http://dx.doi.org/10.13092/lo.70.1746

Language experts have made consistent attempts at various times to identify some of the specific features that characterize the Nigerian English variety through what could be termed "documentary linguistics" (see Elugbe 2006). This study is one of such attempts. The work intends to contribute, at least in a modest way, to the description of some unique features of what has been described by various scholars as "Educated Spoken Nigerian English" (see Eka 1985, 2000; Odumuh 1987).

Several historical records have accounted for the development of the English language since its arrival in Nigeria about two centuries ago (Adetugbo 1978; Jibril 1982; Eka 2000; Bamgbose 1995; Banjo 1996; Ike 2001; Hunjo 2002). Such records attest to the fact that the English language, having remained on the Nigerian soil for quite a long time, has acquired certain distinctive characteristics that are peculiarly Nigerian. This last point serves as the motivation for this study. The present research is an investigation into patterns of juxtapositional assimilation in Nigerian Spoken English. The intention is to identify and describe patterns of assimilatory processes peculiar to Nigerian spoken English and that could in the long run facilitate its intelligibility and aid further identification of the variety.

Generally, when sounds occur in close contact, either at word boundary in connected speech, or at syllable juncture within lexical items, a new sound segment, which may be an amalgam of the sounds in contact, do emerge following an affinity of such sounds (Dinneen 1966: 12). Intra-word sound changes (e.g. /ŋ/ in concrete /kɑŋkriːt/) are mostly considered from a diachronic perspective, but some also owe their explanations to specific instances in synchronic sound change. However, what is significant is that all kinds of phonological modifications resulting from the influence of one sound segment on the neighbouring or adjacent segment are explicable in terms of juxtapositional assimilation.

In Standard British English (SBE), several scholars have observed that casual, rapid or colloquial expressions are characterized by considerable amount of phonemic variations among speakers, either within a word, or at word boundaries, or at syllable or morpheme boundaries, among others (Gimson/Cruttenden 1994; Chomsky/Halle 1968; Yule 1996; Shariatmadari 2006). At other times, such variations occur as a result of "different choice of internal phonemes depending on the assimilatory pressure of the word environment felt by the speaker", or the phonological environment within which a phoneme occurs (Gimson/Cruttenden 1994: 257). However, Abercrombie (1967) classifies three kinds of phenomena as assimilation: historical assimilation, juxtapositional assimilation and similitude. He further sub-classifies juxtapositional assimilatory processes as comprising progressive (also known as preseverative assimilation), regressive or anticipatory assimilation and homorganic assimilation. These last three juxtapositional assimilation types are the ones on which the current study concentrates with emphasis on the consonantal transmutation rather than on the vocalic.

A panoply of scholars have made considerable efforts at describing the English language spoken in Nigeria since its inception in about the 16th century, (Brosnahan 1958; Banjo 1971; Jowitt 1991; Gut 2004). But the term "Nigerian English" (NigE) appears to have continued to evoke heated controversies among researchers. Jibril (1986: 51), for instance, views NigE as "a cluster of regional and social varieties which interact sufficiently in a sociolinguistic continuum to qualify for a common cover term". Some scholars such as Jowitt (1991), Hunjo (2002), Udofot (2003), Gut (2004, 2005, 2007), Peng and Ann (2004), Simo Bobda (1995, 2003, 2007, 2010), Soneye (2010), Josiah/Babatunde (2011), Akande (2012) and Josiah (2014) describe, especially, the rhythmic and phonological features of NigE as a unique variety. Ike (2001: 75), on the other hand, dismisses in a rather quixotic reaction, the existence of Nigerian English and remarks that, "The term Nigerian English can […] never be a correct label by which to describe the variety peculiar to Nigerians"; nevertheless, the quantum of available studies on Nigerian English in the 21st century nationally and internationally forcefully asserts its reality. Okoro (2004: 166) corroborates this latter view by stating that "Nigerian English is a recognized variety of English worldwide, and has taken its pride of place among the "New Englishes".

One thing is contextually significant in all the arguments on NigE and it is the fact that, there exists a variety of English language in Nigeria which has acquired certain identifiable characteristics that make it peculiarly distinct from the Standard British English (SBE) and other sub-types of Englishes spoken elsewhere in the world. The English language in the Nigerian society has no lesser role than the expression and conservation of cultural norms and values – it is interwoven with the Nigerian socio-cultural environment and so, it is distinctly Nigerian both in use and usage. This development has given rise to such terminologies like, "Nigerianisms", "acculturation", "domestication", "nativization", "indigenization", among others, which have been variously coined to describe the "Nigerianness" of the English language in the Nigerian environment (Adegbija 2004). From the foregoing, there is no doubt that NigE has found its way into the global linguistic domain as a variety of "World Englishes" both in principle and in practice.

The intention of this research is to employ relevant research approaches to find out patterns of juxtapositional assimilation that are peculiar to Nigerian educated users of English, with a view to increasing the quantum of available data on the features of NigE. The result of such an exercise could generally, further illuminate grey areas in English as a Second Language pedagogy and that of Nigerian English users in particular.

