http://dx.doi.org/10.13092/lo.75.2515

Lectures are requisite of most academic classroom settings, and teachers see them as a meaning making event. However, this is one side of the coin, and the other side lies in the students’ mutual understanding of what the lecturer presents in his speech. The perfect understanding of lectures can guarantee academic success. Studies have shown that understanding lectures is not an easy task (cf. Jordan: 1997; Young: 1994). Due to the significant role of lectures in the academic life of students, several studies have analyzed different aspects of academic lectures to enhance our understanding of academic lecture discourse and to provide students with clues on how to process the information in lectures. The aspects analyzed include lectures in the reading style studied for macro and micro markers (cf. Chaudran/Richards: 1986), the overall structure of lectures (cf. Dudley-Evans: 1994; Thompson: 1994, 2003; Young: 1994), lecture introductions (cf. Lee: 2009), the use of asides (Strodt-Lopez: 1991), the use of personal pronouns (Fortanet: 2004; Cheng: 2012), authenticity in academic listening comprehension (cf. Flowerdew/Miller: 1997), the communicative needs of academic learners (cf. Ferris/Tagg: 1996), interactivity and the structure of lectures (cf. Camiciottoli: 2004; Jung: 2006; Morell: 2004, 2007), class size and macrostructures of academic lectures (cf. Lee: 2009), class size and lecture closing (cf. Cheng: 2012), the conversational characteristics of lectures (cf. Simpson-Vlach/Elis: 2010), metadiscourse (cf. Adel: 2010), discourse markers (cf. Allison/Tauroza: 1995; Jung: 2003, 2006), interactional and structural functions of academic lectures (cf. Schleef: 2009), lexico-grammatical marking of less important points (cf. Deroey/Taverniers: 2012), and the structural analysis of lexical bundles (cf. Kashiha/Heng: 2014). However, classroom lecture closings have not received much attention in academic discourse studies (cf. Cheng: 2012). While a classroom lecture shares certain common elements with formal speech, it also stresses the importance of teacher-student interaction in general (cf. Morell: 2007) and classroom lecture closings in particular.

If not more important than its opening or content, the closing of a lecture is no less significant. Generally, a powerful ending in any lecture, including lectures in university settings, can impress the audience and convey the importance of the message. The closing is an opportunity for the lecturer to wrap up the teaching content, review or summarize the important points, and explain some course and content-related issues (cf. Cheng: 2012). Besides, students can benefit from this opportunity to ask for more content clarification or ask any other type of questions. The closing is where the weight of teaching is lifted off the lecture and both the student and the lecturer experience a sense of relief. They can discuss the points in their minds more freely. These moments can deepen the interpersonal relationships between the student and the teacher especially in interactive classes compared to those that are monologic. Therefore, the analysis of this part genre has the benefit of familiarizing novice teachers and students with spoken academic language.

The way lecturers organize their speech is very much dependent on their individual styles. Thus, students need to be aware of different strategies used by different teachers in this communicative event (cf. Cheng: 2012). As a result, this awareness might increase the level of the students’ understanding when taking courses with different teachers with unique styles. Another factor increasing the students’ academic success is the quality of the interpersonal relationship between them and their teacher. The more the teacher plays an interactive role in the process of knowledge transfer, the more he creates a tension-free environment where students can overcome existing affective barriers when seeking help and when sharing their ideas and feelings. The post-ending stage of a lecture is actually the part in which this tensionless interaction occurs. Good human relationship facilitates productivity, comprehensibility, and achievement. Teachers would rather use “cordial relations between themselves and students” and take into account that a “healthy interpersonal relationship is one indispensable instrument of high productivity and achievement in all fields of human endeavor including the education industry” (Fan 2012: 483). Therefore, a detailed analysis of the strategies employed by both teachers and students in a lecture closing helps enhance our knowledge of the interactive nature of lecture post-endings. Although the new concepts of flip teaching and upside down classroom have attracted the attention of scholars, there is still a long way to assume the implementation of these classes due to practicality issues in most of the settings especially at the under graduate levels which is the focus of this study.

Given the crucial role of closing and the little attention paid to this part of a lecture, a compelling need is felt for further studies in this domain. The most recent research on the organization of lecture closing in English academic settings was conducted by Cheng (2012). She identified the steps and strategies in academic lecture closings in English communities. Despite her comprehensive analysis of the rhetorical structure of English academic lecture closings, the research bore some limitations. Cheng (2012) used the MICASE corpus (university lectures recorded at the University of Michigan between 1997 and 2001), which draws on the following principles: First, the data were not from a recent corpus (i. e., collection of texts or transcribed verbal data). It belonged to the previous decade, so the probable changes in academic lecture structures over time were neglected. Second, as Cheng (2012) used corpus-based data, she missed face-to-face non-verbal cues which constitute important aspects of lecturing. To overcome these limitations, the data used in the present study were gathered in late 2012. The on-site data collection and recordings, and the access to spoken language contrary to the transcribed data Cheng (2012) used, provided us with the opportunity to interpret both verbal and nonverbal interactions. Furthermore, as far as the existing literature is concerned, there seems to be a dearth of research exploring the rhetorical structure of Persian lecture closings. Exploring Persian language settings is significant in two respects: First, Persian is the standard language of academic lectures in Iranian universities with the exclusion of lectures in foreign languages departments. Second, unveiling Persian language structures of lecture closings as well as the level of formality will help inform novice or prospective lecturers of the organizational patterns of lecture closings. Most studies in academic contexts have focused on English as the medium of instruction in first and second language academic settings. Notwithstanding the merits of such studies to the development of our knowledge of academic lecturing, further studies in non-English academic settings enhance our understanding of lectures and how they are structured and delivered in other languages. Given that the literature on academic lecture closings is still in its embryonic stage, and that it has widely overlooked lectures delivered in other languages, it is important to conduct further studies to analyze features of academic lectures in order to assist students in inferring the speaker’s intention and goals.

