How to cite

Abstract

This paper aims to trace the pre-Islamic Zoroastrian concept of “royal divine glory” (farr) through its visual translations within the Iranian manuscript cultures in the Safavid period, specifically in the illustrations of the Shahnama-yi Shahi in the 16th century. Reviewing the longue durée idea of Iranian kingship perceived within the Safavid royal ideology in the reigns of the first two monarchs, we delve into the Shahnama paintings to see the artists’ assets for showing the divinity and dignity of Iranian kings and how they managed to mark a difference between the profane and Shiite iconographies. We took as case studies nine illustrations of Zahhak’s story, the most tyrannical legendary King in Shah Tahmasp’s Shahnama. Indeed, to analyse the artistic manifestations of the Royal farr, we examined the scenes where the “true” king is literally absent.

Keywords

Farr, Shah Tahmasp Shahnama, Zoroastrianism, Natural Elements, Plane Tree, Cypress

This article was received on 30 July 2022 and published on 9 October 2023 as part of Manazir Journal vol. 5 (2023): “The Idea of the Just Ruler in Persianate Art and Material Culture” edited by Negar Habibi.

Introduction

In Zoroastrianism, the ancient Iranian religion, the concept of farr(ah) (lit. “glory, (good) fortune”),1 particularly its specific form xwarrah ī kayān/farrah ī kayān (“royal auspiciousness/glory”),2 presents among other things the divine recognition that gives dignity to a king and makes him legitimate to reign over the people and the world (Farridnejad, Die Sprache der Bilder 340-347). According to the Avesta (Yt. 19), royal farr is reserved only for a certain circle of gods and humans, namely Ahura Mazdā (the supreme god of the Zoroastrian pantheon), other divine beings (e.g. the frawahrs3 and the Yazatas), the Soshyans (the eschatological redeemers), the prophet Zarathustra as well as the mythical kings of the Kayanid dynasty (Farridnejad, Die Sprache der Bilder 341; Humbach and Ichaporia, 30-57; Hintze 22). It is clear from this division that the bestowal of the “royal glory” (farrah ī kayān) was of special significance as a symbolic act for the political as well as religious Sasanian (224-651) kingship ideology during late antiquity (Farridnejad, Die Sprache der Bilder 341).

One of the last important literary and ideological treatments of the concept of the farrah ī kayān was developed under the Sasanians, as it is stated in the Kārnāmag ī Ardaxšīr ī Pābagān (“Book of the Deeds of Ardashir, Son of Pabag”), a Middle Persian prose text that narrates the life story of Ardashir I (r. 224–239/40), his ascent to the throne, as well as the battle against the last king of the Parthian Empire, Ardawan IV (216–224); a battle which led to Ardashir’s victory and the founding of the Sasanian Empire in CE 224. The visual “translation” of “royal farr” is also attested within Sasanian royal art, most specifically in the monumental reliefs, which date mainly to the 3rd and 4th centuries. The so-called Sasanian “investiture scenes” were one of the most popular themes of the early Sasanian reliefs, which generally show the kings receiving the symbol of the farrah ī kayān from the gods as a sign of legitimation and divine confirmation (Farridnejad, Die Sprache der Bilder 332-333).4 These themes remained popular in Iran until the 19th century.5

Being the official state religion of the last great Persian Empire before the advent of Islam, Zoroastrianism has survived after the fall of the Sasanian Empire as a minority religion with great cultural and religious impacts on Islamicate Iran as well as the Persianate world. Among the fundamental ideas of both religious and cultural importance, Ferdowsi’s Shahnama (Book of Kings), which stands on an older tradition of the previous Shahnama and the Sasanian Khwadāynāmags, was an important source for preserving and transferring the pre-Islamic mythological, cultural, and religious motives of the older Zoroastrian tradition, including farrah ī kayān. For instance, the myth of Jamshid in the Shahnama,6 delivers the central myth, which reflects the character and function of farr. Jamshid is privileged and legitimized by his divine farr and rules the world, until he loses it through sinful commitments. Indeed, farr is not everlasting and can also be lost. Furthermore, not all the kings have this divine privilege; some, like Jamshid, lost it by their arrogance and vanity, and some, like Zahhak, never had any at all.

In Ferdowsi’s Shahnama, farr appears as a light radiating from the King’s face. However, in Persian-Islamic artistic tradition, enlightened faces belong to the Islamic saints. From the 16th century onward, particularly, the Prophet Muhammad’s and Shi’i imams’ faces were covered with a luminous veil or fire flame showing their holiness and divinity. The same period coincided with the emergence of the Safavid dynasty (1501-1733) and the production of one of the noblest and most majestic illustrated Shahnama in Iranian history.

Created for the second Safavid king, Shah Tahmasp (r. 1524-1576), the royal 16th-century Shahnama is one of the finest manuscripts produced in the Islamicate world. Although indebted to the technical and artistic achievements of the previous periods, the visual experience of Shah Tahmasp’s Shahnama generated a new dialogue between different visual forms, people, and natural elements. The manuscript thus provides the most ideal artistic experience seen in Persianate manuscript paintings, which continued until the modern era (Welch; Hillenbrand, “The Iconography of the Shah-Nama-yi Shahi”; Canby). Since the visual manifestation of farr was already used within Islamic ideas, one may wonder how it has been shown in the Shahnama’s profane illustrations. Indeed, one of the very first illustrations of Shah Tahmasp’s Shahnama, on the praise of the Prophet Muhammad and Ahl al-bayt (the Prophet’s sacred family), portrays them with veiled faces with golden flames surrounding their heads (fol.18v).7 What were the artist’s methods used to represent the secular idea of farr, which was already engaged and employed as a religious concept?

In looking for an answer, we decided to search for the visual manifestation of the very concept of “divine glory” by specifically observing its “absence”. To find the idea of kingship perceived within the Safavid royal ideology, we examine the paintings in which the true and legitimate King is absent. We then compare the outcome with other illustrations of Shah Tahmasp’s Shahnama and other 16th and 17th- centuries illustrations. Doing so will help us understand how the idea of Iranian kingship and its manifestations are precisely “narrated” in the pictures of the Just Ruler and in his absence. Reviewing the scenes related to Zahhak’s reign, the most tyrannical legendary king ruling in Iran, and its nine illustrations in Shah Tahmasp’s Shahnama seems to be an appropriate starting point. Zahhak’s myth demonstrates, par excellence, the reign of misery and darkness in the absence of a legitimate Iranian king. It symbolized an age marked by sorcery and the dark magic of demons and tyrants in the absence of divine farr, which caused long periods of sorrow and misery.

Zahhak’s Story: A Synopsis

A detailed description of the thousand years of reign of terror of the serpent king Dahāg8as well as his demonic genealogy is preserved within the Zoroastrian Middle Persian (Pahlavi) texts, among others in Dēnkard (9.21.12-16) and Bundahišn (31.6). In the Shahnama, Zahhak (an Arabicized form of MP. Dahāg) is also portrayed as a demonic and cruel non-Iranian ruler of Iran.

The story of Zahhak begins during the reign of Jamshid, a legendary divinely glorified Iranian king much appreciated in the Shahnama for granting peace, generating justice and prosperity in the world, as well as creating artifacts and handicrafts. Near the end of his 700-year-reign, proud of his long-life achievements, he began considering himself not only the absolute ruler of the world but its creator. His decline then started as his farr was withdrawn.

