The paper examines the development of art galleries and exhibition spaces in Lebanon since the beginning of the civil war in 1975 and throughout the 1980s, with a particular interest in the shifts and changes that occurred as a result of the hostilities. This includes the dissolution of Beirut as an artistic centre and the gradual decentring of spaces and activities outside the capital. While the focus is on the decade of the 1980s, the analysis will look at developments that began earlier in order to contextualize them. One gallery in particular, Galerie Damo, will be examined in detail, including its founding history, mission, and exhibition programme. The gallery began operating after the first phase of the civil war in 1977 and serves as an example of exhibition activity outside the capital. It relied largely on artists who had exhibited extensively in various art galleries, cultural centres, and other spaces in Beirut before the war, and is therefore well suited to analysing the ruptures that occurred after 1975, as well as possible continuities.

Lebanon, Art History, Art Galleries, War, Exhibitions

This article was received on 26 September 2024, double-blind peer-reviewed, and published on 17 December 2025 as part of Manazir Journal vol. 7 (2025): “Defying the Violence: Lebanon’s Visual Arts in the 1980s” edited by Nadia von Maltzahn.

This contribution aims to look at some of the transformations within the artistic scene triggered by the Lebanese Civil War (1975–90). Despite the state of emergency and the resulting unpredictability of events, exhibitions continued to take place during this fifteen-year period, although at a different rhythm and in often different settings than before. A comprehensive and nuanced picture of this time, that examines continuities, ruptures, transformations, and possibly new beginnings, will help us to ultimately connect these exhibition practices to prewar and postwar artistic activities rather than view them as separate developments. The article will examine the setting, role, and activities of Galerie Damo in greater detail, with the aim of providing an illustrative example of the 1980s that started in 1977, in the aftermath of the first phase of the war. Galerie Damo’s portfolio primarily comprised artists who had been active in the decades preceding the war and who were largely considered part of the established Lebanese artistic canon. The gallery and its programme are therefore suitable for an analysis of artistic continuities in times of radical rupture. While focusing on the continuities regarding the choice of artists, the analysis also identifies potential shifts in the artistic approaches and themes pursued by individual artists that may be related to the war context. Furthermore, this article seeks to establish connections between the initiatives introduced by Galerie Damo, particularly those pertaining to the gallery system and art market, and those initiated by seminal galleries such as Gallery One and Contact Art Gallery. This approach allows for a comprehensive examination of developments that commenced during the 1960s and 1970s.

Prior to the war, Beirut was emblematic of openness, fluidity, and sense of experimentation.1 The city succeeded in attracting artists, intellectuals, writers, thinkers, and activists from other Arab countries and internationally. As Kamal Boullata noted, “Beirut’s brand of openness created the ideal environment for becoming a microcosm of the Arab world, embracing all its distinctions and contradictions.”2 It boasted a significant concentration of artists, intellectuals, writers, and art lovers, coupled with a proliferating network of cultural outlets, periodicals, and galleries that not only disseminated these ideas but also facilitated their exchange. Consequently, Beirut served as “a nexus of transnational Arab artistic encounter, aesthetic experimentation, intellectual debate and political contestation.”3 Cultural life in Beirut was at its peak. In his analysis, art critic Joseph Tarrab (1943–2024) likened Beirut to a “galaxy.”4

The city hosted an array of art galleries, especially in Ras Beirut and the area around Hamra. In addition, there were numerous cultural centres and clubs, modern hotels, restaurants, cafés, and others, all of which regularly hosted art exhibitions.5 Among the most important galleries in terms of vision and outreach were Gallery One, established by Helen Khal (1923–2009) and Yusuf al-Khal (1917–87) in 1963, and Contact Art Gallery, founded by Waddah Faris (1940–2024), César Nammour (1937–2021), and Mireille Tabet (1939–2022) in 1972. Both galleries shared an interest in introducing the public to new (Arab) artists, styles, and in broadening the artistic canon across the Arab region. In this capacity, they played a pioneering role, making a significant contribution to the emergence of Beirut as a centre for the artistic avant-garde in the Arab region. Together with the other galleries and spaces, they constituted a dense network of artistic activities.

With the outbreak of civil war, cultural life came to a near standstill, with few, if any, possibilities for artists to exhibit their work. The so-called “Battle of the Hotels,” which occurred during the early phase of the armed conflict, had a particularly detrimental impact on the area of Minet al-Hosn and the adjacent neighbourhoods of Clémenceau, Ain al-Mraisseh, Zokak al-Blat, and Hamra, where most galleries were located. Many galleries closed for good, while some relocated to other regions or abroad.6

By the end of 1976, what was known as the “two-year-war” seemed to be over, and some spaces, including the foreign cultural centres and cultural clubs, resumed their activities. However, this process was gradual and hesitant, as evidenced by a magazine article titled “The galleries are absent and the visual arts occupy new spaces” from November 1977.7 Its author expressed regret that almost no former art galleries had reopened, despite the readiness of artists to exhibit. He considered art to be a “national necessity” (darura wataniyya) at this juncture and therefore urged gallery owners to reopen their spaces without delay if they were to facilitate the revival of the artistic movement. Of the galleries referenced in the article, only Contact Art Gallery resumed its activities, in December 1977. The gallery, then managed by César Nammour and Mireille Tabet alone, organized three exhibitions8 before being forced to close permanently due to the resumption of hostilities.

In these challenging times, new initiatives and spaces were emerging in Beirut, including Galerie d’art Bekhazi (GAB Center) in Ashrafieh, which was founded by Nader, Souheila, and Georges Bekhazi (1977), Galerie Rencontre by Antoine and Michel Fani in Watwat (1979), Galerie Trait d’Union–Maisons Fleuries by Raymond Chouity in Ashrafieh (1980), Galerie Platform by Samia Tutunji (1984), and al-Muntada initiated by Mohammad Barakat and run by Faeqa Owaida in Clémenceau (ca. 1984).9 Two venues run by George Zeenny (1943–2015) also regularly organized exhibitions: the restaurant Smugglers’ Inn on Makhoul Street, which had become a refuge for artists and writers during the war (ca. 1977), and, in close proximity, the Planula Elissar Visual Art Center on Bliss Street (1980). Zeenny was instrumental in creating opportunities for artists to exhibit their work and meet. In January 1984, for instance, he initiated weekly meetings among artists at the Planula Elissar Visual Art Center. He also organized group exhibitions featuring both emerging and established artists.10 On the same street, Lebanon’s first diner, Uncle Sam’s, founded in 1960, reopened in 1981 with a new formula that allowed for artistic events such as exhibitions.11 Among the former hotel galleries, only the Carlton Hotel in Raoucheh continued to organize exhibitions, along with the newly established and nearby Summerland Hotel.12 In 1980, the Hôtel Alexandre in Ashrafieh emerged as an exhibition space too, but mainly, it seems, as an extension of the activities of Galerie Chahine. Other venues included the gallery of the National Council of Tourism (CNT) in Hamra (also known as Salle de verre), which held regular exhibitions throughout the 1980s, the Goethe-Institut in Bliss Street, the private residence of Samia Tutunji next to the National Museum,13 and other, sometimes improvised spaces.14

One of the galleries taking up the challenge to show art in war-time Beirut was Galerie Épreuve d’artiste, founded by Amal Traboulsi (b. 1943) and Martin Giesen (b. 1945) in 1979. It was situated in the Clémenceau area in Ras Beirut. It was the first gallery in Lebanon dedicated to graphic art and contemporary prints, and unlike most new galleries, it did not open outside the Hamra area, but in the middle of it. In an interview, Amal Traboulsi elucidated the rationale behind the establishment of the gallery:

Some of the Lebanese artists stopped creating, the war was too heavy for their sensitive nature. The opening of a new gallery in those times was a breath of fresh air which gave them some hope (because most galleries were closed), and they started to create again. It was very interesting. But it was not always the best of each artist’s work. War was not really something that gave them motivation. […] We wanted to specialize in the techniques of printmaking such as etching, lithography, woodcut, linocut, and silkscreen. It was what we liked very much. But it didn’t work out really well because what was done in the West did not interest the Lebanese at that time. They felt a big gap between their emotions and the rigid concept of the contemporary western art.15

Opening an art gallery in Clémenceau in the middle of the war meant claiming back normality. Artistic practice was often regarded as an act of hope and a means of resisting the war as evidenced by the newspaper article “Continuing for an art-hungry audience” in which gallery owners reported that sales had almost ceased, but that they were willing to continue.16 Exhibition openings were also an occasion to meet and exchange, something that had become rare during those years. However, the gallery was compelled to adapt to the prevailing local circumstances and reposition its profile accordingly. During periods of relative calm, Galerie Épreuve d’artiste frequently invited artists from abroad. Such occasions provided a valuable opportunity for artists to engage in discourse and exchange ideas about their work. Amal Traboulsi points out that, contrary to what one might assume, artistic activity was quite vibrant during the 1980s “as Beirut remained the capital of Arab art despite the war and the opening of the Emirates to the art world.”17

A newspaper article on the occasion of Noff al-Hadi’s exhibition at the Summerland Hotel in Beirut and Sami Abou Kheir’s exhibition at the Casino du Liban in Maameltein in June 1980,18 whose tone is almost too enthusiastic when contrasted with Joseph Tarrab’s statements on the declining situation of art during the war, testifies not only to the continuation of artistic activity, but also to its effervescence: “There is no denying that painting in Lebanon is doing well, very well indeed. Not a week goes by without at least one or two vernissages.”19 The frequency of exhibitions depended on the phases of the war and could sometimes be more intense than in other years. It was also connected to the location of the venues.

