In December 1986, Kufa Gallery opened in London’s Westbourne Grove. After exhibitions of Old Maps of the Arab and Islamic World (3–30 June 1987), three Europe-based Kurdish artists Walid Mustafa, Tahir Hamid and Karim Azad (15 July–8 August 1987), and an exhibition in memory of the Palestinian cartoonist Naji al Ali shortly after his assassination in London on 29 August 1987 (29 October–4 November 1987), Rose Issa dedicated an exhibition to Contemporary Lebanese Artists (15 January–24 February 1988). This exhibition took place during a period of war in Lebanon and in parallel with preparations for the landmark exhibition that was to take place at the Barbican Centre the following year, Lebanon—The Artist’s View (15 April–4 June 1989). Contemporary Lebanese Artists not only aimed to raise awareness about Lebanon’s artists and the country’s plight, but also to raise funds both for the artists and for the Lebanese Red Cross, which received part of the gallery’s commission. In this roundtable discussion, the main protagonists behind Contemporary Lebanese Artists, gallerist Rose Issa and artist Mohammad El Rawas, discuss the creation and reception of the exhibition.

Rose Issa, Mohammed El Rawas, Kufa Gallery, London, Contemporary Lebanese Artists

This roundtable was received on 23 June 2025 and published on 17 December 2025 as part of Manazir Journal vol. 7 (2025): “Defying the Violence: Lebanon’s Visual Arts in the 1980s” edited by Nadia von Maltzahn.

This is an edited version of a roundtable discussion with gallerist Rose Issa and artist Mohammad El Rawas that took place at the Orient-Institut Beirut on Friday, 10 May 2024, in the presence of gallerists Nadine Begdache and Saleh Barakat and scholars Ashraf Osman and Nadia von Maltzahn.

Participating artists (fig. 1): Shafic Abboud, Samir Abi Rached, Yvette Achkar, Maliheh Afnan, Ida Alamuddin, Rima Amyuni, Ginane Bacho, Fadi Barrage, Henrig Bedrossian, Ali Chams, Saliba Douaihy, Fatima El Hajj, Mohammad El Rawas, Paul Guiragossian, Hassan Jouni, Halim Jurdak, Samia Osseiran Junblat, Sumayyah Samaha, Moussa Tiba, and—not included in the printed catalogue1—Suheil Suleiman, Willy Aractingi, and Imad Abou Ajram.

Rose Issa: I was telling Nadia that this exhibition in London happened thanks to you, Mohammad. Because you were the organizer, the curator, the publisher, everything was on you. I did not do anything.

Mohammad El Rawas: You were the director of the gallery.

Rose: Yes. And I collected Ida Alamuddin because she was in London, and I went to Paris and collected works from Shafic Abboud.

Mohammad: You see, these are the missing points, because I was wondering, how did I manage to collect all these works?

