In this interview, Lebanese artist Greta Naufal (b. 1955) looks back at her beginnings as an artist during the 1980s, reflecting on her education and early exhibitions within the context of the ongoing war in Lebanon. Initially drawn to science, her passion for art had already taken root during her teenage years through painting workshops at ALBA, where she studied under Guvder. The practice of painting became an intuitive form of expression, later deepened by her engagement with theoretical texts and visits to museums in Europe. Despite societal and institutional challenges, she pursued Fine Arts at the Lebanese University’s Raouche campus, where she was mentored by prominent Lebanese artists such as Aref El Rayess, Yvette Achkar and Amine El Bacha. Naufal recalls both moments of inspiration and instances of gender discrimination. Her formative years were shaped by resilience, passion and a deep connection to painting. In 1985, the artist travelled to Paris to pursue a PhD at the Sorbonne under Marc Le Bot, with a research proposal on the impact of war on Lebanese artists. Despite her efforts, Le Bot never responded, and she returned to Beirut due to escalating violence. Over the following years, her art continued to respond to her lived experience, shaped by war. Exhibitions like The Way of the Cross (1986) and Nine Months (1987) focused on survival, maternity and loss. She was part of pivotal events like Beirut Tabaan (1989), which fostered cross-sectorial artistic collaboration. Her works evolved into installations and performances, such as the 1993 happening in a ruined cathedral. She sees herself as a link between generations, concerned by the erasure of artists who remained during the war, emphasizing the lasting relevance of resistance and time.

Painting, Lebanese Civil War, Maternity, Shelter, Goethe-Institut, War Generation

This interview was received on 9 June 2025 and published on 17 December 2025 as part of Manazir Journal vol. 7 (2025): “Defying the Violence: Lebanon’s Visual Arts in the 1980s” edited by Nadia von Maltzahn.

This interview is an edited version of a conversation with Greta Naufal in French on 23 May 2025 by Nadia von Maltzahn and Monique Bellan (on Zoom). It was edited and translated by Nadia von Maltzahn and reviewed by Greta Naufal.

Born in Beirut in 1955, Greta Naufal is a visual artist and art educator. Her work was featured in a number of exhibitions in the Arab World as well as overseas, and is part of various public and private collections including the Royal Museum of Stockholm, Millesgarden Museum, Sursock Museum, and the BeMA collection. Greta Naufal has also been teaching art in several educational institutions in Lebanon since 1983, mentoring many emerging artists. Often reflecting on the environment that surrounds her, Greta Naufal experiments with various media including painting, collage, drawing, photography, lithography, video, and installations. In 1982, after the Israeli invasion of Beirut, Greta Naufal produced a body of work on the theme of displacement and survival. This established her as an influential artist of the so-called “war generation” with a distinctive expressionist style. Throughout the 1990s, she became one of the first artists to document post-war Beirut by conducting extensive field research on the vanishing architectural heritage, its impact on collective memory, and the personal narratives of the inhabitants of the city. Whether through her interrogations of her fluctuating relationship with Beirut, her explorations of the human condition through portraits of great musicians and intellectuals, or her denunciations of violence in all its forms, Greta Naufal’s artworks remain strongly rooted in the contemporary space and time we live in.1

We would like to start in 1976, with your shift from studying Chemistry to Fine Arts at the Lebanese University. Can you tell us more about what motivated you to study Chemistry, and what then made you switch to Fine Arts?

Why did I choose to study Chemistry at first? You know how experimental we can get at such a young age! Actually, before starting my university degree at the Lebanese University, I was already very interested in art. I went to ALBA, the Académie Libanaise des Beaux-Arts, which at the time was in the area of Msaytbeh in Beirut. I was fifteen years old and keen to enrol in a painting workshop. My parents encouraged me because I always enjoyed drawing and the use of colours. I joined a class with Jean Guvderelian, more famously known as Guvder.2 He is no longer with us today. He was the first one to initiate me into painting. It was a great discovery for me because I was painting intuitively. I obviously did not have much technical know-how, nor an understanding of the process that governs the discipline of painting. Painting was a way of expressing myself, of responding to an urge for visual representation. When I started painting with Guvder, I realized that there was a whole new world opening up for me. Practice was essential, but there was also knowledge to be acquired from looking, reading, and researching. One has to instruct oneself through books and documentaries, by visiting museums and art galleries and so on. The experience of others is enriching and can be a great source of inspiration.

It must be said that, at the time, it was not easy to choose the path of art. Neither the country nor the society would support artists as we see happening a bit more today. Therefore, I needed to take care of myself. Maybe I could have started with physics or biology, but I went into chemistry. Science fascinated me in school. However, a year later, I decided to change and focus on Fine Arts because I saw that this is where my passion truly lies. Some books were formative for me during these early years, such as Pierre Pizon’s Le rationalisme dans la peinture (1978) [Rationalism in painting] or Xavier de Langlais La technique de la peinture à l’huile (1959) [The technique of oil painting].

And were these books available at the university?

No. I bought these books during my trip to France in 1979. I was in my third year of undergraduate studies and a visit to Italy was organized by the university. At that time, they had a budget for cultural trips. We travelled to Rome and Florence along with the students of architecture, accompanied by the art critic Faycal Sultan and others (fig. 1). I continued the journey to Paris on my own, impatient to visit the museums and acquire books on painting. I remember seeing an exhibition of Salvador Dali at the Centre Pompidou. The Musée de l’Homme had a profound impact on me as well.

Can you tell us more about the Lebanese University at that moment, and the Institute of Fine Arts (Branch 1 in Raouche)?

The Lebanese University was located in a building opposite the famous rocks of Raouche in Beirut, not far from Galerie Janine Rubeiz. The location was appealing because it overlooked the sea. I remember how the rooms were spacious, but we had no lockers! We needed to carry our heavy material back and forth every time we went to class. This was particularly challenging. The main advantage of the Institute of Fine Arts was that the most prominent figures of modern art in Lebanon were teaching there. We were very lucky because we could benefit from a pool of masters in the field.

