During the upheaval of the early civil war months in Lebanon in 1975, Mona Hatoum (b. 1952) found herself stranded in London, where she decided to study art. In the early 1980s, she graduated from the Slade School of Art, where she immersed herself in postmodern thought and the concurrent development of critical theory in the United Kingdom. Inspired by artistic movements challenging the norms of contemporary British art, she shaped her artistic approach by blending the artistic, social, and political realms. The ideas of Rasheed Araeen gave her a conceptual framework, exploring his reflections on Third World art, postcolonialism, questions of identity, and the notion of “black artist” in the United Kingdom. This article aims to examine Hatoum’s involvement in British Black Arts through her activities with Rasheed Araeen, presenting a fresh analysis of key works that assess their critical impact. While she is now a globally recognized artist, there has been limited research dedicated to the phase of her life when she existed on the fringes of art history during her youth in Beirut, then working in the then-contested field of performance and video, and often being considered a migrant artist, or as she once wrote: a black one. Drawing from an exclusive interview with the artist, this article offers an intersectional approach to both western art history and that from the SWANA (Southwest Asia and North Africa) region, shedding new light on this crucial period in her artistic development and its broader implications for understanding diverse artistic narratives.

Mona Hatoum, British Black Arts, Third World, Third Text, Rasheed Araeen

This article was received on 16 December 2024, double-blind peer-reviewed, and published on 17 December 2025 as part of Manazir Journal vol. 7 (2025): “Defying the Violence: Lebanon’s Visual Arts in the 1980s” edited by Nadia von Maltzahn.

Long ignored by canonical art history, artists associated with the British Black Arts movement have gained significant visibility in scholarship since the early 2000s.1 Emerging as a deliberate political project during the Thatcher years (1979–90) in the aftermath of widespread civil unrest across British metropolitan centres, this movement erupted onto the cultural landscape with unprecedented intellectual force.2 Encompassing artists of Caribbean, African, and Asian heritage working throughout the United Kingdom (UK), the movement was profoundly influenced by post-civil rights, Black Power movements in the United States of America and anti-apartheid activism in South Africa—such as BLK Arts Group and Pan-Afrikan Connection3—and retrospectively by cultural theorist Stuart Hall’s pioneering work on race and media representation.4 They systematically challenged imperial paradigms within institutional frameworks, fundamentally transforming both the constitution and perception of British cultural identity in enduring ways.

The British Black Arts movement was not a unified entity but rather a heterogeneous collective with multiple leaders and divergent strands. Its historiography consequently presents a complex tapestry. Early accounts on the movement were authored by active participants such as Eddie Chambers (b. 1960), Lubaina Himid (b. 1954), Maud Saulter (1960–2008) and Rasheed Araeen (b. 1935). These protagonists-artists-historians began documenting and theorizing their collective struggles even before the conclusion of the decade in which they emerged, establishing contemporaneous frameworks that have shaped subsequent scholarly discourses.

This article employs a microhistorical approach to excavate Mona Hatoum’s overlooked connections to this movement, constructing an alternative narrative that challenges her relegation to the periphery in canonical accounts. While her Palestinian and Lebanese roots are frequently discussed, what remains underexamined is that she once identified as a black artist and was affiliated with the British Black Arts movement in 1980s London. How did Hatoum’s encounter with Araeen—and his conceptualization of British Black Arts as a politically charged, anti-imperialist framework—give her a conceptual framework and nurture her artistic trajectory? To what extent did she embrace this affiliation and how did it influence her subsequent practice?

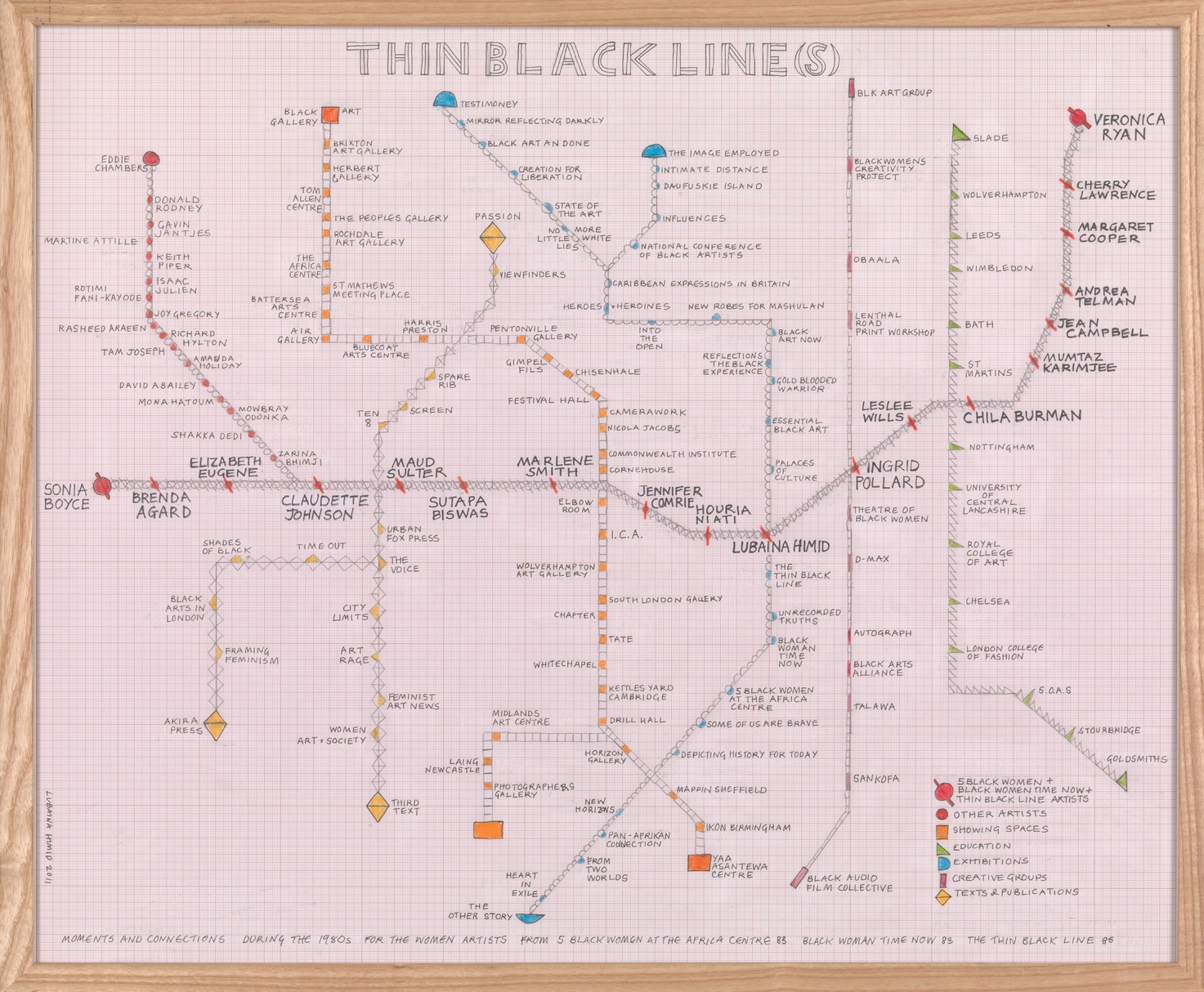

Lubaina Himid’s drawing Thin Black Line(s): Moments and Connections (2011) offers a revelatory entry point for this investigation (fig. 1). Resembling the London Underground map, this visual cartography catalogues the interconnected artists, institutions, exhibitions, and publications that constituted the movement’s ecosystem. Himid organizes these connections specifically around women artists’ movements between 1983 and 1985, centring figures like Sonia Boyce (b. 1962), Claudette Johnson (b. 1959), Maud Sulter (1960–2008), Houria Niati (b. 1948), Ingrid Pollard (b. 1953), and herself while displacing male-dominated histories to the margins. Significantly, Hatoum appears along what Himid labels the “Other Artists” tube line—a secondary trajectory alongside figures like Isaac Julien (b. 1960) and Keith Piper (b. 1960), positioned between David A. Bailey (b. 1961), Mowbray Odonkor (b. 1962), and Rasheed Araeen, to the upper left of the drawing.5

This marginalized positioning merits deeper investigation, particularly given Hatoum’s own acknowledgement of Araeen’s influence. When asked about the politicizing of her cultural difference, she responded: “When I met Rasheed Araeen in the mid-1980s, it was a revelation. He was someone who had rationalized and theorized issues of Otherness.”6 This connection is crucial for understanding Hatoum’s engagement with concepts of “Third World arts” and postcolonialism during this formative period.

