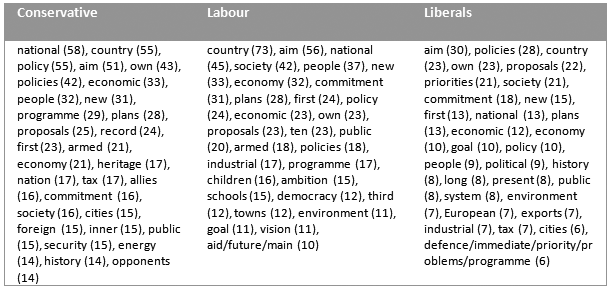

Table 1: Top-twenty keywords in the manifesto corpus (function words in bold with log-likelihood scores)

http://dx.doi.org/10.13092/lo.65.1402

For some years now, researchers within the field of Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) have been using corpus linguistics methods in their work. The development of corpus-assisted critical discourse analysis (cf. Baker 2009) is reflected in the addition of a chapter on corpus linguistics (CL) in the second edition of the highly influential collection Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis (edited by Wodak and Meyer 2010). In her chapter, Gerlinde Mautner claims that CL methods can be used in CDA projects to enrich research design and assist with the interpretation of results (2010: 125). She demonstrates this with a collocational profile of the adjective unemployed in a 60-million-word corpus of articles from The Times newspaper and reveals that the top-ten collocates with the highest t-scores are an, are, people, who, and, term, long, million, for, workers. In her discussion of this list she makes an interesting assertion, the implications of which are central to the present study. According to Mautner, function words such as an, are, who, and and for "are devoid of separate meaning" and "tend not to be as interesting to discourse analysts as to grammarians, and it is generally safe in a CDA setting to ignore them" (ibd.: 126). It is a slightly strange claim to make, especially when – on the very next page – Mautner herself presents concordance lines from The Times corpus in which unemployed is linked to other adjectives by and, resulting in binomials such as unemployed and desperate and unemployed and homeless. In performing this function, and is helping to construct a particular representation of unemployment in The Times, in which the state of worklessness is routinely associated with a range of other states carrying what Mautner calls a "negative semantic load" (ibd.: 127). Here, and might be "devoid of separate meaning" (ibd., my italics), but it is certainly implicated in the creation of meaning at the phraseological level. This raises questions about the other function word collocates of unemployed in Mautner's list. Does its co-occurrence with for indicate that people who cannot find work are positioned as the beneficiaries of something (as in "X for unemployed people"); does it reflect that the length of time a person has been out of work is particularly salient in the construction of the discourse of unemployment (as in "she has been unemployed for X months")? Does the presence of who in the list signal that noun phrases containing human social actors characterized as unemployed are frequently post-modified by relative clauses with who? The fact that such potentially interesting questions are provoked by a cursory examination of function word collocates indicates that a decision to omit them from an analysis is potentially problematic.

In this article I offer an alternative perspective on these apparently "uninteresting" lexical items. I show how a focus on key function words can offer insights into the representation of ideology in a corpus of UK election propaganda: political meanings and values which might not have been accessible if – as Mautner recommends – only the apparently semantically "richer" lexical words had been considered. The fact that much CDA work is concerned with exploring aspects of discourse which are not immediately obvious to the casual reader (thus rendering their effects more powerful ideologically) means that function words must be worth considering in corpus-assisted critical discourse analysis.

In the following section I describe the manifesto corpus. Then in Section 3 I consider the nature of function words, arguing for their inclusion in corpus-assisted CDA and outlining the analytical methods used in this study. The remainder of the paper presents the findings of my analysis and conclusions.

The corpus of texts under consideration consists of the manifestos produced by the three main political parties in the UK between 1900 and 2010: nearly six hundred and seventy thousand words of political propaganda, representing over a century of party policy at twenty-nine general elections.1 During this period, the nature of election manifestos has changed in some important ways. Most obvious and striking is their increasing length. In the eleven elections between 1900 and 1935, the three parties between them produced approximately fifty thousand words of text in thirty-three manifestos. In the 2010 election alone, the word count for the three manifestos was just under seventy-seven thousand. Increasing length is associated with changing emphases. For example, in the period before the Second World War, the Conservative and Liberal2 manifestos were presented in the form of electoral addresses by the party leaders, while the very earliest Labour manifestos were little more than collections of socialist slogans. Only in the 1920s did manifestos begin to be seen by the parties as a means of setting out a coherent political programme; and it was not until the election of 1945 that the manifestos of all three parties first began to resemble those we are now familiar with. Today, the stereotypical British election manifesto consists of an introduction (often in the form of a personal address by the party leader) followed by sub-sections outlining policies in the main domains of social life such as health, education and defence. If the manifesto is by the party challenging for power it will often contain a critique of the governing party's record. Technological advances mean that the later manifestos make more use of colour and visual imagery than the earlier ones.

Election manifestos play a central role in British politics. Their publication, which in modern times has often been accompanied with massive media publicity, provides a repository of "authoritative statement[s] of what the party plans to do in government". More generally, manifestos can also "strike a popular mood", such as Labour's 1945 and 1964 manifestos which promised "social and economic reconstruction" and "modernisation of the economy" respectively (Kavanagh 2000: 7). Through their "textual emphases", manifestos often "set the tone and themes of campaign discussion" (Budge 1999: 2), and after the election they are used as a reference point by the party, its political opponents, and the media to confirm that election promises have been fulfilled, or to claim that they have been broken. No other single document regularly produced by a political party has this degree of power and influence, so it is no surprise that manifestos have attracted the attention of politically-oriented discourse analysts (see Pearce 2004; Charteris-Black 2006; Aman 2009; Edwards 2012; Chaney 2013).

Lexical words and function words are often defined in opposition to one another, with the former tending to occupy the conceptually positive pole of a binary opposition. Lexical words (i. e. nouns, lexical verbs, adjectives, and adverbs) are described by Biber et al. (1999: 55) as the "main carriers of meaning" in a text or speech act, in contrast to function words (i. e. determiners, pronouns, auxiliary verbs, prepositions, adverbial particles, coordinators and subordinators), which are regarded as semantically empty. Lexical words can function as the head of a phrase, whereas function words generally cannot. Lexical words can be long and morphologically complex, unlike function words which are usually short and morphologically invariable. Lexical words often receive stress in speech while function words are generally unstressed; and they form a large and ever-expanding open-class, whereas there are a small and finite number of function words (closed-class). The only "positive" thing that function words seem to have going for them is that they are very common! (see Biber et al. 1999: 55; Stubbs 2001: 40–41). Such schematised accounts serve to present function words in a lesser light than lexical words. However, the neat theoretical division "between meaningful and meaningless words" implied in such accounts "is not supported by the empirical research findings that have emerged in recent decades from the field of corpus linguistics" (Groom 2010: 61). These findings have informed the development of a theory of language as "phraseology" (Sinclair 1991, 2004; Hunston and Francis 2000; Hoey 2005). At the heart of this approach is the notion that "the word is not the best starting-point for a description of meaning" because "meaning arises from words in particular combinations" (Sinclair 2004: 148) – that is, meanings are located in sequences of words and not in the individual words making up these sequences. And since function words are central to the phraseological sequences through which meaning is conveyed, they must be a valid object of interest in discourse analysis (whether traditional or corpus-assisted), the point of which is "to identify the conventional meanings and values expressed" in texts (Groom 2010: 61).

The academic journals most associated with CDA routinely publish articles which demonstrate the "research synergy" (Baker et al. 2008: 274) between CDA and CL. And despite Mautner's doubts about the usefulness of function words, not all corpus-assisted studies have ignored them entirely. Work of note includes Rayson 2008 (would and our in the 2001 Labour and Liberal Democrat election manifestos); O'Halloran 2010 (paragraph-initial but in a corpus of UK newspaper articles about immigration); Weninger 2010 (to and and in a corpus of US redevelopment discourse); Mulderrig 2012 ( we in UK education policy discourse). McEnery's 2006 monograph on swearing also considers function words such as will and and in corpora associated with policing so-called "bad language" in the seventeenth and twentieth centuries in Britain. By adopting an inclusive approach in relation to function words, these studies illustrate their potential significance in critical studies, and my research represents a contribution to this expanding field.