The present study is intended to investigate the organizational features of Persian academic lecture closings. Moreover, this study seeks to explore the level of formality and the probable use of nonverbal cues as the indicator of lecture closings. Understanding, analyzing, and comparing the assumed formality and distance between lecturers and students in different educational settings across the world will provide insightful accounts about the cultural and interpersonal relations and also help novice teachers to be aware of the established norms. In a cross-cultural study, Schleef (2009) maintained that German academic discourse was more formal through the use of group vocatives compared to American academic settings. Comparing the formality level of interactions in different academic settings and their probable influences on students’ class participation and learning achievements will provide perceptive and clear-sighted interpretations that might lead to promising results.

Taking previous studies as a point of departure, this study aims at answering the following questions:

1. What is the organizational characteristic of Persian academic lecture closings?

2. Do Iranian instructors use more nonverbal or verbal cues as the termination point of their academic lectures?

How do Iranian instructors use the second person pronoun shoma (formal you) or to (informal you) in Persian to establish either a formal or informal relationship with their students in classes?

A total of 100 lectures (approximately 185 hours) in Persian recorded from different universities in both hard and soft sciences, including computer, electronic and chemical engineering, veterinary medicine, mathematics, accounting, management, psychology, and law, were collected to study the closing sections of authentic academic lectures at the undergraduate level. For the sake of diversity, the class of each lecturer was observed and recorded once. To enhance the applicability and generalizability of our findings, we attempted to study both hard and soft sciences. The aforementioned fields are among the most established representatives of hard and soft sciences. Computer engineering, electronic engineering, chemical engineering, veterinary medicine, and mathematics, the representative of hard sciences, constituted 50 of the lectures. Accounting, management, psychology, and law, as examples of soft sciences, accounted for the other 50 lectures. The last fifteen minutes of each lecture was transcribed for the purpose of the study. It is worth mentioning that the last quarter of the class hour is not a fixed time point for lecture closings. While in some classes the closings took at least fifteen minutes, there were some lectures which ended much earlier or even ended abruptly. To be consistent and to avoid confusion in studying the stages, we agreed upon transcribing the last fifteen minutes. The transcribed data contained approximately 1500 minutes, (25 hours). The total amount of the transcribed data came out of the multiplication of the last fifteen minutes of the recorded Persian-speaking lectures. To identify and use both non-verbal and verbal cues in lecture closings, we personally attended and audio-recorded the lectures. Therefore, the analyses were based on our personal observations and recordings.

The framework used in the analysis was characterized by the generic features (i. e., meaning signifiers) of this genre. Following Cheng (2012), we decided to use the terms “strategy” and “stage” instead of Swales’ (1990: 166) “moves” and “steps” or Thompson’s (1994: 172) “functions” and “sub-functions”. According to Cheng (2012), the term strategy is used to emphasize the non-sequential and recurrent nature of elements in the framework. The term stage is used to reflect the upper-level structure, and the sequential process of lecture closings (Cheng 2012: 236). Simply put, strategy is comparable to moves (i. e., rhetorical tactics writers use to achieve communicative purposes) in genre analysis. Similar or different strategies may occur at any stage of the lectures.

As the starting point, we conducted a pilot study. We selected a quarter of the main data randomly (25 lectures) and separately ran a preliminary analysis on them in order to identify the underlying strategies. Wherever there were disagreements on identifying strategies and stages, we discussed the discrepancies until an agreement was achieved. In the next phase of the study, the remaining 75 lectures, in addition to the lectures in the pilot study, were analyzed for the main analysis.

The rhetorical structure of a lecture closing was divided into pre-ending, ending, and post-ending stages. The pre-ending stage is when the lecturer does not offer new information on the teaching content and gets ready to end the lecture by assigning homework, making clarifications about the exam, and summarizing and reviewing the important points of the lecture (cf. Cheng 2012: 237). The ending stage “follows the pre-ending stage” but, as Cheng (ibd.) mentions, “it is the first stage identified in the analysis” for the lecturer’s statements, including explicit ending expressions such as course plans for the following sessions, authorizing students to leave, and “leave-taking goodbyes and good wishes”. The post-ending stage follows the ending stage and deals with activities and interactions between students and the lecturer after he has explicitly announced the end of the class.

