)

)

http://dx.doi.org/10.13092/lo.70.1744

Research on English as a lingua franca (ELF), or, more generally, English as a global language (EGL), has been gaining more and more attraction over the past years. Apart from EGL, we also find other synonyms, which I refrain from listing here, though. The terms are not used unanimously in the literature (cf., e.g., Mortensen 2013 on this issue). In some studies, for instance, ELF conversations are defined as including at least one non-native participant, in other studies they are defined as including only non-native participants. I use ELF in the former sense. I very consciously include native speakers in my use of ELF (as a function) and EGL (as a system). In my view, analysing and teaching English as a global language does not make sense if it excludes the native speakers of the globe. Whatever the precise definition in the literature, they always somehow include the use of English by non-native speakers. A number of valuable analyses has been published on this issue. Important corpora have been and are still being collected. Three observations and desiderata can be formulated on ELF/EGL research:

There is no room in this article to summarize all results that pragmatic and other linguistic studies on ELF have offered. This article predominantly aims at showing that in order to teach the pragmatics of English as a global language a variety of methods is fruitful. The single sections could also have been published as separate articles. However, putting the sections together is necessary to show two things: (1) Different analyzing techniques should not be seen as rivalling schools, but as supplementary, cooperative approaches. (2) Pragmalinguistic analyses do not have to end with stating empirical results, but can easily be transferred into educational components if there is an adequately flexible teaching concept. The article will therefore firstly put focus on how pragmalinguistic aspects—here: conversational strategies within certain given scripts and word-connotations (as a topic at the edge of pragmatics and semantics)—can be analyzed by combining both qualitative and quantitative analyses of both naturally and artificially produced data. Secondly, it will offer a concept for concrete implementations of ELF/EGL research results in teaching EGL.

Basic ethnographic methods that can be used in ELF/EGL research already go back to Hall (1959, 1963, 1976) and Hymes (1964, 1972a, 1972b). One way to analyze the use of English by non-natives in lingua-franca situations is noting down particularities in natural conversations, either immediately when a noteworthy form is overheard or while analyzing a prior recording. The latter technique was employed by Jennifer Jenkins, who was the first to give ELF a more in-depth treatment. Analyses are also possible thanks to the corpora that exist today, the following of which are among the larger ones (not all of them are generally accessible, though):

These corpora can also be used to address pragmalinguistic questions—to a larger extent than they have been used for that so far. Corpus analyses have let to the definition of a set of linguistic features that should be respected in intercultural conversations in order to avoid unintelligibility (e.g. Jenkins 2003, Seidlhofer 2007 and the state-of-the-art article by Jenkins/Cogo/Dewey 2011). This "lingua franca core" includes phonological, morphological and syntactic features. Some morphosyntactic observations, though, have pragmalinguistic implications, for instance the structure of interrogatives. Interrogatives should be clearly marked, either by using the standard English word-order or by choosing the word-order of declaratives with a raising intonation at the end (own observations, but see also, e.g., Björkmann 2008). However, it could be underlined, in a concept for teaching ELF/EGL, that the second option, the intonation question, produces sentences with a larger interpretability of the underlying illocutionary force when it does not include an interrogative pronoun or determiner. Depending on the context, such an interrogative may be interpreted as an expressive ('I can't believe it.'), maybe included with a directive ('Is this really so?') or it may be interpreted as a true information question. This can be demonstrated by the following passage from VOICE (line V.LEcon8.144-148).

| (1) | 1 Person 1: You can use your school ID? |

| 2 Person 2: No, it's not the school ID, but this international ID card. | |

| 3 Person 1: Yeah, but I, I have, I have the ISIC also. But you can use your school ID? |

In addition, I collected English interviews from lingua-franca constellations that were available on YouTube in December 2010. This shall be referred to as YELF (YouTube English as a Lingua Franca Corpus). The corpus consists of 19 clips, showing 19 interviewers and 23 interviewees, amounting to 86 minutes. The interviews are from the worlds of sports, entertainment, business and politics. They show 19 different types of intercultural constellations. As can be expected, there are many unproblematic deviations from native standard grammar and pragmatic features that may not be considered natural by native speakers. An analysis of YELF (in which I was partly supported by my student Tobias Radl) yields that there is no evident breakdown that could be attributed to phonetic aspects. But there is one interesting breakdown in a conversation between the Brazilian sportsman Cristiano Ronaldo and a Croatian interviewer, in which Ronaldo does not understand the interviewer's question: Do you sometimes do you wish for more freedom?. This could either be due to the grammatical deviation from standard English or due to the too low volume of the second (and unusual) do you. Pragmatically interesting is the strategy to get out of this situation. (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ELkk0-qOFn8, time 1:21, accessed April 15, 2015):

| (2) | 01 Interviewer: Do you sometimes do you wish for more freedom. (voice going down) |

| 02 Ronaldo: (putting his head slightly more into the interviewer's direction) Say again! | |

| 03 Ronaldo: (smiling) Sorry! (NOT Sorry?) | |

| 04 Interviewer: Hgh (embarrassed laugh). You're deaf. | |

| 05 Both: laughing (4 sec.). | |

| 06 Ronaldo: More freedom? | |

| 07 Interviewer: Yes. | |

| 08 Interviewer: So that you can go free around with some girls to walk free | |

| 09 Interviewer: that nobody follows you. | |

| 10 Interviewer: Do you wish for that. |

Ronaldo, for whatever reason, does not understand, asks the interviewer to repeat the question and apologizes. Despite the apology, the interviewer feels embarrassed and tries to put the blame—even if humorously—on Ronaldo. Both laugh and then Ronaldo finds a solution by repeating the last phrase of the question, thus enhancing a reformulation, or explanation, on the interviewer's side (who may have a different concept of freedom or, possibly, free-time).

In another YELF clip, a Russian woman interviews an Arab female fashion designer. In order to avoid face-threatening situations she uses a pre-empting strategy, namely remarks on a meta-level, raising the awareness of cultural differences, before the actual question. Here is the first instance ( http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7pvw8VW3mwY, time 0'26, accessed April 15, 2015, lines with the same number indicate that the utterances occurred simultaneously, capitalization symbolises emphasized pronunciation, a colon indicates lengthening):

| (3) | 01 Interviewer: I will ask you a VE:RY stupid question. |

| 02 Interviewee: nods | |

| 02 Interviewer: And please don't get upset | |

| 03 Interviewer: because we're really, | |

| 04 Interviewee: Not at all (shaking head, smiling). | |

| 05 Interviewee: Absolute- (laughing) | |

| 06 Interviewee: -ly. (laughing) | |

| 06 Interviewer: Tell me | |

| 07 Interviewer: if the females in Arabic Emerates | |

| 08 Interviewee: Yup. (smiling, looking attentively) | |

| 09 Interviewer: are always wearing black veil | |

| 10 Interviewer: <unintelligible>, | |

| 10 Interviewee: nods | |

| 11 Interviewer: why do they need fashion for? | |

| 11 Interviewee: nods with a few laughs | |

| 12 Interviewee: laughs | |

| 12 Interviewer: Can you tell us exactly <unintelligible>? |

Then the interviewee gives her explanation in a fully friendly way, without no sign of negative feeling or stress. The second "cultural awareness raiser", or "meta-cultural remark", occurs at minute 3:39:

| (4) | 01 Interviewer: And a couple of questions like for a woman, |

| 02 Interviewer: yah? | |

| 02 Interviewee: nods | |

| 03 Interviewee: Yah. | |

| 04 Interviewer: Because we are so diffe-. | |

| 05 Interviewer: -rent. | |

| 05 Interviewee: Yes yes. (with a big smile, almost a laugh) |

Here, we have already entered the realm of pragmatics. As already said, comprehensive pragmatic results on lingua-franca communication in English are fewer then for other aspects. Mention may be made of Juliane House's contributions (e.g. 1999, 2009, 2010), the book by Cogo and Dewey (2012) as well as Meierkord's landmark study from 1996, which is an analysis of naturally occurring conversations among exchange students. Meierkord's study is still frequently quoted and includes the following major results.

