In 1982, Jamil Molaeb exhibited woodcut prints in West Beirut, capturing life during the Lebanese Civil War. His series Akhir al-zalam, awwal al-fajr (The End of Darkness, the Beginning of Dawn) stood out for its portrayal of wartime experiences. Molaeb’s work drew on regional artistic influences, particularly those of Palestinian artist Mustafa al-Hallaj, highlighting the interconnectedness of artists in the region affected by conflict. This exhibition stood out for its exploration of war themes through the medium of woodcut prints, a choice reflecting both artistic intent and the material realities of wartime Lebanon.

This paper examines the relationship between the visuality of black-and-white prints and the representation of war motifs in Lebanese art during the civil war. The prevalence of war-themed prints and posters shaped the visual culture of Lebanon, yet the genre faced limited commercial appeal, pushing artists and galleries back toward mainstream art. By analysing these dynamics, this paper reconsiders how Lebanese artists documented and engaged with the civil war through underrepresented artistic media.

Printmaking, Lebanese Civil War, 1975–1990, Graphic Arts, Visual Culture

This article was received on 14 October 2024, double-blind peer-reviewed, and published on 17 December 2025 as part of Manazir Journal vol. 7 (2025): “Defying the Violence: Lebanon’s Visual Arts in the 1980s” edited by Nadia von Maltzahn.

Art historical accounts often describe the civil war period in Lebanon (1975–1990) as an artistic standstill compared to the alleged Golden Age preceding it.1 These accounts characterize artistic production of this period as being disconnected from regional aesthetic discourses and disengaged from the socio-political realities of the conflict. Contrary to this narrative, however, a notable amount of art was produced and shown throughout the war, evident in numerous exhibitions in a variety of media and themes.2 Within the war-torn landscape, printmaking emerged as a powerful tool of expression, documenting the realities of conflict while engaging with a broader regional aesthetic discourse.

Representing one of the most compelling examples of this phenomenon were the woodcut prints by Jamil Molaeb (b. 1948). On 4 February 1982, within the walls of the Galerie Épreuve d’Artiste in West Beirut, viewers were drawn to a collection of black-and-white woodcut prints that gave an impression of the human experience during the war.3 These evocative works from the series Akhir al-zalam, awwal al-fajr (The End of Darkness, the Beginning of Dawn) constituted the third in a trilogy of albums created since the outbreak of the civil war.4 While Molaeb’s exhibition received wide attention, the same did not apply to all artists engaging with war motifs. Beirut-based Palestinian artist Mustafa al-Hallaj (1938–2002), despite his pioneering contributions to Arab contemporary graphic arts, was relatively absent in Lebanon’s mainstream artistic discourse of the time. Art critic Hassan Badaoui, for instance, considered Molaeb as integral to what he called “the Lebanese artistic movement,” whereas he did not consider al-Hallaj to be a part of it.5 His marginalization reflected not only the sectarian tensions of the civil war, but also the exclusionary nature of the Christian-dominated art market, which largely distanced itself from politically charged narratives.

Visual analysis reveals stylistic and thematic elements in Molaeb’s works reminiscent of al-Hallaj. Both artists drew from overlapping struggles, including resistance to oppression and a shared cultural heritage, forging connections across geographic and ideological boundaries. Molaeb’s engagement with printmaking paralleled that of al-Hallaj, whose work addressed themes of displacement and resistance, rooted in his experiences as a Palestinian artist in exile. While Molaeb’s position as a leftist Druze in Lebanon brought its own complexities, both artists were deeply invested in depicting shared cultural and political themes.6 Their use of printmaking was not coincidental; rather, it reflected a broader engagement with visual culture during the war. Newspapers, war-themed prints, and political posters played a central role in shaping the visual environment of everyday life during political upheaval.

Taking Jamil Molaeb’s 1982 exhibition as a starting point, this article discusses what led to the production of prints during the civil war period. It argues that the themes of resistance and struggle, often expressed in war motifs, are closely tied to the aesthetics of printmaking and its links to other forms of visual culture. This is brought out further by an analysis of the aesthetic and ideological frameworks of the works of Mustafa al-Hallaj, whose presence in Beirut’s art scene will first be described. A comparison of both artists’ work shows how each was steeped in their own experience, despite aesthetic similarities, explaining their inscription into separate art worlds by some of their peers. Drawing on Zeina Maasri’s concept of “translocal visuality,” the paper contextualizes Molaeb’s work as part of a network of visual practices that crossed boundaries between fine art and popular imagery.7 Finally, the article demonstrates how the prints’ aesthetic connection to leftist graphic design shaped their reception. The linkage between printmaking and graphic design ultimately alienated this art genre from the largely bourgeois-dominated art market and forced artists and galleries to return to the more commercially viable mainstream art.8

Jamil Molaeb’s 1982 exhibition at the Galerie Épreuve d’Artiste unveiled an impressive collection of thirty-four etchings and twenty-three woodcuts. Not only did he display his prints on the gallery walls, but also presented a collection of their reproductions in an album with the eponymous title “The End of Darkness, the Beginning of Dawn,” with which he completed a trilogy of albums that documented life under the civil war. The previous two books contained compilations of drawings that directly referenced the war atrocities, expressed by graphic depictions and explicit titles, and were published and exhibited in 1977 and 1979 respectively. By the time Molaeb showed his woodcuts, he was already acclaimed in Lebanon’s art circles for his adeptness in various painting techniques. One critic praised him as a young talent who followed in the footsteps of established Lebanese colourists like Shafic Abboud (1926–2004), Elie Kanaan (1926–2009) and Amine El Bacha (1932–2019).9

The 1982 exhibition stood out in Molaeb’s repertoire, both in terms of technique and by showing a wider range of themes with less graphic violence. While it was reported as his debut in printmaking, the Lebanese press overlooked that he had already exhibited engravings almost a decade earlier. In 1973, Molaeb had held his first solo show in Algiers, where he had been studying at the Académie des Beaux Arts the same year. While he exhibited mainly watercolours and gouache, which thematically explored Andalusia and its Arab heritage, his Algiers show also included twenty-seven engravings that were met with interest.10 Prior to his studies in Algeria, he graduated from the Institute of Fine Arts at the Lebanese University, where he eventually became an art educator in 1977. At the beginning of his teaching career, he also managed the institute’s printmaking studio.11

By the time of the 1982 exhibition, Molaeb’s practice had evolved. Unlike his earlier depictions, which often portrayed the fight for collective struggle and the atrocities of the civil war’s early years, his woodcuts reflected a shift in narrative focus. The images in the third album no longer seemed to show war in its immediate cruelty as an active agent of aggression, but rather as the completed act of a narrative and its reverberating effects on people and society. The scenes vary from landscapes to urban settings, including bustling streets with details of wrecked vehicles, abandoned structures, militiamen with weapons, jammed traffic, lively cafés, and pedestrians.12

![Molaeb, Jamil. <i>Rasif al-taʿab</i> [Pavement of fatigue]. 1981. Woodcut print. 76 × 56 cm. From the series <i>Akhir al-zalam, awwal al-fajr</i>, published in 1982. Saradar Collection, Beirut. Courtesy of the artist.](https://bop.unibe.ch/manazir/article/download/11663/version/11963/15961/61809/pvsffh69p0ya.webp)