Jamshid lost his wisdom and good fortune, and his reign fell in chaos. Meanwhile, in the Arab lands, located on the western border of Iranian territory, lived a young but diabolic prince named Zahhak, who began his reign by murdering his noble father under the auspices of Ahriman (“demon,” God’s adversary in the Zoroastrian tradition). At the beginning of his reign, Ahriman reappeared again and kissed Zahhak’s shoulders, where two diabolic and fierce serpents appeared and to whom young human brains soon became the daily feed. Zahhak also forcibly married Jamshid’s two beautiful daughters (or sisters) after defeating and killing him. Ruling with murder and injustice for one thousand years, Zahhak one night had a nightmare predicting the birth of a new king gifted by the lost divine farr, who would put an end to Zahhak’s tyranny and life. The newborn king’s name was Fereydun9, a descendant of Jamshid. With the help of the heroic rebel Kava, the blacksmith, Fereydun was able to wrest the kingdom from Zahhak and release the Iranian land from his tyranny. According to the legend, Zahhak is still chained in Mount Damavand, until the end of time, when he will finally be killed.

Zahhak’s Illustrations in the Shahnama of Shah Tahmasp

The Death of Shah Mardas10

The Shah Tahmasp Shahnama illustrates this story as occurring in a very green garden, just as it is mentioned in the text: “King Mardas owned a fine orchard, and he would go there in the dawn’s darkness, to wash his head and body, and to pray.”(54)11

A green garden with cypress and trees in flower (probably almond and peach) are shown here; a spring-blessed garden attesting to the King’s good fortune. He is, however, now lying dead in a pit dug by Eblis (the Quʾranic designation of the Devil), who filled the pit in with soil before going on his way. Two lines of the text on four colons effectively show the soil covering the deep pit. In a red costume, the King’s servant is biting his finger as a sign of wonder and sorrow; he leads the eyes to two cypresses in the garden, who alongside the curving branches of the three blossom trees point to the real culprit: “the evil offspring son who broke faith with his noble king father” (54) and became complicit in his murder. This breaking faith from the father is shown very well in the architectural plan of the King’s palace: Zahhak is located in a tidy balcony outside the main building, whereas a woman belonging to the king’s household is shown inside. The dark blue sky may show the time of the day, the dawn’s darkness where the King Mardas used to pray; it may also serve as a presage, forewarning the reader of the coming dark days.

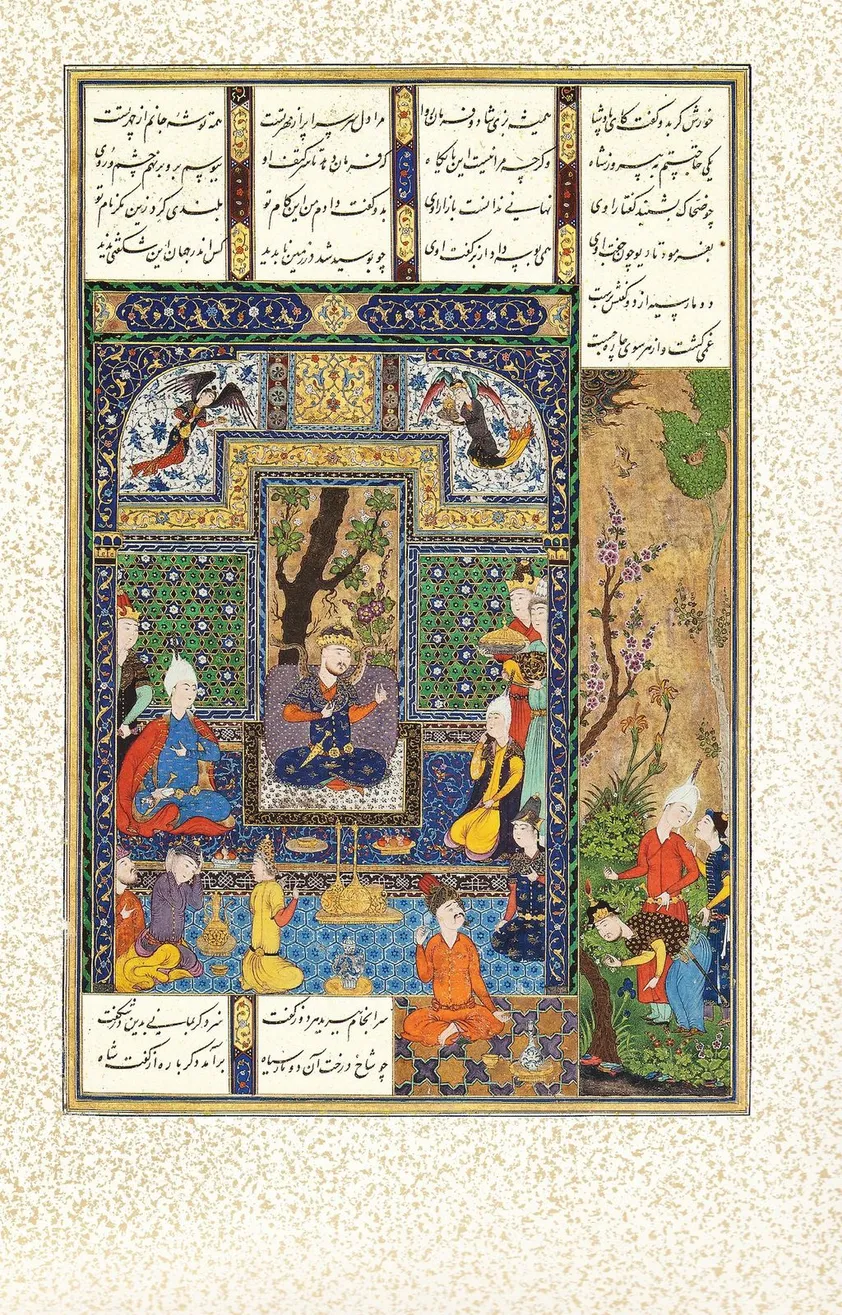

The Snakes Appear on Zahhak’s Shoulders12

Zahhak is illustrated in the center of the image, framed in a closed and tidy architectural setting (fig. 1). Leaning on a cushion, the two fierce snakes jump out of his shoulders, threatening the men gathering around the young king. The latter are probably the doctors giving their opinions to the miserable king who looks distressed by his anguished brows and eyes, and who is gesturing towards the snakes with both hands. Whereas all the men in the palace show their surprise and bewilderment by the hands’ gestures, there is one young man, in the bottom left corner, grabbing his head with two hands; he is recalling the following verses of the story, where the King orders sacrificing humans for taking their brains for his snakes.

The scene is undoubtedly very colorful, and the environment seems, at first glance, to be joyful. Carpets and different types of tiles lavishly decorate the interior of the palace and there are two magnificent mural paintings on the niches, showing two angels bringing wine and food in the golden vessels. These angels, the divine messengers, are certainly derived from the pre-Islamic reliefs, and have been employed several times in Persian-Islamic painting; they are specially seen in illustrations of the Prophet Muhammad from the 13th to the late 14th centuries, saluting him, bringing the divine light, perfume, and glory to the God’s latest élu.13

They are, however, blocked and stagnated in their frames in this painting with no access to the seated King; the blue and white tiles and the golden window arch barricade the angels’ descent. They look somewhat frozen, recalling the “idea” of the Divine who is no longer existent.

The window behind Zahhak shows a barely bloomed tree and a purple hollyhock. The window frame, however, cuts the tree whose bottom branches, those near Zahhak, are dried and dead. A look at the flower shows a tragic end as the snake in Zahhak’s left shoulder is biting and cutting it savagely. The dark stormy clouds also announce the woeful fate in the golden outdoor sky.

