How to cite

Abstract

This article challenges the interpretation of Fahrelnissa Zeid’s (1901–1991) mid-century abstract production as influenced by Islamic and Byzantine art. The study analyzes culturalist presentations of the artist’s exhibitions in Paris galleries (1949–1969) and later international exhibitions (1990–2024), comparing them with the artist’s own statements and alternative reviews. I argue that both twentieth century and contemporary interpretations of her abstract practice are orientalist in character. The original elision of her voice reflected mid-century colonial ideology and promoted a new Parisian lyrical abstraction movement, while contemporary interpretations elevate globalized exhibitions’ marketing over scholarship. These culturalist interpretations exclude Fahrelnissa Zeid from modernism’s narratives by framing her practice as a-historic cultural atavism. I argue that Fahrelnissa’s approach to abstraction was shaped by her preoccupation with all-encompassing other-worlds. Her transition to abstraction followed a figurative expressionist phase and was triggered by paradigm-shifting visual shocks, leading to a two-decade gestural expressionist production. Fahrelnissa Zeid’s artistic vision also differs from some Global South modernist artists’ practice who sought to hybridize their national cultural imageries with European visual styles.

Keywords

Fahrelnissa Zeid, New School of Paris, Turkey, Abstract art, Orientalism

This article was received on 28 August 2024, double-blind peer-reviewed, and published on 14 May 2025 as part of Manazir Journal vol. 6 (2024): “Les artistes du Maghreb et du Moyen-Orient, l’art abstrait et Paris” edited by Claudia Polledri and Perin Emel Yavuz.

Introduction

“She should long ago have joined

France’s artistic pantheon.”1

The above quote is a paradoxical appreciation about Fahrelnissa Zeid (1901–1991), today overlooked in Paris despite the city hosting many of her postwar exhibitions.2 Yet, it is also a timely appreciation given the contemporary art world’s widening of the modernist canon with (re)discoveries of female and Global South modernists. Fahrelnissa’s reputation has benefited from this trend with record auction sales and new exhibitions—principally outside France. However, the interpretation of her abstract practice has not been updated since the 1950s, and is still characterized as adhering to ‘Islamic’ and ‘Byzantine’ aesthetics—ignoring her own remarks, as well as her involvement in two modernist art movements: The D Grubu in 1940s Istanbul and the Nouvelle École de Paris in the 1950s.

This article traces the genealogy of such orientalist interpretations, and the production and (re)production of Fahrelnissa Zeid as beholden to capacious categories of static and transhistorical cultural traditions. The argument is based on interviews and research into the artist’s archive that led to the publication of her biography in 2017, and on subsequent research into additional archives.3 This article begins with a presentation of Fahrelnissa Zeid’s life and career, then reviews the construction of her culturalist reputation during her abstract period in Paris from 1949 to 1969, and its revival in contemporary globalized museum contexts in Paris and London from 1990 to 2024. I deconstruct both periods’ judgements and compare them with the artist’s statements, and with non-orientalist reviews. I argue that, and elucidate why, both original and contemporary exegeses are orientalist in character. Further, I argue that Fahrelnissa Zeid’s approach to her practice as a whole was driven by a pursuit of expressive innovation. Fahrelnissa conceptualized her abstract practice as an exalted spiritual exploration, driven by her need to express her inner psychic universes and by a fascination with space.

Biographical and Career Overview

The young Fahrinnisa Şakir Kabaağaçli was born in 1901 into a family of intellectual Ottoman officials (fig. 3). She enrolled at Istanbul’s Women’s Academy of Fine Arts in 1919, but quit after her marriage. She travelled with her husband, modernist writer Izzet Melih Devrim (1887–1966), throughout the 1920s to Europe and visited museums. She had three children in a few years, including one who died in infancy. A turning point was when, on one of her travels, she enrolled in 1928 for a year at Paris’ Nabis influenced Académie Ranson and studied there under cubist painter, Roger Bissière (1886–1964). Upon her return to Istanbul, she abandoned her classicist drawings and turned towards expressionist painting. She re-enrolled at the Istanbul Fine Arts Academy, and participated in local exhibitions.

Fahrinnisa Devrim remarried the Iraqi diplomat, Prince Zeid Al-Hussein (1898–1970), in 1933 and Arabized her name to Fahrelnissa Zeid. In the following years, she had a fourth child, suffered from health breakdowns and a suicide attempt that led to multiple hospitalizations where doctors advised her to focus on art. She would later write that painting saved her life.4 Living in Istanbul during World War II, she painted expressionist cityscapes, interiors, nudes, symbolist scenes, and portraits. In 1941, she joined the avant-garde art collective D Grubu. She exhibited with the group before beginning to exhibit alone in 1945 to critical and commercial acclaim. However, she privately complained of being dismissed as a dilettante by some of her male colleagues and longed to affirm herself as an artist beyond Istanbul.5

In 1946, Fahrelnissa left Turkey after her husband was appointed to the United Kingdom. Once there, she held a number of solo exhibitions of her figurative output. She adopted abstraction in 1949 after undergoing a sensory epiphany on her first intercontinental flight over the fields of Southern England (fig. 8). Later that year, she held her first Paris solo exhibition at the Colette Allendy Gallery, met art critic Charles Estienne (1908–1966), and began splitting her time between London and Paris.

Estienne integrated Fahrelnissa Zeid into the cosmopolitan constellation of artists working in lyrical abstraction that he promoted in his attempt to revive the centrality of Paris’s prewar École de Paris. Eventually, she became a member of the Nouvelle École de Paris (NEDP) exhibiting at its first exhibition in 1952, and in most of its subsequent group shows. She also exhibited regularly at the international abstract showcase, Salon des Réalités Nouvelles, in addition to solo exhibitions in Belgium and Switzerland. Tristan Tzara, Fernand Léger and Francis Picabia visited Fahrelnissa’s exhibitions; Gisèle Freund photographed her; she made lithographs with Jacques Villon, was friends with Lynn Chadwick, and exhibited alongside Chagall.

In 1950, Fahrelnissa Zeid became the first Middle Eastern artist to have a solo exhibition in a New York commercial gallery. In 1954 she became the first female artist to have a solo exhibition at London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts.6 Her work was recognized by historians of modernism. In 1952, a book profiled Fahrelnissa alongside Hans Arp, Sonia Delaunay, Nicolas De Stael, and Vasarely.7 In 1960, she was included in another book of artists’ interviews, alongside Chagall, Miró, Kokoschka, Hepworth, Münter, and Henry Moore.8

After the 1958 Republican revolution in Iraq, Fahrelnissa lived as an exile in Europe. In the late 1960s, she revisited figuration via portraiture. She also invented a new artform with colored resin blocks encasing painted poultry and rabbit bones called Paléokrystalos. Fahrelnissa Zeid consistently experimented with different media: gouaches, prints, painted pebbles, painted sea rocks, and stained glass. Fahrelnissa then moved to Jordan in 1975, where she taught art. A 1981 group exhibition with her students contributed to the acceptance of abstraction in Jordan. In her last decade, Fahrelnissa Zeid focused on teaching and exhibiting, and privately painting portraits. She died in 1991.