This shift is particularly evident in one of the woodcut prints exhibited, titled Pavement of Fatigue (fig. 1). The composition is divided into three horizontal sections, each showcasing a series of motifs. Most motifs are depicted in profile view, including cars, dogs, donkeys, feet, and hands. Some intriguing combinations are noticeable: feet with attached heads bearing weapons, positioned prominently at the print’s centre, clearly allude to militiamen on the streets. Surrounding them are an isolated hand and a foot, alongside piled-up cars and trees. On the far-right end, two heads with torsos emerge, holding guns in their hands. In the upper right corner, a group of figures sits atop an oversized chameleon, with the last figure facing the chameleon’s tail. The bottom section features two dogs, one with a white and the other with a black head, while the latter is equipped with three attached machine guns. They face the left edge of the print, confronting three similarly shaped objects resembling hand grenades. The woodcut’s partitioning into horizontal sections implies a narrative sequence. Yet, unlike a linear narrative, each section appears disjointed. As author and art critic Joseph Tarrab remarks:

[The sectioning] allows Molaeb to combine series of images that seem conjured up through free associations or, without associations at all, by sovereign decision. Although those effigies are in themselves perfectly meaningful in the overall context of the work, they sometimes seem enigmatically disparate, as if Molaeb, instead of making his thought explicit, were condensing it in rebus.13

This disjointedness reflects the complexities of the interwar and postwar periods and the aftermaths of intense armed conflicts, where realities were marked by fragmentation rather than coherence. The Lebanese Civil War was not a continuous conflict lasting from 1975 to 1990, but rather fragmented and unpredictable in reality. Periods of calm would spark hope that violence was over, only for fighting to resurge with greater intensity. This repeating cycle of relative calm and excessive violence created a sense of instability, as underlying tensions and grievances persisted, leaving the potential of re-emerging conflict high.

Consequently, the print’s motifs convey a sense of chaos and turmoil on the streets. The imagery of piled-up cars and isolated body parts reveals a landscape of destruction and disarray, while the figures holding guns underpin militia violence. The oversized chameleon hints at the surreal and unstable nature of war, where reality seems distorted. The figure facing the reptile’s tale suggests a sense of detachment from the chaotic world unfolding in the print. It seems almost like a metaphor for disturbed civilians who felt alienated from the events happening around them, and disillusioned by the brutality and destruction.

![Molaeb, Jamil. <i>Fi-ahdan al-wahda</i> [In the arms of loneliness]. 1981. Woodcut print. 76 × 56 cm. From the series <i>Akhir al-zalam, awwal al-fajr</i>, published in 1982. Saradar Collection, Beirut. Courtesy of the artist.](https://bop.unibe.ch/manazir/article/download/11663/version/11963/15961/61810/m8oljk9j471.webp)

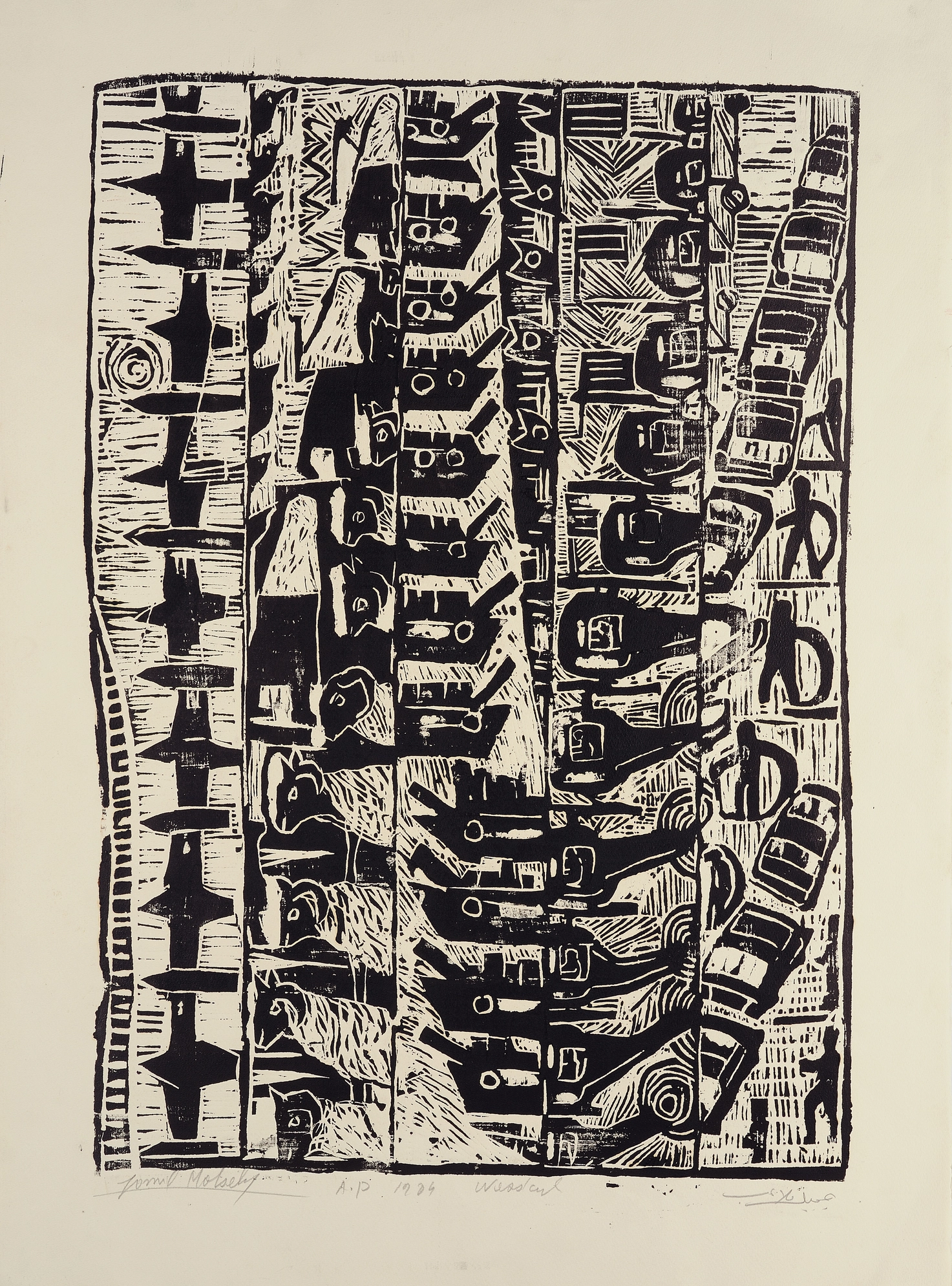

In the print In the Arms of Loneliness (fig. 2), similar features are visible. Compositions are densely filled in vertical panels and feature abstracted, stylized human figures and patterns. The spaces between the woodblocks create white lines segmenting the overall structure of the composition. The figures are carved in a simplified, almost primitive style and include men, women, and children. Rather than focusing on detailed features, the emphasis lies on the interplay between the positive and negative spaces. The figures are in different poses—sitting, standing, or kneeling—and are adorned with simple but repetitive patterns. Creating a rhythmic harmony, this feature connects the different sections of the artwork. However, upon closer inspection the artist’s depiction of village people becomes apparent, identifiable through their attire, likely representing a Druze village.