As is the case for the lavishly decorated pavilion, nature in the garden seems joyful. We are still in the reign of the Great Jamshid, just like the tree shown in the backside of the painting; even if Jamshid is now disgraced and his farr is removed, the world enjoys the last moments of peace and prosperity. However, Zahhak would find the hidden Jamshid and cut him in half, just as the window’s frame behind him cuts the tree.

Zahhak Receives the Daughters/Sisters of Jamshid14

The dragon head shape of the throne’s feet and the tiger heads under the balcony on the right side of the palace may recall Zahhak himself described as a serpentine/Azhdaha/dragon creature in the Arab Lands (56) and his reign which lasted:

a thousand years, and from end to end the world was his to command. The wise concealed themselves and their deeds, and devils achieved their heart’s desire. Virtue was despised and magic applauded, justice hid itself away while evil flourished; demons rejoiced in their wickedness, while goodness was spoken of only in secret. (58)

Overall, there are many convoluted arabesques on the decorative program around Zahhak; on the curtains, the throne, the white cushion, the tiles, and even on the princess’s tunic, as if the arabesques are tying up her arms and imprisoning her. Just like the snakes are turned toward the King and encircling him, so are the decorations in the center of the image. The large arabesque in the lower part of the throne also retreats from the snakes’ curves. Outside the center of the image, the decorations are more geometric and less invading.

The large window is removed, and heavy curtains replace the descending angels seen in the mural paintings; the divine messengers are now literally occulted. Instead, a fine tableau of a golden jar and flowers on a white background is framed on the left wall. A nature morte, which may recall the symbolic idea of glorious nature, is now dead and firmly framed.

The garden on the right side of the page is essentially unchanged from the previous scene; the same trees, maybe as the souvenir of Jamshid’s reign, are recalling other heirs, his daughters. It even seems that the large chenār (plane tree) behind the palace walls with two main branches alludes to Jamshid and his two daughters/sisters. As we see below, representing a “true” king and/or the “idea of Iranian kingship” by a tree and their descendants by flowers or the tree’s branches is reiterated several times in other Safavid illustrated books and paintings.

Zahhak’s Nightmare15

Zahhak, who so far was covered with gold and had the most prestigious and central place in the illustrations, is now retired in the second plan on the upper left side, as small and weak as other characters in the composition. He seems undersized in his high walled chamber. Zahhak looks even more feeble, old with a white beard, and cut off by the balcony’s golden railing. This golden rectangular is the only majestic part that depicts Zahhak as king; even Zahhak’s snakes seem less frightening. One may also note that the two green supports that hold the balcony outside the building are no longer decorated by a tiger or dragon’s head.

The composition is filled with human figures of the same size as Zahhak, semi-dazed and semi-shocked by the King’s cry. Zahhak is surrounded by his female household and one of Jamshid’s daughters/sisters, Arnavaz. An ornate closed door behind him seems to block access to the King’s chamber, suggesting a complex issue with no apparent solution.

The natural landscape still generates symbolic ideas, facilitating the story’s reading and interpretation. A golden crescent moon shines in the dark blue sky in the middle of spiral white clouds. This narrow section of nature in the middle of the scene with a cypress and a blossom tree seems to belong to another space and time than that of the garden outside of the palace on the right side of the illustration. The contrast of pinkish flowers on the dark blue sky illuminates this small part of the painting, whereas the trees in the garden, barely bloomed, seem somber and less magnificent.

In this landscape, one finds the true meaning of Zahhak’s nightmare explained in the accompanying verses: “soon, a new hero will be born; he looks like a tree as high and green as a cypress heading up to the moon and blossoms like the fruit tree in the Spring” (61). Fereydun, a new king, will end Zahhak’s tyranny, just as the glorified trees spring out in the middle of Zahhak’s palace.

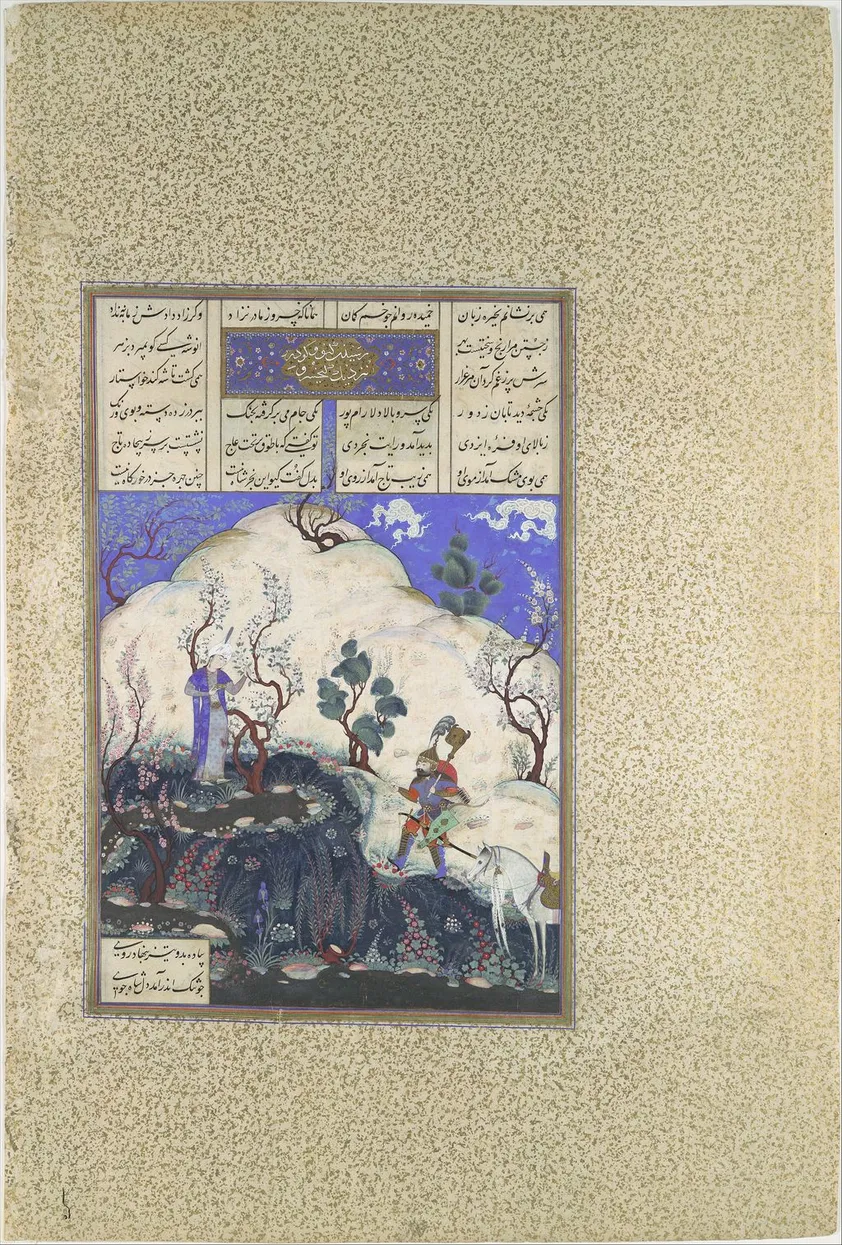

Zahhak’s Fate is Told16

Zahhak’s palace, showing the throne room, consists of a high-walled building that surpasses the upper framework of the text (fig. 2). According to Ferdowsi, Zahhak’s palace had walls “shone like the planet Jupiter in the heavens and were so high that they seemed to reach for the stars” (68). A high iwan (a large vaulted hall, closed on three sides and open to a court on the fourth) decorated by blue and polychrome tiles shows a large barely decorated room with white walls. At the center of the piece stands a huge golden throne whose gray-bearded beholder is now fainted, bare head with his feet under the throne.

