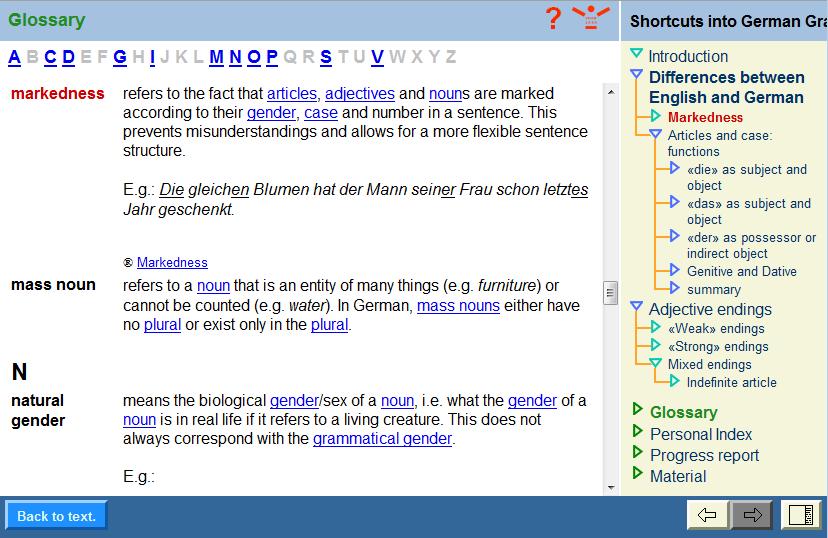

Figure 2: Glossary

German is notorious for its grammatical difficulty. But is this notoriety deserved – and on what is this judgment based?

Every language has its own peculiarities, which may be more or less problematical to any given learner. German's bête noire is its inflectional system and particularly its case and gender endings to indicate grammatical roles – but is this any more difficult than vowel harmony in Hungarian and Finnish, with the extra complication of Finnish having fifteen cases as compared with German's four? Our contention, hardly a new one, is that with an understanding of a few basic facts about the structure of German and the application of a restricted set of forms German needs to be seen as no harder than any other tongue. This paper thus takes a broad-brush approach: it is better to get most right rather than nothing, hence the 'percentage' approach.

So where's the mystery?

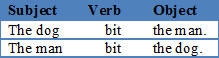

English is a linear language, i. e. grammatical function is largely determined by an element's position in the sentence, i. e. by word-order.

The use of the same words in a different order in a linear language creates a meaning change, formulaically:

Word order change → Meaning change

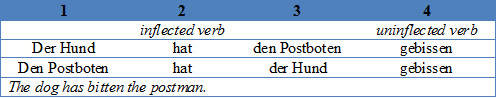

German is essentially non-linear, the basic rule of sentence structure being that the inflected, finite, verb occurs in second position in the simplex declarative sentence, and the uninflected verb, should there be one, occupies the final position. The noun phrases can rotate round the inflected verb, but do not change the meaning:

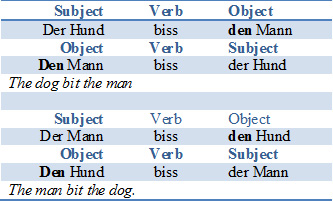

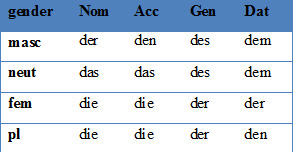

The function of the noun phrases is indicated by the endings of the articles:

der indicates [+ masculine], [+Subject], whilst den indicates [+ masculine], [+ Object]