Regarding such woodcut motifs, Tarrab designates Molaeb as an “indigenous ethnographer” who “watches his familiar world with obvious affection and active sympathy, a world threatened by war, […] in order to perpetuate its memory through a graphic approach imbued with hieraticism and sometimes solemnity which ennobles and idealizes even the minor aspects of peasant life.”14 Throughout his artistic career, Molaeb was bound to the depiction of village life and nature that stemmed from his strong connection to his native village Baysour, which became his refuge during the intense days of the civil war years.

An interview of the artist explaining his approach and the reason why he chose woodcuts was featured in the local newspaper an-Nahar. While he did not describe the iconography of his motifs, he elaborated at length on the meaning of the colours black and white. Accordingly, white was the vitality of life that was carved into the severity of life, as reflected by the black wood blocks.15 Molaeb describes his approach as follows:

One point is enough to disturb the neutrality in [the print’s] area. There is no neutrality in my engravings. And so, I find my hand following it to the ends of its corners and the edges of its rectangles. Or is behind this rejection of whiteness a violent desire to say everything at once?16

In an article in L’Orient-Le Jour, Molaeb refers to these prints as “taqasim,” drawing a parallel to solo recitals in music.17 Just as in a solo recital where the performer takes centre stage and presents a programme of musical pieces, Molaeb offers his audience a focused experience on the abilities and artistry of the soloist. His “taqasim” are about life and death and perceived as depicting suffering and sorrow. Yet, as Molaeb describes, beauty is not limited to joy and happiness, and even the most desperate creation can be aesthetically pleasing when crafted with conviction. The journey through darkness holds value for the artist, who states, “after having lived through the darkness, which often is our common fate, I see more clearly.”18 He further explains his choice for this technique, contending that printmaking is not merely an expression, but rather a language.19 It was a mode of communication, ideally suited for the articulation of thoughts and sentiments during the times in which he lived.20

Molaeb’s art show drew mainly positive critique. Art critic Hassan Badaoui refers to the exhibition as the first of its kind in Lebanon. He adds in parentheses: “except for the Palestinian artist Mustafa al-Hallaj, who produced masonite prints, but is not considered part of the Lebanese art movement.”21 This intriguing statement led me to explore a series of Hallaj’s fine prints and poster prints, which will be discussed in the following sections.

In his accounts on Palestinian artists who lived in Beirut during the city’s cultural peak, Palestinian artist and writer Kamal Boullata (1942–2019) discusses the artistic contributions of the first generation of Palestinian refugee artists following the Nakba.22 He states that “Beirut may be invisible in the works of Palestinian artists who lived there for almost three consecutive decades.”23 He further asserts that, rather than drawing inspiration from the Lebanese environment, those artists were practising art in memory of Palestine. Based on these statements, the question arises to what extent Palestinian and Lebanese artists in Beirut inspired each other. Boullata’s account suggests that they practised their work detached from each other in parallel societies, strictly following nationalistic groupings and political ideologies.

Boullata further discusses al-Hallaj’s works in the context of two distinct groups of Palestinian artists in Beirut: those originating from refugee camps and those who were integrated into Beirut’s bourgeois artistic circles, referred to as “Ras Beirut artists.”24 Yet Boullata views Mustafa al-Hallaj, a “camp artist,” as an exception, as he was a trained artist who pursued a career in printmaking. His works were printed in multiple editions and known to a wide audience beyond the Lebanese borders. After his family was displaced from the Jaffa region in 1948, they moved first to Damascus then to a poor neighbourhood of Cairo, where he enrolled at the Academy of Fine Arts with the aim of becoming a sculptor—a career path he eventually dismissed. He then stuck to printmaking after moving to Beirut in 1974.25 He spent eight years in the Lebanese capital, until the Israeli invasion in 1982 that expelled the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) from Beirut and made life for Palestinian artists particularly difficult.26

Al-Hallaj’s works gained popularity in the Palestinian refugee camps, where his images were circulating. Coffee houses and streets were also covered by his posters and images that gained a wide reach.27 His prints, however, were not only distributed for cheap, targeting audiences with political messages. While Boullata asserted that “[a]rt from the camps never entered Beirut’s art market or commercial galleries,” al-Hallaj’s art did gain exposure within Beirut’s artistic circles, although largely on the margins of mainstream galleries. He participated in the International Art Exhibition for Palestine in 1978, for instance, held at the Arab University in West Beirut. The exhibition carried crucial political significance as support for the Palestinian cause and showed works composed as a collection for a Palestinian “museum in exile.”28 As a venue, the Arab University deliberately prioritized accessibility to a wide audience, underscoring the intersection of art and political activism. The inclusion of al-Hallaj’s work in an exhibition of this scope highlights his cultural and symbolic importance. Similarly, his solo show at the restaurant-cum-gallery Smuggler’s Inn in 1979 introduced his graphic works, including his woodcut prints, to a broader audience.29 As these venues were more accessible than mainstream galleries like the Galerie Épreuve d’Artiste, this illustrates the potential of al-Hallaj’s work to traverse political and artistic spaces.