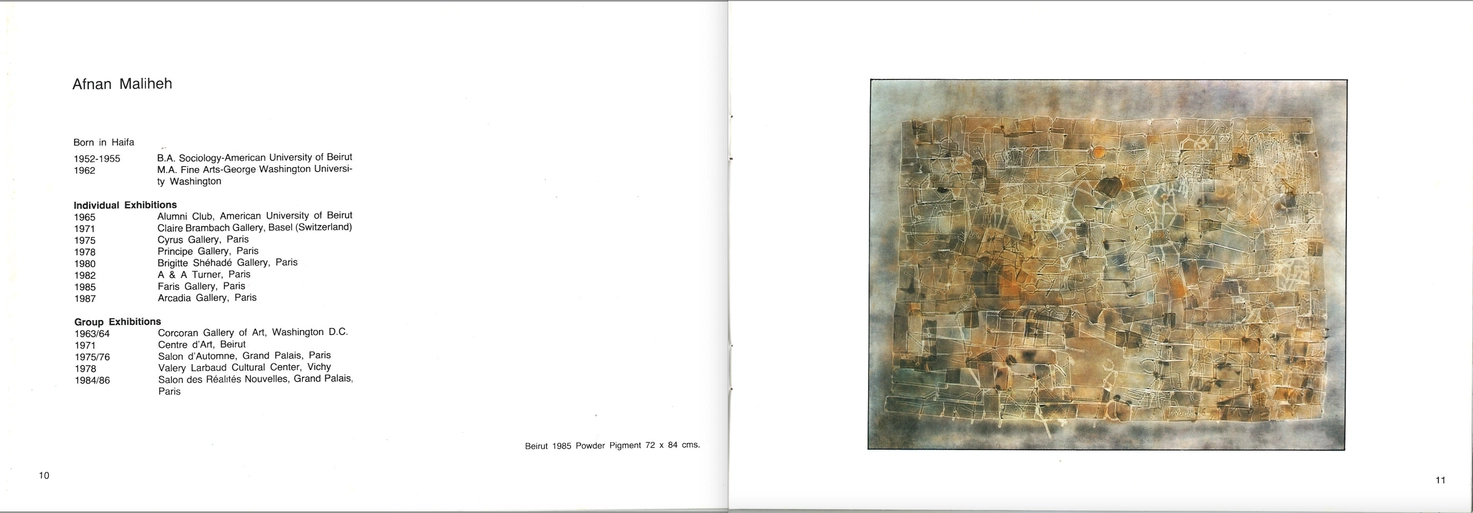

Rose: I went to Paris to see Shafic Abboud in his studio, to collect works from him. He told me, you are half Iranian, you should meet my friend who is also half Iranian. And he introduced me to Maliheh Afnan, who was not Lebanese but had lived in Lebanon for years. So we included her. I loved her very much.

Nadia von Maltzahn: Let us start at the beginning. What was the idea behind the exhibition?

Rose: It started by talking. Mohammad was in London six months before the exhibition. Next to Kufa Gallery was Saqi Books, and he was friends with its founder André Gaspard.2 There was war in Lebanon. And we did not know what to do to support the Lebanese. We said, the only thing we can do is to present some art and culture. We were talking and said, why don’t we do an exhibition in the middle of the war? The war was getting worse and worse. We thought maybe it would stop. But it never stopped. And Mohammad said, “You know, we can do that. I can collect many of the artists.” I did not know them personally. Because when I left Lebanon in 1977, I left as a mathematician, as a historian, as a journalist, not as a gallery owner. I started looking for support. I approached the British Lebanese Association, but they did not help at all. That was strange, as they were rather rich people of London. I asked to use their mailing list to mobilize and bring people. Myrna Bustani came and asked me who my father was. I said, “I’m not selling my father, I’m selling artworks.”

Mohammad: But, Rose, you managed to get all these sponsors at the end, which is quite a significant achievement!3 When I came back to Beirut after having talked to Rose about this project, I started collecting artworks. What I believe did help was that I held the position of secretary-general of the Lebanese Artists Association, a post which I held between 1983 and 1992. Hussein Madi was the president, Moussa Tiba was there, and myself. As a new committee, we had started in 1983. You know, there were no telephones. We used to hold the apparatus, hoping that it would get a line. It was so difficult. Until now, I am astonished. How did I manage to bring the works? I had a little flat in Clemenceau. It was occupied by the Amal Movement and I was kicked out. A friend of mine, an architect, wanted to migrate to the United States. He told me, “Please stay in my house.” Because he was afraid that somebody would occupy it. I told him, “What perfect timing.” So I had this place and started accumulating the works there. But how did I manage to contact the artists and pick up all these works? I don’t have a clue.

Nadia: Did you know all of them?

Mohammad: Of course. The only ones I did not know, and who I was happy to meet, were Ida Alamuddin and Maliheh Afnan. Because they were in London. And apparently the catalogue was printed missing three more participants.

Nadia: Yes, Suheil Suleiman, Willy Aractingi, and Imad Abou Ajram. In one of the exhibition reviews it said there was a separate side exhibition in the studio of Suheil Suleiman.

