This article examines the curatorial approaches and exhibition practices of Beirut’s Sursock Museum during the 1980s, a decade marked by civil war and socio-political fragmentation. Following a seven-year closure, the museum reopened in 1982 and resumed a limited but symbolically charged programme. The study explores how the institution navigated inclusion, representation, and legitimacy in this fraught period, focusing on logistical constraints in a divided city, the formalist strategies of group exhibitions—especially the Salons d’Automne—and shifting criteria for artistic recognition. Drawing on archival material, press coverage, and curatorial documents, it positions the museum’s wartime programming as a case of institutional resilience, symbolic manoeuvring, and cultural gatekeeping. Particular attention is given to the perspectives of excluded or self-excluded artists, such as Mahmoud Amhaz, Mohammed al-Kaïssi, and RoseVart, whose critiques complicate the museum’s claims to neutrality. By interrogating jury composition and the political and aesthetic implications of their choices, the article contributes to debates on institutional critique, historiographic curating, and canon formation during conflict, reframing the 1980s as a contested terrain of curatorial agency and cultural significance rather than a lost wartime decade.

Sursock Museum, Salon d’Automne, Lebanese Civil War, Inclusion and Exclusion, Cultural Production in Conflict

This article was received on 13 January 2025, double-blind peer-reviewed, and published on 17 December 2025 as part of Manazir Journal vol. 7 (2025): “Defying the Violence: Lebanon’s Visual Arts in the 1980s” edited by Nadia von Maltzahn.

The Sursock Museum, Beirut’s museum of art that first opened in 1961, reopened to the public in the autumn of 1982 after a seven-year closure following the outbreak of the Lebanese Civil War in 1975. Founded through the bequest of Nicolas Ibrahim Sursock (1875–1952), a member of one of Beirut’s leading Greek Orthodox families, the museum was conceived as both a cultural gift and a cosmopolitan showcase; it became both a symbol of elite patronage and a locus of artistic recognition. Located in East Beirut in what was then a divided city, the museum in the 1980s was embedded in many of the broader socio-political dynamics of Lebanon’s conflict. Its efforts to navigate this turbulent decade—while grappling with shifting forms of representation and artistic value—offer a lens through which to view the complexities of cultural production during wartime. This article approaches the museum’s curatorial and institutional strategies, and exhibition practices in this period as shaped by logistical pragmatism and pre-existing institutional networks, but also considers how debates around inclusion and exclusion were increasingly framed in aesthetic, rather than explicitly political, terms. It examines inclusion and exclusion at the museum as phenomena with aesthetic (formalism vs. figuration), political (sectarian and right/left affiliations), and social (elite vs. popular) dimensions. Rather than advancing a single linear argument, this study engages with a set of overlapping tensions surrounding institutional judgment, artistic legitimacy, and representational strategy in a time of fragmentation.

It traces three interrelated dimensions of the museum’s wartime operations: the logistical challenges of exhibition-making in a divided city (the actual effects of war on participation); curatorial gestures that sidestepped or aestheticized wartime realities (the disavowal of overt political engagement); and the tensions expressed by artists and critics navigating shifting criteria for inclusion (individual grievances). This analysis proceeds in five parts: beginning with a quantitative overview of exhibitions during the 1980s, it then examines the Sursock Museum’s group exhibitions—especially its Salons d’Automne—within the spatial and political divisions of Beirut. Subsequent sections address the reactions of critics and artists (both participants and those excluded), the composition and politics of the museum’s jury, and the challenges of evaluating artistic merit in such a fraught context. By embracing rather than resolving the contradictions that emerge, this study reflects the ambivalence and fragmentation that characterized not only the museum’s programming, but also Lebanon’s cultural and political landscape more broadly. It asks both how the museum operated and what it meant for it to operate at all.

While scholarship on modern and contemporary art in Lebanon has grown significantly over the past two decades, sustained studies of the Sursock Museum’s internal operations during the 1980s remain limited. This article builds on critical contributions in the field of institutional critique and historiographic curating, particularly those that address the museum’s role as both an arbiter of artistic legitimacy and a contested public institution. During the fifteen-year war, the museum was open to the public for seven years, from 1982 to 1989. This period has received little scholarly attention. In the official history of the Sursock Museum, Musée Nicolas Sursock: Le livre (Nicolas Sursock Museum: The book,1 which will subsequently be referred to as Le livre),2 it is addressed only briefly—in two paragraphs of the section Survivre par l’art: Guerres et paix au musée (Survival through art: Wars and peace at the museum) and a postscript to the section before it. The bulk of that section focuses on the postwar decade of so-called “peace,” a curatorial and editorial decision that aligns with the wave of state-sanctioned amnesty and amnesia that marked the 1990s.3 While Le livre provides key data regarding exhibition frequency and public programming, it is treated here not simply as a documentary source but as a self-authoring narrative—its silences, elisions, and selective emphases read as symptomatic of the museum’s broader institutional positioning.

This article draws on a triangulated methodology combining archival reconstruction, curatorial analysis, and critical historiography. In addition to Le livre, the research mobilizes a range of archival traces, including exhibition catalogues, jury instructions, and internal correspondence—especially from figures such as the curators Camille Aboussouan and Sylvia Agémian.4 Press coverage from the 1980s, including articles in An-Nahar and L’Orient-Le Jour, provides insight into how exhibitions were publicly framed and received during wartime. These materials are approached not as neutral documents but as historically situated artefacts, produced within—and contributing to—the institution’s discursive formation.

Recent curatorial projects have contributed significantly to this emerging discourse. Je suis inculte! (2023–24), curated by Natasha Gasparian and Ziad Kiblawi, critically revisited the Salon d’Automne’s exclusionary legacy by foregrounding artists who had been omitted from the museum’s narrative.5 Similarly, Beyond Ruptures, curated by Karina El Helou, explored the museum’s history through its fragmentary archives and latent contradictions—many of which resonate with the complexities addressed in this article.6 Through archival materials such as rejection letters and unrealized proposals, the exhibition reframed institutional silence as a key site of historiographic inquiry.

Nadia von Maltzahn’s work has been foundational in situating the Sursock Museum within broader socio-political frameworks. Her analyses of the Salon d’Automne highlight the contradictions embedded in the museum’s jury structure and aesthetic frameworks, where formalist neutrality often masked deeper logics of exclusion and hierarchy.7 Her essay “The Museum as an Egalitarian Space?” explicitly challenges the myth of institutional impartiality, emphasizing how the Sursock Museum served as a site of symbolic contestation rather than merely a space for representation.8 My own previous work has extended this critique by focusing on the museum’s administrative operations and the influence of figures such as Aboussouan and Agémian in shaping public programming. Through archival research and historiographic analysis, I have argued that the museum’s curatorial decisions in the 1960s reflected not only aesthetic preferences but also broader tensions around memory, authority, and national identity.9

Understanding the museum’s institutional positioning requires acknowledging the broader cultural dynamics outlined by Silvia Naef in A la recherche d’une modernité arabe, emphasizing Lebanon’s role as a bridge between Arab and Western modernities, often eschewing overtly nationalist aesthetics: “The conflicting interests of the various Lebanese sects regarding the country’s international status (its relations with the West and the Arab world, its position on Arab unity or unity with Syria) have prevented the birth of a common national consciousness among all Lebanese. This consciousness has been replaced, in most cases, by sectarian loyalties that have shaped Lebanon’s cultural history and life.”10

By contributing to this growing discourse, the article reclaims the 1980s as a period of curatorial experimentation, institutional uncertainty, and symbolic tension. It begins by returning to the few official references to the decade, such as Agémian’s note in Le livre that “the list of exhibitions carried out clearly shows the downtime imposed by the dangers of the war that had resumed in Lebanon,”11 before examining what that list actually reveals—and what it omits—about the museum’s self-presentation during the conflict.

