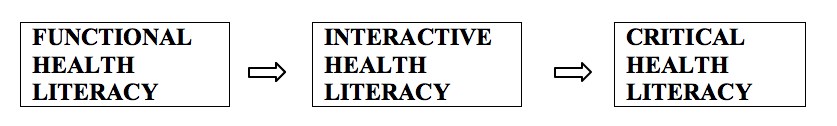

Fig 1: Continuum of Health Literacy

Everyday, language users interact in order to perform certain functions, which include socialization, getting information and passing on information. Over the years, discourse analysts have been analyzing the structure and function of different kinds of discourse in order to discover the interactants' internalized rules of the language, their experience, and cultural and social context of language use. They have also been looking at how these affect what they say and how they say it.

A major goal of any communicative events such as campaigns, instructions and all discourses with directive functions is a change in behaviour of the participants. This goal may not be achieved if the participants involved do not understand and internalize the content of the message. The main thrust of this paper is to examine the discourse acts used in antenatal clinic literacy classes, (a genre of medical discourse), in south-western Nigeria and the overall effects of the use of these acts on the expectant mothers' comprehension and subsequent behaviour.

Adequate literacy programmes on maternal care for expectant mothers is very essential, since inadequate information on preparations for pregnancy, labour, delivery and baby care may result in medical complications for mothers during pregnancy, childbirth and delivery. This paper looks at how child birth educators in Nigeria conduct antenatal literacy classes, what they communicate, and how they communicate it, the responses of the expectant mothers and how all these affect the success of the entire communicative event.

The term 'medical discourse' is an umbrella name for any form of discourse that takes place within the medical context, usually in hospitals and other health institutions. It includes the kind of discourse that takes place between doctors and patients in the process of trying to diagnose or treat the latter's illnesses during consultations, regular health check-ups, doctors ward round. It also includes health literacy, medical classroom interactions, and so forth.

Medical encounters have been investigated from the perspective of doctor-patient exchanges, or what some scholars call 'clinical interviews'. Such studies date back to the work of Coulthard/Ashby (1976); Labov/Fanshel (1977). Other contemporary studies of medical encounters using the frameworks of ethnomethodology and conversational analysis are Drew et al. (2001); Manning/Ray (2002); Campion/Langdon (2004); Robinson (2000); Ainsworth-Vaughn (1995); Roberts/Paden (2001); Coupland et al. (1994); Gulich (2003); Heritage/Robinson (2006). Others using the framework of discourse analysis and pragmatics of discourse include Adegbite/Odebunmi (2006); Heartfield (1996); Odebunmi (2005, 2006), and so forth.

Some other studies examine the encounters between patients and nurses (Crawford et al. 1998); patients and physiotherapists (Ballinger et al. 1999), patients and pharmacists (Pilnick 1999) and patients and occupational therapists (Mattingly 1994). All these studies examine the contexts and patterns of the discourse and the roles of the participants in the discourse.

The present study examines a sub-genre of health literacy discourse - the antenatal literacy class. The goals of the institution are to equip expectant mothers with the knowledge of how to cope with pregnancy and be in good health and the skills for taking care of their babies after birth.

Health literacy is any form of education geared towards helping people to achieve the ideal health behaviours. Such education involves ones that help patients to read and comprehend medical prescriptions, appointment slips, consent forms, inscriptions on medication and other basic health information materials. It also involves maternal health literacy. Citing the World Health Organisation, Renkert/Nutbeam (2000) defines literacy as follows:

They propose a continuum of health literacy, which includes 'functional' health literacy (one which enables the beneficiaries to function effectively in the society by increasing their participation in health programmes), communicative/interactive health literacy (one which does not only make the beneficiaries to function in the society, but also places them in the position to interact with and influence the society by passing across the message) and critical health literacy (one that makes the beneficiaries to question, evaluate, and criticize in order to change policies where necessary). They are represented in the diagram below.

Fig 1: Continuum of Health Literacy

The continuum suggests that "the different levels of literacy progressives allow for greater autonomy in decision making and personal empowerment demonstrated through the actions of individuals and communities" Renkert/Nutbeam (2000: 49). The goal of every health literacy programme should be the development of the skills and confidence needed to make choices that will improve individual health outcomes. The ultimate level of health literacy - critical health literacy will be reached when an individual has the ability to seek out information, assess the readability of such information and use the information to exert greater control over the determinants of health, and make well-informed health choices (see Renkert/Nutbeam 2000).

Antenatal health literacy is an aspect of health literacy that has received very little research attention among linguists. Most of the existing studies on it were carried out by health sociologists, public health, health literacy and nursing science experts (see Renkert/Nutbeam 2000; Zobel 2002; Gilkison 1991; Zwelling 1996; Nolan 1997).