Araeen’s conceptual framework and activist practice profoundly reshaped discourses on art in postwar Britain through multiple channels: conceptual art, critical writing, exhibition curation, and editorial work on journals like Black Phoenix (1978–79) and Third Text (since 1987). His strategic redefinition of “black”7—as well as the proposition of the term “Afro-Asian” which emerged from grass-roots black and South Asian political organizing in the 1970s—as a political rather than racial designation created a form of collective resistance encompassing individuals from the Global South who shared experiences of colonial subjugation and cultural marginalization.8 Simultaneously, he critiqued institutional approaches that confined black artists within an “imposed otherness” or tokenistic multiculturalism.9

This article begins by examining Hatoum’s formative experiences in 1970s Beirut before focusing on her art education in London—a crucial period that shaped both her aesthetic approach and political consciousness. Through analysing her participation in key exhibitions, publications, and networks associated with the British Black Arts movement—coupled with an exclusive interview with the artist centring on these formative times of her life10—I will demonstrate how Hatoum’s artistic path intersected with and diverged from its central concerns. The paper challenges simplified narratives about her artistic development, revealing instead a transnational trajectory where her practice evolved through dialogue across diverse geographic, cultural, and conceptual contexts—ultimately resisting the very categorizations that have marginalized her contribution to this significant moment in various nationalistic and nationalist art histories.

Mona Hatoum’s artistic identity emerges from multiple displacements, making her work a powerful meditation on belonging and exile that would later distinguish her from many British black artists. Born in 1952 to Palestinian parents who had fled Haifa during the 1948 Nakba, Hatoum grew up in Beirut with the peculiar status of having a British passport through her father’s employment with the British administration, yet never obtaining Lebanese citizenship. This early experience of existing between identities—Palestinian by heritage, Lebanese by upbringing, British by documentation, woman by gender binary—established themes of displacement and belonging that would become central to her artistic practice and differentiate her approach within British art circles.

Pre-civil war Beirut of the early 1970s provided Hatoum with an active artistic environment that shaped her later engagement with art in the UK. While often mythologized as merely a Mediterranean playground for the wealthy, Beirut harboured a sophisticated cultural scene documented by figures like Waddah Faris (1940–2024), whose photographs captured Hatoum at twenty-one during the 1973 Baalbek Festival (fig. 2)11—a moment when she stood at the threshold of her artistic journey.

Hatoum herself described this period as artistically vibrant. Beirut boasted half a dozen new galleries showcasing both local and international contemporary art.12 The Contact Gallery in Hamra, co-founded by Faris, became particularly significant in Hatoum’s artistic formation. As an experimental space showcasing both local and international contemporary art, it exposed Hatoum to cutting-edge practices that transcended national boundaries—an internationalist perspective that would later inform her nuanced position between the identity-based focus of the British Black Arts movement and the formalist concerns of British contemporary art.

Her social circle included creatives from various disciplines—art, design, fashion, and photography—including the aspiring art dealer Edward Totah (1949–95) and painter Fadi Barrage (1939–1988). The city’s cultural dynamism was further enhanced by numerous international cultural centres and the annual Baalbek Festival, which attracted global artists, musicians, and performers.13 Her immersion in Beirut’s diverse creative community established a first pattern of cross-cultural dialogue that helps to understand her navigation in London’s art world and others.

The year before Faris pressed the button, Hatoum had graduated from the Beirut College for Women (BCW)14 with an Associate of Applied Science degree in graphic design.15 This path represented a compromise with her father, who refused to support her through a four-year art programme, insisting instead on a more “practical” education. Though focused on graphic design, Hatoum seized every opportunity to pursue her true passion, enrolling in art classes whenever possible. As she recounted in interview, she particularly cherished a “Drawing from the Human Figure” class taught by Samia Ouseiran Junblatt (1944–2024) and developed an early interest in photography.

After graduation, Hatoum worked at Young & Rubicam, a major American advertising agency in Beirut. Despite the company’s prestige, she found the eighteen months there deeply unfulfilling. While she gained valuable technical skills in printing, photography, and filmmaking—which later enabled her to take on better-paying freelance work—she grew increasingly troubled by the ethics of advertising. To nurture her creative spirit during this period, she enrolled in evening classes, including drawing with Hassan Jouni (b. 1942) and ceramics courses with Dorothy Salhab Kazemi (1942–90) at what had become Beirut University College (BUC). Kazemi became a significant mentor, encouraging Hatoum to pursue further art education abroad.

In June 1975, what was intended as a brief visit to London became an indefinite stay when the Lebanese Civil War intensified. With Beirut’s airport closed for nine consecutive months, Hatoum remained in Britain, eventually establishing herself there permanently. The initial two-year war (1975–77) was followed by a series of related conflicts between shifting alliances of Lebanese groups and external actors, who destabilized Lebanon until 1990 and beyond. With the turmoil in Lebanon, Kazemi’s suggestion would materialize sooner than expected. Moreover, this abrupt and forced departure from Beirut would mark a significant turning point in Hatoum’s life and artistic trajectory, transforming her relationship with place, belonging, exile, and creative expression—themes that would become central to her internationally acclaimed body of work.

Unlike artists born in Commonwealth countries who formed the core of the British Black Arts movement, Hatoum’s experience of double displacement—through her Palestinian heritage and then her prohibited return to Lebanon—gave her approach a distinctive complexity in addressing questions of belonging. This complexity would both align her with and distinguish her from Araeen’s theoretical frameworks, which primarily addressed postcolonial identity within the British imperial context at large rather than the intricately layered displacements characteristic of the Israeli colonization and the Lebanese Civil War experience beyond the British imperial realm. Hatoum’s formative Beirut years thus provided not just biographical background but the essential conceptual foundation for her later artistic interventions in the UK—establishing a transnational perspective that would both contribute to and complicate the discourses of the British Black Arts movement.

Hatoum’s arrival in London in 1975 on what was meant to be a short visit—soon permanent due to the Lebanese Civil War—positioned her uniquely within Britain’s artistic landscape at a pivotal moment when identity politics were beginning to reshape British art discourse through what Hall called “the black experience,”16 which emerged as a hegemonic identity framework that critiqued the positioning of non-white communities as the invisible “other” within predominantly white British aesthetic and cultural discourses. By then, Hatoum had already left her position at Young & Rubicam, having made the decision to return to BUC to pursue a BA degree in Fine Art. She had registered for her first term, confident that her acquired freelance design skills would sustain her financially during her studies. Her long-term vision included applying for postgraduate studies in London afterward, and her 1975 visit to the British capital was partly to explore suitable programmes. When violence escalated in Lebanon, she adapted quickly—viewing this unexpected turn as an opportunity to accelerate her artistic education. Having missed application deadlines for government-funded art schools, she enrolled in a foundation course at the private Byam Shaw School of Art,17 an institution whose traditional approach would both inform and ultimately provoke her movement toward the politically engaged art practices that would later align with aspects of the British Black Arts movement.

The traumatic circumstances of Hatoum’s early London years critically shaped her artistic development in ways that would later distinguish her work within British political art circles. Living in “a cold and harsh environment” while carrying the emotional weight of war in Lebanon—she was “too concerned about the war and felt a constant fear of losing [her] parents who lived very close to the green line where most of the fighting took place”—Hatoum experienced what Edward Said would later term “the unhealable rift forced between a human being and a native place.”18 This existential condition of exile provided her with a lived experience of marginality that would position her work at a critical intersection with British black artists’ concerns, even as her specific experience differentiated her from British-born artists of colour and those from former colonies.

Hatoum’s encounters with traditional art education at Byam Shaw (1975–79) became instrumental in her eventual rejection of western artistic conventions. The school’s insistence on traditional forms and dismissal of photography (“I buried my Nikon camera in a bank vault for a long time”) represented precisely the Eurocentric artistic hierarchy that Rasheed Araeen and other black artists and theorists would critique. Despite this traditionalism, the foundation year introduced her to diverse methods and materials, differing significantly from the American-style education she had experienced in Beirut. She particularly valued the British tutorial system, which provided dedicated studio space and one-on-one guidance from instructors whenever needed. Her initial compliance with these traditions—progressing from life drawing to abstract expressionism’s “strange cathartic effect”—became almost ritualistic: painting through the night until physical exhaustion overtook her, surrendering completely to the creative act in a profound emotional and intellectual journey. Followed by her intellectual rebellion against them, it paralleled the broader movement in British art toward questioning canonical western, racist, and misogynistic art representations from non-western perspectives.

This broader questioning of artistic traditions influenced the artist’s engagement with kinetic and performative practices, which can be traced to a pivotal encounter in 1977, when David Medalla (1942–2020) visited the Byam Shaw to deliver a lecture on his work alongside that of several Brazilian and South American artists, including Hélio Oiticica (1937–80), Lygia Clark (1920–88), and Tunga (1952–2016). This presentation proved formative, introducing concepts that would influence Hatoum’s artistic approach. At the time, she was experiencing dissatisfaction with the static nature of painting and had begun experimenting with a large-scale work that documented the daily transformations occurring within her studio environment. Medalla’s observation that her painting appeared dynamic, with nothing seemingly fixed within its composition, affirmed her intuitive move towards more fluid artistic expressions.