The museum had sixteen exhibitions12 in the seven years it was open in the 1980s, making it the lowest average of exhibitions per year for the museum in the second half of the twentieth century.13 However, it could be argued that, in many other ways, the 1970s was the most disrupted and disruptive decade for the museum that half century. The decade started with the museum closed due to its first expansion project, which started in 1969. It reopened to the public in 1974 for only one year, and closed again at the start of the war in 1975. That decade the museum also experienced a major shift in its leadership—the first since the museum’s founding. Camille Aboussouan was the curator of the museum from its inception in 1960 until 1978, when—three years into the war—he was appointed permanent delegate ambassador of Lebanon at UNESCO in Paris.

While Aboussouan was officially succeeded as curator by Loutfalla Melki in 1980, it is clear from the museum’s archival documents that the person truly steering and powering the museum at the time was Sylvia Agémian, who in 1975 went from researcher and artistic assistant to deputy curator of the museum. In the fall of 1979, for instance, she authored two key internal documents for the museum’s operations during that pivotal period: the first on “Artistic activities: Notes and proposals on the work likely to be carried out at the Sursock Museum in the absence of exhibitions”14 and the second on “Work concerning the museum library.”15 It was also Agémian who authored the plan for the reopening of the museum with the tenth Autumn Exhibition in the autumn of 1982.16 The Autumn Exhibition (Salon d’Automne) was “a group exhibition of contemporary art in and from Lebanon,” for which the Sursock Museum became known since its opening in 1961.17

In addition to the relative dearth of exhibitions imposed by the challenging circumstances of the war, the 1980s were marked by a shift in the nature of exhibitions. The 1960s, in addition to being the most active decade for the museum in the second half of the twentieth century, had offered the most varied mix of exhibitions: European (45%); Lebanese (21%); regional/Arabic (17%); and global (17%).18 By contrast, exhibitions in the 1980s were limited to the first two categories, with European exhibitions staying nearly the same (42%), while Lebanese ones formed the rest (and majority), climbing notably higher (to 58%). That considerable proportion of Lebanese exhibitions increased slightly (to 64%) the following decade (in the 1990s), while that of European ones reached the lowest proportion that half of the century (28%).19

Exhibition | Year | Date | Location | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

The Book and Lebanon | 1982 | 18–30 January | Paris (UNESCO) | |

Arabic Art in Spain (photographs) | 1982 |

| Spain | |

Tenth Salon d’Automne | 1982–83 | 21 December– | Beirut | |

Lebanese Architecture from the 15th to the 19th Century | 1984 | 5 June– | Paris * | |

Tribute to Nadia Tuéni | 1984 | 17–27 October | Beirut | |

Eleventh Salon d’Automne | 1984–85 | 21 December– | Beirut | |

Lebanese Architecture from the 15th to the 19th Century | 1986 | 10 April– | Beirut | |

Twelfth Salon d’Automne | 1986–87 | 16 December– | Beirut | |

Horst Janssen | 1987 | 12 June– | Beirut | |

Philippe Mohlitz, Engravings | 1987 | 2–3 December | Beirut | |

Thirteenth Salon d’Automne | 1987–88 | December–January | Beirut | |

Arabic Art in Spain (photographs) | 1988 | 25–30 March | Beirut | |

Elly Ohns Quennet and Dagmar Schenk Güllich, Engravings | 1988 | 10–20 May | Beirut | |

Contemporary French Graphic Art | 1988 | 14–30 October | Beirut | |

1988 | 14–30 October | Paris | ||

Fourteenth Salon d’Automne | 1988–89 | December–January | Beirut | |

* Académie Diplomatique Internationale (5–15 June), Hôtel de Sully (24 July–24 August) and Bibliothèque Nationale (12 October–30 November). | ||||

Looking beyond the numbers at the types of exhibition, it seems the choice was largely governed by pragmatism and relying on the networks already established by the museum in the first two decades of its existence. The vast majority of the European exhibitions in the 1980s (four out of five) was of engravings or graphic art by French and German artists (see Table 1), which were more mobile (and less valuable) than paintings and sculptures. And aside from the five Salons d’Automne, two of the three remaining Lebanese exhibitions were curated by the former curator, Aboussouan, from Paris—and in the case of one, The Book and Lebanon: Four Thousand Years of Humanism, presented in Paris only, before the reopening of the museum in Beirut at the beginning of 1982. According to Agémian, Aboussouan “had always dreamed of publishing two major works: one dealing with the history of books in Lebanon and the other on Lebanese architecture since the 15th century.”20 Amine Beyhum, mayor of Beirut who was mutawalli (legal custodian)21 of the museum from 1962 until his death in 1981, “asked him to associate the name of the Sursock Museum” with these projects.22 This conveys to what extent the personal preferences of the former curator continued to dominate the museum’s curating practices in the 1980s. It also suggests that the museum board, presided by the mayor of Beirut, was looking at ways to keep the museum active during the war.