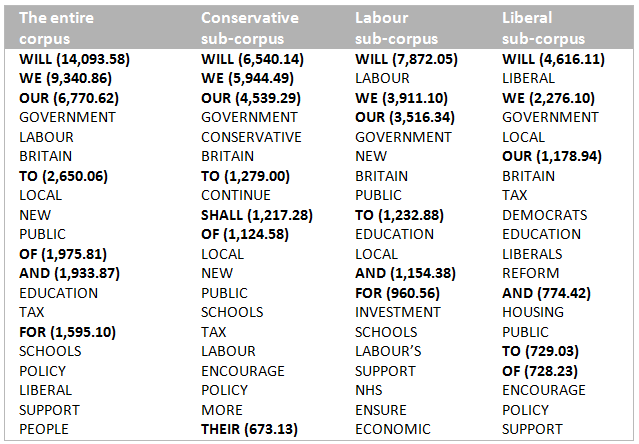

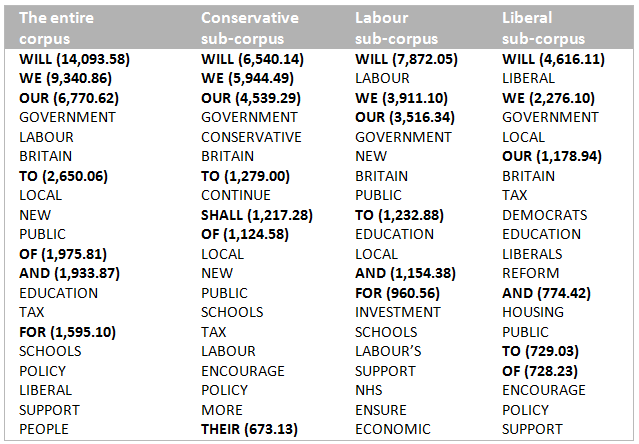

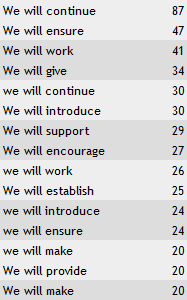

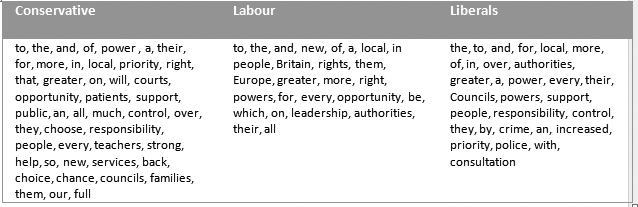

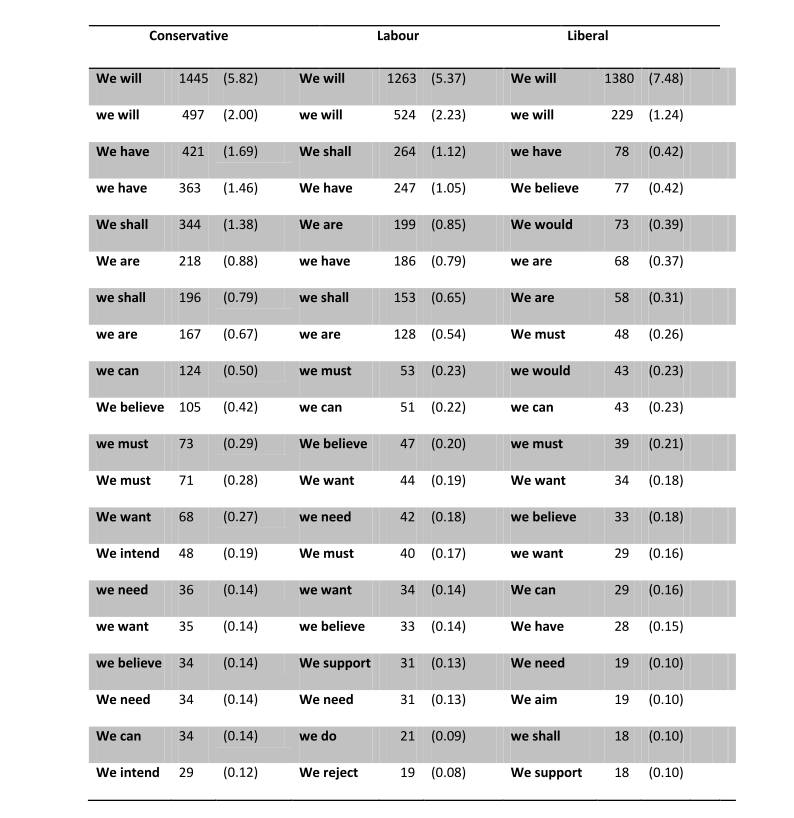

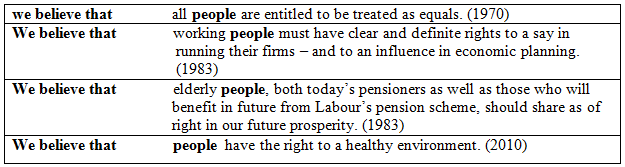

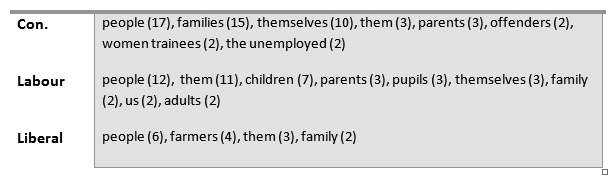

In their range of approaches and emphases, these studies also illustrate the methodological eclecticism which has always been a feature of corpus-assisted approaches to discourse features (Mautner 2010: 142). Here I adopt a similarly open and exploratory stance, the outline of which I sketch below. But first I explain how the function words at the heart of this study were selected for analysis. This paper adopts a well-established inductive procedure in CL by identifying those function words in the corpus that are statistical keywords. In this way, the objects of study "float to the surface as a result of statistical processing" (Scott/Tribble 2006: 108). Rather than being pre-selected the items emerge automatically from the analysis and provide a "point of entry" into a corpus (Baker 2010: 133). Table 1 is my entry point: it shows the top-twenty keywords in the corpus as a whole and in each sub-corpus, measured against the BNC sampler and ordered by strength of the log-likelihood score. These words have been derived using the KeyWords function of Scott's WordSmith Tools 5.0 (measured against the BNC sampler). I use the log likelihood statistic because, according to Scott (2010: 168) it gives a better estimate of keyness than the chi-square test when, as in this case, a whole genre is being contrasted against a reference corpus.

Table 1: Top-twenty keywords in the manifesto corpus (function words in bold with log-likelihood scores)

My main tool for the interrogation of the corpus is Sketch Engine: a powerful corpus query system which uses the high-level query language known as CQL (Kilgarriff et al. 2004).3

This article focuses on will, we, our and to because they are the four keyest function words in the corpus, and the only function words to occur amongst the top-twenty keywords of all three parties (see Table 1). The aim of the analysis is to examine the phraseologies in which these key function words occur, in order to assess their role in the construction of party ideology. I show that although superficially similar phraseological choices are often made by all three political parties (largely as a consequence of the generic constraints operating on the writers of the manifestos), a closer inspection of the patterns of co-occurrence4 entered into by the key function words can reveal contrasting party political positions and orientations. In order to draw out the political significance of these phraseologies, I interpret them in relation to a "widespread" and "universally understood" distinction in political ideology: what Noël and Thérien (2008: 55) call the "left-right value divide". In western societies, for the last two hundred years, this divide has helped "citizens integrate into coherent patterns their attitudes and ideas about politics." On the left are people who are generally optimistic about human nature, who value social protection and equality, and have an inclusive and communal vision of society and culture which attracts them towards political policies designed to increase social justice and encourage international cooperation and understanding. People on the right, on the other hand, generally view society and culture as exclusive and nationalistic, have a high regard for the military, tend to value competition above cooperation and are usually meritocratic and individualistic in outlook, often voting for policies which they believe will result in increased opportunity within a de-regulated, low tax and fully marketized economy (cf. Noël/Thérien 2008: 24; McCandless 2010: 14–15). These core values "organize the way most people think about a host of social choices", ranging from attitudes towards homosexuality and abortion to the way children should be brought up (Noël/Thérien 2008: 55). In the UK party context and relative to each other, the Conservatives are on the right, Labour is on the left, and the Liberals have traditionally occupied a left-of-centre position.