Formulaically: Ending change → Meaning change

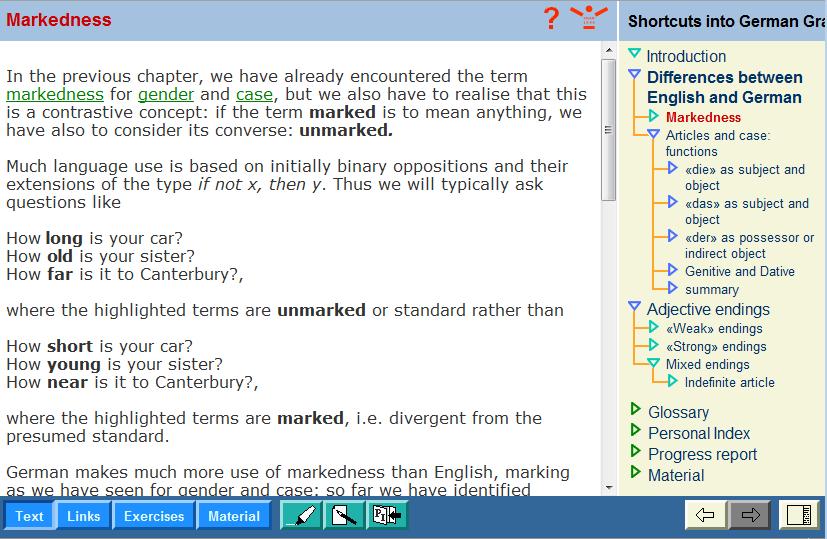

The principle of markedness is particularly salient in German, but let us first look at the concept using English examples.

Initially markedness involves binary oppositions, e.g. 'if not x, then y'. E. g.: the utterance of the first of each of the following pairs of sentences as the introduction of a decontextualised question is more normal than that of the second:

| How long is your car? | vs. | How short is your car? |

| How old is your sister? | vs. | How young is your sister? |

| How far is it to Wanne-Eickel? | vs. | How near is it to Wanne-Eickel? |

'long', 'old', and 'far' represent the norm, or the expected criteria, the old or unmarked information.

'short', 'young' and 'near'tend to be the marked form

used to indicate deviations from that norm, or the other end of the spectrum

unless the determining criterion has already been mentioned,

e. g. Dortmund is quite near to Wanne-Eickel → How near

is it to Wanne-Eickel?

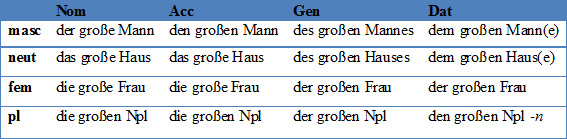

In German case and gender are marked by endings: in this instance the definite article does the marking, leaving only two 'weak' endings -e and -en in the adjective.

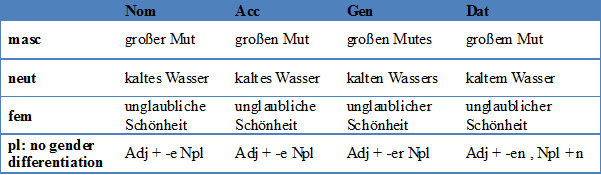

If there is no article to mark case and gender or the article marks unclearly, then the adjective has to do the job: but the number of forms increases from 2 to 5: -er, -en, -em, -es, -e:

Note now that the number of forms increases from 2 to 5: -er, -en, -em, -es, -e, but even then that is only an increase of three: -en, -em, and -es over and above the already present -e and -en. So no reason to panic.

Once the principles of case and gender marking are grasped the source of forms is close at hand: indeed they are prototypically something almost every non-speaker of German knows (of) and can parody: der/die/das. Once the paradigm is learnt, parrot-fashion if necessary –perhaps a pedagogically politically incorrect but most effective modus operandi, all the necessary endings are available, and can be hooked on to the adjective depending on whether the two weak or fivestrong endings are required as predicated by the presence or absence of a preceding article, or when there is ambiguity, for example when ein or kein, eine or keine fail to indicate whether nominative or accusative neuter or feminine respectively are specified, at which point a knowledge of German genders – a necessity in any case – comes into play.

Purists might remark at this point that some fine-tuning may be necessary, pointing out that endings derived from der/die/das need some slight adjustment, as they are not added to a stem d-. Rather they take on different forms recognisable from the der/die/das paradigm. More accurately, then, it should be said that they are the endings which are tacked on to the stems of the demonstratives dieser/diese/dieses [dies-], jener/jene/jenes [jen-] and the universal quantifier jeder/jede/jedes [jed-]. However, this remark, whilst undoubtedly true, presupposes a level of grammatical awareness in the learner which given the nature of the problem at this stage probably does not exist and the simplicity of learning – yes, learning – and applying one paradigm der/die/das suits the initial purpose of getting endings right most of the time – the percentage approach. Once a more sophisticated level of grammatical awareness has been reached the principle can easily be refined – if indeed this is necessary.

Very often, though, everything works fine when discussing the grammar in class but by the next week, the uncertainties are back. Clearly, then, there is a need for more than the toolbox itself: there is a retention problem.