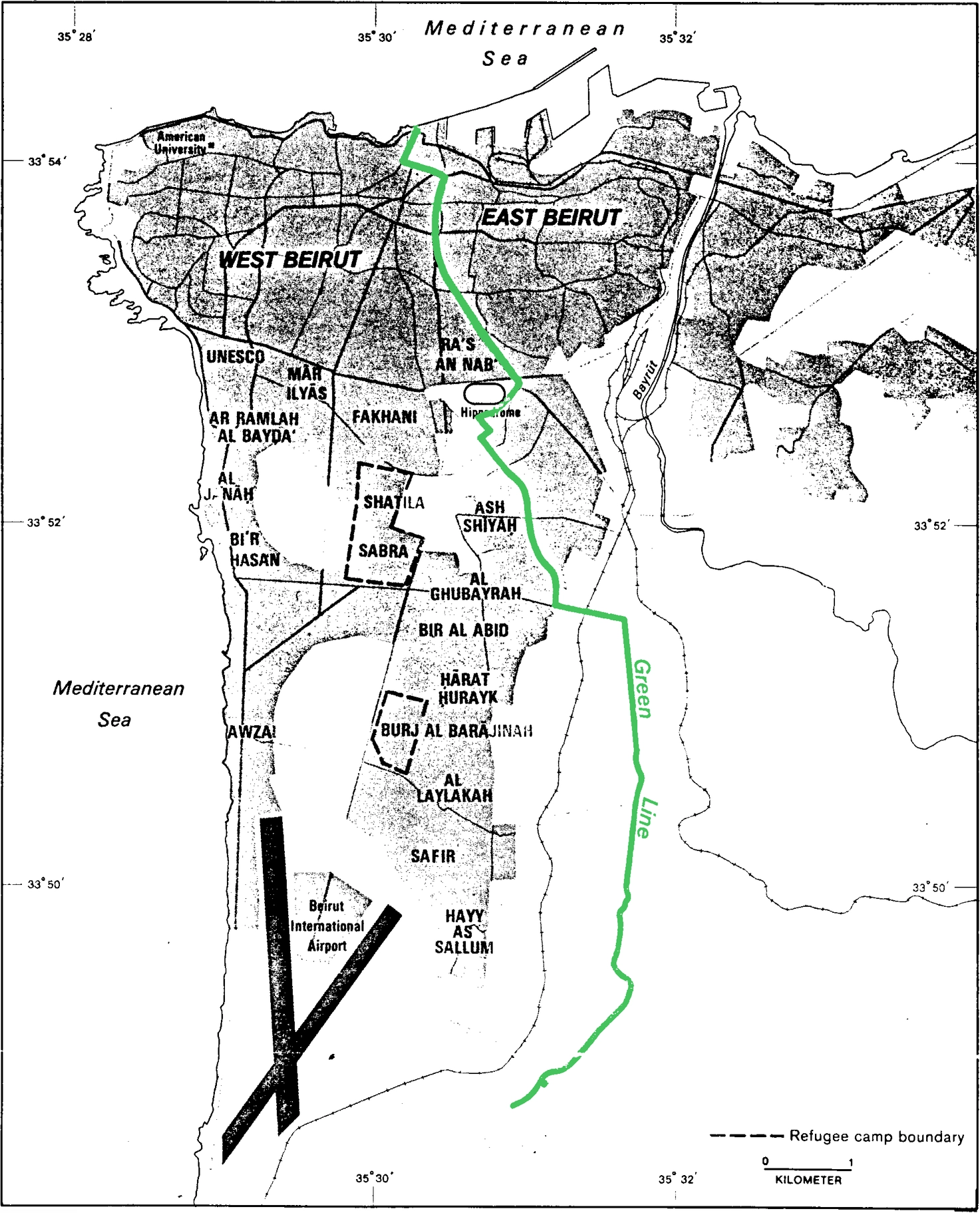

Thanks to the continued collaboration with Aboussouan, a quarter of all exhibitions that decade took place abroad. This was higher than in any other decade that half century: in the 1960s and 1990s exhibitions abroad constituted only 7 per cent of the total (there was none abroad in the 1970s). “Was it ‘written’ that this museum, already forced to go extramural to make its debut with its ‘imaginary exhibition’, must also, to continue, ‘emigrate’ with its curator?,” Agémian asks in Le livre.23 Accordingly, three out of those four exhibitions were in Paris. It is worth noting that this extramural “imaginary exhibition”24 debut in 1957 had taken place at Beirut’s UNESCO Palace, located in what, during the 1980s, had become West Beirut in a divided city (fig. 1). The artworks for that first exhibition were also stored there, and were unfortunately destroyed during the Israeli invasion of 1982.25 Throughout the 1980s, however, there were no Sursock Museum exhibitions in the western part of the city. If you lived in Paris in the 1980s, you had better chances of attending a Sursock Museum exhibition than if you lived on the other side of Beirut.

The list of exhibitions suggests that the museum during this decade took advantage of opportunities presented to it, be it in the form of cooperation with European cultural institutes or reverting back to its formative curator Aboussouan, despite him having moved to Paris. Its main focus in terms of exhibitions in Beirut remained its Salons d’Automne, the museum’s flagship showcases of local art. Looking at these in more depth allows us to tease out how the museum dealt with questions of identity, representation, and artistic value.

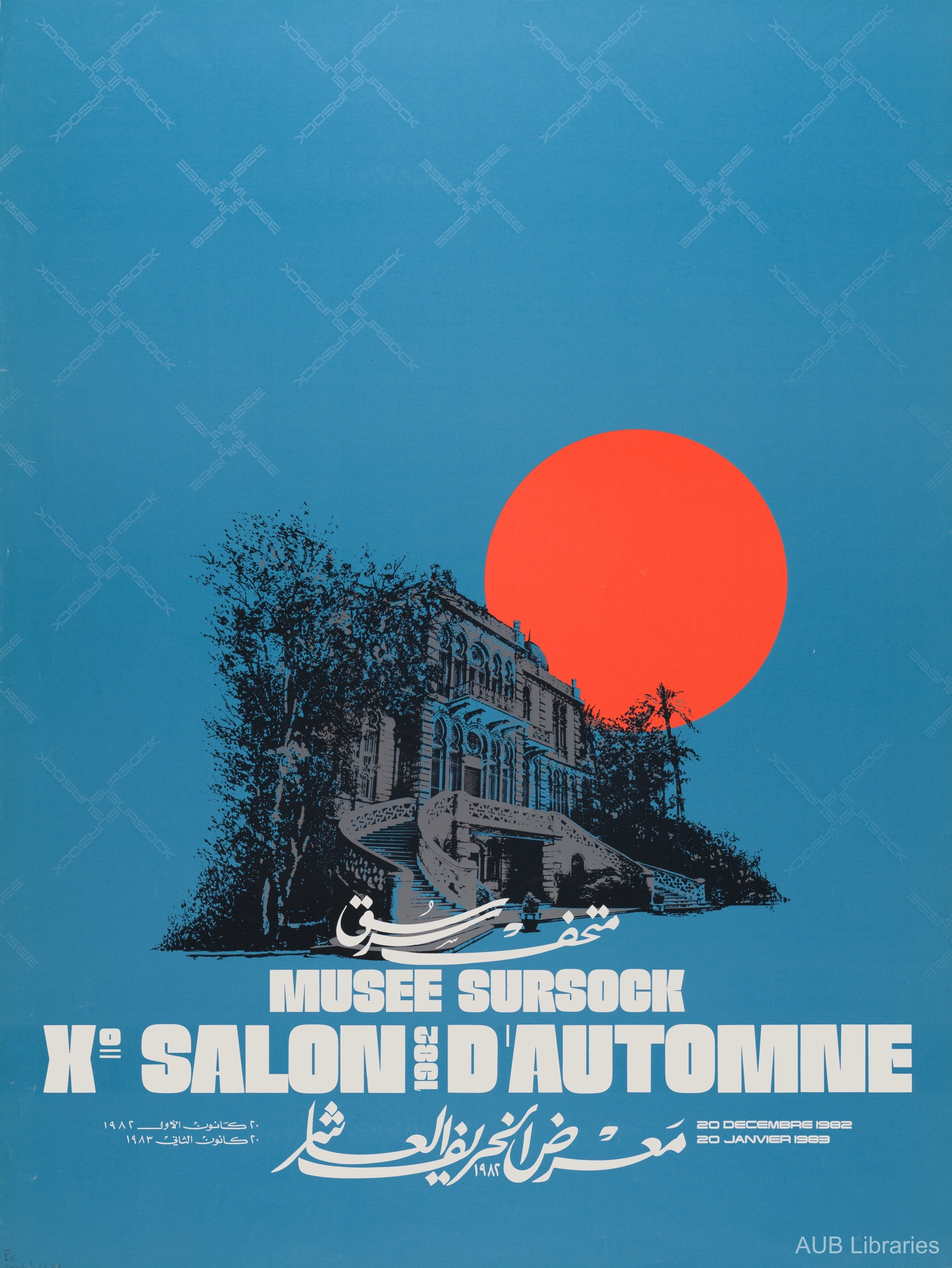

Israel’s 1982 invasion, officially aimed at dismantling Palestinian armed groups, devastated much of Lebanon’s infrastructure and intensified the country’s sectarian fractures. The war not only resulted in large-scale human displacement, but also deepened Beirut’s east-west division, impacting the circulation of people, goods, and cultural production across the city. The divide in the city was limited not only to the viewing of exhibitions, but extended as well to participation in them. After seven years of closure to the public since the start of the war, the museum reopened in December 1982 with the tenth edition of the Salons d’Automne, announced with “a glorious poster”26 by Saad Kiwan, depicting a large orange disc behind the museum building. It was supposed to represent the “sun rising above the museum”27 (though with its placement to the west of the building, one would not be entirely wrong to mistake it for a sunset) (fig. 2), in “times that seemed to allow hope for a return to normalcy,”28 according to Agémian, but for the first time in a city divided in two.

