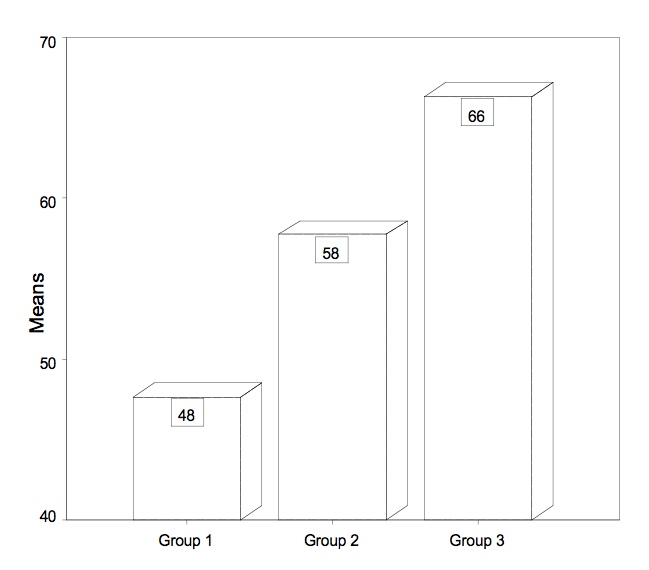

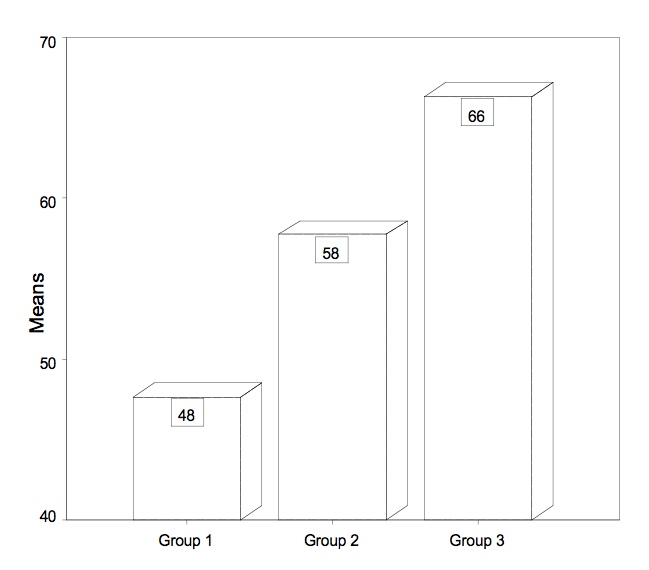

Figure 1: The OPT Results for the Juniors

In recent years, an emerging theme in SLA has been the degree to which L2 learners acquire the capacity to express themselves in the TL using culturally appropriate figurative language (Danesi 1994). While this ability to generate metaphors in the TL might not appear to be essential to self-expression on the face of it, it is becoming ever more palpable that the more we fathom about language, thought, and cognition, the more we find ourselves challenged with the weighty task of trying to define, explain, and understand metaphors.

Most attempts in Second Language Teaching (SLT) have been directed towards the enhancement of linguistic and communicative competences. We have almost been successful in training L2 learners to have a good command of grammar and communication; however, there is something still not quite kosher in the actual L2-learner discourse - something that goes beyond grammatical and communicative proficiency, i.e., something that cannot be explained in precisely grammatical and/or communicative terms (Danesi 1992). While L2-learner discourse might show a high degree of verbal fluency, it invariably seems to lack the conceptual appropriateness that typifies that of natives. That is L2 learners speak or write with the formal structures of the TL but think in terms of their L1 conceptual system: L2 learners usually apply TL words and structures as carriers of their own L1 concepts. When these accord with the ways in which concepts are structured in the TL, then the L2-learner texts coincide serendipitously with culturally appropriate texts; when they do not, their texts manifest an asymmetry between language form and conceptual content. What L2-learner discourse typically lacks is conceptual fluency (CF). Danesi (1992) claims that metaphorical competence (MC) is as crucial as the linguistic and communicative competences since it is tightly linked to the ways in which a culture organizes its world conceptually. Not only thinking and acting are based on this conceptual system, but in large part communication as well. The programming of discourse in metaphorical ways is an integral trait of native-speaker competence.

Since the mid-1980s, the practice has been to use metaphor to refer to the study of all figurative language and to consider the other tropes as particular kinds of metaphor (Danesi 2003). Verbal fluency is defined as the grammatical and communicative abilities of an L2 learner: The ability to produce grammatically and communicatively appropriate discourse in an L2. Conceptual fluency is the ability to use and comprehend the conceptual concepts of a given language. To be conceptually fluent in a language is to know how that language reflects or encodes its concepts on the basis of metaphorical structuring. Metaphorical competence is the ability to comprehend and use metaphors in a given language as used in natural discourse. Metaphorical density refers to the total number of metaphors divided by the total number of sentences multiplied by 100. A metaphorical sentence is a token or instantiation of the underlying culturally appropriate conceptual system. Any sentence comprising a metaphorical or figurative language (e.g. metaphor, idiom, and simile) is taken as a metaphorical sentence.

Although SLA researchers (e.g. Cook 1993; Ellis 1986, 1994; Gass/Selinker 1994) tell us a great deal about how L2 learners acquire an L2, they are as good as silent on the subject of metaphor and idiom, unlike their teacher-training colleagues, who are full of good ideas (e.g. Danesi 1992; Lindstromberg 1991; Low 1988). Why should such an obviously ubiquitous dimension of language use be almost ignored by our field? Is it because grammatical theories have traditionally regarded metaphor as cumbersome, and we are hung up on grammatical theory? Or, is it because metaphor is seen primarily as a literary device, so of peripheral interest to most L2 learners? Whatever the reason, if metaphorical language is as prevalent in everyday language as the frequency counts suggest, then presumably mastery of the forms and functions of the conventional repertoire constitutes an important part of what it means to know a language. And by extension, the successful acquisition of an L2 will entail the development of a new repertoire of metaphorical language (Danesi 1992, 2003).

