Appropriate reference to other sources is an important feature of academic writing. In writing scholarly papers, researcher writers do not want only to show their own credibility in research. But they also need to refer to other works, their findings, and their results. They make references to the works of others in order to frame and support their own work and also to establish a niche for themselves within their special discourse community. An important aspect is to learn how to cite other works in an appropriate style. To understand the importance of citation in the academic setting it would be enough to say that citation, if used properly, would be against literacy piracy.

Academic writers not only need to make the results of their research public and persuasive, they should also show that their success in gaining acceptance for their work is at least partly dependent on the strategic manipulation of various rhetorical and interactive features (White 2004: 341). White also regards citation as a complex communicative purpose with syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic variables (cf. White 2004: 112) which is of interest not only to EAP scholars (e. g., Charles 2006; Hyland 1999; Petric 2007; Swales 1986, 1990; Thompson 2001, 2005) but also information scientists (White 2004). In discourse analysis, citations have often been examined in terms of reporting verbs (Hyland 1999; Thompson/Ye 1991) which enable the writer to position their work in relation to the works of other research. Despite the differences in approaches and methods, researchers agree that the role of citation in scientific discourse is not only to acknowledge the works of others but also to promote the writer's own knowledge claims.

Hyland (1999) believes that one of the most important realizations of the research writer's concern for audience is that of attributing propositional content to the existing literature and demonstrating accommodation to the community knowledge. As a core tool in the research discipline, citations are crucial in any research to situate the work and to build on the works of others (Wohlin 2008). Because citation involves creating intertextual relationships between the citing and the cited texts, it is especially prone to occlusion. Indeed, occlusion is implicit in the existence of conventions for citation. The conventional signals for source reporting are, therefore, needed to allow the writer to reveal as much of the relationship as she or he thinks the reader needs to know (cf. Pecorari 2006: 6).

Thompson (2005) investigated the nature of genre and citation practices in eight Ph.D. theses within Agricultural Botany at a British university. He identified citation types and observed their relation to content, writer, and rhetorical purposes. In studying social science − Politics − and natural science − Materials − theses, Charles (2006a, b) found that reporting clauses were considerably more frequent in social sciences than in natural sciences. Other differences aside, both social and natural sciences made use of research sources roughly equally. This confirmed that reporting clauses were often associated with citation and they often occur as integral citations. In sum, the data revealed disciplinary differences in the frequency and the stance function of the clauses. Comparison of the two corpora showed that human subjects occurred more often in Politics while non-human and it subjects were more frequent in Materials. Thus, the writers created a stance that was appropriate to their discipline and purpose.

Petric (2007) aimed to identify the relationship between the types of citation and high- and low-rated master's theses. The corpus used in that study consisted of 16 master's theses (eight A-graded theses and eight lower-graded theses), written by second language writers from 12 countries in Central and Eastern Europe. She used Thompson's (2001) classification of citation types (attribution or source, origin, reference, and example) with some modifications to classify both integral and non-integral citations. A total of 1981 citations were identified in 310'624 words, of which 1253 were in the high-rated theses (182'896 words) and 729 in the low-rated ones (127'728 words), alluding to greater citation density in high-rated theses with more syntactic and rhetorical complexities.

By taking the importance of citation role into account, the present study investigates intertextuality in terms of citations utilized in MA theses. Writers are seeking to position themselves in relation to members of the research community, as they perceive them, and this is most evident in the introduction section. How they position themselves varies from writer to writer. In the context of Iran, the investigation of the way that Iranian thesis writers cite in their introduction sections and position themselves within the discourse community has been overlooked although there have been a few works identifying citation in different sections of articles (Jalilifar 2010; Shooshtari/Jalilifar 2010).

Thesis writing is a difficult process for native speaker students and often doubly so for non-native speaker students (Paltridge 2002: 137). Some researchers consider MA theses as one of the key genres used by scientific communities to disseminate knowledge (Koutsantoni 2006: 20); others consider MA theses as a high stakes genre at the summit of a student's academic accomplishment (Hyland 2004a: 134). Samraj and Monk (2008: 194) acknowledge the abundance of works on published academic texts such as research articles, but they regret that in terms on graduate students' writing, to which MA theses belong, little work has been done. The ability to cite appropriately is of key importance in academic writing (Charles 2006b: 311), but it produces considerable difficulties for the novice writer. The investigation of citation patterns has particular value, since it can reveal the way that different writers express themselves, which can be linked to genre and/or disciplinary purposes. Paying attention to citation in academic writing courses would encourage students to examine the different types of citations, and also it will help them to become aware of the functions of citation within the text.

