http://dx.doi.org/10.13092/lo.75.2517

Because, as the saying goes, “a picture is worth a thousand words”, the image below (image 1), taken from a widely read publication, superbly encapsulates the aim of this paper, that is, how eating disorders are, more often than not, promoted in the written media by means of animal metaphors which tend to be illustrated by photographs showing a connection between females and food.

Image 1: National Enquirer, March 2012: Front page

As can be seen, the front cover of the magazine features actress Kirstie Alley, who has been outspoken with her struggle regarding weight issues. Her apparently inability to control her appetite is linguistically rendered through an animal-based metaphor (i. e. "pigging out”) which is visually reinforced by several photographs of the actress eating food. Metaphors like the one above, far from being isolated figurative usages, have become essential ingredients in media discourse when dealing with the concoction women and food. As a matter of fact, as the following pages will try to show, animal metaphors are always at hand in the written press in order to sanction eating behaviors in females.

The representation of women in the media has received a great deal of attention and critics have analyzed different strategies used in the transmission of negative views of womanhood (cf. Tuchman 1979; Gough-Yates 2003). From explicit cartoons presenting women as chatterboxes (cf. Talbot 2003: 469) to stereotypical portrayals of women as wives, mothers and sex objects (cf. Demarest/Garner 1992) through more sophisticated techniques of transitivity choices underlying the assumption that the role of women is one of subservience (cf. Vetterling-Braggin 1981; Calvo 1998), color associations that simply reinforce the division of the sexes (cf. Calvo 1998), discourse strategies (cf. Peirce 1990; Talbot 1995; Stoll 1998) and metaphorical identifications (cf. Mills 1995: 137), gender discrimination in the press comes clad in many different cloaks.

This paper looks at animal-based metaphors used by the written media in order to convey negative messages about the relationship between women and food. By analyzing a corpus of metaphors extracted from different sorts of publications,1 which include newspapers and magazines, this article tries to shed some light on how such figurative usages together with their visual representation may contribute to women's body dissatisfaction, thin ideal internalization and disordered eating.

Without entering into the numerous and sometimes even conflicting views on metaphor, the present study focuses on metaphor as a mechanism enabling the language user to talk about one thing in terms of another and on its potential to clothe or disguise the message in order to unveil the true assumptions that unveil the use of such linguistic products. In addition to adopting a cognitive approach to figurative language, the social dimension of metaphor in people’s understanding of the world and of themselves together with the pivotal role language plays as a channel through which ideas and beliefs are transmitted and perpetuated (cf. Sperber 1996; Saville-Troike 2003) will be taken into account in the present analysis to explore how the pervasiveness of such animal metaphors may have detrimental effects on females.

Despite the fact that this study does not focus on how readers feel or think when they are the agent or the target of such animal metaphors – although it could be a powerful area for future empirical research – this article does hope to bring to the surface how eating disorders are very often promoted by means of metaphors based on animals.

First, the paper will offer a brief introduction to Conceptual Metaphor Theory (henceforth CMT) since it will provide the analytical tools to unravel the motivations that have given way to the metaphors under study (3). The next section will focus on the folk cognitive model known as The Great Chain of Being (4), which will serve as a framework to understand how the use of animal-related metaphors frequently conveys negative views about women. This will be followed by an overview of the generic PEOPLE ARE ANIMALS metaphor (5) with a special focus on the issue of control underlying most linguistic instantiations of such a metaphor (6). Later on, a global classification of linguistic fauna from different disciplines will be provided (7). After that, several examples taken from publications will illustrate one of the most common conceptualizations of HUNGER AS AN ANIMAL metaphor (8). The next part will offer an analysis of the corpus of animal-based metaphors gathered for this research (9). Finally, the paper ends with a brief discussion of how such metaphors may have a negative effect on women´s perception of their own bodies. Special attention will be paid to the power of metaphor in the construction of identity. Last but not least, some conclusions will be drawn regarding the connection between women, food and animal metaphors (10).

Far from the traditional view which regards metaphor as a mere linguistic device in which a word or phrase literally denoting one idea is used in place of another usually for the figurative embellishment of otherwise straightforward language (cf. Ortony 1993; Gibbs 1994; Lakoff/Johnson 1980), the present study adopts a cognitive approach whereby metaphors are seen as integral mechanisms of human thinking that are both cognitively as well as culturally motivated (cf. Kövecses 2006).

A pivotal distinction, then, is made between conceptual and linguistic metaphors. The former belong to the level of thought and constitute a small group of mental schemas whereby the human mind understands abstract concepts in terms of more concrete, bodily experiences; the latter, on the other hand, are the surface manifestation in language of conceptual metaphor. From this perspective, metaphor is defined as a systematic set of correspondences or mappings between two conceptual domains of experience, where one of the domains (called “the source”) enables us to structure, understand and make sense of another experiential domain (called “the target”) (cf. Lakoff/Turner 1989; Lakoff/Johnson 1980; Barcelona 2003; Dirven/Pörings 2002).

Consider, for example, for the sake of this paper, how people often resort to animals in order to make sense of an array of different concepts such a business, immigration and emotions. In the field of economy the working of the financial system and the intricacies of the business world are frequently understood in terms of animals (cf. Silaški 2009; Silaški/Durovic 2010). Human participants may include fat cats (i. e. ‘top executives’),hawks (i. e. ‘economic policy advisors who monitor and control inflation’), sharks (i. e. ‘someone interested in taking over a firm’) or pigs (i. e. ‘greedy investors’). Besides, it is not only people but also markets, companies and products that are categorized as animals of some sort. So, for example, the fluctuations of the market run parallel to animal movements: a stagnant market is called a deer market whereas a market with a downward and upward trend is labelled as a bear and bull market respectively. Similarly, according to its size and power, companies can be classified into several species, such as gorillas, gazelles or turkeys, depending on whether they are big, fast-growing or start-ups. Even products themselves are known as cash cow (i. e. ‘well-known products which produce revenues’), golden goose (i. e. ‘profitable products’) and turkey (i. e. ‘a poor investment’) (cf. Silaški 2009: 62).

Metaphors used to construct the debate over immigration frequently involve animal imagery. Those fleeing away to other countries tend to be represented either as dangerous beasts that pose a threat to homeland security for they can attack and, therefore, need to be exterminated (i. e. baited, hunted, eaten) or as beasts of burden which can be exploited for work and food (e. g.: dogs, donkeys, pigs). In fact, even massive human migratory movements are projected onto different groups of animals such as packs, hordes or swarms and animal motions (e. g.: creep, crawl, fly). Similar considerations apply to the poor conditions in which immigrants are generally transported into new places as well as to the measures to be taken in the construction of border fences. Figurative usages of livestock, cage or kennel pervade immigration policies, equating immigrants with animals (cf. Santa Ana 1999: 190–195; O’Brien 2003: 45–47).

The wide repertoire of emotions is likewise captured in language through animals. Whether it is anger, jealousy, envy, happiness or love, feelings are seen as wild beasts trying to break free from the control of the rational human being (cf. Kövecses 2005). After all, as will be seen later on, animals stand out for their instinctual behavior as opposed to the more rational person, which accounts for the figurative usage of animal names when dealing with passions. Anger, for instance, is depicted as a sleeping animal that is dangerous to awaken (e. g.: to awaken someone’s ire, to arouse somebody’s anger) and, therefore, needs to be kept at bay (e. g.: to tame someone’s temper). Sometimes such a passion is transformed into a horse (e. g.: to curb someone’s anger, unbridled rage, to rein in someone’s temper) or a snake (e. g.: to hiss, venomous attack, squirm with suppressed rage). Jealousy and envy, by contrast, find their way into language mainly in the guise of insects (e. g.: the buzz of jealousy, jealousy stings like a wasp, bitten by envy) whereas happiness and love tend to be regarded as captive animals (e. g.: joy breaks loose, let go off someone’s feelings, to unleash someone’s love) (cf. Kövecses 2005: 12).