The lack of awareness of metaphorical concepts and lexical strategies often lead L2 learners to render a metaphorical expression in the L2 by using an analogous counterpart of their L1. So, the meaning of a word or sentence is frequently translated literally by activating the L1 concept owing to a lack of knowledge of all possible meanings a word or expression could have: The concept from the L1 is simply translated into the L2 or vice versa. Since "metaphor is the main mechanism through which we comprehend abstract concepts and perform abstract reasoning" (Lakoff 1993), teaching should make L2 learners aware of the L2 conceptual system. Also, L2 learners should be encouraged to make use of metaphorical language, "to produce and comprehend metaphors as tools of communication and thought" (Stight 1979).

Mastery of appropriate use of metaphorical expressions in an L2 has been acknowledged as one of the greatest challenges facing L2 learners. Empirical investigations of L2 figurative language use have been guided mainly by pedagogical concerns about the appropriate use of humor (Deneire 1995; Schmitz 2002), irony, sarcasm, idioms (Cooper 1999), metaphor (Danesi 1992), and other forms of figurative expressions in an L2 context. Despite the research done on CF and MC, little research has been done, to the best of my knowledge, to see if Persian students majoring in English in Iran develop CF and MC in English after several years of study. The present study was an attempt to address the preceding issue: Whether or not Persian students majoring in English develop CF and MC in the TL after several years of studying English. The study examined to what extent they understood and produced metaphors in English, and it analyzed the Metaphorical Density (MD) of their written discourse. It also sifted whether CF and MC could be developed in a classroom setting. Moreover, the study investigated to see whether there was any relationship between CF and MC.

For most people, metaphor is a device of the poetic imagination and the rhetorical flourish, a matter of extraordinary rather than ordinary language; it is by and large taken as typical of language alone, a matter of words rather than thought or action; and most people assume they can get along well without metaphor. But, metaphor is pervasive in everyday life, not just in language but also in thought and action. Contrary to the position often expressed in mainstream linguistics, metaphor is not at the margins of language; rather, as Harris (1981) convincingly argues, it 'is at the very heart of everyday mental and linguistics activity' (cited in Lantolf 1999: 42). Lakoff and Johnson (1980) define metaphor as a process by which we conceive "one thing in terms of another, and its primary function is understanding." Metaphors provide a means for understanding something abstract in terms of something concrete. They are not just "poetic" but rather determine "usage" in our language: These metaphors inform normal ways of talking about life situations. Our ordinary conceptual system, in terms of which we both think and act, is basically metaphorical in nature (Lakoff/Johnson 1980).

But this conceptual system is not something we are normally aware of. In most of the little things we perform every day, we simply think and act more or less automatically along certain lines. What these lines are is by no means well-defined. One way to find out is by looking at language. Since communication is based on the same conceptual system that we use in thinking and acting, language is a significant source of evidence for what that system is like. Primarily in line with linguistic evidence, Lakoff and Johnson (1980) assert that most of our ordinary conceptual system is metaphorical in nature. They hold that metaphor is not just a matter of language, i. e., of mere words; rather, human thought processes are largely metaphorical. Metaphors as linguistic expressions are possible precisely because there are metaphors in a person's conceptual system (Lakoff/Johnson 1980). The conceptual system is a model of reality upon which is based every aspect of human symbolic behavior. Our social organizations, religious beliefs, figurative arts, and language are rooted in it in some essential way. Analysis of any one of these aspects of human behavior would shed some light onto the structure of the conceptual system. However, the analysis of language is particularly illuminating since language is our primary means of communication.

The study of metaphor and its relation to language and cognition took on a new direction in the 1980's with the publication of Lakoff and Johnson's Metaphors We Live By (1980) and with the further development of their ideas later in the decade (Lakoff 1987; Johnson 1987). Their basic contention is that metaphors are not merely an embellishment of language, a rhetorical device, or a poetic reference, but rather metaphors and the capacity to metaphorize are a fundamental aspect of human cognition. According to their theory, human perception and behavior is governed by and mediated through a non-linguistic conceptual system which is fundamental in how we organize and understand our percepts, thoughts, and consequently, reality. Since the relationship between the concepts in the conceptual system is metaphorical, metaphor at the conceptual level becomes "understanding and experiencing one kind of thing in terms of another" (Lakoff/Johnson 1980). In essence, this is the heart of what they call experimentalism: The philosophy that the nature and the structure of reality is in a very fundamental way connected to our ability to perceive, understand, and act.

Metaphors are used permanently in everyday communication, politics, education, science, etc. Most universal and basic concepts of the world we live in, e.g., time, state, and quantity, are understood via metaphorical mappings. They stem from our concrete daily experience and our knowledge of the world and are projected onto abstract concepts, thus acting as a pattern for the formation of such. For instance, the conceptual metaphor MORE IS UP mirrors a mapping process, in which quantity is associated with vertical movement such as prices are high or I'm feeling up.Most of our cognitive processes, the way we think, act, perceive, and view the world, are based on metaphorical concepts that structure and influence our language: "Our conceptual system, thus, plays a central role in defining our everyday realities" (Lakoff/Johnson 1980).