Fahrelnissa had retrospectives in Turkey in 1964, Amman in 1983, and in 1990 at the Ludwig Sammlung Museum. In 2017, two posthumous retrospectives were held at London’s Tate Modern and Berlin’s Deutsche Bank KunstHalle, after which her works began to be regularly exhibited internationally. Many of Fahrelnissa Zeid’s works are held by international museums and art foundations. Fahrelnissa came to further prominence in the last decade, when some of her monumental abstract paintings broke auction records.

Practice

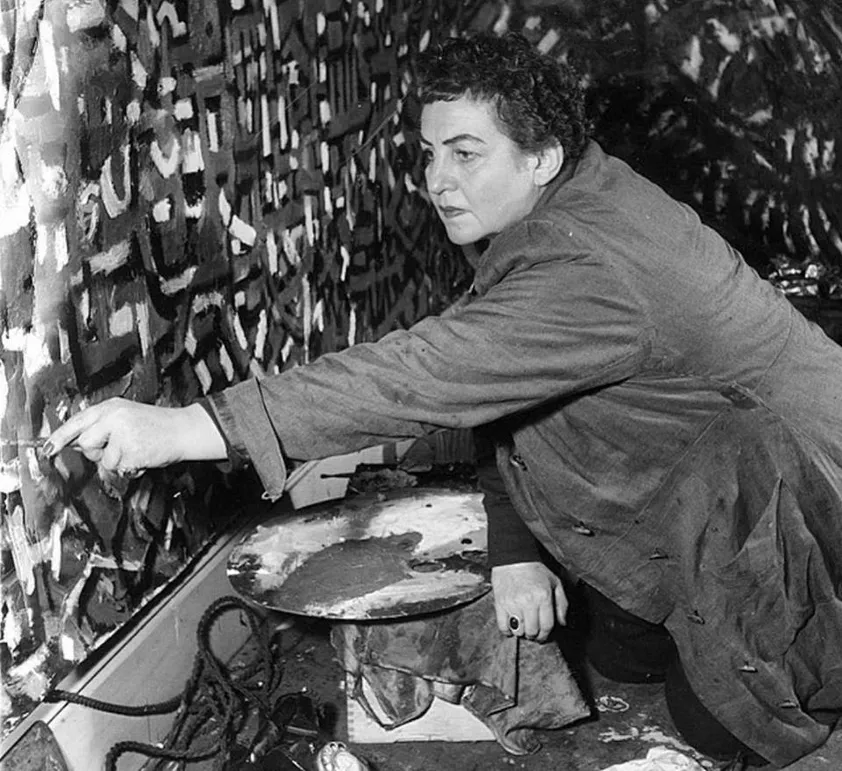

Fahrelnissa Zeid’s singular ambition allowed her to develop an innovative and prolific body of work. Her paintings are characterized by high painterliness and linearity. She was a swift worker, deploying considerable energy that allowed her to produce works requiring great intensity quickly, in addition to exploring new styles in rapid and overlapping sequences. Throughout her stylistic evolutions, she maintained a maximalist expressionist approach.

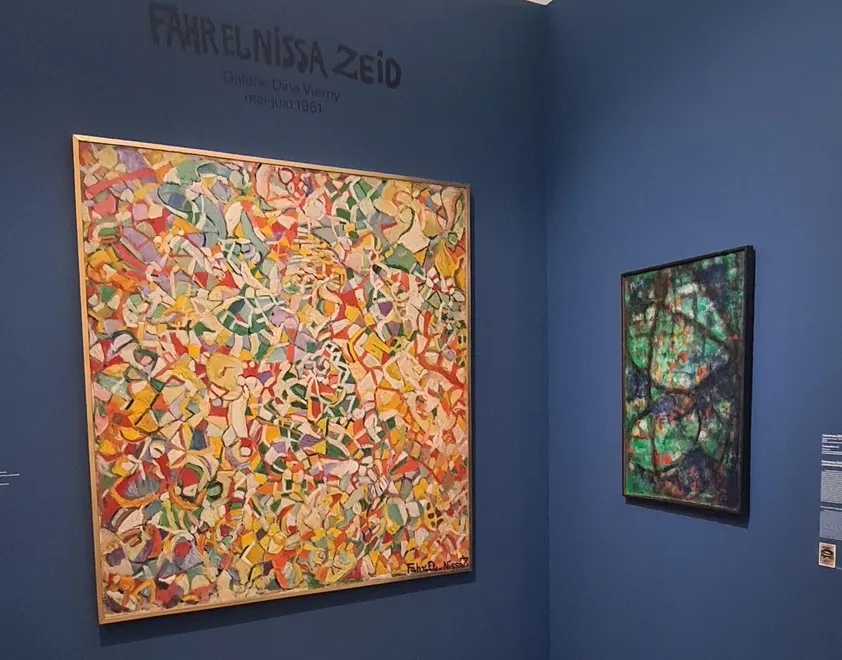

Fahrelnissa began her practice in earnest in the early 1940s as a figurative painter of symbolist works, expressionist portraits, nudes, cityscapes, and busy flat perspective interiors in saturated colors and thick impastos. After adopting abstraction in 1949, she would transpose the turmoil of her shifting moods onto her paintings with intense all-overs, and jarring contrasts of color and form. She often filled her larger gestural canvases with cadenced sub-compositions of fragmented colors and shapes, with divisionist effects. She also incised palette knife grooves onto impastoed surfaces. Thus, she created overwhelming and otherworldly universes of whimsy, cosmic voyages, and polychromatic murmurations (fig. 2).

Fahrelnissa Zeid began her transition to abstraction in 1947–1948 with psychedelic hybrid abstract-figurative compositions. Her fully abstract production can be roughly organized in five overlapping phases: first, a post-1949 experimental period of receding aerial views of geometrically abstracted agricultural fields; next, from 1950 to 1953 she transfigured those parcellated terrain abstractions into chromoluminarist vortexes (fig. 4 and fig. 6); she then transitioned to a maritime, sun-dappled phase (fig. 5); later, she reinvented herself with two shorter phases: first, producing dark canvases between 1954 and 1955 with primitivist geometric motifs, followed in 1956 to 1957 by works with a dark painterly unfolding linearity.

Fahrelnissa Zeid described these changes as motivated by a desire to search for a “style” that would suit her “particular temperament,” and move away from her “traditionally figurative” period.9 However, she also spoke of seeking satisfaction in surpassing herself: “As soon as I have attained a new angle in my composition and have exhibited my new work […] I struggle to express myself in a new way. Contentment in this new dimension to me signifies advancement.”10 A parallel output of two immersive and self-annihilating universes punctuate her oeuvre: maritime depths (fig. 9) and bi-chromatic astral worlds (fig. 1). Fahrelnissa also consistently produced monumental paintings that remain unrivalled by any woman artist of the immediate post-war period.

What unifies her abstract works? A forbidding intensity of scale and color? Dramatic lines and kineticism? Fahrelnissa Zeid’s teeming works proceed from the sublime, re-created not as natural or divine but as a psychic experience. Fahrelnissa’s sublime is a projection of her well-reported exalted absorption and boundless energy during the painting process.11 Her loss of self in painting also engulfs viewers.