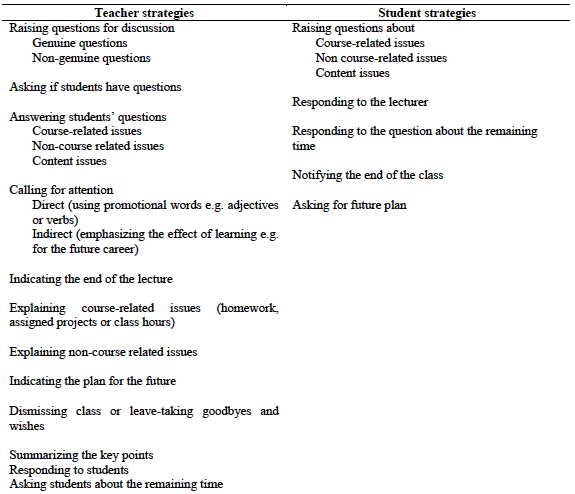

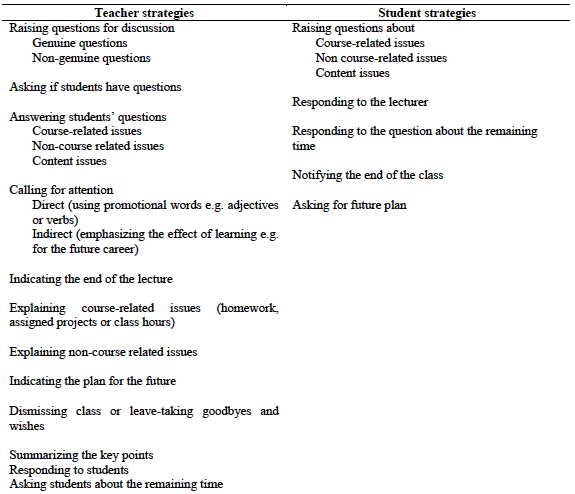

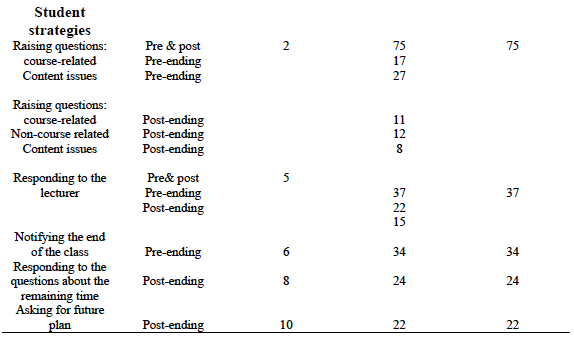

In describing the structure of a research article, Swales (2004: 228) defines moves as “discoursal or rhetorical units that perform a coherent communicative function in a written or spoken discourse”. Strategies are similar to moves and they are also identified based on their communicative functions (cf. Cheng: 2012: 237). In every stage of this study, a number of strategies were identified and their occurrences were examined to find what the organizational patterns of the stages were and how the lecturers employed strategies for their communicative purposes. Strategies were divided into two categories: student strategies and teacher strategies. Since teachers play a more powerful role in Persian-speaking classroom contexts, the number of strategies which they employ naturally exceeds the number of student strategies. As a final step, we validated our selection of the strategies by inviting two experienced lecturers to judge our choices. To avoid reader confusion, we did not codify the strategies throughout the study. Contrary to Cheng (ibd.), we did not use arbitrary signs or codes for each strategy since codifying (using simple codes to refer to each strategy) the relatively long list of strategies might lead to more confusion rather than convenience as the reader has to check or memorize the codes which stand for each strategy. The following table displays both types of strategies:

Table 1: Strategies in lecture closings

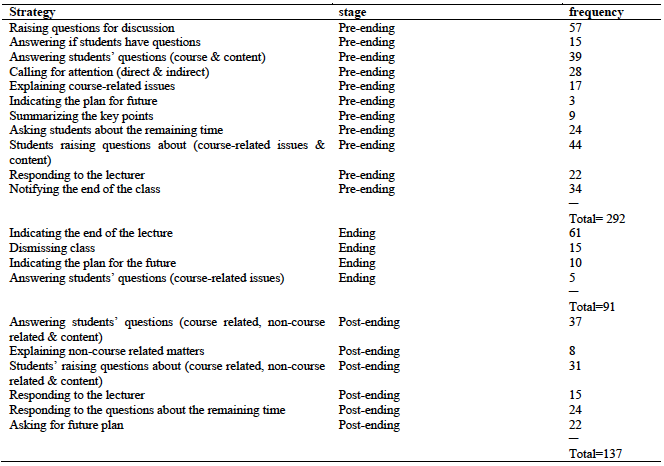

An examination of the occurrences of the strategies across the three stages (Table 2) showed that the pre-ending stage had the highest occurrences of strategies (292) followed by the post-ending stage (137), while the ending stage included the least occurrences of strategies (91). However, the pre-ending stage constituted more major types of strategies (11 types) than the ending (4 types) as well as the post-ending stages (6 types). Among the strategies, answering students’ questions (a teacher strategy), raising questions (a student strategy), indicating the end of the lecture (a teacher strategy), and raising questions for discussion (a teacher strategy) were the most used, respectively.

Table 2: Distribution of teacher and student strategies in Persian lecture closings

In the pre-ending stage, the majority of strategies were teacher-oriented (8 teacher strategies, 3 student strategies), while in the ending stage no instance of student strategies was seen (4 teacher strategies). The strategies in the post-ending stage were more student-oriented (4 student strategies, 2 teacher strategies); tacitly indicating that in these settings, students are more willing to initiate interaction with the teacher after the class formally ends. The moments of the post-ending stage are apparently less threatening for students so that they can start the interaction with the teacher freely. It seems that the degree of formality and distance the students assume to the lecturers in Persian-speaking classes is relatively high during the formal class time. As soon as the class finishes, the students start to communicate with the teacher and perhaps ask questions they did not dare to ask. It is noteworthy that in Cheng’s (2012) study on English academic settings almost all strategies in the three stages were teacher-oriented.