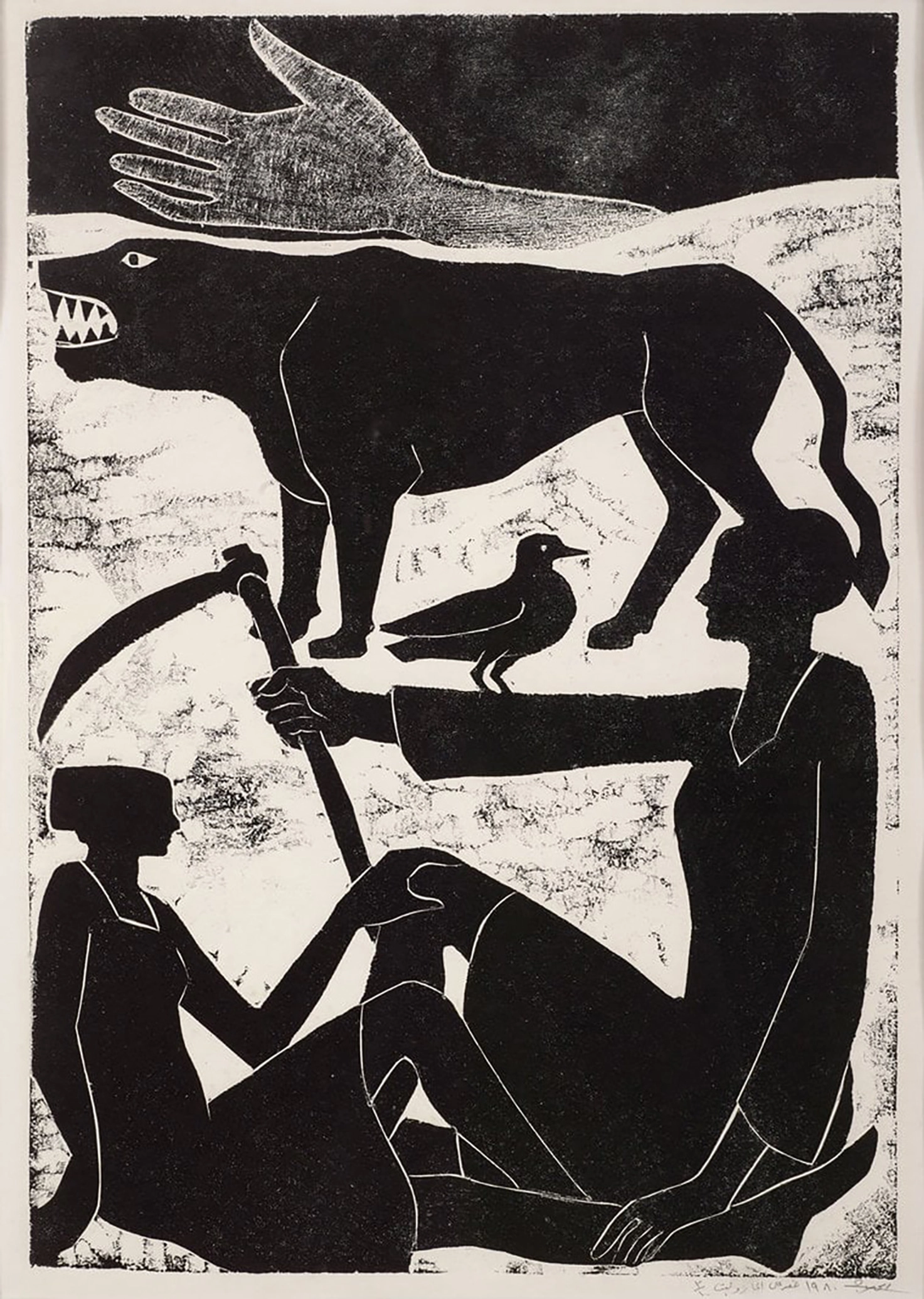

A sidebar note in L’Orient-Le Jour mentions that his works were even permanently hanging in the Planula-Elissar Gallery that was founded by George Zeenny, owner of the Smugglers’ Inn.30 One of his masonite engravings exhibited there, untitled like most of the artist’s works, is an apt example of al-Hallaj’s signature style, which often incorporates elements of mythology of ancient Near Eastern civilizations and folklore (fig. 3).31 In the composition, three layers of figures are depicted from the bottom to the top: in the foreground, two female figures are seated. The figure on the right, larger in size, holds a hoe in one hand with a raven perched on her outstretched arm. Her left hand gently rests on the other figure’s leg. Both figures interact in a familiar and mutually supportive manner. Above them looms a menacing-looking beast resembling wild predators with bared teeth. A large hand protrudes against the dark horizon in the background. The combination of these elements—the hoe, the raven, and the size of the figure—hint at the personification of the motherland defending and nurturing her people. Equipped with the tool of labour and the raven symbolizing a bad omen, she shields the opposite figure from the beast, which represents threats to her land and culture. Given al-Hallaj’s focus on themes of resistance within the context of the Palestinian struggle, this figure allegorizes the spirit of Palestinian resistance—deeply connected to the land and endowed with the foresight and strength to face adversities. Art historian Alessandra Amin characterizes his style as “animated by a sense of accumulation, of the layering of partial references to historical, mythological, and contemporary cultures within a realm of hallucinatory fantasy.”32

Another example among al-Hallaj’s prints is the depiction of a dynamic scene with multiple human figures and animals, aligned in a continuous narrative format.33 Arranged on a horizontal stripe, the composition guides the viewer’s eye from left to right due to a linear progression of stylized figures, indicating movement. On the left side, a group of human figures stands closely together, their bodies overlapping, depicting the community. Towards the centre, large figures are engaged in an act of combat, pointing their weapons to the right side of the composition. Behind them, a winged horse protrudes in forward motion, adding a mythical element to the scene. To the right, another, yet smaller, horse is depicted, with a human figure seated on its back, suggesting leadership and control. The figures’ limbs and bodies form a complex web of lines and shapes, instilling movement. The spaces between the figures are crafted with short, bold, and accentuated lines that create elaborate patterns. The boldness of these lines helps to define the contours of the figurative elements, making them stand out against the background. Al-Hallaj was known for his complex approach to printmaking. The technique of masonite engraving allows for stark, expressive lines and sharp contrasts, which are evident in this piece.

The textuality of the prints underscores the emotional and thematic intensity of the image. His works often include a rich variety of symbols, forming a powerful allegory of struggle, protection, and cultural endurance. They feature multiple themes to be explored simultaneously, each segment contributing a piece to the overall message. His prints were not produced for artistic reasons alone. He was one of the pioneering Palestinian graphic artists who was actively involved in the PLO’s cultural production.34 Indeed, he contributed to the “revolutionary aesthetic” in Palestinian poster design for Fatah and the PLO.35 These posters were widely recognized and influential within Fatah’s political publicity, especially in the late 1960s.

In Cosmopolitan Radicalism, Zeina Maasri investigates the “aesthetic emergence of Palestinian revolutionary struggle” by examining the “printscapes” reflecting Beirut’s public culture through the “circuits of artistic solidarity.”36 As Beirut emerged as a centre for the convergence of political and artistic influences, a distinctively formed visual culture, which the author labels as “translocal visuality,” effectively transformed the city into a symbol of Arab revolutionary identity. The author uses this term to define a “visual dimension of printed matter in transnational circuits of modernism and thus to account for: the movement of printed image-objects; artists, intellectuals and designers; and discourses about art and the realm of the visual, in its aesthetic dimension, as a force-field entangled with politics.”37 Maasri also voices critique over Boullata’s sharp contrasting of the camp vs. Ras Beirut artists. She suggests instead that “one has to look at the printed matter that circulated in between these spaces and navigated the frontiers that might otherwise separate them.”38 I would like to take Maasri’s approach one step further and explore how the visual culture that was formed in the 1960s continued to influence fine arts production into the 1980s. In the following, I will demonstrate how this aesthetics extended beyond Beirut’s “circuits of artistic solidarity” and entered commercial art spaces. Although I recognize the inherent differences in the forms of production and complexities in technicalities between fine art prints and posters, it is essential to explore their cultural narratives and semiotic impacts to understand the broader spectrum of visual expression. This approach allows for a critical examination of how different contexts and material conditions influence the reception and interpretation of art production. This exploration will provide a deeper understanding of the ways in which the revolutionary aesthetics of the 1960s were not confined to their original contexts but continued to resonate and find new expressions within the evolving art market of the early 1980s.

As Maasri accounts, the interplay between the artistic environment and political activism in Beirut facilitated the development of political posters as both an art form and a medium of political expression. Artists found an outlet for their creative practice that was not limited to commercial gallery spaces but had wider reach in the public realm. This was not confined to Palestinian and Lebanese artists, but included artists from other Arab countries as well.39 Mustafa al-Hallaj serves as a compelling example for artists living in Beirut at that time who had dual roles as graphic designers and artists. His works were well received and significantly inspired a group of committed artists in Beirut.40 His influence was notable even among those who had not personally seen his exhibitions, especially, as I argue, due to the widespread recognition of his designs for Fatah posters.