Producing an ‘Oriental’ Artist

Like many Turkish modernists, Fahrelnissa Zeid was steeped in French culture and consequently focused her practice on Paris. Her high period there coincided with the new lyrical abstraction boom.12 From 1949 to 1961, Fahrelnissa had four solo abstract exhibitions whose presentation and reception constructed a fetishized, gendered, and orientalist artistic persona to account for her radically different output. She was presented as a female foreign artist in the grips of her essentialized culture(s) of origin—‘Islamic’ and ‘Byzantine’—who atavistically observed an Islamic ban on figuration. Although laudatory, reviews ignored Fahrelnissa Zeid’s extensive artistic training, previous figurative modernist practice, and statements. This was before the post-modern shift in art criticism influenced by scholarly perspectives, when critics were still free to invent artists’ personas. It is only after the heyday of the NEDP waned that Fahrelnissa received reviews that considered her words and engaged with her art on its own terms.

The reception of Fahrelnissa Zeid as an inherently oriental artist was established at her 1949 first Paris exhibition at the Colette Allendy gallery.13 Allendy asked the notable André Maurois (1885–1967) to write the catalogue’s preface. He praised Fahrelnissa’s work for its originality, but claimed it evoked “oriental carpets,” “primitive Byzantines,” and “Batiks of Java… dictated by her hereditary instincts,” among which are the influence of “Arab artists” to whom “figurative art was forbidden [...] [And who] had to express themselves by forms that had no other precise meaning than their beauty.”14 Maurois’ literary fantasies set the mold, and his text would define her reputation to this day as some reviewers and gallerists reprised it verbatim.

Estienne would amplify Maurois’ approach in writing about Fahrelnissa, in line with his project of developing a poetic critique. He was an admirer of the Nabis and Kandinsky, and was an ardent promoter of ‘warm’ lyrical abstraction in the 1950s via exhibitions and salons he organized.15 He also believed that abstraction posed a problem for audiences by not referring to concrete realities, hence requiring him to write a “poetic critique” to explain it.16 This resulted in a florid style, as in this text about Fahrelnissa Zeid’s 1951 exhibition which reads more like “an exercise in writing” than art “criticism”:17

And the light came from the Orient. And now the night is waking up again […] the brilliant and funereal kingdom where the mother goddesses of the East and the black virgins of the West keep watch, immobile, exchanging only their scepters. […] But they also depict, in a no less strange light verging towards a purplish violet, reds and blues circled by violent blacks […] And this light is the same, fabulous—Orientally fabulous—of Gothic stained glasses.18

Fahrelnissa’s gallery colleague, the Franco-Russian Serge Poliakoff (1900–1969) was also subject to culturalist interpretations at the start of his career. Some saw in his paintings reflections of Russian icons and folklore, and Estienne wrote that they resembled Bokhara and Samarkand carpets.19 Eventually, Poliakoff acquired French citizenship and was embraced by the Paris cultural establishment. However, the gendered orientalization of Fahrelnissa persisted, as illustrated by the comparison of her treatment with that of other artists by critics.

The Byzantine art historian Dora Ouvaliev (1921–1997) would surpass Maurois’ orientalism and assumptive dismissal of Fahrelnissa’s subjectivity. She mentions Fahrelnissa Zeid’s supposed “atavistic remembrance” and her works “full of sparkling light … sumptuous and rich – like a Byzantine mosaic … that is why [her] painting has so strange an aspect. […] Faithful to the ageless wisdom of the East […] her work bears witness to an extremely rich interior life. But the artist does not shelter behind the introspection inherent in westerners.”20 The same Ouvaliev, however, championed Poliakoff’s oeuvre and analyzed it without culturalist references, praising Poliakoff’s command of line and exploration of color, and considering him “a classic painter […] intemporal […] Having built his painting in the fundamental […] A principle that evokes revealed truth.” 21

Similarly, a review by art historian and friend of Estienne, C. H. Sibert, reviews side by side—and with equal lyricism—Fahrelnissa’s 1953 exhibition and one by her French-Portuguese NEDP colleague, Maria Helena Viera da Silva (1908–1992.) Sibert describes the former as a “medium” and an “heiress to Oriental legends,” bereft of agency, “pursued against her will by the myth of a lost Atlantis” whose paintings’ “lively, violent colors dance, jump, and organize themselves at last in a large mosaic that surprises even themselves.” In contrast, Sibert describes Viera da Silva’s compositions as spaces that she cuts through by her tracings, like “barrages” against the void, without referencing her Portuguese origins.22

Fahrelnissa Zeid’s subsequent two solo exhibitions’ presentation and reception followed the same format: an orientalist poetic preface by Estienne followed by laudatory but fetishizing reviews. Likely deferring to Estienne’s performative authority as patron of the NEDP, Fahrelnissa’s gallerists and reviewers amplified the critic’s mythological and orientalist clichés. Yet Fahrelnissa Zeid was pleased with her reviews.23 Coming of age decades before the epistemic shifts induced by Edward Said’s Orientalism, she could not be aware of the constricting reputational effects of these culturalist projections. Also, as a foreigner eager to make it in Paris, she may have preferred to defer to local figures’ performative expertise. It was only after 1958 that she began to distance herself from these characterizations.

Contemporary (Re)productions

The contemporary re-reading of Fahrelnissa has not shed culturalist taxonomies, as evidenced by her presentation in three Paris group exhibitions at the Institut du Monde Arabe in 1990, the Musée national d’art moderne/Centre Pompidou (MNAM) in 2021, and the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris (MAM) in 2024—with the latter two influenced by the earlier Tate retrospective in 2017. Rather than offering a fresh interpretation of Fahrelnissa’s complex practice for contemporary audiences, these institutions instead revived archaic and groundless taxonomies. In the case of MAM and MNAM, this was likely validated by the re-production of the orientalist etiology by the Tate. All the curatorial texts were fraught with errors, denoting a neo-orientalist perspective that implicitly deems a Middle Eastern artist unworthy of rigorous curatorial research.

In 1990, travelling from the Ludwig Museum, a Fahrelnissa retrospective was planned at the new Institut du Monde Arabe (IMA) in Paris. There, Fahrelnissa Zeid’s name had all but disappeared, since “the European canon [ignored] great female abstracts working in Paris [postwar.]”24 The NEDP itself was not an object of much interest. As a multidisciplinary institution, the IMA’s mission was to promote exchanges between France and Arab countries, and increase Arab culture’s presence in Paris. Perhaps because of this remit, Fahrelnissa Zeid’s IMA exhibition resulted in a culturalist and gender-driven flattening of art historical categories. Further, the promised solo retrospective featured instead two other self-taught artists: the Algerian, Baya Mahieddine (1931–1998), and Moroccan, Chaibia (1929–2004.)25

Erasing their differences in order to highlight common denominators of medium and gender, the exhibition was titled Trois Femmes Peintres. The catalogue’s preface justified joining these artists for their putative shared “strength of character that allowed them […] to impose themselves as women artists, despite the weight of social traditions.” A further curatorial statement eschewed historical accuracy, claiming that their works’ “formal freedom […] place[ed] them at the margin of movements and fashions.”26 The IMA catalogue texts about Fahrelnissa featured an article by Estienne full of mythological references, and a shorter insightful text by Bernard Gheerbrant.27 Still, the exhibition:

Definitively positioned Zeid’s work with that of the naïve, the untutored … Within this triad, Zeid […] is ‘disappeared,’ along with the forceful geometric abstract artist, the Paris years and triumphs, the enterprise of her determined female gallerists.28