Narrower than in the previous scenes, the building only occupies half of the composition; thus, more ground is given to nature. A mostly devoid hilly landscape shows only two parterres, and a dark blue sky occupying the higher part of the scene sits harmoniously with the building’s blue decoration. Nevertheless, a delicate blossom tree is rising behind the barren hill, its pinkish flowers shining in the sky like the stars, recalling the pinkish flower in the last scene. This tree is so high that it actually reaches the spiral-shaped white clouds. Two cypresses and another flowering tree complete the outside scene, as if announcing the arrival of the other tree behind the hill.

Zahhak Slays the Sacred Cow Barmaya17

The golden and feathered-crowned Zahhak, the King leading the carnage, is mounted on a light grey horse, slaying Barmaya, the sacred cow provided milk to Fereydun for four years. Zahhak’s men are killing other animals. In the upper left part of the painting is a building where Fereydun once lived, now abandoned, as Fereydun left to settle down on Damavand Mountain. The open doors, windows, and empty balcony perfectly show the uninhabited house. Zahhak will burn and raze it after terminating the massacre of the animals. Nonetheless, the building’s garden looks vibrant, green, and joyful. There are three cypress trees located behind the tall plane tree, only one of which is ornate with white almond blossoms.

The idea of a tree as a symbol of the true king is again emphasized in this episode. Zahhak (shown without the snakes) occupies the center of the page, framed by a barren desert hill. However, his size and colors are not on par with the tall green chenār, the oriental plane tree raised at the top of the hill just above him. In contrast to the area around Zahhak, there are several flowers and greenery around the silver river (now oxide), which flows from a spring at the foot of the tree.

All these elements narrate the following chapters of the story; the golden sky announces the glorious days which will be brought by Fereydun and his “Jamshid’s imperial farr”, represented here by the plane tree. The three cypresses announce in turn the descendants of Fereydun, his three famous sons: Iraj, Salm and Tour. As Ferdowsi recounts, Salm and Tour become the kings of other lands in Turan, and murder their younger brother Iraj, the King of Iran, here shown by the blossom cypress.

Thus, nature and its elements, mainly trees, seem to substitute the hallowed radiant-faced king(s), promising the “idea” of a true king. Fereydun, a descendent of Jamshid, is figuratively absent in this painting, as was Jamshid himself absent in previous pages, but a tall green tree symbolically represents them both. Nature, furthermore, continues to anticipate the story.

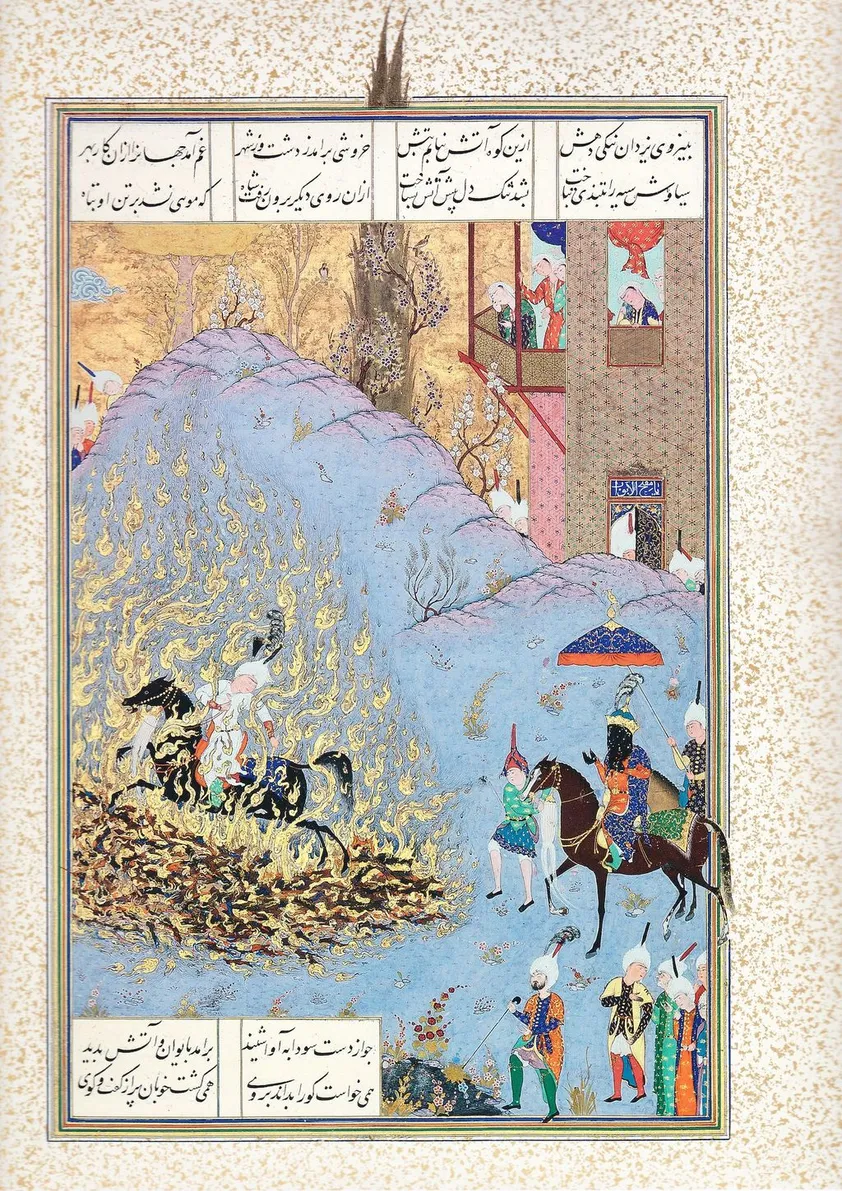

Kava Tears up the Letter18

Zahhak, with a white beard, sits on his golden throne, his black snakes fierce and tormenting him. Zahhak looks at Kava, standing in a blue tunic with his famous blacksmith leather, tearing up the testament drafted by Zahhak, which attested to his justice and kindheartedness (fig. 3).

As soon as he leaves Zahhak’s palace, Kava gathers men around him seeking Fereydun, and the decline of Zahhak takes the final turn. Nature in its magnificence, with natural or supernatural elements, announces this near victory. This scene presents the most prosperous and joyful nature among the illustrations of Zahhak’s story. The hill in the garden appears as a most luscious symbol of Spring where the blossoms and many other trees are grown; tufts of grass and flowers covering the green hill. Not only is the sky golden with blue clouds, but the latter are pointing to three descending angels. They are no more the frozen images fixed and hung on the walls, but active and bringing farr and fortune.

This painting’s composition recalls another episode from Fereydun’s reign.19 In both paintings, the kings sit on a golden throne surrounded by their men, with a garden on the right side of the page. Both kings’ thrones are under lavishly decorated tents, but where the demons surround Zahhak’s upper parts of the tents, Fereydun’s tent is attended by angels. The angels are indeed shown in both paintings. In Fereydun’s, they are situated in the interior and the main part of the illustration, floating in the air and pouring light to Fereydun. However, in Zahhak’s scene, the angels are speaking with an observer behind the hill; they are also situated in the margin of the painting and not in its interior, delimited by the sections of text. Whereas in Fereydun’s scene, the angels are the active actors of the scene, in the Zahhak’s, they have a secondary and not yet performed role.