Apart from the corpora already cited, another source for pragmalinguistic analyses on English as a lingua franca is the English Wikipedia. It offers a tremendously large corpus of natural productions by native and non-native speakers alike on the pages that are not article pages, where standard English is obligatory. The dialogic interaction is not face-to-face and not immediate, so that it represents a genre of communication that has received considerably less attention in research than face-to-face communication.

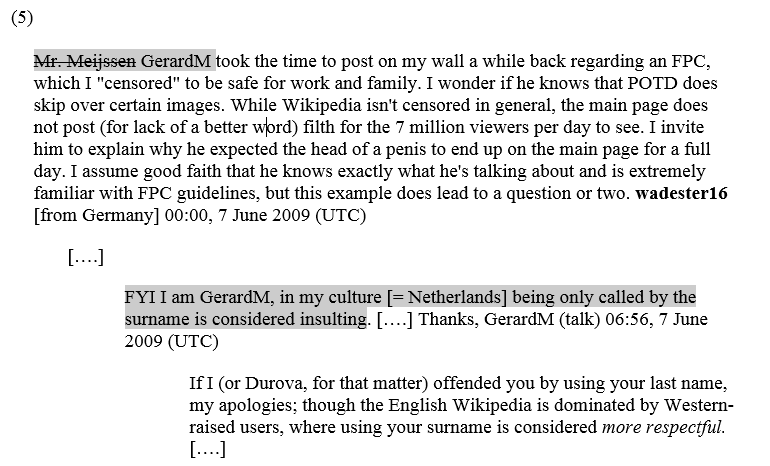

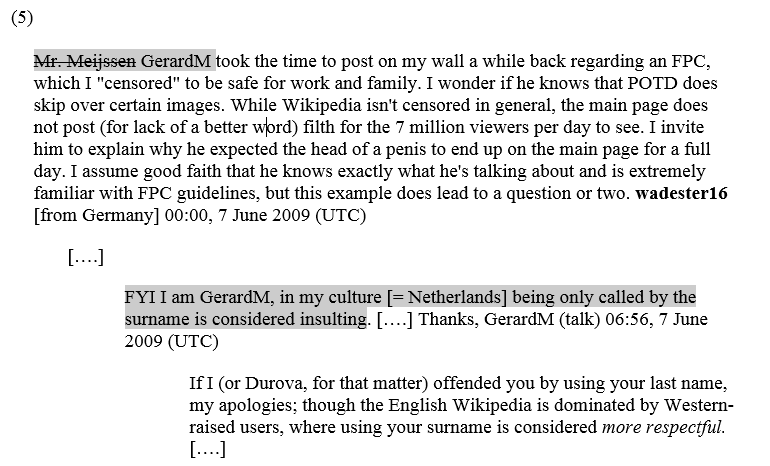

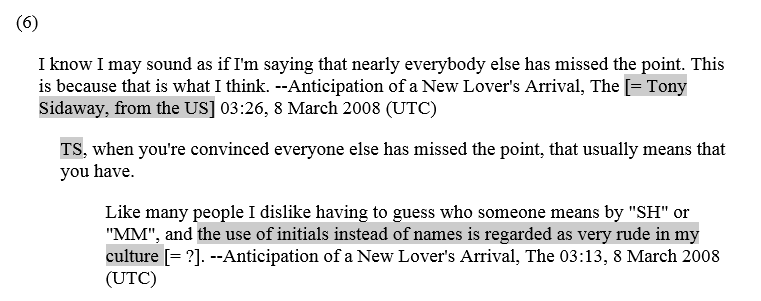

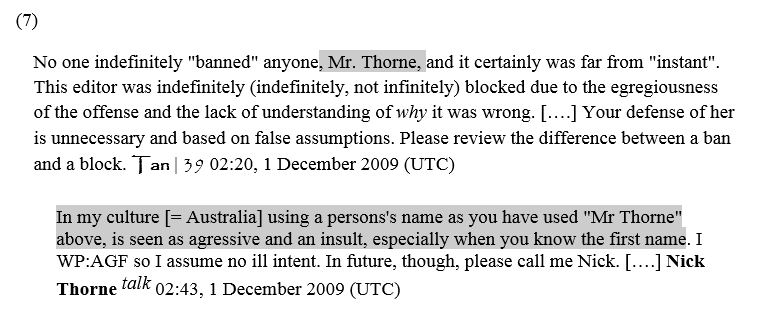

Again, analyzing such naturally occurring written dialogs is possible, but it takes a lot of time to find comparable data and to find enough data to decide whether a certain communicative discomfort is due to, in Jenny Thomas's (1983) terminology, a sociopragmatic failure or a pragmalinguistic failure or still something else. Let us have a look at the following examples of inappropriate or unexpected addressing strategies and the reactions to them. In the following quotations, I have highlighted some passages in gray and added remarks in square brackets. The rest of the layout (underlining, coloring, boldprinting, crossing) has been kept from the original.

)

)

How can we interpret the communicative discomforts in these exchanges? Does the uncommon choice of address terms lead to offence? Or does the uncommon choice of address terms lead to offence in face-threatening acts only, such as corrections and other forms of criticisms? Or does the uncommon choice of address terms serve as the motivation for a counter-attack? This is hard to find out by collecting exclusively natural data. Pragmatic aspects are so much tied to invisible, cognitive aspects and they rely so much more on the extra-linguistic context—suffice it to quote some basic literature on speech-acts, communicative competence, conversational maxims and politeness theory here: Austin (1962), Searle (1969, 1976), Bateson (1972), Hymes (1964, 1972a, 1972b), Grice (1975), Brown/Levinson (e.g. 1987), Goffman (1955, 1967), Leech (1983). In pragmalinguistic studies, it seems particularly adequate to gather data by artifically eliciting text-production, but: on potentially naturally occurring situations.

Frequent and widely accepted techniques for gathering data for speech-act analysis, which was first used in a cross-cultural project on request and apologies (Blum-Kulka/House/Kasper 1989) are

I have already commented on these techniques elsewhere (Grzega/Schöner 2008, Grzega 2013: 29–32). Suffice it to say here that all three techniques only elicit the first or most typical answer that comes to an informant's mind, but not the whole spectrum of answers that an informant may possibly resort to. This could result in wrong deductions about culture-specificity. DCTs allow only for a tentative classification of strategies that will occur in natural speech and a picture of stereotypical perceptions. These caveats led to the development of meta-linguistic judgement tests (MJT), or meta-pragmatic judgement tests, as already suggested by Olshtain/Blum-Kulka (1984) or in alternative ways by Chen (1996) and Hinkel (1997). An MJT typically unveils the most frequent types of utterances gathered in a prior DCT or DCQ and asks informants to rank the appropriateness of the utterances. A certain weakness of this test is indeed that informants can evaluate merely a restricted amount of linguistic forms. Also of note, a number of studies has shown that informants' introspections of their frequent or typical sometimes misrepresent their actual use of words (cf., e.g., Labov 1966, Blom/Gumperz 1972, Grzega 1997: 166). Demonstrably, this even applies to trained linguists (cf. Brouwer/Gerritsen/deHaan 1979: 47). This appears to hold predominantly true when informants have to create spoken language in a written medium, resulting, inter alia, in unnatural reductions of repetition, negotiation, hedging, elaboration, utterance length, and variation (cf. Beebe 1985: 3 and 11). So, MJTs, too, enable but provisional classifications and a sense for stereotypical perceptions of language use. Of course, it is not denied that these are already valuable achievements.

In my own project, the first step was to have international students participate in a DPT on a non-face-threatening act, namely an e-mail asking for a reservation of a hotel room, which can be considered a situation that a lot of people put themselves into today. It is, again, a non-face-to-face non-synchronous dialog situation. The instruction read this:

You want to spend your Christmas vacation in [X-city] together with a friend. You have chosen an inexpensive hotel that also offers rooms without breakfast. Write to the e-mail indicated above and make a reservation for such a double room at this hotel.