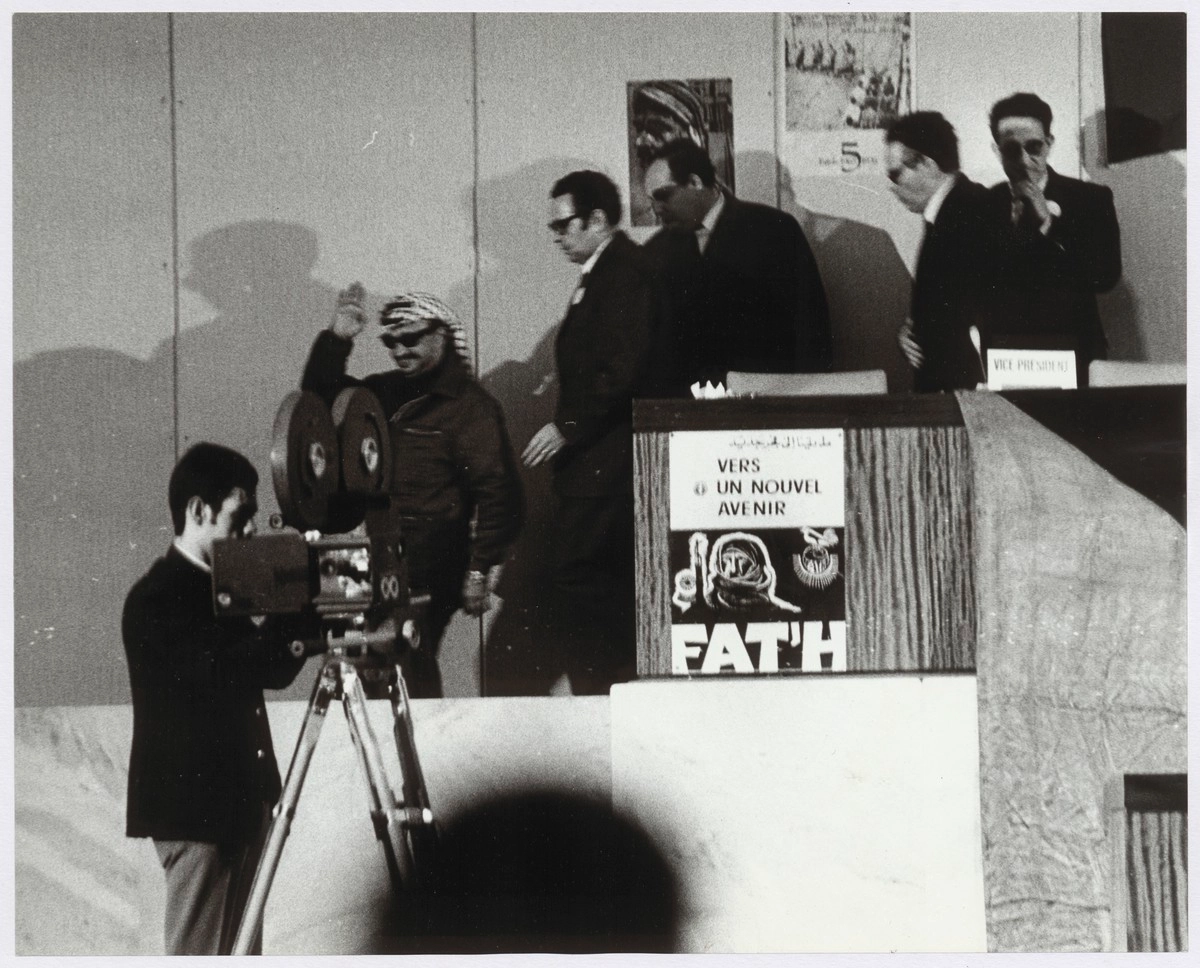

One of them will be discussed here.41 A photograph of al-Hallaj’s posters plastering the walls of a street in Algiers shows one of his designs that circulated the most. The central figure depicted is a fighter wearing a kuffiyah, a traditional Palestinian scarf. This identifies the figure as a representative icon of the Palestinian guerrilla fighter, known as fida’i.42 In the bottom section “Fat’h” (Fatah) is named. The top section features the slogan “towards a new future” in both French and Arabic. This poster, initially a woodcut print, subtly embodies some characteristics of al-Hallaj’s overall style, although it may not be immediately apparent. The name “Fat’h” is prominently displayed in white on a black background, occupying a quarter of the page. The image portion features an engraved guerrilla figure, emphasized by a strong contour line. To the right of him is a small, stylized bird depicted on a sphere, symbolizing a peace dove. Inside the sphere the name “Fat’h” is repeated. This dark section sharply contrasts with the upper third, where the slogan is positioned. The stark black and white contrasts seen in al-Hallaj’s posters create visual impact and immediate readability, necessary for the communicative function of the message. Contrast remains a key element in his non-political pieces as well, where it serves to highlight emotional depth or to draw attention to specific elements within the composition. The dramatic interplay of light and shadow thus hints at underlying psychological tension. As previously shown, in his artistic prints, al-Hallaj often segmented his compositions to create a layered narrative. Equally in his posters, each segment focuses on a specific element of the message: the identity of the movement, the goals, and the symbolic representation of the struggle.

The inclusion of a foreign language, however, reveals that this poster was aimed at an international audience, particularly in French-speaking countries, to garner support and raise awareness for the Palestinian cause. This poster was designed at the time when Fatah participated in the first Pan-African Festival in July 1969 in Algiers, advocating for the Palestinian struggle. The photograph of the poster stands as one of the best-known examples of mass communication from that era. The repetition and saturation of the images on the wall highlight the urgent way these visuals communicated with their surroundings. Not only the slogans, but the entire visuality—the unity between image and text, almost forming a pattern that seems to extend infinitely in a chain of patterns—leave a powerful impression.

Posters became a visual staple for residents of politically charged cities like Beirut and Algiers, as “graphic signs and political rhetoric of posters became a prevalent sign/reading that shaped the cityscape.”43 Not only were al-Hallaj’s posters visible for audiences on the streets of Arab cities but also to a broader readership of global newspapers, as one press photo from the Fatah conference at the Palais des Nations in Algiers in December 1969 testifies (fig. 4). These posters were reproduced in news articles and transcended their initial context. The original poster, intended for regional impact, gains new dimensions when it is photographed and published in global news media. This act of recontextualization transformed the poster from a static piece of street art into a dynamic symbol within international discourse. Each reproduction not only carried but also amplified its semiotic power, embedding it deeper into a collective consciousness.

In Beirut, al-Hallaj’s atelier was situated in Hamra, a vibrant political and cultural neighbourhood. He likely interacted with local artists who were sympathizing with leftist parties and were politically engaged in anti-imperialist movements, socialist agendas, cultural policies, and the Palestinian cause.44 There was a nucleus of Lebanese artists committed to these causes, who were closely associated with the Lebanese University.45 The first generation of art educators were key in the development of the university’s Institute of Fine Arts, and were guiding their students not only in terms of art education but also on socio-political matters.46 Collaborations of artists created a broader network of political and artistic commitment in Beirut’s intellectual circles during the wartime period, linking personalities from the cultural milieu.47 This sense of comradery and social solidarity during his time as an art teacher is described by Jamil Molaeb in his dissertation:

In 1978, artists and art teachers introduced new ideas to change the political situation and stop the war. They showed and talked about their ideological concerns. Students responded to their work in school, by organizing art demonstrations, participating in festivals, supporting theater presentations, and making sculptures. Collections of some artists’ works were published in books between 1977–1979. These books expressed the civil war.48