Fereydun Strikes Zahhak with the Ox-headed Mace20

Here, one last shot of Zahhak’s palace located in Jerusalem is presented, inhabited now by Fereydun. He removed the evil charms and witchcraft from the palace, and liberated Jamshid’s beautiful daughters/sisters from Zahhak’s dark magic. They both are shown sitting on the throne as they accompany, day and night, the new King of Iran.

The throne chamber is the same as in “Zahhak’s fate is told” (fig. 2); both buildings have a large and high iwan decorated with blue and polychrome tiles, a white wall behind the throne, and silver windows on each side of the walls. However, the wall behind the throne in this current scene shows a slight alteration in its decoration. Whereas the walls behind the throne are entirely white in the previous scene, here, the scenes of girift-u-gir (lit. caught and stuck) between the lions and gazelles are painted in blue on the walls. Thus, even if nature is somehow tangibly absent, it virtually exists as an image on the walls, recalling the real fight happening on the bottom side of the painting where Fereydun strikes Zahhak with his ox-headed mace.

Moreover, the Angel Soroush21 is now literally accompanying Fereydun—as also mentioned in the text—descending vertically from the sky. Just above his head, as if he recites the divine words, is written in a masterful Naskh inscription on the top of the arc of iwan: May all your efforts be at your pleasing, God of the universe protects/bless you (bi kam-i tu bad hama kar-i tu, khudavand-i giti negahdar-i tu).

The Death of Zahhak22

Zahhak, in blue underwear and red pantaloons, is enchained in a cave on top of the mountain. The mountain is so high that it reaches the stormy clouds; several dragon heads are hidden in these clouds, as if they were to soon devour Zahhak. He is simultaneously threatened not only by these dragon-shaped clouds but also by the mountain’s rocks encircling and pointing at him; it is as if the cave will soon be closed by the circular movement of the stones and rocks. Zahhak is going to be devoured by nature.

The Tree as a Generative Idea of the “Idea of Kingship”: Towards a New Visual Trope

Among the nine illustrations reviewed here, eight contain natural scenes like gardens or wild and non-constructed landscapes. The main actors in both categories are the plane trees or cypresses embraced with blossom, almond, or peach trees. A look at 258 illustrations of Shah Tahmasp’s Shahnama also champions trees as a primordial element in the decorative program of the manuscript.23 They arise in the royal gardens or the middle of battle scenes. Not only do they assist the narration and predict the future, they also seem to be the Kings’ hallmarks. They emerge by the true king and, in some cases, accompany the heroes such as Zal (fols. 73v24 or 104r25 to name a few examples). Zal is, indeed, an interesting case; in Ferdowsi’s Shahnama, Zal is calling farr, fortune and grace, the wings of Simurgh—a legendary bird with supernatural powers.26 The bird offered him its feathers by saying: “be always in the shadow of my fortune and grace (saya-yi farr-i man)” (Schmidt). Simurgh physically accompanies Zal in three folios, mainly at the beginning of Zal’s story when he lives in the mountain with her. Nevertheless, in several other episodes, a tree, mainly a high cypress, sits right behind the hero, who becomes, in turn, the King of Zabulistan. One may also note that Simurgh is closely related to the concept of trees, as reported in the Zoroastrian texts. He/she is housed on a tree which “has good and potent medicine, is called all-healing, and the seeds of all plants are deposited on it. When the bird rises, a thousand shoots grow from the tree, and when he (or she) alights, he breaks a thousand shoots and lets the seeds drop from them” (Schmidt).

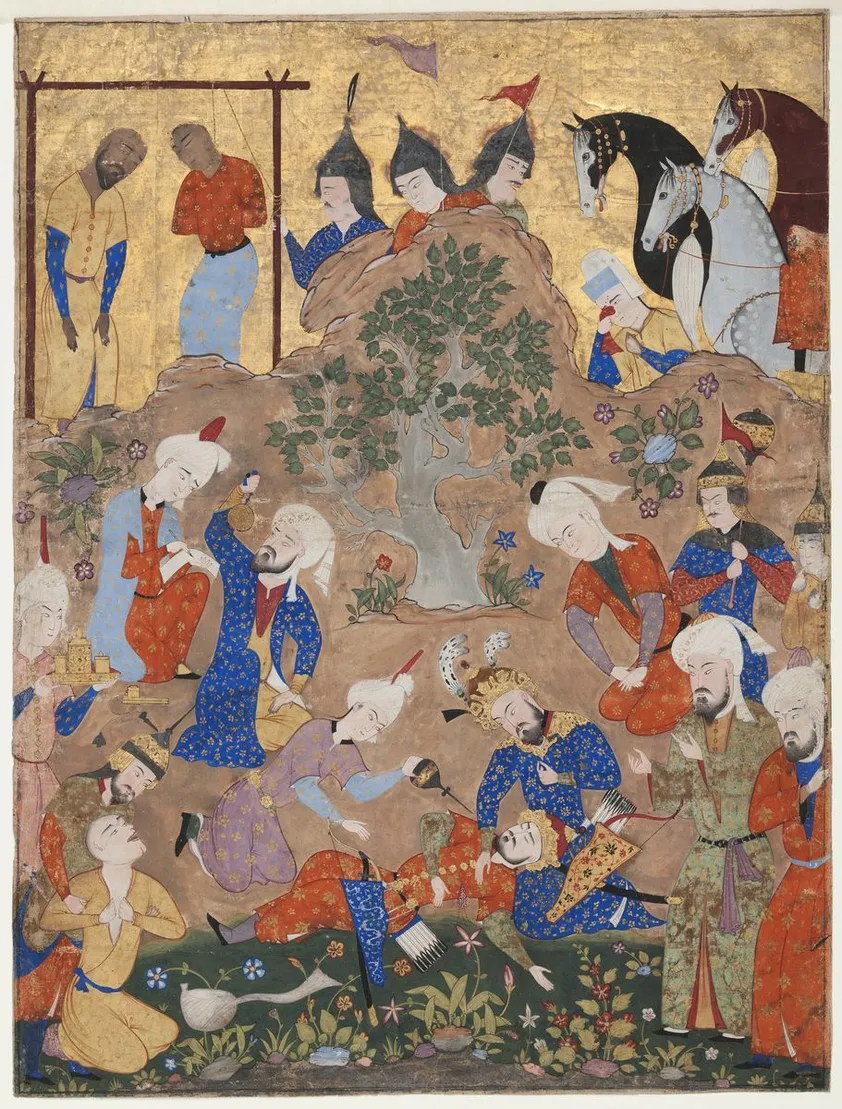

In Shah Tahmasp’s Shahnama, trees occupy a considerable space in the royal scenes where the legendary Iranian kings are represented; in “Kay Khusraw is discovered by Guiv,”27 for instance, the area surrounding the future king of Iran, son of Siavush, is a greenery scene full of flowers (fig. 4). The prince’s realm, painted in blue and green, is distinguished remarkably from the barren white hillock all around. This microclimate around the King shows a flamboyant nature with hollyhocks, iris, and blossom trees. The Prince is standing on the top of this vegetation by a water source; he holds a wine goblet or grail in one hand and, with the other, one of the branches of an interlaced tall blossom tree standing by him. In the Perso-Islamic illustration tradition, several scenes show seated kings holding a grail in one hand and a scarf or handkerchief in the other.