Aref El Rayess was teaching us composition, Rafic Charaf landscape representation, Mounir Eido sculpture, Seta Manoukian and Amine El Bacha painting, Yvette Achkar drawing, and Jamil Molaeb printing. Aref El Rayess would lend his students his own printing machine since the university did not have any (fig. 2). He had already published his book on the drawings of the war3 using this same machine. He was a very generous artist, especially with his students, and we later became good friends. There was also Simone Baltaxé with whom I took one course of painting, and Nadia Saikali, who had just arrived from France. I also took one course with Hassan Jouni, another with Hussein Madi, and one more with Rashid Wehbe. This is to say that all these influential artists were collectively transforming this place into a laboratory of creative thinking and making.

I must admit that with some teachers, the chemistry immediately clicked. While with others, it did not. With Yvette Achkar, for example, it was very pleasant. There was a lot of encouragement; the relationship was equal. She lived near my house, so we went back home together sometimes and became friends later on. She had a beautiful way of teaching. She observed the whole process of our work, waited until the end, and when she felt that she could intervene as a teacher, she would do so with just one line. It was final. She was the one who put the finishing touch on our work.4 Amine El Bacha had a similar approach.

With Hussein Madi, however, it did not really click. There was also Moussa Tiba with whom it did not click at all. I remember how we had to submit a thesis during our last year. I and another student (who was absent for most of the year!) received the same grade of nineteen out of twenty. The jury suggested splitting the scholarship between the two of us. Tiba, who was a member of the jury, rejected this on the grounds that I was a woman, married, and going to have children which, in his opinion, meant that I did not need a scholarship. He was planning my future for me like a “bassara” (Arabic word for fortune teller).

I remember one more dramatic incident with my classmates during those years. I don’t know if I should mention it, but actually I want to. We were a small group of students at the time, seven in total, with five young men and two women. I don’t recall the name of the other woman, but she got harassed, which forced her to leave the university.

So I was the only woman in class. Out of the five men, two used to attend irregularly and I forgot their names. The other three were Hamada Zaiter, Abdallah Kahil, and Ali Chamseddine. Zaiter later took care of the collection of mosaics in the palace of Beiteddine, which he did with much devotion. Kahil went to New York on scholarship to study Islamic Art, and then came back to teach at the Lebanese American University (LAU) where we became colleagues. Chamseddine was a very particular young man, he had an interesting touch as an artist. His work was subtle. He was a shy person who did not speak much, yet everything was expressed through his work!

The Institute of Fine Arts of the Lebanese University was established in the mid-1960s in the Grand Serail building in Downtown Beirut. Following the outbreak of the war in 1975, it opened Branch 1 in Raouche, which you have described to us. It also set up a second branch in Furn al-Shebak in 1977, which moved to its current location in 1979. Did you have any relationship with Branch 2 at the time?

We were disconnected from the second branch; at that time everyone was in Raouche. All the artists teaching were there. We did not think much about the division between regions, but the war had divided the country and its people. At first, I did not believe in it much. I noted this division during the 1989 exhibition of Beirut Tabaan. The exhibition aimed to bring together the artists who were actively working during the war; however, the absence of the artists from East Beirut was obvious. They were participating, but they were not physically present. This division between East (sharqiyyeh) and West (gharbiyyeh) remained in people’s psyche. I will share an anecdote on the subject. In 1999, nearly a decade after the civil war had ended, I was collaborating on a book in tribute to Louise Wegmann,5 the founder of the Collège Protestant Français. I held the position of Professor of Visual Arts there since 1982, and was therefore invited to design the book. We were printing this book in a press located in the eastern part of the capital and I was having a conversation with the employees who kept asking me, “Are you really from West Beirut? Do you come here all the way from the West, what happens there? We will never go there.” Some people living in the eastern part of Beirut were afraid to come to the western side. We moved more easily in this part of the city. The country was politically and socially divided and continues to be.

In 1980 you completed your master’s degree in fine arts on the aesthetics of comics at the Lebanese University. What attracted you about the medium of comics?

When I started university in the early 1980s, I discovered the Art of Comics with a capital “A.” We were used to the French term “la bande dessinée.” It had been recognized as an artform since the 1960s, but we did not have access to such publications in our part of the world.

In Lebanon, comics were not appreciated as an art, they were associated with magazines for children. I started discovering the world of comics for adults with my husband back then who went on to specialize in it, setting up the first collective of comics artists in Lebanon and the region.6 One day, one of my teachers came back from Europe with a stack of art books including various comics albums. Those were not magazines but extraordinarily illustrated books. He proposed that I pursue my research on the subject as a way to introduce it to the local artists. I gladly accepted and he started sharing with me all the resources he had. I remember that the work of Spanish artist Esteban Maroto caught my attention in particular. His sense of composition, his cinematographic vision, his mastery of human anatomy, and the intense black and white scenes were captivating. I learned through him how some painters chose to shift to comics in order for their work to reach a wider audience.

Then why did you not continue in comics?

I didn’t even start there to continue! I have been drawing all my life and my drawings were used as illustrations in various publications. I have taught drawing classes for nearly four decades at the Lebanese American University (and other Lebanese universities as well), but I was and still am dedicated to painting primarily. My research as a student helped me clearly understand the role of painting, as it was being challenged by new forms of visual art.

I did video art and I continue to experiment with this medium because I love the spontaneous aspect of it. However, nothing compares to painting. It is of a completely different nature. It connects us to matter and the elements. It can be touched, it can be smelled, it is skin and surface. It is of the now, of the instant. Each stroke captures this essence. Painting captures the intensity of my experience best, it makes me sit with a subject in a completely new way. Occasionally, I have painted diptychs or triptychs, but in my painting, my intention is not to narrate a story, there is no sequence of imagery. Painting is the story. I could express it this way: in my experience, painting is the translation of the consciousness of our existence.

In May 1982 you held your first solo exhibition, at the Goethe-Institut in Manara, entitled Beyrouth Ma Ville. What did you exhibit there?

Beyrouth Ma Ville was an important milestone for me (fig. 3). It was my very first solo exhibition at a time when I witnessed many people leaving the country. The city felt empty. Those who could leave during the war did not hesitate. I wanted to mark my presence, my belonging to this city. When we had an hour of calm, especially in the afternoon, we would walk near the Corniche—Beirut’s seaside. I would take photographs and paint people there (fig. 4). The exhibition was about a sense of place, the city and the sea, the horizon. It was an escape. This is what I aimed to depict. I also painted portraits of people from the city because when you paint a face, you feel a presence, everything is there. Everything is written on this person’s face, everything they feel. Eye contact is paramount for me. It connects us.

Can you tell us more about how this exhibition came about, and the role of the Goethe-Institut at the time?