Gibbs (1994), in surveying the psycholinguistic literature on figurative language, shows that in appropriate contexts people more often process the metaphorical properties of a message than they do so its so-called literal meaning. Metaphors are, therefore, an equally, if not more important, feature of communicative interaction (cited in Lantolf/Thorne 2006: 113). Beck (1982) saw that the conceptual system described by Lakoff and Johnson has potential applications in education, especially in language study and in cultural understanding. Recently, Danesi (1986, 1989, 1992, 1994, 1995, 2003) has applied this view of language and thought to the field of SLT and SLA. He contends that in order to fully learn a language, we must also have the ability to access and encode our expressions according to the conceptual system in which the language is rooted. This neglected dimension in L2 pedagogy is what Danesi (1992) calls MC: When L2 learners have attained a native-like MC, it may be said they are conceptually fluent. He contends that to date, teaching practice has not imparted this ability to L2 learners. Conceptual Fluency Theory holds that underlying any given linguistic system is a conceptual system which serves as the basis not only for language, but also for cognitive functioning in general: We speak, think, perceive, and interpret the world in terms of our conceptual system. In acquiring another language, therefore, L2 learners must express themselves in the TL while utilizing the L2 conceptual system in order to express themselves in a truly native-like fashion. To be conceptually fluent is to be able to partake in a target culture perception of the physical and social world and to interact with it like a native.

Lantolf (1999) proposed that learning an L2 from the perspective of culture entails much more than complying with the behavioral (linguistics or otherwise) patterns of a host culture. He argues that it is about the appropriation of cultural models, including conceptual metaphors, and therefore entails the use of meaning as a way of (re)mediating our psychological and, by implication, our communicative activity. Kecskes and Papp (2000) argue that if learners acquire grammatical and communicative knowledge but fail to develop conceptual knowledge in a new language, their knowledge use will be significantly different from that of native users. Boers (2000: 564), on the other hand, proposes a less ambitious goal in arguing for the need for learners to develop "metaphor awareness" as opposed to the ability to generate metaphors in the L2, so that they will at least be able to "organize the steady stream of figurative language they are exposed to." Likewise, Littlemore (2002: 484) suggests that "the ability to interpret metaphors quickly in conversation can be a crucial element of interaction."

Figurative language competence has aroused the interest of a number of L2 researchers. Leading the front are Danesi (1992, 1995) and Johnson and Rosano (1993), who state that metaphors and idioms should not be ignored by L2 curricula any longer. Their push is to instill in L2 learners a more functional communicative competence over a traditional formal competence. Danesi (1995) argues that L2 learners do not reach the fluency level of a native speaker until they have knowledge of "how that language 'reflects' or 'encodes' concepts on the basis of metaphorical reasoning" (p. 5). Other L2 researchers interested in CF have investigated formulaic expressions (Kecskes 2000; Wray 2003), phrasal verbs (Matlock/Heredia 2002) and idioms (Bortfeld 2002; Cooper 1999).

First, 139 juniors majoring in English partook in the study and were assigned to three groups. Before the study, their MC was assessed by a teacher-made test, comprising metaphors, idioms, and the like. Then, 187 other participants, as a comparison group, were tested for their MC: 95 freshmen, 92 sophomores, and 90 seniors. Finally, 23 native speakers of English were asked to write a paragraph each, and the MD of their writings was examined.

Specifically designed to tap into all the participants' MC, the pretest comprised two sections: One on the comprehension and the other on the production of metaphorical language. The posttest was designed to appraise the juniors' CF and MC, in terms of comprehension and production of metaphors as well as comprehension of a handful of L2 conceptual metaphors. And the Oxford Placement Test (OPT) was used to assign the juniors to the three groups above.

One of the books selected for instruction was Idioms Organiser (1999), the rationale for choosing which was to expose the juniors to some L2 conceptual metaphors, out of which were born some 206 metaphors and idioms. The other book was 136 American English Idioms (2004), which exposed them to 136 idioms. Also, 10 imaginative stories were retrieved from the Internet, each of which focused on certain metaphors and idioms, for instance, politics and hand-related terms, breeding some 210 metaphors and idioms. Moreover, some quizzes on idiomatic language, producing some 295 idioms and expressions, were given to them during the program.

The main participants were 139 juniors enrolled in a course, meeting for 90 minutes, once a week, for 16 consecutive weeks. First, they were tested via the OPT and assigned to the afore-mentioned groups. Then, they were given a pretest to check their MC. As for the MD of their written discourse, they were required to write their first paragraph before the launching of the study. And they were instructed to write their second paragraph after the study was wrapped up.

As for the instruction of metaphorical language, they were initially given some idea of what conceptual metaphors are, and how it is possible to generate innumerable metaphors and idioms out of such conceptual metaphors. To give some idea of what it could mean for a concept to be metaphorical and for such a concept to structure an everyday activity, this researcher exemplified with the concept ARGUMENT and the conceptual metaphor ARGUMENT IS WAR. This metaphor is reflected in English by a wide variety of expressions:

| Your claims are indefensible. |

| He attacked every weak point in my argument. |

| His criticisms were right on target. |

| I demolished his argument. |

| I've never won an argument with him. |

| If you use that strategy, he'll wipe you out. |

| He shot down all of my arguments. |

The juniors were reminded that we do not just talk about arguments in terms of wars. We can actually win or lose arguments. We see the person we are arguing with as an opponent. We attack his position and we defend our own. We gain and lose ground. We plan and use strategies. If we find a position indefensible, we can abandon it and take a new line of attack. Many of the things we do in arguing are partially structured by the concept of war. Though there is no physical battle, there is a verbal battle, and the structure of an argument reflects this. It is in this sense that the ARGUMENT IS WAR metaphor is one that we live by in English: It structures the actions we perform in arguing. It is not that arguments are a subspecies of wars. Arguments and wars are different kinds of things - verbal discourse and armed conflict - and the actions performed are different kinds of actions. But arguments are partially structured, understood, performed, and talked about in terms of wars. The concept, the activity, and language are metaphorically structured. Moreover, this is the ordinary way of having an argument and talking about one.