Another turning point came with her discovery of Marcel Duchamp’s work and Lucy Lippard’s Six Years: The Dematerialisation of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972,19 which became her “bible.” This intellectual encounter catalysed a decisive reorientation toward conceptual practice, as she began “making 3D objects, using industrial materials and playing with what [she] called invisible forces like light, electricity and magnetism.” This shift represented not merely a stylistic evolution but a political one—anticipating the formal strategies through which she would later engage with issues of displacement, power, and exile while maintaining her distinctive artistic vocabulary.

Hatoum’s transition to the Slade School of Art (1979–81) marked her entry into circles more directly engaged with critical theory and postmodern thought.20 At this prestigious institution, her artistic development benefited from encounters with key mentors whose influence transcended technical instruction to shape her political consciousness. Mary Kelly’s (b. 1941) visit during Hatoum’s first year proved transformative, as Kelly “turned [her] on to feminist theories, especially the discussions around the gaze and the representation of the female body.” These feminist perspectives provided Hatoum with critical tools to analyse power relations embedded in visual representation—theoretical concerns that paralleled the British Black Arts movement’s critique of racial representation while adding a gendered dimension often underdeveloped in Araeen’s frameworks.

Stuart Brisley’s (b. 1933) “antiestablishment attitude” further radicalized Hatoum’s approach, offering a model of institutional critique that complemented her growing political awareness. Through these mentorships and her engagement with performance-oriented student peers, Hatoum developed an artistic practice increasingly centred on “women’s and minority rights through artistic, social, and political discourse”—a focus that positioned her work in productive dialogue with surveillance and Michel Foucault and Jeremy Bentham’s idea of ever-visible inmates, echoing the British Black Arts movement’s concerns while maintaining her distinctive perspective as an artist from the Mashreq navigating complex displacements.

Hatoum’s educational journey thus represents a crucial evolution that positioned her at the intersection of multiple artistic and political currents in 1980s Britain. Her progression from traditional training to conceptual and performative practice, informed by feminist theory and institutional critique, equipped her with a sophisticated artistic language through which to address issues of power and belonging while maintaining a perspective shaped by her specific transnational journey. This particular trajectory established the foundation for her later engagement with Araeen’s theoretical framework, as her work increasingly negotiated the politics of identity—which Hatoum considered not as something fixed but as forever changing, rendering pointless any attempt to engage with rigid definitions of identity, as these inevitably lead to clichés and stereotypes from which she sought to distance herself21—and representation from her unique position of double displacement.

Art critic Guy Brett (1942–2021), in a comprehensive monograph on Hatoum’s work, identified three distinct phases in her artistic evolution.22 The first—brief but formative—encompassed her “free experimentation” during her art education in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Between 1982 and 1988, Hatoum transitioned into what Brett termed her “issue-based” period, expressed through performances and videos exploring themes of violence, gender, alienation and exile.23 Brett marks the third phase from the creation of The Light at the End (1989), an installation signalling Hatoum’s return to the minimalist language she had explored during her education, which became infused with subtle political connotations. This final phase led to her now-renowned installations and sculptural objects.

These artistic phases unfolded against the backdrop of significant upheaval in British art during the late 1970s and early 1980s—a period defined by feminist movements, postcolonial critiques, and growing awareness of institutional power structures. As a British-Palestinian artist navigating a predominantly white, upper-middle-class British art environment, Hatoum developed a uniquely powerful, intersectional artistic voice. Her early 1980s performances investigated the complex relationships between body, technology, and audience perception through visual illusions and multisensory experiences.

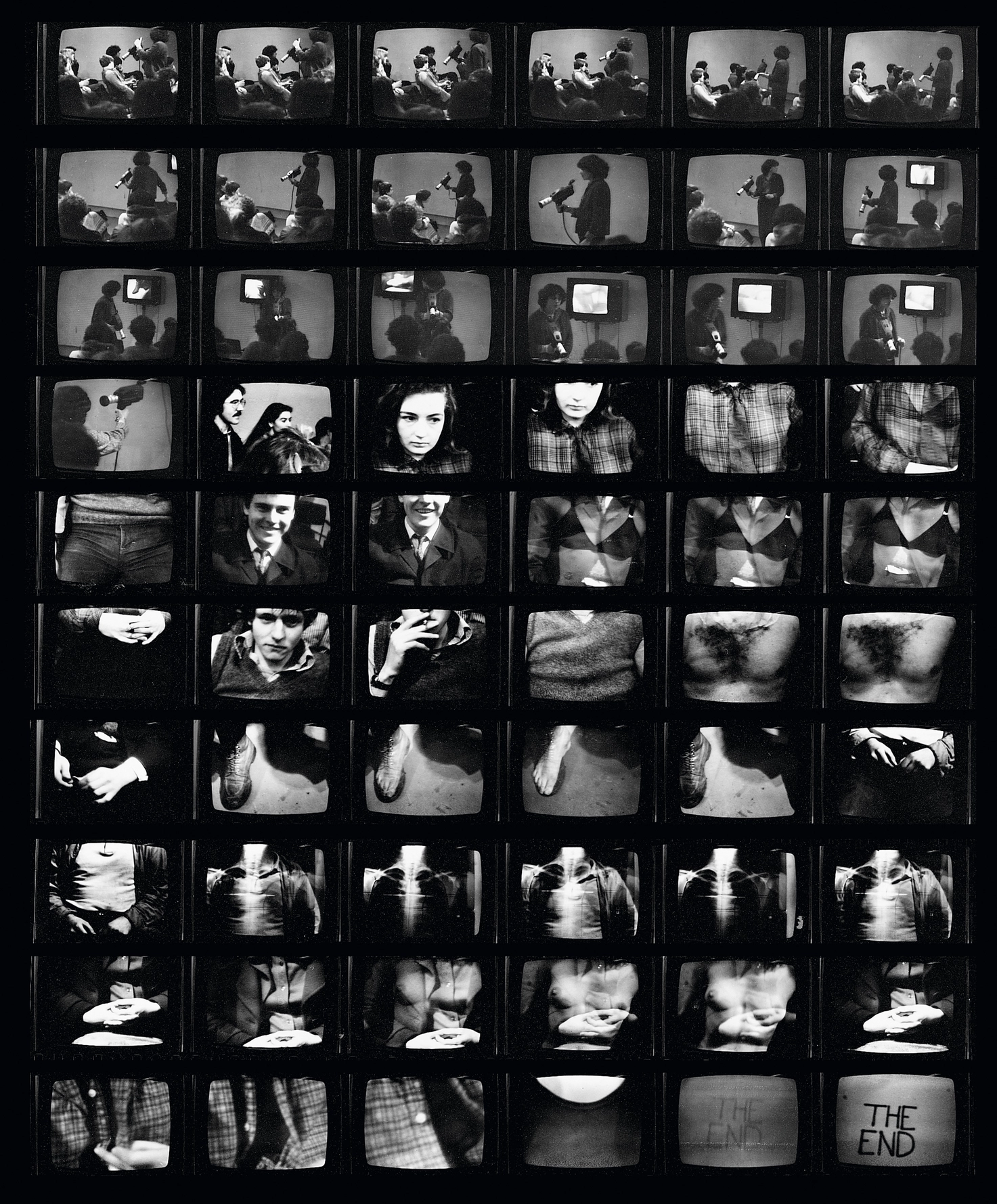

Artworks like Don’t Smile, You’re on Camera! (1980) (fig. 3) revealed her early intellectual engagement with Foucault and Bataille, alongside feminist reinterpretations of Freudian “master narratives,” as she explored surveillance, bodily representation, and technological manipulation. In this piece, Hatoum deployed a live video camera as a provocative instrument of scrutiny. By slowly panning across the audience and focusing on intimate body parts—faces, torsos, crotches—she challenged traditional boundaries of personal space and visibility. The performance was technically sophisticated: shirts seemingly faded to reveal ghostly images of bare skin, jackets turned transparent, and bodies appeared overlaid with X-ray-like representations. This complex visual experience, created with three unseen assistants using multiple camera feeds, questioned fundamental notions of privacy, consent, and the gaze.

Hatoum’s early performances were guided by a purist vision of live art as inherently ephemeral—existing only in the moment of enactment. For her, the audience’s experience and memory—inevitably distorted over time—constituted an integral element of the work itself. Practical constraints reinforced this approach; lacking resources to organize her own documentation, the few existing records of these performances were facilitated by hosting venues, emphasizing the intangible nature of her early practice.

A year after graduating from the Slade, Hatoum participated in the Women Live festival at London’s Film-Maker’s Co-op in May 1982. In a performance lasting seven hours, she covered her naked body in clay and confined herself within a small transparent polythene structure, repeatedly struggling to stand, slipping and falling. This action was accompanied by a cacophony of sounds—revolutionary chants and news bulletins in Arabic, English, and French—and a distributed leaflet stating:

As a Palestinian woman this work was my first attempt at making a statement about a persistent struggle to survive in a continuous state of siege. […] As a person from the ‘Third World’, living in the West, existing on the margin of European society and alienated from my own […] this action represented an act of separation […] stepping out of an acquired frame of reference and into a space which acted as a point of reconnection and reconciliation with my own background and the bloody history of my own people.24

Presented on 30 May 1982, Under Siege was performed a week before the Israeli invasion of Lebanon, on 6 June 1982, that led to the siege of Beirut. In fact at the time, she thought that her performance was a premonition for what happened a week later. It also marked her first performance explicitly denouncing the Israeli government’s violence, the issue of otherness in the UK, and expressing her Palestinian identity to a British audience. The work received serious critical engagement, with some commentators drawing parallels to the Irish prisoners’ hunger strikes of the previous year.25 It proved controversial both for its medium—rejecting the traditional art object in favour of concept—and for its approach to body, gender, and political identity.

