How to cite

Abstract

Saliba Douaihy, Shafic Abboud, and Saloua Raouda Choucair were three Lebanese artists who traveled to Paris in the process of becoming canonical artists in their home country. But Paris was not their only destination. For all three of these artists, their intercity movements produced an experience of cosmopolitanism that was circulatory and nonhierarchical. This cosmopolitanism did not flow only one way. Rather, it pooled as artists took advantage of opportunities to travel and moved back and forth between different transnational hubs. This article explores how cosmopolitanism operates, as a pattern of movements and a mode of exchange, and questions the connections among cosmopolitanism, modernism, and abstraction. Drawing on recent scholarship to define cosmopolitanism as a mixture of languages and a density of encounters, I argue that artists such as Douaihy, Abboud, and Choucair exemplified the linguistic phenomenon of heteroglossia in the visual arts. These artists approached abstraction not as a style to imitate but rather as a language to use, one easily interchangeable with the others they already spoke fluently. I propose that if we, too, approach abstraction, metaphorically, in linguistic rather than stylistic terms, then we will develop the tools to reformulate modernism as expansively global.

Keywords

Travel, Migration, Diasporic Imagination, Abstraction, Agency

This article was received on 19 September 2024, double-blind peer-reviewed, and published on 14 May 2025 as part of Manazir Journal vol. 6 (2024): “Les artistes du Maghreb et du Moyen-Orient, l’art abstrait et Paris” edited by Claudia Polledri and Perin Emel Yavuz.

A Scattered and Unruly Map: Beirut, Paris, and Beyond (Introduction)

Hussein Madi (1938–2024) studied in Rome. Mohamed Rawas (b. 1951) lived in London. Rafic Charaf (1932–2003) won a government scholarship to Madrid. Bibi Zoghbi (1890–1973) emigrated to a small city in Argentina and then, after divorcing, made a life of her own in Buenos Aires. Seta Manoukian (b. 1945) passed through Rome and London on her way to becoming a Buddhist nun in Los Angeles. Etel Adnan (1925–2021) lived in the San Francisco Bay Area. Huguette Caland (1931–2019) built a house in Venice Beach. Yvette Achkar (1928–2024), quintessential Beiruti, was born and raised in Brazil. Helen Khal (1923–2009) grew up in Pennsylvania. Farid Haddad (b. 1945) received a Fulbright to learn printmaking in New York and ended up settling in New Hampshire. Jamil Molaeb (b. 1948) traveled to Algeria before earning degrees from the Pratt Institute and Ohio State. The journey that proved most transformative for Ibrahim Marzouk (1937–1975) took him to Hyderabad in India. Samia Osseiran Junblat (1944–2024) attended art schools in Florence and Tokyo. Aref Rayess (1928–2005) spent much of his childhood in Senegal. For years, Amine El-Bacha (1932–2019) thought of Spain as home.

If one were to chart only the most dramatic movements of these fifteen artists, all of whom figure prominently in the stories of Lebanon’s modern art, one would end up drawing a scattered and unruly map.1 There would be lines darting across oceans, trajectories crossing from one hemisphere to another, and no obvious points of convergence. It is often said that four times as many Lebanese are living outside of the country as inside of it. Waves of immigration due to war, famine, colonial domination, and governmental failure have defined Lebanon for more than a century. Both the Lebanese political system and the structure of its economy depend on a flood of citizens out of the country into exile, with their deposits and remittances washing back like the tide. Across the diaspora, there are concentrations of Lebanese settled in the Gulf, West Africa, Latin America, and Dearborn, Michigan. But there is no single bottleneck through which all Lebanese émigrés must pass.

In his study of Lebanon titled Warlords and Merchants, the economist Kamal Dib locates the origins of modern Beirut in the sixteenth century, when European engagement with the eastern Mediterranean created the conditions for Lebanon’s penetrated economy.2 That was the moment when the Ottoman sultan, Suleiman the Magnificent, extended certain privileges (also referred to as capitulations) to France, as well as to Russia, England, and the Italian city states. This marked the beginning of Beirut as a Levantine city. Its status as a cosmopolitan center, then and by extension now, derived from its mercantile port, openness to foreign ideas, and interaction among ethnically, religiously, socioeconomically, and linguistically mixed communities.

By the nineteenth century, French missionaries were present throughout Lebanon. French financiers helped to reconstruct the port, build new roads, and establish a railway network, all of which altered how Beirut connected to the wider world. With the collapse of the Ottoman Empire at the end of World War I, France took control of former Ottoman territories cobbled together under the name of Greater Lebanon. The French Mandate lasted only a few decades and involved little outright violence compared to the brutal colonization of Algeria.

The French Mandate was, however, an overall condescending and coercive operation. Because the French established many of the institutions of the Lebanese state, because they built schools and universities and distributed scholarships to study in France, because they imposed the French language and valorized elements of French culture in the name of la mission civilisatrice, Paris became a major point of reference. This remained the case even—and in fact more so—after Lebanon gained independence from France in 1943.

No one knows exactly who gave Beirut its nomenclature as the Paris of the Middle East, or when. It was the French poet Alphonse de Lamartine who named it the Switzerland of the Levant, not, as would later become the case, because of Beirut’s embrace of banking secrecy but rather due to its mountain views.3 And Beirut was never the only Paris of the eastern world. At various points Shanghai, Pondicherry, and Saigon, among others, adopted the name as a tourist slogan. Still, the relationship between Paris and Beirut has been long, complicated, and uneven, which accounts, in part, for why the French capital occupies such a strange and disproportionate place in the Lebanese diasporic imagination.

In terms of economic growth and cultural dynamism, Beirut thrived in the decades after World War II. But France continued to exert a substantial and not always benevolent influence over its ex-colonies. Paradoxically, avant-garde artists and writers from across the Arab world would go precisely there, to Paris, to bristle with their desire for decolonization and to forge national identities in the place and within the structures of power that had fought hardest to delay their emergence.4

The presence of such artists and writers made Paris a thrilling and heterogenous place, and this created a double paradox. As the writer Coline Houssais explains in her book Paris en lettres arabes, the historical imbalance between Paris and the Arab world was complicated: “First, the French fascination with Arab culture and contempt for those who embody it. Then, the Arab paradox of seeing in France both the colonial monster to be fought and the model of society and political organization to be followed.”5

And yet, this view of the Paris-Beirut dyad ignores what was happening “on the other side of the Mediterranean.”6 According to the art historian Zeina Maasri:

Beirut in the long 1960s developed as a nexus of transnational Arab artistic encounter, aesthetic experimentation, intellectual debate and political contestation. Its cosmopolitanism was not directed only at Euro-American modernism and not limited to a Lebanese nationalist subjectivity. Rather, it was formed by competing transnational circuits of modernism and the mobility of its enunciating subjects, not least Egyptian, Palestinian, Syrian and Iraqi artists and intellectuals who weaved through the city, in and out of its flourishing art galleries, publishing industry, and tourism and leisure sites.7

Paris may have mistaken itself for the world, but Beirut had always known otherwise. In 2022, the Musée de l’histoire de l’immigration in Paris mounted a promising exhibition of works by twenty-four foreign artists who passed through Paris between 1945 and 1972. The show, organized by the curator Jean-Paul Ameline, opened with the title “Paris et nulle part ailleurs” (Paris and Nowhere Else), which was both a winning assertion and a meaningful provocation. As the fifteen aforementioned artists from Lebanon demonstrate, in the years following the end of World War II, there was in fact Paris and everywhere else. A reconsideration of these artists’ movements is enacted here to pull Paris down from its pedestal and to see what happens when the French capital is reinserted onto the scattered map of Lebanon’s most geographically adventurous artists.