As for Idioms Organiser, each unit opens with a conceptual metaphor such as THE OFFICE IS A BATTLEFIELD. Initially, the juniors were instructed that there are two concepts here: One is an abstract concept office, and another is a concrete one battlefield. Next, the literal meanings of the words coming from the concrete concept were examined in various sentences. Regarding the domain of battlefield, there are words like to stab, to command,and sight. When it comes to taking about office, the same words could be used metaphorically: To stab sb in the back, one's second in command, and to set one's sights.After examining the literal meanings of the words from concrete domains, they were to study the various metaphors and idioms generated from such domains. They were to look up the meaning of the metaphorical language if needed, fill in the exercises with such language, write their own metaphorical sentences and apply them in communicative activities in the classroom, and finally write one paragraph for each unit, encouraged to use the metaphors and idioms in their writings.

Regarding 136 American English Idioms, the juniors were to learn 10 idioms for each session. Each idiom is put in an authentic context, along with its definition and an illustration to help L2 learners grasp the meaning of each idiom. They were to write their own metaphorical sentences and were encouraged to involve in communicative activities in the classroom, harnessing the assimilated metaphors and idioms.

As to the stories, each student had a copy of a story for each session. Each text had the story with the metaphors and idioms in bold, followed by blank spaces. The students were to read each story, look up the meaning of the metaphorical language, fill in the gaps provided for the literal meanings of the metaphors, and come to the class loaded for bear. Then, one of them read the story aloud and clarified the meaning of the idiomatic language. There were times in which the meanings were challenging, and this researcher provided the necessary help. Also, a number of quizzes were given to them from time to time, most of which were in the form of fill-in-the blank exercises. They were to do the exercises, find the meanings of the expressions and idioms, and come to the classroom prepared. In the classroom, the exercises were done individually, and the potentially problematic meaning areas were eradicated.

The 187 other participants (95 freshmen, 92 sophomores and 90 seniors) were also tested for their MC. They were compared to the juniors in order to see whether MC develops after 4 years of study. Also, they were all required to write a paragraph each in order to assess the MD of their written discourse. Moreover, in order to have a criterion for the MD of native-speaker written discourse, 23 native speakers were asked to write a paragraph each, and the MD of their writings was calculated.

As shown in Figure 1, the juniors were assigned to three groups: Group 1 consisted of 48 juniors with a mean of 47.64; Group 2 included 43 juniors with a mean of 57.74; and Group 3 encompassed 48 juniors with a mean of 66.31:

Figure 1: The OPT Results for the Juniors

In order to see the probable effect of the treatment, the scores from the pretest and posttest were statistically analyzed. The results in Table 1 all show there is a significant difference between the means of the two performances of the above groups:

| Groups | Pre-Test vs. Post-Test Sections | T | df | Sig. (2-tailed) | |||

| Mean | Std. Deviation | Std. Error of Mean | |||||

| 1 | Comprehension Production Total Scores |

67.18 20.22 87.54 |

10.20 10.26 18.19 |

1.47 1.48 2.62 |

45.6 13.6 33.3 |

47 47 47 |

.000 .000 .000 |

| 2 | Comprehension Production Total Scores |

73.11 28.20 101.58 |

10.05 10.67 19.35 |

1.53 1.62 2.95 |

47.6 17.3 34.4 |

42 42 42 |

.000 .000 .000 |

| 3 | Comprehension Production Total Scores |

76.08 31.85 107.93 |

11.52 9.97 20.19 |

1.66 1.44 2.91 |

45.73 22.1 37.0 |

47 47 47 |

.000 .000 .000 |

Table 1: Matched T-Test for the Juniors

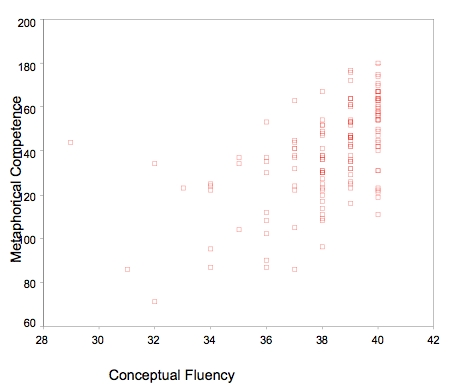

In order to see whether there was any relation between CF and MC, the scores from the third section of the posttest (Conceptual Fluency Section) were compared with the total scores of the Comprehension and Production Sections and statistically analyzed. Table 2 and Figure 2 show that there is a moderate relationship between CF and MC:

| Groups | Conceptual Fluency | Metaphorical Competence | ||

| 1 | Conceptual Fluency | Pearson Correlation Sig. (2-tailed) N |

1.000 48 |

.524** .000 48 |

| Metaphorical Competence | Pearson Correlation Sig. (2-tailed) N |

.542** .000 48 |

1.000 48 |

|

| 2 | Conceptual Fluency | Pearson Correlation Sig. (2-tailed) N |

1.000 43 |

.374** .013 43 |

| Metaphorical Competence | Pearson Correlation Sig. (2-tailed) N |

.374** .013 43 |

1.000 43 |

|

| 3 | Conceptual Fluency | Pearson Correlation Sig. (2-tailed) N |

1.000 48 |

.621** .000 48 |

| Metaphorical Competence | Pearson Correlation Sig. (2-tailed) N |

.621** .000 48 |

1.000 48 |

|

Table 2: Correlation between CF & MC

Figure 2: Scatter Plot for CF & MC for All the Juniors

In order to see whether L2 learners at various levels develop MC, the scores from the test given to the freshmen, sophomores, juniors, and seniors were compared and subjected to statistical operations. Since there seemed to be a difference in mean scores of the participants, the data was further subjected to statistical analysis and the analysis showed there was a difference among the four groups (F = 96.45, df = 3, α = 0.05, p = 0.00). In order to see which of the above groups was different, the data was subjected to post hoc analysis, and Table 3 (see the Appendix) and Table 4 below show that the Freshmen Group was different:

| Groups | Subset for α=.05 | |||

| 1 | 2 | |||

| Tukey | Freshmen Sophomores Juniors Seniors Sig. |

95 92 139 90 |

27.70 1.000 |

39.51 40.23 40.30 .803 |

| Duncan | Freshmen Sophomores Juniors Seniors Sig. |

95 92 139 90 |

27.70 1.000 |

39.51 40.23 40.30 .399 |

Table 4: Homogeneous Groups

Before discussing the MD of the written discourse in this study, it should be mentioned that in order to guarantee maximum inter-rater reliability, each paragraph was examined by three independent raters for its MD, and the average metaphorical density (AMD) of each paragraph was finally calculated.