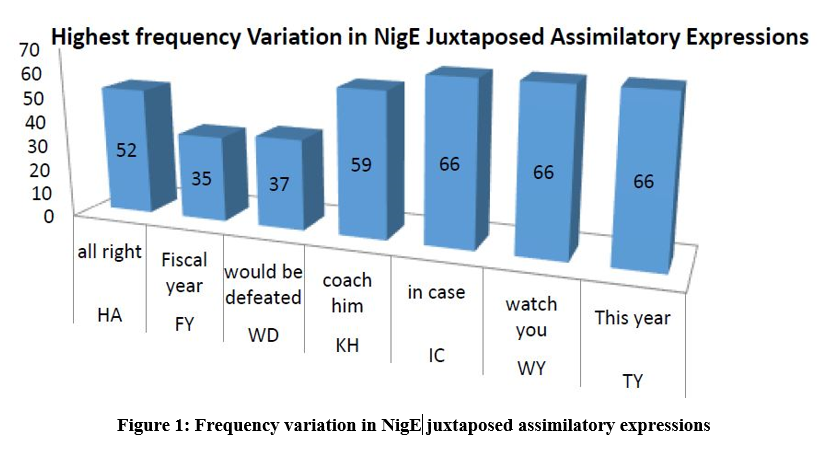

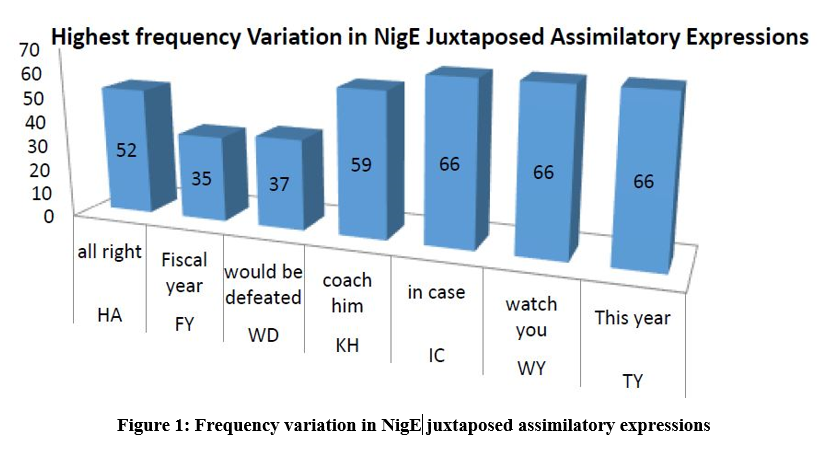

One hundred final year university undergraduates from five Federal government owned universities across Nigeria, twenty from each, read aloud a list of phrase-like words in connected speech. Three of such were to test for progressive assimilation, namely watch you, This Year and c oach him and another three for regressive assimilation namely in case, would be defeated, and fiscal year. Only one was used to test for homorganic assimilation which is All right, (see table 2 for details). A Briton, who is a native speaker of English and a lecturer (of more than 25 years) in one of the Federal government owned universities also read aloud the word list and acts as the control for the one hundred participants. This choice of respondents was to ensure a fair spread to cover, at least minimally, ethnic groups in various parts of the country and make the data fairly representative of the different parts of Nigeria. The various respondents were drawn from nineteen linguistic groups including the three major languages namely Hausa, Yoruba and Igbo. Although, Nigeria has between 400 and 513 identified languages (Grimes 2000; Elugbe 2006) and the few employed in the study may be insufficient for generalization, the specific features identified in their assimilatory processes will make for interesting description and contribution to features of Nigerian English. In all, seven hundred tokens of words in connected speech were annotated and subjected to both manual and instrumental analysis.

Three important aspects of Juxtapositional assimilation are considered in this section, namely: progressive or perseverative assimilation, regressive or anticipatory assimilation and homorganic assimilation. The data presented on Tables 1 and 2 illustrate instances of these assimilatory processes. They are presented in the following order: progressive assimilation regressive assimilation and homorganic assimilation.

|

S/N |

Assimilation Type |

Subjects' Renditions |

Code |

% |

Peculiar assimilatory effects to consonants |

|

Progressive Assimilation |

|||||

|

1. |

w atch you /wɒtʃ ju:/ |

wɔtʃ ʤu: |

WY 3 |

66 |

/ʤ/ instead of /j/ |

|

2. |

this year /ðɪs jɜː/ or /ðɪs jɪə/ |

disie |

TY 3 |

66 |

/i/ instead of /j/ |

|

3. |

c oach him /kəʊtʃ hɪm/ |

kotʃim |

KH 2 |

59 |

deletion of /h/ |

|

Regressive Assimilation |

|||||

|

4. |

i n case /ɪn keɪs/ |

iŋkes |

IC 4 |

66 |

/ŋ/ instead of /n/ |

|

5. |

would be defeated /wʊd bɪ dɪ'fiːted/ |

wʊdbidifɪted [wʊb bi di'fɪted] |

WD 2 (WD3) |

37 (34) |

/d/ coda deleted in would and the onset /b/ in be duplicated |

|

6. |

fiscal year /'fisk(ə)l jɜ:/ |

Fiskal jie [fisika jie] [fisku jie] |

FY3 (FY5) (FY4) |

35 (18) (14) |

About the same number as the highest deleted the coda /l/ in fi s cal |

|

Homorganic Assimilation |

|||||

|

7. |

al l right /'ɔːlraɪt/ |

ɔːrait [wʊbbidi'fɪted] |

HA 1 |

52 |

deletion of /l/ |

Table 1: A summary of the highest significant percentages in progressive, regressive and homorganic assimilatory renditions (WY: watch you; TY:this year; KH: coach him; IC: in case; WD: would be defeated; FY: fiscal year; HA: homorganic assimilation ( all right))

Figure 1: Frequency variation in NigE juxtaposed assimilatory expressions

|

S/N |

Assimilation Type |

Code |

% |

Subject's Rendition |

|

1. |

w atch you /wɒtʃ ju:/ |

WY1 WY2 WY3 WY4 WY5 WY6 WY7 WY8 |

6 7 66 6 2 6 6 1 |

wɒtʃ juː wɔtʃ juː wɔtʃ ʤʊ wɔtʃ ju wɔtʃɑʊt watʃ ʤuː wɔtʃ u: wɔtʃ ʤuː |

|

2. |

this year /ðɪs jɜː/ or /ðɪs jɪə/ |

TY1 TY2 TY3 TY4 TY5 TY6 |

2 3 66 18 9 2 |

ðɪs jɜː dɪs jɜː 'disie 'disia disjie diʃie |

|

3. |

c oach him /kəʊtʃ hɪm/ |

KH1 KH2 KH3 KH4 KH5 |

7 59 9 11 14 |

kəʊtʃ hɪm kotʃim kɒtʃim kɔtʃim koʃim |

|

4. |

in case /ɪn keɪs/ |

IC1 IC2 IC3 IC4 |

10 18 6 66 |

ɪn keɪs iŋ keɪs in kes ɪŋ kes |

|

5. |

would be defeated /wʊd bɪ dɪ'fiːted/ |

WD1 WD2 WD3 WD4 WD5 WD6 |

9 37 34 7 8 5 |

wʊd bɪ di'fɪted wʊd bi di'fɪted wʊb bi di'fɪted wʊ bɪ di'fɪted wil bi di'fɪted wʊd bi di'piːted |

|

6. |

fiscal year /'fisk(ə)l jɜ:/ |

FY1 FY2 FY3 FY4 FY5 FY6 FY7 FY8 FY9 |

2 7 35 14 18 9 1 5 9 |

'fiskl jɜː 'fiska jie 'fiskal jie 'fisku jie 'fisika jie 'pis(i)ka jia 'fiʃal jie 'fiskul jia 'fiskul jie |

|

Homorganic Assimilation |

||||

|

7. |

al l right /'ɔːlraɪt/ |

HA1 HA2 HA3 HA4 HA5 |

52 36 10 1 1 |

'ɔːrait 'ɔːlrait 'ɔrait 'hɔːlrait 'hɔːrait |

Table 2: Details of patterns and percentages in the three tested assimilation types

Different sets of words which occurred on our corpus were used to test progressive assimilation in Nigerian Spoken English. The words in connected speech used as exponents appear in two sets namely: watch you, This Year and coach him. Renditions with the highest number of respondents are shown on table 1, while details of the results and variations in renditions are documented on table 2.