In support of this assertion, Jamil Molaeb articulates how pivotal historical events, such as the Lebanon Crisis of 1958 and the Arab-Israeli War of 1967, fostered a significant shift in the landscape of Lebanese fine arts. His observation stresses how these events served as a force for the evolution of artistic expression, prompting artists to engage more deeply with socio-political themes.49 By stating that Lebanese fine arts gained from other art sources such as poetry, theatre, and politics, Molaeb suggests that these interdisciplinary influences enriched and expanded the scope of artistic practice. The expression in diverse artistic forms allowed for a more holistic and nuanced exploration of social and political issues. This led to the promotion of a stronger engagement and expression within the artistic community. After the 1967 war in particular, fine arts began to reflect and to express a social and political consciousness.50 This insight underscores the profound impact of these events on the trajectory of artistic expression. The heightened social and political awareness within the artistic community did not just appear with the beginning of the civil war but was a continuation of such practices from the unsteady prewar period. This commitment not only unified a group of Lebanese artists with the same socio-political views, but also facilitated connections with non-Lebanese peers, especially Palestinians, who shared similar aspirations. Through these connections, artists from Lebanon and Palestine collaborated, exchanging ideas and forging strong bonds of solidarity and mutual support.51 Under the guidance of influential mentors like Aref El Rayess, Jamil Molaeb, Moussa Tiba, and Seta Manoukian, this collective dedication to social and political commentary flourished. Their participation in events such as the International Art Exhibition for Palestine in 1978 further solidified their shared vision to use art as a platform for activism and solidarity with Palestinian artists, like Mustafa al-Hallaj.52

In this regard, Jamil Molaeb expressed his respect for al-Hallaj, acknowledging him positively among his peers.53 Yet, in his writings, Molaeb primarily credits Lebanese artists like Aref El Rayess and Rafic Charaf as inspirations.54 He mentions his participation in the 1978 exhibition at the Beirut Arab University, but omits connections to Beirut-based Palestinian artists, despite exhibiting alongside al-Hallaj in the same show. This highlights the discrepancy in writings and interviews by artists and critics from that time, who—unless it is for the same cause—clearly distinguish between a “Lebanese art movement” and a “Palestinian art movement.”55 This distinction is tied to the broader context of the Lebanese Civil War and the political role Palestinians played within it. The presence of the PLO in Lebanon, particularly after the 1967 Arab-Israeli War and the events of Black September in 1970, positioned Palestinian factions at the heart of leftist resistance movements. Their crucial involvement in the civil strife, especially against Lebanese nationalist and right-wing factions, tightened political tensions. Many Palestinian artists in Beirut were engaged in these leftist movements. Their involvement, however, came at the cost of being outcast from the art world and the mainstream galleries. Cultural institutions, particularly those aligned with more nationalist or conservative ideologies, often hesitated to showcase their work. As a result, politically motivated spaces became the only platform for most Palestinian artists, such as the 1978 exhibition, where art was explicitly framed as an act of resistance. The lack of acknowledgement of Palestinian artists in Lebanese artistic narratives, as seen in this example, reflects these broader divisions—where solidarity existed in practice, but historical memory and institutional frameworks often reinforced national and political separations.

This is why the Lebanese Civil War, a shared experience among local artists in Beirut, did not contribute to a unified local artistic identity. The divergent perspectives underscore the distinct national and political contexts shaping each movement. Art critic Hassan Badaoui’s praise of Molaeb’s prints as “new, advanced, and unique stages in the Lebanese artistic movement” starkly emphasizes the fragmented identities elicited by such divisive influences.56 Yet, this nationalistic lens obscures the broader impacts of the civil war on artistic expressions.

Looking at both artists’ works, similarities are prevalent not only in the use of black-and-white images, but also in the narrative representation, figurative subjects with allegorical associations, and symbolic expressions. Al-Hallaj’s artworks were primarily black-and-white woodcut prints. His themes are narrative and depict figurative subjects that convey allegorical meanings with surreal features. Human figures of various sizes are recurring elements in his compositions, seemingly floating and surrounded by a mysterious, dreamlike environment. They are often accompanied by horses, roosters, and mythical creatures. His figures are marked by their flatness, with limited details outlined by simple contours and put in a narrative succession.57 Comparable characteristics are featured in Molaeb’s works that illustrate the chaotic and surreal nature of the war-torn environment. Marked by a profound narrative depth, his work offers visual snapshots by critically analysing the impact of war. Visual analysis of both artists’ works has shown how, despite their technical and aesthetic similarities, each is deeply rooted in their own context. For Molaeb, depicting the war required a certain aesthetic that was inherently shaped by the politically charged, realistic, and graphic visuality present in the artist’s environment.

Molaeb continued to work on similar themes in woodcut prints throughout his career, although his focus on prints decreased in favour of more abstract compositions and media of painting. In 1984, the artist obtained a scholarship and deepened his knowledge in printmaking at the Pratt Institute in New York. One of his prints from the same year shows a more intensified expression and denser composition as opposed to the prints of the third album (fig. 5). This composition almost seems to be a culmination of his own artistic evolution, mingled with inspiration from the visual chaos and patterns found in the urban environment. The layering of posters, graffiti, and other street art elements can inform the creation of complex, textured artworks. Molaeb’s fierce repetition of the same motif in each strip, sequenced in a series of stripes, evokes the fleeting impression of a wall littered with posters, which we glimpse momentarily as we pass by. The circulation of a politically charged visual culture leverages the interaction between public messages and artistic expression, leading to new forms of abstract art that reflect societal influences.

This politically charged imagery is further reflected in Molaeb’s approach, which he explains in light of the civil war:

The social conditions that we went through back then were not that different from today’s. But there was also danger, surprises, and explosions. I expressed all these things at the time in a mythical way or in the Sumerian tradition of stonecutting or the Egyptian hieroglyphic writing. I tried being myself because we all carry within ourselves a lot of cultures. I wanted to treat these works as if I were an ancient artist.58

This places him within the broader context of Arab artists who revisited ancient art forms from their regions, as did al-Hallaj, who drew on Egyptian folklore and ancient relief carvings and “appropriated suggestive symbols to eulogize the Palestinian martyr.”59 This approach carried an anti-imperialist dimension, utilizing regional artistic traditions—both ancient and vernacular—as means to assert cultural identity and heritage in the face of historical and contemporary western influence and imperialism. This was one of the reasons why Molaeb chose to study in Algeria at the time, instead of pursuing a European education.60 His engagement with allegedly ancient Arab artistic traditions was more of a political act in the context of regional conflicts than a stylistic or historical decision. The emphasis on Arabness, especially through references to ancient civilizations, served as a counter-narrative to right-wing parties propagating a Phoenician identity.

In his review of Jamil Molaeb’s 1973 Algiers exhibition, art critic Mekhelef addresses Molaeb’s deeply rooted Arab identity and political views. He emphasizes how Molaeb’s political awareness reinforced his connection to Arab heritage and shaped his artistic expression. His education and exposure to masterpieces in the countries of their origin led him to believe that many such works were inspired by earlier Arab creations, as Mekhelef further accounts. This belief was particularly influenced during his time in Algeria, where his political identity as an Arab was strongly formed. Armed conflicts were since then reflected in his works. The use of spare lines, as the critic continues, conveyed intense emotional depth, while stylized characters depicted a continual struggle for justice in face of the challenges of technological civilization.61 Although these observations refer to his early work, Molaeb later returned to similar visual strategies during the Lebanese Civil War, when such visual adoptions were also employed by numerous artists who created political posters, addressing cultural sentiments and a sense of belonging.62

The impact of Beirut’s public visual culture on Molaeb’s art, also shaped through graffiti scribblings and drawings, was already evident in his previous two albums.63 The raw brutality of civil strife was vividly portrayed by anthropomorphic figures engaged in acts of torture and assault (fig. 6). Molaeb’s use of stark, sharp contours in black-and-white ink and watercolour dramatically amplified the ferocity of the scenes. In the second book, the compositions grew more crowded, marked by endless repetitions of figures and elements that took on an almost ornamental quality. These works reached a broad audience due to their reproductions in albums.