Saliba Douaihy, Shafic Abboud, and Saloua Raouda Choucair (Notes on Method)

Saliba Douaihy (1915–1994), Shafic Abboud (1926–2004), and Saloua Raouda Choucair (1916–2017) were three among many Lebanese artists who traveled to Paris in the course of their artistic maturity and in the process of becoming canonical figures. In this, they were not alone. Throughout the twentieth century, hundreds if not thousands of Lebanese artists spent time in the French capital. But as with their peers who ventured across Asia, Africa, and Latin America, Paris was not their only destination. For Douaihy, the more consequential city was New York, where he developed his signature approach to abstraction. For Choucair, Paris was just one in a larger constellation of cities that shaped her work, including Cairo, Alexandria, Baghdad, Kirkuk, and Beirut. Only Abboud decided to stay in Paris, settle down, and become French.

Yet for all three artists, their intercity movements—back and forth from Beirut to Paris and elsewhere—produced an experience of cosmopolitanism that was circulatory and nonhierarchical. It did not flow only one way, downward from the colonial metropole to the former province. Rather, this cosmopolitanism pooled as artists took advantage of opportunities to travel and moved among transnational hubs. For Douaihy, Abboud, and Choucair, Beirut had always been a mixed, charged, and complex city. It was as cosmopolitan as Paris, and the three had already been formed as cosmopolites before they left one city for the other.

The purpose of this article is to recalibrate the relationship between Beirut and Paris by exploring how cosmopolitanism operates as a pattern of multidirectional movements and a mode of international exchange. It is also to question the connections among cosmopolitanism, modernism, and abstraction. Was it a coincidence that Douaihy, Abboud, and Choucair all found their way to Paris, to an abstract language, and then pushed that language for decades, creating bodies of work both remarkably consistent and internally coherent? Moreover, does it pose a useful challenge to art history that for each artist their abstract language was actually a mix of several languages and dialects and accents, a complex and striated discourse linked to other modes of expression, such as landscape and religious painting, storytelling and mapmaking, poetry and geometric patterning as old as the twelfth century? Do these examples of cosmopolitanism as a circuit, a community of multilingual artists, and the coexisting formal attributes of artworks themselves have something more to tell us about what modernism is or was?

Drawing on the writings of Partha Mitter, Kobena Mercer, and Kwame Anthony Appiah, among others, I define cosmopolitanism as a mixture of languages, an amalgamation of communities, and a density of encounters occurring in one place that is open to others. Cosmopolitanism is thus marked by contamination (in Appiah’s phrasing), discrepancy (in Mercer’s), and enrichment tinged with resistance and rebellion (in Mitter’s). As such, cosmopolitanism, while often asymmetrical and uneven, is pointedly not universal or generic. Rather, it is intensely contextual. To understand how artists such as Douaihy, Abboud, and Choucair moved through their cosmopolitan circuits—and why they should be better known internationally—requires considering a wealth of detail about their lives and works. My hope is that such detail, in the form of unwieldy case studies, will prove so overwhelming as to break the western canon, giving us the occasion to make something new, better, and different from its pieces.

To this end, I revisit the stories of how Douaihy, Abboud, and Choucair became artists, traveled to Paris, experimented with different modes of artmaking, and tested out pathways to abstraction. The aim is to illustrate how Paris figures differently in the accounts of each artist. For Douaihy, it was inconsequential. For Abboud, it was his dragon to slay and his mountain to conquer. Only for Choucair was it considered her rite of passage, an initiation into the modern. But the point is also to stress each artist’s individual agency, something too often ignored in non-western case studies. Douaihy was indifferent to Paris. Abboud embraced it in a complicated way. Only Choucair, again, was above all strategic about her time in France.

From these stories, I focus on the tensions running through critical receptions, drawing out the extent to which these artists have already been cast in linguistic terms. On this point, I turn briefly to Mikhail Bakhtin’s concept of heteroglossia, the idea that multiple languages and styles of discourse exist within a novel, such that meaning is changeable and context-dependent. Due to Beirut’s rich linguistic terrain, Douaihy, Abboud, and Choucair were all, to an exaggerated degree, at ease with multilingualism and diglossia, using multiple versions of a language depending on social codes and circumstances, both formally, in their art, and conversationally, in the multiple worlds they operated in. Applying heteroglossia to the visual arts, I suggest that if to be multilingual was to be cosmopolitan and to be cosmopolitan was to be modern, then one can work in reverse, using linguistic phenomena metaphorically to dismantle modernism as a unifying narrative.

Each in their own way, Douaihy, Abboud, and Choucair approached abstraction not as a style to imitate but rather as a language to use—one that was easily compatible, swappable, and interchangeable with the others they already spoke fluently and played with visually. I propose that if we, too, approach abstraction, metaphorically, in linguistic rather than stylistic terms, then we will develop the concrete tools and methods to move beyond the limitations of art history to reformulate modernism as expansively global.

“Dignity is non-hierarchical,” writes the philosopher Martha Nussbaum in her study of the cosmopolitan tradition in western political thought.8 The discipline of art history, however, has always been steeply tiered, nowhere more so than in its formulation of modernism, which, according to the art historian Partha Mitter, “tends to undermine local voices and practices, thereby undermining the plurality of expressions.”9 As a result, non-western artists have been written out of the history of modern art. Worse, scholars have dismissed them as derivative or belated, a move that Mitter describes vividly as the syndrome “Picasso manquée.” Museums have exhibited non-western artists as cultural ambassadors or exotic aberrations from the norm, artists who came from nowhere like meteors crashing through a nighttime sky.

As the curator Adriano Pedrosa points out, tools of art history such as the canon have constructed an apparatus of imperialism and colonization that has outlasted actual imperialism and colonization.10 Many scholars have diagnosed the problem of art history’s limited scope and narrow vision. Curators such as Pedrosa and the late Okwui Enwezor, among others, have offered a raft of possible solutions in exhibition form. My hope is to propose a mixed, impure, nonhierarchical, and multilingual cosmopolitanism as part of an art historical and art critical method for remaking modernism as global—without falling into what the art historian Prita Meier has defined as the “authenticity paradox.”11

The leveling of the Paris-Beirut relationship is therefore both a corrective and a proposition. To reconceive of cosmopolitanism as a nonhierarchical circuit would have the symbolic effect of returning some measure of dignity and plurality to art history. It would have the more practical effect of elevating regional art histories while again downplaying the mythologies of Paris. This would help to dismantle the center-periphery model while allowing for the reformulation of Beirut and cities like Beirut as central nodes in a matrix of overlapping cultural systems and as critical sites of international exchange.