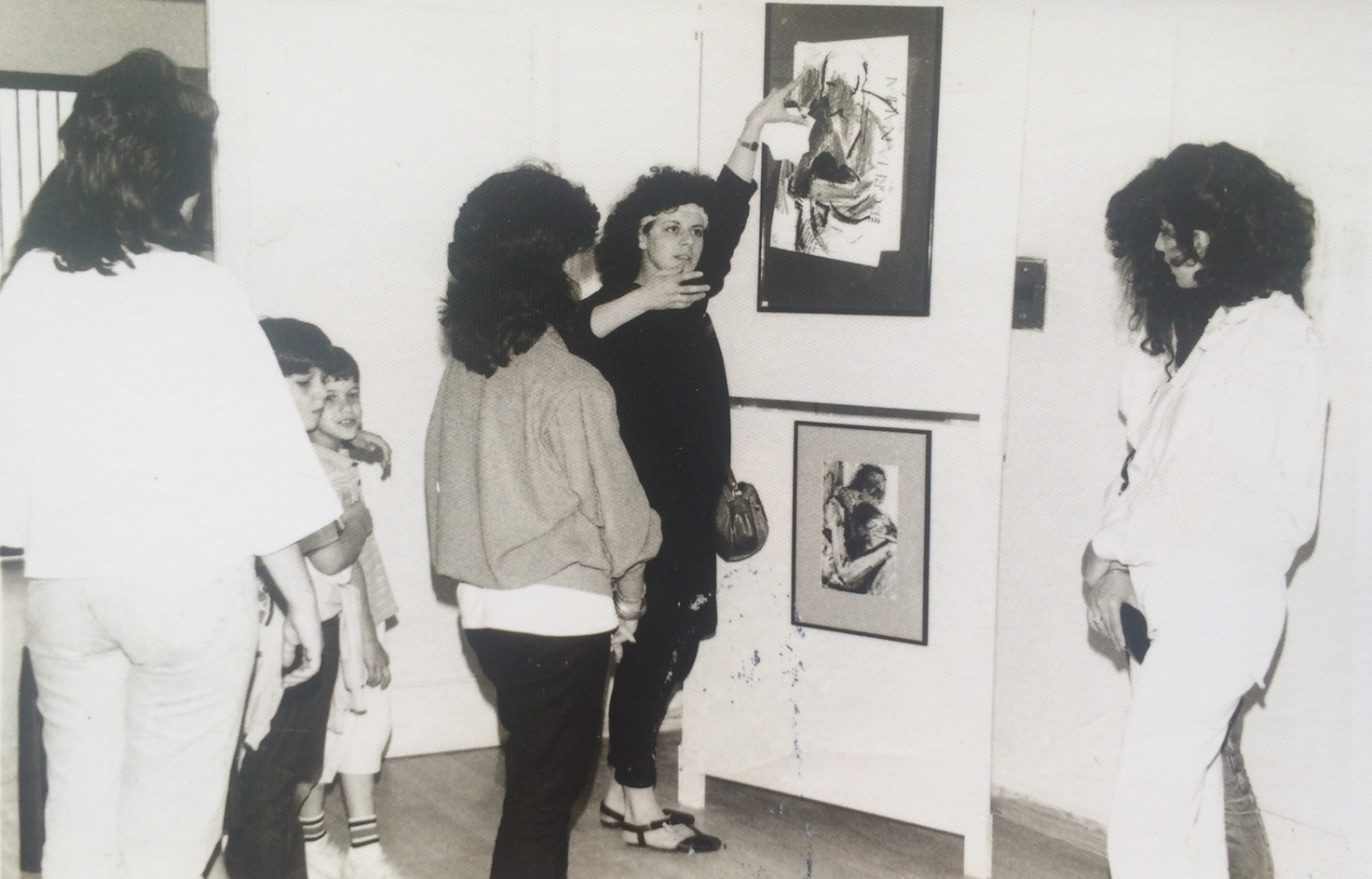

I came to the Goethe-Institut thanks to my friend Barbara Kassir who was the head librarian there at the time (fig. 5). First, she suggested that I use one of the rooms as a studio. Then, she offered to display my work in their exhibition space.

In 1982, we had a shortage of water and electricity. It was a time of war; there were bombshells on a daily basis. I had my first child that year and I needed a safe place to work. Barbara suggested to me to transform one of the rooms into an atelier for painting. Two artists had already worked there; a Palestinian and a Lebanese. The first was Nasser Soumi and the second was Paul Wakim. There was a printing machine and a large water tank where I could wash my painting material. It was an informal space, open and full of light. I found it conducive to work there. I could go down to the library as well as communicate with the various visitors and students of the German cultural centre. Sometimes they screened films. The institute was active during those days. It was a dynamic and vibrant place.

How did you perceive the art scene at the time?

It must be said that in 1982, the newly elected president Bashir Gemayel was assassinated. This was followed by the massacres in the two Palestinian camps of Sabra and Shatila. The political scene dimmed the light of any other scene. The silence that reigned over the city was really indescribable. It was frightening. It felt as if this city was swallowed by the inside of the earth.

You are asking about the art scene… At that time, I only remember attending an exhibition by Mona Saudi at Galerie Épreuve d’Artiste. There was the Salon d’Automne at the Sursock Museum that year too. I don’t think I went there. And then there were all these political events. I took my daughter and left the city to spend some time in the mountains. I remember that there was an exhibition by Naziha Knio in the Shouf. I couldn’t see it. I did not move. There was also Lulu Baassiri at the Smugglers’ Inn in Hamra. There were sculptures that Alfred Basbous exhibited at Gallery One in Zalka. I did not go [to that] either. I did not want to move. And then there was Zaven Khedechian in Kaslik. It was out of the question that I move. I did not want to be traumatized further by the snipers or the bombshells.

Were there still activities, or possibilities, to exhibit in Hamra? You know the Muntada, for example. Did you sometimes go to see exhibitions there?

Yes, I went to the Muntada. I remember attending an exhibition of Amine El Bacha there.

It was also a meeting place, where there were other events.

Yes, but at the time, we mainly met in the cafés on Hamra street, especially the HorseShoe café. Sitting in open air was important, we avoided closed spaces. I would meet the writer Rachid Daif, the artist Rafic Charaf, and the art critic Nazih Khater among many other intellectuals and artists. Hamra was really the heart of the city at that time.

