http://dx.doi.org/10.13092/lo.83.3787

Emotion has long been argued to be a phenomenon with human beings (Darwin 1972). Yet, the verbal expressions of emotions and the perceptions of them are claimed to vary in different cultures (Matsumoto et al. 2002). Also, it is argued that expressions of emotion cannot be considered as a universally constructed phenomenon since they are developed in response to a certain culture portraying unique social complexities (Turner/Stets 2005). Hence, social constructions and culture define and condition emotions. As Downes (2000) asserts, culture dictates what man feels and therefore the language to be used as a means of this manifestation. The expression of sympathy, which is a linguistic response to someone’s emotion of misery, is different from culture to culture (see Nakajima 2003; Matsumoto et al. 2002; Turner/Stets 2005). Hence, in certain critical situations, the appropriate verbal action of expressing sympathy is of utmost importance. Upon facing a misery, intimates get involved with some emotional sensitivities; and accordingly, expressing sympathy can have a constructive effect if offered appropriately in accordance with the cultural norms and protocols, or a destructive one if it fails to satisfy the socio-cultural expectations. Therefore, the performance of the speech act of expressing sympathy is one among such critical socio-cultural issues. As the expressions of sympathy vary in different cultures and subcultures, when expressing sympathy to interlocutors from different cultures/subcultures, speakers should respect their own norms of interaction and protect/maintain/enhance both their own and the interlocutor’s respectability face and their own and the interlocutor’s identity face (See section 2; Spencer-Oatey 2005). Hence, investigations on the realisation of the speech act of expressing sympathy in Persian is of great importance for researchers working in the field. This is what this paper targets to investigate.

Sympathy and emotion have mostly been explored from sociological (Kanov et al. 2004) and psychological (Wispé 1991) perspectives. However, in line with a growing interest in the exploration of the speech act of expressing sympathy and its significant importance, few scholars have studied it in different cultures.

In an attempt to scrutinise sympathy expressions in American culture, Clark’s (1997) study showed that sympathy is an inseparable part of Americans’ life which is not only expressed but also expected to be expressed to family members, friends and acquaintances. Moreover, Clark argues that even when strangers are suffering a misery, Americans sympathise with them. On the other hand, Clark (1997) claims that Americans are sometimes unsympathetic. American comedians, for instance, mock others’ or their own mishaps, or in sports people sometimes deride others’ defeat. She asserts that the reason for this lack of sympathy rests on Americans’ independence, and the idea that everyone is responsible for their own wellbeing. Clark further explains that it is the contextual situation in American culture which prescribes or proscribes the realisation of sympathy expressions and the way and time to express it.

In a cross-linguistic study and using written elicitation tasks and a questionnaire, Nakajima (2003) examined sympathy expressions of American college students, Japanese college students and Japanese learners of English. She concluded that sympathy expressions of the three groups vary in terms of the number of words used to sympathise. She found out that Americans use more number of words compared with Japanese learners of English, and the latter use more words compared with Japanese college students. Besides scrutinising the participants’ sympathy expressions in two situations – a more serious situation and a less serious situation – and finding some differences, Nakajima’s study shows that expressions of sympathy vary across cultures and these differences lead to misunderstanding.

Pudlinski (2005), also, explored sympathy in social support settings. He investigated ‘consumer-run warm lines’, telephone conversations between community mental health staff and callers who are in some sort of distress, and found that speakers use eight distinct sympathy strategies of 1) emotive reactions, 2) assessments, 3) naming another’s feelings, 4) formulating the gist of the trouble, 5) using an idiom, 6) expressing one’s own feelings about another’s trouble, 7) reporting one’s own reaction and 8) sharing a similar experience of similar feelings to comfort the interlocutor. She also found out that these expressions are utilised at different points during the conversation and are employed considering the three criteria of the depth of understandings of the interlocutors’ feelings and the similarity of the shared feeling as well as the speakers’ ability to lessen the emotional or physical pain.

The literature on speech act studies shows that scholars have thoroughly explored other speech acts in different languages. Sasaki’s (1998) study of EFL students’ production of speech acts, Felix-Brasdefer’s (2006) study of refusals among male speakers of Mexican English, Nureddeen’s (2008) study of apologising in Sudanese Arabic, Hassall’s (2003) study of requests among Australian learners of Indonesian, Yu’s (2003) study of compliment responses in Chinese, Garcia’s (2010) study of condolences among Peruvian Spanish Speakers, etc. are among a great number of attempts to explore speech acts in different languages and cultures. In Persian, also, speech acts of disagreement (e. g. Parvaresh/Eslami Rasekh 2009), apology (e. g. Afghari 2007; Shariati/Chamani 2010), refusal (e. g. Allami/Naeimi 2011), invitation (e. g. Eslami 2005; Salmani-Nodoushan 2006), request (e. g. Eslami-Rasekh/Tavakoli/Abdolrezapour 2010) have been explored, mostly cross-culturally. This study seeks to fill the gap of exploring speech act of expressing sympathy in Persian and contribute empirically to the body of research on speech acts in Persian language and culture.