It seems obvious, then, that animals pervade human speech and thought, conveying a multiplicity of meanings. Such metaphorical usages of animals are not random or isolated linguistic products, but, on the contrary, they form coherent systems of thought enabling people to come to terms with their experiences. The previous animal-related metaphors found in language, therefore, are simply the surface manifestation of the conceptual metaphors BUSINESSES ARE ANIMALS (cf. Silaški/Durovic 2010: 57), IMMIGRANTS ARE ANIMALS (Santa Ana 1999: 196), EMOTIONS ARE ANIMALS (cf. Kövecses 2003: 311), that is, cognitive mechanisms which enable people to reason about businesses, immigration and emotions in terms of the animal kingdom. Such metaphorical thinking, according to CMT, seems to be grounded in embodied experience, that is, in the relationship that people establish with the world through their bodies. This notion of embodiment is definitely the basic ingredient within CMT to support the mental nature as well as the universality of conceptual metaphor.2

Needless to say, people’s experience with animals can be traced back to virtually the dawn of times since the survival of the human race largely depended on their knowledge of the natural world. Being able to identify which species were dangerous, had healing properties, could destroy the crops or provided nourishment must have been of vital use for people. It is not surprising, then, that people have always resorted to animals as a way of explaining human behavior, human feelings and even human relations (cf. Kövecses 2003: 311). In this regard, to put it in Song’s (2009: 10) words, “the colorful animal kingdom is closely linked with our life and the relationship between humans and animals makes people familiar with the habits of animals”.

Not surprisingly, then, animal metaphors are one of the richest sources for figurative representation of multifarious world phenomena found in probably all languages in the world. Apart from serving as a bridge to make sense of people, both physically and psychologically speaking, animals have become powerful cognitive tools in the conceptualization of social relations (cf. Baker 1981; Fraser 1981; Baider/Gesuato 2005) communication (cf. Musolff/MacArthur/Pagani 2014), emotions (cf. Sánchez/Chamizo 2000), politics (cf. Carver/Pikalo 2008), terrorism (cf. Hellín 2008), business (cf. Silaški/Durovic 2010), illnesses (cf. Sontag 1989), sports (cf. Silaski 2009), immigration (cf. Santa Ana 1999) or religion (cf. Thornton 1989), among many other issues.

Yet, even though there is a widespread tendency to conceptualize different realms of experience in the guise of animals, the instantiation of the mapping varies considerably across different language-speaking communities (cf. Deignan 2003: 255; Kövecses 2005: 20). Cross-linguistic studies have shed some light on how animal metaphors differ significantly given different cultural scenarios. The very same animal name can have different values depending on the language. In Malay a goat denotes a coward, but in English it refers to someone who is blamed for a loss or failure and in Spanish to someone who acts in a crazy way. Besides, if the figurative meaning of such an animal name were to be looked up in an Arabic and Russian dictionary the senses of someone gullible and stubborn would be found respectively (cf. Deignan 2003: 262).

Besides, even though the conceptual metaphor PEOPLE ARE ANIMALS seems to underlie most languages, and, therefore, to be universal, some indigenous languages do not differentiate between the categories of people and animals, so that there is not such a metaphor given that for these communities both source and target domains are conflated (cf. Leezenberg 2001: 15; Durkheim/Mauss 1963: 6–7).

The values attached to animals do vary depending on the context, understood in its broadest sense (individual, social, regional, ethnic, cultural, social, diachronic or synchronic) and, therefore, shape metaphorical conceptualization.3 Hence, even though embodiment provides the basis for conceptual metaphors, all the elements that physical experiences entail will not be used in the creation of linguistic metaphors, but, on the contrary, only a few will be singled out by each group of people depending on the context or on what Kövecses (2005: 8) terms “differential experiential focus”. Metaphors, then, are partly universal, partly context-specific, and, as will be seen later on, this is glaringly obvious in the field of animal metaphors given that because of geographic, religious, social or cultural reasons some animals will be preferred over others in the conceptualization of eating behaviors.

To whet your appetite, for instance, consider how the notion of happiness is viewed in animalistic behavior metaphors in several languages:to be as happy as a pig in slop in English, más feliz que una perdiz (literally ‘happier than a partridge’) in Spanish or the Persian mesle xær keif mikone (literally ‘like a donkey he is enjoying himself”) (cf. Kövecses 2005: 98). Yet, despite the fact that the three language communities conceptualize people who are happy as an animal that lives well, the choice of the animal is completely different for it is a pig, a partridge and a donkey, and certainly reflects those cultures. It goes without saying that the mechanism of zoosemy mirrors closely the ways of thinking and the cultural peculiarities of particular societies.

As a corollary, as opposed to the traditional or classical view of metaphor as a rhetorical artifact, this paper adopts the aforementioned cognitive approach in the analysis of animal-related metaphors applied to the relationship between women with their eating habits.

Before dealing with some of the most common animal metaphors pervading the media when establishing a connection between females with food, it is necessary to discuss a folk cognitive model known as “The Great Chain of Being” (cf. Lovejoy 1936; Tilyard 1959; Lakoff/Turner 1989) because of its influence and repercussion in our understanding of the universe, of the human being and of language itself.

Briefly put, the major premise of THE GREAT CHAIN OF BEING is that every existing thing in the universe has its place in a divinely planned hierarchical order which is pictured as a chain vertically extended, and the place of beings and objects depends on their properties and behavior, that is, the more complex the being, the higher it stands.4 So at the bottom stand various types of inanimate objects, such as metals, stones and the four elements, defined by their structural and functional properties and behavior. Higher up are various members of the vegetable class, like flowers and plants, with their biological functions and attributes. Then come animals, which are defined by their instinctual characteristics and behavior. Afterwards, human beings, who possess higher order attributes and behavior and, finally, celestial creatures with their supernatural traits and powers. Within each level there are sub-levels defined by different degrees of complexity and power in relation to each other (i. e. within the animal realm the lion is above the rabbit, which, in turn, is above the worm). This hierarchical organization, then, presupposes that the natural order of the cosmos is that higher forms of existence dominate lower forms of existence.

The GREAT CHAIN OF BEING metaphor accommodates two types of conceptual mappings which enable us to see the chain as a top-down hierarchy in which higher-level attributes and behavior are conceptualized in terms of lower-level attributes and behavior as well as a bottom-up hierarchy in which lower-level attributes and behavior are understood in terms of higher-level attributes and behavior. Hence, adopting a top-down approach, human beings can be understood via the instinctual and functional attributes and behavior of animals, plants and lower substances (e. g. she is a pig, she is a rose, she is a diamond) or, on the contrary, from a bottom-up perspective, people can be conceptualized through the divine qualities of supernatural creatures (e. g. she is an angel, she is a goddess, she is a siren).

The cultural framework provided by THE GREAT CHAIN OF BEING constitutes the bedrock for the present analysis for, in general terms, when people are equated with animals—or other lower substances—not only are instinctual and functional qualities or behavior being highlighted, but because humans are conceptualized in the guise of lower forms of existence, the identification is likely to convey a negative evaluation. On the contrary, when people are equated with supernatural creatures, the shift upwards in the chain tends to endow the metaphorical identification with positive evaluations (cf. Lakoff/Turner 1989: 170–180).

Interestingly, as will be seen later on, the cocktail women with food is frequently cooked up in the media by means of animal metaphors. Despite the fact that eating is a vital need for all living creatures, the general negative import attached to animal metaphors will imply a negative connection between females with food, with the fatal consequences this could have on women’s physical as well as mental health.

Figurative expressions drawing on the source domain of animals abound in English and people are frequently conceptualized as animals of some sort. The appearance, sex, behavior, habitat, living conditions and even the sounds emitted by animals have become common grounds for the understanding of the human being (cf. Goatly 2006: 15–17; Shephard 1996: 25).

Salient physical characteristics of animals are typically projected onto people (cf. Ruiz/Herrero 2006). Hence, the human zoo includes giraffes andducks for tall and short people, respectively; cows and snakes depending on whether the person is fat or thin and oxen and chickens for the strong and the weak. As far as age is concerned, mature people and younger individuals find their equivalent in the relation parent/offspring of several animals. Consider, for instance, the terms hen/chick or bear/cub to refer to middle-aged and young women and men (cf. Fernández/Catalán 2003: 780).

In like manner, gender is marked through different animals. Aside from the obvious biological differences between male and female animals and their corresponding application to men and women (e. g.: rooster/hen, bull/cow, fox/vixen), homosexuality is also conveyed by means of the figurative use of names of beasts. In this case, the reversal of the sexes is to be expected; in other words, male animals tend to be applied to lesbians (e. g.: bulls) whereas female ones to gay men (e. g.: pussycat) (cf. López-Rodríguez 2007: 38).