The kind of antenatal education we are examining is formal and is usually organized in classes during expectant mothers' visits to antenatal clinics. The goal of such classes is to provide pregnant women with the necessary information and skills needed for a successful pregnancy and childbirth. Such classes focus on those things expectant mothers need to do to secure their health and that of the foetus. These include the kind of diet they should take, the kind of exercises they need to do and the drugs they need to take. Interactions in the antenatal classes are aimed at the health security of the expectant mothers and their foetus. This underscores the reason why linguists, particularly, discourse analysts should examine the features of the discourse with a view to ensure that effective communication takes place. This paper examines how the teacher and students in antenatal classes in Nigeria use language through their choice of discourse acts and how this facilitates or impedes communication in the class.

Antenatal classes are organized in hospitals and health centres for pregnant women to intimate them with the necessary health information needed in pregnancy and post-natal period. The classes are organized by nurses and midwives to educate the women on pregnancy, labour and basic baby care skills. Sometimes, other medical experts, such as physiotherapists, nutritionists and gynaecologists are invited to talk on specific issues, such as posture, exercise, diet, stages in foetus development, and so forth. Classes are organized to coincide with the days the women visit the hospital for their clinics.

A major feature of antenatal class is the health talk session, which can be likened to a classroom lesson. The nurses and midwives assume the role of the teacher and the expectant mothers that of students. Health talks focus on the basic health needs of the pregnant women, such as hygiene, balanced diet, appropriate use of drugs, exercises, natal customs and practices (Salami 2004: 3)

A typical class starts with a prayer, which could be led by the instructor or one of the pregnant women nominated by the instructor. After this, the entire class may be led to sing. Such songs are usually about domestic hygiene, nutrition, breast-feeding, immunization and so forth. Most of the songs are composed choosing the tunes of existing songs, while the lyrics are specifically chosen to reflect the thematic peculiarities of the lesson being taught. The idea of choosing tunes of existing songs is to make the learning of the songs easy for the women. In order to make a typical class lively, the women are enjoined to accompany their songs with clapping and dancing.

Antenatal classes are characterized by instructions from the nurses and midwives. In the course of this, instructors educate the class by talking extensively on the issue being addressed, illustrating where necessary and seeking feedback to ensure that they are passing across the needed information. A typical antenatal class environment is full of diagrams, which address what the medical science requires the expectant mothers to do in pregnancy, such as the pictures of the kind of diet they are expected to take, their posture in pregnancy and proper hygiene in pregnancy. In the course of the talk, the instructors solicit feedbacks by asking questions and encouraging the women to ask questions and contribute. Sometimes, the experienced mothers are encouraged to share their experience during some earlier pregnancies so that the first timers can learn from them.

The language used in a typical south-west hospital or health center is Yoruba, which is the predominantly spoken language in that part of the country. This is meant to carry along the mothers who are not literate in English as well as those who have little education and who would feel more comfortable being addressed in their mother tongue. There is also an assumption that most expectant mothers in the south-western Nigeria speak and understand Yoruba. This assumption is not always true because there are non-Yoruba speaking mothers, who because of this assumption try as much as possible to learn the language for instrumental and integrative purposes.

The data for this study were randomly selected from series of data recorded during some antenatal classes in some selected hospitals in Ile-Ife and its environs, all in south-western Nigeria. Overall twenty antenatal classes were visited and the researchers observed and recorded the discourse, but for the purpose of this paper, three different class sessions were randomly selected and analyzed based on the observation that the patterns of interaction were similar in the classes. An average class has 30 pregnant women and the teachers were different on each occasion. The teachers were typically the nurses on duty on the antenatal clinic days. Each class lasts for between forty-five minutes to one hour

Apart from the tape recordings of the classroom sessions, one of the authors was present in all the classes to observe the structure and direction of discourse. She also took observational notes of some of the verbal and non-verbal behaviours of the participants. The data, though originally recorded in Yoruba, were later translated into English for the purpose of this study. The data were analyzed using insights from studies on Discourse Analysis, particularly classroom discourse. Our focus in the data was the kinds of discourse act used by both the childbirth educators and the expectant mothers.

Literacy classes in antenatal clinics are formally organized to impart knowledge and skills on how to manage pregnancy and childbirth. In the sense that knowledge is formally imparted by teachers to some learners, it resembles classroom discourse. The nurses and midwives, just like teachers in the classroom have accepted the responsibility for the direction of the discourse. They determine what topic to speak on, how long to speak, who speaks, when they speak, and so forth.

Two of the oldest studies on classroom discourse are Barnes (1969) and Flanders (1970). Barnes examines language in the secondary classrooms by looking at two aspects of interaction - pupils' participation and teachers' question. Barnes notes that pupils' participation was too low and that there was a predominance of factual questions over reasoning ones in the three arts lessons investigated (see Sinclair/Coulthard 1975: 94). Flanders studies control and development of topics in classroom discourse and identifies three categories of behavioural types: teacher talk, pupil talk and silence.