Introduction is considered as a specific and crucial "part-genre" (Dudley-Evans 1997: 5) to set out their research questions, in both research articles and MA theses (Hyland 2002: 542). Citation features of MA thesis introductions (MAIs) have even been a less charted territory area of consideration than research article introductions. According to Paltridge (2002: 126), one reason can be the accessibility of the text, that is "Theses and dissertations are often difficult to obtain in university libraries, and even more difficult to obtain from outside the university". In Iran, as a foreign language learning context, all English-major students are required to write their MA theses in English; such students (non-native), according to Samuelowicz (1987, as cited in Paltridge: 2002: 127) often have difficulty in meeting the demands of the kind of writing required of them at this particular level. Therefore, writing an MA thesis is perhaps the most significant piece of writing that any student will ever do (Hyland 2004a: 134). In MA theses, the supervisor and the reader may ignore citations because they know that in the defense session, apart from some general assumptions about citation and plagiarism, judgments may not depend so much on the ways students cite and the types of citations MA students use in their writing. This is a lethargic performance which may make students less attentive to this important textual feature of academic writing. Hence, MA students rarely are criticized for their citation behavior. By focusing on the nature of citation patterns in one of the "citation-dense chapters" (Pecorari 2003: 322), we can help students to write more successful MA theses.

Accordingly, the question that is posed in this study is: In what way are citations exploited in the introductions of Iranian MA English theses in applied linguistics?

Sixty five MAIs were selected on an available basis from the Iranian universities − Tehran University (UT), Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz (SCU), and Science and Research Branch-Ahvaz (SRA). The corpus was assumed to comprise and represent samples of high-rated MA theses associated with these universities. Since generic structures and rhetorical structures are subject to variation across time, we selected those which were published between 2005 and 2009. In carrying out the study, one vexed problem was accessing MA theses from universities, which led to the unequal selection of MA theses from each university. The trend in Iran is that the Research Department of the faculties does not usually allow students to copy theses or borrow from the Research library. They are only allowed to use them on site. This constraint took us an extensive amount of time to sit and take notes. The theses were codified for ease of reference and anonymity of thesis writers (e. g., UTI 1 referred to an introduction from Tehran University).

|

SCU |

SRA |

UT |

|

16 |

28 |

21 |

Table 1: Number of Theses from each University

In this study, Thompson and Tribble's (2001) framework for integral and non-integral citations was used as the instrument to analyze and compare the materials. The main categories which Thompson and Tribbles (2001) set are as follows: a) integral citation consisting of three sub classes; b) non-integral citation consisting of four sub-categories. Thompson and Tribble's (2001) classification assumed to be comprehensive and it takes accounts of all the citations types. According to Thompson and Tribbles (2001: 95), non-integral citations are divided into four categories:

a) Source or attribution: Source indicates where the idea or information is taken from, as in this example:

1. Learning style is the biologically and developmentally imposed set of characteristics that make the same teaching wonderful for some and terrible for others (Brown 2000). (UT)

b) Identification: This citation type identifies an agent within the sentence it refers to. An example of this type is:

2. In fact, a great deal of work has been done in the area of learner autonomy... (Haughton/Dickinson 1988; Cotterall 1995; Murray 1999; Chan 2001, 2003; Spratt Humphreys/Chan 2002; Clegg 2004; White 2006). (UT)

c) Reference: This is usually signaled by the inclusion of the directive "see", as in:

3. acquisition is insufficient for L2 learners… (See Cobb/Meara 1998: 2). (SCU)

d) Origin: This indicates the originator of a concept, technique or product, as shown in the following example:

4. … discourse markers, which are also known by a variety of names, such as pragmatic markers (Schiffrin 1987), discourse particles or discourse operators (Schourup 1999), and discourse connectives (Blackmore 2002). (SRA)