By experience, when students are told to go off and "just learn the grammar", only very few of them have enough learning strategies and qualitative resources at hand to know how to do it. Grammar books often provide answer sheets but even then it is not clear whether the students have understood the concept or whether, almost by mistake, they just happened to get the form right. The learning process relies heavily on interaction and exchange and computer feedback can at least to some degree take on the role of a tutor – that is, if it is programmed sensibly. It should also inculcate good learning habits and strategies in the learner.

It is at this point that a knowledge of common problems enabling the teacher/programmer to predict the misapprehensions and errors of a specific target group comes into play. When using learning modules for self-study purposes, it is important to bear in mind the student's interaction with the software. Since this is only a one-way interaction, the pre-programmed feedback must be as comprehensive as possible in order to sufficiently explain the reason for the mistake, yet be concise enough so that it will still be read. This is not without its problems but compared to a traditional classroom setting allows the learner to become much more intensively engaged with the material and therefore fosters deep learning. To this end and thus to reinforce the learning process it is necessary to make available exercise, reference and terminological material, not only on the selected topic itself but also associated factors, for example articles, case, gender and word-order.

In order to combat the retention problem mentioned above, we looked for a way to present the theory to our students in an accessible and engaging way and decided on creating an online learning module to be made available via the University of Kent's virtual learning environment moodle (The open source learning management system can be downloaded for free at www.moodle.org [accessed July 26, 2012]). The integration of moodle into teaching is part of the University's e-learning strategy to support more flexible learning and to enhance the student learning experience. All teaching modules are available on moodle and can be accessed anytime and anywhere, on or off campus. The students log in to the learning environment using their student logins, no further software needs to be installed nor need accounts be created with other providers. Moodle is used extensively in the German language courses, both as a repository for classroom material and further resources but also for interactive tasks. Students are therefore used to the platform and can revisit the learning module as many times as they desire for the rest of their studies at Kent.

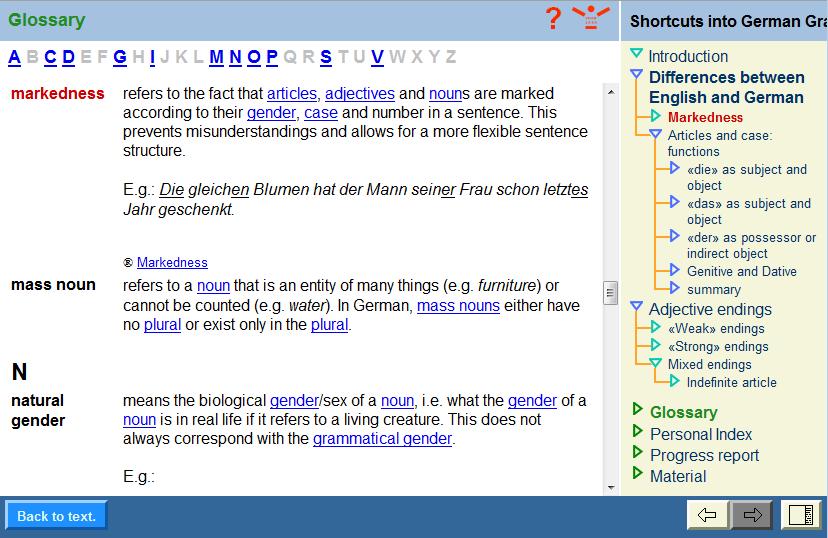

In our search for a suitable design and software for such a learning module our choice fell on the free authoring software Studierplatz 2000, which was developed as part of a programme funded by the German Ministry of Education and Research (more information: http://studierplatz2000.tu-dresden.de/asp/index.asp?fu=1&ta=0,0&up=1 [accessed July 26, 2012]). The html-based software makes it possible to easily distribute it online and is characterised by a most user-friendly structure as regards both the user and the programmer. The interface is attractive, easy to understand (Figure 1) and provides the learner with further help, for instance in the form of a glossary (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Glossary

The content of the module is presented in a clear outline which not only provides learners with a structure and guidance on how to approach the material but also allows them to jump to a specific chapter of interest. Glossary items are hyperlinked in green in the instruction text and can also be accessed by clicking on "Glossary" in the menu on the lower right hand side. At any point, the button "Back to text" takes the student back to the chapter and screen on which they were working before.

