http://dx.doi.org/10.13092/lo.79.3344

In the two decades since British marketer Simon Anholt coined the term nation branding in 1996, dozens of countries have made significant expenditures of time and money to improve their national brands, often by hiring expensive consultants and commissioning new logos, brochures, and advertisements. Although originally conceived as a marketing practice, nation branding has become a form of public diplomacy, which aims to build, manage, and improve a country’s image in the eyes of both domestic and foreign target audiences (Bassey 2012: 1). Unlike many international cultural relations (ICR) policies, however, which are intended to develop “we-feeling (collective identity)” (Aoki-Okabe et al. 2006: 14) within a national population, nation branding efforts tend to be outward-oriented efforts that transmit a particular image of a given country beyond its own borders. Nation branding campaigns are often launched in connection with major international events, such as the FIFA World Cup or the Olympics, but they also form part of an ongoing brand management strategy in many countries. In the past two decades, both Denmark and Germany have begun actively managing their national brands, albeit with mixed results, in order to attract tourists, investment capital, and customers from around the world, as well as to compete with each other, as close neighbors with similar economic-educational profiles, for cultural appeal.

One oft-cited measure of national brand success is the Anholt-Gfk Roper Nation Brand Index (NBI, cf. GfK s. a.). Launched in 2005, the NBI ranks global perceptions of countries with regard to culture, governance, people, exports, investment, and immigration, based on annual interviews with 20,000 adults in 20 countries. The fact that Germany has ranked in the top 5 countries on the index since its inception would seem to suggest that such efforts are a prudent and proven way to boost a nation’s brand. Indeed, in 2014, Germany supplanted the U.S. in the first place spot for the first time since 2008, due primarily to its large score gain for “sports excellence” in connection with winning the World Cup that same year (cf. GfK 2014).

Yet the NBI rankings also demonstrate how stable national brands tend to be, with the same 10 countries occupying the top ten positions year after year. Aside from Germany’s rise to 1st place and Russia’s fall to 25th, most countries’ rankings did not change appreciably in 2014, regardless of how much the country had invested in branding efforts. As Uffe Østergaard and Mads Mordhorst (2010: 6) point out, the 619 million Danish crowns that the Danish government spent on a massive nation-branding campaign did not elevate Denmark on the NBI from the 14th place standing it occupied in 2007. Instead, after investing 3 years and more than 300 million kroner in a re-branding endeavor, which included a now-defunct smartphone app for international journalists called “Denmark – Stay Tuned”, Denmark fell to 16th place on the NBI in 2010. However, on the FutureBrand Country Index, which looks at a different set of factors, including whether a country has a reputation for high quality manufactured goods and public infrastructure, as well as the interviewee’s desire to visit or study in the country in question, Denmark ranked 12th in 2013 and moved up to 9 th place in 2014.

Denmark’s failure to improve its standing on the NBI in 2010 despite its branding campaign, combined with the generally static national rankings on the NBI, suggests that national brands cannot simply be shaped by clever marketing campaigns, but rest on deeply rooted perceptions of a country’s character and identity, which often have much in common with popular stereotypes about a given country. These deceptively simple terms—character, identity, and stereotypes—mask a long and turbulent discursive history, during which cultures, peoples, races, and nations have been classified according to many different and often contradictory criteria. William L. Chew III notes that from the early nineteenth century until after World War II, the concept of national identity was largely essentialist, based on the premise that “an objective essence defining ‘national character(s)’ was scientifically identifiable in an empirical fashion” (Chew 2001: 6), but over the course of late twentieth century, the study of national stereotypes has come to concern itself more with perception and attitude. According to this school of thought, national identities are subjective constructs rather than mimetic representations of empirical reality. Once they were understood to be subjective discursive objects, constructions of national identity were ripe for commercialization as national brands in the twenty-first century.

Like retail brands such as Nokia, Volvo, and Walmart, national brands take decades to build and depend on the recognizability of the brand image being disseminated. This relatively long time horizon explains why national stereotypes play such an important role in branding and public diplomacy efforts—and why attempts to change a country’s image overnight in a blitz marketing campaign are doomed to fail. Social scientists define national stereotypes as “belief systems which associate attitudes, behaviors, and personality characteristics with members of a social category” (Cinnirella 1997: 37). As such, they can function as shortcuts to establishing a basic familiarity with a particular country/ethnicity, upon which branding campaigns can build. While stereotypes are broad generalizations that only apply to a relatively small percentage of a given country’s population or economy, they are often based on demonstrated characteristics that are perceptible to outside observers or casual visitors, such as the preponderance of luxury cars in Germany or Danes’ predilection for tea candles and brightly colored interiors. Utilizing positive stereotypes in branding efforts allows a country to trigger latent associations in viewers’ minds that can facilitate and accelerate the kind of image enhancement that the NBI measures.