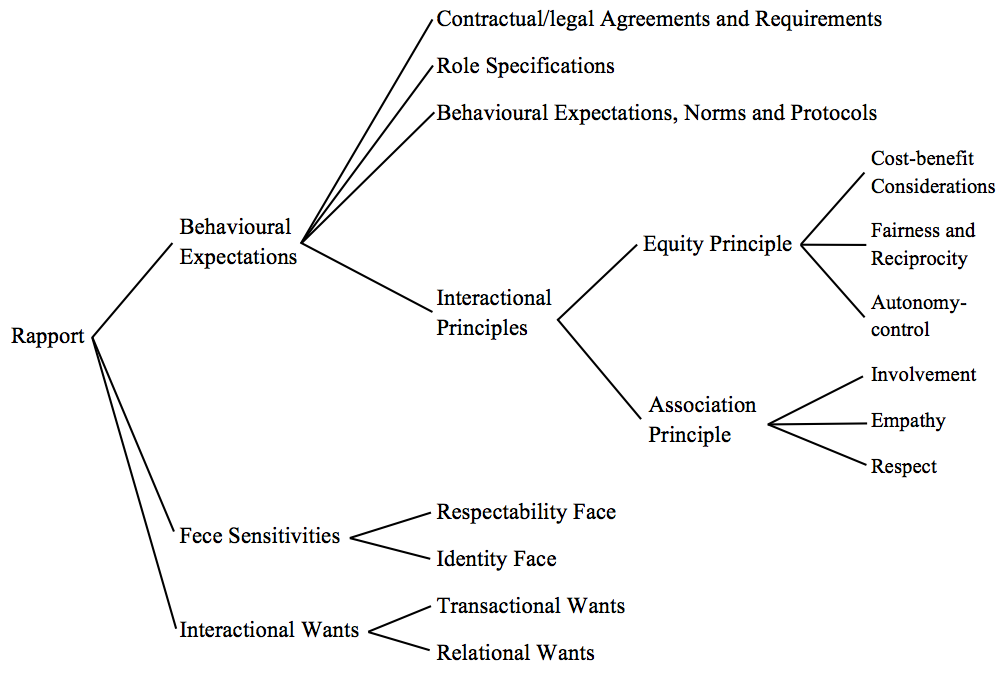

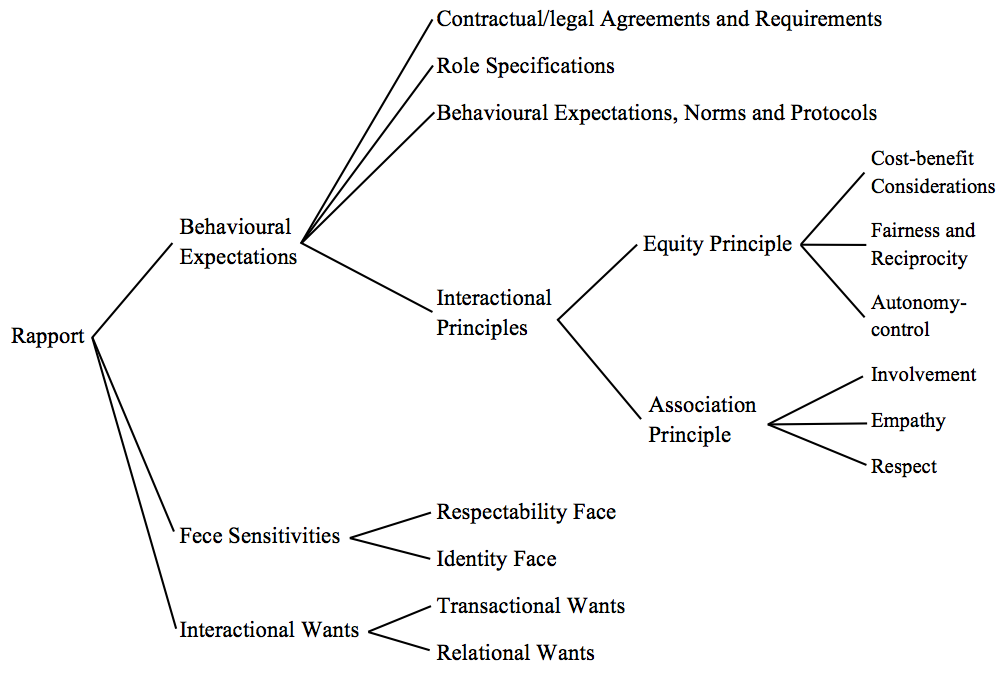

Linguists have proposed different views toward politeness. Whilst Brown and Levinson (1987) explain it in terms of face, some other scholars including Gu (1990) define it in terms of maxims. Politeness has also been explained in terms of some communicative norms (e. g. Fraser 1990 and Locher 2004). Spencer-Oatey (2000, 2002), however, goes beyond linguistic strategies as merely responses to face threatening acts. ‘Rapport management’, as she labels it, explains politeness through social relationships and explores the way these social relations are constructed, maintained or threatened in interaction (Spencer-Oatey 2000, 2002). When communicating, or within a course of interaction, people have differing types of rapport which she defines as “relations between people” (Spencer-Oatey 2000). Within the framework of rapport management, the enhanced, maintained or damaged rapport is judged based upon the three key elements of rapport; ‘behavioural expectations’, ‘face sensitivities’ and ‘interactional wants’ (Spencer-Oatey 2005).