More subjective values regarding intelligence or beauty, for example, are likewise attributed to animals. Needless to say, in such cases cultural views play a pivotal role in the encoding of the metaphor. Within bird species owls are regarded in many cultures as wise as opposed to turkeys, dodos or cuckoos, which account for their figurative senses to denote smart and stupid individuals. Similarly, the figurative uses of dog and coyote may apply to both ugly men and women whereas attractiveness is suggested in the metaphorical sense of vixen (‘sexy female’) and stud (‘sexy male’) (cf. Kövecses 2005: 57).

The appearance of the body part of an animal can also be transferred to humans. Virtually from head to toe the human body can be metamorphosed into an animal. Hairstyles may come into pigtails (‘a short, tight braid of hair)’, pony-tails (‘a longer, loose bunch of hair tied up’) ormanes (‘long hair’) (cf. Esenova 2013: 48–50). There are dragon heads and horse faces, cat’s and puppy’s eyes,crow’s feet around the eyes but fish eyes on the toes; piggy noses, mosquito bites (i. e. ‘small breasts’) and waspwaists along with goose bumps, not to mention all those animals euphemistically standing for the genitalia, like sharks (‘penis’), camel toe (‘vagina’) and, particularly, the furry ones (i. e. rabbit, beaver, ferret, cat, pussy) (cf. Sommer/Sommer 2011: 238–241).

People can also be conceptualized in the guise of animals based on the observation of their behavior. Patterns of conduct have been identified in animals given similar conditions. Ostriches have a tendency to hide their head when in danger as to avoid problems, just like chicks look for shelter and protection under a hen’s wings when sensing danger. Such prototypical actions performed by these animals have paved the way for their figurative uses to refer to people who avoid facts or run away from difficult, risky situations (cf. Deignan 2003: 255).

In addition to nominal instances like the ones above, animal-based metaphors may exhibit different grammatical functions, like verbs and adjectives (cf. Ruiz/Herrero 2005: 932–935). A certain action will typically be ascribed to an animal and then metaphorically extrapolated to people, such as following to dogs, hoarding to squirrels, repeating to parrots, devouring to wolves or bothering to bugs. There are also adjectives galore based on animals. Human behavior can be described as catty (‘spiteful’), bitchy (‘unpleasant’), ratty (‘despicable’), wolfish (‘machiavellian’) or sheepish (‘timid or stupid’), just to number some of the endless possibilities borrowed from the animal kingdom (cf. Sommer/Sommer 2011: 241).

In some instances, rather than the animal name itself standing for a particular ability (or lack of it), an entire fixed expression containing the name of the beast is used (cf. Ruiz/Herrero 2005: 935). Common examples include to have hawk’s eyes (‘outstanding eyesight’), to have an elephant’s mind (‘great memory’) or to have a bird brain (‘lack of intellect’). On other occasions the metaphor is not derived from an animal name per se but rather specific actions of the animals are singled out and ascribed to humans. This is the case, for instance, of to leave with one’s tail between one’s legs, which stems from the fact that when a dog runs away from something in fear, usually after a fight, it will tuck its tail between its rear legs so its tail cannot get bitten off. Therefore, when applied to humans, the action metaphorically mirrors the dog’s behavior since it refers to a person who is defeated and humiliated, usually after having lost an argument, and is backing away. A similar rationale can be gleaned out in to stand/get up on one’s hind legs. Originally belonging to the equestrian semantic field, its figurative application to someone who gets angry and assertive and might stand up in order to argue evokes the animal scenario of a horse energetically rearing up as if to attack.

The habitat of an animal can also map to the human target domain in order to indicate that the person referred to lives in a similar way. Certainly, the living conditions of an animal vary considerably depending on whether they are pets, livestock or wild. In fact, whereas the former basically co-exist with humans and are kept either to keep company or to be exploited or eaten, not only do the latter live in the wilderness, but they also enjoy freedom and no restraint. Hence, it is not surprising that in the encoding of the animal-related metaphor such features are transferred onto the human domain. So the privileged position of pets finds its way into language, for the very word pet is used as a term of endearment. In a similar fashion, the tendency to categorize women as farmyard animals such as hens, chickens, cows, heifers, mares, fillies or nags, as opposed to men, who are often seen as wild beasts like bulls, oxen, foxes, tigers, lions or lynxes seems to hint at the notion of domesticity and servitude instilled by patriarchy (see López-Rodríguez 2007: 39–42). By the same token, as already mentioned, society’s views on immigrants may be grounded, to a large extent, on the living conditions of certain animals. As a matter of fact, when thinking of the conditions in which many immigrants tend to be smuggled into a country, that is, squashed and hidden in tiny spaces, it comes as no surprise that they may be conceptualized as chickens for these animals are raised in tiny spaces deprived of movement to speed the process of gaining weight and are practically undistinguishable (cf. Santa Ana 1999: 193–197).

An important source of nourishment, animal-derived metaphors can also reveal significant aspects regarding the culture of a place and its people. As a matter of fact, not only do the gastronomy, history and traditions surface when dealing with animals which end up in our stomachs, but nationalistic sentiments are also brought to the fore since what for some cultures is a delicacy (e. g. frogs for the French), for others it may be an object of revulsion (e. g. Koreans eat dogs) and even a sin (e. g. pork is forbidden in the Muslim and Jewish communities and cows are sacred for the Hindi). In this sense, prejudices against others appear to be interwoven in those animal metaphors that are part of the diet of a group (see López-Rodríguez 2014: 7–11). Suffice it to say that frogs, roast beefs, dog-eaters or cows may be used as insults for the French, the English, the Koreans and the Hindi (Harris 1985: xii).

Animal metaphors extend to some sounds. Despite the fact that not all animals are ascribed sounds in English, many do. Common onomatopoeias include meow for the cat, woof for the dog, moo for the cow, cock-a-doodle-doo for the rooster or oink for the pig. When directed at one person, the salient characteristics of the animal that makes the sound are being highlighted (cf. Ruiz/Herrero 2005: 937). In addition, there is a wide repertoire of speech verbs that stem from sounds typically emitted by animals. Bark, bellow, howl, roar or snarl, to mention a few, are commonly applied to humans.

Such speech verbs are particularly interesting when analyzed in the light of Pragmatics owing to their illocutionary force. In this regard it is worth remembering Austin’s speech act theory which, briefly put, states that almost any speech act consists of three components, namely, the locutionary act (i. e. actual utterance), the illocutionary act or illocutionary force of the utterance (i. e. the intended significance) and, finally, the perlocutionary act (i. e. the actual effect of the utterance on the person referred to). In the case of animal-based metaphors the illocutionary force is relevant because the animal scenario is brought to the fore by highlighting one of the main differences between beast and people which is human language. Indeed, despite the fact that animals do communicate in a variety of ways, human language has got certain properties which makes it unique and different from animal communication systems since it is flexible, creative and more elaborate. Interestingly, most animal sound verbs are tinged with pejorative connotations since they appear to highlight the brutish side of people. For instance, the sense of the verb ‘to order’ may find an animal equivalent in roar (lion), bellow (bull) or howl (dog/wolf) whereas ‘to make a continuous sound’ in buzz and hum (flying insects). Certainly, the connotations that stem from the animal sound verbs reinforce the aggressiveness typical of some animals in the former and the sensation of annoyance in the latter (cf. Ruiz/Herrero 2005: 933).

More often than not, the use of animal metaphors is associated with semantic derogation, understood as the use of a word to convey negative connotations (cf. Talebinejad/Dastjerdi 2005: 133). Animals have indeed become common vehicles to express undesirable human characteristics and the list of terms of deep contempt include diverse species such as reptiles (e. g.: a snake = ‘a deceitful and unprincipled person’), mammals (e. g.: a donkey = ‘a blockhead or fool’), amphibians (e. g.: a toad = ‘an unpleasant person’), crustaceans (e. g.: a crab = ‘an ill-tempered person’), birds (e. g.: a turkey = ‘a person who lacks common sense’), rodents (e. g.: a rat = ‘a despised person’), fish (e. g.: shark = ‘a rapacious crafty person who takes advantage of others often through usury, extortion, or devious means’) or insects (e. g.: a bug = ‘a person judged to be legally or medically insane’) (cf. Sommer/Sommer 2011: 241).

Such uncomplimentary meanings are certainly in tune with the hierarchical organization of THE GREAT CHAIN OF BEING, where humans stand above animals and, therefore, by conceptualizing people as animals, the former are lowered both physically and figuratively speaking. Most animal metaphors are derogatory in nature since they reduce people to the category of the non-human. In fact, the semantic process of zoosemy brings to the fore the dichotomy human versus animal, even though, from a strictly biological point of view, humans themselves are higher-level animals. In this regard, as Lévi-Strauss (1968: 26) claimed, animal metaphors help humans address this duality of being a part of nature yet at the same time somehow removed from and above it.