Sinclair/Coulthard (1975) has been the strongest effort to actually implement Halliday's ideas in a well-grounded descriptively adequate theory of discourse (Malouf 1995: 1). Their work was based on Halliday's (1961) work on scale and category. They see discourse as a level of language higher than grammar. They proposed a five unit rank scale of discourse based on classroom interaction, namely: lesson, transaction, exchange, moves and acts. Lesson is the highest unit of the discourse rank scale and it refers to everything that takes place in the classroom from the point the teacher enters till he leaves. The structure of the lesson is determined by some factors, such as pupils' responses and teachers' ability to respond to pupils' responses. Transaction is next to lesson in the discourse rank scale. It is the basic unit of interaction, which consists of minimal contribution made by two participants in the discourse. It usually takes off with an opening and ends with a closing, which are typically greetings. An exchange is the whole dialogue or discussion. It is the fundamental unit that realizes social interaction. The structure of a typical exchange is IRF (where I = Initiation, R = Response and F = Follow-up). This means that the teacher initiates an exchange, the pupils respond and the teacher gives the feedback (Sinclair/Coulthard 1975: 21). Move has a function relating to the progression of the conversation.

Discourse Acts, which is our concern in this work, is the smallest unit in the discourse stratum. It has no structure except one goes below the level of discourse. According to Sinclair/Coulthard (1992),

Acts are defined principally by their functions (Coulthard 1977: 104). Sinclair and Coulthard identify 22 discourse acts, Olateju (1998), in analyzing discourse in the ESL classroom in Nigeria, identified 24 classes of act. Strenstrom (1994) differentiates between three different kinds of acts - primary acts, secondary acts and complementary acts. A primary act is the only obligatory act in a move. A secondary act accompanies primary acts by adding emphasis or further information to the primary act, for example emphasizer, expand, justify, meta-content, precursor and preface. Complementary acts accompany primary and secondary acts. They are mainly interactional and are low in informational content, eg: 'well', 'em', 'you know', etc.

Olateju (1998), also concerned with the function of utterances in ESL classrooms, adopted some of Sinclair/Coulthard's categories, but introduced others, which she identified as being peculiar to ESL classroom discourse. One of the categories - hearing check (h/c), which is realized by words such as 'hen', 'abi' (Yoruba expressions for 'is it so?') or sentences in local languages, which are meant to check whether the pupils are following the teacher or not.

The present study adopts a synthesis of the categories of discourse act identified in the studies earlier discussed in order to arrive at the types identified in the data.

The data elicited from the antenatal classes were observed for occurrences of the categories of discourse act peculiar to them. The first step was to identify the discourse acts. The discourse acts were identified by examining the turns to which these acts were closely associated and identifying their functions, noting that discourse acts are defined mainly by their functions. We also considered both the linguistic and non-linguistic contexts of utterances before indicating the acts that the utterances realize. In presenting the data, we numbered the turns using I to represent the instructor and M to represent the expectant mothers' turns.

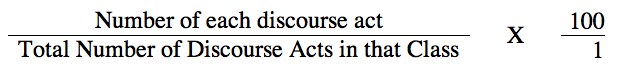

After identifying the discourse acts, we then state the total number that occurred in each class (Class A, Class B and Class C), and then the number of occurrences of the different categories (directive, informative, elicitation, etc) in that class. The percentage scores for each of the discourse acts identified in each class was calculated using the formula:

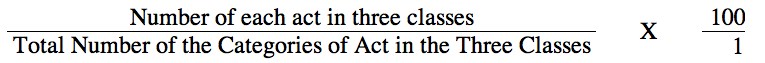

Then, we calculated the percentage scores for each acts in the three classes, using the formula:

The tables below show the analyses:

| 1 | Accept | ||||||

| 2 | Additive | ||||||

| 3 | Bid | ||||||

| 4 | Causative | ||||||

| 5 | Comment | ||||||

| 6 | Contrastive | ||||||

| 7 | Demonstration | ||||||

| 8 | Directive | ||||||

| 9 | Elicitation | ||||||

| 10 | Evaluation | ||||||

| 11 | Expatiate | ||||||

| 12 | Frame | ||||||

| 13 | Focus | ||||||

| 14 | Hearing/Check | ||||||

| 15 | Illustration | ||||||

| 16 | Informative | ||||||

| 17 | Nomination | ||||||

| 18 | Prompt | ||||||

| 19 | React | ||||||

| 20 | Repetition | ||||||

| 21 | Reply | ||||||

| 22 | Re-state | ||||||

Table 1: Discourse Acts, Occurrences and Percentages in Classes A, B and C

| Accept | ||

| Additive | ||

| Bid | ||

| Causative | ||

| Comment | ||

| Contrative | ||

| Demonstration | ||

| Directive | ||

| Elicitation | ||

| Evaluation | ||

| Expatiate | ||

| Frame | ||

| Focus | ||

| Hearing/Check | ||

| Illustration | ||

| Informative | ||

| Nomination | ||

| Prompt | ||

| React | ||

| Repetition | ||

| Reply | ||

| Re-state | ||

| TOTAL |

Table 5: Discourse Acts and Overall Percentages in Classes A, B and C

Patterns of use of discourse acts differ in the three classes as we can see in Tables 1, 2 and 3. In Class A, the discourse act with the highest number of occurrence is elicitation (note that elicitation and reply go together, i.e., an elicitation will normally be followed by a reply), while in Class B, it is informative and in Class C, it is directive (note that directive and react go together in the sense that a directive will normally be followed by a react). The dominant patterns reflect the different styles of the instructors in the classes, as they were different people. The one who handled Class A asked more questions than she did other things. The instructor of Class B provided a lot of information, while that of Class C concentrated on making the class to do things.

Overall, as presented in table 4, there were more informative discourse acts than any other category. Moreover, all the informative acts were teacher inform. This indicates that the antenatal educators in the clinics visited dominated the discourse. Instructors determine the direction of the discourse, since the class is structured to allow the instructor (the knower) to pass across some information to the pregnant women (the non-knower). According to McCarthy (1991), "this is sometimes expected in any formally and tightly-structured discourse, which is generally designed to be controlled by one party who provides information" (p. 22). It is however not the ideal thing to do if the teachers took into consideration the fact that there should be room for feedback from the students. This assumption that the teacher is the knower and the students the non-knower, should not be carried too far in the kind of discourse we are dealing with here because the pregnant women come from different backgrounds and some of them may be quite knowledgeable on the topic being discussed.

The three most prominent categories of discourse act in the data - informative, elicitation and directive show that the antenatal educators were more active in the classes than the students. They maximized the use of their power in discourse, which gives them the [+ HIGHER] role. They therefore had the privilege to talk while the mothers listened, ask the mothers to talk or act only when they (the educators) desired, and in a particular way, ask the mothers to do things and so on (Berry 1987). This also means that the expectant mothers were passive during lessons. Their perception of their role in the discourse is that of listeners. There was no single occurrence of student-inform (an instance in which students inform the class about something they know). This creates the impression that only the instructor had anything to pass across, since the instructor is the one to educate. However, instructors in antenatal discourse occupy the higher role because they are experts in the field of natal practice. This makes them according to Berry's (1987) proposition [+ PRIMARY KNOWER], i.e.: people knowledgeable in the general field and not necessarily [+ primary knower], i.e.: people knowledgeable in specific or peculiar natal issues. Pregnant women have experiences peculiar to them, which may not necessarily be addressed in the classroom by the teachers. These experiences should be shared in the antenatal classroom if they are given the opportunity. This makes it imperative for both types of primary knowers to interact in order to enrich one another's knowledge. It means in reality, the teacher and the students are knowledgeable in one way or another.

It is also possible that the composition of the classes may be responsible for the low participation of the pregnant women - the classes comprise of mothers with different levels of education, therefore, different attitudes to and aptitudes for learning. For the ones with little or no education, 'the instructor knows it all', and all they needed to do was to listen to whatever the instructor had to pass across. But for most of the well-educated ones, though they have some residual knowledge of some of the topics due to their education, they still saw themselves as captive audience, who were being compelled to listen because of the overbearing influence of the instructors in the course of the lesson. Therefore, they had little motivation to respond to what they heard.

Directive is next to informative act in terms of the number of occurrences. Directives, as observed earlier, request non-linguistic response (rea). Just like the informative act, all the directive acts found in the data were used by the instructors. This shows the extent of their power in the discourse. Some extracts of directive acts from the data are shown below:

| EX.1: | 010.

011. |

I:

M: |

Now, let us sit down... Can we clap for ourselves (dir)

(They sit down and clap) (rea) |

| EX.2: | 004. 005. 006. 007. |

I: M: I: M: |

Now,

Let us stand up. (dir) (reluctant to get up) (rea) Ha! You don't want to stand up to sing. You know we always sing whenever we come together like this. We will also sing today. (prm) Now, let us get up. (dir) (they stand up) (rea) |

| (See Appendix 2) | |||

Looking at the patterns of these directives, one can conclude that they were just strategies to carry the mothers along in the discourse and engage them in some forms of exercises in the course of the discourse.