Example 1: watch you /wɒtʃ ju:/

Watch you / wɒtʃ ju:/ is tagged WY 1 to 8 to indicate the categories or variations in renditions. "WY3" represents the most significant realization (see table 1). This means that most of the respondents realized the expression "watch you" / wɒtʃ ju: / as [wɔtʃ ʤu:]. Specifically, 66% of the respondents read aloud "watch you" with the omission of the palatal glide /j/ found in the control's rendition. This was followed by those subjects who realized the "WY2" and "WY4"versions, that is, [wɔtʃu:] and [wɔtʃju] respectively (see table 2). Also, only 6% of the respondents realized the "WY1" variant /wɒtʃ juː/, which is the Standard British English (SBE) variant and corresponds to the form realized by the "Control” as earlier mentioned. Six Hausa speakers were heard articulating the variant [watʃ ʤuː] while five Yoruba and one Anaang speakers were heard articulating the form [wɔʃu]. One Ijaw respondent realized the form [wɔʃʤu] while two other subjects pronounced the variety, watch out [wɔtʃɑʊt]. However, these last two realizations were not statistically significant as recorded in table 2. This item appeared to have been realized by the two respondents in error.

Certain explanations are necessary to provide details on the instance of progressive assimilation in the realization of the items coded "WY2" and "WY3". In "WY2", [wɔtʃu], the process involved is assimilation of place of articulation. This means that the same organ (hard palate) in the palatal region is involved in realizing the two sounds, /tʃ/ and /j/. It could further be described as homorganic assimilation. For instance, the last segment of the first word /tʃ/ is a palato-alveolar affricate and is in contact with the first segment of the following word: "you", that is, /j/ which is a palatal glide. In realizing [wɔtʃu], the palato-alveolar affricate /tʃ/ is phonetically stronger than the glide /j/, therefore, the weaker segment is eliminated giving rise to the phonetic form [wɔtʃu] (cf Shariatmadari 2006). This process can also be described as a case of contact assimilation (Trask 1996) in which two sounds in contact result in the elimination of the sound that precedes it.

Relatively, the WY3 [wɔtʃ ʤu:], which is the most significant form is a case of both palatalization and progressive voicing assimilation (PVA). Here, the two sounds /tʃ/ and /j/ are in contact: the first (i.e. /tʃ/) is a purely fortis consonant and the second, a sonorant (or lenis segment). The contact of the fortis segment /tʃ/ with the lenis glide /j/ results in a new formative at the assimilation site producing the voiced palato-alveolar affricate /ʤ/. However, some of the respondents did not produce the form [wɔtʃ ʤu:], possibly because the sound [ʤ] as observed by Jowitt (1991) and Jibril (1982) are not present in some mother-tongues (MTs) in Nigerian languages such as Efik and Ibibio. Relatively, the voiceless palato-alveolar affricate /tʃ/ is known to be absent in Yoruba, therefore, the voiceless palato-alveolar fricative [ʃ] present in the language was used as a substitute. This is classified as a case of mother-tongue interference.

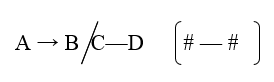

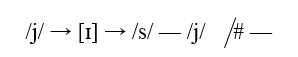

One of the areas of interest in this study is the need to find out why only six (6) out of the one hundred (100) respondents that read the data articulated the SBE variant. This requires our use of Generative Phonology (GP) as a tool to analyze the change that takes place when /tʃ/ is in contact with /j/. Here, we will employ the schema:

![]() This rule is interpreted as: obstruent, i.e. [— Sonorant] (plosives, affricates and fricatives) become voiced in the environment of a voiced obstruent or a

voiced segment, e.g. the glide /j/. From the perspective of the taxonomic model, the rule presented here indicates that the voiceless palato-alveolar

affricate /tʃ/ changes to the voiced palato-alveolar affricate [ʤ] in the environment of the palatal glide /j/. Thus, it could be difficult to realize the

segments /tʃ/ and /j/ in close contact without feature spreading taking place. The feature spreading can take the form of partial or complete assimilation

as in [ʤ], or may even take the form of substitution as in the case of Y2 on table 2. The instance of assimilation noticed here is progressive,

representing the schema /tʃ/ →/j/ [ʤ] # ―. This means that /tʃ/ in contact with /j/ becomes [ʤ] in word initial position.

This rule is interpreted as: obstruent, i.e. [— Sonorant] (plosives, affricates and fricatives) become voiced in the environment of a voiced obstruent or a

voiced segment, e.g. the glide /j/. From the perspective of the taxonomic model, the rule presented here indicates that the voiceless palato-alveolar

affricate /tʃ/ changes to the voiced palato-alveolar affricate [ʤ] in the environment of the palatal glide /j/. Thus, it could be difficult to realize the

segments /tʃ/ and /j/ in close contact without feature spreading taking place. The feature spreading can take the form of partial or complete assimilation

as in [ʤ], or may even take the form of substitution as in the case of Y2 on table 2. The instance of assimilation noticed here is progressive,

representing the schema /tʃ/ →/j/ [ʤ] # ―. This means that /tʃ/ in contact with /j/ becomes [ʤ] in word initial position.

Based on the analysis above, we conclude that the realization of the expression watch you /wɒtʃ ju:/ as [wɔtʃu] or [wɔtʃ ʤu:] has more of phonetic motivation than mother-tongue interference, and could occur among native speakers and non-native speakers alike (cf. Gimson/Cruttenden 1994; Roach 1991). The details of the explanation given here could equally be extended to accommodate expressions such as catch you, would you, did you, and so on, where the assimilating influence maintains forward movement in anticipation of the next place of articulation resulting from copying some features of the preceding segment.