You exhibited at the Galerie Chahine in the Solemar Beach Resort in 1984. Many exhibitions took place in the coastal area north of Beirut at the time. Did exhibiting there feel different, or was the public similar to that in Beirut?

Richard Chahine had two galleries, one in Beirut and another in Jounieh. I was not very much connected to the scene outside of the capital at this point, so he invited me to exhibit in Jounieh for the first time. I had other exhibitions in later years outside of Beirut but in those years, it was very important for me to exhibit in the heart of the city which inspired all of my work. In 1984, Chahine was keen to have my work in Jounieh where he had invited a minister. The most interesting encounter I had during this exhibition, however, was with a poetess whose name was Nohad Salameh.7 The conversations with her were very engaging. This exhibition was dedicated to the Nuba community in Kau; much was written about it in the newspapers of the time. More than where I exhibited and the audience, I could tell you about the work itself. I was a mother of two daughters by then and I became increasingly more interested in ancient social structures. I was inspired by the photographs of the Nuba by the German film director Leni Riefenstahl and decided to draw and paint them. I was experimenting with various media, oil, acrylic, ink, and watercolour (fig. 6 and fig. 7).

In 1985 you travelled to Paris to enrol at the Sorbonne University as a PhD candidate under the supervision of Marc Le Bot. Tell us more about what came of this.

I left for Paris with my project proposal. The topic I wished to write about was the scars of war on Lebanese artists. I had a list of artists in mind starting with Seta Manoukian. She had left Lebanon in 1985 after two exhibitions (in 1979 and 1984). I was fond of the work she had done with children as well and which she had published in books. Next on the list was Imad Issa. He had travelled to Spain, then came back during the war. He started sculpting once back. I liked his sculptures using cement. His approach was unique and avant-garde. He produced this work in his village in the south of Lebanon, away from the city, where he stacked blocks on top of each other with iron rods inside them. I found this work extraordinary. Then, I also had in mind Mohammad Rawas because I had seen his exhibition at Galerie Rencontre in 1979. Rawas had sent work from London, where he was doing his studies before coming back to Lebanon.

Today, I would probably add to this list Hamada Zaiter, who used to be my classmate and who had taken up the restoration of Byzantine mosaics during the war. Another artist who did very interesting work during the war was Aram Jughian. He was the first to do a “happening” in Lebanon. At some point, he had to leave his house and came up with the genius idea of using the Salon d’Automne at the Sursock Museum as his shelter. He brought his carpet and slept in the museum! This act was very bold and impactful. Many people found it distasteful because they probably resisted contact with homeless people in the streets. For me, he was an artist in the true sense of the word. His intention was to trigger our reflection on the conditions artists live in. Provocation in art can be on point. He was inviting everyone to think about those who are producing the work which we see, devoid of context, in the space of a museum. I started appreciating his work since he did an intervention in Amal Traboulsi’s Galerie Épreuve d’Artiste. Aram was one of the few artists who travelled back and forth between East and West Beirut, accompanied by his dog. He came to the art gallery with two kilos of bananas during an exhibition—I forgot which artist was exhibiting at the time. He scanned the exhibition, then started speaking about the business of galleries and did a spontaneous public performance where he started to eat bananas in the middle of the space. Amal Traboulsi was shocked. I loved it! I also agreed with him about the fact that galleries in time of war cannot continue their business as usual. In fact, I would find it more considerate that galleries close rather than show art which does not denounce the atrocities of war. I think that today with all that is going on, art shows in galleries tend to make my heart ache. There is a famine just a few kilometres from us. I thought a lot about what to do. We have to be aware of what’s going on in the world. It can’t go on as if nothing is happening. This really upsets me.

Anyway, I have digressed! Back to my research proposal. The last person on my list would be Fadi Barrage. His studio in the city centre was pillaged while he was in Greece. Galerie Rencontre saved parts of his work and exhibited it. It was very interesting because it was a quest. I will not say more because you have to get curious enough to find out for yourself!8

So I had prepared a draft paper, but Marc Le Bot did not answer. I paid for the trip to France during this black moment of Lebanon’s history, but he was away and unreachable. I waited a week for him to come back. He did not come back. I left my paper and wrote a letter. He never answered. I knew that I had to go back to Beirut because the situation back home was getting worse. This was in 1985.

In your 1986 exhibition, The Way of the Cross, which was again held at the Goethe-Institut in Beirut, you focused on the themes of survivors of war and maternity. Can you tell us more about the title and subject of the exhibition? Also, who was the public, and how did they receive your works?

It had been almost ten years since the civil war had started. It was not stopping. It was like a haemorrhage! Something had to end; I stopped painting with colour. I used black and white ink and felt the urge to draw the image of survivors of war (fig. 8). I also did a few pieces using the grattage (scratching) technique, where layers of coloured pastel were covered with black ink. I could not help but keep alive the faint hope that the war would stop. At the same time, I felt like it would never stop. I had to live with it. It’s like when you live with a bacterium in your body. I had hope left, though. It wasn’t all black. There was always white and a sense of light in each artwork. I remember when a collector by the name of Ramzi Saidi came to this exhibition. This was the first time he visited the Goethe-Institut and the first time we were introduced. After a quick tour, he comes to me and tells me: “I will take one of them.” He started negotiating the artwork’s value. So I said to him: “If you want us to continue to live, if you really care for artists to continue to exhibit in this city, you have to accept.” He accepted and I asked him: “So which one did you choose?” He had chosen an ink drawing of a father and a child—“Paternity.”