Saliba Douaihy: A Case Study on Abstraction as Landscape and Religious Painting

Saliba Douaihy was born in the mountains east of the port city of Tripoli in 1915.12 There were no fine art museums in the north of Lebanon at the time, but the twinned villages where Douaihy was from, Ehden in summer, Zgharta in winter, were steeped in religious painting. His childhood exposure to art came through books, illustrated editions of La Fontaine’s fables, and church. As a teenager, Douaihy spent several years apprenticing with the artist Habib Srour in his Gemmayzeh studio. The teaching there was traditional and technical. Srour did not allow Douaihy to use any color at all.13

In 1932, Douaihy’s family, the Maronite Church, and the Lebanese government raised funds to send him to Europe. Douaihy wanted to go to the Vatican but was sent to the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris instead. By all accounts he excelled there. His drawings from this period—nudes, small portraits, sketches of biblical figures—are delicate and precise. But he was indifferent to modern art, preferring only that which was strictly classical.14 The cultural dynamism of interwar Paris meant nothing to him.

After graduating, in 1936, Douaihy did make it to the Vatican, detouring in Rome on his return to Beirut. Commissioned to do ceiling frescoes for a church in Diman, he was most struck by the work of Michelangelo and Raphael, whose styles he appropriated for his own religious paintings. Back in Lebanon, Douaihy opened a studio in Ras al-Nabaa. In the decade to follow, he became one of Lebanon’s most successful artists, adored by the local public, equivalent to an artist laureate. He painted shepherds, churches, modest dwellings, and majestic trees. “The landscapes were true; the people were real; the atmosphere was genuine,” wrote the curator Moussa Domit in his introduction to a 1978 retrospective of Douaihy’s work.15

But the paintings were conservative. They were pretty and lovely but also dull and suspiciously immutable, casting their subjects as unmodern and outside of history, internalizing the discourse of Orientalism. Douaihy’s early work captured none of the friction of the wider world, which was undergoing tremendous change. “At a time when Lebanon was gaining independence from French administration,” Domit explained, “and was trying to form a genuine image of itself—even while experiencing waves of socialist, communist, and religious ideologies that swept the country from both the East and the West—Douaihy was painting the valleys and the mountains and the villages and the ancient cities and the peasants: all that is most naïve.”16

It wasn’t until 1950, when Douaihy moved to New York, again with support from the Lebanese government, that he shifted decisively into the abstract idiom for which he is known. Prior to his departure, his work entered a period of transition. In the late 1940s, he began to break down his landscapes into blocks of color, some gestural and tempestuous, others flat and smooth. Throughout his life, Douaihy returned to the same sites, including the Bay of Jounieh, the Qadisha Valley, the monastery of Qannoubine, and the Mediterranean Sea. He spent months at a time in the village of Maaloula, one of the last places on earth to speak Aramaic as a living language. His views of Maaloula from the late 1940s are already semi-abstract, with grid-like clusters of horizontal rectangles stacked before sets of diagonal rectangles suggesting mountains and sky. By the 1950s, the same rectangles frame a mystical void (fig. 1). Douaihy’s nudes from this time are similarly geometric, with strong outlines, bold colors, and broad forms marking out equal values of body, drapery, and background.

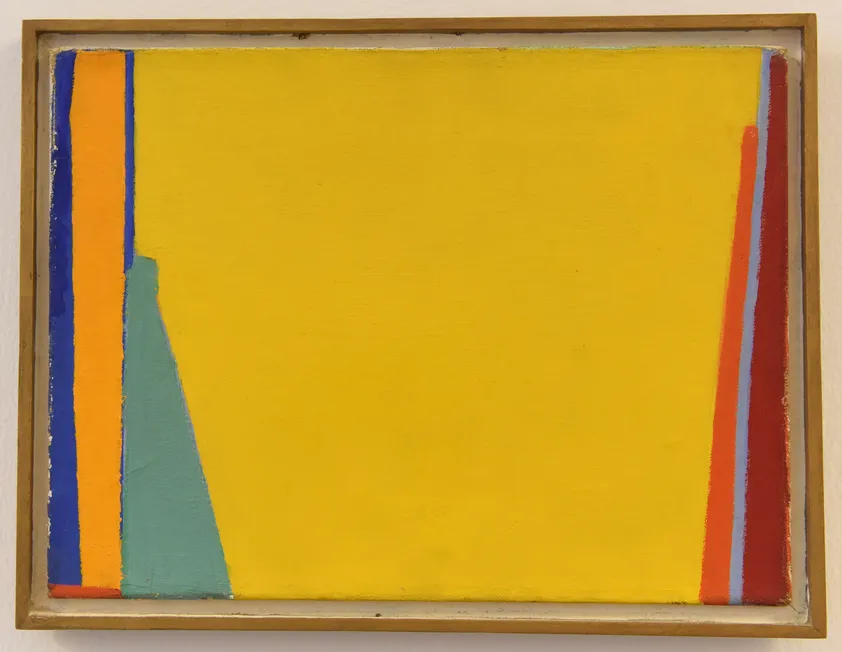

Douaihy thought of painting as creation itself, not as a faithful imitation of nature. His paintings were, if not acts of god, then at least transfers of divine power. In New York, the artist lived like a monk in the loft of a Maronite cathedral in Brooklyn Heights. He read philosophy and aesthetics, loved the work of Josef Albers, and puzzled over the soak-stains of Helen Frankenthaler.17 He began using acrylics, synthetic polymers, and epoxy. He made eye-popping color combinations. He developed a typology of horizontal compositions with wide expanses of color in the center, surrounded on either side by slivers, bends, curves, hooks, and angles of still more color (fig. 2). But his subjects remained defiantly the same.

Even in abstraction, Douaihy returned to the Lebanese landscapes he had known since childhood. The lines of his work traced out the same mountain crevices, elegant bays, and decisive Mediterranean coastlines. “I started to change the sea’s color from blue to red or yellow,” Douaihy explained. “That’s how far I’d go. The sky’s color was black or navy, and the earth’s color was different, too.”18 For the 1965 painting titled Diana, for example, the Mediterranean appears in the notched central panel as a wide expanse of green (fig. 3).

Douaihy’s international breakthrough came in 1966 with a solo exhibition at the Contemporaries Gallery on Madison Avenue. It was well reviewed, and Douaihy’s work caught the attention of collectors such as David Rockefeller. The Guggenheim Museum and the Grey Art Gallery each acquired a painting. Yusif Bedas, the high-flying Palestinian banker, bought another painting and donated it to the Museum of Modern Art, making Douaihy the first Lebanese artist to enter the museum’s collection.19 Majestic, an orange and brown abstraction from 1965, was loaned out twice—for a Guggenheim group show in 1967 and Douaihy’s North Carolina retrospective in 1978—but it has never been shown in the Museum of Modern Art itself.