This paper explores what role positive national stereotypes have played in recent efforts, by interest groups in both the public and private sectors, at developing Danish and German national brands. The main object of analysis is a series of ad campaigns, ranging from Germany’s government-sponsored “Land der Ideen” campaign during the FIFA World Cup in 2006 to several provocative recent Danish tourism promotions, which I will consider in terms of both their explicit and implicit references to particular attitudes and behaviors that have been culturally coded as stereotypical for either Germany or Denmark, as well as with regard to the international responses they may have provoked. This analysis will demonstrate how successful Danish and German nation branding endeavors reinforce and promote selective positive (though not always uncontroversial) cultural stereotypes in order to build positive global perceptions of and interest in their respective countries. While it is difficult to track the effect of such campaigns on individual citizens’ opinions, the utilization of familiar positive national stereotypes in nation-branding campaigns has likely made it easier for Danes and Germans to find common ground by establishing a basic level of brand familiarity that can serve as the foundation for future communicative cross-cultural endeavors.

In 2007, the Danish government commissioned an expensive nation-branding campaign with the goal of moving Denmark into the top ten list of the NBI by updating its national brand. At the launch of the campaign, Minister of the Interior Bendt Bendtsen declared, “In too many places, Denmark is known for bacon, butter, and Hans Christian Andersen. That is not enough. Denmark has much more to offer” (Mordhorst/Østergaard 2010: 8). After the branding campaign proved ineffective at boosting Denmark’s ranking on the NBI, however, as mentioned above, the Danish government decided instead to capitalize on the same well-known stereotypes of Danishness that Bendtsen had dismissed as inadequate. The statue of the Little Mermaid from Copenhagen harbor featured as the centerpiece of the Danish pavilion, alongside open-faced Danish sandwiches and bacon, at the World Expo in Shanghai in 2010. The flood of 5.6 million primarily Chinese visitors to the Danish pavilion, approximately 30,000 per day, was more than double the expected attendance and testified to the popularity of the Little Mermaid as a positive and persistent symbol for Denmark (cf. Ingvartsen 2012: 6). Mordhorst and Østergaard draw the conclusion from this about-face and its outcome that “nation states may well be ‘imagined communities’, but once they have been established, their strength lies in the stability of their images” (Mordhorst/Østergaard 2010: 8).

The residual effect on this strategic marketing of Danish stereotypes persisted long after the World Expo in Chinese public consciousness. When filmmaker Asbjørn Thorlacius made a video survey in the summer of 2013, asking Chinese people what they thought of when they heard the word “Denmark”, the most common answers were “Hans Christian Andersen”, “Vikings”, “green energy”, “Danish butter cookies”, “Danish design”, “welfare state”, and “soccer” (cf. Thorlacius 2013a). One respondent explicitly referenced the Danish pavilion at the 2010 World Expo in Shanghai. Another said of the Danes that “all of them are about 2 meters tall and ride huge bicycles” (Thorlacius 2013a). By contrast, a second video survey Thorlacius conducted in September 2013, for the Wonderful Copenhagen Chinavia project, about Chinese perceptions of the much vaguer term Beiou (which means either ‘Northern Europe’ or ‘Scandinavia’), most respondents simply stated that “it’s very cold” (Thorlacius 2013b), but made none of the concrete associations with specific Danish cultural markers that dominated the earlier survey. These differing results reveal that the branding of Denmark through the exploitation of familiar stereotypes at the World Expo was effective, but did not carry over into a broader regional brand for Scandinavia.

The Danish government’s decision to revert to evoking national stereotypes in the wake of an ineffective nation branding campaign illustrates the difficulty of simply rebranding a country with attributes that are not already associated with it, even if those attributes are authentic. As the buzz around nation branding as a field of marketing and the subject of scholarly inquiry has grown internationally, Simon Anholt has found it necessary to clarify – repeatedly – the difference between national brands and nation-branding. In a widely reprinted article, he declares,

(Anholt 2009)

Anholt’s point about the fundamental differences between the branding of places and things is important, since products and services are deliberately designed and can therefore be redesigned as necessary, whereas places emerge more organically. Many places are, of course, shaped by human design, as Baron Haussmann’s massive renovation of Parisian streets in the mid-nineteenth century illustrates. However, while cosmetic and structural changes can affect both the individual experience and public perception of a place, even one as symbolically and strategically important for a country as Paris is for France, they cannot replace or completely obscure the underlying, accumulated narratives about a place generated by eons of history. In addition, since nations are much more than the sum of the places than they contain, the difficulties involved in branding such an amorphous concept are far greater than the challenge of branding specific products.

