Kinship terms are, above all, known for their possible complexity when it comes to denoting the exact kind of relationship between people: where one language, like English, just has the term 'uncle', another might have one for father's older brother, one for father's younger brother, one for the husbands of father's sister, and of course completely different words for the same kind of relation on the mother's side. Kinship systems have been well described, one of the earliest and certainly the most famous study being that of Lévi-Strauss (1949/1969). These terms, however, cannot only be used in order to describe more or less complicated degrees of relationship within an extended family. They can, apart from that, be found in rather unexpected circumstances, being used in order to either address (vocative use) or speak about (referential use) non-related human beings. “Vocative uses, by definition, must have second-person referents, referential uses, on the other hand, may have first, second, and third person referents: in certain languages and certain social contexts, kin terms may be used in lieu of first and second person pronouns.” (Dahl/Koptjevskaja-Tamm 2001: 203). Probably the best-known language of this sort is Mandarin (cf. e. g. Song Xuan 1997). However, the phenomenon is far from being as “exotic” – at least from an English-speaking point of view – as the mentioning of Chinese might lead us to think: vocative and referential uses of kinship terms cannot only be found in numerous non-Indo-European languages like Vietnamese, Thai, Uygur or Turkish; it also occurs in languages like Persian, Serbian or even German. Still, the functions of this kind of reference are quite diverse.

The following examples, taken from modern Serbian,1 shall be used as the first illustration for some of the pragmatic functions kinship terms may fulfil.

(a) Addressing someone non-kin as 'brother', 'sister':

'Brother': young man greeting a friend (routine salutation):

| (1) | Ma | gde | si | bre | brate! |

|

| but | where | are-2nd sg. | [particle] | brother-VOC |

'Sister': address line from an internet site:

| (2) | jao | sestro | slatka | |||

| [interjection] | sister-VOC | sweet | ||||

| šta | sve | imam | da | ti | ispričam2 | |

| what | all | have-1st sg. | that | you-DAT | tell-1st sg. |

(b) Addressing someone non-kin as 'son':

An older woman to younger one (personal observation):

| (3) | Nemoj | se | ljutiti | sine! |

| don't | reflexive pronoun | upset | son-VOC |

(c) Addressing or referring to someone as baba 'granny':

Market-woman to costumer, referring to herself (personal observation):

| (4) | Babi | treba | novac | |

| Granny-DAT | is | necessary | money |

From an internet posting:

| (5) | a | ti | si | glupa | baba |

|

| and | you | are | stupid | granny |

|

| koja | zna | samo | ružno | govoriti3 |

|

| who | knows | only | ugly | to talk |

Song text by Ajs Nigrutin:

| (6) | neka | baba | na | reklami |

| some | granny | on | commercials | |

|

| trlja | sise | besno4 | |

|

| shakes | breasts | ferociously | |

(d) Referring to someone as 'uncle' or 'aunt':

| (7) | Dobri | čika | Fića | i | njegov | fića5 |

|

| good | uncle | Fića | and | his | Fiat |

From a political discussion on the internet news site of radio B92:

| (8) | Cim […] | neki | cika | iz | Vashingtona |

|

| As soon as | some | uncle | from | Washington |

|

| kaze | da | je | bilo | dosta.6 |

|

| says | that | is | been | enough |

From internet forums/blogs:

| (9) | Rečeno | je | da | taj | čikica (Sergej Polonski) | treba7 |

|

| Said | is | that | that | uncle-DIM (Sergej Polonski) | shall |

| (10) | kao | neka | dosadna | strina8 |

|

| like | some | annoying | aunt |

| (11) | Tetkice | opet | skuvale | loshu, | tanku | kafu9 |

|

| Aunt-DIM-PL | again | cooked | bad | thin | coffee |

Let us try a first rough analysis of this little collection. It shows various cases where kinship terms are being used in order to talk to or about non-related persons, even strangers. As for the degree of politeness10 of these terms, referential as well as vocative uses can carry very positive connotations: addressing a male friend as brat 'brother' as in (1), a woman as 'sweet sister' as in (2), or an older adult as 'uncle' in (7) is obviously a polite or even endearing way to address or refer to these people. The closest parallel in English might be addressing a stranger as darling or love, although it is of course not possible to refer to a third party in this way.