So being animals, humans need to differentiate themselves from other beasts by appealing to their rational capacity. In other words, as opposed to the instinctual animal, humans can control their innate impulses thanks to their intellectual superiority. As a matter of fact, the rationale for the PEOPLE ARE ANIMALS metaphor seems to hint at the notion that within the binary opposition human/animal what distinguishes the former from the latter is their rational capacity, in other words, their ability to control their behavior. According to this dichotomy, there is an animal inside each person and civilized people are expected to restrain their animal instincts, letting their rational side rule over them. The metaphors HUMAN BEHAVIOR IS ANIMAL BEHAVIOR (Kövecses 1988: 32), ANGER IS ANIMAL BEHAVIOR (Nayak/Gibbs 1990: 316), PASSIONS ARE BEASTS INSIDE US (Kövecses 1988: 32), A LUSTFUL PERSON IS AN ANIMAL (Lakoff 1987: 75) or CONTROL OF AN UNPREDICTABLE/UNDESIRABLE FORCE IS A RIDER´S CONTROL OF A HORSE (MacArthur 2005: 71), to name just a few, conceptualize extreme behavior and, therefore, lack of control, by resorting to a common scenario: the animal kingdom.

This notion of control or rather lack of control is certainly seen at work in countless animal metaphors. There is indeed a wide range of terms targeted at people that cannot refrain their instincts: hunger (e. g.: wolf), laughter (e. g.: hyena), sexual desire (e. g.: tiger), bodily functions (e. g.: pig) or anger (e. g.: beast). In addition, lack of self-control not only reduces people to the category of animals but it also excludes them from society since they do not adhere to conventional norms. As a matter of fact, animal metaphors fall within the scope of the so-called “control metaphors” (cf. Pérez Rull 2001: 180; MacArthur 2005: 91–92), that is to say, powerful mechanisms that help in the regulation of people’s conduct according to the set of rules or the code dictated by society.

In this sense, animal metaphors can exert control in two different ways. On the cognitive level, they accentuate the difference between human and bestial behavior and in this way encourage people to conform to socially approved codes. On the social level, animal metaphors provide people with social etiquettes to increase or reduce social distance (cf. Brandes 1984: 207). By means of illustration consider the figurative use of wolf to refer to a man who is direct and zealous in amatory attentions to women. Not only does such an animalistic portrayal emphasize the bestial side of man by appealing to the primary sexual instinct but it also labels him as a potential danger or threat to women for he is a predator looking for his prey.

This twofold dimension condensed in animal terms must be borne in mind in the present analysis for, as will be seen, women are encouraged to control their appetite in order to conform to the unattainable canons of beauty imposed by society. Failure to comply with society’s expectations regarding attractiveness results in the degradation of women to the animal kingdom. As a corollary, the pages of magazines are rife with animal images that either mock women who are not slim or threaten those who indulge in food, do not stick to a strict diet and exercise routine.

Not surprisingly, as the following section will show, the use of animal metaphors in articles dealing with the relationship between women with food does bring to the surface the notion of control underlying most figurative usages of animal names. After all, virtually all the articles encountered in the course of this research deal with dieting, which basically consists of suppressing one’s hunger, the most basic instinct in all living species. Lack of control when it comes to food intake takes the form of an animal and, therefore, flicking through the pages of magazines and newspapers one often encounters a host of metaphors presenting women as cows, pigs, whales and verbal instances of animal terms like pig out or wolf down.

Aside from the linguistic derogation that such animal terms convey, the fact that they tend to be accompanied by a visual component (i. e. photographs of women eating or surrounded by food) could reinforce the negative connection forged between women, food and the animal metaphor. After all, if one thinks of the linguistic sign in Saussure's view, that is, consisting of a signifier (the shape of the word), a signified (the ideational component or object that appears in our minds) and the referent (the actual object in the real world), the use of illustrations appears to serve as the signified itself.

Within the macro category ANIMALS several classifications have been outlined in order to shed some light onto the conceptualization of people as animals. Traditional folk taxonomy classifies animals primarily according to their physical space position, expressed by the features land, air and water, and assigns each species distinct features connected with their loci mainly within the realm of symbolic meanings (cf. Martsa 1999: 73–77; Sax 2001: 34–42). So according to folklore and mythology air creatures are connected to the heavens, where deities dwell, and therefore they are believed to herald our desires to the very gods in the skies. Not surprisingly, then, there are plenty of bird names linked to freedom (e. g.: eagle), power (e. g.: hawk) and wisdom (e. g.: owl) (cf. Halupka-Rešetar 2003: 1893–1897; Goatly 2006: 15–22).

Sociological studies turn their attention to social space position. Such a categorization mirrors the social discrimination human beings practice on a daily basis, which basically consists of sorting people into the categories of those who are “like us” and those who are “not like us” (i. e. the well-known difference between “the self” vs. “the other”) and extrapolate this binary opposition to the animal kingdom (cf. Shepard 1996: 20–46). So within society family members are the closest, followed by friends, acquaintances and finally strangers. These distinctions are then treated as analogies in the non-human world, for we have pets (virtually family members), livestock or farm (closer to people) and wild animals (removed from people). This may certainly account for the favorable connotations attached to the very word pet, a term of endearment, as opposed to the negative ones of farmyard (e. g.: cow) and wild animals (e. g.: wolf) (cf. Leach 1964: 25–58).

Anthropological studies have refined the taxonomy of animals based on social distance by bringing the criteria of edibility and taboo to the forefront (cf. Leach 1964). So, along with closeness to people, cultural and religious attitudes attached to the culinary preferences of different communities are taken into account in order to explain the pejorative or positive attitudes attached to certain animal names. Conspicuous examples that come up to one’s mind include the pig and the frog. The former is a forbidden animal within the Jewish and Muslim communities, and its figurative meaning refers to a dirty or gluttonous individual. The latter is regarded as a delicacy for the French and as an object of revulsion for the British, which explains why it is used as an insult for that nationality (cf. Harris 1985: v-xii).

More recently, within the field of socio-linguistics, gender-oriented analyses have drawn attention to the imbalance found in animal pairs (Baker 1981; Hines 1999a, 1999b; Baider/Gesuato 2003; Fernández/Catalán 2003; Brennan 2005). Studies have shown a clear bias against the female sex. In fact, more often than not, the male species appears to be tinged with favorable overtones as opposed to the female one. Consider, for example, hen (‘a fussy middle-aged woman’) versus rooster (‘a conceited man’), fox (‘a clever individual’) as opposed to vixen ‘(a sexually active woman’) and, of course, dog (‘a lazy, even worthless person’) as opposed to the largely taboo bitch (‘a spiteful or immoral woman’). In addition, patriarchal attitudes towards the role of women seem to be embedded in certain animal terms given the preference for small and domestic animals in the conceptualization of females (e. g.: chick, bunny, kitten).

Finally, within the same discipline, studies on ethnicity and race have pointed out how racist attitudes towards different peoples are frequently channeled through the use of animal metaphors (cf. Brandes 1984; Halupka-Rešetar 2003; Goatly 2006; Carver/Pikalo 2008). As a matter of fact, oppression and inferiority tend to be justified by resorting to different creatures. Names of apes are always at hand to disparage the blacks, implying lack of evolution within Darwin’s theories (e. g.: monkey, gorilla). Similarly, animalistic images pervade the discourse of immigration since foreigners are often perceived as menacing animals (e. g.: plagues) or as beasts of burden (e. g.: donkeys).

Animal metaphors, needless to say, are multi-faceted. They can be analyzed from different points of view which can certainly enrich the understanding of their figurative senses. Yet, even though the paper does try to adopt a multidimensional approach to animal metaphors, for methodological purposes five basic parameters will guide the analysis of this research, namely, habitat, size, appearance, behavior and relation of the animal to people (cf. Wierbizcka 1996a: 24–47, 1996b: 18–57; Martsa 2003: 27–49).

Before turning our attention to some of the most common animal metaphors encountered in the written press when presenting the relationship between women and food, a note should be made about how the most basic of all the instincts, that is, hunger is frequently conceptualized in our society.