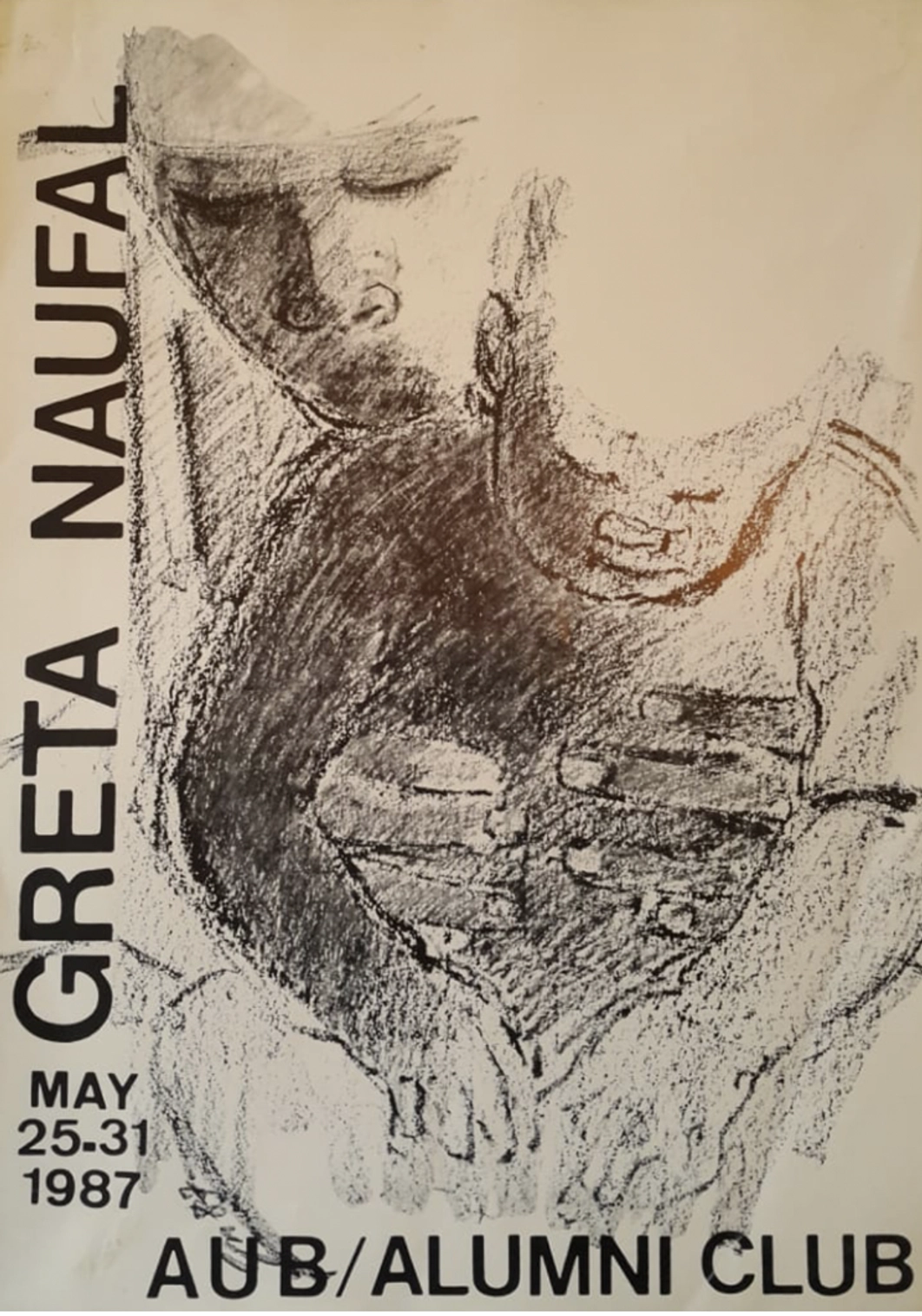

In 1987, you elaborated on the subject of maternity in your exhibition Nine Months at the Alumni Centre of the American University of Beirut (AUB) (fig. 9 and fig. 10).

The central theme of this body of work was maternity too. I was invited to teach a drawing class at the American University of Beirut which had an Alumni Centre. The subject of “mother and child” is central to the history of art as we all know, and I was pregnant again during this year. There is a reference in this work to what I saw when I was young, because I was in a religious school in Achrafieh. It was an Orthodox school where we had to attend mass every morning. There were extraordinary icons in the school’s church. It was full of icons of the Virgin Mary with the child Christ. That is something which stayed with me—there is always an unconscious side to our work which surfaces at times. I did not really pray with words; my prayer was looking at these icons. It was a very beautiful collection.

In the late 1980s you met Janine Rubeiz and took part in her collective exhibition Beirut Tabaan in 1989. How do you remember this exhibition? What did it mean to come together for an exhibition at that moment?

Janine Rubeiz was a very energetic woman. She worked a lot with artists and encouraged them to continue their art no matter what. We always saw her with paintings in her arms. She was aware that artists needed to continue producing, and that support was essential for them to continue. She was right. She fought a lot. She had learned that we were a group at the time including the owner of Galerie Rencontre, Antoine Fani, Imad Issa, Barbara Kassir and her husband Majid Kassir (who was working with the German television channel WDR and documenting on his camera the work of artists at the time). Janine Rubeiz came to us and told us: “I will bring the artworks and you take care of the rest.” And that’s what happened. The exhibition was conceived in an innovative way. Artworks were not just hanging on the walls, they were suspended from the ceiling, there was a whole scenography designed by George Khoury. There was also a large screen showing the writer Elias Khoury doing an interview about Beirut. Most of the active artists at the time participated in this collective endeavour, which acted as a bridge between the eastern and western parts of the city, between artists from various fields and different generations. Amine El Bacha and Rafic Charaf did not participate, but Aref El Rayess and Yvette Achkar did. I met Farid Mansour for the first time. The event connected us to writers and poets and fostered the meeting of visual arts, literature and crafts. I met the painter and ceramist Samir Muller then. It also included the work of illustration artists who had created comics about the war. There are exhibitions that we really have to talk about, and this is one of them.9

Beirut Tabaan took place during the same period of the “War of Liberation” (March 1989–October 1990), when you ended up spending a month in the shelter of your building in the Watwat area in Beirut. Did the exhibition take place at a moment of calm? Was it in between?

Beirut is full of contradictions and opposites coexist at all times. Calm. War. Tension. There is always tension somewhere. It doesn’t stop. It is like a box of wonders. It’s a city that can surprise you any minute. Maybe that’s why people like Beirut in spite of it all, it’s never boring. There is always something to keep you on your toes.

Al Jazeera did a documentary about artists during the war where I talk about my experience in the shelter. The recordings give a first-hand account of this period.10 In 1989, I discovered the films of Pina Bausch at the Goethe-Institut; Barbara had requested them from Germany. I really wanted to see Café Müller.11 I watched it a dozen times. It spoke to me a lot, and even to my children. It must have resonated with us because we had to go down to the shelter almost every afternoon during this period, and everyone had to carry their own chair, and there was this repetitive action of going up and down and movement of running back and forth. Every afternoon, around 4 pm, the shooting would start. Bombs were dropped from the east onto the western region. They came from everywhere. Even in the shelter, we weren’t safe. Some people died in their shelters. I had a small sketchbook with me that I filled with sketches of people who were coming into the shelters whenever it was possible to sit and draw.