Rose: Yes. Suheil Suleiman was in it also. Because he lived in London.

Mohammad: I actually kept a few press cuts. This is al-Hawadith (29 January 1988). This is al-Majalla (January 1988). This is al-Qabas al-Dawli (8 March 1988). And this is al-Dustour (25 January 1988) (fig. 2).4

Rose: It was a great moment in London, because all the press moved from Beirut and elsewhere to London. London became truly an Arab capital. The magazines were working. Whatever you did, everybody covered it.5 It was a very buzzing time for the Arab press to be in London. Everybody who could no longer work elsewhere came to London or Paris, and mostly to London.

Mohammad: I remember two anecdotes that happened while we collected the works and contacted artists. The first person I thought of was Hussein Madi. I was seeing him almost every day. He told me, “Who are these artists? How do you want me to show with these? What are the criteria? With all my due respect to you, Kufa Gallery, André and Rose, I don’t want to be part of this.”

Nadia: What did he object to?

Mohammad: He objected because he thought that he was of a higher calibre. The other artists were not up to his level. He was not humble enough to show with them.

Rose: And they were more important than him.

Mohammad: Well, some. At least as important. The other person, funnily enough, was Nadia Saikali. Some of the artists had been my teachers at the Lebanese University. I called her in Paris—don’t ask me how I found her number—saying, “This is Mohammad Rawas. We are organizing an exhibition at Kufa Gallery in London. The director is Rose Issa. It is next to Saqi Books London.” And she said, “Who is that?” I said, “Mohammad Rawas, I used to be your student.” She said, “I’m sorry, I don’t recall you.” I said, “I was with Maroun Hakim, Christian Boussière, Imad Abou Ajram.” She said, “Oh, maybe. Why are you contacting me?” And then she said, and it really hurt me a lot, that “Listen, I am now in Paris, married to a French person, and have nothing to do with Lebanon. So, please, don’t call me anymore. I don’t want to be part of this.” It was heart-breaking to me. And that’s why she was not in the exhibition.

Rose: Very few Lebanese came and bought works at the exhibition, the ones who bought were Palestinian women, or British. They were not Lebanese. I was very shocked.

Nadine Begdache: Don’t be shocked. When we were opening galleries, since Dar El Fan, the Lebanese did not buy Lebanese artists. It started later. They buy as an investment now, to sell in auctions later.

Saleh Barakat: And don’t forget, in this period, in 1987, 1988, 1989, or we can say starting in 1983, Lebanon was really in a dire condition. Far worse than now. There was this crazy inflation. And then the crazy General Aoun. And a lot of people travelled. Many were living abroad during this period. Particularly from 1986 to 1989. I think you definitely inspired something with this exhibition, it was important to hold it.

Rose: I don’t know if we inspired anything. I felt like this was a necessity. When I saw you, Mohammad, six months before the exhibition, we talked and I was like, “Let’s do something for Lebanon that has a positive image, and maybe we can give some money.” Because truly, the works were so cheap.