Douaihy’s abstractions were linked not only to landscapes but also to Arabic letterforms and the Syriac script, which he used in the design of his first monograph.20 He made a series of paintings in the 1960s based on the Syriac alphabet. Later works paid tribute to Aramaic, including the explicitly calligraphic and geometric series known as “Amara,” where connected letterforms run horizontally, vertically, and diagonally, like Piet Mondrian’s Boogie-Woogie spoken in Douaihy’s language. Homage to Gibran, a perfectly square acrylic from 1975, takes the stems, bowls, and bellies of Arabic calligraphy and lays them over a strict, colorful grid. The effect is to suggest letters, and possibly sounds (alif, laam, haa, noun, meem) without forming clear words or phrases.

According to the publisher and archivist Badr El-Hage, who interviewed the artist extensively in the 1980s, Douaihy defined his work in relation to calligraphy and insisted that his art was only ever Middle Eastern, never French, never American. “I am in reality a Mediterranean artist,” he said.

The beauty of my [abstract painting] is that I have dispensed with classical curves. The simplification of space in my work is Arabic in nature, as in Arabic calligraphy. My works have come to contain a single expanse that is not three-dimensional … I have never seen anything more beautiful than Kufic calligraphy which finds its origins in the Syriac script … A single letter of the Arabic alphabet can become a great painting … on the condition that the artist knows how to get to the heart of the matter and produce his work with artistic precision.21

While critics in New York celebrated the arrival of fresh talent, critics in Beirut were initially appalled by Douaihy’s abstract turn. One story, possibly apocryphal, conveys the schism. Douaihy was close to Suleiman Frangieh, scion of a political family and Lebanon’s president in the early 1970s. Frangieh wanted to put a Douaihy painting in every Lebanese embassy around the world. Douaihy created a series of abstractions for this purpose and presented them to Frangieh. But Frangieh wanted the old work, not the new. He wanted nostalgic pictures of peasants and shepherds, paintings that would be easily understood as representations of the nation, even if what they offered was a fantasy, a naive vision of a country that never existed. Frangieh didn’t want challenging abstract paintings about “intensities of light” or “complementary values” or “inner motion” or the distinction among precision, hard edge abstraction, and geometry.22 Douaihy was so incensed that he refused to take back the rejected paintings, leaving them abandoned on Frangieh’s lawn.

The art historian Michel Fani argues that Douaihy’s move from the nostalgia of his early paintings to the boldness of his abstract work changed the history of Lebanese painting and did so specifically through the violence of his colors. Douaihy’s rupture, Fani writes, was neither rhetorical nor verbal but semantic.23 It changed how meaning was structured; it changed what the role of painting in Lebanon could be. It may have changed what abstract painting could do, the languages it could speak, as well. Douaihy was able to formulate solutions to the problem of painting after colonization, after independence, and in dialogue with the world by reaching back to a broader cultural heritage—one that was shared beyond national borders—to calligraphy, Arabic, and Aramaic. Though unstated as such, this was a response to the legacies of colonization, which involved, among so much else, the imposition of one language as superior to others.

Shafic Abboud: A Case Study on Abstraction as Storytelling and Mapmaking

An artist who came of age in the wake of Douaihy’s success, Shafic Abboud was born in 1926, in the Greek Orthodox village of Mhaydseh, in the hills east of Beirut. Abboud’s stomping ground was the neighborhood of Achrafieh, where he befriended the painters Georges Cyr and César Gemayel. Although he initially studied engineering, he soon turned his attention to art school instead.

The Académie Libanaise des Beaux-Arts, established in 1937, had been up and running for nearly a decade when Abboud arrived in 1946. Gemayel was the school’s director. Abboud’s classmates included Helen Khal, artist, critic, and founder of Gallery One, as well as the painter Yvette Achkar and the sculptor Michel Basbous.24 Abboud stayed for a year. Like Achkar and the artist Huguette Caland, he took lessons from the Italian painter Fernando Manetti, who specialized in frescos and came to Lebanon after studying religious art in Jerusalem.

Abboud’s earliest paintings were archetypal landscapes—parasol pines, red-roofed houses—in oil on wood or canvas. He learned to make lithographs and engravings, which he described at the time as erotic.25 Printmaking remained part of his practice for decades, alongside artist’s books, tapestries, ceramics, and the construction of sandouq al-firji, the wooden box with spools of pictures on paper that traveling storytellers would use to enchant their audiences. All of these artforms came from the cultures flowing in and through Lebanon. Abboud’s grandmother had been a village storyteller, and narrative was central even to his most abstract work to come. But in the years after independence, Abboud’s mind wandered. He dreamed of Paris, the energy of its art scene, the attention of its critics. Like his art school colleagues, he harbored “a fantasized vision of the French capital as an indispensable place of training.”26

In 1947, Abboud traveled to Paris with funding from his father and stayed for two years, until the money ran out. He returned to Beirut, then made his way back to Paris, via Alexandria, in 1951. Two years after that, Abboud landed a three-year scholarship from the Lebanese government, which allowed him to stay. He registered as an auditor at the École des Beaux-Arts. He attended studios in the neighborhood around the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, including the atelier of Fernand Léger and the atelier of the critic and cubist painter André Lhote. Eventually, Abboud rented a studio in the fourteenth arrondissement, next to Parc Montsouris, which figured into many of his paintings. He worked odd jobs and traveled extensively, back and forth to Beirut and circling around Europe.

Abboud threw himself into debates about geometric, lyrical, and gestural abstraction.27 His painting shifted, incrementally, from the compositions such as La Boîte à images, from 1952, which evoked folklore, pre-Islamic poetry, and the Levantine tradition of painting on glass, to abstract compositions that emerged from Abboud’s obsession with materials (he mixed all of his own colors and kept detailed notes on the different formulas he found to achieve certain textures) and from his tendency to work in layers, building up thick piles of paint with swirling brushstrokes. In the beginning, he rarely titled his paintings with anything more indicative than Composition. But this gradually yielded to series such as Les Pigeonniers d’Egypte (The Pigeon Houses of Egypt), 1963, carrying hints of figuration and drama, and Tu connais la mer? (You Know the Sea?), 1964, named for an exchange between the artist and his daughter.

Abboud’s first solo exhibition opened at Galerie de Beaune in 1955, the same year he began showing in the Salon des Réalités Nouvelles. He was the only Arab artist chosen to participate in the inaugural edition of the Paris Biennale, in 1959, though he complained bitterly of the racism against Arabs in France, and of his displeasure being treated as a foreigner. According to the curator and critic Pascale Le Thorel, in the years to come, Abboud was often selected for both local and international exhibitions, not as an outsider but as a representative of France and a proponent of School-of-Paris painting under the guise of lyrical abstraction.28

For the Paris Biennale, established by André Malraux and staged at the Musée d’art moderne, Abboud presented the second of his four Saisons, corresponding to the four seasons in monumental squares of oil on wood (fig. 4). Taken together, the Saisons are both a triumph of Abboud’s technique and achingly beautiful. Ranging from earth tones for fall and winter to rich greens for spring and deep blues for summer, they convey mood, memory, atmosphere, landscape, and weather in a balance of forms, colors, and textures. The standard line about Abboud is that he loved Pierre Bonnard but painted like Nicolas de Staël. This comparison is wonderful but misses something crucial about the spatial and intellectual depths of Abboud’s paintings. They look like aerial maps, charting places that exist not in front of him but in his mind (or in ours, as viewers). The fullest expression of this, of Abboud’s abstraction as both storytelling and mapmaking, appears in the triptych Une vie singulière, from 1969. The three panels present two opposing forces of red and green on either side of a boisterous knot. That knot is the exact shape of the promontory of Beirut.