Behavioural expectations are judgments people have about social appropriateness which lies within the realm of their beliefs about prescribed, permitted or proscribed behaviour (Spencer-Oatey 2005: 115). While Spencer-Oatey (2005) unpacks the bases of (im)politeness judgment, as outlined in figure 1, she asserts that behavioural expectations might be the result of 1) contractual/legal agreements and requirements (e. g. provisions of employment and avoidance of discriminatory behaviour), 2) role specifications (e. g. duties specified in a job contract), 3) behavioural conventions, norms and protocols and 4) interactional principles.

Behavioural conventions, norms and protocols are ritual phrases or behaviour expected in different interactions (e. g. expected rituals when expressing sympathy). Spencer-Oatey (2005) adds that these conventions exist across a range of domains; illocutionary domain (the performance of speech acts), discourse domain (the discourse content and structure of an interchange), participation domain (the procedural aspects of an interchange), stylistic domain (the stylistic aspects of an interchange, such as choice of tone) or non-verbal domain (the non-verbal aspects of an interchange, such as gestures) (Spencer-Oatey 2005: 117).

Interactional principles, on the other hand, consist of two subordinate principles; equity principle and association principle. The equity principle has three components: cost-benefit considerations (people should not be exploited or disadvantaged), fairness and reciprocity (the belief that costs and benefits should be ‘fair’ and kept roughly in balance), and autonomy-control (the belief that people should not be unduly controlled or imposed upon). The association principle has three elements: involvement (people should have appropriate amounts and types of activity involvement with others), empathy (people should share appropriate concerns, feelings and interests with others), and respect (people should show appropriate amounts of respectfulness for others) (Spencer-Oatey 2005: 118).

For the purpose the present study, when focusing on behavioural expectations, sympathy expressions of Persian cultural group would be explored in regard to behavioural conventions, norm and protocols in illocutionary and discourse domains as well as the association principle.

According to Spencer-Oatey (2005), face is either respectability or identity. Respectability face is the prestige, honour or a good name a person or social group holds and claims within a community. Identity face, on the other hand, is positive social value someone takes within a particular contact as well as the claim to social group membership and is potential to be enhanced or threatened. She states that identity face includes elements such as bodily features and control (e. g. skin blemishes, burping), possessions and belongings (material and affiliative), performance/skills (e. g. musical performance), social behaviour (e. g. sympathising), and verbal behaviour (e. g. wording of illocutionary acts, stylistic choice) (Spencer-Oatey 2005: 121–122).

Spencer-Oatey categorises interactional wants (or goals) as either transactional or interactional. She asserts that while these two goals may be interrelated, by transactional goals people attempt to reach a ‘concrete’ task; however, interactional goals target an effective relationship management (Spencer-Oatey 2005: 125).

In this study, in addition to behavioural expectations, face sensitivities and interactional wants of Persian cultural group when expressing sympathy is discussed.

Figure 1: The Bases of Rapport

To meet the objectives of the study, open role-play scenario was used to collect the data. Open role-play was utilised as the data collection instrument since it allows the interaction to be produced based upon the prompts which specify the situational context (Kasper 2008). Moreover, open role-plays make it possible for the participants to carry out complete interactions and to have maximum control over their conversational interchange (Scarcella 1979). The fruitfulness of the method is also mentioned by Felix-Brasdefer (2003) who asserts that open role-plays allow the researchers to control social variables such as power and distance and provide them with spoken discourses with high indices of pragmatic features. Moreover, open role-plays encourage participants to completely express their sympathies and respond to them for an accurate and comprehensive analysis. Open role-play was prioritised to the methods collecting naturally occurring data since within the scope of the present research, which is to study a specific type of interaction in the same context, it would be extremely difficult to collect the desired data (i. e. sympathy expressions offered to a specific person in the same context by different subjects who each have a specific set of specifications) through naturally occurring talk. Further, the sensitive nature of the situations in which a naturally occurring sympathy is offered prevented the researcher to collect naturally occurring data.

In order to cast light on the participants’ perception of the expressed sympathies and socio-cultural issues underlying them, each role-play was followed by an interview in which the researcher interviewed the subjects and the interlocutor about their verbal sympathy strategies and their suitability as well as the level of perceived politeness during the whole conversational interchange1. As Felix-Brasdefer (2003) states, participants’ verbal reports on their conception of the interactions increase the credibility of role-plays since their social perceptions of the speech act complements the role-play data. The analysis of the data collected through the interviews helped the researcher to shed light on the appropriateness of subjects’ social communicative activity of expressing sympathy and the kind of relationship built within the course of the interaction.