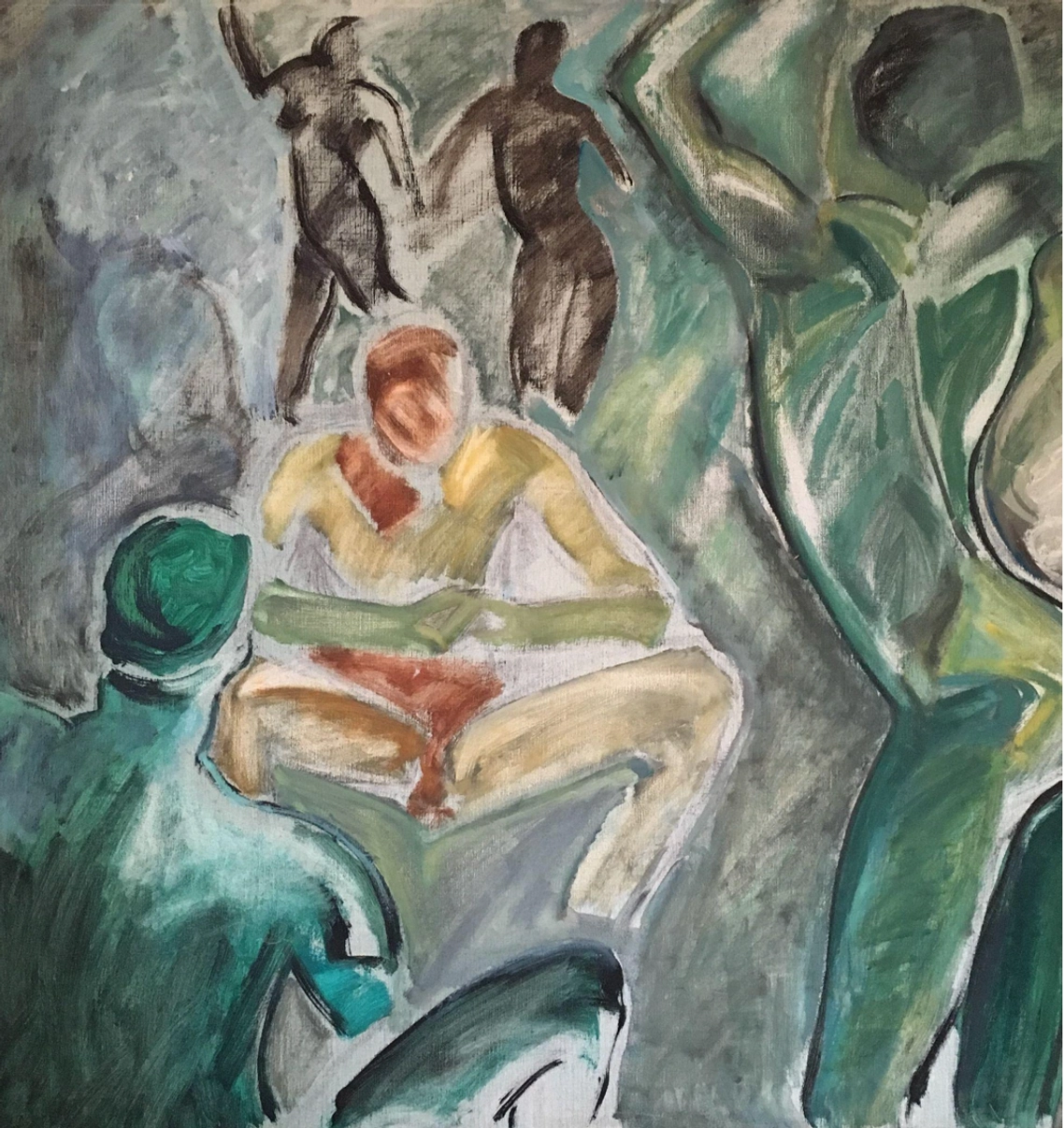

This was the only underground shelter in our neighbourhood. It was there because the basement of our building had an Armenian printing house. It had several rooms. The first time I went down there it was like going down to hell, I will never forget. It was in my building, but no one had gone down there before. During the earlier years of war, we would not need to go down to the shelter. This year, however, we had to. I had to do it for the children. I had three of them. The balcony of my house was hit by a bombshell one day, so I had no choice. For a month, every day, we had to rush down to the shelter. The people in the neighbourhood started to leave Beirut. In the end, there were only very few families left. We couldn’t sleep at night. We had to stay awake because we didn’t know what was going to happen. We didn’t know where the bombs were going to fall. We had to stay alert and listen to the news on the radio. People were going down to the shelter with the radio. They had little transistors. One night, the inhabitants of the third floor, who were Greek and usually did not come, came down as the bombing was too intense. They had the biggest tape recorder among us. I went up very quickly and fetched a tape of Greek music from my apartment, and we spent the night dancing to ease fear and distract our children. It was an extraordinary night. It was after this night that I would start painting on a large roll of paper the work inspired by Pina Bausch (fig. 11). There are Greek inscriptions on this painting which was done as a mural. I asked my neighbours about the Greek words for shelter and bombshells and inscribed them on this piece.