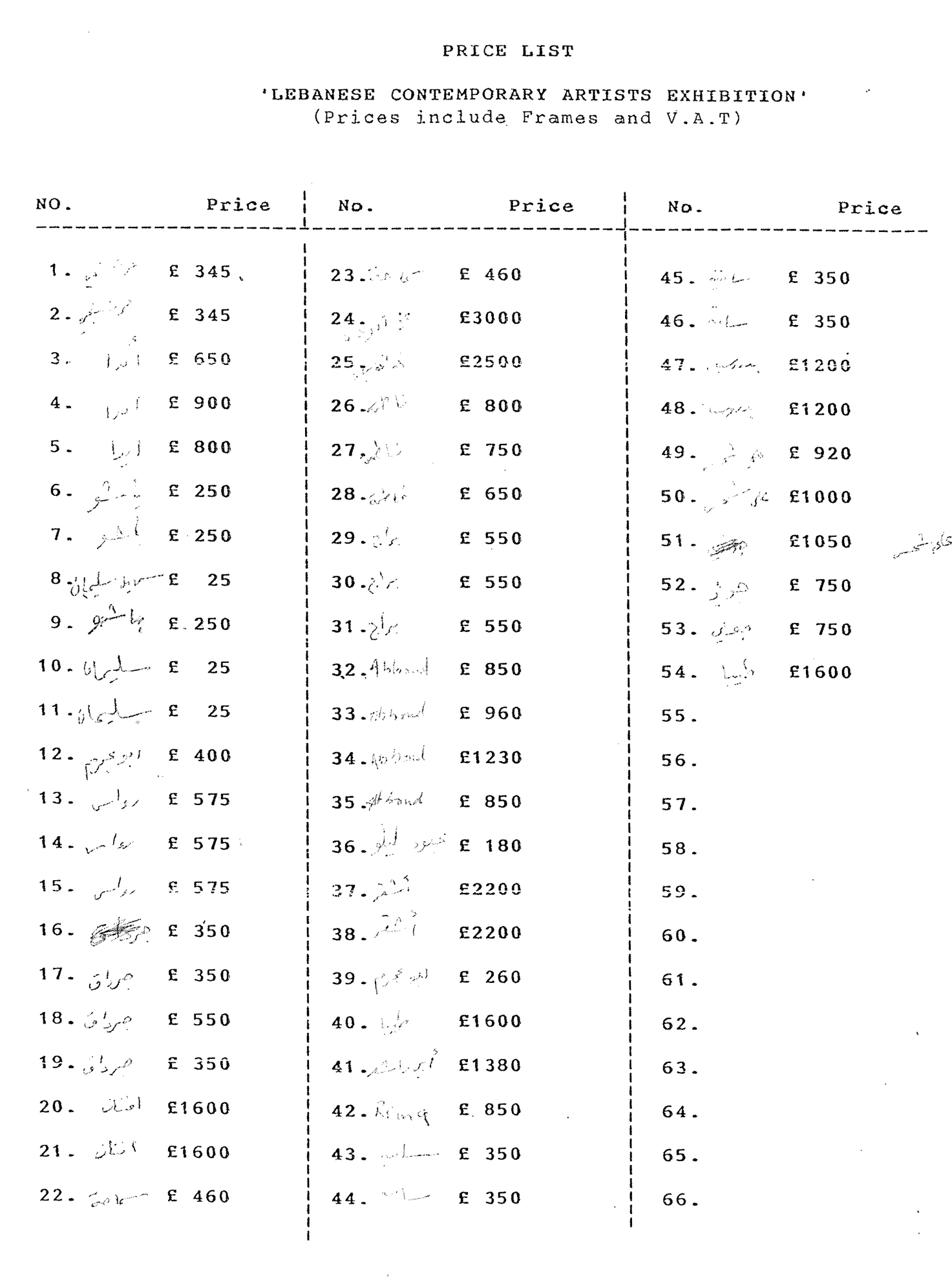

Nadia: In one of the articles, it said they sold between 25 GBP and 3,000 GBP.

Rose: Imagine.

Nadia: 3,000 GBP for a Paul Guiragossian.

Rose: That’s it. The most expensive was Paul Guiragossian.

Saleh: I can tell you who was there with prices. Aractinji had two paintings. Ida Alamuddin had three. Ginane Basho had two. Suheil Suleiman had one. Another Basho, two Suleiman. Abu Ajram, three Rawas. Three Jurdak. Two Afnan. Sumayya Samaha, two. Guiragossian, two. Fatima El Hajj, three. Barrage, three. Abboud, five. Ashkar, two. Abu Ajram, again. Tiba, Abi Rashed, each had one. Rima Amyouni, one. Samia Osseiran had four. Henrig Bedrossian had two. Ali Shams, three. Jouni, two. And Tiba, another one (fig. 3).

Nadia: One thing about the reviews is that most of them were from Arab newspapers. And all of them were mentioning the absence of the war in the works, and then also comparing the artworks to Palestinian art.