In order to examine the MD of all the participants' written discourse, they were asked to write a paragraph each. Then, the AMD of their written discourse was statistically compared, and the data indicated that there was a difference among the four groups (F = 11.12, df = 3, α = 0.05, p = 0.00). In order to see which of the groups was different, the data was subjected to post hoc analysis, and Table 5 (see the Appendix) and Table 6 below show that the Seniors Group was different:

| Groups | Subset for α=.05 | |||

| 1 | 2 | |||

| Tukey | Freshmen Sophomores Juniors Seniors Sig. |

95 92 139 90 |

6.61 7.97 8.00 .769 |

.1472555 1.000 |

| Duncan | Freshmen Sophomores Juniors Seniors Sig. |

95 92 139 90 |

27.70 1.000 |

39.51 40.23 40.30 .399 |

Table 6: Homogeneous Groups

In order to see whether the MD of the seniors' writings had approached that of the natives, the AMD of their written discourse was compared with that of the natives. Table 7 (see the Appendix) shows there was a significant difference between the two groups.

As mentioned before, the juniors were asked to write two paragraphs: One before the study and one after the study. In order to see if there was any significant difference between the MD of their two writings, the results were subjected to statistical analysis, and Table 8 shows there was a significant difference between the means of their two writings:

| Groups | The Juniors' Writings | Paired Differences | T | df | Sig. (2-tailed) | ||

| Mean | Std. Deviation | Std. Error of Mean | |||||

| 1 | AMD (Before & After the Study) | -.4079 | .10639 | 1.5 | -26.56 | 47 | .000 |

| 2 | AMD (Before & After the Study) | -.4046 | 9.30 | 1.4 | -28.52 | 42 | .000 |

| 3 | AMD (Before & After the Study) | -.4220 | .10669 | 1.5 | -27.40 | 47 | .000 |

Table 8: AMD of the Written Discourse by he Juniors

Moreover, in order to make sure whether the MD of the juniors' second writings had approached that of the natives, the AMD of their second writing was compared with that of the natives. Table 9 (see the Appendix) shows that there was not a significant difference between the two groups.

Recent research has found that L2 learners of high grammatical proficiency will not necessarily show concomitant pragmatic skills. Some scholars explained non-native-like production by the lack of CF and MC in the TL (Kecskes 1999; Danesi 1992, 2003). Previous research on CF (Danesi 1992, 1993; Russo 1997) suggests that L2 learners show virtually no traces of CF after many years of study. The results of this are indicative that L2 learners do not develop CF and MC after several years of study. The findings also suggest that MC, even at the level of comprehension, is inadequate in L2 learners. The reason for this is not that they are incompetent to learn the conceptual system of L2, but rather they have never been exposed to the conceptual system of the TL in formal or systematic ways. To be conceptually fluent in the TL, the student must be able to convert common experiences into conceptually and linguistically appropriate models. At this stage of the game, Danesi (2003) claims there seems to be very little in L2 methodology which takes CF and MC into account in any orderly fashion.

However, the findings here indicate that it is possible to enhance L2 learners' CF and MC in a classroom setting. By systematically taking L2 conceptual concepts and their metaphorical realizations into account and incorporating them in L2 textbooks and methodology, this researcher believes it is possible to boost this crucial aspect of L2 proficiency in L2 learners. The juniors did not know almost anything about metaphorical language before launching the study, but they did develop their CF and MC after the study was wrapped up. Not only did they produce and understand discourse that was conceptually and metaphorically appropriate in English, they also produced writings which were as metaphorically dense as those of native speakers. So, the data backs up Danesi's (1992) claim that MC is the neglected dimension in SLA and SLT. It also implies it is feasible for us practitioners to systematically incorporate metaphors in L2 syllabus, and in this way to make L2 learners aware of the conceptual system of the TL and to encourage them to apply metaphorical language in their everyday language use.

As for the MD of the L2 learners' written discourse, what could be gleaned from the data here is that vis-ˆ-vis native speakers, the L2 learners had little or no access to the conceptual system of English. That was why their written discourse showed a high degree of literalness. All the participants (freshmen, sophomores, juniors, and seniors) were asked to write a paragraph at the beginning of the study, and the analysis of their compositions showed almost no sign of the conceptual system of English. That is, the L2 learners knew almost nothing about thinking conceptually and writing metaphorically after four years of studying English. This finding corroborates Danesi's (1992) argument that L2 learners learn almost no new way of thinking conceptually after several years of study in a classroom.

Specifically, the juniors were asked to write two pieces of writing: One before the study and another after the study. The data vividly revealed that the MD of their second written discourse was much higher than that of their first one. This finding once more probably reinforces the idea that it is possible to boost L2 learners' CF and MC in a classroom setting. The reason why their second discourse was much more metaphorically dense than their first one could be attributed to the fact that their CF and MC in English had developed. Their second writings were also compared with those of the native speakers, and the results made plain that they could produce written discourse which was as metaphorically dense as that of the native speakers. Once again, the data probably substantiates the notion that it is possible to build up L2 learners' CF and MC via systematic ways and in an orderly fashion.