While Agémian’s reflections in Le livre offer valuable insight into the museum’s wartime challenges, they must be situated within her role as an active agent shaping the institution’s self-narrative. As deputy curator, her portrayal of resilience and hope reflects not only institutional memory but also a strategic framing of the museum’s endurance during a period of profound national fragmentation. This alignment between personal recollection and institutional positioning is further evident in more recent critical assessments of the museum’s wartime programming. As noted in the exhibition Je suis inculte! The Salon d’Automne and the National Canon, the museum’s 1982 reopening—with the tenth Salon d’Automne—occurred a few months after the Israeli invasion and the Sabra and Shatila massacre. Yet, “the war was only glimpsed in the content of paintings and sculptures at the salon—the aesthetic program was enduringly formalist.”29 The museum, the exhibition argues, continued to see itself as an “enlightener amid the darkness of civil war,”30 selectively foregrounding formalist aesthetics over direct engagement with the surrounding devastation. Agémian’s comments, therefore, can be read as part of a broader institutional strategy to emphasize cultivation, continuity, and resilience—at times, at the expense of confronting the immediate political and human crisis outside its walls.

The reopening was “an event in itself, marking the resumption of activities of the only truly living museum in Beirut, whose absence has been keenly felt in recent years in the field of major exhibitions,” wrote the art critic Joseph Tarrab in a three-part series in the main French-language newspaper, L’Orient-Le Jour. “Just for having undertaken to fill this void so quickly, the museum committee is entitled to the recognition of art lovers.” He admits, however, that “the very speed of setting up this first major postwar event did not allow, in the current state of things, to contact all the interested artists, because of the difficulties of communication, many of them being either abroad or in their villages.”31 The new curator of the museum then, Loutfalla Melki, referenced this diasporic spread of the artists in the catalogue: “from all regions of Lebanon, as well as France and Italy, our artists sent their creations, making of this museum the meeting point and the melting pot of Lebanese art.”32 However, for the first two war editions, artists in the western part of the city wanting to submit their art for consideration had to transport it across treacherous checkpoints to the museum in the eastern part, and back. Possibly due to that, and the frustration of the war that raged on, the second of those editions (the eleventh Salon d’Automne, in 1984) saw a drop in exhibited works to less than a quarter of the prior one (forty-one compared to 125), making it the smallest Salon d’Automne ever.

That changed with the twelfth Salon d’Automne in 1986, when artists were given the option to drop off their work in West Beirut at the Lebanese Artists Association for Painters and Sculptors (LAAPS) in Verdun. That year, eleven artists took advantage of that option, eight of whom were included in that salon. For half of those, it was their first ever participation; and for three of those four, it would be their last that decade.33 The following month, one of those artists, Fayçal Sultan, who was an art critic for As-Safir newspaper, wrote in a review of the museum’s output that, despite the museum’s open invitation to everyone to participate, and even Agémian’s move to facilitate the possibility of collecting and transferring works from the western region, the outcome was disappointing. Artists—from both sides of the dividing line—chose not to participate for various reasons, including the difficult security conditions, not wanting to subject their works to the “whims of the judging committees,” and a general indifference to group exhibitions.34 While the security situation and possibly the indifference to group exhibitions were related to wartime conditions, reactions to the perceived bias of the jury were nothing new and had accompanied the salons since their inception.

The perceived bias of the jury was rooted not simply in personal preferences but in deeper structural alignments. The museum’s committees historically favoured formalist abstraction and a Francophile cultural orientation, reflecting broader nationalist and socio-political currents. As von Maltzahn argued in “Guiding the Artist and the Public?,” and the museum’s own Je suis inculte! exhibition later highlighted, the aesthetic programme of the Salon d’Automne maintained a formalist and nationalistic tone even amid the devastation of the civil war, framing art as an instrument of “cultivation” and “hope” while largely avoiding direct engagement with the violence unfolding outside its walls.

No matter the reasons, in that year (1986) participation in the Salon d’Automne bounced back to just above average for the decade (ninety-two compared to eighty-nine works per salon), though that remained lower than the average for the five decades that century (122). The following year, the West Beirut location was changed to the office in Barbir35 of the mutawalli of the museum, Shafiq Sardouk. No information was available on participants from West Beirut that year, although we know that overall participation dropped back below average (to seventy-five works). As well preserved as the museum archives are, they can only begin to hint at how war complicated the logistics of running these salons, the different ways the museum tried to cope with the divisions in the city (and the country), and how that may have impacted the submissions.

What is perhaps most remarkable in the references to the salons of the 1980s, however, is the absence of the context of war, except maybe in passing as a euphemism (such as “dark clouds darkening the sky” or “difficult and dark years”)36 or cause of pragmatic difficulties (as in the earlier quotes by Agémian and Tarrab), but not as an overwhelming existential challenge. Otherwise, much of the prewar debates—about abstraction and figuration, inclusion and exclusion, old and new, the safe and the challenging—continued unabated. One of the few art critics to point this out about the first salon of the decade was Nazih Khater who, in the first of a four-part series in An-Nahar focusing on the museum’s reopening, wondered whether one remembered that a war had taken place in Lebanon and was still ongoing, as a visitor to the Salon d’Automne might not guess it by looking at the works. Khater wrote that he was not judging this, and that every artist was free to choose what to depict:

How to pass by a group exhibition in December 1982 and not note the absence of the war’s human features from its details? And at least its human flavour? What does an artist draw if he distances his sight from his conscience? All of this brings us to a question about the meaning of an exhibition like this at the beginning of the 1980s of the end of the twentieth century. That is, the question that contains in its question mark the rest of the questions. Would we be harsh on it if we said that the tenth Autumn Exhibition is one of reassurance?37

In this context, “reassurance” can be understood as both an aesthetic and a political gesture. At a time when Lebanon was experiencing extreme violence, displacement, and social fragmentation, an exhibition that largely avoided representing war might have offered visitors a sense of stability, continuity, or escapism—an affirmation that beauty, culture, and artistic production could endure. Yet this very gesture could also be seen as alienating or conservative: by emphasizing aesthetic formalism and avoiding direct engagement with the country’s trauma, the museum risked appearing disconnected from the lived realities of the majority of the populace. Reassurance, then, was double-edged: it could comfort some, but also signal a retreat into insularity and denial, raising difficult questions about the role of cultural institutions during periods of profound national crisis.

This critique of alienation from context is reminiscent to one levelled against the museum and its salon eighteen years earlier. In a 1964 Magazine article titled “Je suis inculte!” (I am uncultivated!), Jalal Khoury asked whether a citizen of the world who was dropped in the middle of the Salon d’Automne of the Sursock Museum would be able to know where they were just by looking at the paintings around them.38 Taking this article as the starting point for their exhibition, curators Gasparian and Kiblawi noted that, in the 1980s, the museum’s aesthetic programme being formalist was the museum’s attempt to maintain neutrality during the war.39

The salon catalogues from that decade reflected subtle yet significant political alignments through their choice of epigraphs. The 1982 Salon opened with a quotation from then-president Amine Gemayel, emphasizing Lebanon’s capacity for “extraordinary renewal and perpetual rebirth” through cultural creativity. At the time, Amine Gemayel had just assumed the presidency of Lebanon following the assassination of his brother Bashir Gemayel. As a leading figure of the right-wing Phalangist Party, his presidency embodied a Christian nationalist project that blamed the Palestinian presence for much of the country’s descent into war, and sought to restore a Christian-dominated political order. Similarly, the 1987 Salon cited Michel Chiha, presenting Lebanon as a “predestined country” endowed with “human qualities” and “resources of intelligence.”40 Michel Chiha, whose writings deeply shaped mid-twentieth-century Lebanese political thought, articulated a vision of Lebanon as a unique, pluralistic, but ultimately Christian-anchored society. His emphasis on human resourcefulness and resilience was often used to affirm Lebanon’s exceptionalism in the face of regional upheavals.