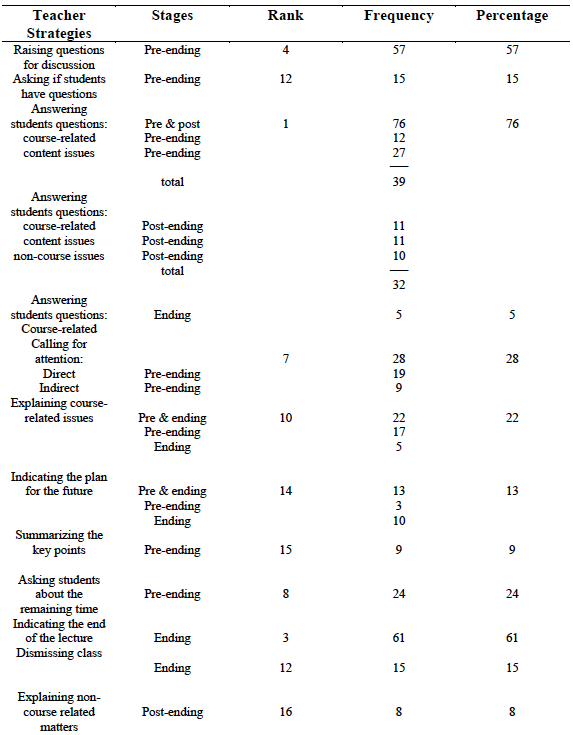

Table 3: Distribution, rank, and percentage of strategies in the three stages of Persian lecture closings

In the present study, the most frequent strategies clustered respectively in pre-ending, post-ending, and ending stages. This sequence shows some discrepancies with what Cheng (2012) found in her study on English lecture closings. In her study, in terms of the frequency of strategies in each stage, the stages were respectively sequenced as pre-ending, ending, and post-ending stages (cf. ibd.: 238).

As revealed in Table 3, some strategy use suggests flexibility in the stages. In other words, some strategies may appear in two or all three stages. For example, answering students’ questions regarding course-related issues occurred in all three stages (though with different frequencies), and indicating the plan for the future occurred three times in the pre-ending stage and ten times in the ending stage.

The analysis revealed that most lecture-closing strategies in Persian-speaking settings clustered in the pre-ending stage. This finding is contrary to Cheng’s study (2012) which showed that the strategies were mainly gathered in the ending stage. Cheng (2012: 239) justified that the most occurrences of strategies in the ending stage were due to the fact that “not many lecturers actually wrap up the lecture by summarizing the key points, having a discussion of the lectures, and so forth”. However, the most occurrences of the strategies in the pre-ending stage in Persian academic settings do not necessarily mean that lecturers carefully wrap up the lecture by making a summary or discussion. As Table 2 displays, the strategy of summarizing the key points was used only 9 times and the frequent use of the strategy of raising questions for discussion was mainly related to the non-genuine questions which were used for introducing the new content for student’s further studies or what they will learn in the following sessions, without expecting students to answer these new contents. These questions are not genuinely challenging questions. Moreover, in Persian-speaking settings, the number of questions raised by students and the related answers from teachers are relatively much higher than the frequency of such questions in Cheng’s study (2012). Considering the fact that in English settings the majority of strategies occur at the ending stage, not at the pre-ending stage, the differences seem reasonable.

In Iranian academic settings, the three teacher strategies of raising questions for discussion, answering students’ questions, and indicating the ending of a lecture are generally the most occurring strategies. However, this is not the case with English academic discourse. Following Cheng’s (cf. ibd.: 237) suggestion, the three teacher strategies of indicating the end of the lecture, explaining future course plans, and dismissing the class are the three most frequently used strategies in English settings. While the dismissing the class strategy that normally follows the teacher’s indicating the end of the lecture strategy is frequent in English academic discourse (ibd.), this does not happen in Persian-speaking settings. In fact, indicating the end of the lecture means dismissing the class, for both students and teachers. As we observed in our data, the students would not wait to be given permission to leave class. In many cases, they had already left class. The following examples show these highly frequent strategies in Persian-speaking contexts:

(1) Be nazar-e shoma naghshe in mafsal dar harekate asb chiye?

((به نظر شما نقش این مفصل درحرکت اسب چیه؟

(Pre-ending stage, veterinary medicine, raising a question about the content to make sure the students learned the lesson. 5/11/2012)

[‘In your opinion, what role does this joint play in the movement of the horse?’]

(2) ehtemalan in moshkel be dalile click kardane hamzaman ruye chand file etefagh oftade.

(احتمالا این مشکل به دلیل کلیک کردن همزمان روی چند فایل اتفاق افتاده.)

(Pre-ending stage, computer engineering, responding to questions, 7/11/2012)

[‘This problem might have happened because of simultaneous clicking on some files.’]

(3) khob ta haminja base.

(خب، تا همین جا بسه)

(Ending stage, law, indicating the end of the lecture, 7/11/2012)

[‘That’s enough for today.’]

In this section, we discuss each strategy separately along with the related sample utterances from Persian lecture closings. In addition, the findings of the present study will be compared with Cheng’s (2012) study on academic lecture closings in English settings to identify the probable similarities and differences.

One of the frequent strategies in Persian academic lectures was raising questions for discussion subcategorized as genuine and non-genuine questions. Asking a non-genuine question on the part of the teacher has not been mentioned in Cheng’s (2012) study on academic English lecture closings. In Persian academic lectures, we observed that teachers asked questions but they did not expect students to answer. Instead, the teachers themselves provided the answer promptly. This prompt reply was considered as their teaching strategy while reviewing the content or sensitizing the students mind for further research. This strategy is shown in the following examples.

* A genuine question:

(4) Agar zan az moraje-e be daftare talagh khoddari kard, mard che kari mitavanad anjam dahad? (Law, 13/11/2012)

(اگر زن از مراجعه به دفتر طلاق خودداری کرد، مرد چه کاری می تواند انجام دهد؟)

[‘What can the husband do if his wife refuses to attend divorce records department in person? (The teacher waits for the answer. He wants to check if the students have learned the lesson or not.’]

* A non-genuine question:

(5) Chera bacheha dar in mogheiyat lajbazi mikonan? Chon mikhan tavajohe digaran ro jalb konan. (Psychology, 13/11/2012)

(چرا بچه ها در این موقعیت لجبازی میکنن؟ چون میخوان توجه دیگران رو جلب کنن.)