Example 2: this year /ðɪsjɜː/ or /ðɪsjɪə/

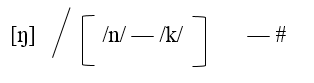

Another expression that occurred on our corpus, which exemplified an instance of progressive assimilation in Nigerian Spoken English, is the phrase, this year. Six variant forms of this expression were extracted from the respondent's performance. One of the least realized variants among the six was the form [ðɪs jɜː] which also exemplified the type articulated by the Control. The Control's realization corresponds to the one obtained in RP. The variant that was realized by most of the respondents is [disie] tagged (TY 3). Generally, it was not surprising to see [ɪ] replacing [j] because, as Trask (1996: 157) has noted, the English glides /j/ and /w/ are brief versions of [ɪ] and [u]. Thus, where /j/ appears close to /ɪ/ in an utterance, one of them, especially the /i/ element usually becomes more pronounced. Thus, the palatal glide /j/ usually gets assimilated to [i] and sometimes becomes completely elided by syncopation. The assimilatory influence moves forward in this case as shown in the following schema:

This is interpreted as /j/ becomes [ɪ] in the environment ( ) of /s/ and /j/ in word initial position (# ―).

We noticed that majority of the subjects representing 66% pronounced the expression this year /ðɪs jɜː/ as ['disie] followed by ['disia] (18%). This means that majority of the respondents substituted the voiced alveolar plosive [d] for the voiced dental fricative /ð/. A second noticeable occurrence (apart from substitution) was that the voiceless alveolar fricative /s/ assimilated to the palatal glide /j/ while the latter was eliminated resulting in the variant [disie]. It would appear slightly difficult to explain why sounds occurring at different points of articulation (in this case, alveolar and palatal regions) become assimilated to the extent that a strident replaces a sonorant. First, this is an instance of progressive assimilation in which the influence of the final segment of the first word [s] moves forward and replaces the next sound /j/ whose place of articulation appears to be farther away. In the case represented here, both /s/ and /i/ are apical segments, and since the tongue has to travel the minimal distance to articulate /j/ which is both palatal and dorsal, it eliminates the distant back consonant /j/ replacing it with /i/ which is phonetically similar. Again, as Trask (1996: 157) has noted, (just as we commented earlier), the English glides /j/ and /w/ are brief versions of /i/ and /u/. Therefore, where /j/ occurs close to /i/, the latter may assimilate to and possibly replace the former. However the glide /j/ is not a common feature in Nigerian English, especially when it is preceded by a fricative.

The articulation of /ðɪs jɜː/ as [disie] as we heard from our respondents has phonetic underpinnings mostly involving articulatory mechanisms used during the realization of the voiced alveolar plosive /d/, which is closest to the dental region that occasions the realization of the dental fricative /ð/ rather than just mother-tongue interference. Shariatmadari (2006), for instance, strongly argues that phonological theory needs "Ease of Articulation" (EOA). It is basically unarguable that human articulatory organs pose series of constraints to speakers of any language during speech act. This explains the basic principle behind motor economy ― that certain sounds require more articulatory efforts than do others during realization and so the economy rests on those sounds requiring lesser energy or effort to articulate (cf Shariatmadari 2006). Moreover, such realizations can hardly impede intelligibility and may not constitute non-standard English since /i/ and /j/ appear to be variants (see Trask 1996).

One other phenomenon to glean from the performance of our respondents is that the realization of the retracted high, front vowel /ɪ/ as the neutralized version [i] is motivated by mother-tongue (MT) interference. Although this study is not particularly about vowels, yet it suffice to say in passing that most Nigerian MTs (except the Hausa language) do not have phonemic contrast for the front vowels /ɪ/ and /iː/ (see Jibril 1982; Jowitt 1991; Adetugbo 1977, 2004). The most obvious option, therefore, is to neutralize those vowels in contrastive environments (cf. Simo/Bobda/Chumbow 1999). Again, the closing diphthong [ɪə] is hardly realized in educated Nigerians repertoires. In fact, only three diphthongs are attested as phonemic in NigE: /aɪ/, /au/ and /ɔɪ/ (Awonusi 2004; Adetugbo 2004; Jibril 1982; Banjo 1996). Therefore, the realization of /ɪə/ as [ie] as if they are sequences of phonemes in [disie] would be admitted as MT interference. But again, this fact indicates the distinctive "Nigerianness" in the Nigerian English variety.

However, from table 2, it is clear that the variant designated as TY 1 (i.e. /khəʊtʃ him/) is not attested in NigE because the number articulating it is negligible compared to the total number of respondents. Besides, the form [kotʃim] was heard mostly among those from the Northern part of Nigeria, some of who were Hausa speakers. A few Yoruba and Igbo speakers pronounced the TY 4 version. From these explanations, we observe that the English language spoken by speakers from different parts of Nigeria is gradually diffusing into a form that could in future assume a national standard that would be typically described as a Nigerian accent of English (cf. Jibril 1982; Banjo 1995; Adegbija 2004).

Example 3: Coach him /kəʊtʃ hɪm/

The expression, "Coach him" is one of those that appeared on our corpus for the analysis of progressive assimilation. The Control realized the form [k həʊtʃ hɪm], which was an exponent of the SBE variant. But fifty-nine (59) out of the one hundred (100) respondents realized the form [kotʃim] (KH2) in which case the glottal fricative /h/ was phonetically elided.

Table 1 shows that the most significant item KH 2 [kotʃim] has 59 respondents. Only a paltry 7 respondents realized the SBE variant, [kəʊtʃ hɪm]. What is particularly striking here is that the h-deletion and h-insertion is phenomenal in Nigerian English (cf Awonusi 1985; 2004; Soneye 2007). Some educated Nigerians often pronounce words like history and half without the initial /h-/; perhaps the glottal fricative /h/ in this phonological environment requires some exertion.

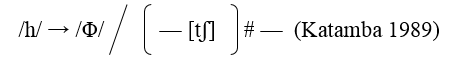

Besides, with regards to the instance of progressive assimilation observed between the final segment in "coach" (i.e. /tʃ/) and the initial segment in "him" (i.e. /h/), we have this explanation to give. Generally, as observed by Jowitt (1991), Jibril (1982), Eka (1985) and Awonusi (2004), the glottal fricative /h/ is significant for the majority of Nigerian English speakers. However, as pointed out in Awonusi (1985: 190–192) "many 'aitches' are identifiable in NEA". One of these "aitches" involves the "H-weakening and non-articulation or loss of /h/" (Awonusi 2004: 215). A second is the 'Categorical H-dropping' which implies the non-articulation of /h/ in h-full words. In the case of [kotʃim] realized by 59% of our subjects in which /h/ was totally eliminated, it is obvious that both processes described by Awonusi (2004) have applied such that the assimilating influence of the preceding segment /tò/ becomes perseverative, eliminating /h/ in the process. This observation is usually explained as a normal speech situation even among native speakers. This could be explained by the schema:

This schema indicates that: /h/ becomes deleted at initial position when preceded by the voiceless palato-alveolar affricate /tʃ/. Awonusi (2004) notes that this language performance is not peculiar to Nigerian English Accent (NEA), but also noticeable among RP speakers. We noticed this with the SBE subject that served as the Control, although he was very meticulous in realizing /h/. But in the short paragraph where the expression occurred in our corpus, it was actually [kəʊtʃim] and not [kəʊtʃ him] that the native speaker realized, meaning that in fast speech, the elimination of the glottal fricative /h/ is inevitable.