In this 2009 article, and later in his book Places, Anholt rejects the idea that nation-branding can “fix” a country’s weak or negative image, citing the persistence of “comforting stereotypes that enable us to put countries and cities in convenient pigeon-holes” (Anholt 2010: 6). Although he admits that well-worn national stereotypes, including, for example, a perception of the British as stiff, the French as proud, Italians as sensuous, or Americans as brash, are too deeply rooted to be easily unseated, Anholt warns against reliance on them. He asserts that

(Anholt 2010: 3)

In his necessary corrective to the widespread misunderstanding of how nation branding works, however, Anholt goes to the opposite extreme. He lumps national stereotypes together as negative and makes no provision for the ways in which positive national stereotypes can do precisely what he now advocates, namely showcase a country’s people, landscapes, history, heritage, products, and resources.

It is important to point out that despite the commercial overtones of the phrase “nation branding” and the perception that it is a cutting edge marketing innovation, nation branding is nothing new. Effective nation branding is essentially good, old-fashioned public diplomacy that aims to promote a nation’s most positive attributes or attempts to frame particular national values as representative of the nation as a whole. Public diplomacy has long been the domain of non-governmental actors, including corporations, civic organizations, and even private individuals, notably artists, authors, and other celebrities. Unsurprisingly, perhaps, many of the most effective instances of recent nation branding efforts in Denmark and Germany have not been government-sponsored studies, but rather examples of public diplomacy, by which individuals, companies, and public interest groups have attempted to shape their country’s image for both domestic and international consumption.

As the failure of many overly-ambitious nation-branding campaigns in recent years makes evident, effective public diplomacy and nation branding efforts must build on what audiences and markets already know and believe about a place in order to be credible, but that does not mean that the national brand cannot be subtly redefined at the same time by the foregrounding of positive national stereotypes in place of negative ones. The rest of this paper will examine how recent nation branding campaigns in Germany and Denmark attempt precisely this feat of subtle rebranding through emphasis on particular positive national stereotypes, an endeavor which has implications for both their individual international reputations as well as, given their inescapable proximity and long shared history of competition, conflict, and cooperation, their perceptions of and interactions with each other.

In contrast to Denmark’s consistent ranking as one of the happiest countries in the world on regular international surveys, Germans are often perceived as stiff and inhospitable. A private-sector ad campaign to improve Germany’s public image during the 2006 FIFA World Cup confronts this stereotype head-on, countering it with an image of Germany as jovial and welcoming, though still competitive in a friendly way. The success of this effort is evident from journalist David Crossland’s assertion in Spiegel Online: “The 2006 World Cup host appears to have pulled off a coup no one had thought possible before the tournament began: a fundamental rebranding of Germany, a shift in the world’s view of the nation from dour and humorless to fun-loving and friendly” (Crossland 2006). Yet what Crossland calls re-branding was, in fact, more a matter of refocusing international attention on positive stereotypes of German culture rather than negative ones, in order to foreground the fun-loving and friendly aspects of Germany in place of its perceived dour and humorless attributes (cf. Crossland 2006).

When the 2006 FIFA World Cup ads play on well-known stereotypes of German culture, they use them deliberately to underscore positive associations with those stereotypes and shape visitors’ expectations for their experiences in Germany. One Bavarian-themed Pepsi ad, for example, uses the world-famous Oktoberfest as the setting for showcasing German hospitality, thereby displacing negative stereotypes of angry skinheads or officious German bureaucrats that might otherwise informs viewers’ perceptions of the host country. The ad features pretty blond women in Bavarian dirndls and jovial revelers welcoming their famous international footballer guests – including Ronaldinho, David Beckham, Thierry Henry, and Roberto Carlos – with a friendly sense of rivalry and free-flowing Pepsi (served in classic beer mugs, of course, cf. Pepsi 2010). The soundtrack of the ad begins with blaring horn music, then transitions to a cover of the 80s hit pop song by TRIO, “Da da da”. After a period of initial tension when the famous footballers enter the beer tent and face their rivals, a stout, bewhiskered gentleman invites the international players to participate in a spontaneous football match that replaces the tension with friendly rivalry. Despite the stars’ virtuosity, the troupe of Lederhosen-clad Germans manage, with the help of a stern dirndl-clad matron, to score a goal while performing a traditional foot-slapping dance, rather to the chagrin of the star footballers, who must console themselves with Pepsi and the flirtatious attentions of the blond waitresses. The sheer ludicrousness of the match’s outcome, within such a clichéd setting, suggests that Germans are able to laugh at themselves and with their visitors.