A closer look at the contexts of sentences like (1), (2), and (7) shows that while 'brother' and 'sister' are used when communicating on an intimate and informal level, 'uncles' are addressed as such even in a more distant style. For example, it would be customary for children, adolescents and young adults to address the father of a friend as čika 'uncle'. Consequently, the meaning of the word began to change, and over time has developed from denoting a relative to politely addressing and referring to any older gentleman.11 However, it clearly was originally a kinship term (cf. Skok 1971: s. v. čika). In all these cases, one might of course assume that by “adopting” someone, and thereby making him or her a member of their family, the speaker establishes a close relationship and shows affection. That this should be perceived as friendly is not really very surprising.

However, this is clearly not the whole story. If čika is Vashintona ['uncle from Washington'] in (8) is to be considered a term of affection in the given context, then its use must be highly ironic. As for čikica [uncle-DIM] Sergej Polonski in (9), the Russian millionaire was 36 at the time of the posting, and could therefore hardly be considered an older gentleman. There must obviously be some additional connotations. In order to find out what they are, let us first consider the other cases.

In the examples given above, we find not only uncles, but also aunts and 'aunties'. Tetka or strina (both meaning ‘aunt’, see below) are always applied pejoratively, whereas in everyday language use, the word tetkica 'auntie', as observed in (11), means a charwoman. In certain places and situations, e. g. in university buildings, the charwomen are also expected to make coffee – which explains the otherwise seemingly rather strange sentence. What may have started out as an affectionate term now merely refers to a job and carries low, if any, emotional connotations. Therefore, at first sight, this example does not help much when it comes to determining the kind of connotation kinship terms carry. It is, however, interesting to see which kinship term it is that has been transformed into the job title.

Older women can obviously refer to themselves as baba 'granny', as is illustrated by examples (3) and (4). It is also possible to call an older woman majka 'mother' in an endearing way.12 But what is even more interesting is the fact that an older woman can address a younger one as sin 'son', as is the case in example (3), or as sinko 'sonny'.13 In everyday conversation, this clearly serves as a term of affection, paralleling English forms of address like dear. It might of course seem strange to use this term for a female, who one might expect to be called 'daughter' instead. This is, however, impossible: a stranger cannot be addressed as ćerko or kćeri ('daughter'). But since sons are worth so much more than daughters in a patriarchal society, it is obviously better to be considered a son than a daughter, and this additional value makes the expression even more affectionate: you, the speaker implies, are a very valued younger member of my family. In a similar way, the market-woman in (4) is only stating that she is older than her customer, but, at least in a way, asking for their affection and respect by making herself part of their family. This seems rather straightforward. But what about examples (5) and (6)? In both cases, the context makes it clear that the term baba does not refer to an older woman – and that it is used pejoratively. This is quite the contrary to being polite, so the question remains of how the same means of communication can have completely opposite effects.

Taking a look at other parts of the world, one of the languages that comes to mind because it shows a very regular use of kinship terms in everyday life is modern Chinese. Here, kinship terms are so widespread that they are introduced in textbooks for learning Chinese as a foreign language. For instance, the term āyí 'auntie – a term of address that can be used when speaking to the mother of a friend – is even used in a textbook without any special explanation, implying that the use and meaning is made obvious by its context (cf. Yang 2007: 28f.). The application of kinship terms in everyday conversation with non-kin is indeed an often discussed characteristic of modern Chinese (cf. e. g. Song 1997). Good friends can call each other dàjiě ('eldest sister') or mèimei ('younger sister'), depending on the age difference, and a young girl might affectionately be called xiaomèi ('little sister') by a stranger. An older gentleman may be addressed as well as referred to as shūshu 'uncle' (on the father's side) – the list goes on and on.