Throughout history the desire for food has been the driving force leading humankind to survive and fight against and kill animals. And up to these days hunger is often conceptualized as an animal itself. The media are rife with images of women whose desires for food are portrayed as a wild animal:

(1) It is late at night and you feel the beast inside you. You head to the fridge and grab a snack… (Cosmopolitan, March 2013: 45)

(2) You skip breakfast and some hours later you hear the beast and go to the vending machine. (Women’s Health Magazine, April 2014: 72)

(3) Thanksgiving leftovers are too tempting….no wonder you can see the beast coming during the holiday season. (Self, October 2011: 37)

(4) After your workout you can sense the beast. What to eat and not to eat to maximize your exercise routine (Runners, June 2013: 15)

Interestingly, along with the depiction of hunger as a wild beast, the previous extracts are tinged with verbs pertaining to the semantic field of the senses (i. e. ‘feel’, ‘hear’, ‘see’ or ‘sense’), reinforcing the dichotomy between the instinctual and rational sides of people that vertebrate most animal metaphors. As a matter of fact, as Kövecses (2003: 311–317) reminds us, instincts tend to be understood as captive animals, trying to break free from the control of the rational human. This notion of captivity is certainly seen at work in the following fragments in which a woman’s desire for food is portrayed as a violent animal trapped in her body, using its claws and tearing the skin in order to escape.

(5) When you are on a diet, you often have that beast inside you asking for ice-cream, cookies and fast food. It tears your stomach with its claws and it is painful, but you must resist the urge (Cosmopolitan, March 2014: 82)

This painful scene evoked by resorting to the animal scenario is commonplace in the discourse of people suffering from eating disorders. Research has shown how patients describe their state of being hungry by using the metaphor of the menacing animal going berserk inside their bodies (cf. Twohig/Kalitzkus 2008: 103–117).

The idea of hunger as a mad animal is superbly condensed in the following example in which hunger is personified as a wild creature yelling, screaming and kicking in order to be released from the confinements of the human body.

(6) Runger: How runners can tame the beast and eat to perform. There’s a little beast that lives inside every runner. He gets really irritable after long runs. He’ll yell, he’ll scream, he’ll kick, he’ll throw a full on Toddlers and Tiaras style tantrum until you give him what he wants. He’s screaming, “FEEEEED ME!!!!” (Men’s Health, June 2015: 45)

Needless to say, if hunger is understood as a dangerous creature, it must be controlled or, using animal terminology, tamed. There are examples galore encouraging women to stick to their diets by suppressing their appetite with a variety of tricks. By making reference to the animal kingdom, women are, in theory, given the reins of their bodies; yet, when reading the advice provided by some publications, one soon realizes the dangers involved in following those guidelines for they promote starvation in order to obtain unattainable canons of beauty:

(7) The Cosmo Bikini Diet: Lose 15 Pounds & Get a Sexy Body. Sipping water is an appetite-taming move (Cosmopolitan, April 2015: 10)

(8) 8 Ways to Tame a Raging Appetite (Cosmopolitan, May 2014: 87)

(9) Use our 13 tricks to avoid these triggers and tame your appetite. (Women’s Health, August 2013: 14)

On other occasions, the instinct of hunger is so powerful and, therefore, difficult to control by a woman that she herself turns into another beast. Yet, hunger, it seems, is by far a more menacing and stronger creature awaiting for the vulnerable woman (i. e. its prey) to succumb to food.

(10) Don't fall prey to a snack attack! Healthy (and tasty) snack ideas (Cosmopolitan, May 2014: 35)

(11) Are you sabotaging your diet? Check out nine surprising habits that could be wreaking havoc on your waistline. You walk with your girlfriends at lunch and have sworn off candy bars in exchange for low fat snacks. So why is the scale not budging? Despite our best intentions, we all fall prey to habits that are plumping us up—even if we don’t realize they are. Here, sneaky traps that can sabotage weight loss and what you can do about them (Woman’s Day, March 2015: 26)

It does not come as a surprise when dealing with the mixture women and food that pig is the most common token found in the course of this research. The animal par excellence associated with compulsive eating, dirtiness and greed, the pig is commonly used as a term of abuse for females. In terms of its appearance, pigs stand out for their fatness and ugliness. No wonder, then, the metaphor targets women who are not slim, as shown in the extracts below:

(12) Britney has definitely become a pig after her break up! (Star, February 2009: 45),

(13) Some women just turn into pigs as soon as they get into a relationship (Star, April 2013: 32)

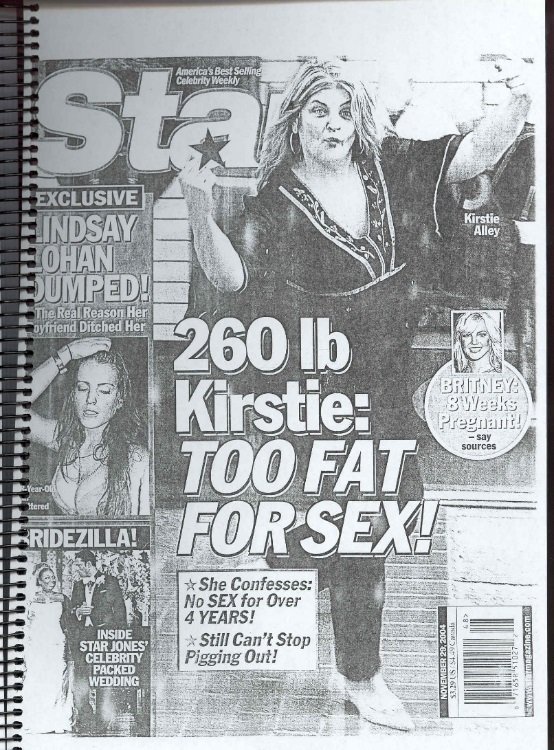

Yet, more often than not, the pig is associated with eating and, therefore, the verbal form pig out is frequently encountered in the press when presenting women who overindulge in food. Interestingly, to make the connection between the animal and food even stronger, photographs are often used. Extract number 14 belongs to the front cover of a magazine in which an actress is ridiculed for being fat. Her weight issues are somehow explained by stating her inability to control her appetite.

(14) Still Can’t Stop Pigging Out! (see image 2)

Image 2: Star, November 2009: front page

In other instances, however, instead of choosing the photograph of an overweight woman, the press resorts to images of attractive women, even top models, either indulging in or surrounded by food. This might seem as a threat to females, implying the dangers of losing their control with food for they may become a pig, that is, unattractive and fat.

The following examples are taken from popular fitness magazines. Theoretically promoting a healthy lifestyle, these publications reinforce the dangers of not controlling food intake by presenting fit women indulging in food. The first image shows a toned woman holding a big slice of red velvet cake with her hands (notice that not using a plate is linked to the connotations of bad manners that also stem from the metaphoric pig) whereas the second one recalls a common experience of opening the fridge at midnight in search for a snack.

(15) Why Do You Pig Out After You Work Out? It's a vicious cycle: You sweat your butt off at the gym, then stuff your face when you get home. (Shape, May 2015: 3) (see image 3).

(16) Food regret? Before you beat down on yourself for pigging out, we have six reasons you’re better off not stressing over it. ( Self, November 2013: 76) (see image 4).

Image 3: Shape, May 2015: 3

Image 4: Self, November 2013: 76

For a similar purpose, photographs of top models are used as a warning for females to always keep an eye on their diets. In the following extracts Victoria’s Secret models reveal their strict regimes, which include fasting for weeks, going on liquid diets and intense workouts. Despite the fact that what they do is obviously unhealthy and even dangerous, these women are looked up to because of their strong will to control their impulses regarding food. However, when they do succumb to food, they are portrayed as pigs, as shown in the articles below:

(17) Lily Aldridge Pigs Out After Victoria's Secret Fashion Show (US Magazine, May 2015: 18)

The press certainly takes advantage of the strong association between the pig and the possibility of gaining weight in countless articles dealing with dieting and working out. In fact, it appears that when women do not stick to a strict diet they are linguistically punished by reducing them to the animal realm. Losing control of their appetite, then, transforms females into an animal. The examples below are extracted from articles offering advice to women who have pigged out, that is, cheating on their diets, so that they can go back on track:

(18) Your Post-Pig-Out Plan (Shape, 2016: 3. www.shape.com/healthy-eating/diet-tips/your-post-pig-out-plan [16.02.2016])

(19) How to Pig Out on Thanksgiving (But Without the Guilt). The average T-day meal packs a whopping 3,000 to 4,000 calories. Add in second and third helpings and you can end up looking like someone stuffed a pumpkin into the back of your skinny jeans. This year, fend off the holiday flab (the average person packs on 9 to 11 pounds between now and New Year's) by making these smart (and not too painful) swaps (Cosmopolitan, November 2009: 24)