[‘Why do children get stubborn in this situation? Because they want to attract others’ attention. (The teacher didn’t wait for the answer. He assumed that the students know the answer since the content was repeatedly mentioned during the class.’)

The next strategy is asking if students have questions that occurred at the pre-ending stage in Persian academic settings. Fifteen lectures contained this infrequent strategy. This strategy was not very frequent in English lectures either (only 9 times), as Cheng (2012: 238) claimed. It seems that in both Persian and English settings the teachers came to the conclusion that they had explained the content clearly and completely enough, so there was no need to ask the students if they had any questions. The following example represents this strategy:

(6) khob soali hast? (Chemical engineering, 12/11/2012)

(خب سوالی هست؟)

[‘Any question?’]

Answering the students’ questions took three forms of course-related, non-course related, and content questions. This strategy was the most frequent of all in Persian settings (76), whereas it was infrequent in English lectures (11) as reported by Cheng (2012). Tentatively, we may attribute this difference to the target-oriented nature of the questions in Persian settings. Note the following examples:

(7) Course-related answers: emtehan az faslhaieye ke dars dade shod. (Computer engineering, 12/12/2012)

(امتحان از فصلهاییه که درس داده شد.)

[‘The covered chapters will be included in the exam.’]

(8) Non-course related answers: baraye emtehane arshad behtare ke majmoe soalato bekhonid. (ibd.)

(برای امتحان ارشد بهتره که مجموعه سوالات رو بخونید.)

[‘To be prepared for the MS exam, you’d better read the exam questions package.’]

(9) Content related answers: bekhatere kesheshe molokuliye. (Chemical engineering, 17/12/2012)

(به خاطر کشش مولکولیه.)

[‘This is because of molecular tension.’]

The strategy of calling for attention, occurring 28 times in Persian academic settings, was divided into direct and indirect subcategories. The Persian lecturers used the direct strategy (19) times and the indirect strategy (9) times to attract the students’ attention, whereas it occurred only four times in Cheng’s (2012: 238) study. In the direct strategy, lecturers explicitly used words such as be careful, important, notice and so on to draw the students’ attention while in the indirect strategy, the lecturer laid emphasis on the importance of the topic based on its future use in exams or a future career:

[10) Direct: deghat konin. In nokte kheily moheme. (Chemical engineering, 17/12/2012)

(دقت کنین. این نکته خیلی مهمه.)

[‘Keep in mind. This is a very important point.’]

(11) Indirect: az in ghesmat hatman ye soal vase arshad miad. (Chemical engineering, 17/12/2012)

(از این قسمت حتما یه سوال واسه ارشد میاد.)

[‘There will surely be a question in MS exam from this part.’]

Indicating the end of the lecture is the third highly frequent strategy adopted by Persian academic lecturers (61), while it occurred 23 times in Cheng’s (2012: 238) study. This strategy marks the ending stage and is utilized by lecturers both verbally and non-verbally in Persian academic settings. It was observed that quite a few teachers did not use verbal cues as the indicator of the end of the lecture. They sometimes just closed their books or looked at their watches or capped their markers to signal the end of the session. (See section 3.4. for non-verbal endings).

(12) Khob ta inja kafie. (19/12/2012, Psychology)

(خب تا اینجا کافیه.)

[‘Well, that’s enough.’]

Explaining course-related issues, occurring in both pre- and post-ending stages 22 times regarding assignments and projects, was almost low in Persian academic settings, though slightly higher than its occurrence in Cheng’s (2012) research (16). Notably, the strategy of explaining course-related issues was mainly used in engineering classes where the students were assigned projects or homework or class-hour management for laboratory participation. Note the following examples:

(13) gorohe 3 hafte ba’d sa ate 2 bashan azmayeshgah (Chemistry, 17/12/2012)

(گروه سه هفته بعد ساعت دو باشن آزمایشگاه.)

[‘Group 3 should attend the laboratory at 2:00 next week.’]

(14) Doshanbe hafteye ba’d sa ate 2 jobrani darim. (Veterinary, 19/12/2012)

(دوشنبه هفته بعد ساعت دو جبرانی داریم'.)

[There will be a make-up session at 2:00 next Monday’]

Indicating the plan for the future occurring 13 times in Persian-speaking settings was also a less frequent strategy. The lower use of this strategy cannot be certainly attributed to the students’ being provided with the lesson plan at the beginning of the semester. This is certified by the student strategy of asking for future plans through which the students demanded that they be informed of what the teacher was going to do for the following session (22). It seems that the lecturers did not take the responsibility of preparing students for the next session’s schedules, and they kept the students in dark. In contrast, in the English setting, indicating the plan for the future was the most frequently utilized strategy by lecturers (Cheng 2012: 238). Note the following example in Persian:

(15) jalase baad C++ ro shoro mikonim. (Computer engineering, 29/11/2012)

رو شروع میکنیم) C++(جلسه بعد

[‘Next session, we will start C++.’]

Dismissing class or leave-taking goodbyes and wishes with the occurrence of 15 was not a common strategy used by Persian-speaking lecturers to indicate the ending stage. Students take the strategy of indicating the end of the lecture which normally precedes the dismissing class strategy as permission to feel free to leave the classroom. However, dismissing class or leave-taking goodbyes and wishes was the third frequent strategy in Cheng’s (2012: 238) English-speaking settings. Note the following example of dismissing class in Persian:

(16) Befarmaieen. (Computer engineering, 29/11/2012)

(بفرمایین)

[‘Class, dismiss.’]