Despite these new beginnings, the intellectual fabric and enriching diversity of Beirut’s pre-1975 art scene had disintegrated. According to Joseph Tarrab, not only was the infrastructure heavily damaged, but more importantly, so too were the social and intellectual ties.20 Nevertheless, Beirut retained its status as a cultural centre or as the “metropolis of Arab modernity,” in Kamal Boullata’s words, until 1982, the year of the Israeli invasion of Lebanon and the withdrawal of the PLO, which marked the end of Beirut’s pivotal role in the formation of modern Arab culture.21 This correlates with increased migration from the capital to the suburbs after 1982, linked to the deterioration of the political situation.

Outside the capital, in the suburban areas to the north, Galerie Damo in Antelias was the first gallery to open in 1977. In 1982, Yusuf al-Khal relaunched Gallery One in collaboration with architect and urbanist Riad Tabet, near the highway in Zalka and close to Antelias.22 It existed only until 1983 and did not reach the same level of activity and outreach as previously. Among the few activities were individual exhibitions by Alfred Basbous and Michel Akl in 1982, and by Georges Akl and Jean Khalifé in 1983. The former space for the Arab avant-garde that had been a galaxy of its own was now entirely isolated from its former networks, neighbourhoods, and publics.

Additionally, a novel phenomenon emerged, whereby galleries established spaces in the recently constructed beach resorts situated along the coast between Beirut and Jounieh. Galerie Chahine by Richard Chahine, while maintaining its branch in Beirut’s quarter of Verdun, opened a new space at the “Solemar” beach resort in Kaslik in 1984. In 1983, Galerie La Toile by Alexa Bourji opened at the “Rimal” resort in Zouk Mosbeh, and around 1987, César Nammour, who had previously served as the co-director of Contact Art Gallery, inaugurated Galerie Les Cimaises at the “Holiday Beach” resort in Nahr al-Kalb. Galerie Épreuve d’artiste relocated from Beirut to Kaslik in 1986, and Galerie Alwane by Odile Mazloum, the proprietor of the previous Galerie L’Amateur, in 1988.23 Interestingly, the Automobile et Touring Club du Liban (ATCL) in Kaslik24 also regularly hosted exhibitions, some of which were organized by Galerie Chahine before it opened its branch in the “Solemar” resort.25

The exhibition programme at Galerie La Toile was comparable to that of Galerie Damo, featuring mainly prominent artists who had exhibited extensively prior to 1975 including Paul Guiragossian, Said Akl, Naim Doumit, Mohammad al-Kaissi, Joseph Basbous, and sculptor Zaven. Galerie Chahine on the other hand catered more to the younger generation, including artists such as Greta Naufal, Andre Jazzar, and Maroun Hakim. So did Galerie Les Cimaises, which organized many group exhibitions for young artists such as Aram Jughian, Theo Mansour, and Samir Müller, but also included established artists such as Jean Khalifé with a posthumous exhibition on the nude model and a collective exhibition on portraits and self-portraits by well-known artists from Lebanon.26

While the establishment of galleries in beach resorts can be perceived as a retreat into a more secluded and private domain, away from the urban environment, there were also practical considerations, such as a dearth of suitable exhibition spaces. But more importantly, a significant proportion of the potential audience that had sought refuge from the conflict in Beirut now resided in these areas (and resorts). This included the gallery owners. Moving homes and gallery spaces, often more than once, was a common practice at the time.27 While the beach resorts, due to their private nature, were not suitable for meetings among artists, they arguably facilitated encounters between “pedestrians” within the resort itself and provided easy access to the gallery spaces. Consequently, they served to recreate, to some extent, the former urban environment of Beirut. Antelias, Kaslik, Zouk Mosbeh, and Zalka were, in contrast, suburban residential zones with some commercial activity but almost no pedestrians and a lack of convivial infrastructure, such as cafés where chance encounters might occur.

The shift from Beirut to other areas in Lebanon after 1977 represents a rupture in many ways. While prewar Beirut with its cosmopolitan atmosphere had been an amalgam of a multitude of nationalities, cultural backgrounds, and religious affiliations, Galerie Damo was set up in a different reality, namely that of fragmentation and segregation. It is worth noting Sarah Rogers’ argument that Lebanon’s cosmopolitanism presented itself as a cosmopolitan nationalism, which was “intimately associated with a Maronite Christian community that privileges a Franco-Mediterranean identity over a regional Arab one in Lebanon.”28 Antelias, where Galerie Damo was located, was initially an agglomeration of a few residential houses, in a predominantly Christian area. During the war years it underwent a substantial transformation as a result of the influx of former residents of Beirut and other regions who relocated to this area north of the capital, but remained essentially Christian.

Galerie Damo, the name stands for Décorateurs et artistes du Moyen-Orient, was a design office and an art gallery at the same time. Situated on the first floor of a building opposite the Armenian Church in Antelias, it consisted of three spaces. The gallery was founded by Tripoli-born sculptor and furniture designer Brahim Zod (b. 1942). Together with his wife, the artist Souleima Zod (b. 1944), and Jacqueline Zogheib, wife of the poet and writer Henri Zogheib (b. 1948), he managed the space between 1977 and 1988. The gallery formally existed until 1988, although its last exhibition took place in 1986. In the intervals between exhibitions, the space was frequently utilized as a furniture gallery.

Prior to the gallery opening on 17 November 1977, an exhibition within the “Lebanese Cultural Week in Rome” (8–13 October 1977) prepared the grounds for the inaugural exhibition at Galerie Damo a few weeks later.29 Organized by Father Maroun Atallah (1928–2022) and Les amis de Charbel, the Lebanese cultural week and exhibition in Rome centred on the figure of Saint Charbel, who was canonized by Pope Paul VI on 9 October 1977. Maroun Atallah was a cleric at the Saint Elias Convent in Antelias and the co-founder of the Cultural Movement Antelias, located at the same premises.30 In 1977 he reached out to Brahim Zod, who had started the process of opening his gallery, to assist with organizing the exhibition in Rome. In preparation for the exhibition a board was formed, including Yusuf al-Khal, May Menassa (1939–2019), writer and art critic at the Lebanese daily an-Nahar, Samia Tutunji (1939–89), founder of Galerie Platform, and others.31 The board agreed to include works by well-known artists Jean Khalifé (1923–78), Paul Guiragossian (1926–93), Samir Abi Rached (b. 1947), Rafic Charaf (1932–2003), Hussein Madi (1938–2024), Saliba Douaihy (1915–94), Moustafa Farroukh (1901–57), Omar Onsi (1901–69), César Gemayel (1898–1958), and Gibran Khalil Gibran (1883–1931).

Galerie Damo’s inaugural exhibition, L’exposition des amis de Charbel, ran from 17 to 30 November 1977 and comprised a total of fifty-nine works. On the day of the opening, acclaimed art critic Victor Hakim (1907–81)32 left a short note in the guestbook of the gallery, which read “Exposition collective et homogène” (“Collective and homogenous exhibition”). Another entry, dated 25 November 1977, states, “Damo, espoir de l’unité nationale” (“Damo, hope of national unity”).33 Both entries highlight the collective endeavour that put artists of different backgrounds, styles, and eras in dialogue, and the homogenous and harmonious result as a desirable template for Lebanon. It was seen as a sign of hope for national unity, albeit from a Christian perspective. This was particularly significant given the two years of war and the dissolution of a formerly vibrant artistic scene.