(20) Starve one day, then pig out the next! Is this the perfect diet? Gorging yourself on as many burgers, chips and cakes as you like one day then eating fewer calories than you find in a cheese sandwich the next might sound like a worrying eating disorder. But this regime of chomping away to your heart’s content one day, and virtually starving yourself the next is the latest diet craze. It’s known as ‘intermittent fasting’ or ‘alternate-day dieting’, and devotees insist the pounds just drop off. (Daily Mail, August 29th 2015. www.dailymail.co.uk/femail/article-2195408/Starve-day-pig-Is-perfect-diet.html [16.02.2016])

(21) Party’s over: Time for the post-pig out plan. A 3-day detox diet to purge holiday pounds even before the tree’s down. (Women’s Health, 2016. www.nbcnews.com/id/40573146/ns/health-womens_health/t/partys-over-time-post-pig-out-plan/#.VsO-WxZ0GcI [14.02.2016])

Aside from the associations with compulsive eating, the idea of dirt also resonates in the pig metaphor. First, as far as the habitat of the pig is concerned, a pigsty is a filthy place which tends to stink. Besides, pigs are well known for enjoying being in the mud, which at times accounts for their distinct odor, and are often fed with leftovers. Furthermore, the way in which pigs eat is characterized by noises and mess, which explains its associations with bad manners.

The pig is also considered an unclean animal in Judaism and Islam. The consumption of pork is regarded as a sin, which explains its connotations of dirtiness. In addition to this religious symbolism, pigs carry a load of abuse because, as anthropologist Leach (1964: 33) states, within farmyard animals pigs are raised for the sole purpose of being killed. After all, sheep provide wool, cows and goats give milk and chickens have eggs, but pigs will become food.

Food contests are the most obvious epitome of overeating and lack of manners. They are certainly the ideal breeding ground for the pig metaphor. These celebrations of food do bring out the most basic instinctual side of people and, therefore, contestants are quickly linked to different sorts of animals. However, whereas men are extolled for partaking in these sorts of competitions since they can boast about their strength, women, once more, are ridiculed and degraded to the category of pigs. The next article taken from a newspaper superbly encapsulates how the act of eating is channeled differently depending on whether the agent is male or female. So while men devouring food are seen as perfect human beings, women performing the very same action are labelled as pigs.

(22) Coney Island hot dog contest adds women's pigout NEW YORK (AP) — This year's Fourth of July race to stuff your face with hot dogs has a new women-only pigout. (USA Today, March 2011: 2)

Research has shown how in the encoding of animal metaphors women tend to be conceptualized mainly as domestic animals due to their biological role in reproduction as well as to their traditional position in the domestic environment (see López-Rodríguez 2007: 39–42). When it comes to the metaphoric pig such traits are definitely activated for the pig is a highly fertile animal. Some articles seem to exploit this biological connection by equating the natural cravings that pregnant women experience with the act of eating like a pig, as seen below:

(23)

Now that Megan Fox is pregnant, what will be her crave treat of choice? The “Transformers” actress and mainstay on those “Sexiest Woman Alive” lists

revealed her growing belly earlier this week while vacationing with husband Brian Austin Green. She gave up her vegan diet last year, dismayed that she

had lost too much weight. […] She'll likely be eating a bit more of everything now that she's expecting. If she needs inspiration for pigging out, she can get it from her fellow celebs.

(Entertainment, 2012 June 27th. http://abcnews.go.com/Entertainment/stars-food-cravings-megan-foxs/story?id=16654938 [16.02.2016])

(24) Pink's Pregnancy Pig-Out! She's Totally Eating For Two! (Hollywood Life, 2010 December 17th. http://hollywoodlife.com/2010/12/15/pink-pregnancy-craving-pig-out-eating-for-two-mexicans [16.02.2016])

By the same token, the increased hunger commonly felt by women when on their period is also compared to a pig. Once again, it appears that the biology of a woman makes her more of an animal than her male counterpart. In the following article the increase in appetite during menstruation leads to the comparison of women with several animals: pigs and manatees. Once again, the picture accompanying the text reveals a woman trying to grab a multi-layered sandwich which does not certainly fit in her mouth.

(25) We eat like pigs while on our periods […] we eat the portions of a small manatee. If there's more than one thing to eat in the fridge, we're capable of eating all of it just because we're that hungry. I've ordered pizza, wings, ate easy mac, and ice cream in the span of two hours (I was on my period too so add chocolate and chips) (Self, 2014: 37)

Despite the fact that the media extol the stereotypical image of the woman as a mother, many publications also warn of the dangers of not keeping up with their physical appearance once they are in a relationship and with children. Assuming the busy schedule of moms, these are encouraged to dress up nicely and eat healthily at all times. Yet, the language used to convey this message frequently pertains to the farmyard ambience, as observed in the fragment below in which eating fattening foods like ice-cream is equated with pigging out whereas eating small portions of food due to their hectic lifestyle with kids is seen as grazing:

(26) Prevent love chub. So, while you want to feel comfortable in your relationship, you don’t want to get so comfy that you pig out on ice-cream while wearing stretch parts every night […] Busy moms tend to graze instead of sitting down for proper meals . (Fitness, October 2014: 107–108)

The metaphorical connection between the pig with the act of a woman’s eating has caught on in the press to such an extent that it has generated a whole network of spin-offs. So women who are fat or have gained some weight turn into pigs. The act of eating becomes pig out and, consequently, contests which consist of women eating lots of food turn into pig-outs. By the same token, the sound made by women when eating their food is the onomatopoeia oink. Finally, men who are somehow connected with fat women take on the role of porkers:

(27) Britney has become a real pig! (Star, August 2011: 24)

(28) Cheryl pigs out on Sundays apparently! We're glad to know there is one diet secret we share with the Geordie stunner. We often hear of the strict dietary plans and excruciating personal training programs that celebs put themselves through to look as fab as they do. Take Beyonce’s dramatic two-week Maple Syrup Diet for her Dream Girls role, for instance. (Closer, May 2010: 12)

(29)Why Do You Pig Out After You Work Out? It's a vicious cycle: You sweat your butt off at the gym, then stuff your face when you get home. Follow our seven simple strategies to end the oink-fests. (Shape, June 2015: 11)

(30) The members of Girls Aloud are famous for a couple of cracking singles and breathing fresh air into the world of reality TV pop-not for being porkers. But now their manager, Louis Walsh, reckons, they’ve been pigging out and has ordered them to lose weight. (New, September 2003: 3)

Image 5: Metaphorical network of PIG

Another farmyard animal frequently encountered in the press when dealing with the relationship between women with food is the cow. Like the pig, cows only exist to be exploited and eaten. They render service to people, either by helping them in farm labor or by producing foods (milk and meat).

Because of its big size the cow is an animal charged with negative connotations, for it definitely evokes fatness. In fact, more often than not, the term is used as an insult for females whose physique does not adjust to today’s canons of beauty, that is, extremely slim women, as shown below:

(31) Apocalypse cow! The reality star was photographed leaving the gym on Thursday (Star Magazine, November 2013: 23)

(32) After her break up, the singer has turned into a cow (Star Magazine, October 2012: 9)

(33) From gorgeous to… cow! (Top of the Pop, May 2003: 42)

On other occasions the figurative cow is applied to pregnant women. Here, along with the notion of fatness, breastfeeding might play a pivotal role in the coinage of the metaphor. It goes without saying that the cow is the animal most commonly associated with milk since traditionally human beings have obtained this food from this animal. The strong link between the cow and motherhood along with the size of a pregnant woman and the animal may certainly account for the figurative use of cow in the excerpts below:

(34) Jessica Simpson has certainly gained some weight during her pregnancy and does look like a cow (US Magazine, June 2014: 34)

(35) Britney confesses to feeling like a cow with her second pregnancy (Star, October 2009: 15)

(36) Pregnant Snooki “Scared” to Breastfeed: “It's Like You're a Cow” (US Magazine, March 2012: 11).

(37) “You’re there trying to roll over like some sort of cow.” (The Mirror, September 2014: 29)

Leaving the farmyard ambience, another set of metaphors commonly found in the press when dealing with the relationship between women with food pertains to the wilderness. This time as opposed to creatures that co-exist with humans and depend on them for their sustenance as well as survival, women are presented as wild beings, for they are wolves and whales.