The other variant forms that occurred in the pronunciation of our respondents were [kɔtʃim] and [koʃim]. Six Hausa, two Fulani and one Nupe respondents realized the former variant (i.e.[kɔʃim]) while seven Yoruba, two Igbo, one Ijaw and one Fulani speakers articulated the latter. We had earlier explained that Yoruba speakers substitute /ʃ/ for /tʃ/ because the latter is not available in their mother-tongue. That of the Igbo speakers could be idiosyncratic because Igbo is known to have the variant [tj] phonemically (Jibril 1982; Awonusi 2004). Our experience on the items we have analyzed so far is that, if Nigerians realize such expressions like would you, has your, dash home, punish him, and so on, there are likely to be instances of progressive assimilation during which /h/ would be syncopated.

Based on the analysis of incidences of progressive assimilation we have attempted to examine so far, it becomes apparent to draw the conclusion that instances of perseverative assimilation of voice, place or manner of articulation are normal occurrences in NigE and do not just occur as incidences of fast or sloppy speech. Equally, the native speaker who served as the Control proves that this kind of assimilation occurs in SBE as an incidence of fast or sloppy speech.

The items on our corpus that illustrated instances of regressive assimilation include in case, would be defeated, and fiscal year. We intend to examine each of these expressions in an attempt to identify the nature of regressive assimilation that was noticeable with these items. As usual, we analysed the data both statistically and perceptually. The data are displayed on Tables 1 and 2 respectively.

Example 1: In case /ɪnkeɪs/

For the expression, in case, four variant forms were noticed in the respondents' renditions. The first variant coded "IC 1", (that is, [ɪn keɪs]) is an exponent of the RP model. It was the form realized by the Control. Only ten (10) respondents articulated this variant. The remaining 90% of the subjects realized the three remaining variants: IC 2, IC 3 and IC 4. We noticed in the result displayed in Table 1 that the variant, which exemplified the highest index of 66 representing 66%, with the highest statistically significant value is IC 4 that is [iŋ kes]. Two of the variant forms namely IC 2 and IC 4 showed clear cases of regressive assimilation. For instance, the last segment of the first word in is an alveolar nasal /n/ while the initial sound of the second word 'case' (i.e. /k/) is a voiceless velar plosive. From our data, we noticed that in the majority of cases, the respondents, in realizing the sound /n/ anticipated the place of articulation of the next segment /k/ which unavoidably conditioned the final segment of in (i.e. /n/) to [ŋ] phonetically, resulting in the form [iŋ kes]. This is a case of regressive (anticipatory) assimilation of place (RAP). The conditioning sound is /k/ and the assimilation site is where /n/ is replaced by /ŋ/, thus the influence moves backward affecting the alveolar nasal /n/.

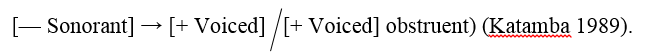

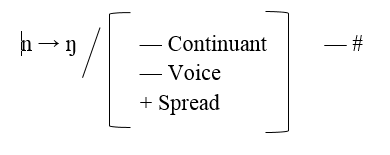

Our experience here reveals that most of the respondents found it extremely difficult to realize the alveolar nasal /n/ before the voiceless velar plosive /k/, therefore, in anticipation of the place of articulation of the next sound /k/, [ŋ] was realized instead, possibly as a diaphone of /n/. This accounts for why Jibril (1982: 80) remarks that "/n/ positionally conditions as [ŋ] before velars in NE". While we concede that the Control's performance exemplified the correct RP version, /ɪn keɪs/, we equally argue that many RP speakers (in an informal setting or in sloppy or fast speech) would have the same experience as the experimental group (EG). This is because the realization of in case /ɪn keɪs/ as [ɪŋ kes] by many of the respondents has some phonetic motivation rather than just MT interference, especially as the velar nasal /ŋ/ is not even present in the repertoire of especially Yoruba educated speakers of English and it could occur in the utterance of any other speaker of English anywhere in the world (whether native or non-native) once the phonetic conditions as well as the phonological environment that occasion them are fulfilled (cf. Shariatmadari 2006; Gimson/Cruttenden 1994; Katamba 1989). The diachronic case involving the word concrete justifies this claim.

One relevant explanation provided in Jibril (1982: 80) is that when the articulatory organs are in position for an exo-labial sound (that is, those sounds produced with the outer part of the lower lip caved inside the mouth and getting trapped under the upper teeth), it is easier to produce a velar than an alveolar nasal since the former position is relatively free. Generally, proponents of Natural Phonology (NP) admit that the articulatory constraints occasioned by human articulatory parameters determine the types of sounds that would emerge in certain phonological or phonetic environments (cf. Coates 1982; Anderson 1985). This theory, which was an outgrowth of the overall spirit of Generative Phonology (GP), has given vent to the emergence of language universals (cf. Jenkins 1996, 2000; Carey 2004).

One major generative account for the elimination of the nasal /n/ and the consolidation of /ŋ/ in this context is this:

The result is represented in the following schema:

Example 2: Would be defeated /wʊdbɪdɪ'fɪːtəd/

In connected speech, phonemes behave differently than what they are known to be originally. This is the case with the expression "would be defeated". Six variants of this expression were noticed among our informants (see table 2). The variant with the highest index is WD 1, [wʊd bɪ di'fɪted] which had 37 respondents representing 37% (table 1). This was followed by the WD 3 variant articulated as [wʊb bi di'fɪted] (34%). The RP variant which was realized by the Control is [wʊd bɪ dɪ'fiːtəd]. Only nine (9) respondents representing 9% articulated this variant. The least performance was noticed with the variant [wʊb bɪ di'piːted] which was observably realized by four Hausa and one Fulani speakers. Eight (8) of the respondents pronounced it as [wil bi di'fited] while seven produced the form [wu bi di'fited]. Our concern here is for the variants coded WD 3 and WD 4, that is, [wʊb bɪ di'fɪted] and [wʊ bɪ di'fɪted] respectively.