Thompson and Tribble (2001: 95f.) classify integral citation can be as follows:

a) Verb controlling: The citation acts as the agent that controls a verb, in active or passive voice, as in:

5. Brown and Yule (1983: 183) point out that theme is not only the starting point of the message, but it also has a role in connecting what has already been said. (SRA)

b) Naming: In this kind of citation, the citation is a noun phrase or part of a noun phrase. An example of this type is:

6. According to Oxford (1994), a second language is a language studied in a setting where… (UT)

c) Non-citation: There is a reference to another writer but the name is given without a year reference. It is most commonly used when the reference has been supplied earlier in the text and the writer does not want to repeat it, as in:

7. Hyland states that citation represents choices that carry ….(SRA)

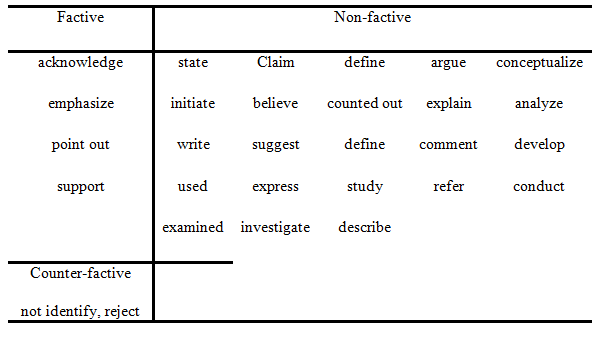

To identify stance in the verb controlling type of integral citation, Thompson and Ye's (1991) framework was used. According to this classification, one of the most important ways of evaluation in reporting verbs is identified through writer's stance. Based on this taxonomy, reporting verbs which writers use can be categorized into three sub-categories as follows: a) factive in which the writer portrays the author as presenting true information or a correct opinion, for example, acknowledge, bring out, demonstrate, identify, improve, notice, prove, recognize, substantiate, throw light on; b) counter-factive in which the writer portrays the author as presenting false information or an incorrect opinion, for example, betray (ignorance), confuse, disregard, ignore, misuse; and c) non-factive in which the writer gives no clear signal as to her attitude towards the author's information or opinion, for example, advance, believe, claim, examine, generalize, propose, retain, urge, utilize (Thompson/Ye, 1991:. 372). This framework has been extensively applied by researchers on different sections in different disciplines (e. g., Hyland 1999). See Appendix A for the verbs identified in verb controlling citations.

Once the corpora were compiled, citations were identified following Hyland's (2000) criteria. Each occurrence of another author's name was counted as one citation, regardless of whether it was followed by the year of publication or not. The analysis did not include textual elements outside of the main text, such as epigraphs and explanatory footnotes. After the selection of the text corpus, word count was run on in order to determine the length of the corpus. Then the data were stored according to Thompson and Tribble (2001) to identify and classify each type of citation. Finally, the frequency of integral and non-integral citations was calculated to detect the possible differences in the citation classes and judge whether the differences are significant.

The framework used in the study is functional, allowing us to look at the contextual nature of citations. Thus, our study provides analyses at both quantitative and qualitative levels.

The first step taken in the analysis of citation types in the introduction sections of MA theses was to run word count to determine the length of the corpus. A total of 1'134 citations were identified in 79'886 words, in the MA theses.

|

Av. per work Per 1000 words Total citations |

|

MA theses 17.44 14.19 1134 |

Table 2: Citations in M.A Theses

Table 2 indicates the importance of citations in academic writing, with an average of almost 17.44 in thesis introductions, depicting the characterization that MA theses tend to employ citations.

Surface Forms of Citations in MA Theses

Different citation types are used to substantiate claims in thesis introductions. Table 3 demonstrates the variation in the ways Iranian MA students refer to sources, with a distinct preference for integral citation. As the results showed, the use of integral citations was more than one and a half that of non-integral citations.

|

Integral |

Non-integral |

X2 |

Df |

Sig |

|

|

Theses |

699 |

435 |

61.46 |

1 |

.00 |

| P < 0.05 | Critical value = 3.84 |

Table 3: Citation Types in Thesis Introductions

To find out whether the existing differences between integral and non-integral citations were significant, chi-square test was applied. The value of chi-square (61.46) was higher than the critical value (3.84) at the significant level of P < 0.05. This showed a significant difference in the frequency of citation types in thesis introductions. Accordingly, the use of integral citations was considered more than one and a half that of non-integral citations. That is to say, writers tended to use integral citations far more than non-integral.