It should be noted that the data through role-plays and retrospective interviews was collected in Tehran, Iran.

Subjects included 24 Persian speakers who were born and lived in Iran. 12 males and 12 females ranging from 18 to 55 years of age with the mean of 34 for males and 36 for females were selected for the study. The interlocutor was a 32-year-old professional actor who was also born and lived in Iran. The subjects were chosen among the interlocutor’s friends and acquaintances and were from different walks of life in such a way as to be diverse in terms of education2 and occupation3 as well as age to have a broad population which better reflects the society of Persian Speakers. All the subjects and the interlocutor signed a consent form before participating in the study, and the interlocutor, but not the subjects, was remunerated after all the data was collected.

Conducting an online survey suggested that for 122 of 167 participants, as the representatives of Persian cultural group, health problem and car accident were the top two most sympathy demanding situations; especially for the interlocutors with solidarity4. Therefore, the situation for the role-plays was made employing an interlocutor suffering health problems due to a recent car accident and the subjects who were all the interlocutor’s close friends.

The interlocutor and subjects were first informed that they would be presented with a given situation and they were supposed to engage in a regular, spontaneous conversation which would be audio-taped. Each subject was separately given the instruction. The interlocutor was told that:

Yesterday, you had a very serious accident with considerable damage to your car and some injuries. An old colleague/classmate/teammate who is now a close friend of yours comes to the hospital to meet you. You engage in a real conversation with an initial warm greeting.

On the other hand, each subject was told that:

You are informed that an old colleague/classmate/teammate who is now a close friend had an accident with considerable damage to the car and some injuries the day before. You go to the hospital to meet and talk with him. Engage in a real conversation.

After being given the instructions, each subject and the interlocutor improvised a conversation.

The 24 tape recorded role-plays were carefully transcribed by the researcher. All the transcribed role-plays were then categorised and analysed in terms of the recurrent sympathy strategies and their reflection(s) on the speakers’ and interlocutor’s behavioural expectations, face sensitivities and the type of wants interspersed within the course of the interactions. The analysis was also based upon the data collected through the interviews with the participants after each role-play.

Upon expressing sympathy, participants used 12 distinct strategies. These expressions, as suggested by the findings of the retrospective interviews, were responses to behavioural expectations of the Persian cultural group. These sympathy expressions were categorised as 1) requesting information, 2) offering assistance, 3) expressing concern, 4) expressing surprise, 5) expressing sadness, 6) expressing understanding, 7) giving advice/suggestions, 8) acknowledging the interlocutor, 9) associating with fate, 10) expressing good wishes, 11) providing explanation and 12) teasing the interlocutor. Following is the description of these sympathy strategies provided with one example from the corpus of the study for each.

|

1) |

Requesting information: Some participants asked the interlocutor some questions about the accident and how it happened. |

|

chi shod? chejuri etefagh oftad? |

|

|

[‘What happened!? How did it happen!?’] |

|

|

2) |

Offering assistance: A group of participants offered to cooperate with the hospital as well as post-accident procedures. |

|

Khodam farda miram donbale karaye bime! |

|

|

[‘I’ll take care of insurance procedures tomorrow!’] |

|

|

3) |

Expressing concern: Participants also showed concern over the interlocutor’s health situation. |

|

alan halet khube? ax ina gerefti? |

|

|

[‘Are you OK now? Have you got X-rays and the like?’] |

|

|

4) |

Expressing surprise: A couple of participants stated their utter surprise at the accident. |

|

oh khodaye man! dari shukhi mikoni! |

|

|

[‘Oh my God! You’re kidding!’] |

|

|

5) |

Expressing sadness: Upon sympathising with the interlocutor, participants expressed their sadness at the event. |

|

na tanha man balke hame bacheha as in etefagh narahat shodan! |

|

|

[‘Not only me but also all the boys became sad at the news!’] |

|

|

6) |

Expressing understanding: Some participants expressed that they know how much pain the interlocutor is suffering from and the mental state he is experiencing due to having had the same experience in the past. |

|

mifahmam che hali dari! Parsal ke pam shekast... |

|

|

[‘I understand how you feel! Last year, when I broke my leg...’] |

|

|

7) |

Giving advice/suggestions: Participants also advised the interlocutor what to do in order to heal or lessen the pain. |

|

Say kon ab ananas bokhori! kheiliam rah naro ru pat! |

|

|

[‘Try drinking pineapple juice! And don’t walk so much on your foot!’] |

|

|

8) |

Acknowledging the interlocutor: A couple of participants acknowledged the interlocutor’s driving skill in addition to his physical power. |

|

to ke ranandegit khub bud dadash! |

|

|

[‘You have been a good driver, bro!’] |

|

|

9) |

Associating with fate: Participants also clung on some statements related to fate to justify the event and therefore sympathise with the interlocutor. |