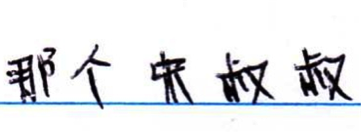

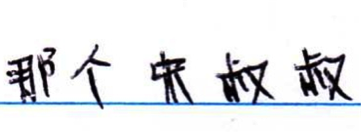

This kind of address or reference is widespread and very much alive

in everyday use. The following illustration (fig. 1) shows a part of a

letter from a school girl, referring to a high ranking police officer,

Mr. Song, who had helped her establish contact with the author of this

text. She did not know him well at all, and there is a great social gap

between the poor village girl and the high-ranking functionary. However,

she refers to him as na ge Sòng shūhu 'this uncle Song':

Fig. 1: 'this uncle Song' (from a personal letter)

In Chinese, or so it seems, almost every kinship term may be used in order to refer to non-kin. On the other hand, most speakers of languages like English or German would deny that anything of this kind is also possible in their own language. However, the possibility of referring to strangers by kinship terms is by no means completely absent from Germanic languages; it is just that most speakers usually are not aware of it.

The first thing that comes to mind is that when talking to children, speakers of German may say something like:

| (12) | Gib | der | Tante | das | schöne | Händchen! |

| give | the | aunt | the | nice | hand-DIM |

| (13) | Geh nicht | mit | einem | fremden | Onkel! | |

| don't | go | with | a | strange | uncle |

Especially in cases like (13), it is quite obvious that it is not a

real uncle the speaker is referring to, but rather any male adult –

which is of course the same principle that operates in (12).

However, something completely different seems to be going on in examples

like (14):

| (14) | sie | mich | dann | als | Hysterische | Tante | bezeichnen16 |

|

| they | me | then | as | hysterical | aunt | call |

The given context made it clear that the speaker is not referring to herself as the actual aunt of someone – on the contrary: she is talking about her behaviour as a mother – but rather to the negative prototype of a hysterical female. The same sort of negative prototype can be found with other kinship terms, as well, as the following examples (15–18) illustrate:

| (15) | plötzlich | kommt | da | so ne | Oma | aus | dem | Gebüsch | geschossen17 |

| suddenly | comes | there | such a | granny | out | the | bushes | fired |

| (16) | so ein | blöder | Opa, | der | mit 50 | über | die | Landstraße | tuckert18 |

| such a | stupid | granddad | who | with 50 | over | the | country road | chuggs |

| (17) | Dann | is | ihr | so'n | Muttchen | voll | hinten | draufgefahren.19 |

| then | is | her | such a | mommy | fully | behind | collided |

| (18) | dann | fuhr | mir | so ne | Mutti | im | Touran | vor | die | Schnauze20 |

| then | drove | me | such a | mom | in a | Touran | before | the | kisser |

We meet with disagreeable grannies and granddads, and with unappealing moms and mommies. However, most interestingly, there are no daddies with negative connotations to be found – or at least not in the standard language. In Swiss German dialects, however, it is possible to say something like ah, ha scho wider so ne aute päppu vor mir or ah, ha scho wider so ne aute vättu vor mir ('ah, there is an old daddy in front of me again’), using aute päppu or aute vättu (both meaning 'old daddy') in a pejorative way.21

As has been stated before with reference to Dahl/Koptjevskaja-Tamm (2001: 203), kin terms can be used in lieu of first and second person pronouns. This is clearly the case in examples like (4), where a woman is referring to herself by using baba 'granny' instead of ja 'I'. One might be inclined to argue that something similar happens in examples (1)–(3). However, the kinship terms in these utterances are used in the vocative case and can therefore not be considered as second person pronouns, since vocatives are not part of the syntactical structure of a sentence. Therefore, the resemblance is only superficial, but they are still examples of addressing someone non-kin as kin with good intentions.

Obviously, however, the use of kinship terms can also be meant to belittle the person they refer to, as examples like (5) and (6) or (13)–(17) show. But why is this so, and which terms can be used in order to convey which meaning?