Of all the Lebanese artists who lived in postwar France, Michel Fani writes that Abboud was the most complex, and his experience of the Paris-Beirut relationship was the most painful. His many departures and returns caused internalized violence and inner conflict.29 In Fani’s formulations, Abboud expressed all of this linguistically through his paintings. “Abboud wants the abstract as language.”30 He was an impressionist who used cubism for speaking, a storyteller who used abstraction to narrate.31

Despite his success in Paris, or perhaps because of it, Abboud returned to Beirut every year to teach for three months. His studio classes were part of the Lebanese University’s Institute of Fine Arts, a large and eternally underfunded public institution, where Abboud made a point of conducting his lessons in Arabic. In the notes he made for his students, he wrote: “Obviously, in order to paint, one MUST ALWAYS PAINT SOMETHING. Thus: a subject. A subject is the nexus between a fact, a character, an object, and a coloured vision, a sort of formatting suggested as through a lightning flash lighting up a landscape for an instant.”32

Abboud submitted his work to the annual Salon d’automne, a hallmark of Beirut’s Sursock Museum. His painting Enfantine (Child’s Play), a large-scale, majestic composition with pools of blue and fields of pink crowding into squares of purple and crimson, won the salon’s grand prize in 1964 (fig. 5). This precipitated a crisis among local critics over the purported elitism of abstraction in modern art. According to the curator Sylvia Agémian, the debate was so loud, chaotic, and severe that the museum had to shutter its gates. With Abboud building on the momentum of Douaihy’s rupture, “the door to abstract art had been opened,” Agémian recalled.33

In 1966, the Lebanese poet Saleh Stétié, in a review of that year’s Salon d’automne, described Abboud as the Don Quixote of Lebanon who had conquered Paris fifteen years earlier.34 Stétié wrote of Abboud’s paintings:

They all suggest, by the powerful articulation of their rhythms, by the violent intermingling of broad and abrupt strokes, by their warm and precious tonalities, the presence of a powerful outside personality, inspired and abundantly lyrical. Some of our painters have at times reproached Shafic Abboud, who is so outstandingly gifted, for giving up his traditional Oriental heritage in order to express himself in the international language of today’s art. Abboud does this with such an accent, his visual expression is so straightforward, that his originality remains manifest even on the level of an uprooted language.35

Abboud was living the full cultural life of two cities at the same time. Beirut was heading into its golden age just as Paris, renowned as the capital of world culture and center of the international avant-garde, was ceding that position to New York. Abboud suffered the arrival of pop art and the talk of crises in painting.36 He said he was no longer Lebanese and had not yet become French. His nationality was that of a foreigner.37 Although he retracted his first application for French citizenship in the aftermath of the war in 1967, a staggering defeat for the Arab world, he was naturalized two years later, in 1969. With breathtaking clarity, he told the art critic Nazih Khater, in 1975: “The principle of a return to heritage as a political move is highly important, because it attests to a rejection of cultural colonization.”38 Abboud returned to Beirut as often as he could, staying for as long as possible, until 1978, three years into Lebanon’s civil war. For the next two decades he remained in Paris, wrestling with distance as with depictions of color and light (fig. 6).

![Abboud, Shafic. <i>Les amours et les jeux </i>(Love and Games)<i> </i>[diptych]. 1979. Oil on canvas. 146 x 88.5 cm. Sursock Museum, Beirut. Gifted by Brigitte Schehadé, 1983. Image courtesy of the Sursock Museum Collection, Beirut.](https://bop.unibe.ch/manazir/article/download/11590/version/11889/15153/57659/ncyvxfrlfbiu.webp)

Saloua Raouda Choucair: A Case Study on Abstraction as Poetry and Islamic Geometry

While Abboud suffered the experience of exile, Saloua Raouda Choucair took her foreign travels in stride. She was born in Beirut to a wealthy Druze family in 1916. Her father was drafted into the Ottoman army and died almost immediately of typhus in Damascus. Her mother raised three children on her own. Choucair went to Ahliah, a progressive school for girls in the old Jewish quarter of Wadi Abou Jamil, graduating in 1932. She drew caricatures for the school newspaper and tagged along with her sister to Saturday art classes at the American University of Beirut (AUB). In 1933, Choucair spent a year learning French at the French Secular School in Beirut. Her earliest paintings date from a few years later.39

In 1937, Choucair’s family left Lebanon for Iraq because of visa problems pertaining to her brother. Fresh out of university, she taught science and drawing at an elementary school in Kirkuk. By 1942, Choucair had returned to Beirut and was taking lessons from the artist Omar Onsi. With Lebanon on the verge of independence, in 1943, Choucair left the country again and stayed for seven months in Egypt. She had hoped to visit the fine art museums of Cairo and Alexandria but found them closed due to World War II. Choucair explored mosques and monuments instead. Photographs from her travels show her smiling on the steps of the Pyramids and at the base of the Sphinx.40 Details of Pharaonic monuments and Islamic architecture made their way repeatedly into Choucair’s art.

Back in Beirut, Choucair took a job as a librarian at AUB in 1945. She audited courses in philosophy, history, and Arabic literature. With a group of students from the medical school, she created the AUB Art Club, precursor to the storied AUB Art Department, which was established by the artist Maryette Charlton in 1952. The Art Club, whose meetings took place around Choucair’s desk in Jafet Library, invited Onsi and Moustafa Farroukh to give public lectures and drawing lessons. Douaihy did the same, setting up his equipment and executing a painting from start to finish in one session.41

In 1947, the year Abboud traveled to Paris, Choucair staged her first exhibition at the Arab Cultural Club, on Abdel Aziz Street in Hamra. She presented a series of gouaches, all geometric abstractions. The show was improvised when another event that Choucair had lined up for the club fell through. As such, there is no record of it taking place—no invitation card, no checklist —but in the 1970s, Choucair periodized her work in a chronological list, including ten oil paintings and six gouaches from 1946.42

One such gouache, untitled but signed and dated 1946, is a diminutive tangle of colorful geometric forms. An arm of bright magenta reaches in from the left to wrap around bends of dark hunter green, vivacious lime, and deep blue, with bolder, more angular stretches of black and gold running up and down the right. The lime green shape in particular bears a passing resemblance to the Arabic letter haa, turned on its side. The dark green and magenta shapes also suggest the tails, curves, and bellies of Arabic letters. Most prominent, however, is the complexity with which the shapes fit together, like a puzzle, and how they repeat certain moves, with subtle variations and rotations.