The WD 3 form [wʊb bɪ di'fɪted] indicated that a regressive voicing assimilation (RVA) has taken place. The voiced segment [d] is eliminated and replaced with [b] in an anticipatory manner. Usually, the alveolar plosive [d] is a voiced segment, but when it occurs in word final position, it may be devoiced. Voiceless segments are known to "copy" some features of a voiced sound in voiced environment. Sometimes, they are deleted following the influence of the voiced segment. In the case of would be /wʊd bɪ/ cited here, the final segment of the first word /d/ becomes devoiced while the influence of the fully voiced bilabial plosive [b] occurring in the initial position of the next word be moves backward "regressively" and takes over in anticipation of the articulation of the next segment /b/ resulting in [wʊb bɪ]. The incidence of consonant devoicing in final position is not surprising in this case because earlier studies have identified it as a key feature in Nigerian English (cf. Tiffen 1974; Bamgbose 1982; Adetugbo 1977; Trudgill/Hannah 1985; Awonusi 1987). The same episode is also reported in Cameroon English (Simo Bobda/Chumbow, 1999). We discovered that of those who realized the WD 3 variant, 3 were Hausa, 5 were Igbo and 9 were Yoruba speakers while the rest represented other languages.

That up to thirty-four (34) of the respondents articulated the WD 3 variant ([wʊb bɪ di'fited]) appears surprising, considering that they represent the acrolectal group of English users and speakers in Nigeria (Adetugbo 2004; Fakuade 1998; Banjo 1996). The implication of this is that, whether in in fast or casual speech, some Nigerians either replace or delete some sounds especially at word coda position, particularly voiced segments or those which appear in certain phonological environments. Again, that a large number of the speakers could not realize the RP variant shows that the Nigerian variety of English is distinctly different from that of the SBE variety. Therefore, in Nigeria an endonormative variety is already evolving, but more is required to standardize this model of English that is moderately distinct from the exoglossic, native-speakers' variety which seems almost unattainable in an L2 situation.

Example 3: Fiscal Year /'fiskl jɜː/

Another word on our corpus which exemplified an instance of regressive assimilation in Educated Nigerian Spoken English (ENSE) is the phrase fiscal year. Nine variant forms of this expression were noticed among our respondents. The form which showed the highest index of 35 representing 35% was ['fiskal jie] and was closely followed by the variant coded "FY 5" (i.e. ['fisika jie]) indicating the insertion of epenthetic vowel between the consonant cluster /s/ and /k/. The least index represented by "FY 8" appears to be abnormal and insignificant. The P-values that exemplified the most significant realizations with regards to this item were recorded against ['fikal jie] and ['fisika jie]. The third most significant realization was ['fisku jie]. The variant ['fiskl jɜː], which typifies the SBE pronunciation, occurred in the utterances of only two (2) of the respondents. The Control also realized this variant. It would appear that most of the respondents did not articulate the syllabic lateral /l̩/. Even the dark [ƚ] that was expected at this position did not occur in most of the utterances. The result rather shows that it was the clear /l/ that occurred mostly, followed by a second in which an epenthetic high back vowel [ʊ] was inserted between the voiceless plosive /k/ and the alveolar lateral /l/. Observably, the assimilating influence is regressive and it seems, in some cases, that the respondents substituted /l/ for /u/.

Awonusi (2004) observes that since there is some auditory similarity between /l/ and /u/, speakers may substitute the latter for the former. This is what is explained as L-vocalisation where /l/ is transformed into a vocalic sound (usually the vowel /u/). This shows why 14 of our respondents realized fiscal /'fiskl/ as ['fisku]. Many of the Yoruba respondents realized this form while many Igbo respondents realized the form ['fiska]. Seven (7) Hausa respondents realized the form ['pisikɑ] or ['fisikɑ]. This is because the Hausa language does not permit consonant clusters (like most Nigerian languages) and so tend to insert an epenthetic vowel (mostly /u/ and /i/) in a bit to separate such clusters (Jibril 1982). Some of the speakers from Hausa, Yoruba and some others from the minor group languages realized /jɪə/ as [jia]. However, the regressive assimilation that occurred was not phonetically motivated but came up as an amalgam of the two sounds in contact as a result of phonological environment. It is also important to note that the palatal glide /j/ generally elided in This year was articulated in Fiscal year by a considerable percentage of respondents (see table 1).

Generally, with our experience in this section, we are conjecturing that if Nigerians were to realize such expressions like both sides, ten men, one more, right place, in common, good time, big case, has she, and so on, they may likely encounter instances of regressive assimilation in the majority of cases. If this happens, then the conclusion we have drawn so far would be further consolidated, that assimilation is a normal occurrence among educated speakers of English in Nigeria and may slightly differ from the way it occurs with the native speakers.

One major item on our corpus that demonstrated the occurrence of homorganic assimilation was all right. Ladefoged (1982: 58) explains that when two sounds have the same place of articulation, they are said to be homorganic. For instance, the consonants /d/ and /n/, which are both articulated on the alveolar ridge, are homorganic. The same could be said of the lateral approximants /l/ and /r/ in the expression all right that we are considering here ― both are alveolar segments.

Five variant versions of the pronunciation of all right ['ɔːlraɪt] were heard among our respondents (see table 2). The version that had the highest index of fifty-two (52) was HA 1, that is ['ɔːraɪt]. The next with an index of thirty-six (36) respondents was HA 2, ['ɔːlraɪt] which was a close equivalent of the Control's variant ['ɔːlraɪt], except for the lengthening of the mid-back vowel [ɔ:]. One respondent realized a third variant ['hɔːlraɪt].

We noticed the occurrence of homorganic assimilation during the realization of all right by most of the respondents. It was phonetically motivated because during the articulation of the last segment of the first word all (i.e. /l/) in HA 2, the tongue-tip moved to the alveolar region and remained there to articulate the alveolar liquid (rolled) [r]. This may be viewed from the fact that the two segments are, in distinctive features parlance, [+ coronal]. However, in HA 2, the [ɔ] was made shorter because of the alveolar lateral approximant /I/ that followed. HA 1 variant was slightly different from HA 2 because in the former, the [ɔ:] was lengthened while the /I/ was eliminated to give room for the consolidation of the liquid (rolled) [r] which assumed the form of an apico-post-alveolar approximant [ɹ]. What is implied here is that the assimilatory process occurring in this instance results from two contiguous segments realized at the same place of articulation or pronounced with the same articulator, the alveolar ridge, but suggesting an instance of co-articulation with the retraction of the tongue backwards to the palatal region. It is possible to add that the tense vowel /ɔː/ (i.e. [+ tense]) may have occasioned the deletion of [l] and the subsequent consolidation of [r] in this position. This is what Jibril (1982: 174) considers as compensatory lengthening for consonant deletion.