All informants were given the text in their mother tongues in order to avoid prompting any standard English words or phrases. For the further steps of the project I only took into account countries for which I had at least 7 informants: Germany (28), Italy (13), France (9), Spain (9), the US (9). The US informants were particularly interesting to compare native and non-native use. The question was: will these e-mails be communicatively successful? Do they meet readers' expectations of politeness? Of course, the question may be raised: Why should politeness be relevant in such a genre? Based on informal interviews, I assume that hotels, too, are more willing to cooperate with customers whom they do not perceive as "difficult".

For this, some sort of assessment test was required. I decided to create a metapragmatic judgement task (MJT) for a non-face-to-face non-synchronous situation.

You are temporarily working for a hotel in your home region. On its website the hotel offers different types of rooms and even gives the choice between stays with breakfast and stays without breakfast. Your specific job at the hotel is to answer all kinds of e-mails from all over the world. Most of the e-mails are reservations. Sometimes e-mails appear rather polite, sometimes overpolite, sometimes impolite. In the following questionnaire, your first task is to evaluate different phrases for the single parts of such e-mails (salutation, preliminary remark, actual reservation, closing formula). In the second part, you will be asked about how you view specific sentences from actual e-mails. Please answer rather quickly as we want to get your first impression.

Since the texts to be analyzed consisted of various elements where politeness could be violated, I decided to split the script "e-mailed hotel reservation" into 7 slots (based on the e-mails I had received).

Then I collected each country's most prominent type(s) of form for each slot as well as some forms that do not occur among the US informants at all. As in a classical MJT, I asked informants—who were different from those that participated in the DPT—to classify each form as "very appropriate", "rather appropriate", "rather inappropriate" or "very inappropriate". But to make sure that the MJT informants associate appropriateness with politeness and not with spelling or grammar, spelling and grammar errors were levelled out (In contrast, the second part of this MJT—see below—complete or large parts of e-mails presented exactly the way they were handed, i.e. with spelling, grammar and vocabulary errors).

As of yet, the MJT was completed by

We will first take a look at the salutation and valediction formulae. The tables show the figures for the British informants, the American informants, the group of informants that are non-native speakers of English, and in particular the figures for the nations just mentioned. The figures are not the arithmetic means, but the median of the answers on the scale "very appropriate" (1), "rather appropriate" (2), "rather inappropriate" (3), "very inappropriate" (4). The median is the numerical value separating the higher half of informant answers from the lower half of informant answers.

(1) Salutation

|

Formulation |

US |

UK |

NNS |

DE |

FR |

IT |

FI |

PL |

HU |

RU |

|

|

a. Dear Sir or Madam |

DE |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

b. Dear Sir/Madam |

IT |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

|

c. Dear ladies and gentlemen |

*US |

3 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

1 |

|

d. Hello |

US, ES |

2 |

2 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

|

e. Good morning |

FR |

2 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

2 |

|

f. --- |

ES |

3 |

3 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

3 |

4 |

4 |

3 |

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

(6) Closing formula

|

Formulation |

US |

UK |

NNS |

DE |

FR |

IT |

FI |

PL |

HU |

RU |

|

|

a. Yours faithfully, |

*US |

3 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

b. Sincerely yours, |

DE |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

|

c. Best regards, |

IT |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

|

d. Kind regards, |

IT |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

|

e. Thank you. Kind regards, |

IT |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

|

f. Thank you. Sincerely yours, |

DE |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

|

g. Thank you. |

US |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

|

h. --- |

FR, US |

3 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

3 |

4 |

4 |

3 |

What can we observe? In many learner dictionaries (e.g. CIDE, DCE, OALD) we find that Dear Sir or Madam should be used as an opening formula in formal letters (the OALD also mentions To whom it may concern for American English, but this was not used by any of the American informants in this text-type). The interesting results for this first slot are the following.

All in all, the mass of non-native speakers seems to be trapped in a certain "complex-is-polite principle". Let us now have a look at the closing formulae. In many dictionaries (CIDE 815, DCE 978f., OALD R53) we find strict distinctions between different forms of valediction. The rule given is: When you don't know the addressee's name, you close the letter with Yours faithfully in Britain and Yours truly or Sincerely (yours) in the US; in Britain, Yours sincerely is used only when you know the addressee's name. In the textbook New Highlight 4, Unit 5, only Yours faithfully is given. The reality in my project is this:

This leads us to the conclusion that native speakers perceive hotel reservation e-mails rather as relatives of informal letters than as relatives of formal letters. In sum, the actual use and acceptance of forms is not as strict as textbooks and dictionaries make us believe ("learner-book illusion").

Let us now look at, and comment on, the other slots.

(2) Preliminary remark

|

Formulation |

US |

UK |

NNS |

DE |

FR |

IT |

FI |

PL |

HU |

RU |

|

|

a. I am writing you in order to make a reservation. |

*US |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

|

b. My name is Mikael Agricola. (= introduction of name) |

IT, (DE, ES), *US |

2 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

2 |

|

c. --- |

all |

3 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

3 |

4 |

3 |

4 |

4 |

3 |

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

On the quoted pages, the dictionaries also suggest using a phrase that could be seen as an illocutionary-force indicating device (IFID), i.e. an expression that explicitly says what the illocutionary force is. The term was coined by Searle (1969). None of the American informants actually used it in their mail ("learner-book illusion"), but the Americans as well as all other country informants consider such a phrase appropriate. Some non-native speakers introduced their name, which is considered inappropriate only by the German group.

(3) Booking request

|

Formulation |

US |

UK |

NNS |

DE |

FR |

IT |

FI |

PL |

HU |

RU |

|

|

a. I would like to book a double room without breakfast ...(= neutral style) |

DE, ES, IT, FR |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

|

b. I would like to reserve a double room without breakfast ... (= educated style) |

US |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

|

c. I would like to make a reservation for a double room without breakfast ... (= legalese-like style) |

DE |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

d. Is it possible to book a double room without breakfast... (= interrogatory). |

(ES) |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

In this selection of phrases, I wanted to connect style and sentence type with politeness. There were no noteworthy country differences. All four variants were considered rather or even very appropriate.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

(4) Date

|

Formulation |

US |

UK |

NNS |

DE |

FR |

IT |

FI |

PL |

HU |

RU |

|

|

a. ... from 07.08.09 to 09.08.09 |

*US |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

|

b. ... from 08/07/09 to 08/09/09 |

all |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

|

c. ... from August 7 to August 9 |

all |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Here, an international style-book such as Weiss (2005) advises the international sender to write out the month to avoid any misunderstandings triggered by the culturally varying order of day and month. Both native speaker groups consider the use of the month's name most appropriate, but the other patterns are also not inappropriate. The non-native groups, consider all patterns appropriate, but on deeper levels the picture of the non-native speakers is very mixed.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

(5) Booking confirmation

|

Formulation |

US |

UK |

NNS |

DE |

FR |

IT |

FI |

PL |

HU |

RU |

|

|

a. Please confirm my booking __. |

FR |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

|

b. Please confirm my booking as soon as possible. |

DE |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

|

c. I would be grateful if you would confirm my booking as soon as possible. |

DE, IT, *US |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

d. --- |

IT, US |

3 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

4 |

3 |

4 |

4 |

3 |

(The answers of ES were very mixed so that there is no strategy that is used by at least half of the Spanish informants.)

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

On the average, all groups agree that the use of the would construction is very appropriate— although none of the native DPT informants used it—, but that the more direct constructions are still appropriate (except the French informants who evaluate the first entry as inappropriate).

The second part of the project consisted of randomly selected twelve DCTs which were quoted in part or in full exactly the way they were written. This time the classical MJT label appropriate was avoided to exclude that informants' view is predominantly on grammatical elements. Instead, the label polite was used; however, it should be realized that polite is not the end-pole of a "polite—impolite" scale. Rather, it seems the ideally balanced point on an "impolite—overpolite" scale. Overpoliteness was included because it may give the impression of insincerity and thus be as irritating as impoliteness. The MJT informants were then to decide whether each message presented to them was "unclear, "clear, but impolite", "clear and polite", "clear, but overpolite". Of course, the answer "clear" only shows that for the reader there was a clear message. Whether it is the one that the writer intended was not checked. From the results of the older studies summarized above and the first part of this study, the following hypotheses can be tested:

(1) MPJT informants coming from the same country as the DPT informants will categorize an e-mail as "unclear" not more frequently than those coming from other countries. (This is based on the observation that interferences which occur on the phonetic, morphosyntactic and lexical levels are more easily decodable by speakers of the same mother-tongue.)