In the decades since, the art world globalized, and new Biennials, museums, and multinational galleries proliferated. This international expansion was often guided by a commercial logic, while integrating new inflections of art critique and historiography by critical social studies, and post-colonial theory. As a result, the profile of contemporary artists from the Global South rose, alongside efforts at expanding the modernist canon to include more women, Queer, and Global South pioneers. Major Western museums like the Tate Modern in London, MoMA, the Guggenheim, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York developed initiatives to account for ‘global’ modern and contemporary art—and global patrons. These initiatives:

Helped generate a name for the institutions that increasingly make them a core part of their identity: ‘mega-museums’, a term that captures not just the large-scale ambitions of these museums’ broadening geographic scope but also the expansionist logic of the global capital that drives their activities. [...] In their search for historical figures that speak to contemporary concerns with global models of artistic practice, mega-museums have already begun to bring an unprecedented amount of scholarly and curatorial attention to long-ignored geographies of modern art.29

Fahrelnissa Zeid’s international profile rose after her death, as evidenced by increased acquisitions and exhibitions of her works in Turkey in the 1990s and 2000s by new Istanbul art institutions. This was followed by displays in Jordan and the Gulf in the same period and record-breaking prices at auctions in the 2010s. But it was her 2017 retrospective at Tate that markedly raised Fahrelnissa’s contemporary profile, and drove the subsequent boom of new solo exhibitions in Turkey and the UAE, as well as her inclusion in modernist group shows in Europe. Consequently, she was included in the 2021 self-proclaimed revisionist exhibition on the history of abstraction at the MNAM, Centre Pompidou. The Elles font l’abstraction showcase included over one hundred international women artists. The exhibition proposed a “rereading of the history of abstraction.”30 This claim, and a focus on artists’ gender rather than national identities presaged a reconsideration of Fahrelnissa’s practice. Still, orientalist filters were inexplicably conjured. The work exhibited included one of her large and kaleidoscopic high period paintings, Arena of the Sun (1954.) The catalogue’s biographical notice quoted Fahrelnissa Zeid’s explanation of why she chose to paint refracted colors.31 However, her own words were not enough, and her practice was still framed in orientalist terms—without substantiation—as deriving from a vision that “hark[s] back to her eastern origins.”32

She was then included in another Paris group show, this time with a regional focus: the 2024 Présences arabes. Art moderne et décolonisation. Paris 1908–1988 at the MAM in Paris. In the 1950s, the MAM was the site of Fahrelnissa’s monumental works’ unveilings when it hosted the Salon des Réalités Nouvelles. First opened in 1937, the MAM was not a mega-museum, but its collection of extra-European art made it a convenient setting for an exhibition on their model. However, the exhibition was hampered by general curatorial shortcomings.33 Further, Fahrelnissa Zeid’s incorporation was unwarranted, since the exhibition’s stated goal was the “historical rehabilitation and reconciliation of France with (post)colonial art history—its own history. Calibrated principally as a function of the process that led to the progressive decolonization of Arab territories.”34 Instead, Fahrelnissa’s inclusion was driven by her post-Tate notoriety, and by the possession of some of her works by MAM.35 These contradictory motives manifested in her works’ discrepant presence in the show, occupying dedicated space in the galleries, but nearly invisible in the catalogue texts (fig. 7).36 Her inclusion could have been justified by a necessary de-Orientalized reinterpretation of her practice, but the exhibition wall texts were marred by inaccuracies, and reproduced orientalist tropes.37 Fahrelnissa Zeid’s two paintings were presented under the trivial and sexist title of “Cosmopolitan Comet,” with the implied orientalism confirmed in the accompanying wall text: “Synthesizing its Byzantine, European and Islamic influences, these paintings captivate […] like […] a vault or a dome mosaic.”38 This conjuring of the ‘Islamic-Byzantine’ label was not substantiated, but had likely been legitimized by the Tate’s updated orientalism.39

The 2017 Fahrelnissa Zeid Tate retrospective raised her international profile. However, rather than developing a contemporary scholarly interpretation, its curation and marketing were grounded in unsubstantiated judgements that re-produced and hence authorized her orientalization. The Tate chose to center Fahrelnissa’s biography rather than her oeuvre: “This exhibition seeks to illuminate the influence of biographical and historical events on Zeid’s development as an artist.”40 What was illuminated, however, was an essentialized synthesis of Fahrelnissa Zeid’s perceived culture(s) of origin: “Patterns from Islamic architecture, Byzantine mosaics and the formal qualities of stained-glass windows […] all can be discerned […] in ways that are absorbing and mystifying.”41 This text implies that Fahrelnissa’s œuvre is beyond interpretation, befitting an epistemically inscrutable Oriental other. Further, the Tate abandoned undertaking an art historical analysis of her work, asking: “‘What school do her works spring from?’ The answers are complex and involve thinking across art historical and geographical boundaries to reflect on how different influences fused and enriched each other in her work.”42

Another Tate curatorial catalogue essay elaborated the orientalist etiology, replete with peremptory assertions, unsubstantiated projections, and selective citations.43 First, flanked by a stock photo of an inlaid wood Topkapi palace window set in an Iznik tiles bordure, a paragraph asserts: “Istanbul[’s] […] mixture of religions […] poetry and literature […] became key for Zeid, who […] incorporated these diverse elements into the practice.” Further, “Zeid’s abstract output was heavily inspired by the geometry found in Islamic and Byzantine mosaics; the rhythm of calligraphic motifs; and the philosophies of Eastern traditions.”44 These philosophies and traditions were alluded to but left unelucidated, and the claim of ‘heavy inspiration’ was not demonstrated by citations or references.

In another Orientalist amalgam, the monumentally abstract My Hell (1951), was deemed to “allude” to “influences” from figurative miniatures, and “Ottoman” windows.45 Another painting of multichromatic kaleidoscopic motifs was said to combine “influences drawn from mosaic and stained-glass designs inspired by Islamic and Byzantine motifs.”46 The designs go unidentified, and the claim of having inspired Fahrelnissa was unsupported by any reference. The text concludes with another claim about the ‘Eastern’ numinousness of Fahrelnissa: “Her attempt to approach abstraction as an environment but also as a form that constantly evolves and changes, based on a set of initial principles, reveals that the foundational language of the practice resides in the spiritual and philosophical underpinning of Eastern traditions […] Zeid’s approach was formulated in relation or a concept of nature as expansive form […] an idea we cannot grasp in its entirety.”47

Lastly, the Tate selectively edited and circulated a quote by Fahrelnissa Zeid appearing to claim her ‘Persian-Byzantine’ filiation that effectively portrayed her as sleepwalking through her heritage. The citation about her 1980 nostalgic self-portrait, Someone from the Past, is translated as:

I am a descendent of four civilizations. In my self-portrait ... the hand is Persian, the dress Byzantine, the face is Cretan and the eyes Oriental, but I was not aware of this as I was painting it.48

This statement is in fact excerpted from a longer statement by Fahrelnissa where she explains that the culturalist interpretation emanated from “some people” who wrote to her about it. She then explained the genesis of the self-portrait via her lifelong interest in motifs referencing astral phenomena:

I was thinking of the zodiac while making [painting] the dress. I was repeating myself without knowing really what the zodiac meant, and it is for this reason that I started making circles, squares, lines, repeating incessantly the same forms while insisting on this entanglement to express the zodiac.49

The shortcomings of the IMA’s 1990 exhibition may be attributed to its institutional mission of public diplomacy. However, the missions of specialized art institutions like the Tate, MNAM, and MAM manifest the intrinsically paradoxical strengths and weaknesses of the late capitalist museum: on the one hand, their unprecedented economic might allows them to employ internationally diverse and academically trained workforces and organize large shows of internationally sourced art, all while producing lavish publications and websites with detailed timelines, abundant reproductions, and rare archival images. Yet, this deployment of material power, which could underwrite new scholarship, is often undermined by a core contemporary institutional shortcoming: privileging the branded and sponsored spectacle of the exhibition-event: a spectacle unfolding via marketing, derivative gift shop products, and a deployment of globalized media messaging that mobilizes an exotic multiculturalism. Assuring the success of this spectacle overrides discretionary curatorial interest, leaving art historical inquiry and reappraisals to the slower temporalities of academia.