Another explanation to this episode is given in Jibril (1982), Jowitt (1991) and Awonusi (2004). The explanation is that the syllable structure in most Nigerian languages does not permit consonant clusters. They are mostly monosyllabic with the CV or CVC structure, therefore, where there is consonant cluster, the obvious thing to expect is either the elimination or simplification of the structure, or the insertion of an epenthetic vowel between the consonants forming that cluster (cf. Jowitt, 1991: 81). This explains why our respondents deleted the lateral /l/ and consolidated only the post-alveolar liquid, /r/ instead.

In our earlier analysis of the expression "in case", we noted that the realization of the velar nasal /ŋ/ and the voiceless alveolar plosive /k/ constituted a case of homorganic nasal assimilation, apart from just being an instance of regressive assimilation, since both [ŋ] and [k] are realized at the same place of articulation.

Finally, the last two variants of the expression all right were ['hɔːlraɪt] and ['hɔːraɪt] which were rendered by two Yoruba speakers. This is understandable because, as Jibril (1982), Awonusi (2004) and Adetugbo (2004) have explained, Yoruba English speakers insert an aspirated /h/ into initial position of "h-less" words where they do not belong phonetically in normal English speech (see Awonusi 2004: 215).

This study has examined the nature of juxtapositional assimilation that characterizes the standard spoken English in Nigeria. In order to ensure that the subject is discretely treated, the authors adopted a corpus-based approach for a proactive result. Anchored on the conceptual categorization of juxtapositional assimilation exemplified in Abercrombie (1967), the work discussed instances of perseverative, anticipatory and homorganic assimilations. Both quantitative and qualitative approaches were adopted for its analysis and the results are presented in the tables and the chart. One hundred respondents were used as subjects for the study. One of the major discoveries in this study is that, in second language learning situation, phonological processes (especially assimilation), are inevitable among speakers and learners. Two, variant forms of assimilated segments are noticeable leading to phonological modifications during normal speech situations. Three, instances of phonological conditioning resulting from juxtapositional assimilation (as were observed in this study) though variant and numerous, do not impede intelligibility in a major way.

Again, while assimilation appears to be a feature of casual or sloppy speech among native speakers of the English language, it is found to be a normal occurrence in Nigerian English and in most second language situations, particularly, among the respondents we used because of a number of factors: mother-tongue interference, slower tempo of utterance, idiosyncratic patterns of realization, influence from socio-cultural and educational standards, social status, speech style, among others. Finally, this study is corroborated by other studies on the notion that the educated spoken English used in Nigeria is predominantly endonormative, and not exonormative. The implication is that there is the inevitable, implied need to evolve a standard and, possibly, a more uniform model of standard spoken English in Nigeria ˗˗ one that can facilitate effective communication both nationally and internationally.

Abercrombie, David (1967): Aspects of General Phonetics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Adegbija, Efurosibina (2004): "The Domestication of English in Nigeria". In: Awonusi, Segun (ed.) (2004): The Domestication of English in Nigeria: A Festschrift in Honour of Abiodun Adetugbo. Lagos, University of Lagos Press: 20–24.

Adetugbo, Abiodun (1977): "Nigerian English: Fact or Fiction?". A Journal of African Studies 4: 128–141.

Adetugbo, Abiodun (1978): "The Development of English up to 1914: A Socio-Linguistic Approach". Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria 9/2: 89–104.

Adetugbo, Abiodun (2004): "Problems of Standardization and Nigerian English Phonology". In: Dadzie, A. B. K./Awonusi, Segun (eds.) (2004): Nigerian English: Influences and Characteristics. Lagos, Concept: 179–199.

Akande, Akinmade (2012): Globalization and English in Africa; Evidence from Nigerian Hip-Hop. New York: NOVA

Anderson, Stephen (1985): Phonology in the 20th Century: Theories of Rules and Theories of Representations. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Awonusi, Victor (2004): "Some Characteristics of Nigerian English Phonology". In: Dadzie, A. B. K./Awonusi, Segun (eds.) (2004): Nigerian English: Influences and Characteristics. Lagos, Concept: 203–225.

Bamgbose, Ayo (1992): "Standard Nigerian English: Issues of Identification". In: Kachru, Braj (ed.) (1992): The Other Tongue: English across Cultures. Urbana, University of Iiinois Press: 99–111.

Bamgbose, Ayo (1995): "English in the Nigerian Environment". In Bamgbose, Ayo et al. (eds.) (1995): New Englishes: A West African Perspective. Ibadan, Mosuro: 9–26.

Banjo, Ayo (1970): "A Historical View of the English Language in Nigeria". Ibadan 28: 63–68.

Banjo, Ayo (1996): Making a Virtue of Necessity. An Overview of the English Language in Nigeria. Ibadan: Ibadan University Press.

Broshnahan, Leonard F. (1958): "English in Southern Nigeria". English Studies 39: 97–110.

Carey, Michael (2004): "Interlanguage Phonology: Sources of L2 Pronunciation Errors". Unpublished paper. http://www.google.ch/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&ved=0CCQQFjAA&url=http%3A%2F%2Fzephyr.nsysu.edu.tw%2Finterlanguage%2Frecord%2Fhandout%2F0225_0311%2Fphoneticsinsla.doc&ei=bNU0VfzkOYGTsgHb7IHoAQ&usg=AFQjCNGU1D81WZNMMnR0n5NYuf85sZsATw&sig2=jc19sSbHIgTM-FxWoHncCg, accessed April 15, 2015.

Chomsky, Noam/Halle, Morris (1968): The Sound Pattern of English. New York: Harper and Row.

Dinneen, Francis (1996): An Introduction to General Linguistics. London: Holt, Rinehart and Wiston.

Egbokhare, Francis (2003): "Breaking Barriers, ICT, Language Policy and Development". University of Ibadan Postgraduate School Interdisciplinary Research Discourse 2003. Ibadan: The Postgraduate School, U.I.

Eka, David (1985): Phonological Study of Standard Nigerian English. Unpublished PhD Dissertation, Ahmadu Bello University.

Eka, David (2000): Issues in Nigerian English Usage. Uyo: Scholar Press.