While the museum may have aimed for neutrality, the invocation of such figures—especially at a time of profound national division—carried enough cultural subtext to suggest the museum’s political positioning, however discreetly framed. Given that the museum resumed its exhibitions after the expulsion of the Palestinian leadership from Lebanon following the Israeli invasion in June 1982—a moment that, in the discourse of right-wing, largely Christian factions, was framed as the “restoration of sovereignty” and the end of a major cause of the war—the catalogues give insights into the museum’s political positioning. The expulsion of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) leadership from Beirut in the summer of 1982, following the Israeli invasion, dramatically altered the city’s political terrain. The withdrawal weakened the Palestinian and leftist presence in West Beirut, while allowing Christian forces to consolidate control over East Beirut—the side of the city where the Sursock Museum is located. As Nadia von Maltzahn has suggested, “the hopeful tone and the statement that now peace had returned clearly inscribes the Museum into the—right-wing, largely Christian—camp that blamed the Palestinians for the war.”41

While the war was largely absent from the content of the exhibitions, it was nevertheless present in homages to deceased artists that became integral to the salons in the 1980s. The format of an homage within the salon was not novel to the decade; it had started in the mid-1960s with memorial tributes to departed pioneering artists, César Gemayel and Moustafa Farroukh, in the fifth and sixth salons, respectively (the artists had died in the late 1950s). The homages did not continue, however, with the following editions, until its return in the 1980s.

SA | DATES | HOMAGES | JURY |

|---|---|---|---|

10 | 20/12/1982–20/1/1983 | Farid Aouad (1924–82), Hussein Badreddine (1939–75), Michel Basbus (1921–81), | Aimée Kettaneh, Pierre al-Khoury, Abdul-Rahman Labban, Joseph Rabbat, Rickat Salam, Samir Tabet, Georges Tohmé |

11 | 21/12/1984–21/1/1985 | [none] | Sylvia Agémian, Nazih Khater, Pierre al-Khoury, Hind Sinno, Joseph Tarrab |

12 | 16/12/1986–31/1/1987 | Sophie Yeramian (1915–84) | R.P. Abdo Badaoui, Rafiq Sharaf, Hussein Madi, Joseph Rabbat |

13 | 12/1987–1/1988 | Alfons Philipps (1937–87) | R.P. Abdo Badaoui, Rafiq Sharaf, Pierre al-Khoury, Hussein Madi, Joseph Rabbat |

14 | 12/1988–1/1989 | Fadi Barrage (1939–88), | Sylvia Agémian, Pierre al-Khoury, Hussein Madi, Joseph Rabbat, Joseph Tarrab |

Another tradition from the salons of the 1960s, the prizes, was also halted the following decade, in the 1974 Salon, when the curator, Aboussouan, announced, “No prizes, only acquisitions, until we have a decent collection.”42 That remained the case throughout the 1980s, until after the war. So, while the 1960s was the decade of prizes (a total of forty-seven, compared to fifteen in the 1990s), the 1980s was the decade of homages (a total of ten, compared to six in the 1990s, two in the 1960s, and none in the 1970s). While artists commemorated in the 1980s were not explicitly described as war casualties—Fadi Barrage, for example, honoured in 1988, was one of the first artists in Lebanon to die of AIDS complication—the act of posthumous homage nonetheless contributed to the overall tone of loss and mourning that characterized the period. The absence of prizes, which had marked the previous decade, was attributed by Aboussouan to the museum’s desire to build a collection before awarding distinctions. Yet it is also plausible that the economic uncertainty and infrastructural instability caused by the war itself made monetary awards impractical or inappropriate. Together, these gestures of homage and abstention from awarding prizes contributed to the museum’s sombre and arguably evasive stance toward the war’s immediate realities.

The Absent, the Refused, the Missing

It is perhaps not so surprising then that after such a long absence43 and in the midst of war, absence itself would play a prominent role in the reception of the salons. In fact, the first section in the first instalment of Tarrab’s aforementioned three-part series in L’Orient-Le Jour is titled “The absent, the refused, the missing.” In it, he describes the groups of absentee artists: first, there are “those who, having died during the war through violent death or illness, would certainly have participated if they were still among us” (and accordingly were honoured in homages); then, there are “two important categories of known or established artists: those who were too modest and reserved to come forward on time […] and those who were blessed abroad for several years”; and lastly, there are “those refused.”44 We will come back to the second category; for now, let us consider the last, the refused. The catalogue of the museum’s tenth Autumn Exhibition stated that “360 works by 140 artists were presented. 103 works by 66 artists were selected.”45 So, while less than a third of the works presented were selected (29%), nearly half of the artists were accepted (47%). Tarrab considered that to be “a sign of health, without doubt, and a measure of the moral prestige of the Salon” and lamented the “laxity of collective and private exhibitions in recent years.” He admitted: “the fact remains that this is one of the most effective ways for strangers to get noticed if they are selected.” And he continued:

It would perhaps be interesting and very instructive on the state of pictorial attempts among budding artists to organize, in parallel with the Salon d’Automne, a counter-Salon des refusés, which would allow everyone to judge the merits of the jury’s decisions: but there is reason to fear, given the massive craze for bad painting, that the success of this counter-exhibition, which risks turning into a fair, will eclipse that of the official Salon. But, in fact, don’t we already have such a salon (or almost) with that of Printemps?46

The Salon du Printemps was that held since 1953 by the Ministry of National Education and Fine Arts, alongside a Salon d’Automne introduced by the ministry the following year, which it later discontinued. And as in the Sursock salon, “the ministry appointed a jury that consisted of cultural figures (including architects) as well as of artists.”47

Not everyone agreed with Tarrab’s assessment, however. Three days later, in the first instalment of his aforementioned four-part series in An-Nahar, Khater wrote on the strictness in the selection of the Sursock Museum’s committee. Although not knowing who was actually turned down, Khater notes that many artists were excluded from showing their work in the salon. While he appreciated the quality of the works as well as their display (“serious scientific museal standards”), and that attendance was free, he wondered why some artists were selected when others were not.48 A few days later, in the second instalment of the series, Khater presented another reading on those absent from the salon, elaborating on the role of the museum, and questioning that of the jury:

Is it the role of the museum, no matter how stringent it is in its choice, to hold a group exhibition using the logic of galleries? How can a museum accept subjecting professional visual artists with recognized creativity to a jury ruled by amateurism? For example, does the museum need Mrs Aimée Kettaneh, Mr Rickat Salam, Dr Abdul-Rahman Labban, Mr Samir Tabet, and Dr Georges Tohmé to accept the works of Shafic Abboud, Yvette Ashkar, Halim Jurdak, Elie Kanaan, Hussein Madi, and Nadia Saikali? And then how are we surprised that a wide group of artists stays away? Should the museum not act within clear cultural visions that give its initiatives the extent of scientific selection for its end points? The difference between a museum’s collective exhibition and others’ exhibitions may be that the museum knows well and in principle what it wants to show in its initiative, and therefore it knows well who it wants to see in its exhibition.49

To a large extent, this does not differ much in essence from earlier discussions on the role of the jury and the museum, except perhaps in a notable shift in the identitarian critique of the jury members: from a foreign versus national axis earlier to gradations within the national end of the spectrum in the 1980s. We will return for a closer look at this towards the end of this article. For now, it is worth noting that in the following edition of the Salon d’Automne in 1984, both critics, Khater and Tarrab, were part of the selection jury, “in favour of supporting the second wave of modernism and restoring contemporary experimental painting to its avant-garde role in the museum.”50 The questions they raised remain central to considering the role of the museum in this period.