Research suggests that at least a certain portion of the human mind is programmed to think metaphorically (Lakoff/Johnson 1980; Lakoff 1987; Johnson 1987; Danesi 1992). Metaphor probably underlies the representation of a considerable part of our common concepts. According to Danesi (1992), MC is a basic feature of native-speaker discourse because native speakers usually program discourse in metaphorical ways. At this point, however, Valeva's criticism (1996) of Danesi's approach appears to be correct. She argued against the reduction of CF to MC. There are many literal concepts, in the sense of being directly understood, without any metaphorical processes. This is true: MC is a very important part of CF, but it would be a mistake to equate MC with CF (Kecskes 1999). The findings here bear out Valeva's (1996) claim. CF and MC are related, but the relationship is not a causal one. It could be said there is a moderate relationship between CF and MC at the outside. Consequently, the heart of the problem is: To what extent can CF and MC be developed in an L2 setting? Danesi (1992) suggest that MC is inadequate in typical classroom learners, and that L2 learners' writings show a high degree of literalness. His conclusion is that, after three or four years of study, L2 learners learn almost no new way of thinking conceptually, but rely mainly on their L1 conceptual base.

The importance of developing CF has been emphasized in other contexts in a number of research reports. Irujo (1993) suggested that students should be taught strategies to deal with figurative language, and those strategies would help them take advantage of the semantic transparency of some idioms. Kövecses and Szabó (1996) argued that teaching about orientational metaphors underlying phrasal verbs will result in a better acquisition of this difficult type of idiom. Bouton (1994) reported that formal instruction designed to develop pragmatic skills seemed to be highly effective when it was focused on formulaic implicatures. These studies suggest that CF (including MC) can be developed in the classroom if students are taught about the underlying cognitive mechanisms. Valeva (1996), however, thinks that the issue of learnability should be investigated before facing the question of teachability, and it is still an open question whether the conceptual system of an L2 is learnable or not in a classroom setting (Kecskes, 1999). The findings here imply that CF and MC could be developed in a classroom setting. The juniors initially knew almost nothing about conceptual metaphors and their metaphorical realizations in English, but they did have a good command of the English conceptual metaphors and metaphorical expressions after the study was ended. That is why they performed much better on the posttest and their second writing task. Therefore, it could be held that the conceptual system of an L2 is learnable if it is treated in an orderly and systematic fashion. To be precise, it is conceivable to expose L2 learners to the conceptual concepts of the L2, teach them about these concepts, expose them to the TL metaphorical language, and sensitize them to such concepts and such language during the process of L2 learning. The awareness of metaphorical expressions in an L2 can create an even deeper empathy, sympathy, and interest for the L2 culture. Of course, this does not imply a radical change in instruction; rather, it entails a refocusing of traditional practices and techniques.

As language teachers, we try many methods to help our students enhance their passive and active lexical knowledge. One of the most efficient ways, in my view, for L2 learners to assimilate new words and expressions is through the study of metaphorical language. Indeed, the Oxford Dictionary of English Idioms (1993) states in its introduction that the "accurate and appropriate use of English expressions which are in the broadest sense idiomatic is one distinguishing mark of a native command of the language and a reliable measure of the proficiency of foreign learners" (p. x). Once L2 learners are able not only to understand metaphorical expressions but also to produce them, we can say they have reached a high level of L2 proficiency. The results of this study are indicative that it is likely in L2 classes to focus on metaphorical language in order to help L2 learners achieve an acceptable level of proficiency in an L2 so far as MC is concerned.

Danesi (1992) has claimed that metaphor is the neglected dimension in SLT and SLAR. The findings here imply that it could be imaginable for metaphornot to be the neglected area in SLT and SLAR any longer. It is all plain sailing to integrate metaphorical language in L2 syllabus and methodology, and we might witness the day that L2 learners would develop not only their linguistic and communicative competences but also their metaphorical competence. Danesi (1992) asserts that MC must be extracted from the continuum of discourse and held up for L2 learners to study and practice in ways that are analogous to how we teach them grammar and communication. The data here corroborates his assertion, given that MC was treated autonomously in this study. The juniors were exposed only to the conceptual system and metaphorical expressions of English during the program, and that was probably why they became somehow conceptually fluent and metaphorically competent at the end of the study. In a nutshell, the data makes evident that L2 learners do not develop CF and MC by osmosis in view of the fact that they are also exposed to authentic materials during their BA program, which are supposedly imbued with metaphorically structured discourse.

As Danesi (1986, 1992, 1994, 1995, 2003) has repeatedly put it forward, the implications of metaphor and MC for SLT and SLA should be meticulously examined. A very specific implication that the notions of MC and CF hold for SLAR and L2 methodology is that these notions are in no way mutually exclusive of grammatical and communicative competences. As Danesi (1992) maintains, it is very probable that all the three competences constitute overlapping layers in discourse programming. We now know quite a lot about how the grammatical and communicative layers operate; the time has come to look at how and where the metaphorical layer fits in.

Another implication is to ask if metaphor is cognitively more salient and versatile than literal, propositional discourse. Research on so-called anomalous strings (e.g., Colorless green ideas sleep furiously), for example, has shown that the metaphorizing capacity forces people to extract meaning from almost any well-formed combination of words (e.g., Pollio/Burns 1977; Pollio/Smith 1979). If people are required to interpret such strings, then they will do so, no matter how contrived the interpretation might appear. This suggests that metaphorical thinking is a dominant and ever-present option in discourse, and that literal thinking might actually constitute a special, limited case of communicative behavior. In the absence of contextual information for an utterance such as "The murderer is an animal," we are immediately inclined to apply the metaphorical mode in interpretation. It is only when we are told that the so-called "murder" was committed by a biological animal that a literal interpretation becomes possible. This is probably due to the fact that literal speech is tied to the verbalization of the infinite universe of ACTUAL WORLDS, whereas metaphor extends discourse into the infinite universe of POTENTIAL WORLDS (Danesi 1992).

Still another implication is that it is feasible for L2 learners to boost the MD of their discourse provided that they build on their CF and MC in the TL. The juniors' first written discourse manifested a very low MD, but their second one exhibited a high MD. The data revealed that their second written discourse was almost as metaphorically dense as that of native speakers, too. Thus, it could be argued that L2 learners have the potential to approach native speakers as far as the MD of their written discourse is concerned. It is just a matter of teaching L2 learners explicitly about the conceptual system of the TL and its metaphorical expressions and of encouraging them to harness their MC in their written and/or spoken discourse.