Elicitation acts were well used in the classes. Out of the 33 elicitation acts, in the data, only three were student-elicit (an instance in which students ask questions or make enquiries on something that is not clear to them). This indicates that the classes were not interactive, since virtually all the requests for verbal responses were made by the instructors. It was also found out that most of the elicitation acts elicit obvious factual and open questions, which do not require reasoning. Responses were typically chorus answers, showing the obvious nature of the questions. Below are some of the extracts of the elicitation acts by the instructors:

| EX.3: | 014. 015. |

I: M: |

...Can you see them? (elc) Yes. (chorus answer) (rep) |

| EX.4: | 026. 027. |

I: M: |

When a woman gives birth to a child, who does the child first see? (elc)

The mother. (chorus answer) (rep) |

| EX.5: | 028. 029. |

I: M: |

...If your baby is neat, won't people want to carry it? (elc) They will. (chorus answer) (rep) |

| (See Appendix 2) | |||

This is evidence of the simplicity of the answers as shown in the chorus answers given by the expectant mothers. The elicitations did not stimulate any thinking in the students. The questions look more like those constructed just to check if the listeners were still with the speaker and not ones meant to check the listeners' understanding of what was being presented. This elicitation technique may be appropriate for learners at lower levels of education, where rote learning is normally encouraged, because they may not have the same intellectual capacity the adults have to respond to reasoning questions.

The fairly high number of comments (24: 7.14%) and hearing/check (22: 6.54% ) shows that teachers made some efforts to ensure that they were well understood by the expectant mothers. Teachers readily used comments in order to provide additional information. They also checked from time to time to ensure that their students were following the flow of discourse after talking for a long time. It was observed that many of the expectant women were not too keen on the lessons. For many of them, especially the well-educated ones there are alternative sources of information, such as books and the Internet.

It was also observed that the level of active participation of mothers generally in the classes was very low. They rarely talked and this explains the low percentage of bid (2: 0.59%). Bid is meant to signal the desire of the student to contribute. In fact, there were two occurrences of bid, and these featured in class A, while it was not used at all in the other two classes.

Demonstration and illustration were also used to enhance visual experience and reinforce the retention of the message. The expectant mothers responded positively to these acts because they made the classes lively and the message content less abstract.

Going by the findings, to a great extent, antenatal classroom discourse is similar to the conventional school classroom discourse in terms of the formality of the setting. Likewise, most of the discourse acts employed are not only similar in both, but also have similar functions. The nature of the classrooms differ in the sense that the students in antenatal classroom are adults. Therefore, discourse acts such as bid, nomination, cue, clue, which are normally used in primary and secondary school classrooms did not feature prominently in antenatal classes. These discourse acts work in the context where the learners are younger and need some form of encouragement to participate in the discourse because of the difference in the age of teacher and learners. However, for most adult learners, who are already formed in terms of attitudes and behaviour, such discourse acts may not work. For such adult learners, whether to speak or not to speak is largely determined by their attitude to what is going on in the discourse, regardless of any form of prompting or encouragement from the teacher. Interestingly, however, chorus answer, which would normally be encouraged in classes with younger and less matured learners, is a feature of antenatal discourse in Nigeria. Since the instructors find it hard to get responses from the individual expectant mothers, they encourage chorus answers just to ensure that they are carrying along their students.

The findings have significant implications for health literacy programmes in Nigeria. It clearly shows that health literacy programmes, as we have observed in antenatal classrooms. exists only as an aspect of functional health literacy - the aspect that recognizes that pregnant women need to know about their health by listening to experts. This makes the practice as it is essentially transactional. The expectant women are not encouraged to move beyond this level of listening to such talks. Our findings show that the classes are not interactive enough. Therefore the women are in the position to use whatever they gain to influence the society.

The general picture presented by health specialists is that of the 'knower' (who only needs to pass across what is known) to the 'non-knower', (who needs to listen). The latter is not really in the position to critically evaluate and question what they are exposed to. They therefore remain passive learners, rather than active ones - mainly receiver of information.

For antenatal classrooms to achieve their goal of health security of pregnant women and their foetus, they have to be more interactive. There must be a departure from the lecture method used now to a method that actually involves the mothers. For instance, typical classes could start off with practical questions that would stimulate mothers to want to get involved in the discourse. With this, the involvement of the mothers will determine the direction of the discourse, and the nurses and midwives would only ensure that the discourse does not derail from the topic. The classes should also make use of more visual aids. These will aid the retention of what is learnt.

The antenatal classroom resembles the normal school classroom discourse, therefore most of the discourse acts used in the latter are used in antenatal classroom discourse. The predominant discourse acts in the antenatal classrooms studied were those, which placed the teacher in the position of transacting knowledge rather than interacting. However, interaction is the whole essence of communication. This places the pregnant women at the disadvantage of being passive learners, who cannot see the knowledge being passed across beyond the context of the class. Despite that they have access to information, they are not adequately empowered to influence the society with what they are being exposed to. The study suggests a more radical approach to antenatal education, and this is the approach which will be interactional, thereby more practical for the pregnant women.