In order to create a tertium comparationis between the languages in

question, the following very simplified schematic of general kinship

relations shall be used (fig. 2). It is by no means complete – it

contains, for instance, no terms for the husbands and wives of the

sisters and brothers of one's parents – but it shows the relations

within the narrower family.

| mother's father | mother's mother | father's mother | father's father | ||

| mother's elder sister | mother's elder brother | father's elder sister | father's elder brother | ||

| mother's younger sister | mother's younger brother | mother | father | father's younger sister | father's younger brother |

| elder daughter | elder son | ||||

| elder sister | elder brother | ||||

| younger sister | younger brother22 | ||||

| younger daughter | younger son | ||||

Fig. 2: Kinship relations in general

If we apply the schematics to Serbian and print all terms bold that can be used either in order to address someone or in order to refer to a third person, we get the following picture (fig. 3):

| = deda, dedica | = baka; baba, babica | = baka; baba, babica | = deda, dedica | ||

| = tetka | ujak | mater, majka; mama

|

otac; tata

|

= tetka | stric, čiča → čika |

| kćer/kćerka | sin, sinko | strina ('wife of stric') |

|||

| sestra | brat | ||||

Fig. 3: The use of kinship terms in Serbian

Where there is more than one term given, the first one is always the one that would be used in literary language (like baka 'grandmother', mater 'mother', otac 'father'), whereas the following ones are mostly more familiar terms (like baba 'granny', tata 'daddy') or even diminutives (like sinko 'son-DIM'). As we can see, apart from some more formal terms, which are substituted by more familiar ones, it is only ujak ('mother's brother') that cannot be used in order to refer to non-kin.

In German (fig. 4), there are considerably fewer kinship terms that can be used in order to refer to non-kin:

| = Großvater, Opa | = Großmutter, Oma | = Großvater, Opa | = Großmutter, Oma | ||

| = Tante | = Onkel | Mutter, Mama, Mami, Mutti, Muttchen | Vater, Papa, Papi | = Tante | = Onkel |

| Tochter | Sohn | ||||

| Schwester | Bruder | ||||

Fig. 4: The use of kinship terms in German

Again, where there is more than one term given, the first one is the most neutral one, whereas the following ones belong to a more familiar register or are terms of endearment (Mutti, Mami).

In comparison, the Mandarine Chinese schematics, greatly simplified and by no means complete, would look like this (fig. 5):

| mother's… | father's… | ||||

| father 外祖父 waizufu; 姥爷 laoye | mother 外祖母 waizumu; 姥姥 laolao | mother 祖母 zumu; 奶奶 nainai; 婆婆 pópo, | father 祖父 zufu; 爷爷 yeye |

||

|

brother

舅父 jiùfù 娘舅 niángjiù 舅舅 jiùjiu |

eldest sister

大姨 dàyí23 |

mother

母亲 muqin 妈妈 mama

|

father

父亲fuqin 爸爸 baba |

姑姑 gūgu

姑妈 gūmā 姑母 gūmǔ24 |

elder brother

伯伯 bóbo, 大伯 dàbó 伯父 bófù 大爷 dàye |

|

sister (elder or younger)

姨母 yímǔ 阿姨 ayi |

daughter

女儿 nüer [丫头 yātou ] |

son 儿子 erzi |

younger brother

叔叔 shūshu, 大叔 dàshū, 叔父 shūfu |

||

|

elder sister

姐姐 jiě(jie); 大姐 dàjiě |

elder brother

哥哥 gē(ge); 大哥 dàgē |

||||

|

younger sister

妹妹 mèi(mei); 小妹 xiaomèi |

younger brother 弟弟 dìdi; 老弟 laodì |

||||

Fig. 5: The use of kinship terms in Chinese

In order to get a more extensive picture, let us consider two more languages. Fig. 6 shows Vietnamese, and fig. 7 Uygur.

| mother's... | father's... | ||||

| father ông ngoại | mother bà ngoại | mother bà nội | father ông nội |

||

| sister dì | brother cậu | elder sister bác (gái)25 | elder brother bác (trai)26 |

||

| mother mẹ | father cha | younger sister cô | younger brother

chú

|

||

| daughter con gái |

son con trai | ||||

| elder sister chị (gái) | elder brother anh (trai) | ||||

| younger sister em (gái) | younger brother em (trai) | ||||

| younger daughter con gái thứ | younger son con trai thứ | ||||

Fig. 6: The use of kinship terms in Vietnamese27

| mother's... | father's... | ||||

| father çong dada, bowa | mother çong apa, moma |

= | mother çong apa, moma | father çong dada, bowa |

|

| older brother tağa, çong dada/ata ('big uncle') | older sister hamma, çong apa/ana ('big aunt') | older sister hamma, çong apa/ana ('big aunt') | older brother tağa, çong dada/ata ('big uncle') |