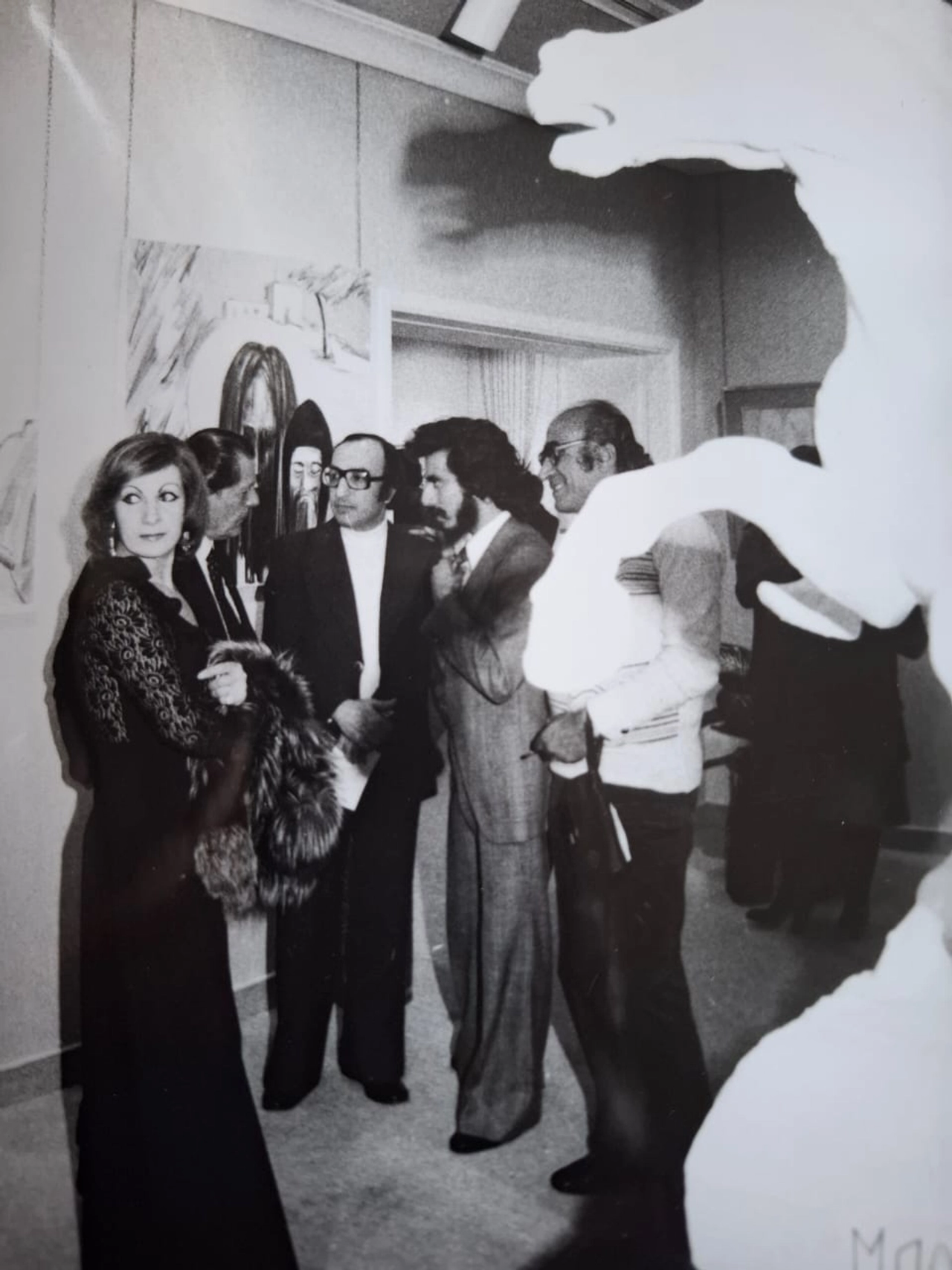

The exhibition in Rome and its subsequent iteration at Galerie Damo shared a nearly identical body of works, with the exception of paintings by Saliba Douaihy and Gibran Khalil Gibran.34 Instead, works by painters Souleima Zod, Maha Bayrakdar (1947–2025), Wajih Nahlé (1932–2017), Joseph Matar (b. 1935), Cici Sursock (1923–2015), and sculptors Halim El Hajj (1915–90) and Antoine Berberi (b. 1944) were added (fig. 1 and fig. 2). Brahim Zod was well connected within the artistic scene in Lebanon, which enabled him to leverage these relationships when he opened his gallery. The exhibition was regarded as an illustrative cross-section of the artistic representations of Lebanon, encompassing its natural environment, cultural heritage, and traditions.

Despite the considerable stylistic diversity among the participating artists, they were unified by a common focus on Lebanon, its landscape across different seasons, the mountains, and Saint Charbel. While the claim was that Saint Charbel addressed all the Lebanese, both Christians and Muslims, he was however deeply rooted in the Maronite homeland of Mount Lebanon and strongly remained a Christian figure with limited capacity to unify. He is the product of the “search for local authenticity (as opposed to Western influence) and the constitution of a ‘national’ community narrative,” as Bernard Heyberger points out.35 Hence, the idea of showing this exhibition in Lebanon could be interpreted as an attempt to start anew with the figure of the “Christian hero,”36 to whom the power to save the nation is attributed by the Maronite leadership to this day.37

The question of whether the establishment of Galerie Damo and the inaugural exhibition represent a project of national unity, which was not an explicit goal of the gallery itself but rather a hope expressed in the guestbook, remains to be addressed. What nation are we talking about, who was included or excluded? While Beirut as a “nexus of transnational Arab artistic encounter,” in Zeina Maasri’s words, and a cosmopolitan space had gradually been disintegrating since the beginning of the war, activities shifted partially to the predominantly Christian regions north of Beirut. Not only did the capital lose its former status as a unifying space for diverse and often divergent ideas, backgrounds, and opinions, but Lebanon itself as a multi-confessional space, with the Christian-Maronite community claiming a leading role, was under scrutiny.

Therefore, the vision of “national unity” may have played a role in holding this exhibition in Lebanon, especially since it was initiated by Les amis de Charbel and the Cultural Movement Antelias, one of whose objectives it is to “strengthen national unity.”38 There may also have been pragmatic reasons for kicking off the gallery programme with an exhibition that was (almost) ready with only the gap left by the withdrawn paintings of Saliba Douaihy and Gibran Khalil Gibran to be filled.

It is difficult to assess which artists, if any, were excluded after the two-year-hiatus between 1975 and 1977. Most foreign artists, including the Arab artists, had left the country, as had many Lebanese. Many of them, however, did not cut their ties with Lebanon and exhibited there when the opportunity arose. Therefore, it is perhaps more appropriate to think in terms of absences rather than exclusions. One observation regarding the confessional background of the public is striking, although not surprising given the location of the gallery in Antelias. The vast majority was from Christian backgrounds. The same applies to the artists, with the exception of Amine El Bacha and Rafic Charaf. It should be pointed out that the gallery itself was in no way biased in terms of sectarian background. However, the situation, especially in the early days of the war, when being affiliated to the “wrong” sect could be dangerous, did not encourage cross-regional exchange, which significantly limited the heterogeneity of both the artists and the public. The public consisted mainly of residents of the surrounding areas and of Beirut with a professional background, often linked to educational, research, and cultural institutions such as the Université Saint Esprit Kaslik, the Institut français d’archéologie, the Collège Notre Dame de Jamhour, the American University of Beirut, the Lebanese University, and the Goethe-Institut, as evidenced by the guestbook entries. Professions also included a number of businessmen, physicians, dentists, professors, and lawyers. There was a great interest in art at the time and “the need to deny the horrors of the war and maintain a semblance of civilized living,” as Brahim and Souleima Zod recall.39 It was “essential to experience the regenerative power of the creative act […].”40 Moreover, “people with money to spend and nowhere to go were in spendthrift mode and eager to buy,” notes Helen Khal.41 As many of them had to redecorate their homes, either because of war damage or relocation, there was also increased demand.

Another observation that deserves some thought is the decrease in the number of female artists exhibiting at Galerie Damo.42 Only five women as opposed to twenty-two male artists exhibited at the gallery (including solo and group exhibitions). This is remarkable in that the number of female artists in Lebanon who had been exhibiting since the 1960s was considerable. Compared to Gallery One and Contact Art Gallery this seems like a drastic discontinuation of past practices from almost half, to one third, to one quarter of female artists.43 However, this absence was probably due to the war and the fact that many artists – both male and female – had left Lebanon or were unable to produce art under the circumstances. It was probably felt more acutely given that the total number of exhibitions was quite limited.

It is also noteworthy that experimental art, often using new media such as installation, video, and performance, and focusing on the effects of the war on the individual and on society, was largely absent in the commercial galleries.44 However, some foreign cultural centres in Beirut, most notably the Goethe-Institut, promoted these art forms in the 1980s.45 What was lacking were institutions that supported experimental art forms and a market for them.46 Since the mid-1960s, the market had been dominated by commercial galleries that “favor painting and sculpture – objects appropriate for domestic decoration.”47

Going back to Galerie Damo and its programme following the inaugural exhibition, the gallery started the year 1978 with an exhibition of works by Rafic Charaf (19–31 January 1978), followed by Maroun Hakim (16 February–2 March), Souleima Zod (27 April–2 May), and Alfons Philipps (25 May–8 June). When hostilities resumed, the exhibition programme was suspended for the rest of the year.48 From then on, exhibitions took place irregularly, accompanied by an increasing discrepancy between the planned and actual outcomes. In 1981, for example, only two exhibitions were held, by Georges Guv (12–21 February) and Elie Kanaan (11–21 December).49 All other scheduled events were cancelled or postponed due to the prevailing circumstances. The gallery’s activities reached a peak in 1980 with a total of seven exhibitions and a low in 1984 and 1985 with no exhibitions at all. The average number of exhibitions was between two and four for the other years. The daily routine of shattered plans and continuous cancellations and postponements was characteristic of this time and applied to all galleries.

In his opening speech on 17 November 1977, the main points of which had been announced at a press conference two days earlier, Brahim Zod underscored the role of art in society and its capacity to heal the wounds of war.50 He outlined the mission and objectives of Galerie Damo, which included the organization of monthly exhibitions featuring artists from Lebanon and abroad, in addition to yearly group exhibitions.51 The latter were to be curated and organized by a designated group of artists and art critics. In terms of media, the gallery’s focus was unambiguous: painting and sculpture. Nevertheless, Brahim Zod’s vision extended beyond the mere exhibition of art. He sought to establish the gallery as a cultural centre, hosting a diverse range of cultural events, including poetry readings, theatrical performances, and musical events.