Another geometric abstraction, the oil painting Ya layl (Oh Night), from 1947, features a shape like the Arabic letter waw, flipped, repeated in shades of blue and purple, and arranged in three clusters alongside another shape like the teeth of the Arabic letter seen or sheen.43 But the letters are illegible as such, leaving their meaning open to interpretation. The untitled gouache from 1946, for example, could just as easily be a landscape with trees and buildings, the gold standing in for the incomparable Ras Beirut sunset. Another shape, resembling both a mosque with a minaret and the letters meem and alif, like the interrogative Arabic noun for “what,” recurs across four decades of Choucair’s work, including an early gouache (1946–47), a terracotta sculpture (1983–85), and an oil painting, Fractional Module (1947–51) (fig. 7).

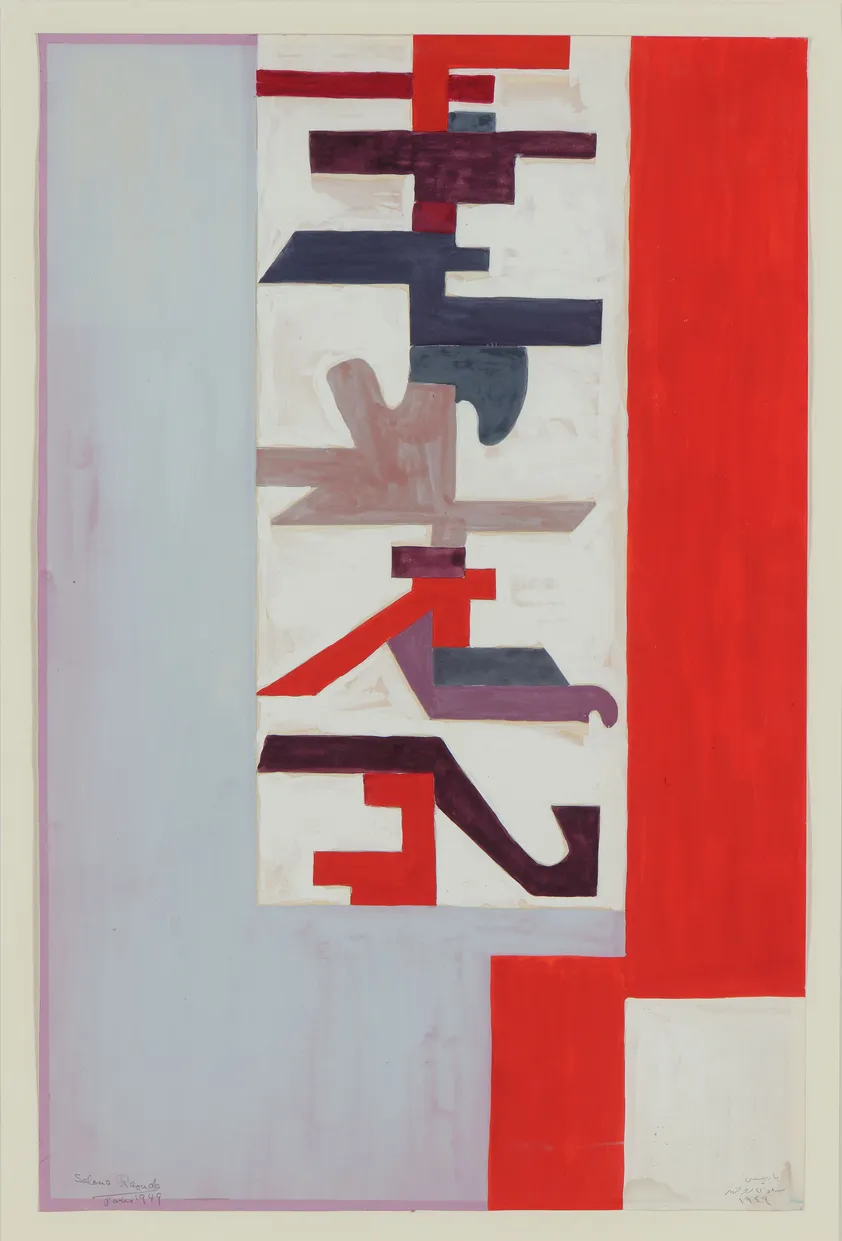

According to the notes she kept in her studio, Choucair was experimenting with Arabic calligraphy as early as 1946.44 A self-portrait from 1947, in oil on Masonite, shows the artist’s name circling her head in stylized script. A pair of gouaches titled Experiment with Calligraphy, from 1949, echo the possibility of letter forms (fig. 8). Here, the letters, if indeed they are letters, run vertically rather than horizontally. The central forms stack up and down rather than side by side. More than anything, they prefigure Choucair’s sculptures from the 1950s and 60s.

In conversation with Helen Khal, Choucair stressed that her geometric abstract work began “with the square, the circle, and the triangle” and was rooted, by necessity, in the mathematical rhythm of Arab art.45 Compared to Douaihy and Abboud, Choucair was unmoved by the lyrical tradition of Lebanese landscape painting. She arrived at abstraction through Sufism, descriptions of heaven in the Quran, and the pre-Islamic poetry of Antarah Ibn Shaddad. Abstraction for her was a process of distillation and purification, “the Arabs’ quest for the essence and the abstract.”46 According to Khal, it was Choucair’s indignation over a philosophy professor who told her the Arabs had no art at all that pushed her to study Islamic art and then, to make her own art from what she learned in order to prove him wrong.47 What prompted Choucair to become an artist, then, was not her encounter with modernism in Paris but rather her anger in response to the colonial encounter in Beirut.

Choucair traveled to Paris in 1948. She accompanied her brother-in-law, a former cabinet minister, on a business trip and decided to stay. She realized she could live for a month in the student dormitories of the Cité universitaire for the same amount she was paying for lunch at the Hotel Normandie.48 In three years, Choucair attended three, possibly four different art schools and studios, including Léger’s atelier. Unsatisfied, she defected from Léger and helped the artists Jean Dewasne and Edgard Pillet set up the Atelier de l’art abstrait.49

Inspired by the Bauhaus, the atelier followed a workshop model where experiments were collective and shared. From her peers, Choucair pulled different elements into her formal language and in doing so, enlarged her vocabulary. In 1951, she had a gallery exhibition at Colette Allendy, which included some of the same work she had shown in Beirut. Abboud reviewed her show for the newspaper L’Orient, crediting Choucair for finding in abstract painting the elements of a universal language.50 Like Douaihy and Abboud, Choucair participated in the Salon des Réalités Nouvelles and later, the Salon de mai.