Construction

Texts from 1950s Paris and today manifest scant interest in the integrity of Fahrelnissa Zeid’s voice, neither faithfully quoting, researching, nor analyzing documented articulations of her vision and approach.. Fahrelnissa’s abstract works’ formal properties may be readily comparable to existing art historical categories ranging from Divisionism, Futurism, Orphism, Psychedelic art, Abstract Expressionism, Action Painting, and Lyrical Abstraction, to Op-Art (fig. 2). Instead of investigating these formal correspondences, critics and curators fell upon the facile production and reproduction of unsupported gendered and orientalist approximations. These assumptive claims that Fahrelnissa Zeid’s practice was dictated by her native culture(s) are unpacked here.

Four sources of influence are generally found next to Fahrelnissa’s name, contrived into a neologist rubric: Islamic-Byzantine-Ottoman-Persian. I argue that the affixing of these nebulous labels to account for her distinctive oeuvre proceeds from a reflexive Orientalism, thereby freeing critics and curators from furnishing a basic study of art historical inquiry—a labor rigorously afforded to Western artists. While the ‘Persian’ label is easily dismissible as fanciful, the ‘Byzantine’ label may derive from the fact that ‘Byzantium’s’ seat was in Istanbul, hence its ‘culture’ must have influenced Fahrelnissa Zeid as a resident.50 The trans-chronological ‘Islamic’ label likely derives from Turkey being a majority Muslim country, and thus its ‘Ottoman’ visual heritage ontologically dictates Fahrelnissa’s practice, regardless of its Tanzimat and Republican eras transformations.

The atavistic and nebulous ‘Byzantine’ etiology of her abstraction ignores Fahrelnissa’s 1940s modernist figurative practice, and is an iteration of Orientalist objectification. Ideologically, this term was associated with a subalternity of the historical realm of Constantinople within the Western European narrative of modernity as an ideological other.51 ‘Byzantinism’ is a product of categories of thought established from the Enlightenment onwards, when ‘Modernity’ as a politically and culturally superior construct was demarcated against an inferior medieval epoch. This process began with Gibbon who constructed an image of ‘otherness’ of a medieval Greek empire contra the true (Western) Roman Empire— the ancestors of Western European civilization. The image of a decadent ‘Byzantine’ culture provided the ideological ground on which its subaltern position vis-à-vis a regenerating Latinate Europe could be established in teleological narratives of historical progress. Notably, Hegel’s narrative of the triumph of reason and Christianity in early modern Western Europe picks up the baton of progress after the fall of the West Roman Empire.52 In the process, the Eastern Greek Christian Orthodox faith was described as unchanging, befitting the static nature of Eastern cultures assumed by orientalist discourse.53 Artistically, ‘Byzantine’ visual culture spans nine centuries of practices in multiple media alien to Fahrelnissa Zeid’s visual vocabulary: Byzantine art mainly represented church dogma via scenes of Paradisiac architecture, motionless human figures, and the Christian cosmos.54 Further, Fahrelnissa’s paintings of soaring murmurations, scattered triangles, and alveoli are characterized by dynamism and modulated scales. Her work contrasts with the ordered ornamentation of both Orthodox and ‘Islamic’ duplicative geometrical systems.

The 1950s Orientalist exegesis of Fahrelnissa Zeid’s art in the former capital of a colonial empire may be expected, but the contemporary resurgence is anomalous given the humanities’ postmodern and post-colonial turns. The latter method originated in Edward Said’s 1979 Orientalism, defined as the “discipline by which European culture was able to manage—and even produce—the Orient.”55 Revisiting his analyses reveals the rhetorical mechanisms of Fahrelnissa’s enduring Orientalization. Primarily an epistemic and perceptual system, Orientalism is articulated with power, assuming a number of dimensions:

A distribution of geopolitical awareness into aesthetic, scholarly […] texts […] a certain will or intention to understand […] control, manipulate, even to incorporate, what is a manifestly different […] world; it is, above all, a discourse […] produced and exists in uneven exchange with various kinds of power, shaped to a degree by the exchange with power political (as with a colonial or imperial establishment) […] power cultural (as with orthodoxies and canons of taste, texts, values), power moral (as with ideas about what ‘we’ do and what ‘they’ cannot do or understand as ‘we’ do.)56

According to Said, this created “an accepted grid for filtering through the Orient into Western consciousness.”57 The pervasiveness of Orientalism allowed for a “latent” structure that naturalizes the cultural other as a racial and gendered inferior. The latter served as a stable and durable epistemological framework that “kept intact the separateness of the Orient, its eccentricity, its backwardness, its silent indifference, its feminine penetrability, its supine malleability,” and even its “splendor.”58 The “Discourse about the Orient” is also manifest in representations of the Oriental woman who never speaks for herself, and never represents her presence or history. Rather, she is spoken for and represented.59

Further, Said rejected the understanding of the humanities as driven by the pursuit of 'disinterested' knowledge. He deemed that: “Fields of learning […] are constrained and acted upon by society, by cultural traditions, by worldly circumstance […] both learned and imaginative writing are never free, but are limited in their imagery, assumptions, and intentions.”60

NEDP artists produced largely recognizable medium scale formats of undulating colored abstractions, multichromatic stains behind grids, streaks of color, blurred patterns, and biomorphic aplats. Fahrelnissa’s distinguishable works “eclipsed those of […] her male counterparts.”61 It may thus have been expedient for the mainly male art gatekeepers to ‘keep intact her separateness’ behind a filter of gendered otherness, self-authorized by their translation of geopolitical awareness into aesthetic appreciations.

The 1950s gendered Orientalism of Fahrelnissa Zeid’s reception in Paris may have also been structured by historical patterns of reception of foreign artists set decades earlier. Since the 1920s, Latin American artists in the capital were beset by “expectations of primitivism.”62 The influx of foreign artists from all origins in the city had prompted calls for “the categorization of art into regional, national […] racial lines.”63 Perhaps as a result, “French critics frequently denied Latin American artists' agency in the artistic process by perpetuating the idea that, through race and culture, these artists had an inherent connection to the primitive or the exotic.”64

The contemporary anachronistic orientalization of Fahrelnissa may be conditioned by persisting latent intellectual structures as identified by Said, but may also be encouraged by the art world’s (re)discovery of some Global South modernists’ practices, particularly, those whose statements proclaimed their development of new creative national identities by drawing from their vernacular visual heritage blended with European modernist trends. The (re)discovery of these artists’ oeuvre is often grounded in a labor of recovery, translation, and post-colonial interpretation—a basic labor that has been denied Fahrelnissa Zeid. The assumptive interpellations of Fahrelnissa as an artist in thrall to her geography has yielded an epistemically violent triple elision: negating her statements, looking past her oeuvre, and erasing her from art scenes and histories she participated in and shaped.