How was the museum then perceived by some of these absent artists, who either chose not to participate in the salons of that decade, or tried but were denied the opportunity? Let us start with an artist who had participated in all Salons d’Automne since 1964, but in 1982 chose no longer to do so. Mahmoud Amhaz, a professor of art history at the Lebanese University with a doctorate from the University of Liege in Belgium,51 who had taken part in the last six Autumn Exhibitions before the museum’s closure in 1974, chose not to participate in the exhibitions of the 1980s. In an interview in Al-Liwaa newspaper in December 1982, Amhaz explained his distance from the salons, lamenting that “artistic production has become artificial and commercial, concerned with appearances rather than profound artistic research.” He further noted that “the political situation in Lebanon does not provide a psychologically comfortable framework for the artist to work.” For Amhaz, participating in exhibitions under such conditions felt disingenuous, as “art has been reduced to an embellishment of daily life, divorced from its essential human and existential concerns.” He continued that “the participation of the artists was only a kind of encouragement for the security measures [the museum] hoped will succeed,” and generally considered Sursock’s salon outdated.52 Amhaz’s comment about “security measures” can be understood as referring to the broader attempts by institutions in East Beirut—such as the Sursock Museum—to project an image of stability, normalcy, and cultural continuity amid ongoing conflict and division. His critique suggests that, in his view, artists’ participation in the salon would serve less as a genuine artistic engagement and more as a symbolic endorsement of these efforts to “secure” public life through cultural programming, at a time when the realities of war and political fragmentation were still deeply unresolved.

Note here the resonance with Khater’s earlier critique of the tenth Autumn Exhibition as an act of “reassurance,” in Amhaz’s suggestion that artists’ participation served as “encouragement” and “hope” for stability. The concepts of reassurance, encouragement, and hope are invoked here as interpretive markers to capture the affective and symbolic dimensions of the museum’s wartime exhibitions. The rejection of the museum’s Autumn Exhibitions appears to stem from overlapping concerns—on one hand, the perception that the salons were becoming commercially driven, and on the other, a growing sense that the institution was no longer in step with evolving artistic sensibilities. Further on, however, while discussing his recent publication, Contemporary Fine Art (Painting: 1870–1970),53 Amhaz elaborated on connections between art and commerce, saying that “the traditional concept of the artwork as a commodity is one of the factors that pushed some artists to these negative positions,” such as the “absurd trends that led to what is called non-art.” He continued:

The art exhibitions that appeared in Europe […] consecrated the artwork as a commercial commodity in the exhibition hall with all its background issues (of advertising—financiers—publicity). All of these issues are negatives on the level of artistic production, which reduced it to the level of commerce, and led to the emergence of an artistic movement by artists to raise the level of art and return it to its natural place by producing (non-artistic) works represented by some modern trends.54

Amhaz continued to paint and show his work in commercial galleries, but he never again exhibited at the Sursock Museum that century. While his distancing from the salon can be partly attributed to the destabilizing effects of Lebanon’s ongoing civil war, his critique also reflected broader anxieties about shifts in the global art scene. In his view, the increasing commodification of art—exemplified by the European and North American market systems where galleries, advertising, and financial speculation began to dominate artistic value—had eroded the integrity of artistic production. His rejection of the salon thus intertwined a local disillusionment with wartime cultural life and a wider unease about the commercialization of art on a global scale.

Next, let us consider an example from the other end of the decade, this time from the archives of the museum, to further illustrate how tensions between artists and the Sursock’s jury structure persisted—and even deepened—throughout the 1980s. Mohammed al-Kaïssi is another artist, also a professor at the Lebanese University, who had participated in three Salons d’Automne (in 1962, 1982, and 1987) but whose 1988 entry was refused by the selection committee. In February 1989 he penned a page-long “Letter to the curators of the Sursock Museum,”55 a month after the fourteenth Autumn Exhibition ended. He opened with a regret that he felt there was a divide between Lebanon’s established artists and the museum, which he considered the main forum for gathering artists and displaying their works. His criticism of the 1989 Autumn Exhibition was particularly directed at a committee member whom he held responsible for “deleting and cancelling” an artist (namely himself) at the stroke of a pen, wondering whether “to make [his] fine painting disappear, and deprive many art connoisseurs and critics from seeing it, [was] the goal of the committee?” The artist then went on to describe the rejected painting in question, “a very important painting from the stages of [his] artistic life that spanned from 1950 to today. A thesis painting representing the suffering of Eastern women, an oil painting measuring 2.50 m × 1.00 m in a new fresco style, divided into 16 paintings.” Kaïssi continued by inviting the committee to “note that this painting was transferred from the Western region to the museum in a secure envelope, in the car of the mayor of Beirut, Mr Shafiq Al-Sardouk, and guarded by three security forces guards,” underlining the support received from the mayor, who was mutawalli of the museum after all.

In an effort to establish his worth, the artist then detailed his professional affiliations and the various places, in Lebanon and abroad, where his work had been shown, noting in particular that the first exhibition he participated in was the ministry’s Autumn Exhibition at UNESCO in 1954, “where the paintings of César Gemayel, Moustafa Farroukh, Omar Onsi, Saliba Douaihy, Georges Cyr, Rashid Wehbi, and other great artists were presented. We felt proud and appreciated, and at that time I received the Zalfa Chamoun Award.56 Where is the autumn of ’54 of UNESCO from that of Sursock ’89?” He concluded his letter with the following:

These are signs of the dwarfing of art in Lebanon. Have we really reached this level? Who is responsible?

I have decided to boycott the Autumn Exhibitions at the Sursock Museum, as long as there are people among the committee members whose aim is the destruction of talent and art in Lebanon.

I record this message for history as an artist […] preserving my personal right to do whatever I deem appropriate to correct my artistic position.57

It is worth noting that, two years later, Kaïssi did participate in the first Salon d’Automne after the war, the fifteenth, in 1991, as well as the following one. That was the fifth time he was selected by the jury, which qualified him then to become a member, or Sociétaire, thus allowing him hence to be admitted to the salon without being subjugated to the jury’s evaluation.58 Kaïssi returned as such to participate five more times that century. While the specific circumstances of Kaïssi’s renewed selection are not documented in available sources, it is plausible that the postwar restructuring of the cultural field—and the broader shift toward national reconciliation—eased previous tensions between artists and the museum’s jury. The reopening of the Salon d’Automne in 1991 may also have involved changes in jury composition or selection criteria, reflecting a new political and institutional climate in the aftermath of the war.

While Amhaz chose not to participate in the Sursock Museum’s salons starting in the 1980s, being disillusioned with the artistic direction he felt the museum had taken, and Kaïssi voiced his anger at being rejected by one single salon while being admitted to others, the example of another artist, RoseVart, questions more directly the selection criteria of the salon. Rosine Vartouhi Sissérian, better known as RoseVart, applied to the Salon d’Automne three times that decade (in 1982, 1986, and 1988; see fig. 3) only to be repeatedly rejected. She wrote about her experience in Le Reveil in January 1989 after visiting the museum’s salon, in an article titled “The Salon d’Automne: What Are We Looking For?” She opened the article with a description of two works at the Museum of Modern Art in New York by Kazimir Malevich that were exhibited for the first time in 1918 at the tenth State Salon in Moscow. The works titled Homage to the Vertical and Homage to the Horizontal consist of “two blank sheets of paper, square shaped, with a vertical line on the first and a horizontal line on the second, drawn finely with a lead pencil.” That is followed with an anecdote about a student of Amine Al-Basha, leading to the main question of the piece, “What is a good painting?” From there, she continued to relay her experience of submitting a number of her works in different media, including oil paintings, watercolours, gouaches, and tapestry, to the salon throughout the 1980s, in the hope of being admitted to what she called “this ‘sanctuary of art,’” but being consistently rejected. She wondered about the reasons for her rejection, as she had each time selected pieces reflective of her style and use of colours, grounded in her academic training and not offensive. “I don’t think I have intimidated or offended the members of the jury, as I did not present the nude of Manet’s Déjeuner sur l’herbe,” she noted, alluding to the latter’s infamous rejection by the Paris salon jury in 1863. RoseVart graduated from the Academie libanaise des Beaux-Arts (ALBA) with distinction in 1980, as she pointed out in the text, and had since been teaching there and serving on several of its juries. With this in mind, she asked: “On what basis beside genuine values, [do] mediocre works manage to be hanged on the picture rails in the Museum? On what basis and on what criteria do we choose our artists and artworks? It is certainly not with drawing lots that they decide what to choose.”59