Integral Citations in MA Theses

Within integral citations (Table 4), greater emphasis was given to Verb controlling by Iranian MA students.

|

Theses |

|||

|

F |

(%) |

||

|

Verb controlling |

453 |

(64.80) |

|

|

Integral |

Naming |

189 |

(27.04) |

|

Non-citation |

57 |

(8.16) |

|

|

Total |

699 |

||

Table 4: Types of Integral Citation in Thesis Introductions

As shown in Table 4, Verb controlling was the most frequent citation within integral citations of theses. Following Thompson and Ye's (1991) classification of reporting verbs, the verbs were classified based on the fact that writers (the writer of the actual text) may represent the reported text of an author (the one who is cited by the writer) as a) true using factive verbs; b) false using counter-factive verbs; and c) non-factively, given no clear signal. Findings showed that MA theses tend to use factive verbs to represent the cited text as true in the Verb controlling citation frequently, as in:

8. Swain and Lapkin (1995: 372) point out to the result of a … (SRA)

Several sentences in theses were found in which the writer draws on factive verbs in order to represent the cited text as true (e. g. acknowledge, point out, establish, etc). Non-factive verbs received the highest frequency in theses by which writers represent neutral stance toward the cited text and withhold judgment, as in:

9. Celce-Murcia (2001: 3) believes that one reason… (SCU)

Counter-factive categories in which the cited text was represented as false were found only three times in MA theses, as in:

10. Knight (1994), however, has rejected this view... (SCU)

In the above sentence, the writer shows the author's disagreement using the verb "rejected". Further examples of counter-factive verbs are fail, overlook, exaggerate, ignore, etc, which were not found in this study. (see Appendixes B for stance in integral citations).

In the present study as shown in Table 4, the Naming type occurs second in rank of the most frequent citations used in MA introduction sections. Close inspection of the different kinds of Naming citation in the theses revealed interesting findings in the discourse of this genre. Bear in mind that citation in Naming is within the sentence but it does not control the verb. In order to find out why this might be the case, concordance lines of the Naming citation were drawn. It was observed that certain patterns were regularly used, as those depicted in Table 5.

|

Naming citation patterns |

Theses |

|

|

f (%) |

||

|

according to X (2005)… |

97 |

51.32 |

|

X' (2005) study/theory |

24 |

12.69 |

|

…that/work of X (2005) |

17 |

8.9 |

|

…in X (2005) / |

7 |

3.70 |

|

…to X (2005) x is… |

5 |

2.64 |

|

…for X (2005) x is… |

5 |

2.64 |

|

…by X (2005) |

10 |

5.29 |

|

based on X (2005) |

9 |

4.76 |

|

following X (2005)… |

5 |

2.64 |

|

in accordance/line with X(2005) |

2 |

1.05 |

|

taken /adapted from X (2005) |

8 |

4.23 |

|

Total |

189 |

|

Table 5: Naming Citation Patterns in Theses

The pattern "according to X" is clearly the preferred choice in the MA theses. In this pattern, the writer focuses on author who does not receive the agent position. The pattern which received the second highest frequency in the MA theses was the "X's study". MA students tend to use those noun phrases which function as modifier. Notice the following example:

11. Oxford's (1998) study of students…

The use of "in X" pattern in MA theses was (f = 7), which is contradicts Thompson's (2001) study in which he found "in X" pattern the most common Naming citation pattern used in Agricultural Botany theses. This type of citation refers to the "work" of an especial author, but the word "work" is not mentioned explicitly. Here is an example of this pattern:

12. It is not mentioned in Jordan (1997), even though this standard …(SCU)

Other examples of preposition + Naming citation were found to be "by X (2005)" pattern, which was not frequent in MA theses, as in:

13. ...the large scale cross-sectional study by MacIntyre et al. (2002) which… (SRA)

In this pattern, the overall focus is on the work of a particular researcher. Other patterns of Naming citation were rare in the data, and examples of Non-citation were still far less than Verb controlling and Naming in MA theses and (f = 57).