||

| younger brother tağa; kiçik dada/ata ('little uncle') | younger sister hamma; kiçik apa/ana ('little aunt') | mother apa, ana | father dada, ata | younger sister hamma; kiçik apa/ana ('little aunt') | younger brother tağa; kiçik dada/ata ('little uncle') |

| daughter qīz |

son oğul |

||||

| elder sister aça, hädä |

elder brother aka, ağa |

||||

| younger daughter uka, singil | younger son uka, inī |

||||

Fig. 7: The use of kinship terms in Uygur28

The data show clearly that the use of kinship terms is a widespread phenomenon, occurring in different kinds of languages and cultures. However, the number of kinship terms that can be used in such a way is by no means the same, and the connotations that come with this kind of language use are surprisingly divergent. In Uygur, Thai and Vietnamese, kinship terms, whether used in order to address someone or in order to refer to someone, are always respectful and polite – and almost all of them can be applied to refer to someone non-kin. The same is the case in Chinese. Here, some of these terms have developed a specific meaning, like dà gē 'eldest brother', which may be used in order to refer to a gangster boss, or xiǎo jie (literally: 'little elder sister'), which was originally used to address a younger woman, i. e. in the sense of 'Miss', and now can mean 'prostitute' in some areas. However, these are clear cases of euphemisms, easily explained. The only way to use a Chinese kinship term with negative connotations would be to address someone older than oneself as 'younger brother' or 'younger sister'. But obviously this is not a problem that results from the kinship terms as such, but from their inappropriate use.

However, things begin to look quite different when we take a look at the European languages that have been considered above. While in Serbian the use of kinship terms is neutral to polite in most cases, it can also be belittling to outright rude; and in German, it is mostly rude. In these languages, it is also only the more informal, familiar terms like 'granny' or 'mommy' that can be used to refer to strangers, not the more formal ones like 'mother' or 'grandmother'.

If we take a closer look, we find that there is a gender difference correlating with the connotations of kinship terms. This can be illustrated quite well in Serbian:

Terms for male relatives and their connotations:

term of endearment: brat 'brother'; sin 'son'

respectful: otac 'father' (very rare)

respectful OR slightly pejorative: čika 'uncle', čikica 'uncle' (DIM)

respectful OR pejorative: deda 'granddad', dedica 'granddad' (DIM)

Terms for female relatives and their connotations:

term of endearment: sestra 'sister'

respectful: majka 'mother'

neutral to pejorative: baba 'granny', babica 'granny' (DIM); tetka 'aunt'

pejorative: strina 'aunt'

special use: tetkica 'aunt' (DIM) = 'charwoman'

While terms for male relatives can be used in a respectful way and are slightly pejorative at worst, terms for female relatives are respectful only in the case of 'mother'. Otherwise, they are neutral at best and quite pejorative in other cases. Only 'brothers' and 'sisters' reside an the same level of respect, although it should be noted that males are called brate ('brother-VOC') much more often than women are called sestro ('sister-VOC' or, more often, sestro slatka ('sister-VOC sweet'). This, of course, matches the fact that in order to address a young woman in an endearing way, one has to call her 'son', not 'daughter' – femaleness bears a certain amount of negative connotations from the beginning. With both genders, it seems to be especially condescending or even rude to call a younger person 'uncle/aunt' or 'granddad' or 'granny'. Obviously, age is no longer considered to be something positive in this culture.

The Serbian society, while still showing some traits of the traditional collective society it used to be, is rapidly developing into an individualized society.29 For quite some time, Serbian society has been developing from a collectivistic structure, where extended families lived together in large groups of several generations, towards individualism, manifesting itself in a modern, urban type of individual lifestyle. This is obviously being mirrored by the use of kinship terms: while some of them still hold the older, respectful and/or endearing connotations they would have held in an extended family, others have begun to deteriorate, showing a new perspective on roles and kinship relations.