If, in its broadest sense, politics is the process of "organizing social power in communities" (Volpi 2006: 445), then political ideology is the framework of beliefs and values which underlie, arrange, and inform the organization of power. Therefore, overt statements of political ideology such as election manifestos will inevitably refer to the various groups of social actors involved in these power relations, in particular the political party producing the manifesto and the members of the public who are often represented as the potential beneficiaries of the proposed political actions of those parties. Consequently, many of the phraseological patterns which emerge relate to the representation of human beings as they act, or are acted upon.

In the sub-sections which follow I describe the phraseological behaviour of the target words by focusing on patterns of co-occurrence. As well as being of interest in themselves, these patterns are also "diagnostic", in the sense that they point to areas of potential interest which may repay closer attention using the more "traditional" techniques of Critical Discourse Analysis.

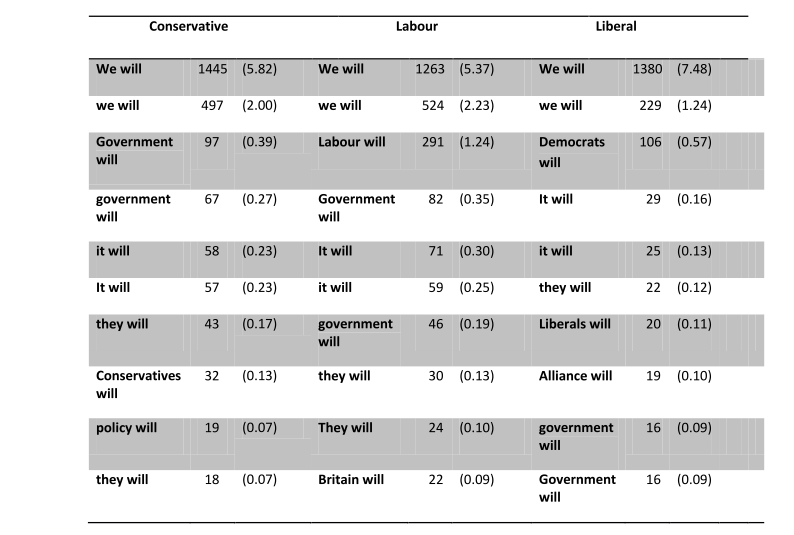

The modal verb will is the keyest word in the corpus as a whole, and also heads the keyword lists for all three parties, occurring 16.67 times per thousand words in the corpus, compared with 2.62 per thousand words in the BNC sampler. The six-fold difference is explainable when we consider the function of manifestos. The Oxford English Dictionary describes a manifesto as a written or spoken "public declaration...proclamation...explanation, or justification of policy issued by a head of state, government, or political party or candidate, or any other individual or body of individuals of public relevance, [such] as a school or movement in the Arts". It seems then, for a manifesto to be recognized as such, it must contain a declaration of the intentions of the individual or group producing the manifesto. This means that we might expect patterns involving intrinsic (or deontic) meanings of will to be common. According to Biber et al. (1999: 485), intrinsic meanings refer to "actions and events that humans (or other agents) directly control: meanings relating to permission, obligation, or volition (or intention)." There are "two typical structural correlates of modal verbs with intrinsic meanings: (a) the subject of the verb phrase usually refers to a human being (as agent of the main verb), and (b) the main verb is usually a dynamic verb, describing an activity or event that can be controlled." (ibd.) How common are these "typical structural correlates" in the manifesto corpus in relation to will? We can get a sense of this by searching for all occurrences of will where it is preceded by a noun or pronoun. Table 2 clearly shows the relationship between will and corporate human agency in manifestos, with high frequencies of nouns referring to groups of political actors (in the form of the parties' names, or references to the government). But what is particularly striking here is the frequency of we will. In the sequence noun/pronoun + will, the pronoun we occurs 5,338 times: over fifty-six per cent of all occurrences (compared with 324 times for government will). The sequence we will is the most frequently occurring two-word cluster in the corpus, occurring nearly sixty times more frequently than it does in the BNC sampler (8.05 times per thousand words compared with 0.14 per thousand words).

Table 2: Top-ten occurrences of noun/pronoun + will (raw frequencies and normed frequencies per 1000 words)

In most cases, we in we will is being used to refer exclusively to the party producing the manifesto (i. e. "we the Conservative Party"): in random samples of 100 occurrences of we will in each party manifesto, there were two instances of inclusivity in the Labour manifestos, one in the Liberal manifestos and none in the Conservative (I will consider issues of inclusivity and exclusivity in subsequent sections). The table also reveals the rhetorical prominence of this sequence in the corpus: nearly seventy-seven percent of occurrences are sentence-initial, sometimes in lengthy sequences of anaphora, as in We will let families keep more of what they earn. We will support marriage. We will provide choice and high standards in schools (Con. 2001).

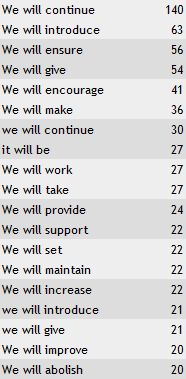

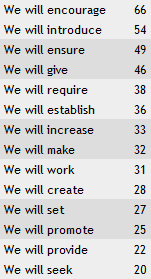

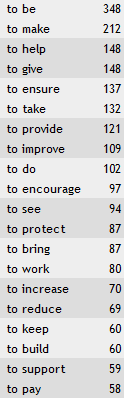

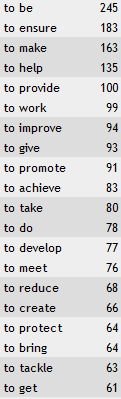

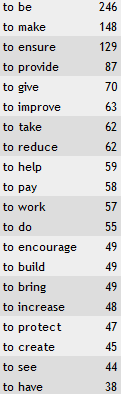

I now turn to Biber et al.'s second structural correlate of will: "the main verb is usually a dynamic verb, describing an activity or event that can be controlled." Table 3 lists the top-twenty most frequent sequences of we will + the base form of a lexical verb in the three sub-corpora.

|

Conservative |

Labour |

Liberals |

|

|

|

All of them convey the notion not only that it is possible for the subject ("we") to carry out the action of the main verb, but also that the subject is willing and intends to act. The list poses a number of intriguing questions. For example, what is to be made of differences in the relative frequencies of we will continue? It occurs 0.69 times per thousand words in the Conservative manifestos, 0.50 in Labour and just 0.04 times in the Liberal texts. Presumably, this reflects the political history of the period under consideration, with the lower frequency in the Liberal texts related to the fact that without political power, there are no policies enacted in the past to be continued into the present. (It might also be worth noting that continue is the eighth most key word for the Conservatives, suggesting that continuity is an important Conservative value.) The extent to which the Conservatives give prominence to this sequence can also be seen in the fact that 82.3 percent of its occurrences are sentence- initial, compared with 74.3 percent for Labour. These cross-party differences in we will + verb have potential ideological interest. Central to politics are ideas about the distribution of resources and powers among different social groups, which means it is always worthwhile considering what resources and powers are being distributed, who is receiving them and to what ends. An insight into this can be seen when we look at we will give. Give is an interesting verb to consider because "the act of giving has a relatively rich structure in so far as it involves (typically) three easily distinguishable entities: the GIVER, the RECIPIENT, and the THING being transferred" (Newman 1996: 33). Since here, in all cases the giver is we (the corporate entity of the party producing the manifesto), I will concentrate on the recipient and the thing being transferred.