|

daste to nabude! taghdir injuri bude! |

|

|

[‘It wasn’t in your control! It was your destiny!’] |

|

|

10) |

Expressing good wishes: Some participants expressed a wish for the interlocutor to get better soon. |

|

ishalla zudtar khub beshi azizam! |

|

|

[‘I hope you feel better soon, honey!’] |

|

|

11) |

Providing explanation: Participant found it useful to explain how they were informed of the event. |

|

Man ta dishab nemidunestam, Hamed (yek duste moshtarak) behem khabar dad! |

|

|

[‘I didn’t know until last night, Hamed (name of a mutual friend) told it to me!’] |

|

|

12) |

Teasing the interlocutor: While sympathising, some participants teased the interlocutor about his present situation. |

|

ghiyafasho negah kon! shabihe khengulaye tu kartona shode! |

|

|

[‘Look at him! He looks like those silly cartoon characters!’] |

After categorising the subjects’ sympathy expressions there was the need for a framework to analyse the strategies and shed light on the cultural concepts behind the expressions of sympathy in Persian culture. Even though most theories of politeness deal with self, rapport management focuses on self and other (Spencer-Oatey 2008: 12). Hence, in the Persian culture and specifically while analysing the speech act of expressing sympathy in Persian in which, as confirmed by the findings of retrospective interviews, both self and other are of importance, rapport management would be a proper framework. Therefore, rapport management theory has been adopted in this study to scrutinise the speech act of expressing sympathy in Persian and shed light on the behavioural expectation, face sensitivities and interactional wants within this cultural group. Following is the analysis of the strategies used by the participants in the role-plays with the conclusions been also drawn based upon the findings of the retrospective interviews within the framework of rapport management.

Within the framework of rapport management and dealing with illocutionary and discourse domains, sympathy strategies in Persian, which all show subjects’ rapport-enhancing orientation, are categorised as interactional principles and behavioural conventions, norms and protocols.

In regard to interactional principles, we argue that expressing good wishes (ishala zudtar khub beshi; meaning, ‘I hope you feel better soon’) is the only expression which falls in the category behavioural conventions, norms and protocols. This expression is a ritual phrase that is expected when people convey their expressions of sympathy. Persian cultural group look for and cling onto some good wishes to satisfy this cultural convention and if this ritual phrase in not expressed, they consider it as a deviation from the norm.

In regard to the association principle of interactional principles, we can say that all the three components of involvement, empathy and respect are respected. Requesting information, offering assistance and expressing concern are the strategies respecting involvement component since all these strategies make the speaker part of the interlocutor’s inner group. These strategies are the means by which Persian speakers make a bond with the interlocutors and encourage them to share the grief which would ultimately result in enhancing rapport. It is worth noting that although Spencer-Oatey (2005) uses the concern a teacher is showing toward his student to exemplify empathy component, findings of the retrospective interviews suggest that expressing concern while sympathising with the interlocutor is simply an attempt to make the speaker closer to the interlocutor, therefore, in this study, it is categorised as involvement component.

On the other hand, empathy components are expressing surprise, expressing sadness, expressing understanding, giving advice/suggestions, associating with fate and expressing good wishes since they are utilised to empathise with the interlocutor and share the feeling and concern for him, therefore mitigate his grief in that difficult situation.

Further, respect components in our classification are providing explanation and acknowledging the interlocutor due to the fact that they justify the speakers’ presence at the hospital and show respect toward the interlocutor. By showing respect, speakers satisfy a broader convention among Persian cultural group, which is to show sufficient amount of respect in every situation.

Participants’ answers in the retrospective interviews confirm the speakers’ demonstration of a rapport-enhancing orientation as a result of a prescribed socially appropriate behaviour in the context of the given situation.

Considering the quantitative information in table 1, the fact that empathy components play a major role (118 or 58 %) strongly supports the idea that comforting the interlocutor is of utmost importance. Involvement components and respect components are also respected with 64 (or 32 %) and 20 (or 10 %), respectively. The information reinforces the claim that in Persian, in the situation of sympathising an interlocutor with solidarity, while the speakers’ first concern is comforting the interlocutor, engaging in the interlocutors’ inner bond is prioritised to respecting them. Through engaging in the interlocutor’s inner bond, i. e. respecting envelopment components, speakers make themselves closer to the interlocutor, therefore make the sympathy expressions more forceful.