From the teacher's point of view, the program allows an extremely flexible approach in design. Almost any type of media can be included and the exercises too can be enhanced through pictures, video or audio files. The available exercise formats include, amongst others, multiple-choice questions, drag-and-drop exercises or gap-filling exercises and, depending on how they are used, can be designed as practice drills or more complex cognitive exercise formats.

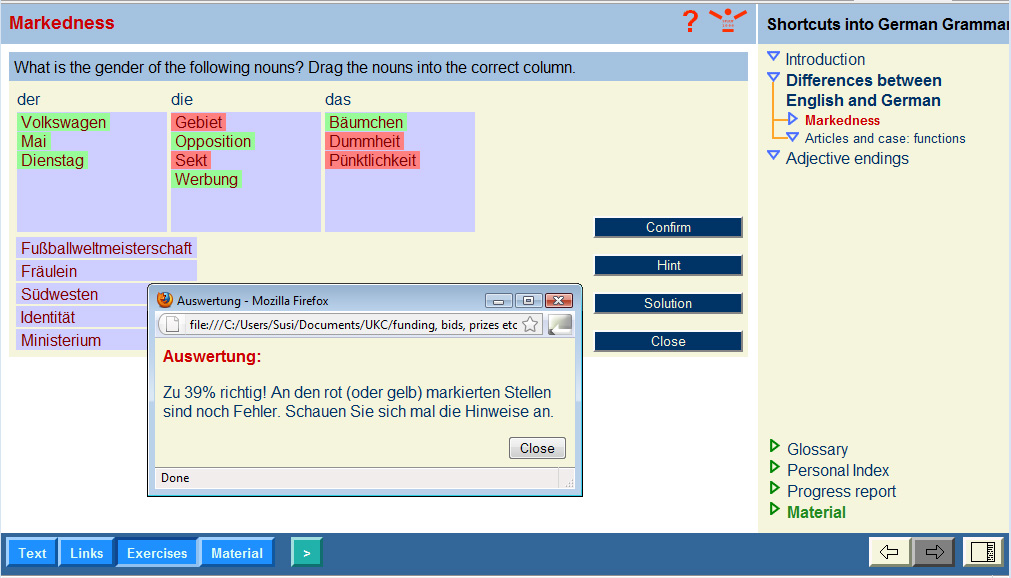

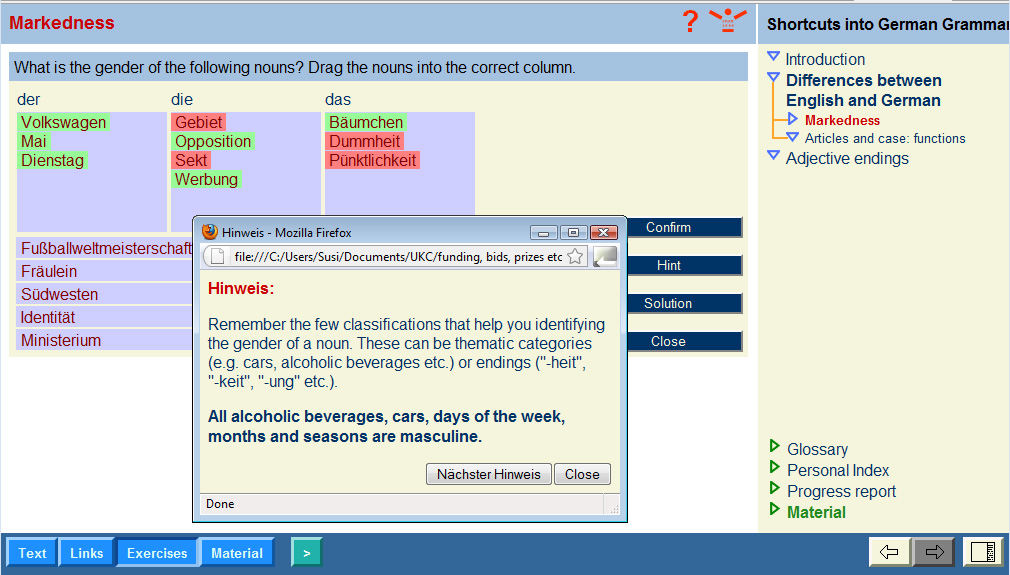

More important yet, the pedagogical concept behind the program is based on a critical self-reflection which means that wrong answers are not immediately corrected but learners are encouraged to understand where they went wrong, for instance by using pre-programmed hints (Figure 3). This puts learners in control of their own learning and provides individual feedback in a way which is not possible in a traditional class setting.