In the German speaking countries, the development from collectivism to individualism started much earlier and is therefore much more advanced. It is therefore not surprising to find that in German, kinship terms are neutral at best, and this only if used when speaking to a child. In all other contexts, they are distinctively pejorative. Again, there is a difference between the two genders:

Terms for male relatives and their connotations:

Onkel 'uncle': respectful to neutral when speaking to children

Opa 'granddad': pejorative

Terms for female relatives and their connotations:

Mutti, Muttchen 'Mummy': pejorative

Oma 'granny': pejorative

Tante 'aunt': respectful to neutral when speaking to children, otherwise pejorative

It turns out that in German-speaking countries, terms for female relatives are pejorative. Male terms can carry negative connotations, too, but seemingly only when they refer to much older persons (like Opa 'granddad'). One might be inclined to infer that it is bad to be either a woman or old (or in the worst case: both). It is also interesting to see that it is the more familiar, intimate expressions that are used. The additional insult apparently results from the fact that someone is not only treated as inferior, but at the same time addressed on a first name basis, so to speak, i. e. without the respectful distance common politeness would require.

In languages like Chinese, Vietnamese or Uygur, things are of course quite different. It seems convincing to assume that in these cultures, the development from collectivism to individualism, although it is most certainly taking place, has started more recently and has therefore not yet left its traces in the use of kinship terms. To sum up this process in a simple way: when societies move from collectivism to individualism, kinship terms move from respectfulness to disrespect.

Obviously, the use of kinship terms in order to refer to non-kin is polite in some, usually more collective societies, and pejorative in other, more individual ones. However, this does not answer the question why kinship terms are used at all. Why would this be so?

One might assume that it is nice and caring to “adopt” someone into one's family, therefore the use of such terms is perceived as polite. This is a convincing assumption as far as it goes. But why, then, should the same terms be used in order to belittle or even insult someone? It has been observed that only some of the kinship terms can be used in this way, and they all refer to either old or female family members (or those who are both at the same time). Still, if it is considered to be less than desirable to be old and/or female, it should be enough to call someone an old hag or its equivalent in the respective languages in order to insult them. Instead, they are “adopted” as grandmas.

The reason behind this seemingly strange linguistic phenomenon probably lies deeper within our basic perception of the world than one might be inclined to think at first. Corbett (2000: 56) was able to show that the extended animacy hierarchy underlying the marking of number in nouns and pronouns in the languages of the world moves from pronouns (1st, 2nd, and 3rd, in this order) to kinship terms, and only after that to 'human' in general. Obviously, in our basic conceptualization that underlies such phenomena, kin are perceived as being closer to us than the rest of humanity. If this is the case when it comes to expressing something as fundamental as number, it is of course not very surprising to find the same to be true in other domains, as well. Seen in this light, an 'old hag' would just be human; but a 'granny' is kin, and therefore comes to mind much more easily. This explains why, in the positive as well as in the negative sense, the expression that ranks higher in the hierarchy is used: if it is better, it is much better; if it is worse, it is much worse.

The use of kinship terms in order to address or refer to non-kin is a widespread phenomenon. Interestingly enough, these terms can be very polite (as they are in languages like Chinese) as well as very impolite (e. g. in languages like German). It could be shown that the two factors age and gender influence the connotations of a term. In the cultural concepts of all societies whose languages have been taken into consideration, it is good to be young and male. In some of them, however, it is considerably less desirable to be old and/or female. This slide towards impoliteness can especially be observed in societies that have developed into, or at least moved considerably far towards, individualism.

While it seems quite understandable that it can be considered friendly to 'adopt' someone into one’s family, it is somewhat confusing that we would still use kinship terms in a pejorative way. This seemingly strange fact can be explained by the fact that kinship terms play a role in other linguistic features, too, and rank high in the hierarchy of linguistic terms as a whole. In the hierarchy of number marking, they are the first nouns to receive number marking morphemes, and might be the only ones besides the pronouns. It can therefore be assumed that the same ranking phenomena play a role in the use of kinship terms for non-kin, too.

Brown, Penelope/Levinson, Steven C. (1987): Politeness. Some universals in language usage. London etc.: Cambridge University Press.