![Molaeb, Jamil. <i>Akbiat al Taazib</i> [Underground torture]. 1976. Around 34 × 44 cm. From the series <i>Daftar al-harb al-ahliyyah, 1975–1976</i>. Saradar Collection, Beirut. Courtesy of the Artist.](https://bop.unibe.ch/manazir/article/download/11663/version/11963/15961/61814/vpum1iuqsasj.webp)

The flatness of figures depicted in sharp contours, especially in the first album of drawings are referred to as “child-like” renderings by local reviewers.64 Art critic Fayçal Sultan saw the production of drawings as an “emergence of a realistic artistic current that depicts with tragic precision the convulsions of emotions in catastrophic times […] an artistic current whose features we have seen in the production of more than one artist, Lebanese and Arab, and whose first start among us was known in the works of Aref El Rayess since his exhibition (Black and White).”65 Aref El Rayess, both colleague and mentor to Jamil Molaeb, was not only a politically engaged artist but also a dedicated chronicler of wars.66 He wrote, alongside art critic and calligrapher Samir Sayegh, the introduction to Molaeb’s inaugural book, where he underscored the paramount importance of art in reflecting the socio-political landscape of war.67 He firmly articulated that true creativity and originality in artistic endeavours could only be attained through an honest confrontation with the visual realities of conflict, a sentiment graphically echoed in Molaeb’s works. By advocating for the social role of art, he celebrated Molaeb’s artistic testimony.68

The connection between drawings and the practice of printmaking, however, extends beyond mere visual similarities; it delves into the profound significance of these media as coping mechanisms and documentation tools for artists grappling with the realities of conflict. For Jamil Molaeb, drawings initially provided a means of expression, yet he eventually found them insufficient for capturing the full depth of his experiences. Turning to the medium of woodcut prints, he sought to convey the gravity of war with greater forcefulness. This urgency transcended the visual realm, manifesting in the physicality of the medium itself. The process of carving woodblocks became a cathartic experience, as the repetitive motions it required provided an outlet for pent-up emotions. Beyond its personal significance, printmaking has historically carried a clear political dimension. Embraced by leftist artists worldwide, prints were used widely in revolutionary movements due to their accessibility, affordability, and reproducibility. By using this medium, Molaeb aligned himself with a long tradition of socially engaged art, reinforcing a broader ideological stance in his work. From carving to labour-intensive hand printing, every step in the process demanded patience and strength.69 The artist linked his creative practice with the harsh reality by limiting the colour palette to black and white. What unifies drawings and prints is their graphic visuality, evident in both expression and motifs, and their accessibility outside traditional commercial structures, setting them apart within the Lebanese art scene of that era.

Yet, Jamil Molaeb’s 1982 print exhibition presents a novel approach to promoting the social role of art, distinct from his earlier drawings. By reproducing fine prints in an album, he aimed to engage a broader audience beyond traditional buyers and collectors. Selling his original works in a commercial gallery at the same time underscores his effort to merge local artistic values with broader art market dynamics, thereby introducing “translocal visuality” into the commercial realm. Unlike his first two books, Molaeb carefully catalogued these works by number, title, dimensions, and techniques, demonstrating a strategic engagement with the art market that might not be immediately apparent. In the Lebanese context, obtaining titles or details about techniques and dimensions remains challenging. Even primary sources from various gallery archives, including the Galerie Épreuve d’Artiste’s, often lack such information. This suggests that the artworks’ social impact is manifested through Jamil Molaeb’s deliberate approach to educate and connect with various audiences.

In his dissertation, Molaeb quotes an interview of art teachers at the Lebanese University regarding the representation of war in Lebanese art. In it, artist and art teacher Rafic Charaf acknowledges the limited portrayal of the war in traditional media like oil painting, contrasting it with the more prevalent and impactful depictions found in posters, gouache pictures, and other popular forms of art. Charaf suggests that oil painting, often seen as academic and individualistic, tended to convey a sense of isolation and division, drawing on personal memories and imagination. He argues that media like photography, film, broadcasting, and posters, however, were more effective in capturing the essence of the war due to their immediacy and accessibility to a wider audience. Charaf proposes that the war is a rich subject for artistic exploration, particularly suited for media like movies and theatre, which can convey its complexity and historical significance more forcefully.70 These insights show how the choice of artistic media in depicting war was reflected on by artists at the time.

Jamil Molaeb strategically embraced the use of prints, recognizing that traditional painting media often lacked the immediacy and communal resonance required to authentically convey the intense and multifaceted nature of war. Printmaking techniques were more suitable for both the transmission of “translocal visuality” and expression of the urgent and compelling nature of the war. Hence, Molaeb chose prints as a medium to bridge the gap between the fine arts and the collective engagement of political motifs. This choice allowed him not only to explore the complexities of war but also to amplify socio-political messaging through the accessible and distributable form of prints, ensuring a broader impact and deeper public reflection on the themes he depicted.

Although similarities in the visual language between al-Hallaj and Molaeb have been noted, it needs to be stressed that Molaeb’s works stand in their own unique and local context. While al-Hallaj’s figures are placed in an allegorical world, Molaeb situates his figures within the Lebanese context, whether it is Beirut or Lebanese villages, including his own. The events are tied to a specific location and, despite surreal suggestions, remain clearly definable. The scenes capture multiple aspects of life during the war and give insights into the memories and emotions of a war-torn society, revealing fears, fragmentation, and resilience.

Perhaps it is precisely this context that was too direct, too immediate for the audience, who could not process their experiences in the same way Molaeb did through his physical externalization of trauma into woodcuts. Addressing the war’s profound impact extends beyond artistic output to the very fabric of cultural infrastructure and daily life, shaping artists’ modes of expression and shifts in the decisions of gallery owners and collectors.

In the 1980s, galleries predominantly favoured art forms considered mainstream art, adhering closely to established paradigms of “high art.” Amidst this conformity, subtle developments unfurled: the war itself remained conspicuously absent from artistic discourse, with few exceptions such as Molaeb’s exhibition. While his prints resonated with critics, they faced challenges within the commercial art market. The Galerie Épreuve d’Artiste was one of very few platforms where war themes were shown at that time. Given the task to fill a gap in the gallery landscape in terms of quantity and “quality,” as stated by co-founder Amal Traboulsi, the gallerists were seeking works of artists who were tackling social topics and were less concerned about appealing aesthetics.71 Yet, as the further trajectories of both the artist and the gallery show, fewer print shows were hosted by the owners who eventually had to comply with the audience’s preferences for paintings, especially works in watercolour. This development may have been supported by the fact that prints resonated too closely with the ongoing realities of war.