Under Siege was performed again at Aspex Gallery in Portsmouth, on 2 October 1982, and lasted three hours (fig. 4). The media response revealed more about societal prejudices than the performance itself. Hatoum later reflected: “All the fuss that was made about this performance came out before it even took place at the gallery in Portsmouth. It was all based on a false assumption that the performance contained nudity.” The sensationalist headline in The Sun—“Naked in Red Slime”—triggered a national controversy, transforming her serious artistic statement into tabloid scandal. Forced to defend her artistic integrity, she held a press conference to articulate her intentions. Ironically, despite numerous photographers present at the performance, no substantive reporting emerged—the clay-covered structure so completely obscured her form that the sensationalist premise collapsed. This media reaction exposed the complex landscape of performance art in early 1980s Britain, where the press seemed more comfortable sensationalizing the work than engaging with its profound political commentary on Palestinian and Lebanese resistance under Israeli oppression.26

It also aligns with the broader approach of Black Arts in interrogating the white gaze, where artists like Adrian Piper (b. 1948) similarly questioned dominant institutional structures, and as Amina Kayani emphasizes, both Piper and Hatoum’s work “directly interrogates the complicity of white audiences in the imperialist structures” they denounce.27 Furthermore, this performance exemplifies the shift Brett identified as Hatoum’s second phase of work. What he termed “issue-based” work, she herself called “time-based work” of the 1980s—art operating through metaphors that positioned the body as a representation of broader society.

Although Hatoum had presented several solo performances, including Don’t Smile, You’re on Camera! at the Battersea Arts Centre in 1980 (fig. 3) and at the Institute of Contemporary Arts’ New Contemporaries in 1981, followed by the 1982 performance Under Siege mentioned above (fig. 4), the mid-1980s trajectory of Hatoum’s practice was significantly shaped by international opportunities beyond the constraints of the British art scene. In 1983, a pivotal invitation from the artist-run centre Western Front in Vancouver marked a transformative moment in her career. Western Front not only facilitated her first Canadian performance tour but inaugurated a series of annual international engagements that expanded her artistic horizons, resulting in works such as So Much I Want to Say (1983), The Negotiating Table (1983), Changing Parts (1984), and Variation on Discord and Divisions (1984). These international networks proved crucial for her.28 By 1984, her performance and video work had begun circulating through significant alternative spaces, including New York’s Franklin Furnace.

The year 1984 proved central for Hatoum beyond her transatlantic endeavours. The initial connection with Medalla at the Byam Shaw in 1977 led to a significant opportunity in 1984, when he was serving as curator of the Second International Festival of Performance at South Hill Park Arts Centre in Bracknell and invited Hatoum to perform Them and Us … and Other Divisions (1984) (fig. 5). It was at this festival that she encountered both Rasheed Araeen and Guy Brett: “Meeting those three individuals [Medalla, Araeen, and Brett] was not only a very significant moment for me but it connected me for the first time with like-minded people who became my support system and like family to me.” By this period, she had already begun creating installations that explored what she termed “invisible forces”—magnetism, light, and electricity—while incorporating kinetic elements into her sculptural practice, exemplified by works such as Self Erasing Drawing (1979), which subsequently evolved into the large-scale installation + and – (1994). Brett, whose book on kinetic art aligned with her artistic investigations,29 demonstrated keen interest in her performative work, attending several of her Brixton performances the following year and subsequently reviewing them. Their professional relationship developed into a lasting friendship that endured until Brett’s death in 2021, with his continued support proving invaluable to her artistic career.

While these four did not collaborate formally altogether, their encounters fostered a shared artistic sensibility that emphasized independent thought and personal subjectivity, transcending both national narratives—Britishness—and overarching discourses on postcolonialism or “black artist” and “Third World arts.” This constellation presented expanded possibilities for negotiating “transnationalism” as both perspective and artistic method in Britain between the 1960s and 1980s. Known for their stance against the endemic racism and discrimination in British art institutions, this constellation provided Hatoum with like-minded individuals who made her feel less isolated. It was at this juncture that she found in Araeen’s conceptual framework a verbal language to define the issues she had been grappling with concerning the notions of “Third World arts” and the “black artist.”

Rasheed Araeen’s definitions of these concepts were intrinsically connected to the political and social dimensions of the category “Black British”—a category with significance beyond the art world.30 This classification emerged partly from massive labour organizing efforts in the 1980s protecting immigrant workers recruited from South Asia and the Caribbean to rebuild British manufacturing, who upon arrival faced treatment as second-class citizens.31 Because this “Black British” category actively drove political demands, it resonated powerfully within the art world as well, representing “other artists” organizing against colonial power structures.

During the 1980s, class struggle and worker organization in Britain provided critical historical context for artists of colour, establishing frameworks for racial confrontation that transcended purely aesthetic concerns. The concept of a “third place”—neither fully integrated into the mainstream art world nor limited to ethnic community art—emerged as a vital alternative space where artists like Hatoum could develop work that challenged colonial power structures while engaging with western artistic traditions.

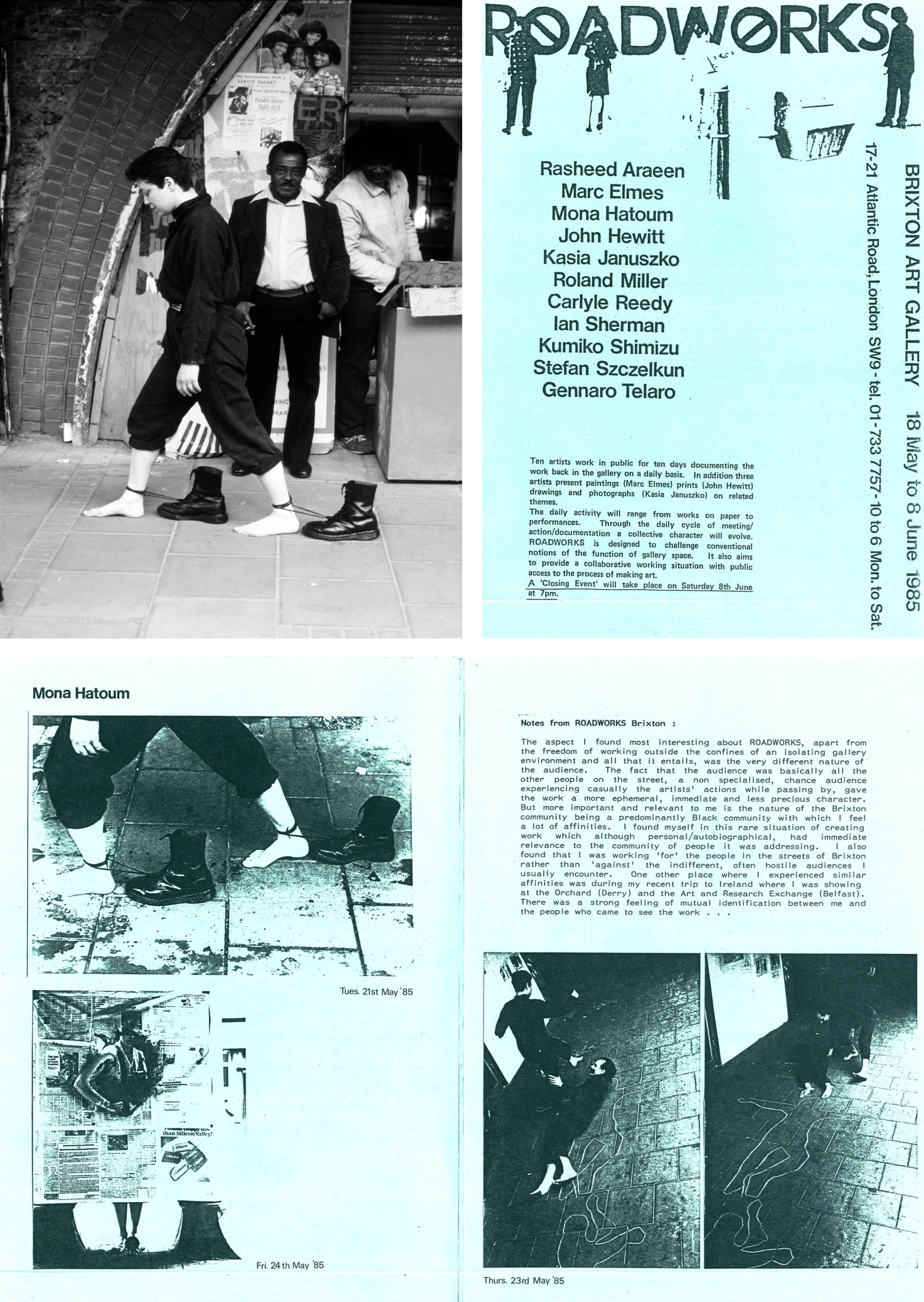

While neither Hatoum nor Araeen were directly involved in grass-roots political movements or resided in Brixton—an area where youth of colour had risen against systemic police brutality—their artistic practices were deeply informed by political consciousness. Araeen had been active in the Black Panther Movement since the 1970s, a connection that significantly shaped his approach to art and cultural activism. This political engagement manifested in his work with the Brixton community,32 particularly through the Brixton Art Gallery (BAG),33 where both he and Hatoum collaborated with the collective between 1984 and 1986. These connections represented more than professional associations; they were strategic alliances in creating counter-institutional spaces where marginalized artists could present work outside the white-dominated mainstream.