(2) MPJT informants coming from the same country as the DPT informants will categorize an e-mail as "polite" as much as all countries taken together. (This is based on Meierkord's observation that on the pragmatic level interferences from the native culture are rare.)

(3) Non-native MPJT informants categorize an e-mail more often as "polite" than native informants (This is based on the observed "let-it-pass principle" by non-native speakers).

(4) As can be inferred from the first part of the questionnaire, the choice of the salutation and the valediction will not play a central role.

The figures in the following table are percentages. The names in the original messages have been altered; everything else was kept. If more than a quarter of a country's informants thinks that the e-mail is unclear or impolite, the figure is set in boldface. If more than half of a country's informants categorize an e-mail the same way, the figure is set in boldface and italics.

|

DE-1 |

Dear sir/madam, I would like to book a double room from 15/08 to 17/08. I would like to inform you that we will abstain from eating any kind of food at the hotel. |

|||

|

unclear |

clear, but impolite |

clear and polite |

clear, but overpolite |

|

|

UK |

6 |

56 |

28 |

11 |

|

US |

11 |

40 |

24 |

24 |

|

NNS |

3 |

49 |

30 |

19 |

|

DE |

2 |

60 |

17 |

21 |

|

FR |

6 |

53 |

29 |

12 |

|

IT |

0 |

29 |

29 |

43 |

|

FI |

0 |

75 |

17 |

8 |

|

PL |

3 |

29 |

49 |

0 |

|

HU |

0 |

4 |

67 |

22 |

|

RU |

0 |

57 |

29 |

14 |

|

all |

4 |

48 |

30 |

19 |

|

DE-2 |

Hello, I'm interested to book a double room for 5 days stating the night form 20 to 21 December. My dates: Name: Olaf Jansson, Address: .... |

|||

|

unclear |

clear, but impolite |

clear and polite |

clear, but overpolite |

|

|

UK |

29 |

0 |

71 |

0 |

|

US |

54 |

9 |

37 |

0 |

|

NNS |

20 |

36 |

44 |

0 |

|

DE |

15 |

37 |

48 |

0 |

|

FR |

31 |

44 |

19 |

6 |

|

IT |

71 |

14 |

14 |

0 |

|

FI |

33 |

25 |

42 |

0 |

|

PL |

16 |

42 |

42 |

0 |

|

HU |

0 |

61 |

33 |

0 |

|

RU |

0 |

43 |

57 |

0 |

|

all |

26 |

30 |

44 |

0 |

|

DE-3 |

Hello, I want to book a double bedroom over the period from August 23 to September 7 2009 without breakfast. |

|||

|

unclear |

clear, but impolite |

clear and polite |

clear, but overpolite |

|

|

UK |

6 |

12 |

82 |

0 |

|

US |

0 |

36 |

64 |

0 |

|

NNS |

5 |

55 |

38 |

2 |

|

DE |

3 |

65 |

31 |

1 |

|

FR |

6 |

65 |

30 |

0 |

|

IT |

14 |

57 |

29 |

0 |

|

FI |

8 |

50 |

42 |

0 |

|

PL |

8 |

47 |

41 |

4 |

|

HU |

0 |

78 |

22 |

0 |

|

RU |

0 |

43 |

57 |

0 |

|

all |

4 |

51 |

44 |

1 |

|

DE-4 |

Hello, I would like to book a double room for Mr. Jan Olafsson. Arriving at 26 Dezember, leaving 2 January. I require a room excluding brakefast. Regards, Jan Olafsson. |

|||

|

unclear |

clear, but impolite |

clear and polite |

clear, but overpolite |

|

|

UK |

0 |

18 |

82 |

0 |

|

US |

9 |

27 |

64 |

0 |

|

NNS |

4 |

36 |

56 |

4 |

|

DE |

2 |

37 |

58 |

2 |

|

FR |

6 |

35 |

59 |

0 |

|

IT |

0 |

57 |

43 |

0 |

|

FI |

0 |

17 |

83 |

0 |

|

PL |

10 |

38 |

44 |

7 |

|

HU |

0 |

44 |

44 |

11 |

|

RU |

0 |

43 |

57 |

0 |

|

all |

5 |

33 |

59 |

3 |

|

FR-1 |

Hello, I want to spend my holidays in your city. My first question will concerne the fact that I'm student and I want to know if you cann offer me some attractive price. .... |

|||

|

unclear |

clear, but impolite |

clear and polite |

clear, but overpolite |

|

|

UK |

28 |

28 |

44 |

0 |

|

US |

13 |

47 |

36 |

4 |

|

NNS |

15 |

54 |

30 |

2 |

|

DE |

13 |

65 |

22 |

0 |

|

FR |

29 |

47 |

24 |

0 |

|

IT |

0 |

71 |

29 |

0 |

|

FI |

17 |

17 |

50 |

17 |

|

PL |

19 |

35 |

30 |

17 |

|

HU |

22 |

67 |

11 |

0 |

|

RU |

14 |

86 |

0 |

0 |

|

all |

16 |

52 |

30 |

2 |

|

FR-2 |

Hello, I would like to book a chamber for 2 persons without breakfasts. Do you have a vacancy room from the 23rd to the 26 of august? .... |

|||

|

unclear |

clear, but impolite |

clear and polite |

clear, but overpolite |

|

|

UK |

6 |

11 |

78 |

6 |

|

US |

4 |

13 |

76 |

7 |

|

NNS |

16 |

28 |

52 |

4 |

|

DE |

16 |

27 |

56 |

2 |

|

FR |

35 |

24 |

41 |

0 |

|

IT |

29 |

14 |

57 |

0 |

|

FI |

0 |

8 |

92 |

0 |

|

PL |

17 |

38 |

38 |

8 |

|

HU |

22 |

33 |

44 |

0 |

|

RU |

14 |

43 |

29 |

14 |

|

all |

13 |

25 |

58 |

5 |

|

FR-3 |

Hello. I would like to book a double room for Aug 7 to Aug 10. It would be great if you could answer us within a fortnight. Regards, P. Moto. |

|||

|

unclear |

clear, but impolite |

clear and polite |

clear, but overpolite |

|

|

UK |

0 |

22 |

78 |

0 |

|

US |

11 |

30 |

55 |

5 |

|

NNS |

5 |

29 |

62 |

4 |

|

DE |

6 |

32 |

61 |

2 |

|

FR |

6 |

29 |

65 |

0 |

|

IT |

0 |

29 |

57 |

14 |

|

FI |

8 |

0 |

92 |

0 |

|

PL |

4 |

34 |

56 |

7 |

|

HU |

11 |

56 |

33 |

0 |

|

RU |

14 |

14 |

71 |

0 |

|

all |

6 |

30 |

61 |

4 |

|

FR-4 |

Dear madam/sir - Have you a room with double bed or two simple bed available for a week at this date: 25-27 August? Regards, T. Kim |

|||

|

unclear |

clear, but impolite |

clear and polite |

clear, but overpolite |

|

|

UK |

28 |

6 |

67 |

0 |

|

US |

28 |

7 |

56 |

10 |

|

NNS |

20 |

30 |

48 |

3 |

|

DE |

25 |

28 |

47 |

1 |

|

FR |

24 |

12 |

65 |

0 |

|

IT |

14 |

0 |

71 |

14 |

|

FI |

25 |

8 |

58 |

8 |

|

PL |

8 |

47 |

42 |

4 |

|

HU |

33 |

33 |

33 |

0 |

|

RU |

17 |

67 |

17 |

ß |

|

all |

21 |

24 |

51 |

4 |

|

IT-1 |

Hello, I'm intentioned to spend my holidays in your city by a friend of mine. Therefore, I want to reserve a room for us from August 10 to August 12. Thank you, R. Ibrahim |