Galerie Damo was also seeking collaboration with other galleries with the objective of releasing an annual publication of all exhibitions held in Lebanon during the preceding year. The publication was intended to include detailed information about the exhibited works, the prices at which they were sold, and which works were still available at the galleries. Furthermore, the intention was to provide information regarding the artists, including their educational background, artistic trajectory, and stylistic approach.52 This was a novel and challenging approach that required a high degree of transparency and collaboration between galleries. The renewed outbreak of the war in 1978 stopped the pursuit of this ambitious project as communication, mobility, and thus collaboration became even more difficult. The outcome could have served as a valuable documentation of gallery activities and the evolution of the art market in Lebanon, simultaneously serving to unite the various artistic communities in the country.53

A related field Brahim Zod intended to work on and improve was the professionalization of art galleries and their commitment to promote and represent the artists they were collaborating with. This encompassed the regulation of prices and the marketing of artwork. Accordingly, Galerie Damo sought to collaborate with other galleries in Lebanon to establish a “quota” that would regulate prices and respect the artist and their creative output.54 In an interview with the Lebanese weekly al-Hawadith from 1980, Zod asserted that, until then, no institutions in Lebanon or the Arab world had adopted a sound approach in the field of art. What was lacking, he said, were relationships between artists and galleries that extended beyond the often hasty preparations for an exhibition, which did not take into account the artists’ need for ongoing support and a climate in which they could create without having to think about sales.55 Artists were usually not committed to a particular gallery, and vice versa. This resonates with what Waddah Faris from Contact Art Gallery and others had previously envisaged. In an interview with the Lebanese francophone newspaper as-Safa, Faris responded to the question why artists often switched galleries: “Because the galleries are not really organized. They are not yet complete ‘establishments’ with all the concerns that go with them.”56 Following Faris, the relation between artists and galleries needed to be strengthened through the continuous promotion of the artist. The same point was previously articulated by Helen Khal in 1963 as one of the explicit objectives of Gallery One, which was to “bring order to the existing chaos in art exhibition and pricing.”57 Consequently, Zod was not introducing any novel ideas; rather he was picking up the threads of previous efforts and addressing a problem that still needed to be solved.

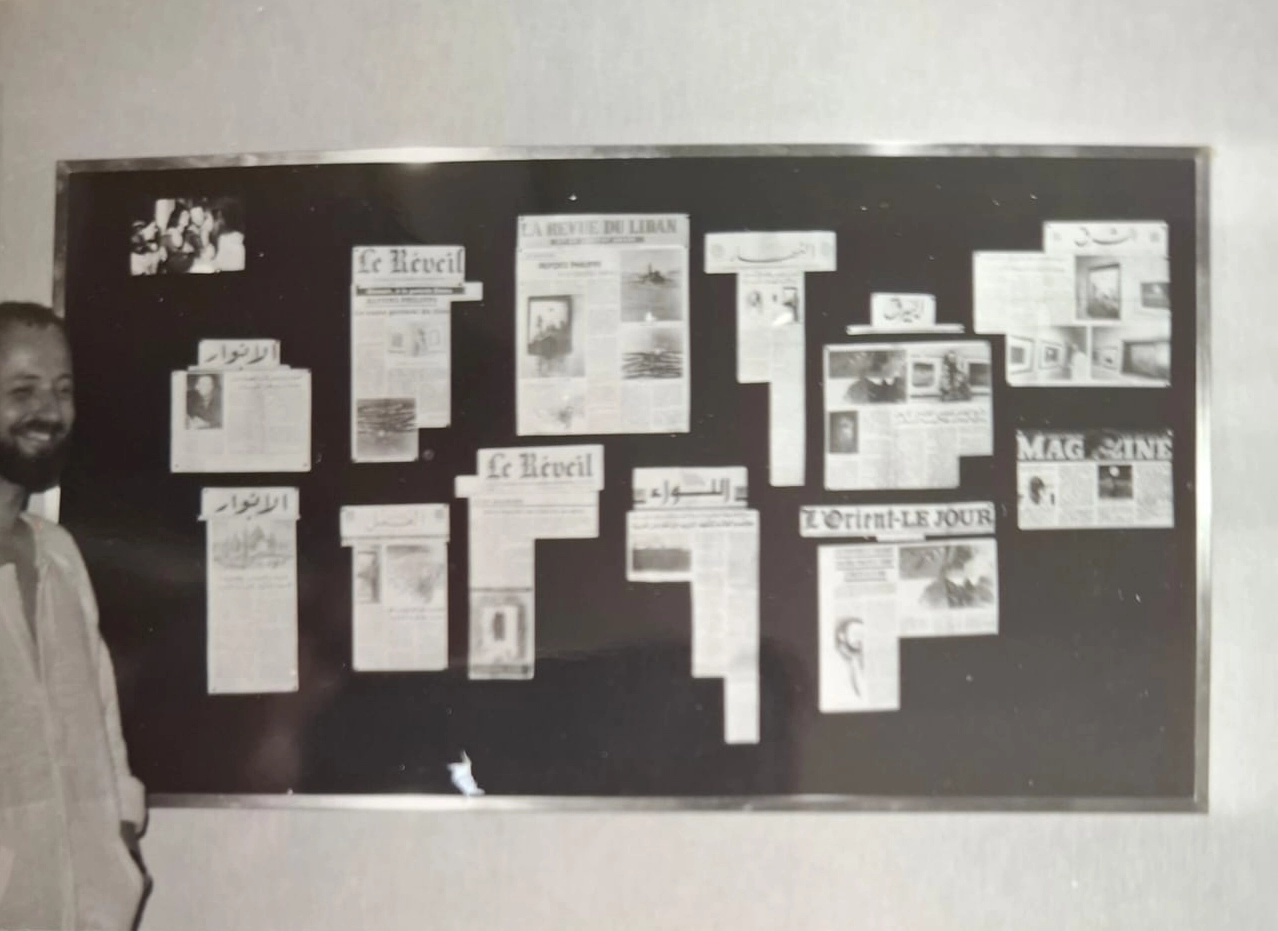

He was also keen on further developing the appreciation for art among the Lebanese through close collaboration with art critics (fig. 3). Zod perceived the role of the gallery to be that of an intermediary between artists and their publics. In advance of each exhibition, he invited art critics to engage in discourse with the artists, thereby gaining an in-depth understanding of the respective exhibitions and the artists’ intentions and artistic approaches. This was because, as he says, there was “nothing more challenging for the artist than to teach his audience how to read his painting or sculpture.”58 This resonates with what Kirsten Scheid has observed about art appreciation and the perceived gap between artists and audiences, particularly in comparison with abroad.59 Brahim Zod’s approach seems to have borne fruit insofar as exhibition reviews became more informative, providing readers with background information on the artists in addition to their work.60 Before, other galleries such as Gallery One and Contact Art Gallery had maintained close relationships with art critics as well. This practice culminated in what was initially planned to become a series of public meetings with art critics as part of the programme at Contact Art Gallery in 1978.61

The gallery also expressed interest in fostering international collaborations and disseminating knowledge about Lebanese art abroad. At the opening, Brahim Zod announced the idea of reciprocal exhibitions:

Galerie Damo is currently contacting foreign galleries to arrange for Lebanese artists to exhibit abroad in exchange for international artists exhibiting here. This helps educate our audience and spread our art to international galleries. It also shows respect for our art because our artists do not always exhibit in the most distinguished galleries abroad.62

The aim was to encourage artists to exhibit as part of an exchange rather than individually to ensure that they would be shown in prestigious galleries. In the end, however, Zod felt it was more important to “build ourselves up inside Lebanon before we go out into the world.”63 This points to the aforementioned relationship between “here” and “there,” and between those who need to be “educated” (the local public) and those who “teach” (the local and foreign artists).

In addition, Galerie Damo sought to cultivate relationships with collectors by sending out individual, targeted invitations prior to the opening.64 Each collector was received individually in order to maintain discretion. On the day of the opening, some works were already sold, as indicated by red dot stickers, which potentially encouraged others to purchase as well.65

Brahim Zod articulated a keen interest in providing support to young and emerging artists. However, Galerie Damo’s primary objective was to showcase established artists and to “preserve Lebanon’s artistic tradition.”66 For this purpose, he sought to collect works of deceased artists and to “market them at a price commensurate with the artist’s value and reputation.”67 Hence, Galerie Damo was more concerned with preserving and distributing knowledge about the artistic canon in Lebanon than trying to pave the way for new generations and experimental approaches in art. Maroun Hakim (b. 1950) was the only young artist who started his career at Galerie Damo.68 It was rather outside the regular gallery programme that Brahim Zod promoted young and emerging artists. In 1980 and 1981, he organized two group exhibitions for young artists in collaboration with the Cultural Movement Antelias which were held at the premises of the Saint Elias church.69

The points that Brahim Zod mentioned in his opening speech were representative of the fundamental aspects of an art gallery. In this regard, they were not novel. However, in the Lebanese context, where a comprehensive gallery system was not yet fully established, as various gallerists had repeatedly claimed, these points were worthy of consideration, particularly in the aftermath of two years of war. In this regard, it was a new and invigorating beginning, underscoring collaboration as a means of restoring connections.