On 23 March 1984, the Brixton Artists Collective (BAC) invited Hatoum to participate in the Multiples exhibition—a showcase specifically designed for serially produced works including photographs, prints, videos, and posters. Her contribution, “Under Siege” Summer 1982. (Series One), comprised photographic documentation of her earlier performance at the London Film-Makers Co-op (fig. 3).34 This marked her first engagement with art spaces explicitly organized around racial politics. Araeen was similarly invited to participate in the second open exhibition organized by Creation for Liberation (CfL)35 from 17 July to 8 August 1984, where he presented How Could One Paint a Self-Portrait? (1978–79),36 a work directly addressing the complexities of identity in a postcolonial context.

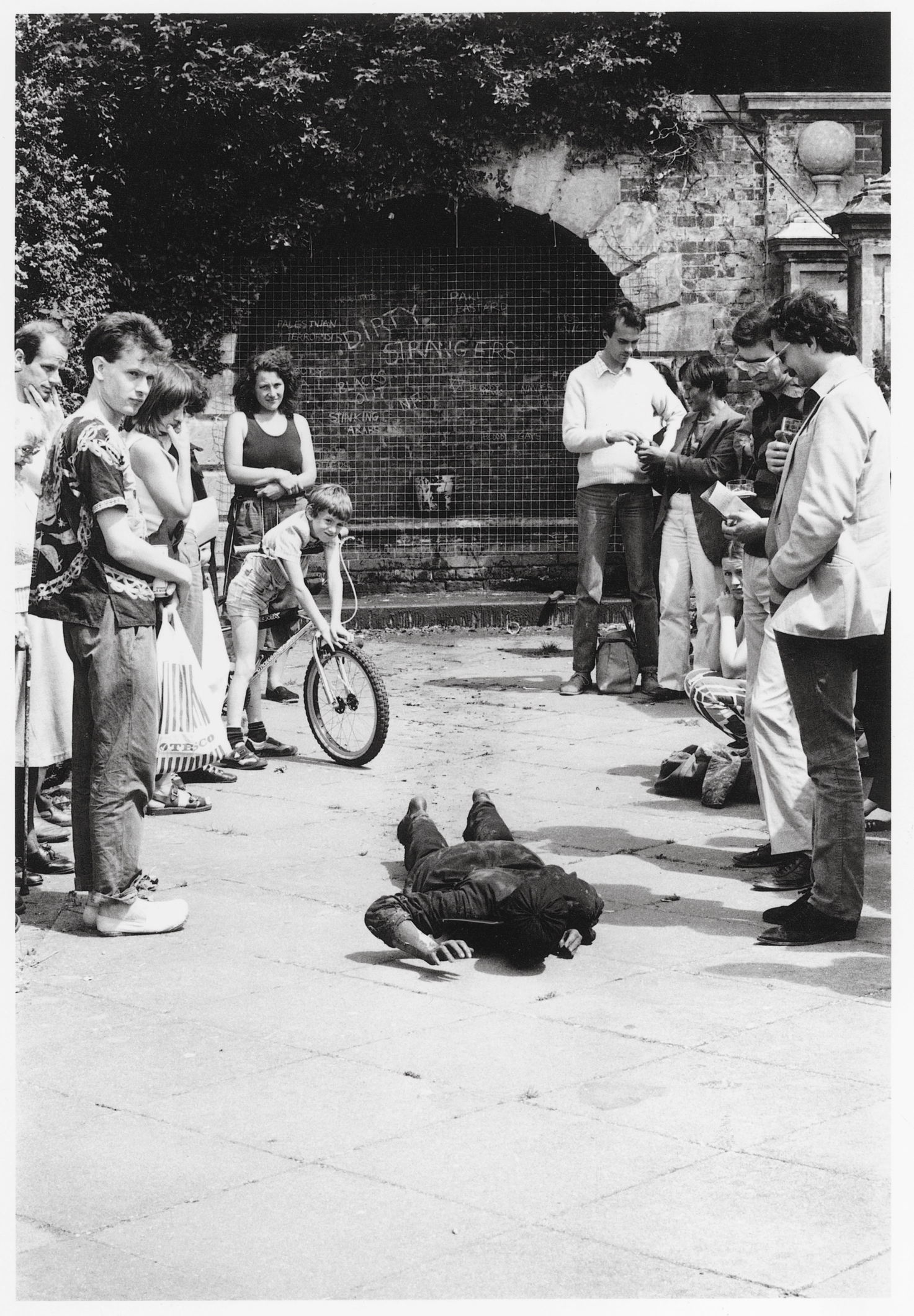

The following year, both artists deepened their engagement with marginalized communities through participation in Roadworks (18 May–8 June 1985). This initiative, organized by artist Stefan Szczelkun (b. 1952), deliberately positioned artistic interventions outside conventional gallery contexts, bringing them directly to Brixton’s predominantly black working-class neighbourhood.37 In one documented performance, Hatoum walked barefoot through Brixton’s streets with heavy Dr. Martens boots—footwear symbolically associated with police authority and skinhead subculture—tethered to her ankles (fig. 6, top left). This created a powerful visual metaphor juxtaposing vulnerability with oppressive power, making visible the everyday violence experienced by racialized communities. In a companion performance with Szczelkun, both artists appeared barefoot, dressed in black with mouths sealed by tape, enacting a sequence wherein they alternately outlined each other’s prone bodies with white markings reminiscent of crime scene demarcations—a powerful commentary on the criminalization of black bodies in British society (fig. 6, bottom right).

A pivotal moment in this developing “third space” came in March 1986, when funding cuts from the Greater London Council (GLC) forced the cancellation of the proposed Essential Black Art exhibition. In response, Araeen quickly organized an alternative exhibition titled Third World Within at BAG (fig. 7), where Hatoum hung the artworks, as Araeen was away at his father’s funeral.38 Running from 31 March to 22 April 1986, this exhibition showcased works by Afro-Asian artists in the UK, including Hatoum’s video So Much I Want to Say (1983)—a work that powerfully expressed the silencing of marginalized voices through a series of images showing a woman’s face with male hands covering her mouth. The exhibition aligned with the objectives of Black Umbrella, an organization Araeen established in 1984 to document the overlooked contributions of black/Afro-Asian contemporary artists to British culture. This initiative represented more than mere documentation; it was an act of historical intervention against systematic erasure and division.

In his accompanying press release for Third World Within, Araeen offered a critical redefinition of “Black Art” that would prove influential. He argued that it was not merely art produced by black people, but rather a specific contemporary art practice emerging directly from the struggle against racism and explicitly addressing the human condition of black people in western society.39 This definition provided a theoretical framework that transcended essentialist notions of identity, focusing instead on political positioning and critical engagement.