|||

|

unclear |

clear, but impolite |

clear and polite |

clear, but overpolite |

|

|

UK |

44 |

17 |

39 |

0 |

|

US |

44 |

9 |

38 |

9 |

|

NNS |

32 |

22 |

33 |

14 |

|

DE |

35 |

16 |

39 |

10 |

|

FR |

53 |

12 |

29 |

6 |

|

IT |

29 |

29 |

14 |

29 |

|

FI |

42 |

17 |

42 |

0 |

|

PL |

19 |

35 |

29 |

17 |

|

HU |

33 |

22 |

33 |

11 |

|

RU |

29 |

0 |

43 |

29 |

|

all |

34 |

19 |

36 |

11 |

|

IT-2 |

Dear madam/sir - I would like a room for the night from August 7 to August 9 inclusive. Kind regards, K. Habib |

|||

|

unclear |

clear, but impolite |

clear and polite |

clear, but overpolite |

|

|

UK |

22 |

11 |

67 |

0 |

|

US |

37 |

9 |

50 |

2 |

|

NNS |

26 |

24 |

49 |

2 |

|

DE |

35 |

29 |

36 |

0 |

|

FR |

24 |

24 |

53 |

0 |

|

IT |

14 |

29 |

57 |

0 |

|

FI |

42 |

8 |

50 |

0 |

|

PL |

18 |

24 |

55 |

4 |

|

HU |

22 |

22 |

56 |

0 |

|

RU |

29 |

29 |

43 |

0 |

|

all |

27 |

21 |

51 |

2 |

|

US-1 |

I would like to reserve a room for two people from Aug 7 to Aug 10. We would like two beds or at least one queen size bed if two beds are not available. We would like just the room and do not wish to utilize your hotel's breakfast option. |

|||

|

unclear |

clear, but impolite |

clear and polite |

clear, but overpolite |

|

|

UK |

6 |

11 |

61 |

22 |

|

US |

0 |

7 |

82 |

11 |

|

NNS |

5 |

33 |

48 |

15 |

|

DE |

4 |

35 |

45 |

17 |

|

FR |

18 |

30 |

47 |

0 |

|

IT |

0 |

71 |

29 |

0 |

|

FI |

0 |

8 |

75 |

17 |

|

PL |

5 |

40 |

36 |

18 |

|

HU |

0 |

33 |

56 |

11 |

|

RU |

0 |

43 |

43 |

14 |

|

all |

4 |

28 |

54 |

15 |

|

US-2 |

Hello - Do you have any vacancies for this coming weekend? I would like to book a double room for two people - no breakfast required. Regards, T. Rajid |

|||

|

unclear |

clear, but impolite |

clear and polite |

clear, but overpolite |

|

|

UK |

17 |

0 |

83 |

0 |

|

US |

9 |

7 |

84 |

0 |

|

NNS |

16 |

25 |

58 |

1 |

|

DE |

13 |

21 |

65 |

2 |

|

FR |

6 |

13 |

81 |

0 |

|

IT |

0 |

0 |

100 |

0 |

|

FI |

25 |

8 |

67 |

0 |

|

PL |

20 |

34 |

44 |

1 |

|

HU |

0 |

78 |

22 |

0 |

|

RU |

29 |

43 |

29 |

0 |

|

all |

14 |

22 |

63 |

1 |

How can we analyze and interpret the data? The following observations and conclusions can be drawn:

1. Hypothesis #1—MPJT informants coming from the same country as the DPT informants will categorize an e-mail as "unclear" not more frequently than those coming from other countries—could be verified for most, but not all e-mails. Noteworthy cases are these:

The following table indicates which e-mails were considered unclear by more than 25% of the informants of a group:

|

DE-1 |

DE-2 |

DE-3 |

DE-4 |

FR-1 |

FR-2 |

FR-3 |

FR-4 |

IT-1 |

IT-2 |

US-1 |

US-2 |

|

|

UK |

x |

x |

x |

x |

||||||||

|

US |

x |

x |

x |

x |

||||||||

|

NNS |

x |

x |

||||||||||

|

DE |

x |

x |

||||||||||

|

FR |

x |

x |

x |

x |

||||||||

|

IT |

x |

x |

x |

|||||||||

|

FI |

x |

x |

x |

|||||||||

|

PL |

||||||||||||

|

HU |

x |

x |

||||||||||

|

RU |

x |

x |

x |

|||||||||

|

all |

x |

x |

x |

The e-mails that most informants had problems with were IT-1, IT-2 and DE-2. DE-2 contains two typos that may cause confusion because they lead to different existing words and may thus cause unclear reference: "... book a double room for 5 days stating the night form 20 to 21 December". The reader may see 5 days on the one hand and 20 to 21 December (which is 2 days or one night) on the other and wonder for which period the guest would like to stay exactly. This confusion may even be enforced by the next brick, which says My dates: Name: Olaf Jansson. The writer probably mixed up data and date. The way it is presented now (with two colons) the reader could think that the date is missing and that the writer continued with his name.The length of the stay is also unclear in IT-2: the missing plural marker in "the night from August 7 to August 9 inclusive" may lead to confusion. The addressee may wonder where the mistake is: should it be nights or August 8? In IT-1 the wrong preposition in "I'm intentioned to spend my holidays in your city by a friend of mine" may lead to confusion, particularly in connection with the request for "a room for us".

2. Hypothesis #2—MPJT informants coming from the same country as the DPT informants categorize an e-mail as "polite" as much as all countries taken together—is not generally supported by our results. For DE-1, DE-3, FR-2 and IT-1, the number of fellow countrypersons who consider the respective e-mail as polite is quite low in comparison with the number of informants from other countries. In contrast, for FR-4, US-1 and US-2, the number of fellow countrypersons who labeled the respective e-mail "polite" is quite high in comparison with the number of informants from other countries.

3. Hypothesis #3—non-native MPJT informants will categorize an e-mail more often as "polite" than native informants—could not be verified. The British informants consistently label an e-mail "polite" as often as the non-native group does. In some cases they do this even very clearly (DE-3, FR-2). Similarly, the Americans do not label an e-mail "polite" significantly less frequently than the non-native speaker group who shows the lowest percentage value for any of the e-mails selected. In other words: The British adhere to the "let-it-pass" principle more than non-native speakers, and Americans adhere to it not less than non-native speakers.

4. Also of note, though, the average Finn does not categorize a single e-mail as "clear and polite" to a significantly lower percentage than any other average country informant. This means that sometimes the French, sometimes the Italians, sometimes the Germans are most resistent in regarding a message as "polite", but never the Finns. One reason for this may be that according to Hofstede's (2000) study Finland is the only one of these countries that ranks in the lower half of the uncertainty avoidance scale, which means that Finnish culture is characterized rather by tolerance and openness to innovation than by conservatism. However, more studies (and more informants) are required for any definitive judgements.