And, the concluding implication of this study might be that metaphor instruction presented here could be incorporated into EFL programs for L2 learners at all levels of English proficiency. Metaphor instruction features direct teaching of metaphorical language through the use of conceptual metaphors as cognitive tools for language learning. It may be adopted equally and easily by Persian-speaking teachers as the instructional method for dealing with L2 learners' difficulties in learning metaphorical expressions. Metaphor instruction here employed the use of "pictures" as instructional aids in design. A picture that depicts the concrete term in a conceptual metaphor provides the common ground on which the teachers and the learners can communicate ideas effectively since the pictorial representation of the vehicle term minimizes potential semantic problems. With the presence of pictures assisting metaphor instruction procedures, literal descriptions are depicted and metaphorical expressions are concretized. It is not necessary for the learners to mark the meanings of the TL in L1. The use of pictures adds meaning comprehension to the instructional language and promotes communication and discussion between the teacher and the learners. Pictures can assist the use of conceptual metaphors in EFL learning in the way that they can draw L2 learners' attention and perception, hold their interest continuously, and engage them in applying known experience or knowledge in the process of understanding abstract information. The use of pictures reinforces the imagery function of conceptual metaphors.

The conclusions drawn from this study are limited due to certain shortcomings inherent in a study of this nature. Therefore, the findings cannot be taken as definitive answers to the questions of this research. It is the present researcher's hope that the results of this mostly empirically-based study serve as a step in a better understanding of CF and MC in L2, and in coming closer to a better understanding of L2 proficiency.

* The authors wish to thank the Office of Graduate Studies of the University of Isfahan for their support! back

Beck, Brenda (1982): "Root metaphor patterns". Semiotic Inquiry 2: 86-97.

Boers, Frank (2000): "Metaphor awareness and vocabulary retention". Applied Linguistics 21: 553-571.

Bortfeld, Heather (2002): "What native and non-native speakers' images for idioms tell us about figurative language". In: Heredia, Roberto R./Altarriba, Jeanette (eds.) (2002): Advances in psychology. Bilingual sentence processing. Amsterdam: 275-295.

Bouton, Lawrence F. (1994): "Can NNS skill in interpreting implicatures in American English be improved through explicit instruction? A Pilot Study". In: Bouton, Lawrence F./ Kacher J. (eds.) (1994): Pragmatics and Language Learning. Urbana-Champaign: 88-110.

Cook, Vivian J. (1993): Linguistics and second language acquisition. Britain.

Cooper, Thomas C. (1999): "Processing of idioms by L2 learners of English". TESOL Quarterly 33, (2): 233-262.

Danesi, Marcel (1986): "The role of metaphor in second language pedagogy". Rassegna Italiana di Linguistica Applicata 18, (3): 1-10.

Danesi, Marcel (1989): "The role of metaphor in cognition". Semiotica 77: 521-31.

Danesi, Marcel (1992): "Metaphorical competence in second language acquisition and second language teaching: The neglected dimension". In: Alatis, James E. (ed.) (1992): Georgetown university round table on languages and linguistics. Washington.

Danesi, Marcel (1993): Vico, metaphor, and the origin of language. Bloomington.

Danesi, Marcel (1994): "Recent research on metaphor and teaching of Italian". Italica 71: 453-464.

Danesi, Marcel (1995): "Learning and teaching languages: The role of conceptual fluency". International Journal of Applied Linguistics 5, (1): 3-20.

Danesi, Marcel (2003): Second language teaching. A view from the right side of the brain. Dordrecht.

Deneire, Marc (1995): "Humor and foreign language teaching". Humor 8, (3): 285-298.

Ellis, Rod (1986): Understanding second language acquisition. Oxford.

Ellis, Rod (1994): The study of second language acquisition. Oxford.

Gass, Susan M./Selinker, Larry (1994): Second language acquisition. An introductory course. New Jersey.

Gibbs, Raymond. W. Jr. (1994): The poetics of mind. Figurative thought, language and understanding. Cambridge.

Grice, Paul H. (1975): "Logic and conversation". In: Cole, Peter/Morgan, Jerry L. (eds.): Speech acts. Syntax and semantics. New York: 41-58.

Harris, Roy (1981): The language myth. London: Duckworth.

Irujo, Suzanne (1993): "Steering clear. Avoidance in the production of idioms". IRAL 31, (3): 205-219.

Johnson, Mark H. (1987): The body in the mind. The bodily basis of meaning, reason and imagination. Chicago.

Johnson, Janice/Rosano, Teresa (1993): "Relation of cognitive style to metaphor interpretation and second language proficiency". Applied Psycholinguistics 14, (21): 59-175.

Kecskes, Istvan (2000): "Conceptual fluency and the use of situation-bound utterances in L2". Links & Letters 7: 145-161. Available at http://ddd.uab.es/pub/lal/11337397n7p145.pdf.

Kecskes, Istvan (2000): "A cognitive-pragmatic approach to situation-bound utterances". Journal of Pragmatics 32: 605-625.

Kecskes, Istvan/Papp, Tünde (2000): Foreign language and mother tongue. Mahweh, N. J.

Kövecses, Zoltán/Szabó, Péter (1996): "Idioms. A view from cognitive semantics". Applied Linguistics 17, (3): 326-355.

Lakoff, George (1987): Women, fire, and dangerous things. Chicago.

Lakoff, George (1993): "The contemporary theory of metaphor". In: A. Ortony (ed.): Metaphor and thought (2nd ed.). Cambridge: 202-251.

Lakoff, George/Johnson, Mark L. (1980): Metaphors we live by. Chicago.