And then she went home. Choucair married the journalist Youssef Choucair in 1953. They had a daughter four years later. From 1952 until 1956, Choucair worked for the US government via for the Point Four Program, part of the Truman administration’s attempt to win the Cold War through soft power, technical assistance, and support for craft economies in the developing world. Choucair learned ceramics, enameling, and jewelry design and toured factories and craft schools in the United Sates.51

Although Point Four was ultimately deemed a failure of so-called modernization from below, Choucair’s experience with the program signaled a major pivot in her career, inspired, perhaps, by its focus on useful objects and women’s economic empowerment.52 “The world is changing rapidly,” she said at the time, “and we must change with it.”53 In 1957, Choucair shifted definitively from painting to sculpture, translating the forms of her early gouaches into fiberglass, wood, metal, and stone.54

Initially grouped under the titles “Poems” and “Odes,” her first sculptures convey units of Arabic poetry. Compared to her Experiments with Calligraphy, the shapes are similarly stacked and vertical but here they are modular. Each piece represents a verse or bayt in Arabic poetry. Whether arranged in a column or nestled into a row or a cube, the pieces are meant to be taken apart and reassembled. Each variation creates new meaning, yet the meaning of each piece remains complete. Another series, “Trajectories of a Line,” revives Choucair’s run-in with ancient Egyptian monuments. Trajectory of a Line (The Pharaonic), from 1957–59, for example, is totally abstract but projects the presence of a regal standing figure (fig. 9). Another series, known as “Duals,” from the 1960s and 70s, consists of ruminative, interlocking forms, always in pairs, which have been variously read as lovers, peace between warring factions, and the oneness of god.

When the critic Joseph Tarrab reviewed the Sursock Museum’s Salon d’automne in 1982, he singled out Choucair for the passion, brio, and warmth of her sculptures. They invited viewers to play a game, to imagine the infinite permutations and transformations of their modular, variable parts. This placed the sculptures “at the cutting edge of modernity while referring, paradoxically, to the profound essence of Arab-Muslim art.” In Tarrab’s view, they were the only works “to plant their roots in the most authentic eastern tradition and in the best lived contemporaneity.”55

A year later, Choucair produced her first public sculpture. Installed on a roundabout in Ramlet El-Baida, draped in a white veil, and nicknamed “the Bride of Beirut,” the piece consisted of five parts stacked like one of her poems.56 In response, the artist and critic Samir Sayegh described Choucair as matchless in her vision, an artist strong enough to whip everything around her into the movement of her sculpture, which was also the elevation of the divine.57 The differences are striking between these critiques, which are also critiques of colonialism. Where Tarrab noted opposition between modernity and authenticity, Sayegh found coexistence in the mixed-up cosmopolitanism of Beirut.

Cosmopolitan Returns (Conclusion)

Cosmopolitanism, as Martha Nussbaum reminds us, really is as old as the Greeks. When asked where he came from, Diogenes the Cynic said he was a citizen of the world. He didn’t name a lineage, geography, gender, or social class, but rather what he shared with humanity. “Cynic/stoic cosmopolitanism urges us to recognize the equal, and unconditional, worth of all human beings.”58 The cosmopolitan tradition has limitations, as Nussbaum elaborates, most notably its disregard for non-human life and nature. But the grounding of cosmopolitanism in dignity and equality makes it especially useful for reformulating modernism as global.

The artist and theorist Rasheed Araeen landed on this same idea of equality in his argument for the importance of Islamic geometry (as an art form and a system of abstract thought) and against its obliteration from historical narratives linking Greek rationality to the Renaissance. For Araeen, the same geometry that originated in the twelfth century and inspired Choucair remains accessible as a tool for meditation, imagination, and translation (of revealed knowledge into everyday life), and as a much-needed allegory for human equality.59

That said, it was Stalin, and before him Hitler, who thoroughly corrupted the idea (and ideals) of cosmopolitanism by turning it into an anti-Semitic slur.60 A rehabilitation of cosmopolitanism and its complex relationship to globalization has been ongoing since the 1990s—effectively the same period in which art historians have been theorizing global modernism. Prominent among them, Partha Mitter uses cosmopolitanism as a generative alternative to the politics of stylistic influence. “As a category,” Mitter writes, “influence ignores more significant aspects of cultural encounters, the enriching value of the cross-fertilization of cultures that has nourished societies since time immemorial.”61 Such encounters define cosmopolitanism, and in Mitter’s view, together with serious scholarly attention to local and regional contexts, make it possible to restore artists’ agency and decenter the canon.

In Cosmopolitanism: Ethics in a World of Strangers, Kwame Anthony Appiah defends cosmopolitanism as contamination. This is instructive for recalibrating the relationship between Paris and Beirut because, in Appiah’s view, it is migration above all that brings cosmopolitanism into being. He quotes the novelist Salman Rushdie: “Mélange, hotchpotch, a bit of this and a bit of that is how newness enters the world.”62 Appiah’s vivid set piece for cosmopolitan contamination is the Asante capital of Kumasi in Ghana—multi-ethnic and multilingual, connected among other things to globalized commodities, ancient trade routes, and the pilgrimage to Mecca.63

Along similar lines, Kobena Mercer uses cosmopolitanism as a conceptual tool for returning to the work of twentieth-century artists who were dismissed as minor because they lived on the wrong end of the metropolitan-colonial matrix.64 Mercer asks if a reconfigured understanding of cosmopolitanism can help to sort through ideas about chronology and artistic agency and rework art historical genres such as the case study, the monograph, and the survey, accommodating complex layers of cultural difference. He draws on the work of the anthropologist James Clifford to define cosmopolitanism as discrepant, as “cosmopolitanism-from-below.”65

Douaihy, Abboud, and Choucair all “spoke” abstraction with different accents. Abstraction in their work coexisted with landscape painting, religious painting, references to calligraphy and Aramaic and Syriac; with storytelling, mapmaking, memory, nostalgia, and longing; with Arabic letterforms, units of poetry, principles of Sufism, scientific concepts, geometry, and more. “What is present in the novel,” writes Bakhtin on heteroglossia, “is an artistic system of languages, or more accurately a system of images of languages.”66 Arguing against the notion of a unified style or voice, as against an ordering or distilling analysis, Bakhtin insisted that novels included a huge range of languages, dialects, patterns of speech, and expressions. Each language was stratified, and no language was singular. The meaning of the novel was therefore always open and ever-changing. The same can be said for the work of Douaihy, Abboud, and Choucair. Their orchestrating language may be Arabic, but in varied forms and in dialogue with so much else. To read their work as derivative or imitative or belated in relation to western modernism makes no sense because western modernism is already there, making noise and talking loudly in their work. The signs, shapes, and textures of their paintings and sculptures demand more than comparison based on isolated, already familiar elements.

“There is no way to practice a canon-free art history,” warns the art historian Steven Nelson.67 The promise of global modernism, as a methodology, is to address the problem of the many missing others of art history, including women, people of color, and populations outside of Western Europe and North America, by taking apart the narratives and structures that have long enforced their exclusion. To level Paris and approach it as one in a network of cities, here connected to and in dialogue with Beirut, is one way of putting global modernism into practice. Breaking the canon and figuring out what to do with its pieces is another. It is not enough to add Douaihy, Abboud, and Choucair to an existing canon as lone, isolated geniuses. Nor is it enough to build around them separate, parallel, plural, or alternative modernisms.