Figure 1: “Oktoberfest World Cup” (Pepsi 2010)

Through its tongue-in-cheek use of such well-known stereotypes of Bavarian beer culture, Lederhosen, and buxom blond women, the ad conveys an atmosphere of relaxation and celebration that resonated with foreign visitors and improved their perception of Germany and its World Cup team. Crossland reports that only a few days into the 2006 World Cup, then-British Prime Minister Tony Blair published an opinion piece in Bild am Sonntag about why British fans were supporting the German team. He declared, “The old clichés have been replaced by a new, positive and more fair image of Germany” (Crossland 2006). In Crossland’s view, this improved image of Germany that resulted from the World Cup campaign allowed “feelings of patriotism stifled for decades by the Holocaust” to resurface, “as Germans started attaching not just one but two and sometimes four national flags to their cars, painted neat little flags onto their faces and cleavages and donned wigs and bras in the national colors of black, red and gold” (Crossland 2006). The benefits of the effective use of positive national stereotypes allowed not only foreigners but also Germans themselves to reevaluate their view of Germany’s national brand and, by extension, national character. As a result, being German became something to be proud of, a sentiment that manifested itself in otherwise unusual displays of the German flag throughout the country during the event.

Public diplomacy is not limited to the private sphere, however, nor does the use of a particular national stereotype necessarily exclude the potency of other, complementary ones. At the same time as the boisterous FIFA ads highlighted German “partyotism”, as Crossland (2006) calls it, a concurrent campaign coordinated by the German government-administered “Land der Ideen” project celebrated German efficiency and innovation through a series of larger-than-life sculptures symbolizing German accomplishments that were placed throughout the center of Berlin. The sculptures featured on the “Walk of Ideas” included, from top left (below): the Revolutionized Soccer Cleat, the Milestone of Medicine, the Automobile, Musical Masterpieces, the Theory of Relativity, the Modern Printing Press (cf. DLI s. a.).

Figure 2: “Land of Ideas” (DLI s. a.)

Each of these sculptures highlights a well-known German invention or contribution to civilization, thereby underscoring Germany’s well-deserved reputation for technological prowess. Aimed at international visitors attending the World Cup, the sculptures function as an effective branding tool precisely because the iconography, all of which is evocative of positive developments in human society, is easily recognizable as German. In this case, no attempt is made to evoke and undermine a negative stereotype, as the Pepsi ad did, but simply to encourage viewers to reflect on Germany’s many positive contributions to modern society.

In most cases, the sculptures can be readily associated with well-known German-speaking individuals, such as Einstein, Gutenberg, Daimler, Bach, and Mozart, and thus with German culture, although neither Felix Hoffmann, the inventor of aspirin, nor Adolph Dassler, who invented the spiked track shoe, is a household name today. Many non-German visitors may not even have been not aware that Bayer and Adidas, which popularized Hoffmann and Dassler’s respective inventions, are German brands, but the scale and apparent permanence of the “Land der Ideen” sculptures, as well as the symbolic importance of their placement in Germany’s capital city, would have at least established the association in the viewer’s mind between the products being depicted and German ingenuity.

In Denmark, a private-sector equivalent to the German “Land der Ideen” campaign can be found in a series of ads made by a Danish transportation company, Midttrafik, in 2012, which promote public transportation. Unlike Germany, Denmark is not renowned for its luxury automobile manufacturing sector or high-speed highways, but it does have a well-developed public transportation network. Instead of trumpeting the efficiency and reliability of this network, however, as one might do in an automobile commercial, the Midttrafik ads apply self-deprecating Danish humor to an otherwise mundane service, thereby selling a Danish worldview as much as promoting the product itself.

The first ad in the series, titled Bussen (‘The Bus’, cf. Midttrafik 2012), uses a dramatic off-screen narrator and slow-motion pantomime to tout the benefits of riding the bus, with its plush seats, big windows, designer bells, free grips, and cool drivers. Crowds of people fight to board the bus, caress the seats, and gaze in fascination at the “impressive views” (Midttrafik 2012) of their neighbors taking out their trash.