Another low frequency strategy in Persian academic settings is summarizing the key points (9). Unfortunately, the teachers did not bother themselves to give the gist of the lecture content at the end of the session and left making heads or tails out of the content to the students. This finding is in line with Cheng’s (2012: 238) in which the same strategy in English settings occurred only three times. The following example represents this strategy in the Persianspeaking lecture pre-ending:

(17) Pas emruz raveshhaye moghabele ba bachehaye lajbaz ro barasi kardim. (Psychology, 13/11/2012)

(پس امروز روشهای مقابله با بچه های لجباز رو بررسی کردیم.)

[‘So, today we discussed the ways to treat stubborn children.’]

The last teacher strategy being discussed here seems unique to Persian-speaking settings. The strategy of asking students about the time remaining which was mainly used in pre-ending stage occurred in 24 lectures. Actually, based on what we observed in classes this cannot be necessarily assigned to the teachers’ having lost the track of time. The lecturer sometimes used this strategy as a preparatory sign to indicate the end of the session. There were several cases in which the teacher checked the time by looking at his watch but again asked the students about the amount of time remaining.

The strategy of raising questions by students is subdivided into course-related, non-course related, and content issues. It is the second most frequent strategy in Persian lecture closings. Raising questions about course-related issues and content issues occurred in both pre- and post-ending stages, while raising questions about non-course related issues only occurred in the post-ending stage where students felt less tension which encouraged them to ask their questions freely. As Table 3 demonstrates, raising questions about content issues is more frequent than the other two instances (course and non-course related issues). In addition, of the course-related and non-course related questions, the former took precedence over the latter. Questions about course and content issues occurred more frequently in the pre-ending than in the post-ending stage. This means that the students are not obliged to postpone asking their questions to the post ending stage. This implies that teachers generally welcome the students’ questions at any moment. Nevertheless, the students prefer not to ask non-course related issues in the pre-ending stage and wait until the teacher declares the end of the session. The following examples show this highly frequent strategy:

(18) Course-related example (Electronic engineering, 2/12/2012, pre-ending)

Student: ostad mishe in prozharo ta baad az emtehane term tahvil bedim?

(استاد میشه این پروژه هارو تا بعد از امتحان ترم تحویل بدیم؟)

[‘Teacher, is it possible to submit the project at the end of the semester?’]

(19) Content-related example (Psychology, 25/12/2012, pre-ending)

Student: vaghti ke nemitunim moraje konandaro ghane konim ke dare raho eshtebah mire, chi kar bayad kard?

(وقتی که نمی تونیم مراجعه کننده رو قانع کنیم که داره راهو اشتباه میره، چیکار باید کرد؟)

[‘What should we do to convince the client when he’s taking the wrong way?’]

(20) Non-course related example (Law, 25/12/2012, post-ending)

Student: ostad, shoma vaseye azmun vekalat amuzeshgahe khasiro nemishnasid ke karesham khoob bashe?

(دانشجو: استاد. شما واسه ی آزمون وکالت آموزشگاه خاصی رو نمیشناسید که کارشم خوب باشه؟)

[‘Teacher, do you know any qualified institute for lawyers’ entrance test preparation?’]

The next student strategy, responding to the lecturer, with the frequency of 37, occurs in both pre- and post-ending stages. In the English academic lectures of Cheng’s (2012: 238) study, this strategy was the second most frequent strategy occurring 34 times in the data (56). This means that students in both settings take their interactive role seriously. In fact, in Persian-speaking settings the act of responding mostly occurred in pre-endings as in this stage the lecturers raised most of their questions. The fact that the frequency of responding to the lecturer exceeds the number of questions raised by teachers is attributed to several answers given by different students to the same question. An example of this strategy is provided below:

(21) Responding to the lecturer example (Chemical engineering, 20/12/2012)

Student: shayad kesheshe sathi moasere.

(دانشجو: شاید کشش سطحی موثره.)

[‘Maybe the surface tension is effective.’]

Responding to the question about the remaining time with the occurrence of 24, as the consequence of asking about the remaining time by lecturers, was observed in Persian academic settings. As this strategy was not reported by Cheng (2012), it appears that it is a typical characteristic of Persian academic settings.

The unusual but interesting strategy of notifying the end of the class (34) was adopted by students to signal that time is over. Seemingly, the students explicitly showed their reluctance to stay in the class for different reasons. They expected their teachers to finish the course material in the allotted time or even sometimes before it. In one case, the students and the teacher started a discussion over whether to stay or leave the classroom. The students finally found their way to finish the class. The following example is typical in many Persian classes:

(22) Notifying the end of the class example (Accounting, 6/12/2012)

*Student: ostad, khaste nabashid.

(*دانشجو: استاد. خسته نباشید.)

[‘Let’s call it a day. (In old literary texts, the expression “more power to your elbow” was used).’]

Asking for future plans occurred in 22 Persian-speaking lectures. Normally, this is the role of the teacher to indicate future plans. But, here the students were not clear about the course syllabus. The students informed the researchers that they had not been provided with the course syllabus at the beginning of the semester. Although not having a lesson plan was common in the classes of some fields, the students of engineering worried more about what they were expected to do for the following session. The reason might lie in the practical nature of such fields in comparison to other fields like law and psychology, in which teachers and students usually follow a course book chapter by chapter. The following example shows this strategy use by the students:

(23) Asking for the future plans (Electronic engineering, 11/12/2012)

*Student: ostad, jalase baad bayad chekar konim.

(*دانشجو: استاد جلسه بعد باید چکار کنیم؟)

[‘Teacher, what shall we do next session?’]

As mentioned earlier, in Persian-speaking settings, the lecturers used both verbal and non-verbal cues to indicate the end of their lectures. Sixty-one occurrences belonged to the verbal and 39 to the non-verbal category. For the non-verbal category, Persian lecturers adopted five strategies such as looking at their watches (8, 20%), recapping their markers (10, 25%), putting their books and belongings in their bags (10, 25%), smiling and a moment of silence (6, 15%), and single clap (5, 12%). Among the non-verbal strategies, recapping the marker and gathering their belongings are the most frequent ones; the single clap was the least common type. Despite the popularity of non-verbal strategies in Iranian settings, the use of explicit verbal strategies is more common in academic lecture closings to indicate the end of the lecture.