Corbett, Greville G. (2000): Number. Cambridge etc.: Cambridge University Press.

Dahl, Östen/Koptjevskaja-Tamm, Maria (2001): “Kinship in grammar”. In: Baroh, Irène/Herslund, Michael/Sørensen, Finn (eds.): Dimensions of Possession. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: 201–225.

Lévi-Strauss, Claude (1969): The Elementary Structures of Kinship. Rev. ed. London: Eyre & Spottiswoode.

Matica srpska (1967–1976): Rečnik srpskohrvatskoga književnog jezika. Novi Sad: Matica srpska.

Perović, Latinka (2000): “The Flight from Modernisation”. In: Popov, Nebojša (ed.): The road to war in Serbia: trauma and catharsis. Budpest/New York, Central European University Press: 109–122.

Song Xuan 宋宣 (1997). 现代汉语称谓词初探 [On terms of address in modern Chinese]. 贵州大学学报 1.

Skok, Petar (1971-1973/1988): Etimologijski rječnik hrvatskoga ili srpskoga jezika. 3 vols. Zagreb : Jugoslavenska Akademija Znanosti i Umjetnosti.

Watts, Richard J. (2003): Politeness. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Yang, Jizhou (2006): Hanyu Jiaocheng [Chinese Language Course] Book 2 Part 2. Beijing: Beijing Language and Culture University Press. 4th ed.

1 Most of the examples in this paper rely on personal observation by the author and by native speakers she has consulted. In some cases, internet sources have been used as well; these are always cited. However, this is not a corpus analysis, but a first approach to the problem, using exemplary data. back

2 http://www.sestroslatka.com, accessed January 17, 2012. back

3 The text goes on: i biti ljubomorna na nju što je uspješno završila karijeru……. (appr.: ‘and to be jealous of her who has successfully finished her carreer’). [http://www.pogledaj.name/comment/3476/ti-si-glupa-baba-koja-zna, accessed September 25, 2008]. back

4 The songtext goes on: Cvaj cvaj cvaj - nul nul nul / Nemachki debili, njima je to kul (appr.: ‘222-000 [in German]/ German idiots find this cool.’, thereby showing clearly that the text is referring to a prostitute advertising herself on night tv, not to an older woman. back

5 http://www.balkanphotocontest.com/index.php?menu=7&gID=5611&img=96112, accessed January 16, 2009. back

6 http://forum.b92.net, accessed January 16, 2009. The complete sentence was: Naravno, ruski tenkovi ce odmah biti zaustavljeni cim zazvoni telefon u Moskvi i neki cika iz Vasingtona kaze da je bilo dosta. (appr.: ‘Of course, the Russian tanks will stop at once as soon as the telephone rings in Moskow and some uncle from Washington says that enough is enough’). back

7 The complete contribution said: Rečeno je da taj čikica (Sergej Polonski) - treba da uruči ključeve od vile (u vrijednosti od cca 2 miliona EUR) Madoni za poklon. (appr.: ‘It is said that that uncle (Sergej Polonski) – shall hand over the keys to the villa (worth about 2 million EUR) as a gift to Madonna’; Sergej Polonski is a Russian millionaire, born in 1972.) [forum.cafemontenegro.com/showthread.php?p=1020649, accessed September 25, 2008]. back

8 http://www.creemaginet.com/sajt/stonsi-u-beogradu-malko-drugaciji-utisak, accessed June 5, 2011. The complete sentence was: Mene često optužuju da sam kao neka dosadna strina koja neprekidno i uporno traži falinke (appr.: ‘They often accuse me of being like a annoying aunt who constantly and insistently looks for fault’). back

9 http://www.popboks.com/forum, accessed January 16, 2009. back

10 During the past decades, there have been several attempts to define the term “politeness”, from Brown/Levinson (1987) to Watts (2003), to name but two important studies. For the purposes of this paper, however, further investigation into the nature of the phenomenon did not seem necessary. The degree of politeness of an expression has been based exclusively on the evaluation of native speakers who felt that an utterance was polite or impolite (or very much so). back