One may read the tree’s presence and its physical interaction with Kay Khusraw in the same manner, especially by taking into account Ferdowsi’s words on the young prince: “a handsome young man, cypress-tall [...] God-given farr was apparent in his stature, and wisdom in his mien.” (370)

Interestingly enough, Kay Kavus, the prince’s grandfather, one of the most avid and impulsive kings in the Shahnama, not admired by either people or heroes, is seldom shown near any trees. Amongst twelve episodes concerning Kay Kavus, only five scenes represent trees, but in most of them, the King is accompanied by a legendary hero or his noble heirs, such as Siavush or Kay Khusraw. In “Siavush passing through the fire”28, the infamous king is shown with a dark veil covering his face and a black glove covering his hands on the right side of the painting (fig. 5). In contrast, a golden plane tree is on the upper side of the image, in line with the young prince in the middle of the golden fire.

The paintings in Shah Tahmasp’s Shahnama demonstrate a hegemonic and inclusive vocabulary regarding the divinity and glory of the legendary kings. Gardens or landscapes sublimely rich in flowers, rivers and trees, and specially the precise and deliberate position of trees are among the ways the legendary and mythical kings, those endowed by the divine glory and farr, are represented and distinguished from ordinary people or rival kings.29

Trees, whether the planes or cypresses interlaced by blossom trees, accompany the kings or princes in several other Safavid book illustrations and single sheet album paintings. In “Sultan Sanjar and the Old Woman” in Shah Tahamsp’s Khamsa of Nizami (Quintet)—produced in Tabriz a bit later than Shahnama between 1539-154330—a giant plane tree occupies the upper part of the painting, standing in the same vertical line as the Sultan. The tree is, however, surrounded by several rocks, as if they will soon devour the tree (similar to Zahhak’s death on the mountain). Sun is brightening in the upper left side of the painting, but several clouds are covering it. The tree reveals the ruler, but the rocks and clouds predict the unfortunate end of Sultan Sanjar’s reign. Although conquering Khurasan, his reign ends soon as he is not a just ruler.

The plane tree also occupies a central place in a folio of Shah Tahmasp’s Falnama (the Book of Omens), produced in Qazvin during 1550-1560 (fig. 6).31 The painting illustrates the death of Dara, the last Achaemenid king, and the shift of power to Alexander the Great. Whereas the protagonists occupy the lower part of the painting and a golden sky the upper part, a robust plane tree sits in the center of the page. Two flowers rise on each side of the tree, one in blue and the other in red, recalling the tunics of Alexander and Dara, respectively. According to Iranian literature and mythology, Alexander was not a foreign king, but one with “Iranian blood” from his father as he was Dara’s half-brother. One may then wonder if the sturdy tree, with the flowers near its base, represent the “idea of Iranian kingship” and the power transfer between two true kings.

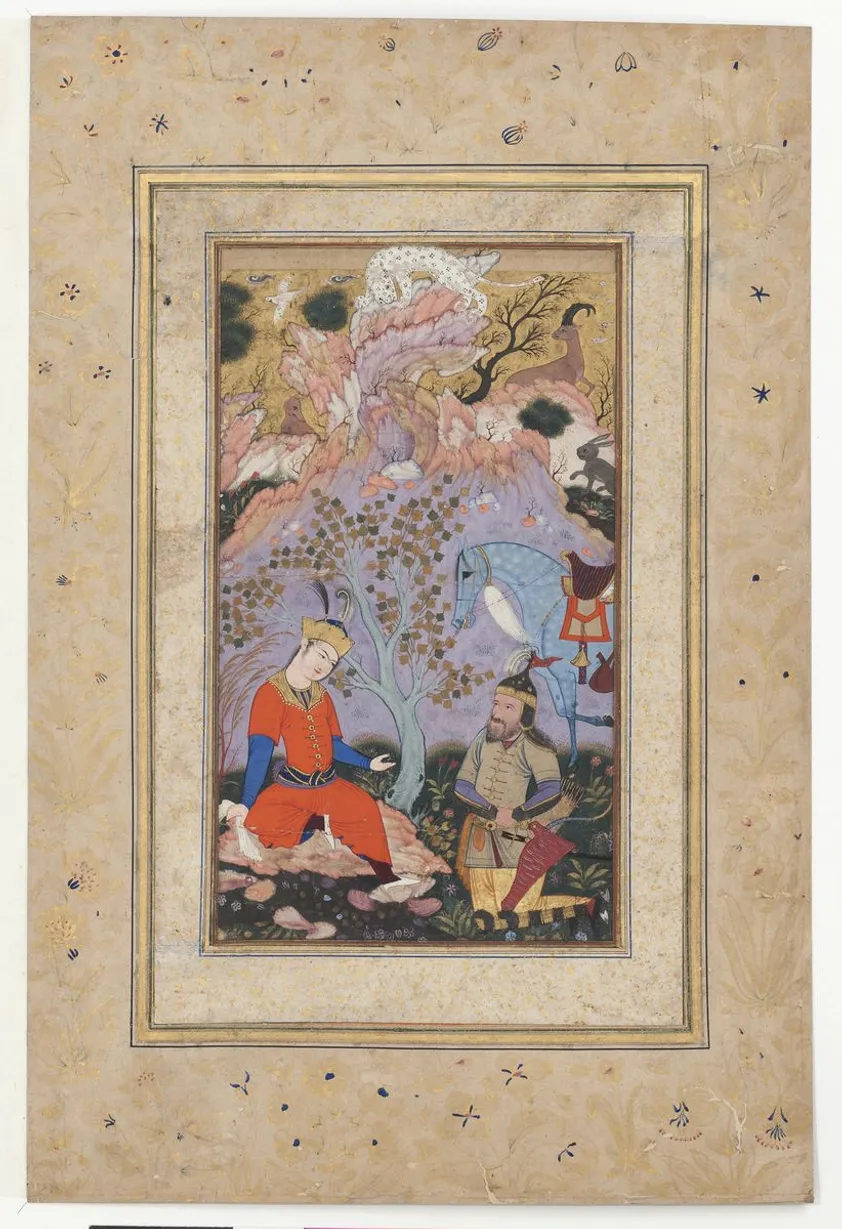

Trees as a kingly symbol also appear in several textless album pages; a mid-16th-century page in Qazvin style now in Cleveland Art Museum effectively shows Shah Tahmasp kneeling pensively on a carpet under a willow on the banks of a stream;32 it may come from an Indian interpretation of the same scene now in the V&A.33 Another 17th-century page in Geneva’s collection represents probably “Kay Khusraw is Discovered by Giv” (Robinson 140) (fig. 7). Produced in Isfahan in the manner of Riza-yi ʿAbbasi, one of the figures with armor, helmet and bow seems to be a warrior, probably Giv, whereas the other figure, coiffed with a golden crown, may be the Iranian Prince. His manner of sitting with one leg bent, holding a sash in one hand and a crown on the head reveal undoubtedly his high rank and kingly position. A curved tree shapes an arc around the king and presumably attests to his blessed rank.