With the use of pre-programmed hints, the learner is further encouraged to find the correct answer. And since the hints have to be phrased and programmed individually, they can be closely linked to the instructional material or in the case of the screenshot (Figure 4) to supplementary material that is provided within the program. Recalling learning strategies as shown in Figure 4 helps learners to solidify their knowledge and equips them with necessary strategies which are useful in order to master other grammatical topics as well.

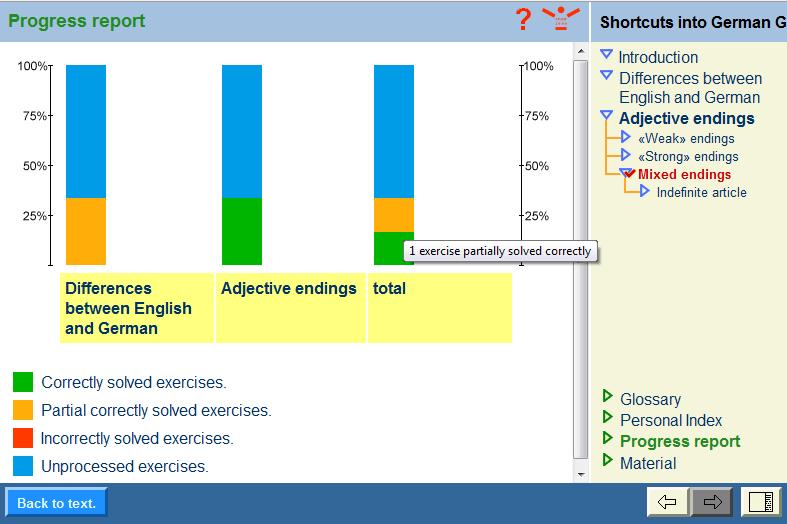

Furthermore, learners can self-monitor their progress by using the reports the program provides (see Figure 5), which also functions as an important motivational factor in the learning process. The built-in progress report shows how many exercises have already been attempted, how many of them were solved correctly and how many incorrectly. This is extremely helpful in order to self-assess one's understanding of the subject matter and also to gain an overview of which chapter might need to be revisited again. Students can identify their own strengths and weaknesses and use that information to make them aware of their own learning needs and to set new learning goals.

At this stage the 'Shortcuts'program consists of a customised learning module based on the concept of markedness in German covering topics such as noun gender, case forms, article use, word order and adjective endings. Using a variety of interactive exercises and further resources and guiding the learner in the learning process, a learning module has been created that engages learners and helps them to consolidate their knowledge as well as to expand their linguistic awareness and language capability. By providing pre-programmed feedback learners gain more insight into their learning and are able to become more autonomous life-long learners.

Further projections see the markedness principle and attendant theoretical and learning modules being extended to other areas of German grammar. The approach and program can also be applied to other languages.

Duden-Redaktion (2006): Duden-Grammatik. Mannheim: Duden-Verlag.

Durrell, Martin (2002): Hammer's German Grammar

and Usage. 4th edition. London:

Arnold.

Eisenberg, Peter (1998): Grundriss der deutschen Grammatik 1 & 2. Stuttgart: Metzler.

Gagné, Robert et al. (2004): Principles of Instructional Design. 5th edition. Stamford, Connecticut: Wadsworth Publishing.

Helbig, Gerhard/Buscha, Joachim (2001): Deutsche Grammatik: ein Handbuch für den Ausländerunterricht. Berlin: Langenscheidt.

Horton, William (2006): e-Learning by Design. San Francisco: Pfeiffer.

Mayer, Richard (2005): The Cambridge Handbook of Multimedia Learning. Cambridge: CUP.

Mayer, Richard (2009): Multimedia Learning. Cambridge: CUP.

Rösler, Dietmar (2004): E-Learning Fremdsprachen – eine kritische Einführung. Tübingen: Stauffenburg.

Twain, Mark (1880): The Awful German Language, Appendix D to A Tramp Abroad.

Zifonun, Gisela et al. (1997): Grammatik der deutschen Sprache. Berlin: de Gruyter.