5. If we take into account the answers of all informants, US-2 was most frequently (63%) and DE-1 and FR-1 least frequently (30%) labeled "clear and polite". A ranking of the e-mails most frequently classified as "clear and polite" for the country informant groups looks like this:

|

DE-1 |

DE-2 |

DE-3 |

DE-4 |

FR-1 |

FR-2 |

FR-3 |

FR-4 |

IT-1 |

IT-2 |

US-1 |

US-2 |

|

|

UK |

2 |

2 |

1 |

|||||||||

|

US |

3 |

2 |

1 |

|||||||||

|

NNS |

3 |

1 |

2 |

|||||||||

|

DE |

3 |

2 |

1 |

|||||||||

|

FR |

2 |

2 |

1 |

|||||||||

|

IT |

3 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

||||||||

|

FI |

3 |

1 |

1 |

|||||||||

|

PL |

(3)* |

1 |

2 |

|||||||||

|

HU |

1 |

2 |

2 |

|||||||||

|

RU |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

||||||||

|

all |

3 |

2 |

1 |

* = below 50%

The following table indicates which mails were considered "clear, but impolite" by at least 25% of the informants of a group; if more than half of the country informants considered the mail impolite, this is indicated by "xx":

|

DE-1 |

DE-2 |

DE-3 |

DE-4 |

FR-1 |

FR-2 |

FR-3 |

FR-4 |

IT-1 |

IT-2 |

US-1 |

US-2 |

|

|

UK |

xx |

x |

||||||||||

|

US |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

|||||||

|

NNS |

x |

x |

xx |

x |

xx |

x |

x |

x |

x |

|||

|

DE |

xx |

x |

xx |

x |

xx |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

||

|

FR |

xx |

x |

xx |

x |

x |

x |

x |

|||||

|

IT |

x |

xx |

xx |

xx |

x |

x |

x |

xx |

||||

|

FI |

xx |

x |

x |

|||||||||

|

PL |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

x |

|

|

HU |

xx |

xx |

x |

xx |

x |

xx |

x |

x |

xx |

|||

|

RU |

xx |

x |

x |

x |

xx |

x |

xx |

x |

x |

x |

||

|

all |

x |

x |

xx |

x |

xx |

x |

x |

What do the e-mails among the top three polite mails at least in one country have in common? What do the e-mails considered impolite by a large part of the informants have in common? First, it should be emphasized that Hypothesis #4 could be verified: the salutation form did not play a central role in the readers' judgement. Second, in all e-mails seen as polite the request for a hotel reservation is formulated with I would like or as an interrogatory. This does not mean, though, that I would like is enough for an e-mail to be automatically seen as polite by the average reader. But the e-mails that include I want do rank among those that are predominantly seen as "impolite": DE-3 and FR-1. Apart from these two, DE-1 and DE-4 are also considered "impolite" by a large portion of the informants (excluding the British). DE-1's evaluation may have to do with the formulation "... we will abstain from eating any kind of food at the hotel", which may make the reader think that the sender has already had, or heard of, bad experiences with the hotel food—it may even sound like a threat. DE-4 is a remarkable case because, according to the judgement of all informants taken together, it ranks both among the Top 3 polite e-mails and among the e-mails that more than 25 percent consider impolite. This may be explainable by the fact that, on the one hand, the e-mail includes the expression I would like, but, on the other hand, also the very demanding expression I require; in addition, the sender writes about himself in the third person singular ("... book a double room for Mr. Jan Olafsson") and uses telegraphic style in his second sentence ("Arriving at 26 Dezember, leaving 2 January"). Similarly, FR-3 is among the Top 3, but was regarded as impolite by a considerable number of countries. This may be due to the fact that the writer used the sophisticated expression fortnight, but also kept his letter very brief. Furthermore, it seems that the e-mails that contain telegraphic elements (DE-2, DE-4, US-2) are considered impolite especially by Russians, Poles, and Hungarians.

6. The two e-mails that received the highest evaluations for the label "overpolite" are DE-1 (19%) and US-1 (15%). All others are below 10%. What those two have in common is the use of sophisticated words (DE-1 abstain, US-1 utilize); however, other e-mails also include elaborate terms without being considered overpolite: FR-2 chambre (probably due to Fr. chambre 'bedroom'), FR-3 fortnight, IT-1 I'm intentioned to... (not even lexicalized, probably due to It. sono intenzionato a...). Whether a larger natural corpus could help us to find out about the effects of waffling is unclear, since there are so many other aspects and slots that may vary.

An additional note: Unfortunately, there were not enough instances to comment on the influence of overdoing explicitness (cf. Seidlhofer 2004), that is the use of unusually explicit constructions (e.g. FR-4 "for a week at this date: 25–27 August" instead of "from 25 to 27 August"), or, more generally, the waffle phenomenon (cf. Blum-Kulka/Olshtain 1986), that is a learner's oversupply of politeness markers, downgraders and longer constructions (DE-1 "I would like to inform you that we will abstain from eating any kind of food" and FR-1 "My first question will concerne the fact that I'm student and I want to know if you...").

In a second study, I have dealt with a face-threatening act. Again, I have first created a DPT for a realistic face-threatening situation in a non-synchronous, written context. As mentioned before, a highly frequented venue of Internet communication is eBay, so the following DPT was created:

At eBay you have a DVD from an X vendor. The internet description classified the quality of the video as "good". However, when you watch the video, the sound contains a lot of hissing noise. Complain to the vendor about this.

In the actual questionnaire, X was replaced by Italian for German informants and by German for informants from other countries. All informants received the text in their mother tongues so that no direction could prompt any standard English words or phrases. Several dozens of texts were produced by informants from a broad range of countries. For the further steps, only countries for which more than 5 texts could be collected were respected: Germany (15), Spain (9), France (7), the US (7). As the communicative success can only be measured through an assessment test, a metapragmatic judgment task had to be created next. The MJT accepted those 3 e-mails per country that turned out to be most typical of each country with regard to

Among the discourse markers that researchers have described as typical for ELF (cf., e.g., House 2010: 376ff.), only so was relevant for this type of script (cf. e-mails DE-3, FR-2, ES-1).

The MJT informants—which were not the same as the DPT informants—had to imagine themselves in the position of the vendor:

You frequently sell things on eBay.com to people from all over the world. For a friend you've now sold (under the name vendor123) several copies of a special edition of the Disney film "Bambi" on eBay. The following days you receive these 12 e-mails. Read the e-mails and say whether you regard them appropriate or not, that is: whether you as a seller feel treated fairly or unfairly.

They then had to decide whether they considered an e-mail by the customer "very fair", "rather fair", "rather unfair", "very unfair" or whether they "can't tell because they don't quite understand the text". Why should fair treatment be linked to communicative success? Trading is successful if customers' needs for fair treatment are fulfilled, i.e. if they get a good DVD or their money as quickly as possible. My assumption is that a customer's complaint, too, will be successful if it is not face-threatening to the vendor. Fair treatment of the vendor will lead to faster service for the customer. In retrospect, the customer will then experience whether the e-mail complaint was communicatively efficient, or successful.

As of yet, the MJT was filled out by

In the tables, the second line gives the percentages of informants who did not quite understand the e-mail. The figures of each first line are the median of answers on the scale "very fair" (3), "rather fair" (2), "rather unfair" (1), "very unfair" (0). The last column shows the Total Politeness Index: the sum of all national medians.

|

US-1

Good morning,

|

|||||||||||

|

UK |

US |

NNS |

DE |

FR |

IT |

FI |

PL |

HU |

RU |

Tot.PI |

|

|

fairness |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

26 |

|

unintelligible (%) |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

|

|

US-2

Hi,

|

|||||||||||

|

UK |

US |

NNS |

DE |

FR |

IT |

FI |

PL |

HU |

RU |

Tot.PI |

|

|

fairness |

3 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

2.5 |

2 |

22.5 |

|

unintelligible (%) |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

9 |

6 |

0 |

0 |

|

|

US-3

Dear vendor123,

|

|||||||||||

|

UK |

US |

NNS |

DE |

FR |

IT |

FI |

PL |

HU |

RU |

Tot.PI |

|

|

fairness |

3 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

2 |

24 |

|

unintelligible (%) |

0 |

0 |

5 |

4 |

0 |

9 |

0 |

9 |

0 |

0 |

|

|

DE-1

Dear Sir or Madam,

|

|||||||||||

|

UK |

US |

NNS |

DE |

FR |

IT |

FI |

PL |

HU |

RU |

Tot.PI |

|

|

fairness |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

3 |

21 |

|

unintelligible (%) |

0 |

0 |

3 |

2 |

7 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

0 |

0 |

|

|

DE-2

Dear Sir or Madam,

|

|||||||||||

|

UK |

US |

NNS |

DE |

FR |

IT |

FI |

PL |

HU |

RU |

Tot.PI |

|

|

fairness |

2 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

25 |

|

unintelligible (%) |

7 |

0 |

3 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

5 |

0 |

14 |

|

|

DE-3

Hello,

|

|||||||||||

|

UK |

US |

NNS |

DE |

FR |

IT |

FI |

PL |

HU |

RU |

Tot.PI |

|

|

fairness |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

18 |

|

unintelligible (%) |

7 |

7 |

5 |

2 |

0 |

9 |

9 |

8 |

0 |

13 |

|

|

FR-1

Dear mister,

|

|||||||||||

|

UK |

US |

NNS |

DE |

FR |

IT |

FI |

PL |

HU |

RU |

Tot.PO |

|

|

fairness |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2.5 |

2 |

1 |

1.5 |

1 |

16 |

|

unintelligible (%) |

33 |

23 |

19 |

16 |

20 |

22 |

37 |

22 |

0 |

13 |

|

|

FR-2

Good morning,

|

|||||||||||

|

UK |

US |

NNS |

DE |

FR |

IT |

FI |

PL |

HU |

RU |

Tot.PI |

|

|

fairness |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

18 |

|

unintelligible (%) |

7 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

|

|

FR-3

Hello. I ordered a DVD two weeks ago through your online-store on Ebay. On the item description, it was written that the quality of the