Figure 3: “The Bus” (Midttraffik 2012)

The ad’s exaggerated acting style, sly innuendos, and obvious irony are clearly intended to amuse viewers and keep their attention while the narrator extols the virtues of a mode of public transportation that is often considered a poor-man’s alternative to driving.

A follow-up ad, Buskunden (‘The Passenger’, Midttrafik 2015), challenges this negative perception of public transportation by making good-natured fun of the stereotype of bus riders as unfashionable geeks in order to send the opposite message, namely that riding the bus is cool, sexy, and very Danish, as well as attractive to foreigners, such as a swimsuit- and tiara-clad Miss Uruguay, who watches the passenger, whose appearance resembles that of the title character of the 2004 American cult film Napoleon Dynamite, with wide eyes and parted lips in obvious, sensual admiration (cf. Midttrafik 2015).

Figure 4: “The Passenger” (Midttrafik 2015)

Although the ads enjoyed considerable global popularity and a long digital afterlife on YouTube and Facebook, they were clearly aimed at a domestic audience of potential passengers. Besides attracting new customers, their aim seems to have been to reinforce and celebrate the ubiquity of public transportation as a desirable attribute of Danish culture, thus giving a very mundane aspect of Danish life significant social prestige. When viewed as part of a larger Danish nation-branding agenda, the ads take on additional significance for their reinforcement of the positive stereotype of Danes as informal, irreverent, environmentally conscious, and fundamentally pragmatic, while implicitly contrasting Denmark’s image as eco-friendly with the auto-centric culture associated with Germany.

Using stereotypes in nation branding is not without risks. This strategy can produce negative backlash when the stereotypes offend viewers or conflict with a country’s inhabitants’ own self-perception, even if they accomplish the goal of attracting attention to the country in question. Although both Denmark and Germany have strong traditions of Christian belief and practice that frown on sexual promiscuity, Denmark is often associated, alongside its Scandinavian neighbors Sweden and Norway, with sexual permissiveness. An ad called “Danish mother seeking” that aired on YouTube in 2009, in the guise of a private video blog, or vlog plays with those stereotypes in a provocative manner that attracted significant international attention, both affirming and condemnatory (cf. Visitdanmark 2009).

The apparently amateur three-minute video depicts an attractive young Danish woman named Karen, who claims to be trying to locate the father of her young child by recounting for the online world how she met a man, whose name she can’t remember, in a bar in Copenhagen and took him home with her one night. The one thing Karen does remember is that she and her baby’s father chatted about hygge, the allegedly untranslatable Danish concept of coziness that Danes are known for. She claims that the point of the video is simply to alert this unknown man to the existence of his child, but not to ask him for any kind of financial or even emotional support.

Figure 5: “Danish Mother Seeking” (Visitdanmark 2009)

In fact, however, the video was targeted not at a specific individual, but at a generic foreign audience. It was not an amateur video at all, but an example of stealth marketing by the Danish national tourism agency, as a brief credit for a (now-defunct) Danish tourism site (www.visitdenmarknow.com [13.02.2016]), at the end of the video reveals. The fact that Karen, played by actress Ditte Arnth Jørgensen, speaks English in the video, combined with the story that she tells about how she met the father of her child, seems to convey the message that men should come to Denmark in hopes of meeting an attractive, sexually available woman like Karen.

The (belated) realization that the video was an ad offended many viewers, both those who had initially applauded Karen’s courage in making such a public plea and others who felt that the branding of Denmark as sexually permissive was inappropriate. Public outcry prompted the Danish government to pull the ad after four days, but it had already caught the media’s attention in many countries. The ad was condemned on the conservative American talk showThe O’Reilly Factor in the fall of 2009 for promoting promiscuity and humorously dissected on the liberal/progressive American online talk show The Young Turks, hosted by Cenk Uygur, who concluded, “Here’s the one sentence that they want to go through your head: ‘Oh yeah, Denmark has hot chicks!’” (Uygur/Kasparian 2009). If the aim of the ad was to attract international attention to Denmark by exploiting familiar and therefore believable national stereotypes, it was certainly a success.