11 The Rečnik srpskohrvatskoga knjizevnog jezika gives one of the meanings of the word as: „[…] uopšte stariji čovek, čovek u godinama […]“ (‘older man in general, man of certain years’), stating twice that it is a term of affection (s. v. čika). back

12 Interestingly enough, though, when referring to a stranger, the vocative majko cannot be used, and the nominative majka is applied instead: Šta kažete, majka? (‘What do you say, mother?’); Kakva je paprika, majka? (‘How is the pepper, mother?’; examples: personal communication Aleksandra Bajazetović). back

13A personal experience might be used to illustrate this: The post mistress at the post office where the author of this text used to go in order to buy stamps always called her sinko. back

14 This particular sentence might not be used very often anymore in actual child raising; however, it can be found quite often as a quotation on the internet, see e. g. http://frauholz.wordpress.com/2010/04/14/kinder-knigge, Westfälische Nachrichten, Kreis Borken: Gib das schöne Händchen…, both accessed June 28, 2011. back

15 The use of ‘uncle’ and ‘aunt’ for strangers is not equally common in the different areas where German is spoken. To wit, it is more common in Germany than it is in Switzerland. back

16 http://www.parents.at/forum/showthread.php?p=6533135, accessed January 16, 2009; the full sentence was: Ich hab ja dann immer Angst bzw. Befürchtungen, dass sich mich dann als Hysterische [sic!] Tante bezeichnen (appr.: ‘I’m always afraid or have misgivings that they will call me a hysterical female’). back

17 http://www.wuff-online.com/forum/showthread.php?t=88463&page=17, accessed May 5, 2011. back

18 http://www.kaowner.de/forum/showthread.php/1492-Kurzstabantenne, accessed May 5, 2011. The complete sentence was: Erst gibt so ein blöder Opa, der mit 50 über die Landstraße tuckert, in dem Moment, in dem ich ihn überhole, ordentlich Gas (appr.: ‘First, this blockhead chugging along the country road at 50 [km/h] accelerates heavily at the very moment when I am passing him’). back

19 http://www.wordvomit.org/Vanilla_Yume/archiv12.html, accessed January 16, 2009. back

20 http://www.golf-6.com/golf-vi/317-topspeed-26.html, accessed May 6, 2011. The complete sentence was: Gestern auf gerader Strecke die 204 im Digitacho gehabt und dann fuhr mir so ne Mutti im Touran vor die Schnauze (appr.: ‘Yesterday I had 204 on my digital speedometer on a straight route and then this dumb Dora in a Touran cut in right in front of me’). back

21 Personal communication Gabriela Perrig. back

22 The gray background is used in order to mark the fact that these terms are on a different hierarchy level than the rest of the schematics: sons and daughters are brothers and sisters in reference to each other. back

23 Further ‘aunts’ on one’s mother’s side are: 舅母 jiùmu, 妗母 jìnmǔ or 舅妈 jiùmā mother’s brother’s wife; 妗子 jìnzi wife of one’s mother’s brother or wife of one’s wife’s brother; 婶娘 shěnniáng or 姨妈 yímā (married) sister of mother. As for ‘uncles’, 姨夫/父 yífu denotes the husband of one’s maternal aunt. back

24 Further ‘aunts’ on one’s father’s side are: 伯母 bómǔ, 大娘 dàniáng, or 大妈 dàmā ‘father’s elder brother’s wife’; the latter two can be used as terms of address; 婶 [婶] shěn (shěn), 婶子hěnzi or 婶母 shěnmǔ ‘father’s younger brother’s wife’. As for male relatives, 姑夫/父 gūfu or 姑丈 gūzhàng are used to denote the husband of one’s father’s sister. back

25 Gái ,female’ and trai ,male’ are used when referring to a third person. back

26 While the eldest son is: con trai trưởng, the eldest daughter is con gái trưởng. back

27 Data: Personal communication by Truong Thu Nhan. back

28 Data: Personal communication by Bahargül Hamut. When used in order to address someone, qīz and oğul must be used with the possessive suffix of the 1. person (qīzim, oğulum); when used in order to refer to the third person, no possessive marking is used. The same holds true for uka (‘younger brother/sister’). back

29 Some information on this development can be found in Perović (2000) . back