Obviously, when it comes to establishing a link between women with food and whales, size plays a major role. One of the biggest animals, whales are huge and heavy mammals. The immense weight of this creature explains its figurative application to big women, as seen in the next examples:

(38) Kirstie Alley has become a whale! (US Magazine, June 2011: 9)

(39) Kim Kardashian looks like a real whale (Now Magazine, July 2014: 5)

On several occasions along with its weight the habitat of this animal paves the way for its metaphoric usage. Indeed, whales are sea creatures that at times get stuck on shore and eventually may die. This tragic image of the stranded animal is recreated in several extracts in which voluptuous women are lying on the beach. Obviously, being in their swimming suits makes a woman’s body more noticeable and an easy target for the press. The next extract resorts to the whale metaphor in order to refer to women who are not slim while they are sunbathing:

(40) Celebrities that look like beached whales (US Magazine, August 2013: 4)

Just like with the animal metaphors above the media often illustrate the figurative use of whale with photographs of curvy women in bikinis:

(41) Lauren Goodger is DISGUSTED about THOSE bikini pictures – says she looks like 'beached whale'. The former TOWIE star flaunted her body as she bounded across the sand in Egypt – but now admits she had hit rock bottom with her weight (The Mirror, June 2014: 45) (see image 6).

Image 6: The Mirror, June 2014: 45

Another recurring pattern underlying the whale metaphor has to do with pregnancy. Like in the previous animal-based metaphors analyzed, the state of being pregnant, with its natural weight gain, places women in the category of animals, as shown below:

(42) Kim Kardashian Pregnant Whale (Star, June 2014: 28)

(43) Natalie Portman wants to enjoy pregnancy but she is looking like a whale (People, May 2011: 19)

As far as wolves are concerned, these predatory animals tend to live and hunt in packs. Their voracious and fierce nature when hunting finds its human parallel in the eating of females. Once again women are encouraged to control their appetite in order to adjust to the thin ideal. Failure to control such a primal instinct reduces women to the category of animals. The following example superbly encapsulates how women are praised for their ability to be on a diet and fitness regime, that is, to control their appetite. However, they are linguistically ostracized to the animal realm if they are enjoying their food. In a magazine article an actress and her male friend are photographed eating out in a restaurant. While the woman is depicted as wolfing down her food, no animal-related verb is used for the same action performed by the man.

(44) Tucking in! Newly slender Francesca Eastwood wolfs down her food while lunching with billionaire banana heir. She recently revealed her toned bikini body after overhauling her diet and fitness regime. But Francesca Eastwood appears to be following a plan that actually allows her to eat. The 19-year-old was seen happily tucking into her food while out for lunch with billionaire Dole Food heir Justin Murdock and another friend in West Hollywood on Sunday (Daily Mail, May 13th, 2013: 4) (see image 7).

Image 7: Daily Mail, May 13th 2013: 4

Taking into account the examples analyzed so far, it appears that the cocktail women and food is tinged with negative evaluations that are frequently channeled through animal metaphors. In the case of the metaphoric wolf down the predatory nature of the animal tends to be reinforced by highlighting that the food eaten is fast food, that is, high in calories and, therefore, basically forbidden for women, who need to be slim, as stated by society. The next examples present the act of eating hamburgers, French fries and other high-calorie dishes by women in the guise of wolf down:

(45) She Can’t Stop Eating! While at an LA eatery with kids Lillie, 10, and William, 12, on Nov. 13, Kirstie Alley wolfed down ketchup-and-grease-laden fries. (Star, November 2004: 48)

(46) Gwyneth Paltrow wolfs burger on a rollercoaster (The Toronto Sun, February 2012: 3)

(47) Margot Robbie Goes Makeup Free as She Wolfs Down a Burger on the Streets of London (US Magazine, December 2014: 45) (see image 8).

Image 8: US, December 2014: 45

(48) MINKA KELLY, the “sexiest woman alive,” slides a fork into a tangle of spaghetti carbonara. Zoë Saldana has a basket of fried calamari. Jennifer Lawrence, an Oscar nominee for her leading role in “Winter’s Bone,” wants it known that a skimpy morning repast is not going to satisfy her […] They’re so sure that people assume they have an eating disorder that they’re forced to wolf down caveman-like portions of ‘comfort food’ in order to appear normal. And worse, they feel they have to comment on how much they’re enjoying themselves. (New York Times, October 2011: 16)

(49) Kim was wolfing down fried chicken and waffles, buttermilk biscuits, mashed potatoes, mac n’ cheese, collard greens with bacon and fried green tomatoes with goat cheese. (US Magazine, June 2013: 53)

(50) Who really cares about the food at weddings anyway? It’s all about the booze. And wolfing down canapés. (US Magazine, April 2015: 42)

As is well-known, the beauty industry has found a powerful ally in the media to create an unattainable canon of beauty for females and make a huge profit at the expense of women’s health. Models whose weight borders on anorexia have become the norm and, as a result, diets have proliferated as never before. Even in those supposedly health magazines directed to women, these are given a series of tricks to suppress their hunger and burn more calories with exercise routines. Failure to comply with these norms results in the degradation of women to the animal kingdom. The next two examples are taken from fitness magazines. The first one resorts to the metaphoric wolf down to convey the negative view of women eating whereas in the second one not only is the act of eating chips seen as a predator devouring its prey but also women as a whole are seen as animals for they are labeled as breed.

(51) You Wolf Down Your Food to Get the Meal Over With. Eating with others means taking well-paced conversation breaks, and that gives your brain time to register fullness so you know when you’re done, says Heinberg. When you eat by yourself, you don’t have those talking and listening pauses, so you tend to eat faster and don’t feel as satiated. The fix: If you have trouble simply telling yourself to slow down, try putting down your fork between bites. It will automatically stop you from speed eating . (Women’s Health, May 2014: 48) (see image 9).

Image 9: Women’s Health, May 2014: 48

(52) How To Crank Up Your Metabolism. Don’t settle for a sluggish system. Boost your calorie-burning superpowers with these expert tips to smoke fat 24/7 . Have you ever watched a slim woman wolf down a giant bag of Kettle Chips and then wondered where she puts it all? (You may also have other thoughts about this breed of woman but let’s skip over that). Well, she doesn’t put it anywhere. More likely she has a Maserati-fast metabolism that incinerates fat before it has had chance to latch on to her thighs. (Women’s Health, June 2015: 90).

The last article analyzed makes use of the word breed to refer to different sorts of women. Apart from its obvious figurative meaning, since etymologically breed refers to the race or lineage of animals, in the context of animal metaphors used by the press when dealing with the relationship between women with food, the metaphor becomes relevant since regardless of whether they are fat or slim, eat or starve, exercise or laze around, women are always equated with animals.

In other words, controlling their appetite does not confer women the same status as men for they will always be inferior to their male counterpart. In fact, within the hierarchical organization of THE GREAT CHAIN OF BEING men rank above women because traditionally the former are believed to be ruled by reason whereas the latter by their heart, which seems to bring the female sex closer to the animal kingdom. In addition, biological factors such as menstruation, pregnancy and breastfeeding have been used throughout history as arguments to support the more emotional or instinctual side of women. Therefore, given that there is a strong tendency to categorize females in the guise of beasts, the choice of the animal may provide a good insight into the expectations and beliefs that society holds about women (cf. Nilsen 1994: 268–271).

Broadly speaking, women tend to be classified into three main groups, namely, pets (e. g.: kitten, bitch), livestock (e. g.: mare, hen) and wild animals (e. g.: vixen, crow) (cf. López-Rodríguez 2007: 15–21). Depending on the traits of women that need to be highlighted some animals are preferred over others. When it comes to establishing a strong connection between females with food, as this paper has tried to show, pets are usually ruled out in favor of livestock and wild animals. Certainly, in order to instill fear in females regarding weight gain, fatness and, ultimately, unattractiveness beasts of a considerable size seem to be the most appropriate choices.

Size, in fact, appears to be a key factor for crediting the animal term with negative connotations. Small creatures may arouse sentiments of protection and affection, for they are seen as more vulnerable, in tune with the patriarchal view of women. As a matter of fact, as Hines’ works (1999a: 9–16, 1999b: 145–160) on English metaphors about women bear witness, one of the most common conceptualizations of desired women takes the form of small animals. The so-called DESIRED WOMEN AS SMALL ANIMAL metaphor establishes a connection between animals that are either small and or/young and young attractive women. Consider, for example, the terms kitten, chicken or bunny. All of them, a priori, tinged with positive connotations for they refer to young and beautiful females. On the other hand, bigger beasts may be perceived as menacing and dangerous, which accounts for the common pejorative import attached to most animals of a bigger size, such as mare, nag, seal, walrus or coyote, all of which are offensive when applied to females.