Table 4: Collocates of we will give (in a span of ten to the right of the node at 3+ frequency)

Give is usually used ditransitively: that is, it is capable of taking both a direct and an indirect object, as in I will give them [indirect object] their tea [direct object]. A structure which is semantically equivalent to this involves the use of a prepositional object (in the form of a to-phrase), as in I will give their tea to them. For the purposes of this analysis, these alternatives are conflated. Table 4 lists collocates of we will give occurring three times or more in a search horizon of ten places to the right of the node. This span potentially captures elements of both the direct and indirect object, as can be seen in the table, where collocates such as people are the semantic recipients, and collocates such as right are the thing(s) being transferred, as in We will give people a new right of access to open country (Lab. 1992). However, because I am interested in the transference of possession of various entities to human social actors I need to be aware that not all the collocates in Table 4 suggest (either singularly or collectively) human recipients, as exemplified in We will give full support to the EEC proposals (Con. 1979). Therefore, in the next stage of the analysis I exclude such non- relevant semantic patterns by focusing on a particular syntactic structure. A favoured pattern in the corpus with we willgive is to have the direct object consisting of a head noun taking a to-clause, as inWe will give every patient the power to choose any healthcare provider (Con. 2010). Since "the common head nouns taking to-clauses represent human goals, opportunities or actions" (Biber et al. 1999: 653), and since human goals, opportunities and actions are at the centre of politics, this is a potentially fruitful structure to consider. In section 4.4 I consider to-clauses in general, but for now I focus on the nouns occurring after we will give followed by a to-clause (see Table 5).

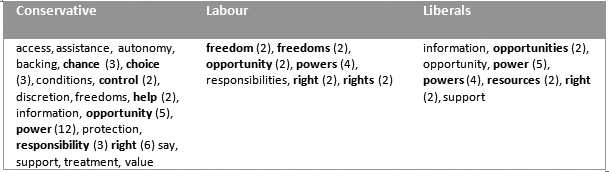

Table 5: Nouns in W(w)e will give + noun+ to-clause

There are interesting party differences here, most obviously that the Conservatives favour this construction more than Labour and Liberals, employing a wider range of head nouns, and more of them. A sense of the political uses made of this structure by the Conservatives can be gathered from the concordance lines when we focus on two head noun lemmas used most often in the corpus in this structure: RIGHT and POWER.

The giving of a right or power implies that the political party pledging to do so perceives that that right or power is currently not enjoyed by the particular social actor(s) or institution(s) presented as potential beneficiaries. It is therefore an implied critique of current conditions, and as such can reveal what a party deems to be a significant absence in a particular social domain. In relation to identified groups of social actors the Conservatives focus on the domains of health and education, and claim that we will give:

As is the case with we believe that in relation to people, the Conservatives' right-wing values and policies are reflected here: in particular, the notion of "choice" in public services, whether for the potential beneficiaries of these services (parents, patients) or providers (doctors, GPs). As a response to the economic crises of the 1970s, many governments around the world started to force state enterprises to function on a profit-making basis; some were privatized completely. During the 1980s and 1990s, "neoliberal ideological commitments led governments to push privatization and marketization even to sectors that remained natural monopolies or that were widely perceived by the public to be public services which should not be governed by market principles, such as education and health care" (Huber/Stephens 2005: 614–15). In the 1980s and 1990s it was the Conservatives who were particularly wedded to the idea that market forces might make the provision of public services more efficient, responsive, and flexible, although New Labour under Tony Blair was equally as enthusiastic in many respects.

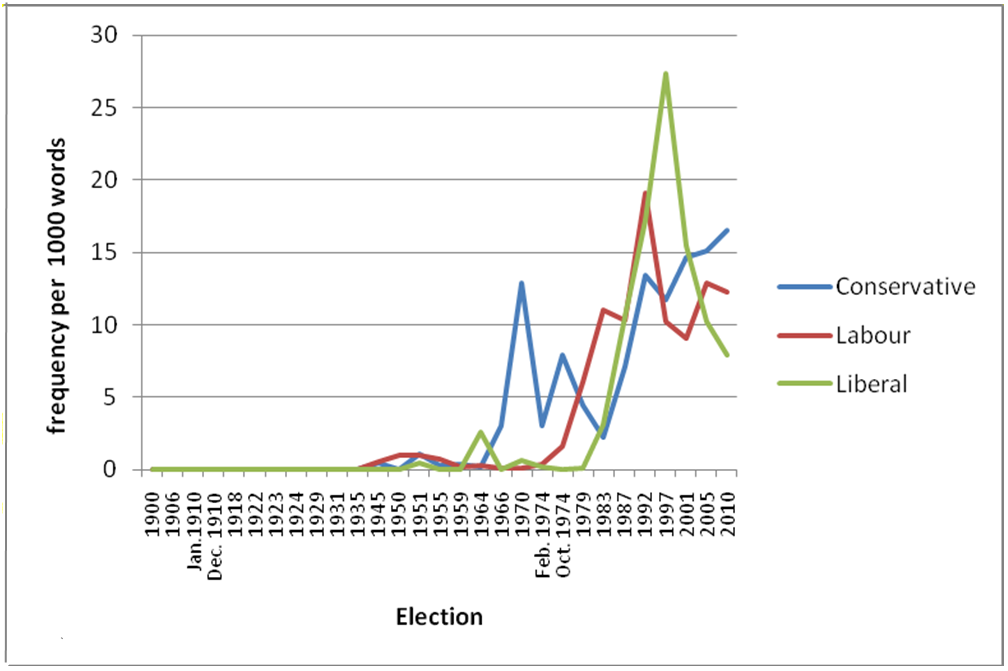

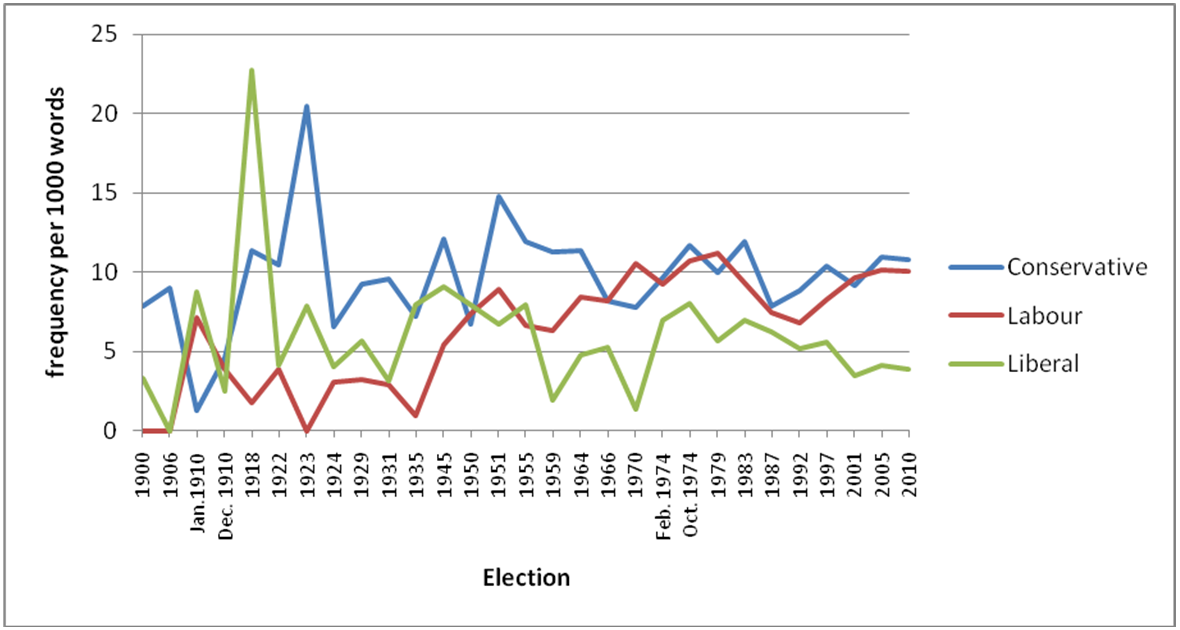

So far in this discussion of we will I have shown how the we almost universally refers to the collective voice of the party producing the manifesto and that when we consider the main verb following will, and more extended sequences involving the direct object of the main verb, sites of potential ideological difference emerge. But is we will a stable feature of the genre of election manifesto over time? It does not seem to be. A clear increase over time in the occurrence of we will is evident in Figure 1. In the eleven elections between 1900 and 1935, this sequence does not occur at all; between 1945 and 1964, it is somewhat infrequent (0.43 occurrences per 1000 words); between 1966 and 2010 it occurs 8.37 times per 1000 words, but it should be noted that this is a period of volatility, with peaks of usage reached for all three parties in 1992 (Labour), 2001 (Liberal) and 2010 (Conservative). This frequency information points to the changing nature of manifestos over time. The move away from the manifesto being presented as the electoral address of the party leader meant that exclusive uses of we (representing the corporate voice of the party) become more frequent; furthermore it is only in the period after the Second World War that all three parties use the manifesto as a means of setting out detailed and developed programmes for government containing frequent statements about what the party will do, should it win the election. Both factors increase the likelihood of we will being deployed.5