As an example of nation branding, however, this ad raises a number of questions about the extent to which national stereotypes can be controlled, manipulated, and redefined. In an article on the online news site Huffington Post on September 15, 2009, Danish sociologist Karen Sjørup identifies the ad’s message as “you can lure fast, blond Danish women home without a condom” (Huffington Post 2009), but in the same article Dorte Kiilerich, the manager of the VisitDenmark.com website, explains that the tourism agency’s intent had been to tell “a nice and sweet story about a grown-up woman who lives in a free society and accepts the consequences of her actions” (Huffington Post 2009). As laudable as Kiilerich’s stated aim may have been, the ad’s attempt to define Denmark by its support of individual responsibility could not compete with the popular stereotype of attractive, blond, sexually liberated Scandinavian women that dates back at least as far as the notorious Swedish film I am Curious (Yellow) (Vilgot Sjöman 1967), which features both nudity and staged intercourse in its depiction of a young Swedish woman’s sexual adventures.

Regardless of the morality of the story that Karen tells, what is incontestable is the viral international spread of the video, which attracted more than a million views on YouTube from more than 150 countries and spawned dozens of copycat videos, responses, and parodies (cf. Stage/Andersen 2012: 394). These statistics indicate that the ad was indeed successful in raising global awareness of Denmark and associating it with a recognizable national brand, albeit not necessarily one that all Danes were comfortable with. In terms of the relationship between Germany and Denmark, the ad also set Denmark apart from Germany’s more straight-laced image (though it may well have appealed to individual Germans).

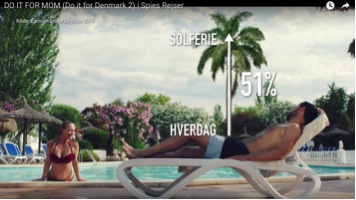

While the “Danish Mother Seeking” ad was clearly directed at foreign audiences as a ploy for generating tourism to Denmark, a 2013 ad campaign called “Do it for Denmark” features an equally attention-getting approach that capitalizes on Denmark’s vaunted sexual openness, but (ostensibly) aimed at Danish consumers. The ad, sponsored by the Spies Travel agency, opens with a close-up of a woman’s body and the question, posed by an off-screen narrator and printed across the screen, “Can sex save Denmark’s future” (Spies Rejser 2014)?

Figure 6: “Do it for Denmark” (Spies Rejser 2014))

In documentary fashion, the narrator cites Denmark’s declining birthrate and the inability of successive Danish governments to solve the population crisis, before explaining that Danes tend to have significantly more sex while on holiday and therefore a greater likelihood of conceiving a child while abroad. The ad frames the decision to go on holiday and have sex as a patriotic decision and encourages viewers to do their part to boost Denmark’s birthrate. As an incentive, the company offered a reward of a three-year supply of infant necessities to a lucky couple that conceives while on a holiday booked through Spies Travel. The company’s website even featured an ovulation calendar to help couples plan their holiday to coincide with their peak fertility. The ad’s sly humor and inclusive outreach is every bit as Danish as the stereotype of Danes’ uninhibited views of sex. The ad consoles those viewers who may be too old, gay, or otherwise unlikely to conceive to compete that they too can do their part simply by participating. “Do it for Denmark!”

The “Do it for Denmark” ad, which is narrated in Danish but subtitled in English, made a splash on social media and attracted international attention, though neither as widespread nor as scandalized a response as “Danish Mother Seeking” provoked. Both The Young Turks and TheLipTV devoted an entire segment of their shows in April 2014 to discussing the ad and dusting off stereotypes about Denmark being a highly-regulated welfare state. While The Young Turks focused on the invasively intimate physiological information that the competition required (as well as referencing Hamlet and breakfast Danishes), Ondi Timoner, the host of TheLipTV, debated whether the competition format trivialized the decision to have a baby or whether it was just a really smart marketing campaign for Denmark itself. As evidence for the latter, Timoner notes Denmark’s impressive GDP and consistently high rankings on global happiness surveys. Co-host Gabriel Mizrahi speculates about Denmark’s motivation for wanting more children and concludes that the ad will have a negative effect: “I think this campaign is all sorts of bad and it’s probably going to spell the end of Denmark as the great, happy, rich country that it is.” While the jury is still out on the accuracy of his prediction, the ad drew global attention to Denmark and Danish sexuality once more, prompting one commenter on TheLipTV’s site to plead, “Send me to Denmark! I can help!!!”