Regarding violations, we claim that giving advice/suggestions is a violation of the autonomy-control component of the equity principle since it suggests the superiority of the speaker (DeCapua/Huber 1995; Wardhaugh 1985). However, we argue that although conveying such an idea, findings of the retrospective interviews, in line with Bayraktaroglu (2001), show that giving advice/suggestions is a means to show concern for the interlocutor and empathise with him.

|

male |

female |

TOTAL |

|||||

|

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

||

|

Involvement Component |

Requesting information |

10 |

10 |

8 |

8 |

18 |

9 |

|

Offering assistance |

16 |

16 |

7 |

7 |

23 |

11 |

|

|

Expressing concern |

8 |

8 |

15 |

14 |

23 |

11 |

|

|

SUBTOTAL |

34 |

35 |

30 |

29 |

64 |

32 |

|

|

Empathy Component |

Expressing surprise |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

6 |

3 |

|

Expressing sadness |

9 |

9 |

16 |

15 |

25 |

12 |

|

|

Expressing understanding |

10 |

10 |

6 |

6 |

16 |

8 |

|

|

Giving advice/suggestion |

9 |

9 |

6 |

6 |

15 |

7 |

|

|

Associations with fate |

8 |

8 |

9 |

9 |

17 |

8 |

|

|

Expressing good wishes |

18 |

18 |

21 |

20 |

39 |

19 |

|

|

SUBTOTAL |

57 |

58 |

61 |

59 |

118 |

58 |

|

|

Respect Component |

Acknowledging the interlocutor |

4 |

4 |

7 |

7 |

11 |

5 |

|

Providing explanation |

3 |

3 |

6 |

6 |

9 |

4 |

|

|

SUBTOTAL |

7 |

7 |

13 |

13 |

20 |

10 |

|

|

TOTAL |

98 |

100 |

104 |

100 |

202 |

100 |

|

Table 1: Association Principle

In order to analyse face sensitivities, strategies are categorised in two classes; face-enhancing strategies, and face-threatening strategies. Requesting information, offering assistance, expressing concern, expressing surprise, expressing sadness, expressing understanding, giving advice/suggestions, acknowledging the interlocutor, association with fate, expressing good wishes and providing explanation are the strategies that enhance face. On the other hand, teasing the interlocutor threatens face. It could be argued that albeit teasing the interlocutor is a face threatening strategy, as confirmed by the findings of the retrospective interviews, it is a permitted behaviour in the Persian culture since the strategy is a means by which speakers try to make the interlocutor forget the bad situation and make him laugh. As another approach to discuss the strategy, considering the retrospective interviews after the role-plays in which the strategy was used, the interlocutor also commented that although the strategy is a permitted behaviour in the Persian culture, he sometimes did not feel comfortable with it and tried to shift the conversation toward a more desirable path. Moreover, as confirmed by the quantitative information presented in table 2 which shows that 273 or 98 % of the strategies are face-enhancing and 5 or 2 % of them are face-threatening, he added that the negative effect the expression had was obliterated by the intensive use of other compensating (face-enhancing) strategies.

It is argued here that face in our classification is both identity and respectability. In the contexts of the study and when expressing sympathy, face can be either enhanced or threatened (identity face). If sympathy expressions are offered in accordance with the norms and protocols, interlocutors’ face in enhanced. On the other hand, if speakers deviate from any convention and norm, interlocutors’ face is threatened. Face, also, contributes to judgments of an adequate and appropriate behaviour (respectability face). Persian speakers judge their interlocutors based upon the degree to which appropriate expressions of sympathy is offered.

It is worth noting that by face we address both interlocutor’s and speakers’ face. As Markus/Kitayama (1991: 229) state, by promoting the goals of others, one’s own goals will also be observed by the person with whom one is interdependent. Hence, through speakers enhancing/threatening the interlocutor’s face, their own face is also enhanced/threatened.

|

male |

female |

TOTAL |

|||||

|

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

||

|

Enhancing Face |

Requesting information |

10 |

10 |

8 |

8 |

18 |

9 |

|

Offering assistance |

16 |

15 |

7 |

7 |

23 |

11 |

|

|

Expressing concern |

8 |

8 |

15 |

14 |

23 |

11 |

|

|

Expressing surprise |

3 |

3 |

3 |

3 |

6 |

3 |

|

|

Expressing sadness |

9 |

9 |

16 |

15 |

25 |

12 |

|

|

Expressing understanding |

10 |

10 |

6 |

6 |

16 |

8 |

|

|

Giving advice/suggestion |

9 |

9 |

6 |

6 |

15 |

7 |

|

|

Associations with fate |

8 |

8 |

9 |

8 |

17 |

8 |

|

|

Expressing good wishes |

18 |

17 |

21 |

20 |

39 |

19 |

|

|

Acknowledging the interlocutor |

4 |

4 |

7 |

7 |

11 |

5 |

|

|

Providing explanation |

3 |

3 |

6 |

6 |

9 |

4 |

|

|

SUBTOTAL |

98 |

94 |

104 |

98 |

202 |

96 |

|

|

Threatening Face |

Teasing the interlocutor |

6 |

6 |

2 |

2 |

8 |

4 |

|

SUBTOTAL |

6 |

6 |

2 |

2 |

8 |

4 |

|

|

TOTAL |

104 |

100 |

106 |

100 |

210 |

100 |

|

Table 2: Face Sensitivities

The data in this paper supports the fact that interactional goals (wants) are strongly relational due to the fact that all the strategies used by the speakers are merely used to make a strong relationship with the aim of improving their inner bond. No transactional goal is observed since the data does not include any strategy aiming at achieving a concrete task. The argument is also supported by the subjects’ and the interlocutor’s responses in the retrospective interviews which all showed the subjects’ relational goal during the whole interaction. Furthermore, the interlocutor also claimed that the subjects’ relational wants were evident in all the interactions. It shows that while sympathising in Persian, speakers have merely building and/or protecting a favorable relationship in prospect which would ultimately enhance their rapport.