![Sissérian, RoseVart. <i>Beyrouth ville martyre</i> [Beirut, the Martyr City]. 1986. Oil on canvas. 100 × 80 cm. Image courtesy of the RoseVart Collection. From Sonia Nigolian, <i>RoseVart… A Life Story</i> (Beirut: Photogravure Packlayan, 2000), 16–18.](https://bop.unibe.ch/manazir/article/download/11950/version/12250/15959/61790/dkc6q2zb314g.webp)

There is no easy explanation for RoseVart’s persistent rejection, at least not explicitly on political grounds. Her close affiliation with ALBA would have qualified her from a technical point of view, and her association with Le Reveil—the French-language daily newspaper launched by Amine Gemayel in 1977 to support Kataeb Party positions60—suggests she was not politically misaligned with the museum’s general cultural milieu. In the absence of concrete evidence linking her exclusion to political motives, it is more plausible that her rejection by the jury members was based on aesthetic preferences. However, the intertwining of aesthetic and political values within the salon’s history cautions against treating these domains as fully separate, especially given the broader cultural alignments operating during the war period.

The debates around inclusion and exclusion during the 1980s salons appear, based on the limited available evidence, to have been shaped more by aesthetic debates related to developments in contemporary art than by explicit political alignments. However, given the entanglement of aesthetic and political values in the Lebanese context, definitive conclusions remain difficult to draw. Was this “out of step” in the words of Dafoe, who argues that, once upon a time, an:

approach, which emphasizes an artwork’s physical properties (composition, colour, scale) over the external contexts of its making (the artist’s identity and intentions, say), was the dominant theoretical mode for much of the modernist era of the early twentieth century. But by the 1960s and ’70s, as new critical approaches—feminism, postcolonialism, structuralism—evolved in response to a cultural landscape shaped by political violence and burgeoning social movements, the formalists’ close-eyed approach seemed out of step.61

The tensions underlying the judgment of art in 1980s Beirut were symptomatic of a broader cultural rift: RoseVart’s formalist and technically grounded practice may not have aligned with the jury’s shifting preferences, while Amhaz’s critique of commercialism revealed an opposing frustration with perceived conservatism and market encroachment. These differing perspectives suggest a fragmented consensus about what contemporary Lebanese art should be—one that paralleled the fractured national context in which the museum operated.

The 1980s were not a monolithic period; the Lebanese Civil War evolved through shifting alliances among Christian and Muslim militias and political movements, Palestinian factions, and regional powers. Each phase of the decade—from the Israeli invasion of 1982 to the “War of the Camps” (1985–88) and the final battles of the late 1980s—altered the rhythms of violence and the spaces available for cultural life, including at institutions like the Sursock Museum. The politics of inclusion and exclusion at the museum in that conflicted decade emerge, based on the available testimonies and archival traces, as complex and difficult to decipher—mirroring in some ways the ever-shifting alliances of the fifteen-year war in Lebanon. Artists such as Mahmoud Amhaz, Mohammed al-Kaïssi, and RoseVart questioned not only their exclusion from exhibitions but also the opacity and subjectivity of the jury’s decisions, raising broader concerns about institutional legitimacy during a time of national fragmentation. Perhaps RoseVart was onto something when she asked, “On what basis and on what criteria do we choose our artists and artworks?” What criteria were applied? When Khater asks, “How can a museum accept subjecting professional visual artists with recognized creativity to a jury ruled by amateurism?” Who were these people in the jury? And what qualified them to judge another’s work? When Kaïssi wrote, “there are people among the committee members whose aim is the destruction of talent and art in Lebanon,” was this directed against some members in particular? Kaïssi’s frustration suggests he perceived the 1989 jury as more exclusionary than others. His rhetorical phrasing reflected a deep disillusionment with a process he believed was driven less by artistic criteria and more by personal antagonism or institutional opacity.

So, who was judging art at the Sursock Museum that decade? The museum jury was “generally composed of representatives of some of the fine art departments at national and private universities in Lebanon, as well as of art critics and, at times, the acting president of the Lebanese Artists Association for Painters and Sculptors (LAAPS).” By the 1980s its members had been mainly Lebanese.62 That decade, the jury of the Salon d’Automne (SA) ranged from four members (SA12, 1986–1987) to seven members (SA10, 1982–1983) at a time, the remaining three juries having five members each. In total, fourteen people were on the salons’ juries that decade, four of whom were women. Half of those fourteen participated more than once (see Table 2).

At the high end, with four contributions each, were Pierre el-Khoury (SAs 10, 11, 13, and 14) and Joseph Rabbat (SAs 10, 12, 13, and 14). El-Khoury was a prolific architect and graduate of the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. Rabbat, an interior architect and founder of the School of Decorative Arts at ALBA, was also an alum of the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. The two of them are followed by an artist, Hussein Madi, who contributed to three of the juries of the 1980s (SAs 12, 13, and 14). Madi was a graduate of ALBA and the Accademia di Belle Arti in Rome. Another artist follows with two jury participations that decade: Rafiq Sharaf (SAs 12 and 13). Sharaf was also an alumnus of ALBA as well as the Real Academia de Bellas Artes in Madrid, and was director of the Faculty of Fine Arts at the Lebanese University then. His participation was remarkable, as he was a vocal critic of the Sursock salons in the 1960s when he boycotted them. In the same two juries as Sharaf (SAs 12 and 13) was another figure associated with another Lebanese university: Reverend Father Abdo Badawi of the Holy Spirit University of Kaslik (USEK). Badawi was head of the Department of Conservation, Restoration, Cultural Property and Sacred Art there. Two other figures round up the two-timer jury list that decade, both of whom served on the same juries (SAs 11 and 14): Joseph Tarrab and Sylvia Agémian, whom we have introduced above.

None of the above can be considered amateurs in the field of visual arts. Khater specifically cites Aimée Kettaneh, Rickat Salam, Abdul-Rahman Labban, Samir Tabet, and Georges Tohmé in his criticism. Other than Labban, who had already served on two previous juries in the 1960s, and Samir Tabet, who participated in several salons as an artist and served on one further jury in 2008, the others served only on the jury of that 1982 tenth Salon d’Automne—the reopening of the museum during the war—along with Joseph Rabat who is not mentioned in Khater’s list. While Khater might consider them amateurs, it is notable that many were nonetheless active in the cultural field: Aimée Kettaneh, for instance, was the long-standing president of the Baalbeck International Festival committee. Their inclusion on the jury may reflect the museum’s urgent need to project cultural vitality at a precarious historical moment, even if that meant relying on figures whose primary expertise was not in visual arts criticism. Tarrab implied that the tenth Salon d’Automne was organized in haste, possibly to signal that “peace had returned.” The fact that most of these jury members only served once would suggest that the museum’s leadership itself recognized the provisional, improvised nature of this jury—prioritizing symbolic gestures of resilience over the rigour traditionally associated with its juries. In this light, the criticisms voiced by artists and critics alike reflect not simply personal grievances but a deeper unease about the fragility of cultural authority during a time of national crisis.

Ultimately, the Sursock Museum’s operations during the 1980s did not reflect a single coherent institutional stance toward Lebanon’s civil war, but rather a set of evolving responses to the fragmented and unstable conditions of the time. The article traced three overlapping tendencies: logistical and curatorial adaptations driven by wartime constraints (actual effect); expressed or implied institutional stances through patterns of inclusion/exclusion (disavowal); and the reactions of artists and critics (individual grievances). These are not presented as distinct phases or isolated positions, but as interrelated dynamics shaped by the war’s shifting material, spatial, and ideological pressures. At moments, the museum’s programming seems governed more by the logics of survival and pre-existing networks than by a desire to engage directly with the conflict. At others, curatorial choices—like the absence of war in exhibited works or the political valence of certain catalogue texts—implicitly echoed dominant narratives of blame, denial, or normalcy.