The gallery’s artistic identity and mission were not defined following any specific medium (with the exception of painting and sculpture) or aesthetic lines, but put “quality” centre stage. As Zod explains,

[T]he primary objective in organizing these exhibitions is to provide the public with novel experiences, but above all to maintain a certain quality, which necessitates a meticulous selection of painters according to highly specific criteria. There is a considerable number of artists who express a desire to exhibit their work. However, it is not the intention of this establishment to encourage mediocrity by commercializing art. Nevertheless, Galerie Damo is open to the general public, as it aims to serve as a hub for the primary trends in visual arts in Lebanon.70

This placed Damo Gallery in alignment with numerous other galleries, including Gallery One, La Toile, Alwane, and Épreuve d’artiste, which univocally employed a singular criterion for acceptance: the quality of the work, irrespective of the artist’s style or training.71 In an undated typescript by Helen Khal, probably from the mid-1960s, the author discusses the role of the gallery, which

akin to that of the critic, must be to establish for the public reasonably reliable standards of quality. It must weed out the unready or bad artist, and try to show and sell only what it believes to be good art. Only on this basis can it build a reputation of reliability and honesty. […] And a clientele that trusts their judgement is what they keep looking for.72

The emphasis placed by gallerists on the importance of “quality” (as a criterion for exhibiting artwork in an art gallery) is a self-evident aspect of the gallery’s role. However, it may have been a way of distinguishing themselves from other venues such as hotels, where any artist could rent a space and exhibit without anyone “to tell him whether his work [was] worth showing or not,”73 by underscoring the fact that it was the gallery that selected the artists, rather than the artists who presented themselves.

In addition to its exhibition programme, Galerie Damo functioned as a cultural space.74 The gallery regularly organized book signings, poetry readings, gatherings, musical and theatrical representations such as the staged reading of the play al-Mekenseh (“The Broom”) by the author, poet and playwright Thérèse Basbous (1934–2020), wife of the sculptor Michel Basbous, on 4 February 1985.75 Nohad Salameh’s poetry book signing of “Folie couleur de mer” in December 1982 in conjunction with the exhibition opening of Françoise Muller, which attracted “a large crowd comprising the political, diplomatic, cultural and artistic elite of Beirut, as well as members of the business community and the press […],”76 is another example of Galerie Damo’s cultural activities.77

The gallery was close to the theatre scene and frequented by numerous theatre directors, playwrights, and actors such as Raymond Gebara, Jalal Khoury, Shakib Khoury, Rifaat Torbey, and Antoine Kerbaj, and musical composers such as Elias Rahbani. The idea of organizing a meeting at the gallery in October 1980 for Ellen Stewart (1919–2011), founder and director of the La MaMa Experimental Theatre Club in New York City, was therefore evident (fig. 4).78 Poets, writers, and art critics were also regular visitors and friends of the gallery. Among them were Unsi al-Hajj, Yusuf al-Khal, Joseph Tarrab, Nazih Khater, César Nammour, and many others (fig. 5). Weekly gatherings were held at the gallery, attended by members of these circles. Galerie Damo appeared to fulfil a need for exchange, and its vision to act as a cultural centre worked out in that sense. The meetings also provided a forum for exchange on matters pertaining to art and cultural politics. When the gallery closed in 1988, these gatherings continued in hotel venues. Together with the weekly meetings at Yusuf al-Khal’s house in Ghazir, in which Brahim Zod and others participated, they can be seen as a continuation of prewar practices, where meetings had become institutionalized, first with Yusuf al-Khal’s poetry magazine Shi’r and its “Thursday gatherings” and later on meetings at Gallery One and Contact Art Gallery. It was also an effort to bring together different artistic disciplines and to encourage exchange among artists.

Comebacks and New Beginnings

A number of artists made a comeback at the beginning of the 1980s. Some returned or visited from abroad, while others resumed their work and exhibited after several years of silence due to the war. In March 1981, for instance, newspapers enthusiastically announced the comeback of the artist Krikor Norikian (b. 1941), who had been living in Paris since 1974, with an exhibition entitled Rêves capturés, to be held at the Planula Elissar Visual Arts Center from 2 to 18 April 1981.79 Another artist who made a comeback in 1981 after several years of silence was the sculptor Nazem Irani (b. 1930), who exhibited several works at the UNESCO Spring Exhibition. However, he deviated from his usual media and exhibited paintings instead of sculptures: “I would like to forget about sculpture for a while.”80

Galerie Damo also offered a platform for comebacks and new beginnings: when Pierre Sadek (1938–2013) exhibited at Galerie Damo from 12 to 22 March 1980, it was his first exhibition after twenty years (fig. 6).81 He was well-known as a political caricaturist, having previously worked for the Lebanese daily an-Nahar and working for the newspaper al-ʿAmal at the time of the exhibition. Sadek surprised his audience with thirty-six drawings revealing a “visual technique” (“une technique plastique”).82 His black and colour ink drawings rendered in a “surrealistic and expressive” style, as Sadek himself describes them, put the focus on the human condition and the nature of existence.83 In contrast to his political cartoons, which consistently referenced current political developments, these works diverged in their focus. Reflecting on the atrocities of the war, Sadek’s intention with this exhibition was to work against oblivion: “‘My objective was to convey the Lebanese people’s silence, their aspirations, and their daily lives.’ […] These are neither caricatures nor paintings. These are canvases created by Pierre Sadek.”84

Pierre Sadek’s exhibition was the first of its kind in his long career as an acclaimed political cartoonist. The audience, including some art critics who were used to his political caricatures reflecting on the political, economic, and social themes of war-torn Lebanon, found it challenging to categorize his works, which were situated between caricatures and paintings.85 Unlike his political cartoons often tied to a precise event, his new paintings had a more universal character, which made them suitable to be “displayed permanently, in a living room, without fear of being outdated the next day or even a year from now.”86 With the works in this exhibition reflecting on the human condition, the artist sought enduring images in times of rapid change. The experience of war, which led to his comeback in an art gallery, urged him to seek more depth in his artistic expression.