It can be argued that, as also confirmed by the findings of the retrospective interviews, the strategies presented and discussed above describe the Persian culture, in the given context of the study, as the one in which establishing, maintaining and enhancing rapport, i. e. in-group relationship, is valued. In the same vein, Kağitçibaşi (1996) also labels such a culture as the culture of ‘relatedness’. Moreover, the strategies and results reflect interdependent self-construals of self within which the focus is on showing sympathetic concern and emphasising collective welfare for others (Markus/Kitayama 1991: 228).

Furthermore, analysis of the data has shown that the subjects as a whole exhibited a rapport-enhancing orientation using strategies that showed respect toward the association and equity principles. It was argued that this orientation is the prescribed behaviour within the context of the situation with solidarity between the subjects and the interlocutor while the latter had a car accident and is experiencing some sort of health problem. Concerning participants’ respect for their face sensitivities, we can see that the participants enhanced the interlocutor and their own identity and respectability face. Face violation was occasionally observed. Participants’ interactional wants were strictly relational, which maintained and finally enhanced in-group harmony.

The interlocutor’s responses throughout the interactions and the subjects’ and the interlocutor’s answers in the retrospective interviews after the role-plays support the argument that the subjects exhibited permitted behaviour since neither the interlocutor complained about her privacy being threatened nor the subjects admitted such a violation.

Findings of the present study can be used to shed light on the Persians’ communicative expectations and behaviours which can benefit intercultural communications. Furthermore, the implications can also be fruitful in teaching Persian to speakers of other languages, enriching their pragmatic competence.

Needless to say the findings in this study cannot be generalised to the behaviour of all Persian speakers expressing sympathy to all interlocutors since this study merely targeted the expressions of sympathy when sympathising with the interlocutors of no social distance. Moreover, further studies on the realisation of different types of expressives when pain or bad news is expressed by Persians of different social classes, age, religions and/or in different situations will help us better understand Persians’ preferred management of rapport.

Afghari, Akbar (2007): “A sociopragmatic study of apology speech act realization patterns in Persian”. Speech communication 49/3: 177–185.

Allami, Hamid/Naeimi, Amin (2011): “A cross-linguistic study of refusals. An analysis of pragmatic competence development in Iranian EFL learners”. Journal of Pragmatics 43/1: 385–406.

Bayraktaroglu, Erin (2001): “Advice-giving in Turkish. ‘Superiority’ or ‘solidarity’?”. In: Bayraktaroglu, Erin/Sifianou, Maria (eds.): Linguistic Politeness across Boundaries. The Case of Greek and Turkish. Amsterdam/Philadelphia, Benjamins: 177–208.

Brown, Penelope/Levinson, Stephen C. (1978): Politeness. Some universals in language usage. Cambridge etc.: Cambridge University Press.

Clark, Candace (1997): Misery and company. Sympathy in everyday life. Chicago/London: University of Chicago Press.

Darwin, Charles Robert (1872): The expression of the emotions in man and animals. London: John Murray.

DeCapua, Andrea/Huber, Lisa (1995): “‘If I were you...’. Advice in American English”. Multilingua 14/2: 117–132.

Downes, William (2000): “The language of felt experience. Emotional, evaluative and intuitive”. Language and Literature 9/2: 99–121.

Eslami-Rasekh, Abbass/Tavakoli, Mansoor/Abdolrezapour, Parisa (2010): “Certainty and Conventional Indirectness in Persian and American Request Forms”. The Social Sciences 5/4: 332–339.

Eslami, Zohreh R. (2005): “Invitations in Persian and English. Ostensible or genuine?”. Intercultural Pragmatics 2/4: 453–480.

Felix-Brasdefer, César (2003): “Validity in data collection methods in pragmatic research”. In: Kempchinsky, Paula/Piñeros, Carlos-Eduardo (eds.): Theory, Practice, and Acquisition. Papers from the 6th Hispanic Linguistics Symposium and the 5th Conference on the Acquisition of Spanish and Portuguese. Somerville, Cascadilla: 239–257.

Felix-Brasdefer, César (2006): “Linguistic politeness in Mexico. Refusal strategies among male speakers of Mexican Spanish”. Journal of Pragmatics 38/12: 2158–2187.

Fraser, Bruce (1990): “Perspectives on politeness”. Journal of pragmatics 14/2: 219–236.

García, Carmen (2010): “‘Cuente conmigo’. The expression of sympathy by Peruvian Spanish speakers”. Journal of Pragmatics 42/2: 408–425.