Rose: That was the main critique at the time. There was lots of abstraction. I felt the only one, strangely, who talked about war was Ida Alamuddin, because her work was in charcoal, black. And she painted bitter lemons, they were like two lemons in a bag, but it looked like testicles, like you have castrated us. It was a beautiful series of paintings she did, I must say. And the darkest one also. That is why I put one of her works on the poster of the exhibition (fig. 4).

Nadia: Let’s take this article by al-Dustour (25 January 1988), in which we read that “despite the efforts of Kufa Gallery, the exhibition was not a success.” The correspondent criticized that one did not see anything about what Lebanon was suffering at the time, nor the “Arab resilience in front of the Zionist bullets,” continuing that “we are not against imagination and beauty and freedom of artistic expression, but even Picasso escaped the world of hallucinations to create Guernica,” concluding that “in truth, we saw in this exhibition the tragedy of Lebanese ‘art,’ and not the tragedy of the Lebanese ‘people’.” It was subtitled “An exhibition without a cause” (fig. 5).6

Rose: This is Suleiman next to me, and next to that the novelist Hanan al-Sheikh. A lot of writers came to Kufa, it was a gathering place. They called it Diwan Kufa, bringing together all the Arab intellectuals of London at that time. We did not have any Institut du Monde Arabe, it was just opening that year in Paris. That was Ida Alamuddin. Do you see her there on the bottom right?

Nadia: In front of one of her works, yes.

Saleh: Actually, the papers are criticizing that it was somehow non-curated, but obviously it was more related to the conditions of Lebanon, trying to gather artworks that were available to you in order to help the artists.

Rose: In 1988 nobody used the word curator.

Saleh: I know, but I am just looking at the names and I am trying to understand how they were selected.

Mohammad: When I see this article signed by Mohammad Makhlouf, I don’t know who he was, but look, most journalists had this mentality. When he says that he visited the exhibition with a friend, and that this British friend was so angry because he saw nothing about Lebanon’s war, asking “Where is the tragedy of Lebanon?” [the title of the article]. Makhlouf writes:

Considering that what he saw does not express the people of Lebanon and its issues, I don’t blame him. The exhibition does not in any way point to what is happening in Lebanon. […] So instead of seeing paintings that talk about the faces of hungry Beiruti children or the victims of the Israeli bombing, instead of that, they showed the bodies of naked women in a vulgar way. Dead flowers.7

With the dead flowers he is probably referring to Ida’s work, and the naked women to my work (fig. 6).

Saleh: This is a stupid writer. I am saying that I can understand the situation. You want to export artworks to London. Back then it was not like a museum was working on the idea of curation. The artists sent their nicest works. Because when you paint the war, nobody wanted to show it back then, at least in Beirut. The artists used to paint the war and put these paintings on the side, and nobody saw them. Aref El Rayyes has never shown his war paintings. Amine El Basha has a series about the war, but until now it has never been shown. So I understand that in this exhibition, the war was not present. And the Londoners are coming to this exhibition to see colourful, nice works that are meant to be sold in order to support those artists.

Rose: We did not put it as a criterion that it should be colourful and saleable. No, this was not a criterion.

Mohammad: The level of those people who covered the exhibition, who knew nothing about art, astonished me. One article says about Paul Guiragossian, for example, “he is still sleeping in abstraction.” Give me a break. You are somebody who is coming to write a critique on an art exhibition.

Rose: We don’t have art critics, I can tell you.

Mohammad: Listen, or “Samir Abi Rashid, he is still drowning in the Surrealist world full of hallucinations and sweet dreams […] the taste of which the people of Lebanon have forgotten.” Then “Another artist,” now he comes to me, “Mohammad El Rawas paints for us strange atmospheres far from our heritage. Tens of canvases repeat the English painter David Hockney.” I could not see any relation between my work and his work! “And in one of these works, we see naked girls”—his problem is nudity, you see—“sitting close to the English painter called Peter Blake.” That’s true, I did put Peter Blake in this painting. Listen to what he says. “And we ask: Who is Blake, Rawas?!! What did he offer to the Arab cause? And we ask with a broken heart: Why did he not paint for us (for example) or point us to the Palestinian artist Ghaben.”8 Anyway, this sums up, actually, the attitude in all this press.