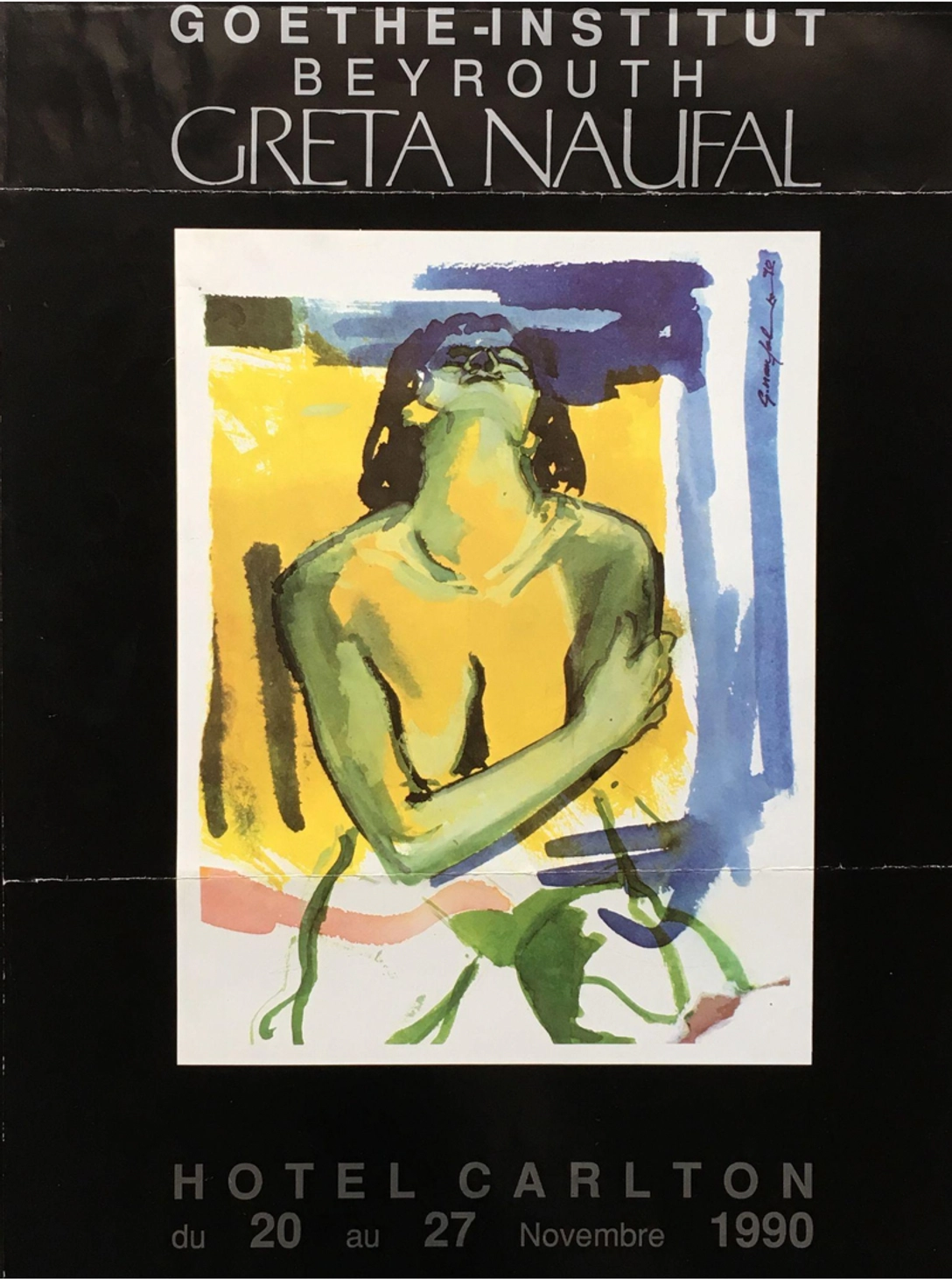

So this tribute to Pina Bausch was then exhibited at the exhibition Behind the Wall at the Carlton Hotel, organized by the Goethe-Institut just after the Taef Agreement. What did the title signify?

This three-metre roll (fig. 12) was exhibited for the first time at Carlton Hotel in 1990. I worked a lot during this period. Barbara Kassir suggested that the Goethe-Institut sponsors an exhibition at the Carlton Hotel in Raouche. And that is how it came to be (fig. 13). This event was a culmination of the extensive body of work I had produced during the last couple of years before the war ended. I decided to call it Behind the Wall because this is where we had to live when there was bombing. This became the title of a piece with a woman standing and screaming. I did lithographic prints of this piece because I did not want it to be confined to one house and several people who attended the exhibition requested it. Later, I used these prints to develop a series of works, each overlapping with other drawings or paintings (fig. 14). We compiled them in a book of poems by Marie-France Naufal.

Were you generally following artistic trends elsewhere at the time?

At the Goethe-Institut, I immersed myself in the world of Käthe Kollwitz, Pina Bausch, Joseph Beuys, Carl Orff, Werner Herzog, and many others. Otherwise it was through art magazines. There was an Iraqi review, al-Funun al-tashkiliya (Plastic Arts), and another one published here, Afkar (Thoughts). At the Collège Protestant Français, we had a good library with books and magazines regularly being shipped from France.

Can you tell us more about the happening you and Imad Issa did in the abandoned cathedral in Downtown Beirut in 1993, and what motivated you?