Towards the end of the war, mainstream art dominated exhibitions, indicating a market that stuck to more traditional forms. Despite initial efforts by galleries to challenge this status quo, these attempts failed to sustain momentum. As a result, Molaeb limited the number of prints that he exhibited in Beiruti circles.72 This analysis underscores that certain aesthetics, particularly those associated with immediate socio-political issues, struggle to find acceptance and hence marketability within certain temporal contexts.

In this regard, examining Molaeb’s artistic trajectory alongside that of al-Hallaj provides a deeper understanding of how war, political struggle, and artistic media intersected across different contexts. The artistic conversation between Molaeb and al-Hallaj underscores the profound interconnectedness of regional artists, who shared and reshaped each other’s visual languages in response to armed conflicts. Yet, beyond their aesthetic similarities, juxtaposing their works highlights how different political and national contexts shaped the role of artistic expressions of war. While al-Hallaj’s prints engaged with Palestinian resistance through allegorical imagery, Molaeb’s woodcuts reflected the immediate realities of the Lebanese Civil War. This comparison not only demonstrates how war informed visual expression across borders but also challenges rigid distinctions between Lebanese and Palestinian artistic movements, revealing a deeper network of solidarity, influence, and shared struggles.

This research was partly conducted in the context of the research project Lebanon’s Art World at Home and Abroad (LAWHA), which has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 850760).

Ali, Wijdan. Modern Islamic Art: Development and Continuity. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1997.

Amin, Alessandra. “Mustafa El Hallaj, Palestine (1938–2002).” Dalloul Art Foundation Beirut. Accessed 10 April 2024. https://dafbeirut.org/en/mustafa-el-hallaj.

Bacho, Ginane Makki, and Nasser Soumi. Interviews by author, October 2022.

Badaoui, Hassan. “Fannan yahfir bi-l-khashab, wa-yatbaʿ, fa-yarfaʿ al-hiyad ʿan-al-misaha al-baydaʾ.” Al-Liwa’, 7 February 1982.

Boullata, Kamal. “Artists Re-member Palestine in Beirut.” Journal of Palestine Studies 32, no. 4 (2003): 22–38. https://doi.org/10.1525/jps.2003.32.4.22.

Boullata, Kamal. Palestinian Art: 1850–2005. London: Saqi, 2009.

Chakhtoura, Maria. Liban 1975–1978: La guerre des graffiti. Beirut: Éditions Dar An-Nahar, 1978.

“Daftar al-harb al-ahliyya yarsum al-jahim munzawiyan, mukhtabiʾan, waraʾ shajara!” Al-Kifah Al-Arabi, 10 October 1977.

El Rayess, Aref. “Al-muqaddima.” Daftar al-harb al-ahliyyah, 1976, n.p.

Fakhoury, Bushra. “Art Education in Lebanon.” PhD diss., University of London, 1983.

Gasparian, Natasha. Commitment in the Artistic Practice of Aref El-Rayess: The Changing of Horses. London: Anthem Press, 2020.

Halaby, Samia. “Mustafa al-Hallaj: Master of the Print and Master of Ceremonies.” Jadaliyya, 31 May 2013. https://www.jadaliyya.com/Details/28691.

International Art Exhibition for Palestine. Beirut: PLO Unified Information Office, 1978. Catalogue of an exhibition held at the Beirut Arab University, Beirut, 21 March–5 April 1978.

Khouri, Kristine, and Rasha Salti. Past Disquiet: Artists, International Solidarity and Museums in Exile. Warsaw: Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw, 2018.

L’Orient-Le Jour, 15 May 1981, 4. Sidebar.

Maasri, Zeina. Cosmopolitan Radicalism: The Visual Politics of Beirut’s Global Sixties. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020.

Maasri, Zeina. Off the Wall: Political Posters of the Lebanese Civil War. London: I. B. Tauris, 2009.

Makarem, May. “Lawhat Jamil Molaeb, Mohammad al-Kaissi, Husayn Jumʿ a: Infitah basari wa-ghazarat ʿ ain wa-tajrubat infial.” An-Nahar, 1 March 1981.

Malusardi, Flavia Elena. “Committed Cultural Politics in Global 1960s Beirut: National Identity Making at Dar el Fan.” Biens Symboliques / Symbolic Goods 15 (2024): n.p. https://doi.org/10.4000/13kxy.

Matar, Dina. “PLO Cultural Activism: Mediating Liberation Aesthetics in Revolutionary Contexts.” Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East 38, no. 2 (2018): 354–64. https://doi.org/10.1215/1089201x-6982123.

Mekhelef, A. Review of Jamil Molaeb exhibition, Algiers, 1973. Al-Ahdath, 25 February 1973, n.p.

“‘Mes gravures sont des Takassim’ sur la vie et la mort.” L’Orient-Le Jour, 3 February 1982, n.p.

Molaeb, Jamil. “Artists and Art Education in Time of War: Lebanon.” PhD. diss., Ohio State University, 1989.

Molaeb, Jamil. “Jamil Molaeb haffar fi-kitab ‘li-arfaʿ al-hiyad ʿ an-al-misaha’.” An-Nahar, 30 January 1982, n.p.

Molaeb, Jamil. “Muqaddima.” Akhir al-zalam, awwal al-fajr, 1982, n.p.

Naef, Silvia. À la recherche d’une modernité arabe: L’évolution des arts plastiques en Egypte, au Liban et en Irak. Geneva: Slatkine, 1996.

Nammour, César. Amam al-lawha: Kitabat fī-l-rasm. Beirut: Dar al-Funun al-Jamila, 2003.

Nammour, César. Naht fī-Lubnan. Beirut: Dar al-Funun al-Jamila, 1990.

Roz, Wafa. “Fine Arts Education in Lebanon: Part 1.” Dalloul Art Foundation Beirut. Accessed March 2023. https://dafbeirut.org/en/articles/Fine-Arts-Education-in-Lebanon-Part-1.

Roz, Wafa. “Fine Arts Education in Lebanon: Part 2.” Dalloul Art Foundation Beirut. Accessed March 2023. https://dafbeirut.org/en/articles/Fine-Arts-Education-in-Lebanon-Part-2.

Salamé Abillama, Nour, and Marie Tomb, eds. Art from Lebanon: Modern and Contemporary Artists. 1880–1975, vol. 1. Beirut: Wonderful Editions, 2012. Catalogue of an exhibition held at the Beirut Exhibition Center, Beirut, 25 October–9 December 2012.

Saradar Collection. “Words on Works: Woodcuts by Jamil Molaeb.” YouTube, 13 September 2017, video, 4:45. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B9pkLECVChA.

Soumi, Nasser, and Amal Traboulsi. Interview by author, October 2022.

Sultan, Fayçal. “Jamil Molaeb… ‘qariban min al-watan’: banurama mashhuna bi-l-tafasil.” As-Safir, 10 April 1979, n.p.

Tarrab, Joseph. Jamil Molaeb: Xylographies, Woodcuts, 1980–2014. Beirut: Les Éditions L’Orient-Le Jour, 2014.

The British Lebanese Association, ed. Lebanon: The Artist’s View. 200 Years of Lebanese Painting. London: Hillingdon Press, 1989. Catalogue of an exhibition held at the Barbican Centre, London, 18 April–2 June 1989.

Traboulsi, Amal. Interview by author, Beirut, 14 October 2022.

Traboulsi, Fawwaz. A Modern History of Lebanon. London: Pluto Press, 2012.

“Un doublé d’accrochages.” L’Orient-Le Jour, 15 May 1981, 4.