In the Persian language, to address a second person, you can take two forms of singular and collective. These forms are to and shoma which are equivalent to tu and vous in French, respectively. Shoma which is normally used to refer to second person plural can also be used to refer to second person singular as a sign of respect or higher levels of formality. In the present study, whenever the lecturers were addressing an individual student, they used collective you through which the teacher implied higher levels of formality. They emphasized distance and separateness toward the students. We did not analyze the lecture closings regarding the students’ use of collective you since Persian culture does not allow students to address their teachers with to or singular you. This is considered as a sign of disrespect and a face threatening act. In addition, in Persian, pronouns can also be attached to the end of verbs. For instance, toon in havasetoon stands for havase shoma (‘your attention’). However, the teacher as the authority of the class can use both forms of singular and collective you to address an individual student. Collective you used by teachers to address an individual student pragmatically serves different functions. For instance, in the pre-ending stage, collective you was used by the teacher when the student was busy doing something else. Using collective you at this point is not sometimes a matter of respect, but sarcasm. To re-attract their attention, the teacher asked the distracted student a question about the content of the lecture or asked him if he was listening to the lecture. In the post-ending stage, the lecturer used collective you when addressing the individual student to guide or give him more help. In the ending stage, the lecturers did not use collective you when addressing individual students; rather, they used this type of pronoun to address the whole class. Note the following examples:

(24) Teacher: aghaye ………., bar asase bahse ma shoma begu chera in vakoneshe shimiyaiee emkan pazir nist? (Chemical engineering, 4/11/2012)

(مدرس: آقای ....... بر اساس بحث ما شما بگو چرا این واکنشه شیمیایی امکان پذیر نیست؟)

[‘Mr, …….., according to our discussion, you tell us why this chemical reaction is not possible?’]

Student: no answer

(25) Teacher: Shoma aslan gosh midi? Havasetoon be dars hast? (Psychology, 13/11/2012)

(مدرس: شما اصلا گوش میدی؟ حواستون به درس هست؟)

[Are you listening to me? Are you following the lecture?]

(26) Teacher: khanome ………, havasetoon be dars hast? (Computer engineering, 9/12/2012)

(مدرس: خانوم .......... حواستون به درس هست؟)

[‘Ms………., are you following the lecture?’]

(27) Teacher: aghaye ………. mitoonam beporsam shoma darin chekar mikonid? (Law, 9/12/2012)

(مدرس: آقای .......... میتونم بپرسم شما دارین چیکار میکنید؟)

[‘Mr. ……….. Can I ask what you are doing?’]

Collective you is the dominant form of teacher-initiated address (occurring 15 times as compared to singular address, occurring only two times) which proves that the lecturers tended to enhance the distance and the level of formality in teacher-student relationships. This finding is similar to what Schleef (2009) found in German academic settings. In his study, German academic discourse was more formal through the use of group vocatives compared to American academic settings (cf. ibd.: 1104).

This study investigated the organization, level of formality, and verbal and non-verbal ending cues in Persian academic lecture closings. Based on our observation of the level of student-teacher interactions, the analyzed data revealed that the post-ending stage occurs mostly in classes where both the lecturer and the students took an active part in the discussion, while this stage was not observed in many of the classes where the lecturer was conducting the class in monolog. Possibly, the nature of the former classes created more opportunities for students to ask their questions willingly and interact with the teacher even after the formal class hour finished.

Regarding the first research question, the results of the study indicate that Persian academic lecture closings occur in the three stages of pre-ending, ending, and post-ending. Persian-language strategies in the pre-ending stage appeared to be mostly teacher-oriented, whereas the adopted strategies of the ending stage were totally teacher-oriented. The post-ending stage presented mainly student-oriented strategies. An unexpected result is the very few occurrences of the two strategies of summarizing the key points and indicating the plan for the future despite the common guidelines in teaching resource books advising that providing summarizations at the end of lectures and drawing explicit conclusions provide students with assistance in how to relate new topics with what they have already learned as well as to what they will be learning in the future (Davis 2009: 153; Cheng 2012: 246). Indicating the plan for the future helps learners to know what they are expected to learn and to perform during and at the end of the semester. Having the lesson plan in their minds, they are prone to become more self-regulated and disciplined in their study schedules.

Obviously, speech brings to the surface the social structural differences. Comparing the findings of this study with Cheng’s (2012) study of English lecture closings revealed some similarities and differences in the rhetorical structure of academic lecture closings. The two discourse settings share the teachers strategies of Indicating the end of a lecture, Asking if students have questions, Answering students questions, Calling for attention, Explaining course-related issues, Dismissing the class or Leave-taking goodbyes and wishes, Indicating the plan for the future, Raising questions for discussion, and Summarizing the key points, though with different ranks and frequencies. Aside from the above-mentioned similarities, Persian and Cheng’s (2012) English settings showed some differences. For instance, coming to a conclusion of content and explaining non-course related issues are the unique strategies in English academic closings (cf. Cheng: 2012: 238). In contrast, in the Persian-speaking settings of the present study, the lecturer did not usually explain non-course related issues unless the students traced them. Asking students about the remaining time is the observed Persian-specific strategy which was not reported by Cheng (2012). As we discussed earlier, using this strategy does not necessarily mean that the teacher was not aware of the time; rather, sometimes it was used by him to implicitly signal the last moments of the class.