Elugbe, Ben (2006): "The LIC and the Cost of Language Development in Nigeria." A Paper Presented at the 20th National Conference of the Linguistic Association of Nigeria (CLAN), NERDC, Sheda, Abuja.

Elugbe, Ben/Omamor, Augusta (1991): Nigerian Pidgin Background and Prospects. Ibadan: Heinemann.

Fakuade, Gbenga (1998): "Varieties of English in Nigeria and Their Social Implications". In: Fakuade, Gbenga (ed.) (1998): Studies in Stylistic and Discourse Analysis. Yola, Paraclet: 123–136.

Gimson, Alfred Charles (1990): An Introduction to the Pronunciation of English. London: William Lowes.

Gimson, Alfred Charles/Cruttenden, Alan (1994): Gimson's Pronunciation of English. London/New York: Edward Arnold.

Grimes, Barbara F. (2000): Ethnologue. Vol. 1. Dallas: SIL International.

Gut, Ulrike (2002): "Nigerian English – A Typical West African Language?". Proceedings of TAPS, Bielefeld: 56–67.

Gut, Ulrike (2004): "Nigerian English: Phonology". In: Kortman, Bernd/Schneider, Edgar (eds.) (2004): A Handbook of Varieties of English. Amsterdam, de Gruyter: 813–830.

Gut, Ulrike (2005): "Nigerian English Prosody". English World-Wide 26/2: 153–177.

Gut, Ulrike (2007): "First Language Influence and Final Consonant Cluster in the New Englishes of Singapore and Nigeria". World Englishes 26/3: 346–359.

Hunjo, Henry (2002): "Pragmatic Nativization in Nigerian English". In: Adeyanju, Dele Samuel (ed.) (2002): Language, Meaning & Society: Papers in Honour of E. E. Adegbija at 50. Ilorin: Haytee: 51–68.

Hyman, Larry (1975): Phonology: Theory and Analysis. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Igboanusi, Herbert (2001): A Dictionary of Nigerian English. Ibadan: Sambook.

Ike, Ndubuisi (2001): English Language in Nigeria – with an Overview of English in the World. Enugu: Wilbest.

Jenkins, Jennifer (1996): "Changing Pronunciation Priorities for Successful Communication in International Contexts". In: Speak Out 17: 15–22.

Jenkins, Jennifer (2000): The Phonology of English as an International Language: New Models, New Norms, New Goals. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jibril, Munzali (1979): "Regional Variation in Nigerian Spoken English". In: Ubahakwe, Ebo (ed.) (1979): Varieties and Functions of English in Nigeria: 43–53.

Jibril, Munzali (1986): "Sociolinguistic Variation in Nigerian English". English World-Wide 7/1: 47–75.

Jibril, Munzali. (1982). "Phonological Variation in Nigerian Spoken English" Unpublished PhD Dissertation, University of Lancaster.

Josiah, Ubong/Babatunde, Sola Timothy (2011): "Standard Nigerian English Phonemes: The Crisis of Modelling and Harmonization". World Englishes 30/4: 533–540.

Josiah, Ubong (2014). "Multilingualism and Linguistic Hybridity: An Experiment with Educated Nigerian Spoken English". Review of Arts and Humanities . 3/2. American Research Institute for Policy Development. 157-184.

Jowitt, David (1991): Nigerian English Usage: An introduction. Lagos: Longman.

Jowitt, David (2007): "Standard Nigerian English: A Re-Examination". Journal of the Nigerian English Studies Association 3/1: 1–21.

Katamba, Francis (1989): An Introduction to Phonology. New York: Longman.

Ladefoged, Peter (1982): A Course in Phonetic. Harcourt Brace: New York.

Odumuh, Adama (1987): Nigerian English. Zaria: University Press.

Okoro, Oko (2004): "Codifying Nigerian English: Some Practical Problems and Labelling". In: Awonusi, Segun (ed.) (2004): The Domestication of English in Nigeria: A Festschrift in Honour of Abiodun Adetugbo. Lagos, University of Lagos Press: 166–181.

Peng, Long/Ann, Jean. (2001): "Stress and Duration in Three Varieties of English". World Englishes 20/1: 1–27.

Roach, Peter (1997): English Phonetics and Phonology: A Practical Course. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Shariatmadari, David (2006): "Sounds Difficult? Why phonological Theory needs 'Ease of articulation'". SOAS Working Papers in Linguistics 14: 207–226.

Simo Bobda, Augustin (1995): "The Phonologies of Nigerian English and Cameroon English." In: Bamgbose, Ayo/Broshnahan, L. F. (1958): "English in Southern Nigeria". English Studies 39: 97–110.

Simo Bobda, Augustin (2003): "Segmental features, Regional and National features". English World-Wide 24/1: 17–42.

Simo Bobda, Augustin (2010): "Word Stress in Cameroon and Nigerian Englishes". World Englishes 29/1: 59–74.

Simo Bobda, Augustin. (1995): "The Phonologies of Nigerian English and Cameroon English". In: Bamgbose, Ayo et al. (1995): New Englishes: A West African perspective. Ibadan, Mosuro: 248–268.

Simo Bobda, Augustin/Chumbow, Bebban (1999): "The Trilateral Process in Cameroun English Phonology Underlying Representations and Phonological Processes in Non-Native Englishes". English World-Wide 20/1: 35–65.

Simo Bobda, Augustine (2007): "Some Segmental Rules of Nigerian English Phonology". English World-Wide 28/3: 279–310.

Soneye, Taiwo (2007): Phonological Sensitivity of Selected NTA Newscasters to Polyphonic and Polygraphic Phenomena in English. Unpublished PhD Dissertation, University of Ibadan.

Tiffen, Brian (1974): The Intelligibility of Nigerian English. PhD Dissertation, University of London.

Trask, Larry (1996): A Dictionary of Phonetics and Phonology. New York. Roultledge.

Trudgill, Peter/Hannah, Jean (21985): International English: A Guide to Standard English. London: Edward Arnold.

Udofot, Inyang (2003): "Stress and Rhythm in the Nigerian Accent of English: A preliminary Investigation". English World-Wide 24/2: 201–220.

Udofot, Inyang (2004): "Varieties of Spoken Nigerian English". In: Awonusi, Segun (ed.) (2004): The Domestication of English in Nigeria: A Festschrift in Honour of Abiodun Adetugbo. Lagos, University of Lagos Press: 93–113.

Wells, John (1982): Accounts of English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Yule, George (21996): The Study of Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.