Non-integral Citation in MA Theses

Table 6 shows that non-integral citation was mostly realized by writers in the form of Source in thesis introductions, as a strategy to attribute information to an author.

|

Theses |

||

|

Non-integral |

F |

(%) |

|

Source |

369 |

(84.82) |

|

Identification |

42 |

(9.65) |

|

Reference |

8 |

(1.83) |

|

Origin |

16 |

(3.67) |

|

Total |

435 |

|

Table 6: Distribution of non-integral citations

Reference , used to persuade readers to see other texts, was found to appear less than other non-integral citation in MA theses (F = 8), as exemplified below:

14. ..acquisition is insufficient for L2 learners…(See Cobb/Meara 1998: 2). (SCU)

Origin , which can function as an indication of the origin of a theory, technique or product, was also found inconspicuous in MA theses, as in:

15. …discourse markers, which are also known by a variety of names, such as pragmatic markers (Schiffrin, 1987), discourse particles or discourse operators (Schourup, 1999), and discourse connectives (Blackmore, 2002). (SRA)

In this example, the writer attributed the "known names for discourse markers", to several originators. Here, the difference between Origin andSource seems to be tricky but, according to Thompson and Tribble's (2001: 95) definition, "where Source attributes a proposition to a source, Origin indicates the originator of a concept or a product". Iranian MA students exploited the latter type of non-integral citations infrequently (about 3.67% of non-integral citations). Instead, they prefer to denote the cited concept and proposition to an author (Source) rather than to introduce the creator of that concept (Origin). In Thompson's (2005) study of theses, where he identified citations in different rhetorical sections, writers were more concerned with Origin citation in the method sections; however, in introduction sections of theses, no Origin was identified; accordingly, he considered it as "typical features of method sections" (Thompson 2005: 316), since in the method section the materials and methods are described for the analyses.

In view of the question which asks for the distribution of citations employed by MA students in the introduction sections of their applied linguistics theses, analysis showed significant differences in the citation practices. Integral citations tended to give greater prominence to the cited sources in MA theses. Results showed a pronounced tendency to use integral citations in which the name of the researcher appears as a sentence element with an explicit grammatical role.

Charles (2006b) believes that the choice of integral/ non-integral citation is a complex product of a number of factors including citation convention, genre, discipline and individual study type (cf. Charles 2006b: 317). In this study, however, the preference for integral citation does not seem to be only related to the citation conventions, but to the functions of citations in theses, in which writers prefer to emphasize the author especially in subject position (by using verb controlling citation). This complies with the communicative purposes pursued by MA students, since they tend to establish a strong support for their claims within the text by placing the citation within the sentence and emphasizing the researcher rather than the information.

Citation practices reflect students' social and epistemological conventions, their audiences, and citation conventions. MA students are not likely to show a high share of knowledge in applying different citation types according to the standards established by their target discourse community. They do not set a discursive framework of integral and non-integral citations in order to establish a space for their research and for their possible publication. In order to publish their work, a paper should meet certain characteristics, and these characteristics should be acceptable to the editors of the journals. It seems that MA students do not stick to those principles set by journals gatekeepers, which may arise from their unawareness of conventions of citation practices; as such their work may get little space for publication if they wish to publish it in condensed form.

In academic writing, especially in MA theses, students tend to choose appropriate information supporting their study, without offering any subjective interpretation by means of verbs (e. g. factive and counter-factive verbs). In fact, they do not evaluate the reported text, but they only tend to report it, often using appropriate grammatical patterns, that is, whether to place the author in the subject position in integral citation, or to enclose it parenthetically while they may ignore the rhetorical and discourse level of citation. Thompson and Ye (1991) argue that to concentrate only on the given information would in many cases be to miss or misinterpret the purpose. They add that "evaluation in text is the signaling of this purpose" (Thompson/Ye 1991: 367).