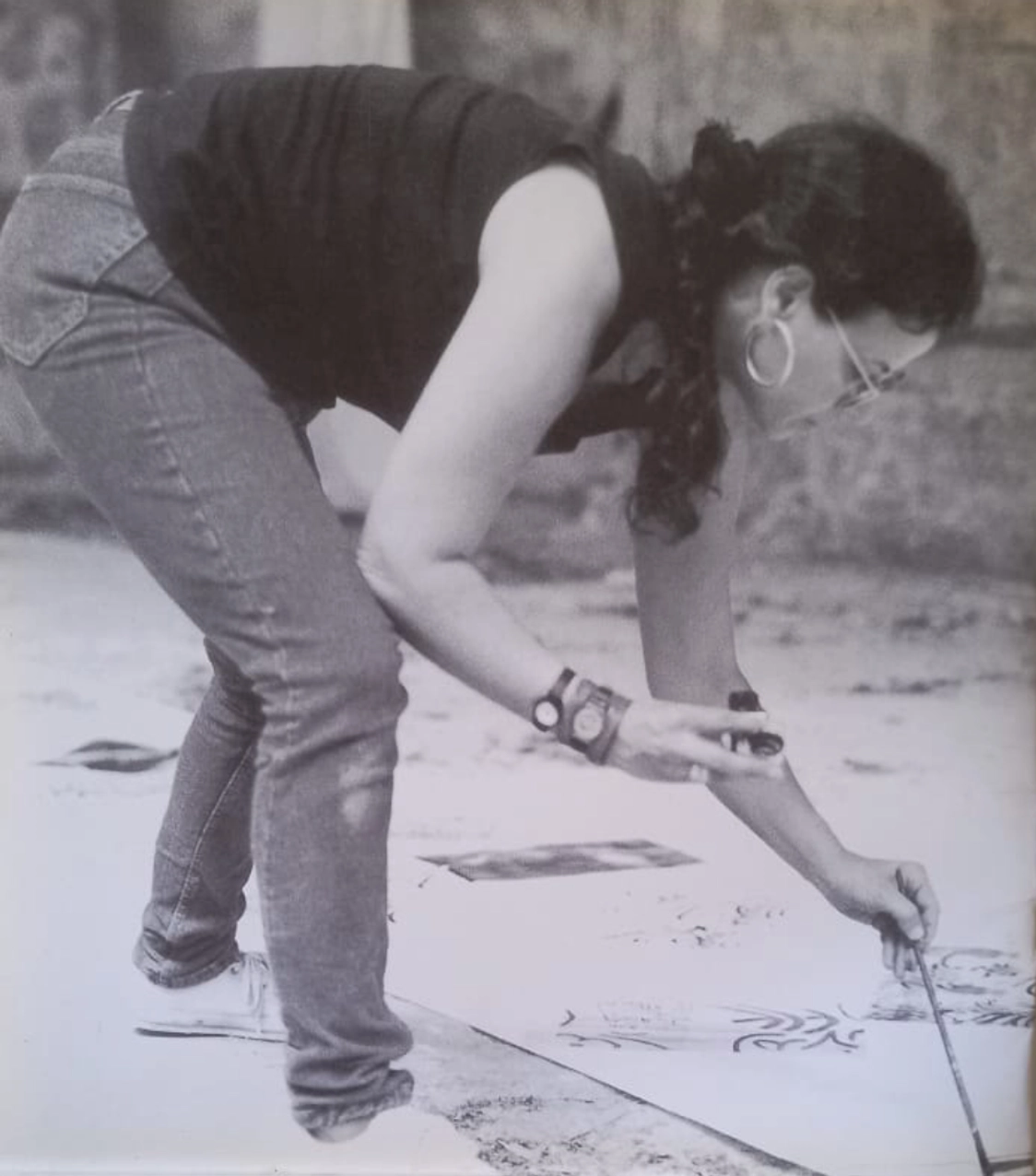

How can I express this—I could not see myself in 1993. I had started to get a sense of “the end of painting” in a way. I was processing many things within myself. The happening of 1993 was the first of its kind in Lebanon. I felt the need to be in an open space after experiencing the underground shelter. I did not see myself doing anything in a gallery, I wanted an open space that belonged to this city in ruin. There was a cathedral with a long history that had been looted and destroyed. I was there, taking pictures (fig. 15).

This cathedral had extraordinary stained-glass windows, but there was nothing left but rubble. The space was destroyed, without a roof, left open to the sky. I remember thinking that it felt more real, in direct connection with the sky. Then there were all these empty niches from where icons were stolen. The ground floor had broken slabs that had survived. There is always something that resists. Many things were stolen but they couldn’t take everything away. Again, there were things that resisted and survived.

The second floor was destroyed, but it had a ramp which I used to hang large paper rolls I had written and drawn on. In the evening, there was a little breeze, and they started to float. The candles were Barbara’s idea, we lit them together at night. I did mural collages, with the word hayat (life), and these seven hanging banners which spoke about time. During this period, all my work was done on paper, metres upon metres of paper rolls unfolding (fig. 16). They became a metaphor for the passage of time. The continuous wars that do not stop. Here I was, I will not stop either. My art will not stop to speak about life.

I did a brief performance as well, I opened my arms and stood there at the altar, to the side where there was a statue of the Virgin Mary (fig. 17). Majid Kassir filmed both artist Imad Issa and myself during this happening. Artists in Ruins was the title of the documentary for the WDR television channel. You know, there is always a gaze that dominates and threatens but we always find a way to escape it. This is why I always made sure to document with photography and keep evidence.

Do you think there was a divide between artistic practices before, during, and after the war, and consequently a generational gap? If so, how would you explain this? Do you consider yourself part of a generation of artists in Lebanon?

I’m going to try to position myself. I can’t say that I belong to the generation of artists before the war such as those modern artists who taught at the Lebanese University. I can’t say that I belong to the movement of conceptual artists who came after the war either. I am somehow positioned in the middle; I could be the link. That’s why I said before that, for me, it felt that the end of the war brought with it the end of an era for painting. It was not the end of painting but the end of a certain way of tackling painting.

I can’t place myself among the modern painters of Lebanon because I didn’t just paint (fig. 18). I have worked on several installations (fig. 19).12 I did video art13 and I have conceived a few short films.14 It was a need I personally had. I integrated video into some of my installations. So, I was not only painting. This is not to belittle painting; on the contrary, I had to experiment with other media to see how this would bring me closer to painting again, and how it would bring freedom back to painting. When I say painting, it is in the complete sense of what this word means. It is not just about taking colours and expressing yourself. I see what some people are doing today, but they did not “study” painting—not just what it is but what it does to you as a human being. And by study, I do not just mean learning a technique but experiencing a process that requires one’s full involvement. I am talking about painting in the real sense. Painting is not necessarily the act of painting, there is much more to it than the act. You have to study life in a way in order to do good painting. Modern artists have studied, they painted all their life. That’s what I mean.

Could we say that this alienation comes from the new generation who had studied abroad and who were not in Lebanon?

Those who were in the United States or in Europe started coming back to Lebanon and marginalizing those who were here, those who remained here. Some even went to the extent of making a tabula rasa of what preceded them, just like the war did. It felt at times as though we had never existed. They did not want to make the link. All of a sudden, they considered that art, what started to be labelled as “contemporary art,” was born in Lebanon with them.

This was simply not true. We cannot ignore the people who were there and who worked. We cannot say that installations started with the young generation of postwar artists, many had done it before them but there was lack of awareness and lack of documentation and visibility.

Today, everything is shared on social media. This was a time when we did not even have mobile phones. When I do an exhibition, hardly any young artists come. Why? I go to all the significant exhibitions. I am interested in everything that is happening in my city and my country. The new generation lacks curiosity, I thrived all my life to engage my students and nurture their sense of curiosity.

I say to myself that everything happens in due time. Nothing disappears in this life. Everything comes in its own time. It’s much more important when something happens in due time. It has more impact. Maybe things take more time because of the situation in Lebanon and everything that is happening in the region, where the geopolitics are very complex. Much effort is required to assimilate all that has passed but time is our friend. I have a friend named time. I really believe in it. I have faith. I am not afraid of anything. Because there is faith in humanity. There is faith in time.