Nadia: And quite a lot are comparing Lebanese to Palestinian art, saying that Palestinian artists were actually showing the struggle. This article in al-Arab (19 January 1988) also includes another reference to Guernica, writing that “of course we don’t expect a Lebanese Guernica, but we expected to see something that tells us about the terrible things happening in Lebanon,” discussing how in comparison to what most Palestinian artists present in their works, they saw the exact opposite in this exhibition.

Rose: Well, the Palestinian struggle started well before, in 1948. They had time, by 1988 it was forty years. In Lebanon, it was different. I mean, you cannot go to Paris and see Shafic Abboud and tell him to do a painting about war. You ask, “What are you doing?” And if it is quality, we take it.

Ashraf Osman: But what do you think about the hesitation about making war art during the war, because as Saleh said, it was here as well as abroad that artists did not generally want to show their works about the war.

Saleh: I would not say they did not want to. Let’s look at today, and imagine somebody comes to you with a series that is absolutely black and full of cadavers. Maybe as a gallerist you would say it’s a very strong series, I should show it. But I will tell them, not now, wait a little bit. I always think showing violent works should be during times of peace, where people have some distance. If you show it today, probably many people will appreciate it, but you will not sell a single painting. It’s a question of context. You are under the bombs. People need some escapism in what art they want to buy during a period of violence.

Ashraf: Yes, the mention of escapism is very present in the press clippings of the 1980s.

Saleh: I understand it. Imagine I am an artist in 1988. Mohammad Rawas proposes to me to give him some paintings to put them in an exhibition in London, and I don’t have a penny. The Lebanese lira at the time went from 2.253 for the dollar to 3,000. So Mohammad proposes to me, I want to take two paintings from you. I give him two paintings full of bodies and blood that nobody wants to buy. Of course not, I will give him a nice painting that I would say can sell. I mean, I’m talking about why they look rather happy. The exhibition was not asking artists to give something that represents the war today. But for me, the exhibition is important because it is probably one of the first instances where the idea of exporting art to outside Lebanon was proposed as an idea.

Rose: It truly was, Saleh. We did not sell much, actually, which was a very sad thing for me. The gallery was new. We tried to lobby a lot. Still, the mentality of buying among collectors was practically non-existent. The main thing was that we wanted to do an event, talk about Lebanon, and if possible, support the Lebanese financially.

Mohammad: Personally, when I went to London to study at the Slade School of Fine Art between 1979 and 1981, all the work I did was about the war in Lebanon. All the prints, silk screens, etchings, everything. When I came back here in 1981, I did not want to do so anymore, because then I was living the war again. When you are taking a distance from it, you can reflect on it and express it with a space of artistic effort, or creativity, or professionality. But when you are living in the event, the event is eating you. All the works that I did after my return were a sort of escapism. And the one I exhibited at Kufa in 1988 is one of them (fig. 6).

Rose: I will tell you another example. We introduced Maliheh Afnan to the public. All her work was about destruction and cities, see for instance Beirut (fig. 7). She was of Iranian-Palestinian origin, and all her work was about burning and exile. It did not look like war, but it was about loss. It was about cities that were gone, places you lived. Everything was charcoaled on the back. But those critics, of course, did not see it this way.

Saleh: They were not actually art critics, they were just journalists, using jargon.

Rose: It was difficult. They used to come to the gallery and wanted only to photograph the beautiful girls, as if they wanted to find them a husband. I said, no, if you photograph somebody, it has to be next to a painting. I don’t want an article without an artwork. It was always a fight, almost, to make sure that there was some painting behind everybody they photographed.