Rethinking the art historical narrative demands redefining concepts like cosmopolitanism and looking anew at the relationship between linguistic phenomena and the visual arts. One way to break or at least disturb the canon might be to stuff it so full of irreducible case studies that it cracks and buckles. Another might be to treat such case studies as worlds as vibrant, chaotic, stratified, heteroglot, and impossible to order as Bakhtin’s heteroglossic novel, laying out the vast amounts of work to be done to understand them. It will be crucial not only to reconfigure the western canon but also to revisit Lebanon’s national canon, as the latter was clearly made in the mirror image of the former. Existing accounts of Douaihy, Abboud, and Choucair may need their own revision to see what they themselves have obscured and excluded.

Bibliography

Abboud, Shafic. “L’exposition Salwa Rawda: Paris révèle la peinture abstraite d’une jeune Libanaise.” L’Orient. 20 May 1951.

Appiah, Kwame Anthony. Cosmopolitanism: Ethics in a World of Strangers. New York and London: W. W. Norton & Company, 2006.

Araeen, Rasheed. “Preliminary Notes for the Understanding of the Historical Significance of Geometry in Arab/Islamic Thought, and Its Suppressed Role in the Genealogy of World History.” Third Text 24, no. 5 (2010): 509–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/09528822.2010.502770.

Bakhtin, Mikhail M. “Discourse in the Novel.” In The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays. Translated by Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist, edited by Michael Holquist. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1981.

“Brief History of the AUB Art Club,” 1952. Fine Arts and Art History Collection (FAAH), 1952–present. Archives and Special Collections, Jafet Library, American University of Beirut.

Chammas, Carla, Rachel Dedman, and Omar Kholeif, eds. Helen Khal: Gallery One and Beirut in the 1960s. London: Sternberg Press, 2023.

Choucair, Saloua Raouda. “How the Arab Understood Visual Art.” Translated by Kirsten Scheid. In Modern Arab Art: Primary Documents, edited by Anneka Lenssen, Sarah Rogers, and Nada Shabout, 145–49. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2018. Originally published as “Kayfa Fahima al-‘Arabi Fann al-Taswir,” Al-Abhath 4, no. 2 (June 1951): 190–201.

⸻. Artist’s file, Salwa Mikdadi Papers, Archives and Special Collections, New York University Abu Dhabi Library, New York University, Abu Dhabi.

⸻. Artist’s file. Sursock Museum Library and Archives, Sursock Museum, Beirut.

⸻. Archives of the Saloua Raouda Choucair Foundation, Ras El-Metn, Lebanon.

Dagher, Charbel. Arabic Hurufiyya: Art and Identity. Translated by Samir Mahmoud. Milan: Skira, 2016.

Dib, Kamal. Warlords and Merchants: The Lebanese Business and Political Establishment. Reading: Ithaca Press, 2004.

Domit, Moussa. The Art of Saliba Douaihy: A Retrospective Exhibition. Raleigh: North Carolina Museum of Art, 1978.

Douaihy, Saliba. Artist’s file. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1966. [Updated in 1978.]

Drugeon, Fanny. “Paris cosmopolite? Artistes étrangers à Paris, parcours 1945–1989.” In La construction des patrimoines en question(s): Contextes, acteurs, processus, edited by Jean-Philippe Garic, 161–181. Paris: Éditions de la Sorbonne, 2015.

El-Hage, Badr. “Autobiography and Artistic Views: Saliba Douaihy.” In Forever Now: Five Anecdotes from the Permanent Collection, edited by Nada Shabout, 51–70. Doha: Bloomsbury Qatar Foundation, 2012.

Fani, Michel. Dictionnaire de la Peinture au Liban. Saint-Didier: Éditions de l’Escalier, 1998.

Faris, L. Leila. “Raouda Has Faith in Abstract Art.” Outlook, 31 January 1953, 3.

Gelbin, Cathy S., and Sander L. Gilman. Cosmopolitanisms and the Jews. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2017.

Houssais, Coline. Paris en lettres arabes. Paris: Sinbad/Actes Sud, 2024.

Joyeux-Prunel, Béatrice. “Toujours Ailleurs: Portrait de l’artiste parisien en migrant, et de Paris en centre périphérique.” In Paris et nulle part ailleurs: 24 artistes étrangers à Paris, 1945–1972, edited by Jean-Paul Ameline, 74–89. Paris: Éditions Hermann, 2022.

Kassir, Samir. Beirut. Translated by M. B. DeBevoise. Berkeley, Los Angeles and London: University of California Press, 2010.

Khal, Helen. “The Art of Saloua Choucair.” Arab Perspectives, March 1985, 26–31.

⸻. The Woman Artist in Lebanon. Beirut: Institute for Women’s Studies in the Arab World, 1988.

Lahoud, Edouard. L’Art Contemporain au Liban. Beirut: Dar el-Machreq Éditeurs, 1974.

LaTeef, Nelda. Women of Lebanon: Interviews with Champions for Peace. Jefferson, NC, and London: McFarland, 1997.

Lemand, Claude, ed. Shafic Abboud. Paris: Galerie Claude Lemand and Éditions Clea, 2006.

Le Thorel, Pascal. Shafic Abboud. Milan: Skira, 2014.

Maasri, Zeina. Cosmopolitan Radicalism: The Visual Politics of Beirut’s Golden Sixties. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020.

Meier, Prita. “Authenticity and Its Modernist Discontents: The Colonial Encounter and African and Middle Eastern Art History.” The Arab Studies Journal 18, no. 1 (Spring 2010): 12–45.

Mercer, Kobena, ed. Cosmopolitan Modernisms. Cambridge, MA and London: The MIT Press, 2005.

Mitter, Partha. “Collapsing Certainties: Reflections on the End of the History of Art.” The Cairo Review of Global Affairs 14 (Summer 2014): 38–47.

Najem, Tom. Lebanon: The Politics of a Penetrated Economy. Abingdon: Routledge, 2012.

Nelson, Steven. “Turning Green Into Black, or How I Learned to Live with the Canon.” In Making Art History: A Changing Discipline and Its Institutions, edited by Elizabeth C. Mansfield, 54–66. New York and London: Routledge, 2007.

Nussbaum, Martha C. The Cosmopolitan Tradition: A Noble but Flawed Ideal. Cambridge, MA and London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2019.

Pedrosa, Adriano. “History, Histórias.” In Afro-Atlantic Histories, edited by Adriano Pedrosa and Tomás Toledo. New York: DelMonico Books, 2022.

Sader, P. Jean. The Art of Saliba Douaihy. Beirut: Fine Arts Publishing, 2015.

Sayegh, Samir. “Tamayyuz uslub wa faruda ru’ya’,” Al-Kifah Al-Arabi, 25 July 1983, 70–71.

Scheid, Kirsten L. Fantasmic Objects: Art and Sociality in Lebanon, 1920–1950. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2022.

⸻. “Painters, Picture-Makers, and Lebanon: Ambiguous Identities in an Unsettled State.” PhD diss., Princeton University, 2005.

Stétié, Salah. “Salon d’automne.” L’Orient littéraires, 1966.

Tarrab, Joseph. “Le Salone d’automne au Musée Sursock: La Sculpture.” L’Orient-Le Jour, 28 December 1982, 17.