Narrative Recovery

I cite in this section Fahrelnissa’s firsthand and reported reflections about her practice, inspiration and approach, followed by non-orientalist reviews. This recovery does not suggest alternative art historical taxonomies of her sprawling oeuvre. Rather, it highlights the wide gap between the artist’s culturalist characterizations and her avowed interests. This record reveals a self-aware artist who articulates her practice as an expression of her inner self, an exalted vision of art as psychic survival, and a hypersensitivity to color, movement, and space caused by varied life experiences. She distances herself from public commitments, avers existentialist concerns, and indicates she may have recognized her own approach in Kandinsky’s writings, notably, his conception of painting as “inner necessity” and communion with the universe.65 The reviews of Fahrelnissa Zeid’s work offered below exemplify diverse types of engagement with her work on its own terms, and hint at diverse avenues of future art historical interpretation.

Fahrelnissa ’s statements were always retrievable from three sources: her own published accounts of her artistic consciousness, reviews of her practice conducted in dialogue with her, and post-2017 scholarship. These sources belie the culturalist interpretations that naturalized her elision from histories of modernism. In a long-ranging 1959 interview, Fahrelnissa Zeid explicitly distanced her practice from hewing to political, religious, national, and even feminist interests or influences. Then, with self-awareness, she pointed to her introspective interests, and began by clarifying:

I have never been a student of Muslim art. I have never been particularly conscious of being an artist in this specifically Turkish tradition. Of course, I was brought up in this tradition […] I’ve also been conscious, at all times, of being an artist of the same generally ‘abstract’ school as many of my American, French or English friends and colleagues. I mean a painter of the ‘École de Paris’ rather than of any more specifically nationalist school.66

Fahrelnissa expressed her happiness at her erstwhile membership in the D Grubu, for the group’s experimental approaches before explaining:

I myself was never politically ‘engagée,’ but many other members of the group were. I shared their enthusiasm for an art that would no longer appeal exclusively to the well-to-do bourgeoisie […] [Similarly,] I’ve never been a militant feminist, and I hate to think of my paintings as expressions of a faith of this kind. They are both too personal and too impersonal to be interpreted as public statements. On the contrary, they surge within me from depths that lie far beyond peculiarities of sex, race or religion. When I paint, I feel as if the sap were rising from the very roots of […] [a] Tree of Life to one of its topmost branches, where I happen or try to be, and then surging through me to transform itself into forms and colors on my canvas. It is as if I were but a kind of medium, capturing or transmitting the vibration of all that is, or that is not, in the world.67

Fahrelnissa Zeid described her approach in such metaphysical terms from the start of her public career. In a 1952 interview, she quotes Spinoza and Pascal, and expresses her search for communion with an otherworldly cosmic energy. The salvation she mentions may be a reference to her depressive episodes:

Individual expression is found in a work of art; but […] there is also a boundless infinity outside of human awareness, and thereby a creative reality and way of salvation for the artist who finds therein his essence, his expression and his explanation […] I transpose the cosmic, magnetic vibrations that rule us […] I act as a channel for that which should and can be transposed by me.68

As for more prosaic questions about her paintings, she describes inspirations and causalities embedded in her life experiences, averring a hypersensitivity to color and movement. For example, she links her interest in painting refracted colors to her youth:

Since childhood I was impressed by light. I was attracted by the play of light on beveled mirrors, by the colors on their edges. I like light decomposed in a thousand facets. It is a strange world of fleeting colored movements […] In these flashes of light, the resulting fragmentation is already an analysis and an orchestration.69

She attributed the stimulus for her abstract turn to two visual and emotional shocks: the effects of the sight of advancing and vanishing ‘Bedouin’ women she saw in Baghdad in 1938, and experiencing transatlantic air travel in Spring 1949:70

I was a person working very conventionally with forms. But flying by plane transformed me. You see the horizon in front of you […] and then you enter the plane […] what a shock! The world is upside down. A whole city could be held in your hand: the world seen from above. I wanted to fix that in my head; I was stupefied [ahurie] the first time. When I went to America […] I watched from above the sky the little dots that were cars, houses, monuments. Your brain cannot accept this immediately […] it is so powerful! […] Another souvenir that played a role in my abstract evolution was during my first trip to the orient [sic] in Baghdad. I saw in the great expanses, the Bedouins ‘fly’ [...] from my window, I saw from dawn the very distant road, colored orange in the morning. This is how I saw six or seven silhouettes that came from the depth of the horizon, as if flying over the sands. I was petrified. They had on top of their heads a pyramid of pots of yoghurt, which looked from afar like very high chimneys […] and their veils floated in this gold [hue] that was ablaze. I ran to the window, but they had already passed […] This little event played a role in my abstract painting […] While looking at the Bedouin women, I was seeing space, speed, and movement.71

Original reviews and catalogues of Fahrelnissa’s exhibitions are available in newspaper and art institutions’ public archives. The non-orientalist Parisian reviews of her work were either written by critics outside Estienne’s orbit, or were published after the waning of the NEDP. While the initial orientalist conception of the artist was produced in 1949 by Maurois’ catalogue preface, his text was followed by an alternative appreciation. Art historian Denys Chevalier (1921–1978) engaged with the characteristics of Fahrelnissa Zeid’s work which he deemed “independent, solitary, and original […] rich, powerful.” He noted the contrast between the “miniaturist spirit” of the “indefinite fragmentation of planes” and the “monumental ambition of the technique and dimensions” of her works, translated in paintings of “mural character.”72 Still, it was Maurois’ literary interpretation that endured.

Art historian Julien Alvard (1916–1974) considered in 1951 that Fahrelnissa Zeid’s work had nothing to do with an “oriental déjà vu,” and characterized her style as “prolix, lively” with an “anarchic” line, and “melodic in the infinitely small, and symphonic on vast surfaces.”73 Alvard deemed Fahrelnissa’s first exhibition of lithographs “the most astonishing that one can see for some time.”74 Even an unfavorable review of Fahrelnissa’s first mixed abstract and portraiture show of 1961, that described it as “eclectic and uneven,” focused on the compositional features of her works, rather than veiling them in orientalist conjecture. The critic commended her “independence” and “strength of rebirth,” and highlighted her:

strict, tight graphics (weft and warp, or labyrinth) to glowing red organizations with stained-glass majesty, from Scottish-style marquetry to lyrical, swirling deployments of color […] [and her dilation of] a face to the dimensions of a large canvas, without succeeding in being figurative, rediscovering in this enormous unreal face the style and preoccupations of her abstract canvases.75

Significant non-Orientalist Parisian appreciations would have to wait until Fahrelnissa Zeid’s 1969 exhibition. These appraisals may have reflected changes in the art landscape following May 1968, as well as Fahrelnissa’s more humble and familiar social presence in a city where she was now living full-time as an exile. They may also account for Fahrelnissa gaining assurance to elucidate her approach, rather than defer to gatekeepers. The exhibition premiered her Paléokrystalos, alongside new oils of astral abstractions, and blurred underwater worlds. The catalogue texts were mainly written by the artist, and featured an excerpt from a diary entry where she articulated her thoughtful but ardent mindset when painting. The publication also included an excerpt from an admirative letter from André Breton (1896–1966).76