video was good. Unfortunately it is not the case and the sound has a really poor quality. I would like you to replace it or to refund the

money I paid. Thanks.

|

|||||||||||

|

UK |

US |

NNS |

DE |

FR |

IT |

FI |

PL |

HU |

RU |

Tot.PI |

|

|

fairness |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

11 |

|

unintelligible (%) |

13 |

9 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

5 |

0 |

0 |

|

&nbps;

|

ES-1

Hello

|

|||||||||||

|

UK |

US |

NNS |

DE |

FR |

IT |

FI |

PL |

HU |

RU |

Tot.PI |

|

|

fairness |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2.5 |

2 |

18.5 |

|

unintelligible (%) |

0 |

0 |

4 |

3 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

6 |

0 |

29 |

|

<

|

ES-2

Dear vendor123,

|

|||||||||||

|

UK |

US |

NNS |

DE |

FR |

IT |

FI |

PL |

HU |

RU |

Tot.PI |

|

|

fairness |

2.5 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2.5 |

1 |

19 |

|

unintelligible (%) |

13 |

9 |

7 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

9 |

11 |

0 |

13 |

|

|

ES-3

Dear Mr,

|

|||||||||||

|

UK |

US |

NNS |

DE |

FR |

IT |

FI |

PL |

HU |

RU |

Tot.PI |

|

|

fairness |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1.5 |

2 |

2 |

1.5 |

1.5 |

16.5 |

|

unintelligible (%) |

0 |

0 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

10 |

5 |

0 |

0 |

|

The ranks according to the Total Politeness Index are these:

|

Rank |

|

Tot.PI |

violations against StE |

|

1 |

US-1 |

26 |

0 |

|

2 |

DE-2 |

25 |

4 |

|

3 |

US-3 |

24 |

0 |

|

4 |

US-2 |

22.5 |

0 |

|

5 |

DE-1 |

21 |

1 |

|

6 |

ES-2 |

19 |

5 |

|

7 |

ES-1 |

18.5 |

5 |

|

8 |

FR-2 |

18 |

6 |

|

8 |

DE-3 |

18 |

5 |

|

10 |

ES-3 |

16.5 |

1 |

|

11 |

FR-1 |

16 |

10 |

|

12 |

FR-3 |

11 |

0 |

Furthermore, in order to get to know more about informants' motives for the "fair—unfair" rating, I did not use one line for open comments (as did Chen [1996] in her MJTs), but I provided informants with a list of answers and added a line "Other". Here is a simplified illustration of the percentages of informants that ticked a parameter influencing their "fairness" ratings (in contrast to Grzega 2013, the informants that did not tick at least one item in this last part of the questionnaire were not counted although they have completely filled out the rest, i.e. 100% = informants who did fill out at least something in this part of the questionnaire; if two thirds of all countries pass the 33%-level, the strategy is in boldprint, if two thirds of all countries pass the 67%-level, the strategy is in bold-print and underlined):

|

100%≥x≥ 67% |

67%>x≥ 33% |

33%>x>0% |

|

|

(A) The author used a proper form of address and greeting. |

PL |

UK, DE, FR, IT |

US, FI, HU, RU |

|

(B) The author used a proper form of closing the e-mail. |

UK, FR, IT, PL, HU, RU |

US, DE, FI |

|

|

(C) The author explained in detail what was the problem with the DVD. |

US, UK, DE, FI, IT, PL |

FR, HU, RU |

|

|

(D) The author formulated rather a wish than an order. |

UK, DE, FR, FI, IT, PL |

US, HU, RU |

|

|

(E) The author did not attack me personally. |

US, UK, DE, FR, FI, IT |

PL, HU, RU |

|

|

(F) The author mentioned also good aspects of our deal. |

FR, FI, IT |

US, UK, DE, PL, HU, RU |

|

|

(G) The author said exactly what s/he wants. |

UK |

US, DE, FR, FI, PL, HU, RU |

IT |

|

(H) The author named more than one solution for handling the situation. |

US, UK, DE, FR, FI |

IT, PL, HU, RU |

|

|

(I) The author gave me a choice for how to handle the situation. |

US, DE, FI, IT, RU |

UK, FR, PL, HU |

|

|

(J) The author showed his emotions. |

US, UK, DE, FR, FI, IT, PL, HU, RU |

||

|

(K) The e-mail was written in good English. |

US, UK, FI, IT, PL, RU |

DE, FR, HU |

Beschriftung

(The answers under the point "Other" were very individual and did not offer any interesting aspects. For classificaitons related to European use vs. non-European use, cf. Grzega 2013: 128f.)

How can we analyze and interpret the data? Based on all these data, we can test the following 7 hypotheses on the "fair–unfair" rating, working with two statistical tests, namely the t-test and the chi-square test (cf. Cochran 1954).

|

#1a. |

MJT informants rate e-mails with the use of Dear + sir/madam or the username (vendor123) higher than other opening forms ( Hello, Good morning, Dear mister). (This is based on prior ethnographic observations.) |

True, except for US-1 [Hello] and US-2 [Hi]). However, this result is not statistically significant (t=1.8818, df=9, p=0.0926 for group1≠group2, and p=0.9537 for group1>group2). |

|

#1b. |

MJT informants rate e-mails with the use of either Hello or Dear + sir/madam or the username (vendor123) higher than other opening forms (Hello, Good morning, Dear mister). (This is based on the first meta-pragmatic judgement task.) |

Not true. But the results are not statistically significant (t=-0.1153, df=9, p=0.9108 for group1≠group2, and p=0.5449 for group1>group2). |

|

#2. |

Mails with violations against Standard English grammar are not rated lower than mails without violations as long as they are intelligible (= not more than 10% informants judging a mail as unintelligible). ("let-pass principle" observation.) |

True, as the differences are negligible (r=-0.29; r²=0.09). |

|

#3. |

(Obs.: Pragmatic interference is rare:) MJT informants coming from the same country as the DPT informants rate an e-mail not higher than those coming from other countries. |

True for FR and DE. Not true for US-2 (t=4.081, df=80, p=0.0001) US-3 (t=3.8514, df=92, p=0.0001) |

|

#4a. |

(Based on the "let-it-pass principle" observed for non-native speakers:) Non-native MJT informants rank an e-mail not lower than British informants. |

Not true: Not corroborated for FR-1 (t=-1.9583, df=11, p=0.0383) US-2 (t=-2.5088, df=18, p=0.0110) US-3 (t=-2.9263, df=20, p=0.0042) ES-3 (t=-2.0539, df=18, p=0.0274) FR-2 (t=-2.3272, df=21, p=0.0150) |

|

#4b |

(Based on the "let-it-pass principle" observed for non-native speakers:) Non-native MJT informants rate an e-mail not lower than American informants. |

Not true: Not corroborated for FR-1 (t=-2.5395, df=50, p=0.0071) US-1 (t=-5.0921, df=128, p<0.0001) US-2 (t=-4.3243, df=80, p<0.0001) US-3 (t=-3.9728, df=92, p=0.0001) ES-1 (t=-3.8740, df=73, p=0.0001) ES-3 (t=-3.4144, df=80, p=0.0005) FR-2 (t=-2.9422, df=68, p=0.0022) |

|

#5. |

The respected non-native speakers attach less value to the forms of address, greeting and valediction and the use of standard English grammar than the British and American informants. (This is based on the "let-it-pass principle" observed for non-native speakers.) |

Not true. (Not corroborated for any single item by chi-square tests.) |

|

#6. |

There are discourse strategies that are more important for (a) British, (b) American informants than address, greeting, valediction or the use of standard English grammar. (This is based on prior ethnographic observations.) |

(According to chi-square tests:) True for American informants, namely for E. Not true for British informants. |

|

#7. |

There are discourse strategies that are more important for the respected non-native speakers than address, greeting, valediction and the use of standard English grammar. (This is based on prior ethnographic observations.) |

(According to chi-square tests:) True, namely for D and C. |

(For hypotheses related to European use vs. non-European use, cf. Grzega 2013: 128f.).