Adegbite, Wale/Odebunmi, Akin (2006): "Discourse Tacts in Doctor-Patient Interactions in English. An Analysis of Diagnosis in Medical Communication in Nigeria". Nordic Journal of English Studies 15/4: 499-519.

Ainsworth-Vaughn, Nancy (1995): "Claiming Power in the medical Encounter. The Whirlpool Discourse". Qualitative Health Research 5/3: 270-291.

Ballinger, Claire/Ashburn, Anne/Low, Joe/Roderick, Paul (1999): "Unpacking the Blackbox of Therapy. A Pilot Study to Describe Occupational Therapy and Physiotherapy Interventions for People with stroke." Clinical Rehabilitation 13/4: 301-309.

Barnes, Douglas (1969): "Language in Secondary Classroom". In: Barnes, Douglas et al. (1969): Language, The Learner and The School. Hamondsworth: 9-77.

Campion, Peter/Langdon, Mark (2004): "Achieving Multiple Topic Shifts in Primary Care of Medical Consultations. A Conversational Analysis Study in UK General Practice". Sociology Health and Illnesses 26/1: 81-101.

Coulthard, Malcolm (1977): An Introduction to Discourse Analysis. London.

Coulthard, Malcolm/Ashby, Margaret C. (1976): "A Linguistic Description of Doctor-patient Interviews". In: Wadsworth, Michael/Robinson, David (eds.) (1976): Studies in Everyday Medical Life. London: 140-147.

Coupland, Justine/Robinson, Jeffrey D./Coupland, Nikolas (1994): "Frame Negotiation in Doctor-Elderly Patient Consultation". Discourse and Society 5/1: 89-124.

Crawford, Paul/Brown, Brian/Nolan, Peter (1998): Communicating Care. The Language of Nursing. Cheltenham.

Drew, Paul/Chatwin, John/Collins, Sarah (2001): "Conversational Analysis. A Method for Research into Interactions between Patients and Healthcare Professionals". Health Expectations 4/1: 58-70.

Flanders, Ned A. (1970): Analysing Teaching Behaviour. Bonn-Reading, Mass.

Gilkinson, A. (1991): "Antenatal Education. Whose purpose does it serve?" New Zealand College of Midwives Journal 1: 13-15.

Gulich, Elisabeth (2003): "Conversational Techniques Used in Transferring Knowledge between Medical Experts and Non-Experts". Discourse Studies 5/2: 235-263.

Heritage, John/Robinson, Jeffrey D. (2006): "The Structure of Patients' Presenting Concerns. Physicians' Opening Questions". Health Communication 19/2: 89-102.

Halliday, Michael A.K. (1961): "Categories of the Theory of Grammar". Word 17: 241-92.

Harison, Sandra (1996): "E-mail Discussions as Conversation: Moves and Acts in Sample From a Listserv Discussion. Linguistik Online 1, 1/98.

Labov, William/Fanshel, David (1977): Therapeutic Discourse. Psychotherapy as Conversation. New York.

Malouf, Robert (1995): Towards and Analysis of Multi-party Discourse. Available at http://odur.let.rug.nl/~malouf/papers/talk.pdf (accessed June 3, 2007).

Manning, Philip/Ray, George B. (2002): "Setting the Agenda. An Analysis of Negotiation Strategies in Clinical Talk". Health Communication 14/4: 451-473.

McCarthy, Michael (1991): Discourse Analysis for Language Teachers. Cambridge.

Nolan, Mary L. (1997): "Antenatal Education. Family to Educate for Parenthood". British Journal of Midwifery 5: 21-26.

Pilnick, Alison (1999): "'Patient Counselling' by Pharmacists. Advice, Information, or Instruction?" The Sociological Quarterly 40/4: 613-622.

Odebunmi, Akin (2005): "Cooperation in Doctor-Patient Conversational Interaction in South-Western Nigeria". In: Olateju, Moji A./Oyeleye (eds.) (2005): Perspectives on Language and Literature. Ile-Ife.

Odebunmi Akin (2006): "Locution in Medical Discourse in South-Western Nigeria". Pragmatics 16/1: 25-48.

Olateju, Moji A. (1997): Patterns of Interaction in the Science and Humanities ESL Classrooms. Ph. D. Thesis, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife.

Renkert, Susan/Nutbeam, Don (2001): "Opportunities to Improve Maternal Health Literacy through Antenatal Education. An Exploratory Study". Health Promotion International 16/4: 381-388.

Roberts, Gwerfyl W./Paden, Liz (2000): "Identifying the Factors Influencing Minority Language Use in Health Care Education Settings. A European Perspective". Journal of Advanced Nursing 32/1: 75-87.