MA students tend to report previous research (hence more integral citations) rather than evaluate it, and they point it out for the purpose of creating a research space for their study in the introduction, simply by summarizing it and integrating it into their study. Taylor and Chen (1991, as cited in Fakhri 2004) also reported that the absence of evaluation of previous research can be attributed to the unacceptability of argumentative styles and self-promotion in the cultures considered. The descriptive rather than argumentative nature of MA thesis introductions may stem from the lack of competitive publishing environment and avoidance of self-promotion in the Iranian culture. The authors of the local studies are familiar with the academic practices in their respective culture and the socio-cultural stigmatization of direct confrontation and self-promotion. So lack of critical evaluation may be related to cross-cultural variation. Fakhri (2004) reports that communicative styles in different cultures vary in terms of directness, that is, the degree to which speakers and writers reveal their intentions. Western cultures prefer direct, explicit communication styles whereas the Japanese, Iranian, and Arab cultures value indirectness (cf. Fakhri 2004: 1131).

Moreover, Iranian students are likely to have fewer resources at their disposal when they come to cite the works of others because they are less skilled writers of academic discourse. Verb controlling citations are in some ways the easiest and most obvious ways of incorporating citations into text. However, professionals, especially if they are native-speakers, possess a wider range of linguistic options to draw which could fit in with the findings of the present study that the Iranian writers used more integral citation.

Of the citation types sporadically utilized in this study, one was reference used by writers as a "shorthand device" (Thompson 2001: 105) to direct the reader to another text in which exact details can be found. Writers should decide whether it is necessary to provide details or to use the word see and make the reader responsible for reading and understanding more details about the subject. For Hyland (2002), these devices (e. g. see ) belong to "directives" which show somewhat the writer's ability for gathering information from sources as well as his ability to direct the reader. Reference, if used properly, can be one of the "conventional signals" which, as Pecorari (2006) claims, are needed for source reporting to allow the writer to reveal as much of the relationship as she or he thinks the reader needs to know.

The way that citations are manifested in MA theses may reflect the context in which citations are used by these writers. One determining element of this context is audience. MA students write mostly for Iranian readers with different attitudes and expectations. They may receive no critical feedback from their readers. Thus, they may not be aware of the rhetorical effect of citations as international writers do. MA students' preference for only two types of integral citation may be indicative of their less proficient knowledge citation.

Another reason is the size of the community they address. Iranian MA students address a small discourse community in comparison to international writers who address a much greater discourse community with quite different expectations and language knowledge. Looking at the results of the present study, one may claim that MA students make use of a distinct pattern of the citation types (namely integral citation) and they seem to have little knowledge. MA students are not at the appropriate stage of linguistic or intellectual development, and so they apply limited citation practices (Charles 2006b; Hyland 1999; Petric 2007; Thompson/Tribble 2001). This works against the inclination of expert writers for non-integral citations in published articles (Jogthong 2001; Okamura 2008), and/or their equal tendency toward these two types of citation. MA students focus on the explicit grammatical roles of citations and do not give an equal weight to the reported author and the message. The existing rhetorical patterns in the citation practices in the MA thesis introductions mark the underlying social structures accepted by novice writers in applied linguistics. As argued by Martin (2000: 9), "the stage a culture has reached in its evolution provides the social context for the linguistic development…" and this linguistic development "provides resources for the instantiation of unfolding texts". Therefore, citation as an important feature in academic writing brings to surface those social structure differences that exist and determine the way writers' intentions are shaped. This becomes more revealing to us in relation to MA theses that are not shaped by experienced academic writers.

The findings of the present study have pointed to the existence of various citations across this academic writing type. The study revealed significant differences between MA students' tendencies to use integral and non-integral types of citation with the greater tendency to use the former. Findings also give a broad view of MA students' tendencies in the use of citation subtypes and that MA students define citation in different ways and consider that their readers cannot be assumed to possess the same interpretive knowledge. The breadth of citation reflects the complexity of citation practices, and this in turn makes it difficult for novice writers in learning to cite appropriately. In general, the findings therefore suggest that citation use should receive more attention in EAP courses. The study identified both the common rhetorical and linguistic features reflected in theses, which in turn, reflect the social and cultural contexts, as well as writers' aim of writing. The preference for a special type of citation within MA theses (i. e. integral) shows their familiarity with formal features of citation, for instance to use an author in a subject position and give explicit grammatical role to the author but their ignorance of the functional features of citation. We should bear in mind that citation practice is like a two sided coin, with formal and grammatical features constituting only one side. This might stem in unfamiliarity of Iranian MA students with the functional aspects of citation that each simple citation conveys because, in fact, they do not usually receive explicit instructions on citation practices.