Figure 1: Occurrences of we will per 1000 words by election

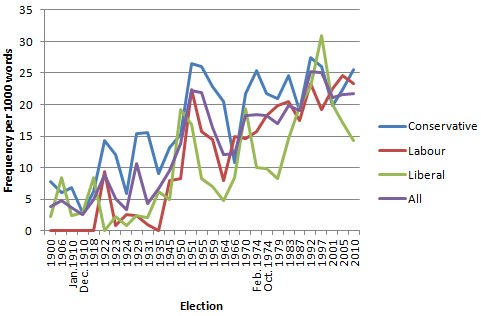

Whereas we will, as we have seen, is associated with the 1960s onwards, we in general is more widely dispersed across the corpus. Figure 2 plots we over time.

Figure 2: Occurrences of we per 1000 words by election

The general trend seems to be one of increasing use (the peak for all three parties occurs in the period 1992–2010), and this broadly coincides with Mulderrig's (2012: 706–708) findings in her corpus of UK education policy documents from the period 1972–2005, in which the increasing frequency of we (together with the decline in third person forms such as the government) is interpreted as a discursive outcome of a new mode of government self-identification which began during the period of New Labour and which is related to a general trend in recent decades towards the personalisation and democratisation of public discourse (cf. Pearce 2005; Fairclough 1992). In her analysis, Mulderrig (2012: 709) examines the rhetorical potential of we, showing how its referential complexity can be manipulated for persuasive ends. This is particularly the case when it is used inclusively: that is, when the speaker/writer and the addressee/reader are bound together within a shared deictic frame of reference, so helping to establish solidarity and social bonding. Although there are some instances of we being used in this way in the manifesto corpus – as in We are a great nation, with a long and eventful history behind us (Con. 1974 February) – it is usually used by the party producing the manifesto to refer to itself exclusively: Since we took office we have started on the long process of modernising obsolete procedures and institutions (Lab. 1966). This exclusive we is more common in the corpus than the inclusive we. Ninety-seven percent of Liberal and ninety-six percent of Conservative uses were found to be exclusive; the figure was slightly lower for Labour at eighty-nine percent.6 However, this does not mean that the potential of referential ambivalence has not been exploited in the corpus, as we shall see in relation to our.

Syntactically, the subject pronoun we typically precedes a verb phrase. Table 6 lists the twenty most frequent sequences of we followed immediately by a modal, primary or lexical verb. Setting aside the most common sequence (we + will) which I considered separately in 4.1, the results point to intriguing contrasts in frequency. For example, we have occurs 3.17 times per thousand words in the Conservative sub-corpus and 1.87 in the Labour sub-corpus, but only 0.58 times in the Liberal texts. The difference between Conservative and Labour on the one hand and Liberal on the other is possibly an artefact of the political history of the UK. Most instances of we have in the corpus (67.1 percent) occur in the perfective structure we + have + past participle, as in We have regulated demand through selective measures (Lab. 1966). The perfect aspect usually indicates that a past situation has some effect on, or relevance for, the present (Huddleston/Pullum 2005: 49); in this example, the implication is that the regulation started in the past and is still continuing. A political party is more likely to claim that it has done something in the past if it has been in power at some point, particularly if it is still in power. It is Conservative and Labour who have had the greatest share of power over the last century or so, most obviously in the period after the Second World War. Between the elections of 1945 and 2010, Conservative Prime Ministers led governments for approximately thirty-five years and Labour for thirty. The possible effect of incumbency on perfect aspect use can be seen when relative frequencies of we have in "incumbent" and "opposition" manifestos are compared. For example, since 1950 the Conservatives have been in power at ten elections, and in those manifestos we have occurs 4.32 times per thousand words compared with 0.91 times in the seven manifestos produced when they were not in power. Contrasts in the relative frequencies of we would might also have a similar origin. In the Liberal manifestos we would is nearly sixteen times and eight times more frequent per 1000 words than it is in the Labour and Conservative manifestos respectively. The overuse of would by the Liberal Democrats in the 2001 manifesto has also been observed by Rayson (2008: 535), and was interpreted as a consequence of the Liberal Democrats not expecting to win the 2001 general election, and therefore favouring more tentative expressions of future intentions.

Table 6: Top-twenty occurrences of W(w)e + modal verb, primary verb or lexical verb (raw frequencies and normed frequencies per 1000 words)

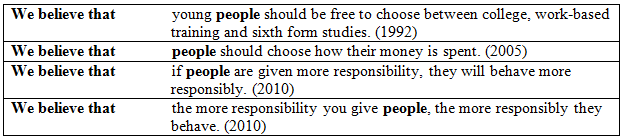

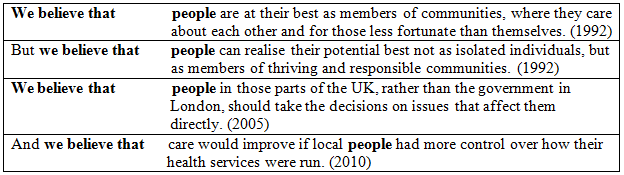

We might also consider the wider context of the full lexical verbs collocating with we. The most frequent lexical verb for all three parties in this position is the stative mental verb believe. An examination of what a political party explicitly states as a belief is potentially revelatory of that party's ideology. Believe is often followed by a complement that-clause containing the content of the beliefs, as in "we believe that all men are created equal". The most frequently occurring noun collocate of we believe that for all parties is people. What do the parties believe in relation to people? For the Conservatives what we believe is associated with core right wing notions of freedom of choice and individual responsibility (Figure 3); but in relation to we believe that, such sentiments are not expressed by Labour.

Figure 3: Examples from concordance lines showing we believe that with people in the subsequent subordinate clause (Conservative manifestos)

Figure 4: Examples from concordance lines showing we believe that with people in the subsequent subordinate clause (Labour manifestos)

Figure 5: Examples from concordance lines showing we believe that with people in the subsequent subordinate clause (Liberal manifestos)

Instead, the language of rights and entitlements (in the context of social care and equality) is used (Figure 4). The Liberals convey a sense of community, localism and individual liberty (Figure 5). For each party we see how the same sequence (we believe that), combined with a high frequency collocate (people), is associated with different ideological positions. Analogous contrasts emerge throughout this study, illustrating the potential advantages of using key function words as a point of entry for the analysis.

After will and we, the third most key function word is our. Again, its statistical significance is a consequence of the functions performed by a manifesto. On the one hand, the voice of a manifesto has a corporate dimension, in the sense that it speaks for a political party, setting forth its policies and ideology. At the same time, the manifesto attempts to speak for the country and its people (Britain and people are both among the top-twenty corpus keywords), suggesting that its particular view of the world is the common-sense one. This means that what is determined by our – just as what is referred to by we – is sometimes exclusive, sometimes inclusive, and sometimes ambiguous. But unlike we, inclusive uses of our outnumber exclusive uses.7 Figure 6 reveals that over time use of our is quite volatile (particularly between 1900 and 1974), with a general tendency in the post-Second World War period for the Conservative and Labour party to use it more than the Liberals. However, this takes into account only the distribution of the form. In order to gain an insight into meaning, what is determined by our needs to be considered.