Robinson, Jeffrey D. (2001) "Closing Medical Encounters. Two Physician Practices and their Implications for the Expression of Patients' Unstated Concerns". Social Science and Medicine 53/5: 639-656.

Sinclair, John McHardy/Coulthard, Malcolm (1975): Towards an Analysis of Discourse, the English Used by Teachers and Pupils. Oxford.

Sinclair, John McHardy/Coulthard, Malcolm (1992): "Towards an Analysis of Discourse". In: Coulthard, Malcolm (ed.) (1992): Advances in Spoke Discourse Analysis. London: 1-34.

Srenstrom, Anna-Britta (1994): An Introduction to Spoken Interaction. London.

Zobel, Emily (2002): An Updated Overview of Medical and Public Health Literature Addressing Literacy Issues. An Annotated Bibliography of Articles Published in 2001. Harvard. Available at http://www.hsph.harvard.edu/healthliteracy/literature/lit_2001.html (accessed June 3, 2007).

| 1 | Elicitation (elc) | This is realized by a question. Its function is to request a linguistic response. |

| 2 | Directive (dir) | This is realized by a command. Its function is to request a non-linguistic response. |

| 3 | Informative (inf) | This is realized by a statement. The function is to provide information. The only response is an acknowledgement of attention or understanding. |

| 4 | Prompt (prm) | This is realized by a closed class of items - 'go on', 'come on', 'hurry up', 'have a guess', etc. Its function is to reinforce a directive or elicitation by suggesting that the teacher is no longer requesting a response but expecting or demanding one. |

| 5 | Bid (bid) | This is realized by a closed class of verbal and non-verbal items - 'sir', 'miss', teachers name, raised hand, 'finger clicking', etc. Its function is to signal a desire to contribute to the discourse. |

| 6 | Re-state (res) | This is realized by statements that tend to repeat a point or an idea that had earlier on been mentioned. |

| 7 | Focus (foc) | This is realized by statements which are not strictly part of the discourse but inform us about what the topic is all about. |

| 8 | Frame (frm) | This is realized by words that indicate the boundaries in a lesson, such as 'right', 'today', 'good', 'well' etc. |

| 9 | Repetition (rpt) | This is realized by statements that are repeated to emphasize the importance of the message in the discourse. |

| 10 | Demonstration (dem) | This is realized by statements showing that the teacher is giving a practical illustration of what is being presented to the pupils. |

| 11 | Contrastive (con) | This is realized by a statement that are opposite of what had earlier been said. They are usually marked by expressions such as, in contrast to…', 'on the contrary' etc. |

| 12 | Illustrate (ill) | This is realized by a statement that adds to the information that had already been given. |

| 13 | Expatiate (exp) | This is realized by a statement that adds to the information that had already been given. |

| 14 | Additive (add) | This is realized by a statement, which gives additional information to the discourse. It is realized typically by words such as, 'and', 'in addition' etc. |

| 15 | Hearing/check (h/c) | This is realized by words such as 'hen', 'abi', (Yoruba expressions for 'is it so?') or any local language equivalent, which are meant to check whether the pupils are following the discourse. |

| 16 | Accept (acc) | This is realized by a closed class of items such as 'yes', 'no', 'good', 'fine', and a repetition of pupil's reply, all with neutral low-fall intonation. Its function is to indicate that the teacher has heard or seen and that the information, reply, or react was appropriate. |

| 17 | Comment (com) | This is realized by a statement or a tag question. It is subordinate to the head move. Its function is to expand, justify, and provide additional information. |

| 18 | Evaluation (eva) | This is realized by statements and tag questions including words and phrases such as 'good', 'fine', with high-fall intonation and repetition of pupil's reply with either a high-fall (positive evaluation) or a rise of any kind (negative evaluation). |

| 19 | Causative (cau) | This is realized by a statement showing that what is about to be said is as a result of one thing or the other. It is typically realized by words such as , 'so', 'therefore', 'as a result' etc. |

| 20 | Reply (rep) | This is realized by a statement, question or moodless item and non-verbal surrogates, such as nods. Its function is to provide a linguistic response, which appropriates elicitation. |

| 21 | React (rea) | This is realized by a non-linguistic action. Its function is to provide the appropriate non-linguistic response, which is appropriate to the directive. |

| 22 | Nominate (nom) | This is realized by a closed class consisting of names of all students. You, anybody, 'yes, etc.. The function is to give permission to a student to contribute to the discourse. |

| 001. | I: | Let us pray. (dir) Madam in blue blouse pray for us. (dir) | ||

| 002. | M: | Let us pray. (rea) God we thank you for being with us and for the position we are in right now. We pray that you will keep us in our pregnancy and you will help us to deliver safely in Jesus' name. (elc) | ||