The release of a follow-up ad, “Do It for Mom”, in September 2015 confirms the original ad’s effectiveness as a marketing tool for Spiess Travel, while the repeated use of the well-worn trope of Danish sensuality suggests that the overall reception of the initial ad must have been positive. The provocative opening sequence of “Do it for Mom” (Spies Rejser 2015) features a close-up of a woman’s head, sweaty neck, and nude shoulders, apparently in the act of copulation. The new ad reiterates its predecessor’s concern with Denmark’s falling birthrate, then turns to the issue of the pain suffered by women who long in vain for grandchildren. Rather than depicting the decision to have a baby as a primarily patriotic one, “Do it for Mom” couches it in terms of filial duty and ethical responsibility. One scene in which the prospective grandmother attempts to assist in the process of conception by removing his son’s partner’s bra as the couple kisses nods toward Danish irony, while subsequent suggestive graphics and sports montages reinforce the stereotype of northern Europeans gravitating toward sunny southern vacation destinations in search of erotic adventure. In this last area, at least, Germans and Danes can find common ground.

Figure 7: “Do It for Mom” (Spies Rejser 2015)

As Simon Anholt’s retreat from the term nation-branding confirms, no amount of branding can change a country’s essential character, nor can countries be branded as easily and arbitrarily as products and services. This realization has prompted Anholt to shift his focus from branding campaigns to policy reforms that can help countries become more like the image they hope to convey. In this spirit, he founded the Good Country Index, which measures how virtuous and responsible countries are, and the Good Country Party, an online forum for people around the world to collaborate on coming up with “more creative and imaginative solutions to global and local challenges” (GCP s. a.). He has also established the Anholt Institute in Copenhagen, with seed money from the Danish government, which aims to help countries “focus more on collaboration and less on competition, so they can play a greater role in tackling the global issues facing humanity” (AI s. a.). Yet while increasing global cooperation is an admirable and necessary goal, countries will still compete for global market share, for which reason the selective affirmation of positive national stereotypes will continue to play a central role in nation-branding efforts for many years to come.

Since, as Anholt (2010: 3) himself admits, national stereotypes are deeply ingrained in international public opinion, it makes sense for countries to use them strategically in their attempts to shape their national brands, as the above examples illustrate, rather than simply rejecting them. National stereotypes are often based on authentic characteristics, even if they are only applicable to one small part or population segment of a given country (not all Danes are like Karen, for example, just as not all Germans are like Bach). This congruence between the stereotype and observable reality creates an opportunity for affecting international perceptions of a country, as well as for facilitating cross-cultural communication. By selectively prioritizing and foregrounding specific positive national stereotypes in nation-branding efforts, public and private groups can engage in effective public diplomacy, leap-frogging past the initial effort of familiarizing audiences with the national product they’re selling, while still retaining some control over the national branding message they want to convey.

The similarities between the stereotype-based approaches taken in the various German and Danish ad campaigns analyzed above reveal the continuing relevance and potency of such widespread beliefs about the attitudes, behaviors, and characteristics of a given nation. At the same time, the differences between the particular national stereotypes they affirm or challenge underscore the constructed nature of nation brands as discursive objects that can and are being constantly, incrementally redefined.

AI = The Anholt Institute (s. a.). www.regionh.dk/anholtinstitute/about-us/Pages/default.aspx [13.07.2015].

Anholt, Simon (2009): “Why Nation Branding Does Not Exist”. Kommunikationsmaaling.dk 2007-2011. http://kommunikationsmaaling.dk/artikel/why-nation-branding-does-not-exist/ [13.07.2015].

Anholt, Simon (2010): Places. Identity, Image and Reputation. New York: Macmillan.

Aoki-Okabe, Maki/Kawamura, Yoko/Makita, Toichi (2006): The Study of International Cultural Relations of Postwar Japan. Chiba: Institute of Developing Economies, JETRO. www.ide.go.jp/English/Publish/Download/Dp/pdf/049.pdf [30.01.2016].

Bassey, Cocomma (2012): Understanding Nation Branding: A “New Nationalism” in Germany. Unpublished M.A. thesis, Brandeis University.

Chew, William L. (2001): “Literature, History, and the Social Sciences? An Historical-Imagological Approach to Franco-American Sterotypes”. In: Chew, William L. (ed.): National Stereotypes in Perspective: Americans in France, Frenchmen in America. Amsterdam/New York, Rodopi. 1–53.

Cinnirella, Marco (1997): “Ethnic and National Stereotypes: A Social Identity Perspective”. In: Barfoot, C.C. (ed.): Beyond Pug’s Tour: National and Ethnic Stereotyping in Theory and Literary Practice. Amsterdam, Rodopi: 37–52.