Figure 6: Occurrences of our per 1000 words by election

Table 7 shows the most frequent sequences consisting of our + any word. Some uses of our are clearly exclusive. For example, the lists contain a set of determiner + noun sequences with overlapping senses related to the intentions of the political party behind the manifesto: our aim, our policy, our plans, our proposals, our policies, our programme.

Table 7: Top thirty our + any word sequences in each sub-corpus

An examination of these gives an insight into possible changes in the nature of the election manifesto over the course of the twentieth century. For example, our policy is quite evenly distributed, occurring at least once in 44.8 percent of the manifestos between 1906 and 2010, but our policies does not make its first appearance until 1950. The earliest appearance of our programme is 1922. Our aim and our proposals appear first in 1935; and our plans in 1945. What these dispersions seem to be reflecting is the shift in emphasis of the genre which I identified in relation to we and we will: over time the manifesto becomes a document which sets out a developed and coherent political programme. It is also interesting to note changes in the rhetorical presentation of policy items. Before 1979, no party uses the phrase our commitment, but it has been used in every election since then. We might also note the appearance of our ambition and our vision in the Labour list, which occur only from 1992 onwards. Commitment, ambition and vision suggest a discourse of modern management, of the sort found in texts like the so-called 'mission statements' of large organisations. Such phraseological patterns point to a rhetorical shift in the presentation of the nature of the relationship between a party and the electorate, and also a party and its own policies.

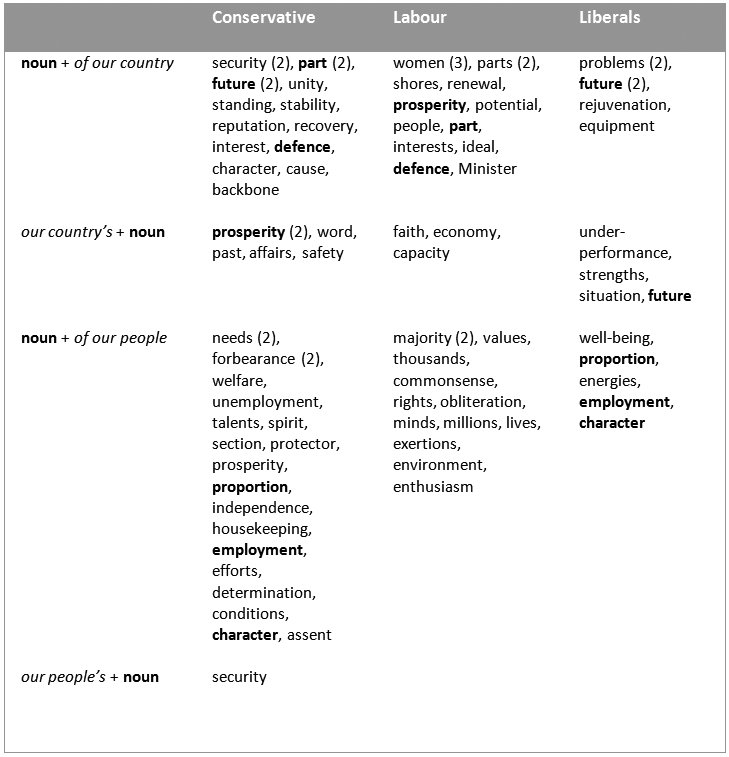

Some aspects of the frequency and ranking of items in Table 7 suggest party differences in emphasis in relation to inclusive uses of our. These include the presence of our environment in the Labour and Liberal lists and its absence from the Conservative list; the fact that our children, our schools and our democracy occur only in the Labour list, while our heritage, our allies, and our security appear only in the Conservative list, and the absence of our history in the Labour list. These variations in frequency are possibly indexical of positions on a left-right political continuum, with left of centre parties tending to conceptualize the environment as shared by all, seeing children as the responsibility of the whole community rather than parents alone, and claiming/possessing democracy. On the other hand, right of center parties – in relation to what is "ours" inclusively – display nostalgia and a concern with military alliances and security. But it is also revealing of political ideology to consider the similarities between these lists. In order to demonstrate this, I will focus on the sequences our country and our people. How are these items being used politically across the three sub-corpora? We can check this by looking at two syntactic forms with similar semantic roles: the noun in the sequence noun + of our country/people and the noun preceded by the genitive noun phrases our country's/people's (see Table 8).

In relation to of our country/our country's, Conservatives favour nouns associated with defence (security, stability, defence, safety). Both Labour and Conservative refer to the prosperity of our country, but it is only the Conservatives who evoke its standing, reputation, word, character and backbone. The characteristics conveyed in these nouns are often applied to human beings: standing, word and backbone are bodily in the sense that their basic meanings are associated with human posture, speech and anatomy, while in contemporary English, character and reputation are also mainly qualities applied to human beings. Here we see the deployment of the conceptual metaphor "a state is a person" (Lakoff 1993: 243). Such modes of thought are common in everyday life, as well as in the domain of politics (cf. Wendt 2004: 289), but to conceive of a nation as a person inevitably emphasizes unity, coherence, shared values, and so on (since the human body is usually experienced as an indivisible whole), rather than diversity, complexity and nuance. The metaphor of the state as a person, from Hobbes's Leviathan onwards, perhaps fits more comfortably with a right-wing world view than it does with a left-wing one. It is also interesting to note the particular aspects of personhood which the Conservatives apply to our country. Standing and reputation are external valuations of worth; while word is also outward facing (people "give" their word to others). Backbone is a rather old-fashioned term implying strength, but also fortitude; it also has a "moral" dimension. This sort of language conveys tradition, honour, stoicism – values which perhaps tend to find particular favour with people at the conservative end of the political spectrum.

Table 8: Nouns preceding of our country/people and following our country's/people's

As we might expect in a future-oriented genre such as a manifesto, all three parties look ahead, referring to our country's future and potential; but only the Conservatives refer to our country's past. Furthermore, only the Liberals convey an element of critique ( our country's problems, our country's under-performance) – a strategy which makes sense for a party that had enjoyed, until 2010, only a very limited share of power since the 1930s.

In respect of our people, many of the collocations are broadly positive: the Conservatives have "forbearance", "talents", "spirit", "determination" and "character"; the Liberals also evoke the "character" of "our people", while for Labour "our people" have "values", "commonsense" and "enthusiasm". As with our country, the Conservative choices here – in particular forbearance and spirit – have a slightly archaic quality, suggesting a more elevated rhetorical style, of the kind evident in relation to "our country".

The key function words I have considered so far owe their saliency to the generic conventions of the manifesto: a document written as the collective voice of a political party (we), demonstrating its shared values with the electorate (our), while committing itself to action (will). The final function word in my analysis is also implicated in creating the generic "flavor" of a UK election manifesto. If we look at the most frequently occurring clusters with four or five words, including one or more of we, will and our we see that they often contain to: "we will continue to"; "we shall continue to"; "will be able to"; "we are committed to"; "we are determined to"; "our aim is to"; "we will seek to"; "we will work to".

|

Conservative |

Labour |

Liberals |

|

|

|

In these examples, to is a marker introducing infinitive clauses and it is this function which I focus on here, rather than its use as a preposition. The infinitive clause is a non-finite subordinate clause with a variety of roles. Table 9 shows the top-twenty sequences consisting of to followed by the base form of a verb. Thirteen to + verb structures occur in all three parties' lists: to + be, bring, do, ensure, give, help, improve, make, protect, provide, reduce, take, work. There are positive meanings associated with most of these words; meanings which are more or less explicit (help, improve, protect) or present as a consequence of a positive semantic prosody ( ensure, provide). But once the contexts of these sequences are considered, do political differences emerge? In order to attempt an answer I am going to focus on to help. Helping is a core political concept; indeed, all political actors in a democracy want to represent themselves as helping. But different political parties often have contrasting attitudes towards who gets helped and for what reasons. In general English, where to help occurs, the beneficiaries of assistance are often represented in a noun phrase following the verb, as in "I want to help you". Table 10 lists all the nouns and pronouns with human referents occurring at least twice in a span of ten to the right of to help. Many of these are the semantic beneficiaries of the verb.