Numerous reviews responded to the sincerity of the catalogue and originality of the new works. A critic hailed Fahrelnissa Zeid as a reformer of modern art in her “reconstitution of an imaginary museum of prehistoric art.”77 The principal review was by art critic and founder of the legendary La Hune gallery, Bernard Gheerbrant (1918–2010).78 His was the first substantial review of Fahrelnissa’s to reject orientalist characterizations, referring to the influence of Kandinsky and Zeid’s interest in astronomical phenomena. Gheerbrant rejected Fahrelnissa Zeid’s assimilation to a ‘Scheherazade’ figure and wrote of her struggle with painting as a hand-to-hand combat. He also linked her vision to Kandinsky’s writings about art as “improvisations,” “impressions,” “compositions”: “the approach of one who feels in his depth of his being the struggle waged on the canvas shapes of opposed colors and trends […] on a cosmic scale where worlds and planets interfere dangerously.” Further, he framed Fahrelnissa’s exhibition as “a discovery of the hidden face of the Moon,”79 as it opened soon after the moon landing. Finally, Gheerbrant likened her entire approach to that of a demiurge seized by a cosmic passion in her manipulation of colors and shards of glass and bones to fashion a stellar world where the viewer becomes a “cosmonaut… projected in a sci-fi universe where speed and light make us encounter the images of the birth of man.”80

However, the time was not for forging new reputations for 1950s artists, but rather for their valedictory celebration. Fahrelnissa Zeid’s NEDP colleagues were representing France at the Venice Biennial or receiving public commissions and retrospectives. An apolitical seventy-year-old Middle Eastern woman in a Paris shaken by a post-1968 youth rebellion and artistic upheavals could hardly refashion her racialized reputation. Still, these texts demonstrate that orientalist narratives need not be a given for mid-century Paris critics and gallerists. These dissenting reports on the same influences on Fahrelnissa, with their descriptions of the same characteristics of her works, exemplify an engagement with the artist that allows the cathexis of her voice. These texts also make possible a productive re-contextualization of her oeuvre in the history of modernism.81

Lastly, new scholarship published in 2017 based on archival research and interviews with students and acquaintances of Fahrelnissa Zeid reveals an absence of culturalist interests, expands on the psychological linkages, and highlights her exalted chromatic and kinetic sensitivities.82 Absent from Fahrelnissa’s personal archives are references to ‘heritage’ as a source for her practice. Her notebooks are filled with citations of painting treatises, philosophy, psychology tomes, and articles on spatial advances. Her surviving library is composed of art and psychology volumes.83

Fahrelnissa Zeid’s anecdotal and conceptual articulations of her abstract turn and practice are precise and assured. Her statement about the visual shock caused by the gaimar sellers is substantiated by her profuse sketching of their depersonalized silhouettes, expressively representing in vigorous China ink lines the flapping dark folds of their abayas and the flashes of color of their dresses.84 As for her second inspiration for her abstract turn—the receding parcellated fields—it is confirmed in a reply to her son Raad’s (1936–) question about the ‘meaning’ of her abstract art, to which she answered that abstraction is how one sees the world from an airplane window.85 After she first saw the gaimar sellers in 1938, Fahrelnissa felt too unsure—by her own admission— to conceive shifting to abstraction.86 However, perhaps encouraged by her new familiarity with it in London and Paris, she started experimenting with abstraction in 1947. The visual shock experienced aboard the plane in 1949 may then have inspired her to adopt abstraction and obsessively elaborate upon that vision for years.

A more profound conceptualization for her switch appears in a December 1949 diary entry that restates her absolute quest for communion with cosmic other-worlds that she perceives but cannot see, and to recreate what she felt were their vibrations traversing her, hoping they would lead to a higher state of self:

The abstract has always existed. [In the past] we had to deal with perspective, composition, but this essential rhythm which was the hard nucleus of the work [of art] had to be dressed, furnished if one can say that for the satisfaction of the eye that searched for visual and sensual beauty. Today with the abstract, man has reached the summits—man goes towards the infinite—space—it is a window open from our world to other worlds. It is the reach of a boundless and limitless thought. It is the ultimate superiority of the human brain. Why must we always see with the eyes of this world, why not see farther, and enlarge the visual orb and reach even the divine, in a circle traversed by cosmic waves? […] So why hold on to primary and infantile details, a portrait, a chair, and a child? All this has been done and redone. It can add nothing to the spectator’s mind who wants to learn, to be struck by sensations, like one who searches for the north wind at sea in the midst of winter to feel washed, refreshed, and cleansed.87

Fahrelnissa Zeid conveyed her fascination with all things cosmic in her advice to her students in Amman.88 A former student describes her as ‘obsessed with the cosmos,’ as she would tell them that their paintings should be animated by balance and movement, echoing “cosmic movement” and “the rotation” of the “universe”.89 She stressed that movement was not “in straight line but in orbits.” 90 The students had to forget what they had learned to access that movement of the universe through “their inner self and unconscious.”91

Conclusion

This review demonstrates that Fahrelnissa Zeid’s practice was not informed by a will to articulate elements of her heritage with aesthetic modernism. The deliberate practice of some Global-South artists to hybridize their visual heritage with Euro-American styles has led to a range of decolonial art practices. However, ascribing the same approach to Fahrelnissa consigns her complex oeuvre to a dubious ahistorical realm of heritage automatism, and dooms all non-Western artists to heritage extraction. Fahrelnissa Zeid’s recorded preoccupations point instead to a psychological predisposition to commune with what she perceived as other-worlds, served by a great painterly skill and considerable ambition and energy. This led her to produce uniquely gestural abstract compositions with focused painterly layering, or kinetic sub-compositions (fig. 10). This approach had antecedents in the lines and impastos of her 1940s expressionist figurative period, and extends to the 1960s non-naturalist chromatics and palette knife incised faces of her portrait sitters.

Fahrelnissa projected her oft-stated desire to surpass herself psychologically and seek communion with other realms via her immersive paintings. After 1958, she hung her large abstract paintings on all the walls and even ceilings of her homes. In the late 1960s, she transposed that approach onto her Paléokrystalos that she set on revolving stands, backlit by multicolor lights projected onto her canvases and studio walls. A journalist visiting her in the 1980s deemed her home’s kinetic accumulations a “baroque Lascaux.”92 The multichromatic visions emerging from her psyche and projected onto her surroundings via her art, would no doubt have led her, had she lived in more technologically advanced times, to create even more immersive infinite experiences.

Bibliography

Adamson, Natalie. Painting, Politics and the Struggle for the École de Paris, 1944–1964. London: Routledge, 2009.

Alaoui, Brahim Ben Hossain. “Préface.” In Trois Femmes Peintres [Baja, Chaibia, Fahrelnissa], no editors, 5. Paris: Institut du Monde Arabe, 1990. Exhibition catalogue.

Alvard, Julien. “Fahr El Nissa Zeid. Galerie de Beaune.” Art d’aujourd’hui, 1951.

⸻ et al., eds. Témoignages pour l’Art abstrait, Paris: Éditions d’Art d’Aujourd’hui, 1952.

Breton, André. “Lettre d’André Breton à Fahrelnissa Zeid.” In Fahrelnissa Zeid, no editors, n.p. Paris: Galerie Katia Granoff, 1969. Exhibition catalogue.

Centre Pompidou. “Elles font l’abstraction.” Presentation, 2021.

https://www.centrepompidou.fr/fr/programme/agenda/evenement/OmzSxFv.