| 003. | I: | Amen. (chorus answer) (rep) | ||

| 004. | M: | Now, (frm) Let us stand up. (foc) | ||

| 005. | M: | (reluctant to get up) (rea) | ||

| 006. | I: | Ha! You don't want to stand up to sing. You know we always sing whenever we come together like this. We will also sing today. (prm) Now, let us get up. (dir) | ||

| 007. | M: | (they stand up) (rea) | ||

| 008. | I: | We are going to sing about the appropriate diet we need to take in pregnancy. (inf)

| ||

| 009. | M: | (chorusing the song) (rep) | ||

| 010. | I: | Let us sit down. (dir) You are welcome to the clinic today. (inf) Today, (frm) we will be talking briefly about our hygiene and your posture in pregnancy. (foc) I can see that we are all very neat today. (inf) Can we clap for ourselves. (dir) | ||

| 011. | M: | (they sit down and clap) (rea) | ||

| 012. | I: | You are not clapping well. (prm) I want people at the other side of the road to hear our clapping. (dir) | ||

| 013. | M: | (clapping more vigorously and loudly) (rea) | ||

| 014. | I: | Thank you for clapping. (acc) Our discussion today is going to be very brief. (inf) For those who have been coming before, you will notice the diagrams on the wall. Can you see them? (elc) | ||

| 015. | M: | Yes. (chorus answer) (rep) | ||

| 016. | I: | You see, the diagrams on the wall tell us something. They are not there for fun. (inf) Look at those ones on your left. (dir) They show us how we ought to sit when we are pregnant. (inf) For instance, (uses a long stick to point at the diagram of a woman) the way this woman is sitting is not good and that is how most of you sit. (dem) Some women sit down while washing. That is very wrong. You should stand up while washing. Also, you should place your bucket on a small table. When you are having your bath, you should not bend down, or you will be endangering the life of the child. (inf) Now, let me ask you, when you want to get out of the bed, how do you do it? (elc) | ||

| 017. | M: | (no response) | ||

| 018. | I: | You mean nobody can tell me this? (prm) Okay, you should turn and then stand up. When you want to sweep the floor, please use long broom. (inf) Do you understand? (elc) | ||

| 019. | M: | Yes. (chorus answer) (rep) | ||

| 020. | I: | Also, when you want to pick anything on the floor, this is how you do it. (she

demonstrated by squatting to pick a piece of paper she dropped) (dem) Do you understand? (elc) | ||

| 021. | M: | Yes. (chorus answer) (rep) | ||

| 022. | I: | You should also sit on a chair with a strong back. (inf) | ||

| (a soya milk seller came around and the instructor calls her) | ||||

| 023. | SELLER: | Good morning ma. (elc) | ||

| 024. | I: | Good morning. (rep) Bring out your milk. (she raised up the soya milk in a nylon pack) (dir) You see, you need soya milk. (dem) It is part of a balanced diet. (inf) Do you understand? (elc) | ||

| 025. | M: | Yes. (chorus answer) | ||

| 026. | I: | If we don't take good and balanced diet, it will affect our children adversely. We should eat plenty of fish, meat, beans, and oil. It is better to eat good food than to take drugs. We should always be neat. Remember, whatever you are is what your baby is. (inf) When a woman gives birth to a child, who does the child first see? (elc) | ||

| 027. | M: | The mother. (chorus answer) (rep) | ||

| 028. | I: | The mother, (res) Thank you. (acc) You as a mother determines the hygiene of your baby. A neat baby is a healthy baby. (inf) Now tell me, If your baby is neat, won't people want to carry it? (elc) | ||

| 029. | M: | They will. (chorus answer) (rep) | ||

| 030. | I: | Who has a question. (elc) | ||

| 031. | M: | (a mother raised up her hand) (rep) | ||

| 032. | I: | Yes, our mummy. (nom) | ||

| 033. | M: | How many wrappers are we expected to bring along to the hospital for delivery? (elc) We often hear that sometimes bed sheets are not available. (inf) | ||

| 034. | I: | Two. (chorus answer) (rep) | ||

| 035. | M: | Thank you for the question. (eva) At least, you should have four wrappers. If you come to the hospital and bed sheets are not available, you can use one as your bed sheet. You will use another one to wrap your baby. (inf) How may will remain? (elc) | ||

| 036. | I: | You can also use one for yourself. Then, keep the remaining one. (inf) Any other question? (elc) | ||

| 037. | M: | (no answer) | ||

| 038. | I: | You had better ask your questions now. (prm) (pauses to see if anybody will signify) Okay, if we have no question or contribution, we will stop here for now. Another colleague of mine will come and talk to about other things. (inf) I pray that the Lord will grant all of you safe delivery. (elc) | ||

| 039. | M: | Amen. (chorus answer) (rep) | ||

| 040. | I: | Matron, please come and address our mother. (dir) | ||

| (matron walks to the front of the mothers)... | ||||