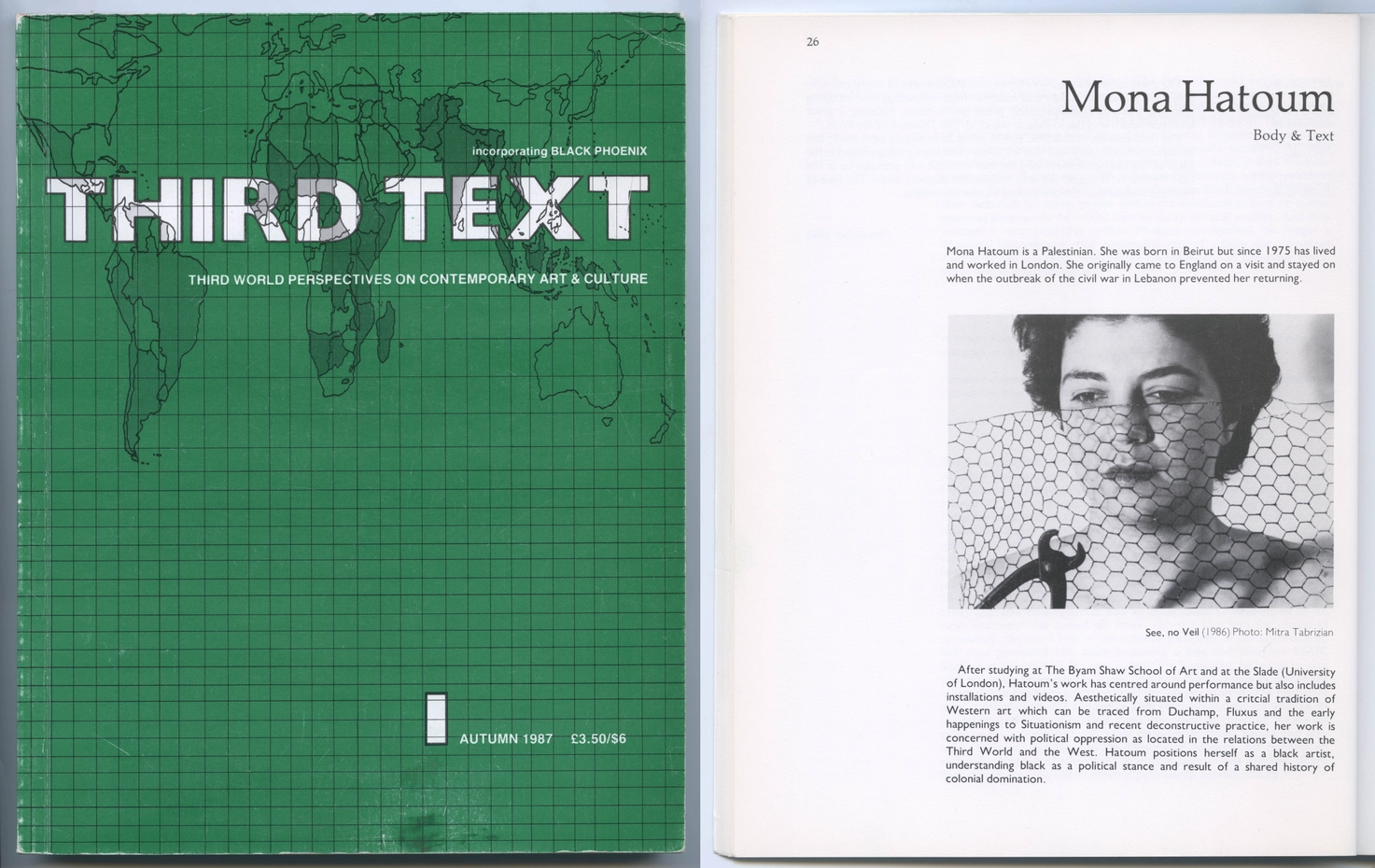

It was within this intellectual and political framework that Hatoum situated herself in the latter half of the 1980s. Her involvement extended beyond exhibition participation to active theoretical engagement through Araeen’s journal Third Text, which sought to create a “third space” of critical discourse outside mainstream art publications. Her membership—alongside David A. Bailey, Guy Brett, Mahmood Jamal, Gavin Jantjes, Sarat Maharaj, and Partha Mitter—on the editorial advisory committee positioned her inside a platform developing postcolonial art theory. In the journal’s landmark first issue in 1987, Hatoum contributed the article “Body & Text,” articulating her artistic approach in conversation with Araeen’s critical thinking (fig. 8).40 This theoretical contribution demonstrated how her practice was not merely responding to identity-based expectations but actively reshaping the discourse around art and politics.

Hatoum’s artistic strategy during this period was sophisticated and multi-layered. She positioned her work within the lineage of western avant-garde movements—citing influences from “Duchamp, Fluxus and the early happenings to Situationism and recent deconstructive practice”41 (fig. 8)—while simultaneously reframing these traditions through the lens of postcolonial critique. Rather than simply adapting western artistic languages, she transformed them by centring the political dynamics of oppression, particularly the complex power relations between the Global South and the west. This approach represented not mimicry but radical reinterpretation and critique. By simultaneously engaging with western artistic traditions while identifying as a black artist as defined by Araeen, Hatoum occupied a unique position that allowed her to challenge established hierarchies from both within and outside dominant structures. This dual positioning enabled her to critically redefine British modern and contemporary art in a postcolonial context while also contributing to political and feminist art discourses.

Araeen’s own experience illuminated the necessity of this strategic positioning. Prior to advocating for an emancipatory arts movement across the Third World, he had been denied recognition as a minimalist sculptor and excluded from the British artistic sphere due to his non-western origins.42 This exclusion led to his work being interpreted solely through the lens of his cultural background rather than in conversation with the western minimalist tradition it clearly engaged with.43 Hatoum’s alignment with Araeen’s critical framework helped her navigate similar potential pitfalls in the predominantly white British art world of the 1980s.

Her conscious adoption of the term “black artist” functioned not as a limiting label but as a political stance challenging racial hierarchies in art institutions. This identification served multiple strategic purposes: it provided a protective framework against potential marginalization while simultaneously creating space for a critique of systemic racism in the contemporary art world. By rejecting narrow definitions based on national or ethnic origins while embracing political solidarity, Hatoum positioned herself within a broader, more nuanced artistic discourse that effectively dismantled restrictive categorizations of “ethnic art” and “primitivism.”

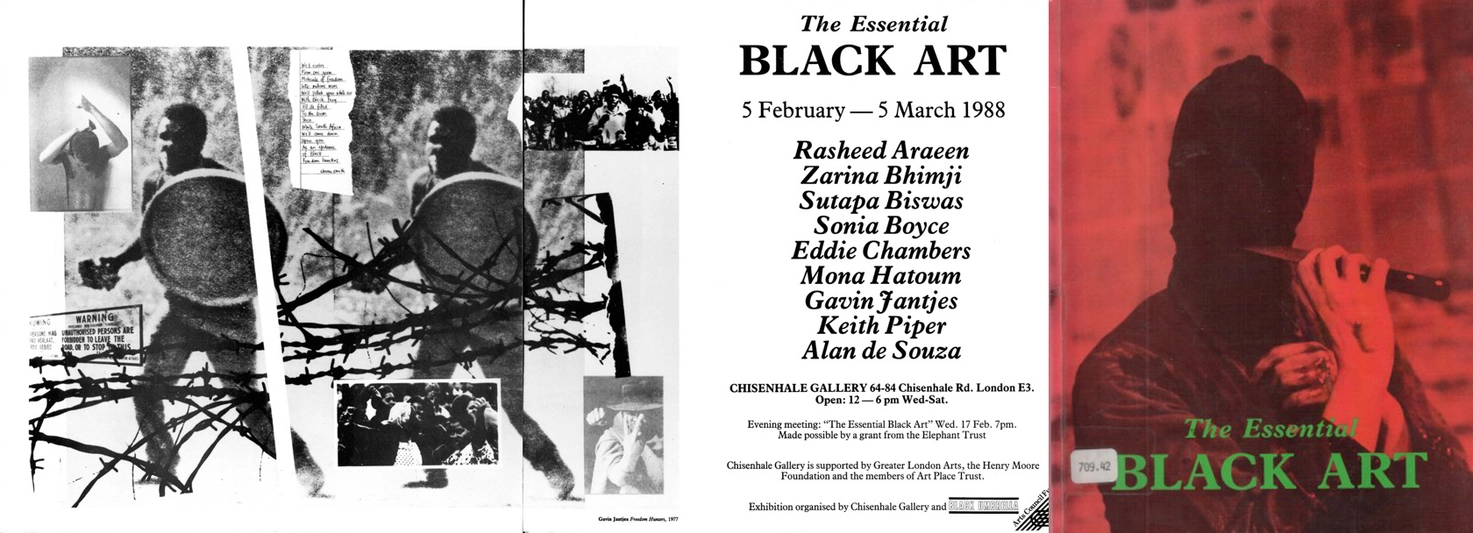

Through these strategic associations, Hatoum participated in two additional landmark exhibitions curated by Araeen. The Essential Black Art, running from 5 February to 5 March 1988, at the Chisenhale Gallery, showcased her work alongside other significant artists including Piper, Biswas, and Himid. The exhibition’s catalogue featured Hatoum’s 1984 performance Variation on Discord and Divisions on its cover—a work that powerfully addressed fragmentation, conflict, and the politics of representation (fig. 9).44 This visual prominence underscored her growing significance within black artists.