Collis, Maurice. The Journey Up: Reminiscences 1934–68. London: Faber & Faber, 1970

Chevalier, Denys. “Fahr-El-Nissa Zeid.” In Fahr-El-Nissa Zeid, no editors, n.p. Paris: Galerie Colette Allendy, 1949. Exhibition catalogue.

Encyclopædia Britannica Online, s.v. “Byzantine art.” Accessed 5 March 2024. https://www.britannica.com/art/Byzantine-art.

Estienne, Charles. Midi Nocturne. Paris: Editions de Beaune, 1951.

Gheerbrant, Bernard. “L’odyssée de Fahr el nissa Zeid,” La Galerie des Arts, no. 76, 15 September 1969, 26–7.

Greenberg, Kerryn. “Tate Modern. Fahrelnissa Zeid.” London: Tate Modern, 2017. Exhibition brochure.

⸻. “The Evolution of an Artist.” In Fahrelnissa Zeid, edited by Kerryn Greenberg, 11–27. London: Tate Modern. 2017.

Greet, Michele. Transatlantic Encounters: Latin American Artists in Paris Between the Wars. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2018.

Gronlund, Melissa. “How Arab is Paris? Art History Might Have the Answer.” The National, 10 July 2024.

https://www.thenationalnews.com/arts-culture/2024/07/10/arab-presences-modern-art-paris/.

Harambourg, Lydia. “The 50s in Paris 1945/1965.” Applicat-Prazan, Accessed 31 March 2025 https://www.applicat-prazan.com/en/second-school-of-paris/.

ICA. “Complete ICA Exhibitions List 1948–Present–July 2017.” Accessed 31 July 2024. s.d. https://archive.ica.art/about/history/index.html.

J., E. “Le Lascaux baroque de Fahrelnissa Zeid.” Le Monde, 14 November 1989. https://www.lemonde.fr/archives/article/1985/11/14/le-lascaux-baroque-de-fahrelnissa-zeid_2751485_1819218.html.

Kelaidis, Katherine. “The Art World’s Orientalist Fantasies About the Byzantine Empire.” Hyperallergic, 2 January 2024.

https://hyperallergic.com/840865/the-art-worlds-orientalist-fantasies-about-the-byzantine-empire/.

L., M. C. “À travers les galeries.” Le Monde. 2 June 1961.

https://www.lemonde.fr/archives/article/1961/06/02/a-travers-les-galeries_2281678_1819218.html.

Laïdi-Hanieh, Adila. “Fahrelnissa Zeid, Towards a Sky.” Smarthistory. 16 December 2024. Accessed 21 January 2025.

https://smarthistory.org/fahrelnissa-zeid-towards-sky/.

⸻. “1/2: My feedback on the inclusion of Fahrelnissa Zeid in the new ‘Présences arabes’ exhibition.” Instagram photo, 5 April 2024.

https://www.instagram.com/p/C5W2Mw6oa7g/?img_index=10.

⸻. “2/2: My feedback on #PrésencesArabes show after I got to see it in person at the @museedartmoderndeparis.” Instagram photo, 9 May 2024.

https://www.instagram.com/p/C6wnOCOrAJ7/?img_index=1.

⸻. Fahrelnissa Zeid. Painter of Inner Worlds. London: Art/Books, 2017.

Lenot, Marc. “Le grand écart de ‘Présences arabes.’” Lunettes Rouges (blog). 29 May 2024.

https://lunettesrouges1.wordpress.com/2024/05/29/le-grand-ecart-de-presences-arabes/.

Milad, Mondher. “À travers les galeries.” Combat, 3 November 1969.

Maurois, André. The Oriental Painter Fahr-El Nissa-Zeid. (New York: Hugo Gallery, 1950).

Montazami, Morad. “Paris capitale arabe: la modernité déchirée et partagée.” In Présences arabes. Art moderne et décolonisation. Paris 1908–1988, edited by Odile Burluraux, Madeleine de Colnet and Morad Montazami, 8–15. Paris: Editions Paris Musées, 2024.

Montjovet, Félix. “Art moderne et décolonisation: les artistes arabes du xxe siècle en pleine lumière.” Jeune Afrique, 2 August 2024.

https://www.jeuneafrique.com/1588376/culture/art-moderne-et-decolonisation-les-artistes-arabes-du-xxe-siecle-en-pleine-lumiere/.

Nasser, Hind. Interview with the author, 1 October 2016.

Neel Smith, Sarah. “Fahrelnissa Zeid in the Mega-Museum. Mega-Museums and Modern Artists from the Middle East.” Ibraaz, no. 161 (14 July 2016): 1–10.

https://www.ibraaz.org/usr/library/documents/main/fahrelnissa-zeid-in-the-mega-museum.pdf.

Oikonomopoulos, Vassilis. “Multiple Dimensions of a Cosmopolitan Modernist.” In Fahrelnissa Zeid, edited by Kerryn Greenberg, 45–56. London: Tate Modern. 2017.

Orgeval, Domitille d’. “Fahrelnissa Zeid.” In Elles font l’abstraction, edited by Christine Macel and Karolina Ziebinska-Lewandowska, 188–189. Paris: Éditions du Centre Pompidou, 2021. Exhibition catalogue.

Ouvaliev, Dora. “Triumph of Abstract Art.” Art News and Review, 1949. N.p.

Parinaud, André. Fahr El Nissa Zeid. Amman: Royal National Jordanian Institute Fahrelnissa Zeid of Fine Arts, 1984.

Raad, Prince. Interview with the author, 10 October 2016.

Reymond, Nathalie. “Charles Estienne, critique d’art.” In Travaux XIV. Geste, Image, Parole, edited by Pierre Charreton, 39–50. Saint-Étienne: CIEREC-Université de Saint-Étienne, 1976.

Roditi, Edouard. Dialogues on Art. London: Secker & Warburg, 1960.

Said, Edward W. Orientalism. New York: Vintage Books, 1979.

Sibert, C. H. [Exhibition review] Réalités Poétiques, January 1954. N.p.

Stouraitis, Yannis. “Is Byzantinism an Orientalism? Reflections on Byzantium’s Constructed Identities and Debated Ideologies.” In Identities and Ideologies in the Medieval East Roman World, edited by Yannis Stouraitis, 19–47. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press 2022.

https://doi.org/10.3366/edinburgh/9781474493628.003.0002.

Tate. “Fahrelnissa Zeid in four key works.” Accessed 31 March 2025.

https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/fahrelnissa-zeid-22764/four-key-works.

Vallier, Dora. “Poliakoff en 1986.” In Dora Vallier, Serge Poliakoff, 11–14. L’Isle-sur-la-Sorgue: Association Comprendre Art et Culture, 1986.

Wilson, Sarah. “Extravagant Reinventions: Fahrelnissa Zeid in Paris.” In Fahrelnissa Zeid, edited by Kerryn Greenberg, 89–103. London: Tate Publishing, 2017.

Zeid, Fahrelnissa. Diary, 2 December 1949. Fahrelnissa Zeid Archive, Amman, Jordan. N.p.

⸻. Draft letter to Maurice Collis. 14 February 1948. Fahrelnissa Zeid Archive, Amman, Jordan. N.p.

⸻. Speech to Visitors, Amman open house. 18 November 1976. Fahrelnissa Zeid Archive, Amman, Jordan. N.p.