In addition, Iranian students' less use of non-integral citation shows that they usually emphasize the authors in their writing rather than the information, leading us to conclude that supervisors may not criticize MA students' for their citation patterns or they may not pay due attention to the way their students cite in theses; instead, they focus upon linguistic and grammatical features of theses and ignore functional characteristics.

The way that we have looked at citation in the context of MA thesis writing has got its own newness. Moreover, the problems encountered by Iranian MA thesis writers might not necessarily be experienced by MA students representing other nationalities. This requires further studies before one can make generalizations about citations in this genre.

Investigating usual citation patterns used in theses, textbooks or articles will enhance students' understanding of what lies behind the citation choices. Accurate use of citation can be considered as one important way to prevent plagiarism, so, EAP teachers can provide a wide range of citation functions and different forms to teach novice writers. A particularly interesting direction for future research would be a cross-disciplinary comparison of citation patterns used by Iranian students and other researchers. This will allows us to see the disciplinary differences in citing authors in academic writing.

At the time of publication of this paper, Alireza Jalilifar is affiliated with the Shahid Chamran University of Ahvaz, Iran, and Razieh Dabbi is affiliated with the Islamic Azad University in Mahshahr, Iran.

Charles, Maggie (2006a): "The construction of stance in reporting clauses: A cross disciplinary study of theses". Applied Linguistics 27/3: 492–518.

Charles, Maggie (2006b): "Phraseological patterns in reporting clauses used in citation: A corpus-based study of theses in two disciplines". English for Specific Purposes 25: 310–331.

Dudley-Evans, Tony (1997): "Genre models for the teaching of academic writing to second language speakers: Advantages and disadvantages".In: Miller, Tom E. (1997): Functional approaches to written text: classroom applications. Washington, DC, USA: 150–159.

Fakhri, Ahmed (2004): "Rhetorical properties of Arabic research article introductions". Journal of Pragmatics 36: 1119–1138.

Hyland, Ken (1999). "Academic attribution: Citation and the construction of disciplinary knowledge". Applied Linguistics 20/3: 341–367.

Hyland, Ken (2000): Disciplinary discourses: Social interactions in academic writing. Harlow: Longman.

Hyland, Ken (2001): "Bringing in the reader: Addressee features in academic writing". Written Communication 18/4: 549–574.

Hyland, Ken (2002): "Directives: Argument and engagement in academic writing". Applied linguistics 23/2: 215–239.

Hyland, Ken (2004a): "Disciplinary interactions: Metadiscourse in L2 postgraduate writing". Journal of Second Language Writing 13: 133–151.

Hyland, Ken (2004b): "Patterns of engagement: Dialogic features and L2 understanding writing". In: Ravellie, Louise/ Ellis, Rod. (eds.) (2004): Analyzing academic writing. England, Continuum: 6–23.

Jalilifar, Alireza (2010): "Research article introductions: Subdisciplinary variations in applied linguistics". Journal of Teaching Language Skills 2/2: 29–55.

Jogthong, Chalermsri (2001): Research article introductions in Thai: Genre analysis of academic writing. Unpublished doctoral thesis, Morgantown, West Virginia, Department of Educational Theory and Practice.

Koutsantoni, Dimitra (2006): "Rhetorical strategies in engineering research articles and research theses: Advanced academic literacy and relations of power". English for Academic Purposes 5: 19–36.

Martin, James R (2000). "Analysing genre: Functional parameters". In: Christie, Frances/Martin, James R. (eds.) (2000): Genre and institution: Social progress in the workplace and school. London, Continuum: 3–39.

Okamura, Akiko (2008): "Use of citation forms in academic texts by writers in L1 & L2 context". The Economic Journal of Takasaki City University of Economics 51/1: 29–44.

Paltridge, Brian (2002): "Thesis and dissertation writing: An examination of published advice and actual practice". English for Specific Purposes 21: 125–143.

Pecorari, Diane (2003): "Good and original: plagiarism and patchwriting in academic second-language writing". Journal of Second Language Writing 12: 317–345.