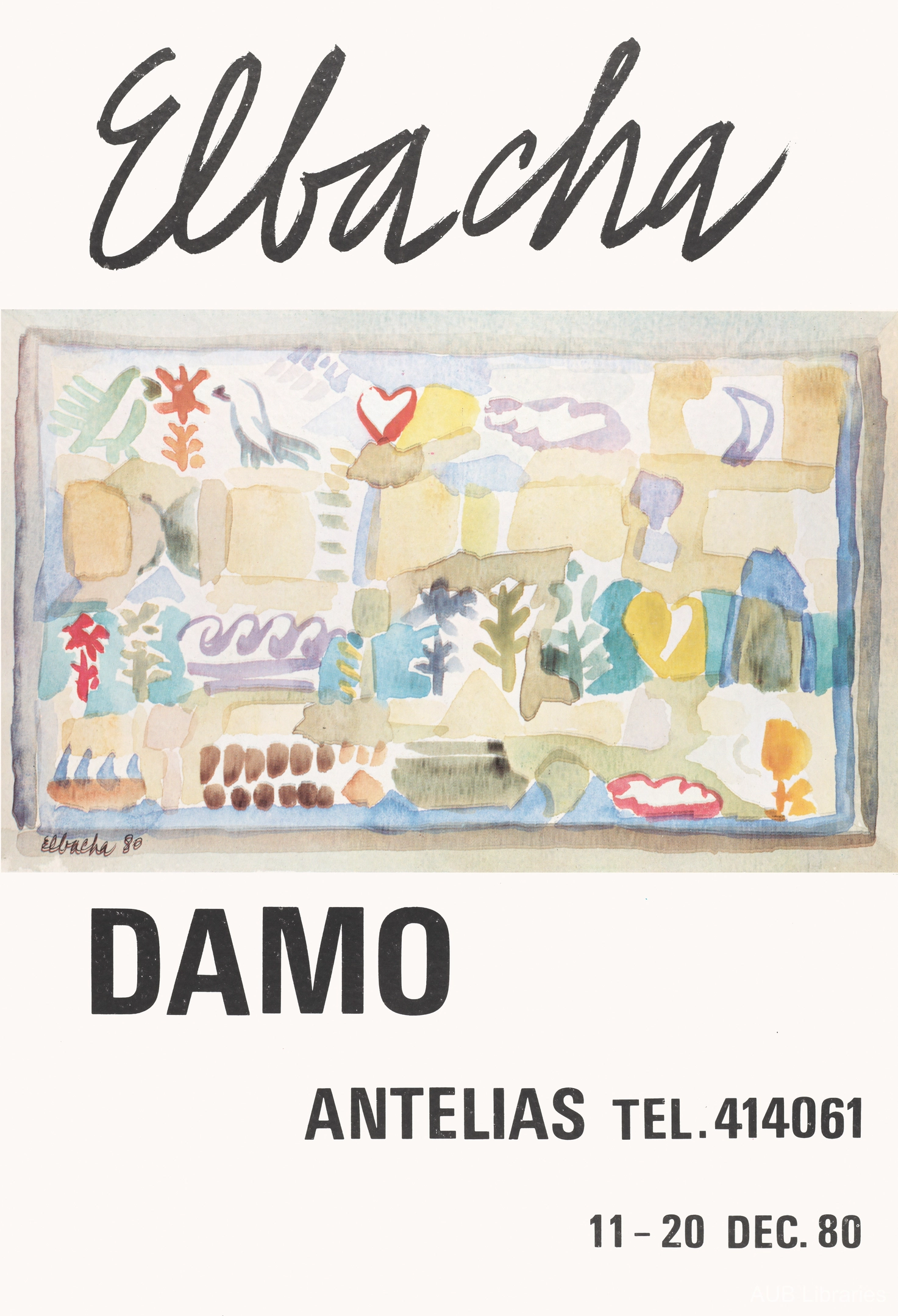

Another artist who was having his comeback was Amine El Bacha (1932–2019). Following a period of several years in Italy, the artist’s first exhibition back in Lebanon took place at Galerie Damo between 11 and 20 December 1980 (fig. 7). El Bacha employed formats that were markedly disparate from one another, a departure from his customary practice. The exhibition comprised fifty-eight miniature watercolour paintings, one ink drawing, and one large-scale work covering two entire walls at the gallery.87 Despite the unconventional format, the works themselves remained consistent with the artist’s established style, which typically depicted interiors, flowered terraces, gardens, marine landscapes, and flower arrangements. Art critic Nazih Khater, who covered the event, highlighted the artist’s consistent artistic qualities while also noting a lack of experimentation and innovation in his work:

It appears that the exhibition at Galerie Damo was assembled without a discernible plan or conscious effort. The work does not intend to transmit any particular vision or to explore the specific characteristics of watercolour as a medium with the intention of changing its meaning, role, or dimensions. The works appear to be a reiteration of previous pieces by the same artist.88

In the view of Nazih Khater, the exhibition at Galerie Damo demonstrated “some kind of visual memories” rather than the artist’s present artistic preoccupations. It was as though Amine El Bacha was “offering us professional remains, leaving his living experiences for the future.”89 Some art critics had anticipated a novel development in the artist’s approach, particularly given his prolonged absence from Lebanon.90 His “comeback” was thus a return to his established style rather than a reinvention under new circumstances.

While Pierre Sadek’s engagement with Lebanon, politics, and the war is evident in his work, Amine El Bacha’s is more nuanced and obscured beneath the colourful, seemingly carefree surface. In an interview with Etel Adnan in 1972, Amine El Bacha gave a potential explanation for this absence: “However sad the artist may be, the gesture of art is always positive, always a belief in happiness. That is why I think there are very few works that are sad, even if their subjects are sad.”91 In his work, El Bacha offers a compensatory vision that counters the disillusionment of the prevailing reality with a vision of hope and imagination. In an interview with journalist Mirèse Akar on the occasion of El Bacha’s exhibition at Galerie Faris in Paris in 1982, the artist elaborated more on the relation of war and artistic creation, offering his personal perspective:

In Lebanon, even though my attitude tended to put the war between parenthesis, the situation encouraged me to make some works based on chronology: for example, to represent a tree from its germination to its death, which amounted to representing the passage of time, which the war may have made us measure differently.92

The invitation card that accompanied the exhibition at Galerie Damo also echoed the artist’s playful gesture and served to further illustrate his deep and enduring connection to Lebanon. It shows El Bacha’s ability to combine images and text in a manner that is both poetic and humorous. The motifs are all related to Lebanon, its nature, traditions, and mythology, with birds, hearts, flowers, fish, horses, men, and women floating through this dream landscape. In the midst of these elements, the viewer encounters poetic sentences such as, “I saw a white dove blending in with the white clouds… nothing could be more normal… The white clouds soften the blue sky… The sky of Lebanon” (fig. 8).93

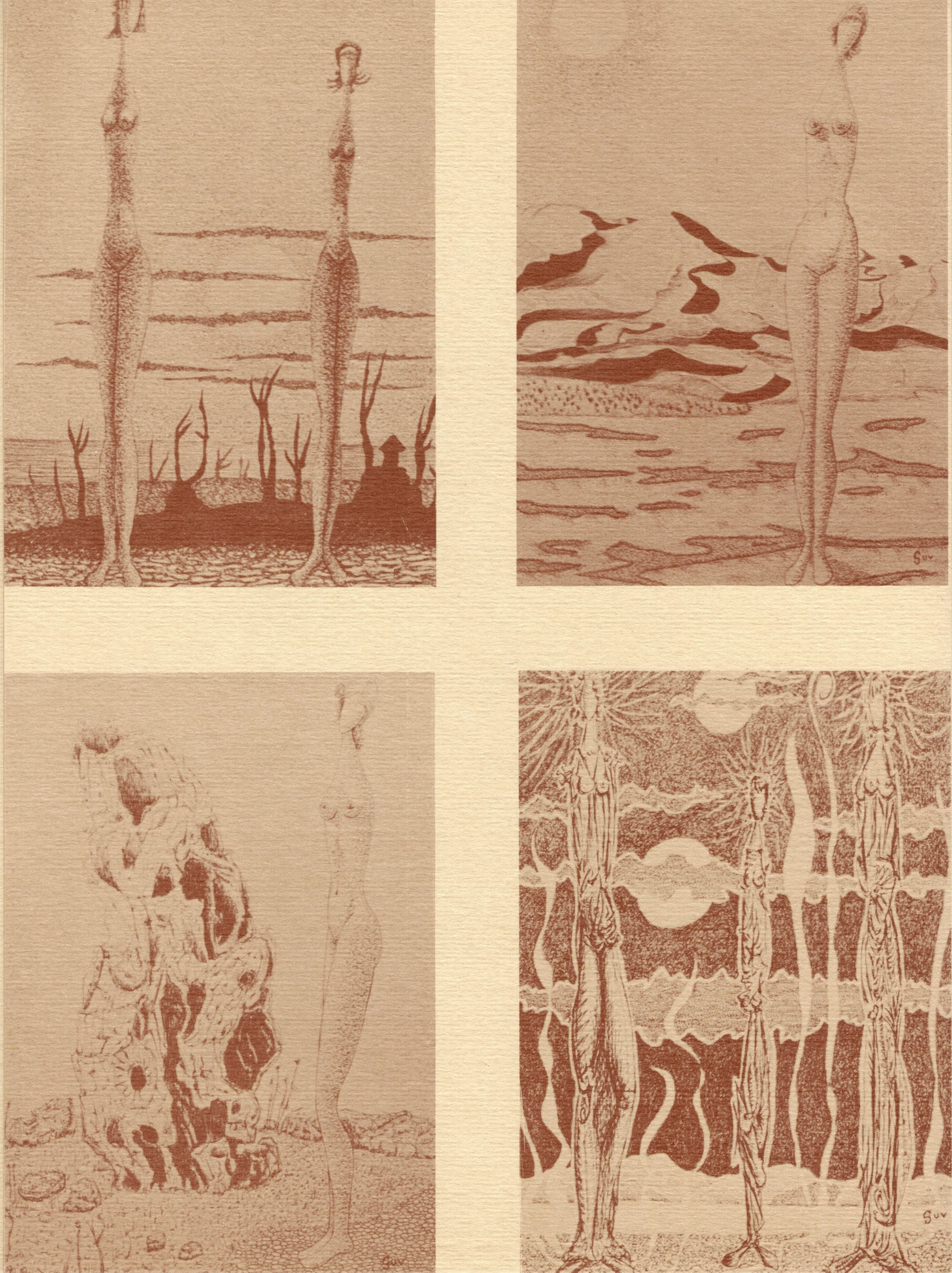

The series of comebacks continued when Guv (1918–90) held his exhibition at Galerie Damo from 12 to 21 February 1981. It was his first after six years of silence following the outbreak of the war.94 The exhibition comprised fifty-one works created using a pointillistic technique, primarily featuring the female figure set against dreamlike, often submarine landscapes with the sun/moon being a recurrent element in these compositions. The vertical woman is depicted without arms, imparting a sense of levitation reminiscent of seaweed in the artist’s landscapes (fig. 9). Fascinated by submarine landscapes in particular, Guv’s drawings have an ecstatic and transcendental power in which “matter annihilates itself and becomes only spirit. It’s the beginning of eternity, an approach to God.”95

The search for the essence of life is what is also intrinsic to El Bacha’s work. However, Guv’s art is deeply rooted in and affected by the misery and suffering of humankind. This includes the pain caused by the Armenian genocide, the war in Lebanon and the catastrophe of Hiroshima: “In my forms, in my beings, there is pain; they are tortured, torn, shredded, pierced, perforated, quartered, but grave and silent, their heads held high.”96 In the context of the war in Lebanon, the artist’s works elucidated the “frightening silence in the face of disaster.”97 The exhibition was well received, as evidenced by the many enthusiastic entries in the gallery’s guestbook, mostly expressed by the word “Excellent!,” but sometimes more detailed: “Guv’s woman fearlessly and thoughtfully contemplates her place in the cosmic scheme. […] Hardly ever works of art are so profound. Fantastic.”98

The three exhibitions briefly discussed here have in common that the artists involved had all been absent from the artistic scene in Lebanon for some time (whether due to physical absence or artistic inactivity because of the war) before taking up this opportunity by Galerie Damo. While both Guv and Sadek offered new insights into their artistic work, Amine El Bacha’s exhibition provided a more comprehensive overview of his artistic output over the past few years. Together with other spaces, Galerie Damo provided a platform for these artists and encouraged their return to the art scene. As a result, the gallery played a pivotal role in sustaining artistic production while offering continuity as well as opportunities for new beginnings despite the difficult situation, which Helen Khal acknowledged as follows:

It was one of the very few galleries that managed to survive and serve art faithfully amid the disruptive, enervating and often dangerous conditions of the ongoing conflict. Other galleries would come and go, but Damo persisted for more than a decade, from 1977 to 1988. At times without electricity, but with a good stock of kerosene lamps on hand for those black-out nights. And with the postal service completely disfunctional [sic], the gallery owners had to depend on a combination of word-of-mouth, telephone messages and hand-delivered invitations to announce its shows and other cultural activities.99

Aquarelle Landscape Painting: A Symptom of the War?