Tree as a hallmark of the king systematically presented in the early Safavid paintings may be seen, in a more sporadic way, in other periods before the advent of Safavids. For instance, a copy of Khamsa dated to 1406-1410 represents Khusraw at Shirin’s castle.34 Like Sultan Sanjar, a tall plane tree—perfectly harmonious with Khusraw’s green cap—arises on the same line in the page’s upper part. A folio of a 15th-century Khamsa also shows Alexander leaning on a tree while discussing with the Seven Sages.35

As a symbol of the “idea of kingship”, trees date far beyond the Islamic era in Iran. There is, indeed, a significant reference to the close connection between the cypress tree and the notion of divine kingship as the legitimate patron of the religion in the Zoroastrian tradition. There are a number of celebrated cypresses, which were also remembered by later Muslim authors in both Persian and Arabic sources (Farridnejad, “Zoroastrian Pilgrimage Songs” 131-132). The first and most important of the famous cypresses is that of Kashmar in Balkh-i Bami (in the district of Tarshiz in Khurasan). This cypress plays a significant symbolic role in the narrative of the foundation of the Zoroastrian religion, commemorating the conversion of King Gushtasp36 by Zarathustra. The narrative is composed by Abu Mansur Ahmad Daqiqi (d. c. 976) in Shahnama, according to which, the prophet Zarathustra brings a miraculous cypress tree from Paradise which was planted either by Zarathustra himself or by the newly converted King Goshtasp at the gate of the Fire Temple of Kashmar. The tree bears an inscription carved in the trunk commemorating the conversion of the King, who embraced the “good religion” (i.e. Zoroastrianism) and became its patron. This tree became a famous place of pilgrimage, remembered well into the 10th century and beyond (Dahlén 132–33; Farridnejad, “Zoroastrian Pilgrimage Songs” 131-132).

Lionel Bier suggests that “early Muslim rulers looked to their Sassanian predecessors for means by which to express a concept of kingship in architectural as well as ceremonial terms” (cited in Babaie 180). A review of the early Safavid paintings suggest that the Safavid kings also looked at Iran’s pre-Islamic idea of kingship. The Safavid written sources likewise allude to this fact. Shah Ismaʿil (r. 1501-24), the first political ruler of the dynasty, connected the legacy of his dynasty to the pre-Islamic Iranian kings “by forging a (fictitious) genealogy linking the last Sassanian king, Yazdegerd III, to the Shi’i third Imam, Hussein, by way of a presumed marriage with the King’s daughter, Shahrbanu” (Matthee, “The Idea of Iran” 85). Shah Ismaʿil, indeed, linked himself to pre-Islamic kings and heroes, such as Fereydun and Jamshid, and gave his children Persian names from the Shahnama, such as Sam Mirza, Bahram Miraz or Farangis Khanum (Tarikh-i Safaviyan 7, 32).37 In some Safavid texts, we read that farrah-i izadi radiates Shah Ismaʿil’s face, confirming his celestial rank, making his enemies—mainly the rival local governors of different Iranian provinces—attest to his divine kingship (ʿAlam-ara-yi Safavi 400, 487).38 We also read that Ismaʿil is the chosen king, who is throned with the divine affirmation to become the Khalifat fi al-arz (King on earth) (Qazvini 7). Shah Tahmasp also continued to be venerated as a god-like figure.39

Nevertheless the Safavid idea of kingship, even after the death of the dynasty’s founder, was animated and legitimized by the correlation of faith and dynasty. Inventing new religious-political policies and introducing the Twelver Imam Shi’i to Iran as the official state religion, the Safavids also saw themselves as the inheritors of the legacy of the Shi’i imams. Shah Ismaʿil audaciously asserted that he was synonymous with the pre-existent Mystery of God, the Light of Muhammad, as well as “engendered from the same metaphysical fabric as ʿAli, the Prince of the Faithful (Amir al-Muʿmenin)” (Gruber 55; Csirkes 371). He, indeed, claimed to be of divine nature in his Divan (in Turkish), when he says “velī kim ism ile Şāh İsma‘īldür Khaṭāyīdür ‘Alīning çākeridür : The saint/But he whose name is Shah Ismail, is Khatāyī, slave to ʿAlī” (Csirkes 374-375).

As Twelver Shi’ism became the official faith, the King was the trustee of the divine, and his mandate was to be the enforcer of God’s will and the executive officer of the Twelfth Imam. However, as Rudi Matthee points out, “Safavid Iran was salvific in presentation but essentially a dynastic enterprise” (“The Idea of Iran” 95). Thus, “realm and faith were twinned, al-mulk va al-din tu’aman” as mentioned in Ahsan al-Tawarikh describing Shah Ismaʿil’s II (r. 1576-1577) governorship (Rumlu 623). The same source mentioned that “the endurance (istiqamat) of a kingdom is not achieved without the strength (istihkam) of the Shari’a rules […] God gives the kingdom to who celebrates and officializes the religion: ta’vil tu’aman nabud gheyr as an ki mulk, an ra dahad khuday ke din ra shuʿar kard.” 40(Rumlu 623)

In his study on Shah Ismail’s Divan (Book of Poetry), Ference Csirkes shows how the Safavid shahs relied on an impressively variegated range of legitimization, including, among others, “ʿAlid messianic rhetoric (to mobilize their zealot nomadic adherents); Turco-Mongol symbols and apocryphal legends (to accentuate martial traditions and a sense of loyalty to Steppe); legalistic and orthopraxis aspects of Twelver Shiite doctrine; ancient, pre-Islamic Iranian notions of divine kingship and statecraft” (389).

The Safavid political ideology makes, indeed, an apparent reference to the notion of pre-Islamic, precisely Sassanian’s, royal ideology, which is the close connection and correlation between the state and faith. This is reflected, among other places, in some Pahlavi texts such as the Kārnāmag ī Ardaxšīr ī Pābagān (KAP) and also The letter of Tansar (LoT from a lost original in Middle Persian). In KAP, we read: “Know the kingship and religion are twin brothers, no one of which can be maintained without the other; for religion is the foundation of kingship, and kingship is the guardian or religion. Kingship cannot subsist without its foundation, and religion cannot subsist without its guardian”. In LoT, one reads: “For church and state are born of the one womb, joined together and never be sundered” (Boyce 109; Gnoli 170).

We may ultimately remind that the middle-Persian term Iranshahr (land of Iran) was introduced by the Sassanians and was employed many times by Iranian Muslim viziers, princes, and kings. The Safavids also resuscitated the idea, as is seen in several 16th and 17th century chronicles and the non-official treaties such as Mukhtasar-i Mufid. Written by Muhammad Mufid Maustufi, this is one of the rare Safavid geographical works, which shows its author’s keen interest in Iranian dynasties and the formation of an Iranian identity both as an ancestral and Shi’i civilization (21).41 We may thus conclude that the Sassanian “Idea” of kingship remained palpable in the Safavid era, manifested in written and artistic sources.

Pictures from the Safavid period not only functioned as a visual intensification of the reading experience but also, as emphasized by Gruber, “carried within their iconographic makeup subtle message about a particular Safavid monarch’s nature or the specific religious system that he aspired to deploy and implement” (50); we may add to her statement that the early Safavid images also carried the longue durée idea of kingship that the monarchs sought to reveal: the portrait of a chosen divine king as the patron and guardian of religion and state. The ancestral Sassanian Zoroastrian concept of Tree has been used as a new visual trope for showing the King’s divinity and dignity.

Conclusion

Our study of the royal Shahnama concerns a period in Tabriz, the first Safavid capital, when Shah Tahmasp was not yet imbued in his newly-created entourage of “imported” orthodox Shi’i theologians. Though he did not follow his father’s messianic rule and undertook several significant religious and military reforms, Shah Tahmasp kept some of the ideas of Iranian kingship promoted by Shah Ismaʿil and patronized the production of the most glorious and magnificent copy of what modern historians call the “Iranian identity card”, Shahnama (Melville 3).