Messages can clearly be conveyed both verbally and non-verbally. Wordless cues can sometimes substitute the whole utterance. Considering this fact, the Persian-language lecturers used not only verbal but also non-verbal cues to indicate the end of the lecture, though verbal cues exceeded the non-verbal ones.

The analysis of data regarding the third research question revealed that by using collective you as a sign of formal address, the lecturers in Persian academic settings tended to emphasize teacher-student distance. This formality adopted by Persian academic lecturers in classroom interaction was also reported by Schleef (2009) in German settings.

As it was pointed out by Lee (2009), being a kind of real-time discourse, the structure of lecture closings enjoys flexibility. Thus, the findings of this study cannot be prescribed and generalized to all academic discourse communities. However, the purpose of genre analysis is not to provide prescriptions but to identify the generic structures that tend to recur (cf. Swales: 1990). Individual teaching styles are always an important factor in how teachers tend to conduct their classes. There are other contextual variables beyond those addressed in this study such as discipline, the lecturer’s gender, the level of lecturer experience, the level of student’s participation, interactive and monolog classes, which may be considered for future studies. The findings can provide practical applications for prospective and novice lecturers informing them of the organization features of lecture closings and the level of formality. Moreover, students may also make use of their awareness of lecturer strategies to elevate their understanding of the lecture as well as their relationship with the lecturer.

Adel, Annelie (2010): “Just to give you kind of a map of where we are going: A taxonomy of metadiscourse in spoken and written academic English”. Nordic Journal of English Studies 9/2: 69–97.

Allison, Desmond/Tauroza, Steve (1995): “The effect of discourse organization on lecture comprehension”. English for Specific Purposes 14/2: 157–173.

Camiciottoli, Crawford B. (2004): “Interactive discourse structuring in L2 guest lectures: Some insights from a comparative corpus-based study”. Journal of English for Academic Purposes 3/1: 39–54.

Chaudron, Craig/Richards, Jack C. (1986): “The effect of discourse markers on the comprehension of lectures”. Applied Linguistics 7/2: 113–127.

Cheng, Stephanie W. (2012): “‘That’s it for today’: Academic lecture closings and the impact of class size”. English for Specific Purposes 31: 234–248.

Davis, Barbara G. (2009): Tools for teaching. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Deroey, Katrien/Taverniers Miriam (2012): “‘Ignore that cause it’s totally irrelevant’: Marking lesser relevance in lectures”. Journal of Pragmatics 44/14: 2085–2099.

Dudley-Evans, Tony (1994): “Variations in the discourse patterns favored by different disciplines and the pedagogical implications”. In: Flowerdew, John (ed.): Academic listening: Research perspectives. New York, Cambridge University Press: 146–158.

Fan, Fan Akpan (2012): “Teacher: students’ interpersonal relationships and students’ academic achievements in social studies”. Teacher and Teaching: Theory and Practice 18/4: 483–490.

Ferris, Dana/Tagg, Tracy (1996): “Academic oral communication needs of EAP learners: What subject-matter instructors actually require”. TESOL Quarterly 30/1: 31–58.

Flowerdew, John/Miller, Lindsay (1997): “The teaching of academic listening comprehension and the question of authenticity”. English for Specific Purposes 16/1: 27–46.

Fortanet, Immaculata (2004): “The use of ‘we’ in university lectures: Reference and function”. English for Specific Purposes 23/1: 45–66.

Hawkins, Abigail/Barbour, Michael K./Graham, Charles A. (2010): “Teacher student interaction and academic performance at Utah’s electronic high school”. Unpublished paper presented at the 26th Annual Conference on Distance Teaching/Learning.

Jordan, Roberto R. (1997): English for academic purposes: A guide and resource book for teachers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jung, Euen H. (2006): “Misunderstanding of academic monologues by nonnative speakers of English”. Journal of Pragmatics 38: 1928–1942.

Jung, Euen H. (2003): “The effects of organization markers on ESL learners’ text understanding”. TESOL Quarterly 37/4: 749–759.

Kashiha, Hadi/Heng, Chan S. (2014): “Structural analysis of lexical bundles in University lectures of Politics and Chemistry”. International Journal of Applied Linguistics/English literature 3/1: 224–230.

Lee, Josheph J. (2009): “Size matters: An exploratory comparison of small- and large-class university lecture introductions". English for Specific Purposes 28/1: 42–57.

Morell, Teresa (2007): “What enhances EFL students’ participation in lecture discourse? Student, lecturer and discourse perspectives”. Journal of English for Academic Purposes 6/3: 222–237.

Morell, Teresa (2004): “Interactive lecture discourse for university EFL students”. English for Specific Purposes 23/3: 325–338.

Schleef, Erik (2009): “A cross-cultural investigation of German and American academic style”. Journal of Pragmatics 41/6: 1104–1124.

Simpson-Vlach, Rita/Ellis, Nick C. (2010): “An academic formulas list: New methods in phraseology research”. Applied Linguistics 31/4: 487–512.

Strodt-Lopez, Barbara (1991): “Tying it all in: Asides in university lectures”. Applied Linguistics 2/2: 117–140.

Swales, John M. (1990): Genre analysis: English in academic and research settings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Swales, John M. (2004): Research genres: Explorations and applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Thompson, Susan (1994): “Frameworks and contexts: A genre-based approach to analyzing lecture introductions”. English for Specific Purposes 13/2: 171–186.

Thompson, Susan E. (2003): “Text-structuring metadiscourse, intonation and the signaling of organisation in academic lectures”. Journal of English for Academic Purposes 2/1: 5–20.

Young, Lynne (1994): “University lectures: Macro-structure and micro-features”. In: Flowerdew, John (ed.): Academic listening: Research perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: 159–176.