanding Grammar. Ch. 5, Syntactization. New York: Academic Press.

Hendriks, Henriëtte (1998a): "Reference to person and space in narrative discourse: a comparison of adult second language acquisition and child first language acquisition". Studi Italiani di Linguistica Teorica e Applicata 27/1: 67–86.

Hendriks, Henriëtte (1998b): « Comment il monte le chat ? En grimpant ! L’acquisition de la référence spatiale en chinois, français et allemand L1 et L2 ». Acquisition et Interaction en Langue Etrangère 11: 147–190.

Hendriks, Henriëtte (1999): "The acquisition of temporal reference in first and second language acquisition: what children already know and adults still have to learn and vice versa". Psychology of Language and Communication 3/1: 41–60.

Hendriks, Henriëtte (2000): "The acquisition of topic marking in Chinese L1 and French L1 and L2". Studies of Second Language Acquisition: 22/3: 369–398. (=Special Issue on the structure of learner varieties)

Hendriks, Henriëtte (2005): "Structuring space in discourse. A comparison of Chinese, French, German and English L1 and French, German and French L2 acquisition". In: Hendriks, Henriëtte (ed.): The structure of learner varieties. Berlin, Mouton de Gruyter: 111–156.

Hendriks, Henriëtte/Hickmann, Maya (1998): « Référence spatiale et cohésion du discours : acquisition de la langue par l’enfant et l’adulte ». In: Pujol Berché, Mercé/Nussbaum, Luci/Llobera, Miquel (eds.): Adquisición de lenguas extranjeras : perspectivas actuales en Europa. Madrid, Edelsa: 151–163.

Hendriks, Henriëtte/Hickmann, Maya (1999): "Cohesion and anaphora in children’s narratives: a comparison of English, French, German, and Chinese". Journal of Child Language 26: 419–452.

Hendricks, Henriëtte/Watorek, Marzena/Giuliano, Patrizia (2004): « L’expression de la localisation et du mouvement dans les descriptions et dans les récits en L1 et en L2 ». Langages 155: 106–126.

Hendriks, Henriëtte/Watorek, Marzena (2008): « L’organisation de l’information en topique dans les discours descriptifs en L1 et en L2 ». Acquisition et Interaction en Langue Etrangère 26: 149–172.

Klein, Wolfgang (in press): "Information structure in French". In: Manfred Krifka/ Renate Musan (eds.): The expression of information structure. Berlin/New York, Mouton de Gruyter.

Klein, Wolfgang/Perdue, Clive (1997): "The Basic Variety (or: Couldn’t natural languages be much simpler?)". Second Language Research 13: 301–347.

Klein, Wolfgang/Stutterheim, Christiane von (1991): "Text structure and referential movement". Sprache und Pragmatik 22: 1–32.

Klein, Wolfgang/Stutterheim, Christiane von (2005): "How to solve a complex verbal task: Text structure, referential movement and the quaestio. In: Rose, Miriam/de Paula, Brum/Sanz Espinar, Gema (eds.): Recherches sur l’acquisition des langues 30/31: 29–67.

Kuroda, Shigeyuki (1990): "Cognitive and syntactic bases of topicalized and nontopicalized sentences in Japanese". In: Hoji, Hajime (ed.): Japanese/Korean Linguistics: 1–26.

Lambert, Monique/Carroll, Mary/Stutterheim, Christiane von (2008): « Acquisition en L2 des principes d’organisation de récits spécifiques aux langues ». Acquisition et Interaction en Langue Etrangère 26: 11–31.

Lambert, Monique/Lenart, Ewa (2004): « Incidence des langues sur le développement de la cohésion en L1 et en L2 : étude de la gestion du statut des entités dans une tâche de récit ». Langages 155: 14–32.

Lenart, Ewa/Perdue, Clive (2004): « L’approche fonctionnaliste : structure interne et mise en œuvre du syntagme nominal. » Acquisition et Interaction en Langue Etrangère 21: 85–121.

Lenart, Ewa (2006): Acquisition des procédures de détermination nominale dans le récit en français et polonais L1, et en français L2. Etude comparative de deux types d’apprenants : enfant et adulte . Thèse de doctorat, Université de Paris 8: http://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00124849, accessed 21.01.2014

Muñoz, Carmen/Nussbaum, Luci (1997): « Les enjeux linguistiques dans l'éducation en Espagne ». Acquisition et Interaction en Langue Etrangère 10: 12–31.

Perdue, Clive (1993a) (ed.): Adult language acquisition: cross-linguistic perspectives. Volume II: The results. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Perdue, Clive (1993b): « Comment rendre compte de la ‹ logique › de l’acquisition d’une langue étrangère par l’adulte ». Etudes de Linguistique Appliquée 92: 8–22.

Prodeau, Mireille (1998): « La syntaxe dans le discours instructionnel en LE ». Acquisition et Interaction en Langue Etrangère 11: 95–146.

Prodeau, Mireille/Carlo, Catherine (2002): « Le genre et le nombre dans des tâches verbales complexes en français L2: grammaire et discours ». Marges linguistiques 4: 165–174.

Stutterheim, Christiane von (1997): Einige Prinzipien des Textaufbaus: Empirische Untersuchungen zur Produktion mündlicher Texte. Tübingen, Niemeyer.

Trévisiol, Pascale (2003):Problèmes de référence dans la construction du discours par des apprenants japonais du français, L3. Thèse de doctorat, Université de Paris 8: http://www.bibliotheque-numerique-paris8.fr/eng/ref/103344/134104560/, accessed 21.1.2014.

Trévisiol, Pascale/Watorek, Marzena/Lenart, Ewa (2010): « Topique du discours / topique de l’énoncé – réflexions à partir de données en acquisition des langues ». In: Chini, Marina (ed.): Topic, information structure and acquisition. Franco Angeli: 177–194.

Véronique, Daniel et al. (eds.) (2009): L’acquisition de la grammaire du français, langue étrangère. Paris: Didier.

Watorek, Marzena (1996): « Le traitement prototypique : définition et implications ». Toegepaste Taalwetenschap in Artikelen 55: 187–200.

Watorek, Marzena (1998): « Postface : la structure des lectes des apprenants ». Acquisition et Interaction en Langue Etrangère 11: 219–244