Besides, the smaller the size and the lesser the strength of an animal give people a decided advantage in the successful application of control. In other words, smaller animals are more submissive, just like the ideal woman. In this regard there seems to be a trend to minimize the role of women in society which is somehow reinforced in language through the use of diminutives (e. g.: sweetie), partitives (e. g.: a piece of cake, arm) and also figurative usages of small animals (cf. Hines 1999b: 145–160). It could be argued, then, that the negative views conveyed through the animal metaphors analyzed in this piece of research do not merely reflect a distaste for big women but also for powerful ones.

Apart from size, edibility may be another element to take into consideration when examining the connection between females, food and animal metaphors. In most cultures as pets are not edible their figurative uses are not suitable vehicles to convey the idea of food. By contrast, most farmyard animals are solely raised to produce food (e. g.: hens-eggs, goats-milk) and may even become food themselves (e. g.: cow-beef, pig-pork). Therefore, as seen in the articles before, the press frequently resorts to the farm ambience and cow and pig are commonly applied to females to convey the dangers of eating too much.

As for wild beasts, although they may be hunted and eaten, they are, more often than not, predators, that is, voracious eaters. This seems to be the ground for the metaphoric coinage of wolf down, as used in the examples above to describe the action of eating when the agent is the woman.

Judging from some of the articles compiled, when women are pregnant or have their periods, they are more likely to be equated with different sorts of animals. Biological factors, it appears, bring women closer to the animal kingdom. Apart from the obvious weight element, when females are portrayed in the guise of farmyard animals (cow and pig), they are depicted as creatures that perform the strictly animal functions of producing and rearing offspring (cf. Shanklin 1985: 375–400; Brennan 2005: 1–12). Needless to say, this corresponds with the patriarchal mentality that relegates women to the confinements of the domestic sphere, where they can become a mother and cook for husband and children.

The use of animal metaphors in the press to convey messages about body image is often reinforced by the use of illustrations. As has been noted, articles are often accompanied by photographs of females who are somehow connected with food. Shots of overweight females eating or sunbathing co-exist with those of toned women succumbing to or resisting scrumptious food along with expecting females dealing with hormonal changes and cravings.

The way in which the press conveys a message is a complex array of words and images. In terms of Semiotics, the interpretation of the message is a twofold process in which the visual image often overlaps the message transmitted. The tyranny of the body is a recurrent topic in the press and photographs of skinny women pervade the pages of magazines, setting up the standard of beauty in our society. Those women who do not conform to this stereotype of beauty become an easy target of attack and mockery, an attack that, as has been shown, is frequently made through animal metaphors.

Metaphors are indeed powerful mechanisms in the transmission and perpetuation of folk beliefs. Since metaphor operates with two domains simultaneously the overlapping of such domains in the transfer from a source to a target will inevitably hide certain aspects of the source domain (cf. Lakoff/Johnson 1980: 36). In this regard Low (1988: 27) affirms that in the metaphorical mapping of one domain onto another there is “a price” to be paid: “the price is that the fact that a vehicle highlights one aspect of the topic also implies that it plays down, or hides, others” and he continues to say that this hiding mechanism inherent in the very functioning of metaphor is essential “where what is hidden is unpleasant […] or personally disadvantageous to the speaker”. Therefore, because the entailments may very well be only partially understood, these may be covert means of maintaining values which are damaging to a particular social group (cf. MacArthur 2005: 71–79).

As a corollary, any analysis about the relationship motivating metaphorical identifications of women with animals should be carried out cautiously because, more often than not, such correspondences may hide important considerations about the way people understand women and their role in society.

Metaphors offer a window on the construction of social identities since they function as labels or social etiquettes. When it comes to the forging of social identities dualisms seem to play a pivotal role and the use of metaphors may reinforce the dichotomy between “the self” and “the other.” In this regard animal metaphors draw a clear boundary between the human and the non-human and, therefore, they are often employed to castigate those behaviors which are not socially acceptable, for, to put it in Altman’s words:

(Altman 1990: 504)

The press often resorts to animal metaphors to deride women whose bodies do not adjust to the standards of thinness imposed by society or to threaten those of the dangers of indulging in food. Throughout these pages it has been made clear that animal-based metaphors are used to forge a strong negative connection between females with food. Such a connection, needless to say, may prove perilous for women’s physical and mental health. Indeed, medical studies have demonstrated how these publications may encourage eating disorders in the female population (cf. Gauntlett 2002; Gough-Yates 2003; Ghaznavi/Taylor 2015).

The problem with these metaphors is that they have become so pervasive that their original intent may no longer be discerned. In fact, these metaphors are posited as truth and accepted at face value and not only is their success well attested in their widespread usage and acceptance but also in the metaphorical networks created, as seen with pig.

The media help women to make sense of their collective experiences by providing models for women to follow. Flicking through the pages of several publications, one soon encounters a host of repeated topics providing women with instructions on how to eat and look, creating homogeneity in the female group and leaving little room for individuality (cf. Curri 1999: 47–60). These publications, to some extent, dictate who women are instead of portraying real women, the media construct socially accepted notions of what women should be like. In other words the articles analyzed do not mirror women themselves, but rather, borrowing Gitlin’s (2003: 29) metaphor they become fun-house mirrors distorting reality. Unattainable canons of beauty bordering on emaciation, diets, tricks to lose weight, exercise routines and mockery of those women who do not achieve these goals appear to be the staple of these publications.

In any event, the deleterious models created by the media are not limited to the presentation of unattainable standards of beauty by means of photographs and illustrations but transcend the solely visual to enter the domains of language (cf. Gauntlett 2002: 12–36; Gough-Yates 2003: 1–28). As a matter of fact, many of the negative images found in the course of this research are conveyed through animal-based metaphors. Through the trinity women-food-animal metaphor females are encouraged to diet, starve and exercise non-stop should they want to be accepted as members of society. For this purpose, animal metaphors figure so commonly in the discourse of the media not only because, as Lévi-Strauss (1968: 10) noted, “they are good to eat” but also because “they are good to think with”.

Baider, Fabienne/Gesuato, Sara (2003): “Masculinist Metaphors, Feminist research”. Metaphorik 5: 1–30.

Baker, Robert (1981): “‘Pricks’ and ‘Chicks’: A Plea for ‘persons’”. In: Robert Baker/Elliston, Frederick (eds.): Philosophy and Sex. New York, Prometheus Books: 45–64.

Barcelona, Antonio (2003): Metaphor and Metonymy at the Crossroads. A Cognitive Perspective. Berlin/New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Brandes, Stanley (1984): “Animal Metaphors and Social Control in Tzintzuntan”. Ethnology 23: 207–215.

Brennan, William (2005): “Female Objects of Semantic Dehumanization and Violence”. www.fnsa.org/v1n3/brennan1.html [09.04.2015].

Calvo, Clara (1998): “Ideology and Women's Clothes. Fashion Jargon in the Daily Press”. In: Hernández, José I. A./Guijarro, Arsenio/Downing Rothwell, Ángela (eds.): Patterns in Discourse and Text. Ensayos de análisis del discurso en lengua inglesa. Cuenca, Ediciones de la Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha: 63–79.

Carver, Terrel/Pikalo, Jernek (eds.) (2008): Political Language and Metaphor: Interpreting and Changing the World. London: Routledge.

Chamizo, Pedro/Sánchez, Francisco (2000): Lo que nunca se aprendió en clase. Eufemismos y disfemismos en el lenguaje erótico inglés. Granada: Comares.

Curri, Dawn (1999): Girl Talk: Adolescent Magazines and Their Readers. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Deignan, Alice (2003): “Metaphorical Expressions and Culture. An Indirect Link”. Metaphor and Symbol 18/1: 255–271.

Demarest, Jack/Garner, Jeanette (2002): “The Representation of Women’s Roles in Women’s Magazines Over the Past 30 Years”. The Journal of Psychology 126/4: 357–369.

Dirven, René/Pörings, Ralph (2002): Metaphor and Metonymy in Comparison and Contrast. Berlin/New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Durkheim, Emile/Mauss, Marcel (1963) Primitive Classification. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Esenova, Orazgozel (2013): “Image Metaphor for Hair with the Animal and Plant Source Domains”. Acta Linguistica 7/1: 46–55.