The Essential Black Art served as precursor to Araeen’s most ambitious curatorial project, The Other Story: Afro-Asian Artists in Post-War Britain, presented at the Hayward Gallery from 29 November 1989 to 4 February 1990, where Hatoum presented three videos—So Much I Want to Say (1983), Changing Parts (1984), and Measures of Distance (1988)—and Over My Dead Body (1988), a metro billboard project hung outside the Hayward Gallery (fig. 10).45 As the first comprehensive retrospective of British African, Caribbean, and Asian modernism in a major institution, the exhibition represented a significant intervention in British art history. However, its polarized critical reception—simultaneously attracting both derision and acclaim—revealed the deep-seated resistance to integrating these artists into mainstream historical narratives.46

Despite its groundbreaking nature, The Other Story did not immediately transform institutional practices. Only in recent decades have scholars begun systematically interrogating the meaning of “black” as a political category and engaging meaningfully with the historical stakes involved. This newer scholarship has illuminated important ideological divisions within British Black Arts movements: between Black Power art (with its explicit political agenda serving black communities), Third World solidarity models advocating cross-communal organization against colonial structures and broader cultural affirmative approaches embracing all artistic production by black creators without imposing political requirements.47

A revealing aspect of this complex landscape emerges when examining how certain exhibition spaces were treated in artists’ professional narratives. According to Szczelkun, both Hatoum and Araeen notably omitted the BAG from their official curricula vitae despite their significant involvement with the gallery.48 This interpretation appears questionable, as Hatoum has explained that the BAG was consistently included in her extensive CVs, and omissions in certain catalogues were due to space constraints and editorial decisions to focus on her installation work from 1989 onwards.49 However, Araeen’s landmark The Other Story exhibition made no mention of his earlier Third World Within show.50 Beyond the facts, this episode illuminates the precarious position of alternative exhibition spaces within art world hierarchies. Without conventional selection committees—where artists instead self-nominated for exhibitions—these venues apparently carried less professional capital despite their cultural significance. These dynamics reveal how deeply entrenched notions of institutional validation can render important platforms for diverse artistic voices effectively invisible in official histories.

Hatoum’s own reflection on these dynamics, articulated in her 1987 statement, offers crucial insight into her strategic navigations:

There is also the issue of community arts. There is a lot of pressure on Black artists to work within their own community. We are being told, “The most useful contribution you can make is to work with your own ‘ethnic’ art within your own ‘ethnic’ community.” In other words, “Leave the mainstream art space for the ‘more important’ Western white male figures to project their fantasies in.” It seems to me that this is a deliberate attempt to keep Black people in their place. What I’m hearing then is marginalization, and there is an implicit racism in this attitude. The implication is that we do not have full creative potential and we are not capable of participating in art activity at all levels. I am not saying that there is something wrong with community arts, but it will never be my main area of activity. I would like to use every platform available to me to fight for access to those spaces that are denied me.51

This statement crystallizes Hatoum’s refusal to be confined to prescribed artistic territories. Her insistence on accessing all platforms—from community spaces to mainstream institutions—reflects a sophisticated understanding of power within the art world. Rather than accepting a binary choice between assimilation and separation, Hatoum carved out a third position that maintained critical distance while engaging with dominant institutions. This approach would prove foundational to her subsequent artistic development as she transitioned toward installation work in the late 1980s and early 1990s, eventually achieving international recognition while maintaining her political commitments.

Hatoum’s navigation of these complex terrains during this formative period demonstrates how the creation of “third spaces”—whether through alternative galleries, critical journals, or strategic identifications—provided crucial platforms for artistic development outside restrictive categories. Her experience illuminates not just personal artistic evolution but broader structures of exclusion and resistance that continue to shape contemporary art discourse. By understanding these historical dynamics, we gain deeper insight into how artists from marginalized positions have actively shaped artistic traditions rather than merely responding to them—creating alternative spaces that transform the very meaning of contemporary art.

Through the employment of a monographic approach, this article has traced the multifaceted complexity of Hatoum’s artistic evolution throughout the 1980s. This detailed portrait constitutes a critical microhistory that challenges established narratives, revealing precisely how her formative experiences shaped the conceptual foundations of her subsequent international practice.

Hatoum’s artistic development emerges as far more complex than conventional narratives suggest. Her formative period in Beirut’s experimental artistic milieu—particularly through her interactions with spaces like Contact Gallery—provided crucial conceptual, international, and political groundwork that predated her London training. Similarly, her engagements in Canada from 1983 onwards represented transformative opportunities that allowed her to develop her distinctive voice within new institutional frameworks. By recognizing these multiple, interconnected centres of influence, we can challenge Eurocentric art historical frameworks that position London as the exclusive catalyst for her artistic maturation, instead revealing a transnational trajectory where her practice evolved through dialogue across diverse geographic and cultural contexts.

Revisiting Hatoum’s participation in Third Text, the BAG, and Araeen’s exhibitions illuminates not only Brixton’s significance as a nexus for politically engaged art practice but also chronicles the early collaborations between Hatoum and Araeen that would prove influential. This historical contextualization reveals how terms such as “Third World,” “British Black Arts,” and “Black British” underwent continuous redefinition during this decade, reflecting the fluidity of cultural identities within Britain’s postcolonial artistic landscape. Notably, Hatoum’s critical positioning as a “black artist” in these contexts has been systematically marginalized within art historical narratives—a neglect evident even within British black artists’ discourses and in her subsequent artistic statements.

Hatoum’s engagement transcended mere affiliation with the British Black Arts movement. She strategically positioned herself within a precisely delineated symbolic space—a networked constellation of intellectual and artistic solidarity. Through nuanced associations with figures like Araeen, she navigated the complex terrain of institutional critique not by subscribing to a monolithic collective identity, but by cultivating a sophisticated, interconnected discourse of resistance and artistic autonomy. This distinctive positioning explains her placement among the “Other Artists” in Himid’s conceptual mapping of the movement (fig. 1).

The trajectory of Hatoum’s career underwent a decisive transformation in 1989 when she secured a position as senior fellow in fine art at the Cardiff Institute of Higher Education. This institutional appointment marked what she characterized as “a full stop” in her performance practice, catalysing a return to object-making that would propel her from the margins of British art into its mainstream.52 The security of a regular salary and access to a dedicated studio space for the first time liberated her from the financial precarity that had constrained her earlier work. This shift coincided with a growing disillusionment with performance art, prompting her to reconnect with the conceptual frameworks and minimalist language that had initially shaped her practice. This strategic reorientation proved remarkably effective in establishing her institutional recognition: her first solo museum exhibition at the Pompidou Centre followed in 1994, a Turner Prize nomination in 1995, and her inaugural show at Tate Britain in 2000. This rapid ascent from marginal performance artist to internationally acclaimed contemporary one demonstrates how Hatoum’s nuanced navigation of artistic and institutional contexts ultimately enabled her to achieve the visibility and influence that had remained elusive during her more explicitly political performance period. While maintaining personal connections to Lebanon, her artistic engagement with the region’s contemporary scene only materialized around the late 1990s and early 2000s, when she began to connect with local artists like Akram Zaatari (b. 1966) and Walid Raad (b. 1967) when they participated in the Ayloul Festival in Beirut in 2000.

The 1980s, while characterized by resistance to far-right policies, also saw a problematic tendency to fetishize works associated with the British Black Arts movement, often reducing them to mere documents of the era53 or simplistic expressions of non-white identity.54 Hatoum’s practice fundamentally resists such reductive categorization by refusing confinement to singular narratives, categories, or geographies. This nuanced understanding not only enriches our appreciation of her artistic development but also broadens our conception of how artistic movements and identities formed across borders during this pivotal period, inviting a more complex framework for understanding transnational artistic trajectories within postcolonial contexts.

First and foremost, I wish to express my profound gratitude to Mona Hatoum for her generous availability and meticulous attention to detail, without which this article would not have come to fruition. I am equally indebted to Sam Bardaouil for facilitating the initial contact with the artist, and to Nadia von Maltzahn for her gracious support, consummate professionalism, and exemplary editorial guidance throughout the development of this volume of Manazir Journal. I must also extend my sincere appreciation to the peer reviewers, whose excellent work and insightful feedback were instrumental in elevating this article to its current form; without their rigorous assessment and valuable suggestions, this work would not have reached its present standard.

Araeen, Rasheed. The Essential Black Art. London: Chisenhale Gallery and Black Umbrella, 1988. Catalogue of an exhibition held at the Chisenhale Gallery, London, 5 February–5 March 1988.

Araeen, Rasheed. “From Primitivism to Ethnic Art.” Third Text 1, no. 1 (Autumn 1987): 6–25.

Araeen, Rasheed. “How I Discovered My Oriental Soul in the Wilderness of the West.” Third Text 6, no. 18 (Spring 1992): 85–102.

Araeen, Rasheed. Making Myself Visible. London: Kala, 1984.

Araeen, Rasheed. “A New Beginning: Beyond Postcolonial Cultural Theory and Identity Politics.” Third Text 14, no. 50 (Spring 2000): 3–20.

Araeen, Rasheed. “The Other Immigrant: The Experiences and Achievements of Afro Asian Artists in the Metropolis.” Third Text 5, no. 15 (Summer 1991): 17–28.

Araeen, Rasheed. “Preliminary Notes for a Black Manifesto.” Black Phoenix 1 (Winter 1978): 3–12. Reproduced in Black Phoenix: Third World Perspective on Contemporary Art and Culture, edited by Rasheed Araeen and Mahmood Jamal. New York: Primary Information, 2022.