The impact of the war on artistic creation thus varied significantly between individual artists. One noteworthy phenomenon was the increased interest in and production of aquarelle landscape painting during the early 1980s.100 The success of watercolours depicting Lebanese landscapes, village life, and traditions could be interpreted as a longing for “normality,” “purity,” and perhaps “a state of innocence” projected onto the past. Joseph Tarrab critically speaks of aquarelle landscape painting as a phenomenon of the war time period; under the “pretext of preserving the cultural heritage” it steadily increased since the beginning of the war.101 This phenomenon became particularly evident during the 1980s, coinciding with a deterioration in the situation. Concurrently, the pioneers of Lebanese landscape painting, including Omar Onsi (1901–69), Moustafa Farroukh (1901–57), and César Gemayel (1898–1958), witnessed a surge in interest in the art market.102 Landscape paintings were treated as “lenses to a prewar, nationally self-evident Lebanon.”103 The usual absence of people, such as in Omar Onsi’s “typical paysage lubnani,” coincided with the war and postwar viewers’ longing for an “apolitical, unideological, and irreligious” space,104 for a kind of dream: “The pine trees, house, and no people, no cars, no smoke […] sort of a Lebanese form of paradise.”105 The interpretation of images and how they affect us is thus largely shaped by our individual historical and cultural perspective, our aesthetic repertoire, our expectations and needs.

In the early 1980s, many young artists began to produce watercolour landscapes that were highly sought after.106 According to Tarrab, the interest in landscape painting had less to do with its aesthetic qualities (which he often found lacking) than with what it promised in terms of order, tranquillity, and, above all, security and identity.107

Galerie Damo did not follow this trend. Only two individual exhibitions focused on watercolour landscapes, namely Maroun Tomb’s and Amine El Bacha’s exhibitions, as well as some works in the inaugural exhibition. It would appear that a significant proportion of exhibitions featuring watercolour landscapes by artists of the younger generation were held in venues other than the established galleries. Such venues included hotels and other alternative spaces such as the Casino du Liban. The majority of commercial galleries, including Galerie Damo, tended to rely on established artists to represent this genre.

The Lebanese-Palestinian artist Maroun Tomb (1911–81), who fled with his family from Haifa to Lebanon in 1948, and who is known for his watercolours inspired by Palestinian and Lebanese landscapes and village scenes, was programmed twice at Galerie Damo (May 1980 and April 1981) (fig. 10). His paintings, created in a realistic and romantic style, are markedly different from those of Amine El Bacha. In the press, aquarelle landscape painting is often mentioned in conjunction with the war situation in Lebanon, with the aspect of “fraîcheur” (freshness) repeatedly highlighted.108 The freshness and softness of the colours, evoking feelings of well-being, vitality, and enthusiasm created a peaceful atmosphere and offered distraction in these difficult moments. One example of the numerous press articles that were published on the occasion of Maroun Tomb’s exhibition in 1980 emphasizes the therapeutic aspects of landscape painting during the war:

The twilight of Roumieh against the backdrop of the sea, the Abou Ali river, the citadel of Jbeil, the old souk of Tripoli… all enchanting settings that restore Lebanon’s original character and help viewers forget the horrors of war.109

The depiction of nature and mountain villages in their purest form, with the use of earthy tones and soft contours, provided a sense of tranquillity amidst the turbulence and uncertainty of war, responding to the necessity for evasion from the harsh reality by creating a “diluted reality.” Beneath the seemingly picturesque surface, however, lay the unspoken horrors of war, as we can sense from statements that link the use of certain colours to the situation. One example is Sami Abou Kheir’s exhibition at the Casino du Liban in 1980, which included landscapes, trees, and portraits, all coloured pink. In a press article entitled “100 canvases using pink for hope,” the artist said: “It’s not just about hope, it’s also about a return to innocence […] I have expressed a wish, a desire to see my country return to its good days.”110

Unlike the modernist, often abstract paintings of the 1960s and ’70s in Lebanon, which only had a limited and initiated, albeit increasing circle of admirers, landscape painting represented something that one could easily grasp and identify with. The confessional fragmentation of Lebanon as a result of the war was reflected in its regional fragmentation, which was expressed through landscape painting and became an important marker of identity. Although not primarily political, the decision to depict one’s own region or village, though imbued with the desire to seek refuge in nature and local traditions, became an expression of regional belonging. Consequently, it could be considered a form of political expression in itself.

Amidst the changes and ruptures that had taken place in Lebanon since the outbreak of the civil war, Galerie Damo played the role of an anchor of stability and continuity. With destruction all around and the “degradation of artistic standards,” as Joseph Tarrab described it, the gallery focused on established rather than on emerging artists, and on traditional media such as painting and sculpture rather than on experimental art. As a result, Galerie Damo did not explicitly attempt to promote a specific aesthetic or cultural vision with the intention of radically changing or expanding the perception of art. This may also be attributed to the fact that the war had devastated a considerable part of the previously flourishing artistic community, of which Brahim Zod himself was a member, making this relatively “conservative” approach a logical consequence. Galerie Damo was a space for exchange, offering a wide range of cultural activities where artists of all kinds and writers could meet, discuss, and maintain their friendships. It thus served as a bridge between the past and the future, providing opportunities for artists and their audiences to stay in touch, while at the same time working on a structural level to improve the gallery and the art system in Lebanon. As such, it was able to provide much-needed continuity throughout the 1980s, while also offering opportunities for new beginnings. Despite some similarities with prewar galleries such as Gallery One and Contact Art Gallery in terms of the repertoire of artists and the intention of establishing a space for exchange beyond that of a mere exhibition space, Galerie Damo operated in a very different cultural, social, and political context that lacked the prewar prosperity on both the economic and creative levels, as well as its cosmopolitan fabric and its Arab identity. Its founding history in Antelias, outside the cultural centre Beirut, and its inaugural exhibition, initiated by Les amis de Charbel and closely linked to the church, testify to this new framework. However, the gallery was open and in no way tied to regional and other identities, but the war situation limited access to the venue. While Lebanon’s acclaimed cosmopolitanism in the 1960s and ’70s appears to have been rather a cosmopolitan nationalism associated with the Maronite Christian community, as Sarah Rogers has pointed out, one might question whether cosmopolitanism remained a distinguishing feature in the 1980s, or if sectarian nationalism had completely overtaken it.

This research was conducted in the context of the research project Lebanon’s Art World at Home and Abroad (LAWHA), which has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 850760).

Exhibited artists | Year | Duration | |

|---|---|---|---|

1 | INAUGURAL GROUP EXHIBITION with César Gemayel, Omar Onsi, Moustafa Farroukh, Rafic Charaf, Wajih Nahlé, Paul Guiragossian, Jean Khalifé, Joseph Matar, Samir Abi Rached, Cici Sursock, Souleima Zod, Maha Bayrakdar, Antoine Berberi, Halim El Hajj | 1977 | 17–30 November |

2 | RAFIC CHARAF | 1978 | 19–31 January |

3 | MAROUN HAKIM | 1978 | 16 February– |

4 | SOULEIMA ZOD | 1978 | 27 April–10 May |

5 | ALFONS PHILIPPS | 1978 | 15 May–8 June |

6 | ALFRED BASBOUS | 1979 | 8–18 May |

7 | MAROUN HAKIM | 1979 | 29 May–7 June |

8 | ALFRED BASBOUS | 1979 | 14–24 November |

9 | AMINE SFEIR | 1979 | 12–22 December |

10 | SOULEIMA ZOD | 1980 | 16–26 January |

11 | WAJIH NAHLÉ | 1980 | 13–23 February |

12 | PIERRE SADEK | 1980 | 12–22 March |

13 | MAROUN HAKIM | 1980 | 16–26 April |

14 | MAROUN TOMB | 1980 | 14–24 May |

15 | GROUP EXHIBITION ÉTÉ 80 with Amine El Bacha, Alfred Basbous, Maroun Hakim, Wajih Nahlé, Pierre Sadek, Amine Sfeir, Maroun Tomb, Souleima Zod, Liliane Abou Chaar | 1980 | 25 June– |

16 | AMINE EL BACHA | 1980 | 11–20 December |

17 | GUV | 1981 | 12–21 February |

18 | MAROUN TOMB (The opening of the exhibition was cancelled due to the sudden passing of the artist.) | 1981 | 16–25 April |

19 | ELIE KANAAN | 1981 | 11–21 December |

20 | HALIM JURDAK | 1982 | 17–27 February |

21 | FRANÇOISE MULLER | 1982 | 7–17 December |

22 | PAUL WAKIM | 1983 | 31 March–7 April |

23 | SOULEIMA ZOD | 1983 | 20–30 April |

24 | GROUP EXHIBITION AT SALON ALTAVISTA, KASLIK with Amine El Bacha, Michel Basbous, Halim Jurdak, Jean Khalifé, Pierre Sadek, Souleima Zod | 1986 | 3–18 May |

25 | HALIM JURDAK | 1986 | 7–21 May |

26 | MICHEL BASBOUS | 1986 | 11–25 November |

27 | AMINE EL BACHA | 1986 | 9–20 December |

Adnan, Etel. “Amine El-Bacha: Un peintre qui voit passer les avions. Bientôt à la galerie Contact.” As-Safa, 25 October 1972.