Pecorari, Diane (2006): "Visible and occluded citation features in postgraduate second language writing". English for Specific Purposes 25: 4–29.

Petric, Bojana (2007): "Rhetorical functions of citations in high- and low-rated master's theses". English for Academic Purposes 6: 238–253.

Samraj, Betty/Monk, Lenore (2008): "The statement of purpose in graduate program applications: Genre structure and disciplinary variation". English for Specific Purposes 27: 193–211.

Shooshtari, Zohreh G./Jalilifar, Alireza (2010): "Citation and the construction of disciplinary knowledge". Journal of Teaching Language Skills 2/1: 45–66.

Swales, John (1986): "Citation analysis and discourse analysis". Applied Linguistics 7/1: 39–56.

Thompson, Geoff/Ye, Yiyun (1991): "Evaluation in the reporting verbs used in academic papers". Applied Linguistics 12/4: 365–382.

Thompson, Paul (2001): A pedagogically-motivated corpus-based examination of PhD theses: Macrostructure, citation practices, and uses of modal verbs . Unpublished PhD Thesis, University of Reading.

Thompson, Paul (2005): "Points of focus and position: Intertextual reference in PhD Theses". English for Academic Purposes 4: 307–323.

Thompson, Paul/Tribble, Chris (2001): "Looking at citations: Using corpora in English for academic purposes". Language Learning and Technology 5/3: 91–105.

White, Howard D. (2004): "Citation analysis and discourse analysis revisited". Applied Linguistics 25/1: 89–116.

Wohlin, Claes (2008): "An analysis of the most cited articles in software engineering journals". Information and Software Technology 50/1: 3–9.

Verbs found in verb controlling citations in MA theses

|

Argue (18) |

Attribute(1) |

Divide(1) |

|||||

|

Conceptualize(3) |

Analyze(1) |

Hold(2) |

|||||

|

Claim (16) |

Write(2) |

Hope(1) |

|||||

|

Adopt (1) |

Comment(1) |

Use(5) |

|||||

|

Point out (15) |

Acknowledge(4) |

||||||

|

Posit(2) |

Refer to(6) |

||||||

|

Stress(3) |

Identify(5) |

||||||

|

Suggest(18) |

Support(3) |

||||||

|

Say(4) |

Confirm(2) |

||||||

|

Maintain (21) |

Provide(1) |

||||||

|

Emphasize(5) |

Pinpoint(6) |

||||||

|

Define(36) |

Discover(1) |

||||||

|

Believe(23) |

Make it clear(1) |

||||||

|

Consider (10) |

Make endeavor(1) |

||||||

|

State(46) |

Hypothesize(3) |

||||||

|

Distinguish(1) |

Show(3) |

||||||

|

Underscore (2) |

Compare(3) |

||||||

|

Remark (2) |

Add(5) |

||||||

|

Introduce (4) |

Advise(3) |

||||||

|

Cite (2) |

Attempt to(3) |

||||||

|

Put (5) |

Look at(3) |

||||||

|

Put forward (1) |

Study(4) |

||||||

|

Indicate (2) |

Investigate(6) |

||||||

|

Express (3) |

Explain(2) |

||||||

|

Observe (3) |

Initiate(3) |

||||||

|

Recognize (1) |

Conduct(3) |

||||||

|

Contends (7) |

Assumed(3) |

||||||

|

Declare (3) |

Find(7) |

||||||

|

Certify (1) |

See(3) |

||||||

|

Approve (1) |

View(3) |

||||||

|

Regard (4) |

Reject(1) |

||||||

|

Mention(7) |

Examine(2) |

||||||

|

Describe (4) |

Report(4) |

||||||

|

Classify (4) |

Develop(2) |

||||||

|

Offer (2) |

Work out(2) |

||||||

|

Recall(1) |

Advocate(2) |

||||||

|

Assert(4) |

Present(4) |

||||||

|

Announce(1) |

Count out(1) |

||||||

|

Notify(1) |

Term(1) |

||||||

|

Propose(4) |

Elaborate(3) |

||||||

|

Conclude(2) |

Arrive(3) |

||||||

|

Call(4) |

Credit(3) |

||||||

|

Note(9) |

Recommend(3) |

||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Stance in Verbs Integral Citations in MA theses