This complexity does not negate the war’s influence; rather, it demands an analysis that accommodates ambivalence. This article does not argue that inclusion and exclusion were exclusively determined by sectarian alignment or factional power, but rather that they were shaped by a convergence of wartime conditions, aesthetic preferences, institutional legacy, and the increasingly globalized art market. As Naef notes,63 the Arab art world in this period was grappling with imported market logics, formalist aesthetic legacies, and evolving regional debates on authenticity, representation, and modernity. The Sursock Museum reflected these entanglements—often passively, sometimes strategically—through the choices it made and the discourses it avoided.

In this light, the case of the Sursock Museum in the 1980s becomes less about identifying a singular political position and more about analysing how a cultural institution—one with claims of neutrality—became a site where aesthetics, institutional priorities, and wartime realities collided. Inclusion and exclusion were not simply reflections of political bias or aesthetic judgment, but also of deeper contradictions within the Lebanese art scene’s attempts to define itself amid national rupture and global transition.

This research was conducted in the context of the research project Lebanon’s Art World at Home and Abroad (LAWHA), which has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 850760).

Agémian, Sylvia. “Activités artistiques: Notes et Propositions sur les travaux susceptibles d’être menés au Musée Sursock en l’absence d’expositions.” Sursock Museum Archives, Beirut. 5 September 1979.

Agémian, Sylvia. “Travaux concernant la Bibliothèque du Musée.” Sursock Museum Archives, Beirut. 10 October 1979.

Agémian, Sylvia. “Xe Salon d’Automne 1982 Préparation.” Sursock Museum Archives, Beirut. 5 October 1982.

Agémian, Sylvia et al. Musée Nicolas Sursock: Le livre. Beirut: Sursock Museum, 2000.

Amhaz, Mahmoud. Al-fann al-tashkili al-muʿasir: At-taswir 1870–1970 [Contemporary fine art: Painting 1870–1970]. Beirut: Dar al-muthallath, 1978.

Dafoe, Taylor. “Will AI Change Art History Forever?” ARTnews, 30 August 2024. https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/ai-changing-art-history-raphael-painting-attribution-1234716025/.

Ghorayeb, Laure. “Aboussouan: La jawaʼiz bal shiraʼ ila an namluk majmouʻah laʼiqah” [Aboussouan: No prizes, only acquisitions, until we have a decent collection]. An-Nahar, 28 November 1974.

Kaïssi, Mohammed al-. “Risalah ila al-qayyimin ʿala mathaf sursuq” [A letter to the curators of the Sursock Museum]. Sursock Museum Archives, Beirut. 8 February 1989.

Khater, Nazih. “Mathaf Sursuq akthar min salah” [Sursock Museum is more than a hall]. An-Nahar, 29 September 1982.

Khater, Nazih. “Maʼrad al-Kharif shuhub am ʼafiyah?” [Fall exhibition paleness or wellness?]. An-Nahar, 24 December 1982.

Khoury, Jalal. “Je suis inculte!” [I am uncultivated!]. Magazine, 17 December 1964.

Maltzahn, Nadia von. “Guiding the Artist and the Public? The Salon d’Automne at Beirut’s Sursock Museum.” In The Art Salon in the Arab Region: The Politics of Taste Making, edited by Nadia von Maltzahn and Monique Bellan, 253–80. Beiruter Texte und Studien 132. Beirut: Orient-Institut Beirut, 2018.

Maltzahn, Nadia von. “The Museum as an Egalitarian Space?” Manazir Journal 1 (October 2019): 68–80. https://doi.org/10.36950/manazir.2019.1.1.5.

Mapping MENA. “Barbir Checkpoint.” Last accessed 24 July 2025. https://mappingmena.org/map/lebanon/barbir-checkpoint.

Maroun, Pierre. “Dossier: Amine Gemayel Former President of Lebanon.” Middle East Intelligence Bulletin 5, no. 2 (February 2003). Archived at the Internet Archive, last accessed 13 August 2025. https://web.archive.org/web/20030801140636/https://www.meforum.org/meib/articles/0302_ld.htm.

Melki, Loutfalla. “Nicolas Sursock: The Man and His Museum.” In Agémian et al., Le livre, 19–23.

Naef, Silvia. Bahthan ʿan Hadatha ʿArabiyya [In search of an Arab modernity]. Beirut: Agial Art Gallery, 1996. First published as À la recherche d’une modernité arabe. Geneva: Slatkine, 1996.

National Legislative Bodies / National Authorities. “Lebanon: National Reconciliation Accord – Taif Agreement (1989).” UNHCR Global Law and Policy Database (Refworld). 5 November 1989. https://www.refworld.org/legal/agreements/natlegbod/1989/en/121325.

Osman, Ashraf. “The Rise of the Sursock Museum: The Power of the Image to Create an Image of Power.” In A Driving Force: On the Rhetoric of Images and Power, edited by Angelica Bertoli et al., 287–304. Venice: Venice University Press, 2023. https://doi.org/10.30687/978-88-6969-771-5/017.

Rassi, George al-. Risha fi mahab al-rih: Antulujya al-fan al-tashkili al-lubnani min al-bidayat hatta al-yawm [A brush in the wind: Anthology of Lebanese fine art from the beginnings until today]. Beirut: Dar al-Hiwar al-Jadid, 2012.

Sissérian, Rosine Vartouhi (RoseVart). “‘Le Salon d’Automne’: What Are We Looking For?” Le Reveil, 25 January 1989. Reprinted in Sonia Nigolian, RoseVart… A Life Story, 16–18. Beirut: Photogravure Packlayan, 2000.

Smaira, Dima, and Roxane Cassehgari. “Failing to Deal with the Past: What Cost to Lebanon?” International Center for Transitional Justice. 30 January 2014. https://www.ictj.org/publication/failing-deal-past-what-cost-lebanon.

Sultan, Fayçal. Kitabat musta’adah min dhakirat funun Bayrut [Writings recovered from the memory of Beirut arts]. Beirut: Dar Al-Farabi, 2013.

Sultan, Fayçal. “Maʿarid al-Kharif fi Mathaf Sursuq 1961–1986” [Autumn exhibitions at Sursock Museum 1961–1986]. As-Safir, 29 January 1987.

Sursock Museum. “Beyond Ruptures, A Tentative Chronology: Curated by Karina El Helou.” 26 May 2023. https://sursock.museum/content/beyond-ruptures-tentative-chronology.

Sursock Museum. “Je suis inculte! The Salon d’Automne and the National Canon: Curated by Natasha Gasparian and Ziad Kiblawi.” 26 May 2023. https://sursock.museum/content/je-suis-inculte-salon-dautomne-and-national-canon.

Tarrab, Joseph. “Le Salon d’Automne au Musée Sursock: I-Une revanche posthume.” L’Orient-Le Jour, 21 December 1982.

Wehbe, Hiyam. “D. Amhaz.. rassaman wa bahithan: ‘Nawafidh al-dhakira’ jadidi alladhi ʿudtu bihi min al-harb” [Dr Amhaz, painter and researcher: ‘Windows of Memory,’ my latest that I brought back from the war]. Al-Liwaa, 31 December 1982.

Xe Salon d’Automne. Beirut: Sursock Museum, 1982. Catalogue of an exhibition held at the Sursock Museum, Beirut, 20 December 1982–20 January 1983.

XIIIe Salon d’Automne. Beirut: Sursock Museum, 1987. Catalogue of an exhibition held at the Sursock Museum, Beirut, December 1987–January 1988.