Crossland, David (2006): “From Humorless to Carefree in 30 Days”. Spiegel Online 10.07.2006. www.spiegel.de/international/germany-s-world-cup-reinvention-from-humorless-to-carefree-in-30-days-a-426063.html [13.07.2015].

DLI = Deutschland – Land der Ideen (s. a.): “Walk of Ideas”. www.land-der-ideen.de/projektarchiv/walk-ideas/walk-ideas [13.02.2016].

GCP = The Good Country Project (s. a.). www.goodcountry.org/index_intro [13.07.2015].

GfK = Anholt-GfK Nation Brands Index (2014): “Germany knocks USA off Best Nation top spot after 5 years”. www.gfk.com/en-in/insights/press-release/germany-knocks-usa-off-best-nation-top-spot-after-5-years-1 [13.07.2015].

GfK = Anholt-GfK Nation Brands Index (s. a.). www.gfk.com/countries/master/home] [22.05.2016].

Huffington Post (2009): “‘Danish Mother Seeking’ Denmark Tourist Teaser is Pulled From YouTube for Promiscuity”. www.huffingtonpost.com/2009/09/15/danish-mother-seeking-den_n_287483.html [13.07.2015].

Ingvartsen, Nina Marie (2012): “欢 迎光临丹麦馆: Welcome to the Danish pavilion - A cultural translation on the basis of scenarios outplayed at the EXPO 2010 in Shanghai”. University of Copenhagen: Institute for Cross-Cultural and Regional Studies (Cultural Translation, Summer Exam 2012). www.academia.edu/6081747/欢迎光临丹麦馆_Welcome_to_the_Danish_pavilion__A_cultural_translation_on_the_basis_of_scenarios_outplayed_at_the_EXPO_2010_in_Shanghai [13.07.2015].

Mordhorst, Mads/Østergard, Uffe (2010): “Nation-branding – en humanistisk disciplin? ” In: Klüver, Per Vingaard (ed.): Nation Branding. Aarhus, Den Jyske Historiker: 4–12.

Stage, Carsten/Andersen, Sophie Esmann (2012): “Ambiguous Imitations: DIY Hijacking the ‘Danish Mother Seeking’ Stealth Marketing Campaign on YouTube”. Culture Unbound 4: 393–414. www.cultureunbound.ep.liu.se [13.07.2015].

Midttrafik (2012): „Bussen“ [The Bus]. Published on YouTube on September 10. 2012. https://youtu.be/acq5CGbUgfs [13.02.2016].

Midttrafik (2015): „Buskunden“ [The Passenger]. Published on YouTube on January 30. 2015. https://youtu.be/ny8r_qGb9io [13.02.2016].

Pepsi (2010): “Pepsi WC 2006 ad”. Published on YouTube on September 9. 2010. https://youtu.be/8Z6xLFEoW_A [13.02.2016].

Spies Rejser (2014): “Do it for Denmark”. Published on YouTube on March 26. 2014. https://youtu.be/vrO3TfJc9Qw [13.02.2016].

Spies Rejser (2015): “Do it for Mom”. Published on YouTube on September 29. 2015.www.youtube.com/watch?v=B00grl3K01g [13.02.2016].

Timoner, Ondi/Mizrahi, Gabriel (2014): “‘Do it for Denmark’ Encourages Danish Babymaking“. TheLipTV. Published on YouTube on April 3. 2014. https://youtu.be/bf2f31t0O80 [13.07.2015].

Thorlacius, Asbjørn (2013a): “Denmark in the Eyes of Chinese People”. Published on YouTube on July 28. 2013. www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q4teJ6K2GaU [13.07.2015].

Thorlacius, Asbjørn (2013b): „Northern Europe/Scandinavia in the eyes of Chinese People“. Published on YouTube on December 22. www.youtube.com/watch?v=qxxQMzHYmoQ [13.07.2015].

Uygur, Cenk/Kasparian, Ana (2009): „Danish Ad Banned – Are Danish Women Promiscuous?“ The Young Turks. Published on YouTube on September 16. https://youtu.be/746VnmCXD2g [13.07.2015].

Uygur, Cenk/Kasparian, Ana (2014): „Denmark Solves Birthrate Decline“. Published on YouTube on April 6. https://youtu.be/AZmO5U5fWZI [13.07.2015].

Visitdanmark (2009): „Danish mother seeking“. Published on YouTube on September 14. https://youtu.be/F8Seo5j_mNU?list=PLE67824AD38D88F90 [13.02.2016].