Araeen, Rasheed. “The Success and the Failure of the Black Arts Movement.” In Shades of Black: Assembling Black Arts in 1980s Britain, edited by David A. Bailey, Ian Baucom, and Sonia Boyce, 21–34. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005.

Archer, Michael. “Michael Archer in Conversation with Mona Hatoum.” In Archer et al., Mona Hatoum, 7–30.

Archer, Michael et al., eds. Mona Hatoum. 2nd edition, revised and expanded. London: Phaidon, 2016 [1997].

Bailey, David A., Ian Baucom, and Sonia Boyce, eds. Shades of Black: Assembling Black Arts in 1980s Britain. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005.

Bellan, Monique. “Ruptures and Continuities: Lebanon’s Art Galleries in the 1980s with a Focus on Galerie Damo (1977–88).” Manazir Journal 7 (2025): 21–56. Accessed in pre-publication format 22 May 2025, https://doi.org/10.36950/manazir.2025.7.2.

Bolmey, Sou-Maëlla. “Discours divergent chez Rasheed Araeen: ‘L’écriture et la publication comme travail artistique conceptuel.’” In Quand l’artiste se fait critique d’art: Échanges, passerelles et resurgences, edited by Ophélie Naessens and Simon Daniellou, 93–108. Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes, 2015.

Brett, Guy. Kinetic Art. London: Studio-Vista; New York: Reinhold Book Corporation, 1968.

Brett, Guy. “Survey.” In Archer et al., Mona Hatoum, 33–65.

Chambers, Eddie. Black Artists in British Art: A History since the 1950s. London: I. B. Tauris, 2014.

Chambers, Eddie. “Re-reading Black British Artists’ Practices: Black Artists and the Fetishization of the 1980s.” Lecture at the Knight Foundation Art + Research Center, 13 May 2021. Posted 8 November 2021, by the Institute of Contemporary Art Miami. YouTube, 1:11:38. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XZMbOJvEQQ8.

Collective, eds. “Rasheed Araeen.” In Roadworks. London: Brixton Art Gallery, 1985, n.p. Catalogue of an exhibition held at the Brixton Art Gallery, 18 May–8 June 1985.

Cooke, Rachel. “Mona Hatoum: ‘It’s All Luck. I Feel Things Happen Accidentally.’” The Guardian, 17 April 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/apr/17/mona-hatoum-interview-installation-artist-tate-modern-exhibition.

Correia, Alice, ed. What Is Black Art? Writings on African, Asian and Caribbean Art in Britain, 1981–1989. Dublin: Penguin Books, 2022.

Dalal-Clayton, Anjalie. “Coming into View: Black Artists and Exhibition Cultures 1976–2010.” PhD diss., Liverpool John Moores University, 2015.

Diamond, Sara. “Performance: An Interview with Mona Hatoum.” Fuse Magazine 10, no. 5 (1987): 46–52. Accessed 21 April 2025. http://openresearch.ocadu.ca/id/eprint/1792/.

Engelhardt, Julia. “Chronology.” In The Other Story: Afro-Asian Artists in Post-War Britain, edited by Rasheed Araeen, 128–41. London: South Bank Centre, 1989. Catalogue of an exhibition held at the Hayward Gallery, London, 29 November 1989–4 February 1990; Wolverhampton Art Gallery, Wolverhampton, 10 March–22 April 1990; and Manchester City Art Gallery and Cornerhouse, Manchester, 5 May–10 June 1990.

Fowle, Kate. “Missing History.” In Rasheed Araeen, edited by Nick Aikens, 295–303. Gateshead: BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art; Moscow: Garage Museum of Contemporary Art; Geneva: MAMCO, Musée d’Art Moderne et Contemporain; Eindhoven: Van Abbemuseum, 2017.

Gilroy, Paul. There Ain’t No Black in the Union Jack: The Cultural Politics of Race and Nation. London: Hutchinson, 1987.

Hall, Stuart. “New Ethnicities [1988].” In Selected Writings on Race and Difference, edited by Paul Gilroy and Ruth Wilson Gilmore, 246–56. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2021. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1hhj1b9.16.

Hall, Stuart et al. Policing the Crisis: Mugging, the State and Law and Order. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1978.

Hall, Stuart. Selected Writings on Race and Difference, edited by Paul Gilroy and Ruth Wilson Gilmore. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1215/9781478021223.

Hassan, Salah M., and Chika Okeke-Agulu, eds. “Black British Art Histories.” Special issue, NKA Journal of Contemporary African Art 49, no. 2 (2019).

Hatoum, Mona. “Body & Text.” Third Text 1, no. 1 (Autumn 1987): 26–33.

Hatoum, Mona. Email correspondence with Joan Grandjean, 16 June 2025.

Hatoum, Mona. Email correspondence with Joan Grandjean, 16 November 2025.

Hatoum, Mona. Interview by Joan Grandjean, 2 July 2024.

Hurman, Andrew. “Brixton Art Gallery Archive, 1983–1986.” Homepage. Accessed 17 April, 2025. https://brixton50.co.uk/.

Hurman, Andrew. “Creation for Liberation: 2nd Open Exhibition by Black Artists.” Catalogue of the Brixton Art Gallery Archive. Accessed 17 April 2025. https://brixton50.co.uk/creation-for-liberation/.

Hurman, Andrew. Email correspondence with Joan Grandjean, 24 June 2025.

Hurman, Andrew. “Multiples: Photography, Xerox & Edition-Based Media.” Catalogue of the Brixton Art Gallery Archive. Accessed 17 April 2025. https://brixton50.co.uk/multiples/.

Hurman, Andrew. “Third World Within: AfroAsian Artists in Britain.” Press release and catalogue of the Brixton Art Gallery Archive. Accessed 17 April 2025. https://brixton50.co.uk/third-world-within/.

Kayani, Amina. “Stranding the Audience: On the Performances and Installations of Mona Hatoum and Adrian Piper.” Full Bleed 5 (2021): n.p. Accessed 22 May 2025. https://www.full-bleed.org/stranding-the-audience.

Lebanese American University. “History.” Accessed 11 September 2024. https://www.lau.edu.lb/about/history/.

Lippard, Lucy Rowland. Six Years: The Dematerialisation of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1973.

Maltzahn, Nadia von. “Heritage, Tourism, and the Politics of National Pride: The Baalbeck International Festival in Lebanon.” Quaderni storici: Rivista quadrimestrale 2 (2019): 371–89. Accessed 17 December 2024. https://doi.org/10.1408/96904.

Maltzahn, Nadia von. “Roundtable Discussion with Rose Issa and Mohammad El Rawas on the Exhibition Contemporary Lebanese Artists at London’s Kufa Gallery in Early 1988.” Manazir Journal 7 (2025): 248–65. Accessed in pre-publication format 22 May 2025, https://doi.org/10.36950/manazir.2025.7.10.

Orlando, Sophie. “British Black Art.” In British Black Art, 18–42.

Orlando, Sophie. British Black Art: Debates on Western Art History. Translated by Charles La Via. Paris: Dis Voir, 2016.

Parker, Riana Jade. A Brief History of Black British Art. London: Tate, 2021.

Re.Act Feminism: A Performing Archive. “Mona Hatoum: Under Siege.” Accessed 13 December 2024. http://www.reactfeminism.org/entry.php?l=lb&id=65&wid=292&e=t&v=&a=&t=.

Said, Edward Wadie. Reflections on Exile and Other Essays. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001.

Saleh Barakat Gallery, ed. Beirut – The City of the World’s Desire: The Chronicles of Waddah Faris (1960–1975). Beirut: Salim Dabbous, 2017. Catalogue of an exhibition held at the Saleh Barakat Gallery, Beirut, 19 May–29 July 2017. Accessed 14 December 2024. https://salehbarakatgallery.com/Content/uploads/Exhibition/4938_Saleh%20Barakat%20Gallery%20Waddah%20Fares%20Catalogue%20low%20res.pdf.

Sebestyen, Amanda, Homi Bhabha, and Sutapa Biswas. Reviews of The Other Story: Afro-Asian Artists in Post-War Britain, 1981–1989, curated by Rasheed Araeen. In Correia, What Is Black Art?, 288–300.

Sivanandan, Ambalavaner. “From Resistance to Rebellion: Asian and Afro-Caribbean Struggles in Britain.” Race & Class 23, no. 2–3 (1981): 111–52.

Sulter, Maud, ed. Passion: Discourses on Blackness and Feminism. London: Urban Fox Press, 1990.

Szczelkun, Stefan. “Panel 3 – Archive and Contexts (Followed by a Discussion).” Plenary session at the symposium Activating Brixton Art Gallery, 1983–86: Archives and Memories. University of Westminster, London, 5 June 2010. Proceedings updated June 2023, accessed 21 April 2025. https://stefan-szczelkun.blogspot.com/2012/05/activating-brixton-art-gallery-1983-86.html.

Tate. “British Black Arts Movement.” Art Terms. Accessed 1 April 2025. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/b/british-black-arts-movement.

Wainwright, Leon. Phenomenal Difference: A Philosophy of Black British Art. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2017.