Table 10: Human beneficiaries of to help (occurring at least twice in a span of 10 to the right of the node in the same sentence)

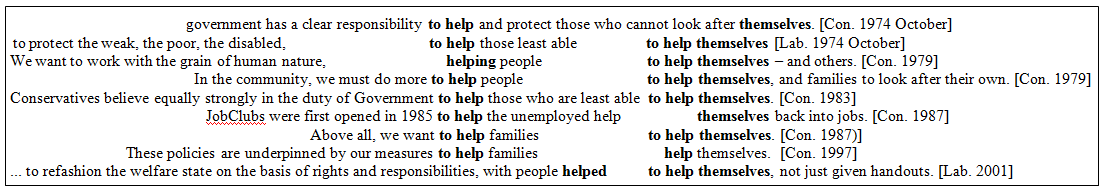

There are some potentially interesting contrasts here in relation to frequency and rank (including the Conservative emphasis on families and Labour's concern with children), but once again a consideration of context can be revelatory. For example, the reflexive pronoun themselves appears in the Conservative and Labour lists, and the concordance lines reveal how it co-occurs with to help in a highly political way (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Examples of themselves co-occurring with to help in Conservative and Labour manifestos

These examples show contrasts in how to help themselves is incorporated into political discourse. The first – which is often associated with a left of centre outlook – conveys the idea that government should directly help vulnerable people, for example: "those who cannot look after themselves"; "those who are least able to help themselves". The second – which is sometimes favoured by people on the right of politics – implies that government should provide people with the wherewithal and conditions to enable them "to help themselves". Significantly, the help on offer is qualified – potential recipients have to show that they are deserving of the assistance given, and the help they receive is "reward for approved social conduct" (Williams 1976: 46). It is clearly the Conservatives who favour the deserving beneficiaries of help, and noteworthy that when Labour refers to people 'being helped to help themselves, not just given handouts', it is in 2001 during Tony Blair's period of shifting the Labour party to the right.

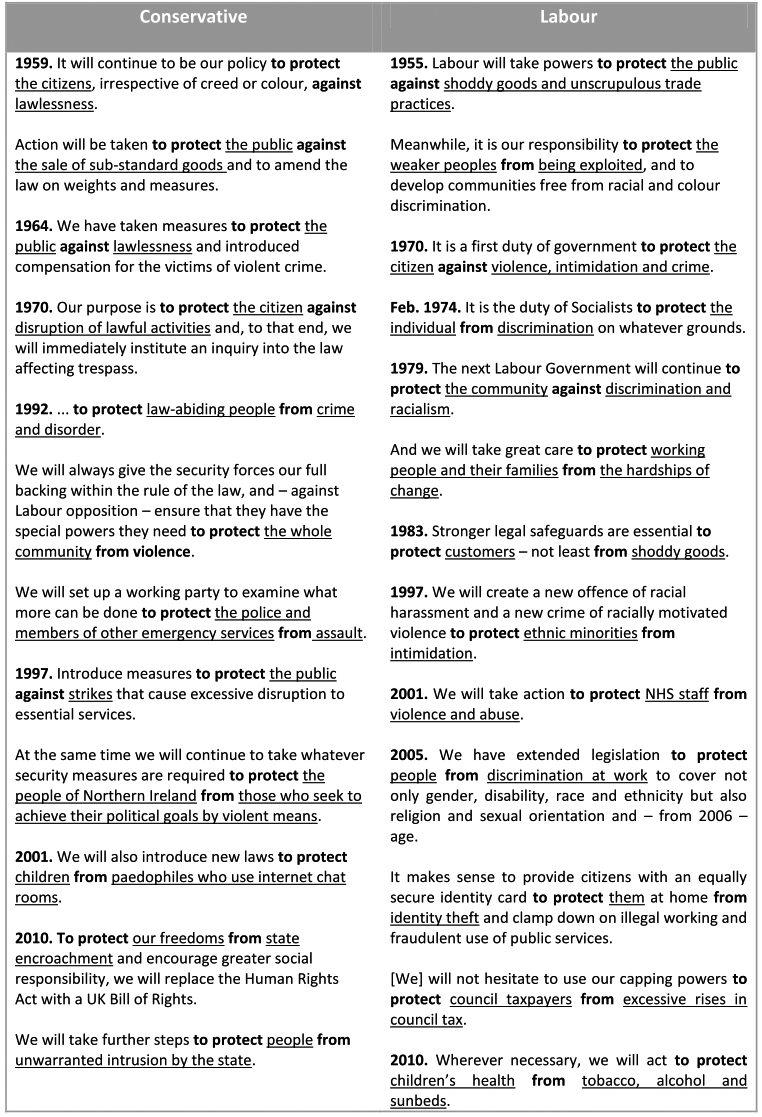

To protect is also worth looking at from the perspective of human beneficiaries. To this end I focus on structures where to protect combines with an adverbial element introduced by against or from, as in We have taken measures to protect the public against lawlessness (Con. 1964). Concordance lines reveal notable contrasts between Conservative and Labour in relation to the law (since it is through the law that governments most clearly offer protection to people). As Table 11 shows, both parties pledge to protect people against/from crime, violence, exploitation and disruption of various kinds, but only Labour cites forms of discrimination on the grounds of race, ethnicity, gender and disability as something people are to be protected against (1955, Feb. 1974, 1979, 1997, 2005); and only the Conservatives offer protection against the threat of industrial action (1970, 1997) and intrusion by the state (2010).

Table 11: To protect + against/from in the Conservative and Labour sub-corpora

For reasons of economy, I have had to limit my analysis to the four keyest function words in Table 1. But I have shown how even this relatively short list of targets can provide sufficient evidence to vindicate an approach which places function words at the centre of a corpus-assisted discourse analysis. By using key function words to reveal potentially salient phraseological sequences, I have uncovered aspects of the beliefs and values of the parties producing the manifestos which might have remained hidden otherwise. The analysis has pointed to ways in which function words are implicated in the representation of human beings in relation to political values and actions. For example, for the Conservatives the sequence we believe (in the context of the high-frequency collocate people) is associated with traditional right-wing values such as freedom of choice and individual responsibility, in contrast to Labour, who express more left-of-centre beliefs in social care and equality, and the Liberals who champion localism and democracy (indeed local is the fifth most key word in the Liberal sub-corpus). Similarly, the theme of Conservatives valuing the freedom of individuals to make choices is evident in relation to sequences where we will give occurs in the context of right(s) and power(s), where these rights and powers are invoked in relation to choice in public services – a marked right-wing value. A focus on the infinitive marker to also reveals contrasts, with to help used by the Conservatives in a context where the recipients are presented as deserving in some way, and to protect (when it occurs with an adverbial element introduced by from or against) used by Labour in contexts where discrimination on the grounds of race and gender are represented as threats (in contrast to the Conservatives, who perceive threats in the shape of industrial action and state intrusion). Finally, what is determined by inclusive our can reveal what the political party behind the manifesto wants to present as a shared value or commodity, and these co-occurrences in turn often reflect a right-left value divide, with the Conservatives claiming shared values in relation to aspects of history, heritage and the military, whereas the more left-leaning parties focus on concepts such as democracy, the environment and social care. Additionally in relation to our, contrasts are evident when it precedes people or country, with the Conservative manifestos more likely than the others to employ a conceptual metaphor in which the nation state is represented as a human body.

I have also shown how phraseology containing these four key function words reflects the political history of the period. For example, the pronoun we displays preferences in grammatical aspect depending on whether the referent of we is the party of government or the party of opposition ( we have + past participle is favoured by incumbent parties to indicate what has been achieved in the past). The modal verbs selected by we are also sensitive to this distinction (we would occurs more frequently in the Liberal manifestos – the party with the least experience of government in the period 1945–2010, while we will + continue is particularly favoured by the Conservatives – the party with the most experience and perhaps, therefore, the highest expectations about continuing in power). In addition to reflecting a party's relationship to power, changes in the manifesto genre are also captured in key function words. For example, increase over time in the frequency of we will reflects the development of the manifesto from the written text of an electoral address given by a party leader to a full and detailed policy document setting out a party's plans for government; a development also accompanied by an increase over time of exclusive our + nouns such as policies, plans, programme.