The folios in the Shahnama briefly reviewed here were produced before the King eventually declared repentance for his sins in 1556.42 Shah Tahmasp repented, indeed, for the “forbidden acts” such as drinking and smoking and later issued an Edict of Sincere Repentance in which he outlawed the secular arts throughout his lands. However, the longevity of the new visual paradigm and tropes created before this period is tangible in the artworks produced in later periods. Just as his heirs, especially Shah ʿAbbas I (r. 1587-1629) continued and perfected Tahmasp’s geopolitical reforms, the visual tropes, both in the religious and profane arts introduced by him, continued to be exercised throughout 17th-century Iran.

According to Gruber, representing Prophet Muhammad and Shi’i Imams with radiant faces, exposing their divine invisible light, and the accompaniment of angels, is one of the main themes employed in the illustrations commanded by the first two Safavid kings (“When Nubuvvat Encounters Valāyat”). The secular illustrations in the same period borrowed some of the Islamic divinity’s manifestations, especially the angels emitting light, to indicate the glorified chosen king. The artists, however, systematically employed other idioms, specifically trees, as hallmarks of a true and Just Ruler. Future research will hopefully elucidate different significations and symbolic meanings and narrations of trees in Iranian religious and historical literature. Moreover, our paper did not explore the degree to which the 16th-century Safavids were conscious of the pre-Islamic ruins by using their visual tropes in contemporary manuscript paintings.43 Instead, we pursued the perpetuated “idea” of kingship from the Sassanian period, where both notions of farr and tree were commonly used in the Idea of Iranian Kingship.

Nature and its elements have been used in Shahnama illustrations since the 14th century (See Hillenbrand, The Great Mongol Shahnama for instance). However, in the 16th-century royal Shahnama, they appear as a narrative assistant to facilitate the reading, anticipate the coming episodes, and eventually use the tree to signify the true king and his glorified divine farr.

Bibliography

ʿAlam ara-yi safavi, edited by Yadoallah Shokri, Bondyad wa farhang-i Iran, 1350/1971.

Allen, Lindsay and Moya Carey. “Eminences Grises: Emergent Antiquities in Seventeenth-Century Iran.” Afterlives of Ancient Rock-Cut Monuments in the Near East, edited by Jonathan Ben-Dov and Felipe Rojas, Culture and History of the Ancient Near East 123, Brill, 2021, pp. 272-344.

Babaie, Sussan and Talinn Grigor, editors. Persian Kingship and Architecture: Strategies of Power in Iran from the Achaemenids to the Pahlavis. I.B. Tauris, 2015.

Boyce, Mary. Textual Sources for the Study of Zoroastrianism. Manchester UP, 1984.

Canby, Sheila R., The Shahnama of Shah Tahmasp: The Persian Book of Kings. Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2011.

Csirkés, Ferenc. “A Messiah Untamed: Notes on the Philology of Shah Ismāʿīl’s Dīvān”. Iranian Studies, vol. 52, no. 3-4, 2019, pp. 339-395.

Davis, Dick, translator. Shahnameh: The Persian Book of Kings. Penguin Classics. Penguin Books, 2016.

Farridnejad, Shervin. “Zoroastrian Pilgrimage Songs and Ziyārat-Nāmes (Visitation Supplications). Zoroastrian Literature in New Persian II.” Zaraθuštrōtǝma. Zoroastrian and Iranian Studies in Honour of Philip G. Kreyenbroek, edited by Shervin Farridnejad, 2nd ed. Ancient Iranian Series 10, Brill, 2020, pp. 115-92.

---. Die Sprache der Bilder: Eine Studie zur ikonographischen Exegese der anthropomorphen Götterbilder im Zoroastrismus. Iranica 27. Harrassowitz, 2018.

Gnoli, Gherardo. The Idea of Iran: An Essay on Its Origin. Serie Orientale Roma 62, Istituto Italiano per il Medio (IsMEO), 1989.

Gruber, Christiane. “When Nubuvvat Encounters Valāyat: Safavid Paintings of the Prophet Muhammad’s Mi’rāj, c. 1500–50.” The Art and Material Culture of Iranian Shi’ism: Iconography and Religious Devotion in Shi’i Islam, edited by Pedram Khosronejad, Iran and the Persianate World, I.B. Tauris, 2012, pp. 46-74.

---. The Praiseworthy One: The Prophet Muhammad in Islamic Texts and Images. Indiana UP, 2018.

Hillenbrand, Robert. The Great Mongol Shahnama. Hali, 2022.

---. “The Iconography of the Shah-Nama-yi Shahi.”. In Safavid Persia: The History and Politics of an Islamic Society, edited by Charles Melville, Pembroke Persian Papers 4, I.B. Tauris, 1996, pp. 53-78.

Hintze, Almut. Der Zamyād-Yašt: Edition, Übersetzung, Kommentar. Beiträge zur Iranistik 15, Ludwig Reichert, 1994.

Humbach, Helmut and Pallan R. Ichaporia. Zamyād Yasht: Yasht 19 of the Younger Avesta. Text, Translation, Commentary. Harrassowitz, 1998.

Matthee, Rudi. “The Idea of Iran in the Safavid Period: Dynastic Pre-Eminence and Urban Pride.” Safavid Persia in the Age of Empires, edited by Charles Melville, I.B. Tauris, 2021, pp. 81-103. The Idea of Iran 10.

---. Persia in Crisis: Safavid Decline and the Fall of Isfahan. I. B. Tauris, 2012.

---. The Pursuit of Pleasure, Drugs and Stimulants in Iranian History, 1500-1900. Princeton UP, 2011.

Melville, Charles. “The Shahnameh in historical context.” Epic of the Persian Kings: the Art of Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh, edited by Barbara Brend and Charles Melville. I.B. Tauris, 2011.

Maustufi Bagqi, Muhammad-Mofid. Mukhtasar-i Mofid: Goqrafia-ye Iran-zamin dar ʿasr-e safavi, edited by Iraj Afshar and Mohammad-Reza aboui Mehrizi, Bonyad-e moqufut-e doktor mahmud-e afshar, 1390/2001.

Motaghedi, Kianoosh. “From the Chehel Sotun to the ‘Emarat-e Divani of Qom: The Evolution of Royal Wall Painting during the Reign of Fath-’Ali Shah.” The Contest for Rule in Eighteenth-Century Iran, edited by Charles P. Melville, I.B. Tauris, 2022, pp. 103-27. The Idea of Iran 11.

Qazvini, Abulhassan. Favaʿed al-safavaie, edited by Maryam Mirahmadi. Moassesseh motaleat wa tahqiqat farhangi, 1367/1988.

Robinson, Basil W., editor. L’Orient d’un collectionneur: miniatures persanes, textiles, céramiques, orfèvrerie rassemblés par Jean Pozzi. Musée d’art et d’histoire, 1992. Catalog of the eponymous exhibition, 9 Jul. – 18 Oct. 1992, Musée d’art et d’histoire, Geneva.

Rumlu, Hassan Beyg. Ahsan al-tawarikh, edited by Abdulhussein Navai, Babak, 1357/1979.

Schmidt, Hanns-Peter. “S. v. Simorḡ.” In Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition, https://referenceworks.brillonline.com/entries/encyclopaedia-iranica-online/simorg-COM_188?s.num=0&s.f.s2_parent=s.f.book.encyclopaedia-iranica-online&s.q=SIMOR%E1%B8%A0. Accessed 30 Aug. 2023.

Shahnama-yi Shah Tahmasp, edited by Ehsan Aghaei, Tehran Museum of Contemporary Art, 1400/2021.

Welch, Stuart Cary. A King’s Book of Kings: The Shah-Nameh of Shah Tahmasp. Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1976.

Acknowledgements

Our gratitude goes to Rudi Matthee for his precious comments on this article.