In sum, many hypotheses that have suggested themselves from prior observations on naturally occurring data could not be verified by the experimental data.

As criticism against discourse creation and multiple-choice judgement tasks was also raised by others (cf., e.g., Geluykens 2007: 35f.) and as the goal of cross-cultural comparisons is often a more general and abstract one, the technique of a semi-expert interview on communication strategies (SICS) was proposed as an additional technique. The technique (cf. Grzega/Schöner 2008, Grzega 2013: 31f.) is to discover all acceptable utterances as well as their degrees of acceptability and their connotations in specific situations. A SICS can be envisaged as a supplement to traditional ethnographic techniques. The SICS is distributed to persons who deal with language professionally and can therefore be expected to be distinctly sensitive to communicative behavior. They are thus conceived as ethnological semi-experts giving their introspective view of the typical communicative behavior in their speech groups, picturing themselves in the role of someone who explains this to a foreigner. Informants are asked to note down both adequate and inadequate communicative patterns in a given situation. A SICS works with lists of communicative patterns to be chosen from as well as space for adding unprefabricated patterns and further useful information.

Production and judgement tests as well as semi-expert interviews work best for scripts with few and brief slots. The more prominent a scenario, the more readily useful the results will be for the EGL learner. However, there are also conversational themes that allow a larger number and variety of slots, in other words: very individual ways of talking, where (prefabricated) patterns do not play an important role. This does not mean that misunderstandings that fall in the realm of pragmalinguistics are excluded. As already said, an area at the edge of semantics and pragmatics is the use of single words with regard to what is beyond the denotational meaning. It would be very unusual if word-connotations were the only language components where non-natives automatically followed native usage. Example 3 in Section 2.1, for instance, suggests that the word fashion triggers different notions in the interviewer's and the interviewee's mind. In Example 2 such connotative differences may rest in the word freedom (or free-time, which the interviewer might have meant). But are the connotatives differences individual or culture-bound? This can only be found out with more informants.

Generally, cross-cultural studies on connotative similarities and differences of words are not very numerous. One reason may be that it is not easy to collect and classify data on cultural differences in a non-cultural way. If informants simply have to give their first associations with certain words, difficulties arise when the answers have to be grouped. Alternatively, Wierzbicka (e.g. 1997) has used a list of semantic primes to describe denotative and connotative aspects of meaning. She has specifically dealt with lexemes for friendship, freedom and fatherland in Australia, Russia, Poland, Germany, and Japan. In the 1950's, Charles E. Osgood and his team created the technique of the semantic differential. With this technique, informants are shown words together with a number of 7-step scales of bipolar antonyms. Informants then have to assign a position on each 7-step scale to a given word. The arithmetic means of informant answers express the group connotations of a word. The bipolar antonyms are not necessarily categories that the concept is typically connected with. Osgood and his colleagues rather wanted to detect anthropologically universal principles of structuring the world. From their—also cross-cultural—studies, they concluded that the three universal categories are evaluation (good—bad), potency (strong—weak), and activity (active—passive) (cf. Osgood/Suci 1955, Osgood/Suci/Tannenbaum 1957, Osgood 1964). According to Kumata/Schramm (1956), there are merely two dimensions: the evaluative dimension (good—bad) and the dynamism dimension (strong/active—weak/passive). Gulliksen (1958: 94) suggested to refine semantic differentials by enlarging the 7-step scales to 15-step or even 25-step scales. For the pragmalinguist, though, context-free characterization is particularly interesting when it is more general, not fine-tuned, as then the characteristic feature is also likely to be present in many concrete contexts. In order to find out such basic features, it even seems sufficient to have just 4 steps on scales (strongly +X, rather +X, rather –X, strongly –X). Instead of adjectival pairs that represent universal dimensions of structuring the world, another approach are words for universal needs, a long-term topic in anthropology. It can then be studied to what degree a word is closely linked with a certain need or the satisfaction of a certain need. A model of universal needs that are presented in scalar way is the one by Martin (1994). Departing from the famous need pyramid by Maslow (1943), Martin thinks that human beings constantly try to discover the best way to control conflicting needs, in particular chaos—order, simplicity—complexity, integration—differentiation, freedom—restrictions, emotion—reason, egotism—altruism, individuality—community. The latter pair reminds us of one of the basic classificatory principles in cross-cultural anthropology (e.g. Hofstede 2000). It is also possible to work with one-dimensional scales, as did Wolf/Polzenhagen (2006). One-dimensional lists of allegedly universal needs that could then be resorted to are offered by Maslow, Max-Neef (1986, 1991), and Rosenberg 2003, 2005). Still another approach would be to present a short story, a situation, to informants, connect it to a term and then ask for a reaction, e.g. "In this situation, if you called X a friend, would you expect rather A, B or C from him?" This is a technique that Trompenaars/Hampden-Turner (1997) have used—however, not in connection with lingua-franca issues.

For this study, informants were asked "to connect the words to the elements of the oppositions: this means [...] to say, e.g., whether [they] associate, e.g., the word democracy 'strongly with good', 'rather with good', 'rather with bad', or 'strongly with bad'". They were presented grids of English words (no matter whether native or non-native speaker) that looked like this.

|

strongly with good |

rather with good |

rather with bad |

strongly with bad |

|

|

I associate EUROPE ... |

||||

|

I associate DEMOCRACY ... |

||||

|

I associate ARTS ... |

||||

|

I associate FREE-TIME... |

||||

|

I associate THE PRESS... |

||||

|

I associate SCHOOL ... |

||||

|

I associate THE STATE... |

||||

|

I associate TAXES... |

||||

|

I associate WEALTH... |

||||

|

I associate WORK... |

The set of associations were the classical Osgood scales good/bad, strong/weak, active/passive and the central anthropological scale individuality/community. The selected words are derived from topics that different student groups said to have experienced as probable topics once you went beyond pure small talk with people from other countries.

By February 2013, the semantic differential was completed by

If we calculate the median, i.e. the numerical value separating the higher half of the data sample from the lower half (with 1 = 'strongly with good' ... 4 = 'strongly with bad'), the results are these:

|

Europe |

US |

UK |

AU |

DE |

FR |

IT |

FI |

PL |

HU |

RU |

BR |

|

good/bad |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

|

strong/weak |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

|

active/passive |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

|

individuality/ community |

2 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

|

democracy |

US |

UK |

AU |

DE |

FR |

IT |

FI |

PL |

HU |

RU |

BR |

|

good/bad |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

|

strong/weak |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

|

active/passive |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

|

individuality/ community |

2 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

2 |

3 |

|

arts |

US |

UK |

AU |

DE |

FR |

IT |

FI |

PL |

HU |

RU |

BR |

|

good/bad |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

1 |

|

strong/weak |

2 |

2 |

2 |

3 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

|

active/passive |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

|

individuality/ community |

1 |

2 |

1 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

1 |

|

free-time |

US |

UK |

AU |

DE |

FR |

IT |

FI |

PL |

HU |

RU |

BR |

|