I began this article by suggesting that the claim that function words were of limited interest in discourse analysis – critical or otherwise – was worth questioning, and it seems to me that what has been uncovered here does indeed indicate that a re-evaluation of attitudes towards these often overlooked but fascinating lexical items is now needed.

Aman, Idris (2009): "Discourse and striving for power. An analysis of Barisan nasional's 2004 Malaysian general election manifesto". Discourse and Society 20/8: 659–684.

Baker, Paul (2009): "Issues arising when teaching corpus-assisted (critical) discourse analysis". In: Lombardo, Linda (ed.): Using corpora to learn about language and discourse. Bern, Peter Lang: 73–98.

Baker, Paul (2010): Sociolinguistics and corpus linguistics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Baker, Paul et al. (2008): "A useful methodological synergy? Combining critical discourse analysis and corpus linguistics to examine discourses of refugees and asylum seekers in the UK press". Discourse and Society 19/8: 273–306.

Biber, Douglas et al. (1999): Longman grammar of spoken and written English. London: Longman.

Biber, Douglas/Conrad, Susan/Leech, Geoffrey (2002): Longman student grammar of spoken and written English. London: Longman.

Budge, Ian (1999): "Party policy and ideology. Reversing the 1950s". In: Evans, Geoffrey/Norris, Pippa (eds.): Critical elections. British parties and voters in long-term perspective. London, Sage: 1–21.

Chaney, Paul (2013): "Unfulfilled mandate? Exploring the electoral discourse of international development aid in UK Westminster elections 1945–2010". European Journal of Development Research 25/2: 252–270.

Charteris-Black, Jonathan (2006): "Britain as a container. Immigration metaphors in the 2005 election campaign". Discourse and Society 17/5: 563–581.

Dale, Ian (ed.) (2000a): Conservative party general election manifestos, 1900–1997. London: Routledge.

Dale, Ian (ed.) (2000b): Labour party general election manifestos, 1900–1997. London: Routledge.

Dale, Ian (ed.) (2000c): Liberal party general election manifestos, 1900–1997. London: Routledge.

Edwards, Geraint O. (2012): "A comparative discourse analysis of the construction of 'in-groups' in the 2005 and 2010 manifestos of the British National party". Discourse and Society 23/3: 245–258.

Fairclough, Norman (1992): Discourse and social change. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Groom, Nicholas (2010): "Closed-class keywords and corpus-driven discourse analysis". In Bondi, Marina/Scott, Mike (eds.): Keyness in texts. Amsterdam, John Benjamins: 59–78.

Hoey, Michael (2005): Lexical priming. A new theory of words and language. London: Routledge.

Huber, Evelyne/Stephens, John D. (2005): "State economic and social policy in global capitalism". In: Janoski, Thomas et al. (eds.): The handbook of political sociology. States, civil societies and globalization. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press: 607–629.

Huddleston, Rodney/Pullum, Geoffrey K. (2005): A student's introduction to English grammar. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hunston, Susan/Francis, Gill (2000): Pattern grammar. A corpus-driven approach to the lexical grammar of English. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Kavanagh, Dennis (2000): "Labour party manifestos 1900–1997". In: Dale, Ian (ed): Labour party general election manifestos, 1900– 1997. London, Routledge: 1–8.

Kilgarriff, Adam et al. (2004): "The sketch engine". In: Proceedings of EURALEX 2004, Lorient, France: 105–115. http://www.euralex.org/elx_proceedings/Euralex2004/, accessed March 20, 2014.

Lakoff, George (1993): "The contemporary theory of metaphor". In: Ortony, Andrew (ed.): Metaphor and thought. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press: 202–251.

Mautner, Gerlinde (2010): "Checks and balances. How corpus linguistics can contribute to CDA". In: Wodak, Ruth/Meyer, Michael (eds.): Methods of critical discourse analysis. London, Sage: 122–143.

McCandless, David (2010): Information is beautiful. London: Collins.

McEnery, Tony (2006): Swearing in English. Bad language, purity and power from 1586 to the Present. London: Routledge.

Mulderrig, Jane (2012): "The hegemony of inclusion. A corpus-based critical discourse analysis of deixis in education policy". Discourse and Society 23/6: 701–728.

Newman, John (1996): Give. A cognitive linguistic study. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Noël, Alain/Thérien, Jean-Philippe (2008): Left and right in global politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

O'Halloran, Kieran (2010): "How to use corpus linguistics in the study of media discourse". In: O'Keeffe, Anne/McCarthy, Michael (eds.): The Routledge handbook of corpus linguistics. Abingdon: Routledge: 563–576.

Oxford University Press (ed.): "manifesto, n.". OED Online. December 2012. Oxford University Press.

http://www.oed.com/view/Entry/113499?rskey=QsvOHI&result=1&is

Advanced=false

, accessed March 04, 2013.

Pearce, Michael (2004): "The marketization of discourse about education in UK general election manifestos". TEXT 24/2: 245–265.

Pearce, Michael (2005): "Informalization in UK party election broadcasts 1966–1997". Language and Literature 14/1: 65–90.

Rayson, Paul (2008): "From key words to key semantic domains". International Journal of Corpus Linguistics 13/4: 519–549.

Scott, Mike (2008): WordSmith Tools Version 5. Liverpool: Lexical Analysis Software Ltd.

Scott, Mike (2010): WordSmith tools help manual. Version 5.0. Liverpool: Lexical Analysis Software Ltd.

Scott, Mike/Tribble, Christopher (2006): Textual patterns. Key words and corpus analysis in language education. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Sinclair, John M. (1991): Corpus, concordance, collocation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sinclair, John M. (2004): Trust the text. Language, corpus and discourse. London: Routledge.

Stubbs, Michael (2001): Words and phrases. Corpus studies of lexical semantics. Oxford: Blackwell.

Volpi, Frederic (2006): "Politics". In: Turner, Bryan S. (ed.): The Cambridge dictionary of sociology. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press: 445–447.

Wendt, Alexander (2004): "The state as person in international theory". Review of International Studies 30/2: 289–316.

Weninger, Csilla (2010): "The lexico-grammar of partnerships. Corpus patterns of 'facilitated agency". Text and Talk 30/5: 591–613.

Wodak, Ruth/Meyer, Michael (eds.) (22010): Methods of Critical Discourse Analysis. London: Sage.

Williams, Raymond (1976): Keywords. A vocabulary of culture and society. London: Croom Helm.

1 The corpus was compiled from two sources. For manifestos from the period 1945–2010, I used the electronic versions at Richard Kimber's Political Science Resources website (www.politicsresources.net/area/uk/man.htm). The earlier documents were scanned from Iain Dale's three volume collection of British election manifestos (Dale 2000a, 2000b, 2000c). The Conservative sub-corpus consists of 248, 356 words; Labour's is 235, 327 words and the Liberal sub-corpus is 184, 374 words. back

2 Throughout this article, Liberal and Liberal Party is used generically to refer to the third party of British mainstream politics. Between 1900 and 1979, this party fought every election as 'The Liberal Party', but in the 1980s it entered into an alliance with the Social Democratic Party (which had been formed in 1981) and contested the elections of 1983 and 1987 as the SDP-Liberal Alliance. In 1988 the Liberal Party and the SDP merged to form the Liberal Democrats. After the general election of 2010, the Liberal Democrats entered into a coalition government with the Conservatives. back

3 WordSmith can be found at www.lexically.net/wordsmith/. The Sketch Engine site is at www.sketchengine.co.uk. back

4 The term co-occurrence is used in this article to cover both collocation (the tendency for certain lexical words to occur in the vicinity of a target word/phrase) and colligation (the tendency for certain grammatical words/structural patterns to occur in the vicinity of a target word/phrase). back

5 The picture for we will is somewhat complicated by the presence of an alternative: we shall. In (written) British English, they are semantically equivalent, although we shall is perhaps "somewhat formal and old-fashioned" (Biber/Conrad/Leech 2002: 182). However, it does not appear to be the case that the earlier manifestos are employing we shall as an alternative to we will, since we shall occurs only thirty-five times in the thirty-three manifestos produced between 1900 and 1935. back