Akar, Mirèse. “Amine El-Bacha: Peindre, c’est mettre la guerre entre parenthèses.” L’Orient-Le Jour, 22 October 1982.

Akar, Mirèse. “Shafic Abboud: ‘Plus le monde va mal, plus ma peinture devient joyeuse’.” L’Orient-Le Jour, 7 June 1981.

Arbid, Marie-Thérèse. “‘L’exposition des expositions’, une grande première en son genre.” L’Orient-Le Jour, 19 June 1981.

“Biyar Sadiq yajri mubadala tarikhiyya bayna Adam wa-Hawwa’.” Al-Hawadith, no. 1221, 28 March 1980.

Boullata, Kamal. “Artists Re-member Palestine in Beirut.” Journal of Palestine Studies 32, no. 4 (Summer 2003): 22–38.

Boullata, Kamal. Palestinian Art: From 1850 to the Present. London; San Francisco; Beirut: Saqi, 2009.

“Cardinal Rai Entrusts Lebanon to Saint Charbel.” Vatican News, 20 July 2021. https://www.vaticannews.va/en/church/news/2021-07/cardinal-rai-entrusts-lebanon-to-saint-charbel.html.

Creswell, Robyn. City of Beginnings: Poetic Modernism in Beirut. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2019.

Dahdah, Tina. “Maroun Tomb à la Galerie DAMO. Un bain de fraîcheur… .” Le Réveil, 9 May 1980.

“Des thèmes plutôt que des couleurs.” L’Orient-Le Jour, 16 March 1981.

Fadel, Jihad. “Al-fannan al-lubnani… mazlum!.” Al-Hawadith, no. 1251, 24 October 1980.

Fani, Michel, L’art au Liban. Grenoble: Éditions de l’escalier, 2007.

Fares, Mireille. “Amine el-Bacha: Grande expo le 11 décembre.” Le Réveil, 5 November 1980.

Farra, Sabine. “Ces dames des galeries d’art.” La Revue du Liban, 1986 (exact date unknown).

G., Y. “A ‘Rimal’, les aquarelles-fraîcheur de Mohamed el-Kaissi.” L’Orient-Le Jour, 28 May 1984.

“Georges Zeeni transforme ‘Planula’ en centre vivant de l’art.” L’Orient-Le Jour, 25 January 1984.

Grahne, Taymour. “Amal Traboulsi Interview.” Art of the Mid East. 8 September 2011. https://artofthemideastdotcom.wordpress.com/2011/09/08/amal-traboulsi-interview/.

“Guv et le monde de la femme.” L’Orient-Le Jour, 12 February 1981.

Heyberger, Bernard. “Saint Charbel Makhlouf, or the Consecration of Maronite Identity.” In Middle Eastern and European Christianity, 16th–20th Century: The Collected Works of Bernard Heyberger, edited by Aurélien Girard et al., 245–63. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2023.

Holy Spirit University of Kaslik. “Nohad Youssef Salameh.” Archival Collections. Last accessed 8 July 2025. https://www.usek.edu.lb/phoenix/archival-collections/nohad-youssef-salameh.

“ʾImraʾa musharʾiba tusaytiru ‘ala al-zaman wa al-makan.” Al-Usbuʿ al-ʿarabi, no. 1114, 16 February 1981.

Khal, Helen. “Souleima Zod Transforms the Body into Landscapes of Virtual Reality.” In Resonances: 82 Lebanese Artists Reviewed by Helen Khal, edited by César Nammour et al., 326–29. Beirut: Fine Arts Publishing, 2011. First published in The Daily Star, 19 November 1997.

Khater, Nazih. “Amin al-Basha darbat risha. Dauww talwini li-jughrafiyya wa-zaman.” An-Nahār, 18 December 1980.

Khoury, Hala. “Exposition des œuvres de jeunes peintres.” L’Orient-Le Jour, 4 February 1981.

Khoury, Hala. “‘Il faut sortir du ghetto intellectuel’.” L’Orient-Le Jour, 1 April 1982.

Khoury, Hala. “Noff al-Hadi au Summerland: ‘La mélancolie mène au bonheur…’ … et Abou Kheir au ‘Casino du Liban’: 100 toiles avec le rose pour l’espoir.” L’Orient-Le Jour, 6 June 1980.

“L’Uncle Sam’ fébrile.” L’Orient-Le Jour, 24 June 1981.

“Le comeback de Norikian.” L’Orient-Le Jour, 11 March 1981.

“Le Mouvement culturel d’Antélias présente les artistes non professionnels.” L’Orient-Le Jour, 7 February 1980.

Maasri, Zeina. Cosmopolitan Radicalism: The Visual Politics of Beirut’s Global Sixties. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020.

Malhamé-Harfouche, Nicole. “Une double manifestation à la Galerie Damo. Signature de ‘Folie couleur de mer’ de Nohad Salameh, vernissage des œuvres récentes de Françoise Muller.” La Revue du Liban, 11 December 1982.

MCALEB. “Les Objectifs du movement Culturel – Antélias.” 5 December 2007, https://www.mcaleb.org/fr/introduction/objectifs.html.

Momdjian, Bernadette. “Explorateur de ce champ clos qu’est le monde.” Le Réveil, 13 October 1981.

“On travaille au ralenti en attendant la reprise.” L’Orient-Le Jour, 2 November 1983.

“Opening of Gallery One: A First Art Institution of Its Kind.” MoMa Primary Documents, edited by Anneka Lenssen et al., 206–8. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2018.

“Pierre Sadek et la caricature sociale.” Magazine, March 1980 (exact date unknown).

Rogers, Sarah. “Postwar Art and Historical Roots of Beirut’s Cosmopolitanism.” PhD diss., Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Department of Architecture, 2008. http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/45935.

Safar, Claude. “Waddah Faris et l’avant-gardisme dans les pays arabes.” As-Safa, 17 August 1972.

Salameh, Nohad. “La caricature ou l’amertume du rire.” Le Réveil, 13 March 1980.

Scheid, Kirsten L. Fantasmic Objects: Art and Sociality from Lebanon, 1920–1950. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2022.

Tarrab, Joseph. “Liban, société de guerre et créativité, arts plastiques et théâtre: de la galaxie au trou noir.” In Les conférences de l’ALDEC, Liban: Société en guerre et créativité, 19–40. Beirut: Université Saint-Joseph, 1987.

Tarrab, Joseph. “Quoi? L’éternité. Amine El Bacha à la Galerie DAMO.” L’Orient-Le Jour, 16 December 1980.

Thomas, Fabienne. “Bilan et perspectives des galeries ‘Damo’ et ‘Épreuve d’artiste’. Continuer à l’intention d’un public assoiffé d’art… .” L’Orient-Le Jour, 14 January 1982.

Traboulsi, Amal. Galerie Épreuve d’artiste: Chronologie d’une galerie sur fond de guerre. Beirut: Épreuve d’artiste, 2018.

Zalzal, Zéna. “Odile Mazloum: J’ai dans ma tête et dans mon cœur des centaines de toiles… .” L’Orient-Le Jour, 20 July 2020. https://www.lorientlejour.com/article/1226454/odile-mazloum-jai-dans-ma-tete-et-dans-mon-coeur-des-centaines-de-toiles.html.

Zod, Brahim. “Bayan iftitah Galiri Damu – Antelias, yawm al-khamis, 17 tishrin al-thani 1977.” Unpublished Arabic typescript, dated 14 November 1977 and held at the archive of Galerie Damo.

Zogheib, Henri. “Damu Bayrut… li-Lubnan wa al-sharq al-awsat.” An-Nahar, 14 November 2023. https://www.annaharar.com/culture/news/190871/دامو-بيروت-للبنان-والشرق-الأوسط.

Zogheib, Henri. “Takrimuhum fi al-watan wa fannuhum fi... al-ʿalam.” Al-Hawadith, 25 November 1977.