Gu, Yueguo (1990): “Politeness phenomena in modern Chinese”. Journal of pragmatics 14/2: 237–257.

Hassall, Tim (2003): “Requests by Australian learners of Indonesian”. Journal of Pragmatics 35/12: 1903–1928.

Kağitçibaşi, Ciğdem (1996): “Cross-cultural psychology and development”. In: Pandey, Janak/Sinha, Durganand/Bhawuk, Dharm P. S. (eds.): Asian Contributions to Cross-cultural Psychology. New Delhi/Thousand Oaks/London, Sage: 42–49.

Kanov, Jason M. et al. (2004): “Compassion in organizational life”. American Behavioral Scientist 47/6: 808–827.

Kasper, Gabriele (2008): “Data collection in pragmatics research”. In: Spencer-Oatey, Helen (ed.): Culturally Speaking. Culture, Communication and Politeness Theory. London/New York, Continuum: 279–303.

Locher, Miriam A. (2004): Power and politeness in action. Disagreements in oral communication. Berlin/Boston: de Gruyter. (= Language, Power and Social Process 12).

Markus, Hazel R./Kitayama, Shinobu (1991): “Culture and the self. Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation”. Psychological review 98/2: 224–253.

Matsumoto, David et al. (2002): “Cultural influences on the expression and perception of emotion”. In: Gudykunst, William B./Mody, Bella (eds.):Handbook of international and intercultural communication. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks/London/New Delhi, Sage: 107–125.

Nakajima, Keiko (2003): “The key to intercultural communication. A comparative study of speech act realization of sympathy/empathy”. Dissertation Abstracts International, A: The Humanities and Social Sciences 63/10: 3536-A.

Nureddeen, Fatima Abdurahman (2008): “Cross cultural pragmatics. Apology strategies in Sudanese Arabic”. Journal of pragmatics 40/2: 279–306.

Olshtain, Elite/Cohen, Andrew (1983): “Apology. A speech act set”. In: Wolfson, Nessa (ed.): Sociolinguistics and language acquisition. Rowley, Newbury House: 18–35.

Parkes, Collin Murray/Laungani, Pittu/Young, Bill (1997): “Culture and religion”. In: Parkes, Collin Murray/Laungani, Pittu/Young, Bill (eds.): Death and bereavement across cultures. London/New York, Routledge: 10–23.

Parvaresh, Vahid/Eslami, Abbas Rasekh (2009): “Speech act disagreement among young women in Iran”. CLCWeb. Comparative Literature and Culture 11/4. doi: 10.7771/1481-4374.1565.

Pudlinski, Cristopher (2005): “Doing empathy and sympathy. Caring responses to troubles telling on a peer support line”. Discourse Studies 7/3: 267–288.

Salmani-Nodoushan, Mohammad Ali (2006): “A comparative sociopragmatic study of ostensible invitations in English and Farsi”. Speech Communication 48/8: 903–912.

Sasaki, Miyuki (1998): “Investigating EFL students’ production of speech acts. A comparison of production questionnaires and role plays”. Journal of pragmatics 30/4: 457–484.

Scarcella, Robin (1979): “On speaking politely in a second language”. In: Yorio, Carlos A./Perkins, Kyle, Schachter/Jacqueline (eds.): On TESOL ’79. The Learner in Focus. Washington/DC, Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages: 275–287.

Shariati, Mohammad/Chamani, Fariba (2010): “Apology strategies in Persian”. Journal of Pragmatics 42/6: 1689–1699.

Spencer-Oatey, Helen (ed.) (2000): Culturally speaking. Managing rapport through talk across cultures. London: Continuum.

Spencer-Oatey, Helen (2002): “Managing rapport in talk. Using rapport sensitive incidents to explore the motivational concerns underlying the management of relations”. Journal of Pragmatics 34/5: 529–545.

Spencer-Oatey, Helen (2005): “(Im)politeness, face and perceptions of rapport. Unpackaging their bases and interrelationships”. Journal of Politeness Research 1/1: 113–137.

Spencer-Oatey, Helen (ed.) (2008): Culturally Speaking. Culture, Communication and Politeness Theory. London/New York: Continuum.

Turner, Jonathan H./Stets, Jan E. (2005): The sociology of emotions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wardhaugh, Ronald (1985): How Conversation Works. Oxford: Blackwell.

Wispé, Lauren (1991): The psychology of sympathy. New York/London: Plenum.

Yu, Ming-chung (2003): “On the universality of face. Evidence from Chinese compliment response behavior”. Journal of pragmatics 35/10–11: 1679–1710.

1 Questions like Do you think your interaction was polite enough? Why/Why not?, How do you judge the interlocutor’s and your own words?, Why did you use (a sympathy strategy or response)?, etc. were asked in the interviews. back

2 Ranging from high school diploma to PhD holders. back

3 Including caretakers, salespersons, homemakers, clerks, film directors and university professors. back

4 Close friends and relatives as well as family members. back