Lantolf, James P. (1999): "Second culture acquisition. Cognitive consideration". In: Eli Hinkel (ed.): Culture in second language teaching and learning. Cambridge.

Lantolf, James. P./Thorne, Steven. L. (2006): Sociocultural theory and the genesis of second language development. Oxford.

Lindstromberg, Seth (1991): "Metaphor and ESP. A ghost in the machine?" English for Specific Purposes 10: 207-225.

Littlemore, Jeannette. (2001): "Metaphoric competence. A possible language learning strength of students with a holistic cognitive style". TESOL Quarterly 34, (3): 459-91.

Low, Graham D. (1988): "On teaching metaphor". Applied Linguistics 9, (2): 125-147.

Matlock, Teenie/Heredia, Roberto R., (2002): "Lexical access of phrasal verbs and verb-prepositions by monolinguals and bilinguals". In Roberto R. Heredia, & Jeanette Altarriba (eds.): Advances in psychology. Bilingual sentence processing. Amsterdam: 251-274.

Pollio, Howard R./Burns, Barbara C. (1977): "The anomaly of anomaly". Journal of Psycholinguistic Research 6: 247-260.

Pollio, Howard./Smith, Michael K. (1979): "Sense and nonsense in thinking about anomaly and metaphor". Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society 13: 323-326.

Russo, Gerard A. (1997): A Conceptual Fluency Framework for the Teaching of Italian as a Second Language. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Toronto.

Schmitz, John Robert (2002): "Humor as a pedagogical tool in foreign language and translation courses". Humor: International Journal of Humor Research 15, (1): 89-113.

Searle, John R. (1979): Expression and meaning. Cambridge.

Sticht, Thomas. G. (1979): "Educational uses of metaphor". In: Andrew Ortony (ed.): Metaphor and thought (2nd ed.). Cambridge: 474-485.

Valeva, Gloria (1996): "On the notion of conceptual fluency in a second language". In: Pavlenko, Aneta/Salaberry, Rafael S. (eds.): Cornell working papers in linguistics. Papers in second language acquisition and bilingualism. Ithaca: 22-38.

Winner, Ellen (1982): Invented worlds. The psychology of the arts. Cambridge, MA.

Wray, Alison (2003): Formulaic language and the lexicon. Cambridge.

| (I) Group | (J) Group | Mean Difference (I-J) | Std. Error | Sig. | |

| Tukey HSD | Freshmen | Sophomores Juniors Seniors |

-11.80* -12.52* -12.59* |

.96 .75 .97 |

.000 .000 .000 |

| Sophomores | Freshmen Juniors Seniors |

11.80 -.71 -.78 |

.96 .75 .97 |

.000 .778 .851 |

|

| Juniors | Freshmen Sophomores Seniors |

12.52* .71 -6.978 |

.75 .75 .76 |

.000 .778 1.000 |

|

| Seniors | Freshmen Sophomores Juniors |

12.59* .78 6.978 |

.97 .97 .76 |

.000 .851 1.000 |

|

| LSD | Freshmen | Sophomores Juniors Seniors |

-11.80* -12.52* -12.59* |

.96 .75 .97 |

.000 .000 .000 |

| Sophomores | Juniors Freshmen Seniors |

11.80* -.71 -.78 |

.96 .75 .97 |

.000 .344 .420 |

|

| Juniors | Freshmen Sophomores Seniors |

12.52* .71 -6.978 |

.75 .75 .76 |

.000 .344 .927 |

|

| Seniors | Freshmen Sophomores Juniors |

12.59* .78 6.978 |

.97 .97 .76 |

.000 .420 .927 |

Table 3: Multiple Comparisons of All the Participants

| (I) Group | (J) Group | Mean Difference (I-J) | Std. Error | Sig. | |

| Tukey HSD | Freshmen | Sophomores Juniors Seniors |

-1.3635 -1.3858 -8.1144* |

1.597 1.244 1.604 |

.827 .681 .000 |

| Sophomores | Freshmen Juniors Seniors |

1.3635 -2.2307 -6.7509* |

1.591 1.244 1.604 |

.827 1.000 .000 |

|

| Juniors | Freshmen Sophomores Seniors |

1.3858 2.2307 -6.7286* |

1.244 1.244 1.261 |

.681 1.000 .000 |

|

| Seniors | Freshmen Sophomores Juniors |

8.1144* 6.7509* 6.7286* |

1.604 1.604 1.261 |

.000 .000 .000 |

|

| LSD | Freshmen | Sophomores Juniors Seniors |

-1.3635 -1.3858 -8.1144* |

1.591 1.244 1.604 |

.392 .267 .000 |

| Sophomores | Juniors Freshmen Seniors |

1.3635 -2.2307 -6.7509* |

1.591 1.244 1.604 |

.392 .986 .000 |

|

| Juniors | Freshmen Sophomores Seniors |

1.3858 2.2307 -6.7286* |

1.244 1.244 1.261 |

.267 .986 .000 |

|

| Seniors | Freshmen Sophomores Juniors |

8.1144* 6.7509* 6.7286* |

1.604 1.604 1.261 |

.000 .000 .000 |

Table 5: Multiple Comparisons of All the Participants

| F | Sig. | T | df | Sig. (2-tailed) | Mean Difference | Std. Error Difference | |

| Equal Variances Assumed | 34.465 | .000 | -4.25 | 111 | .000 | -33.13 | 5.44 |

| Equal Variances Not Assumed | .550 | 29.30 | .585 | 1.31 | 2.39 | ||

Table 7: Independent-Samples T-Test

| F | Sig. | T | df | Sig. (2-tailed) | Mean Difference | Std. Error Difference | |

| Equal Variances Assumed | .307 | .580 | .561 | 160 | .575 | 1.31 | 2.34 |

| Equal Variances Not Assumed | .550 | 29.30 | .585 | 1.31 | 2.39 | ||

Table 9. Independent-Samples T-Test