Nadia: Can I read you an excerpt of an interview with Hugh Casson, who was on the jury of the exhibition Lebanon—The Artist’s View (London, Barbican Centre, 15 April–4 June 1989), which came just after the Kufa exhibition?9 He said of the Barbican exhibition:

I was surprised at how few paintings of war scenes there are, unlike wartime Britain; no protest, no horror, no ruins. At first I suspected escapism but I wonder if it isn’t that the war is too much under their feet? Or perhaps there was a purpose in the Second World War that inspired the likes of Piper, Sutherland and Nash that doesn’t exist in the Lebanon? Or is it a reflection of the miracle of normality that also seems to be part of the Lebanese?10

Rose: Casson lived very close to Kufa Gallery, maybe two hundred metres away. He used to come to the gallery. His friends were all bankers of the Middle East, so he knew a little bit the history of the region. The problem is that he does not mention that the war paintings of the British were largely commissioned.11 In Lebanon, there was no state commissioning any artists to produce records. But in Britain and in America, everything was recorded by the governments who commissioned artists to record. It was not that people in London were simply painting war, no.

Saleh: Actually, all artists are sensitive to what is happening around them. But sometimes they would reflect on their surroundings, put the work on the side and want to show something else. And contextually, at that time in 1988, there was no idea of a curated show. And the West was very self-centric. For them, there was no art in the periphery.

Rose: Yes, Tate Modern did not exist. London had only one museum, that was Tate Britain. And Tate Britain only collected British artists. I remember once they had an exhibition on British Orientalists and they asked me, can you come and help us, and do an answer to that?12 This was later, in 2006 or 2007. I said, yes, I will come. But every time I proposed somebody, they said, “We don’t know them, how many monographs do they have?” This is why I started working on publications, because unless you have three monographs of an artist, they wouldn’t even consider them. They liked the work that I was proposing, but I did not have three monographs on each artist.

Saleh: In 1988, they were very Western-centric. The rest of the world were considered underdogs. So I think what is extremely important about this exhibition is that it opened a door, actually, to making them look and know there is something else out there. At that point in time, probably they looked at it in a very condescending way. But eventually, twenty, thirty years later, things have changed. Now there is more openness.

Rose: Now they feel guilty. If they don’t do global art, they are backward. If they don’t open up to other cultures and others, they are backward. They know that they are obliged to do black art, they are obliged to do gay art, they are obliged to do old ladies, and so on. The fashion moves on. And they know that they will stay backwards if they don’t open up, because lots of other institutions have opened up.

Nadia: Mohammad, you studied in London in the late 1970s, early 1980s. How did you feel there in terms of your surroundings?

Mohammad: There was no interest whatsoever in what was going on outside London. At the Slade School of Art, colleagues knew I was from Lebanon, but I wasn’t sure if they knew where Lebanon was. One of the technicians, a silk screen technician, was helping me with my work. He said, “What is this crazy leader you have, Qaddafi?” I said, “Qaddafi? Qaddafi is from Libya.” He said, “Libya? Where are you from?” I said, “Lebanon.” He said, “I don’t know the difference.”

Nadine: What’s the difference…

Rose: I wanted Nadine to come today, because it is interesting to know also what was happening in Lebanon in the 1980s. Dar El Fan was still functioning, your mother was still doing things, although the building was damaged.

Nadine: The building was gone. But in 1989, my mother did an exhibition at Dar El Nadwa, a very big one. It was Beirut, Tabaan (Beirut, of course).13 It was her bye-bye, like a testament. You also had exhibitions at the Carlton Hotel, and at the Goethe Institut. The Goethe Institut was marvellous, really.

Mohammad: Beirut, Tabaan was covered by German TV, I have a video.

Nadine: It was the last exhibition of my mother. And in this exhibition, she really wanted to introduce young, emerging artists. She started with Jad (Georges) Khoury, who did comics. This was one of the first exhibitions in Lebanon where you could find comics and this kind of work. You also had very new artists, like Greta Naufal. My mother put the new, the young, the emerging, and the others.

Nadia: And the idea was to reaffirm Beirut.

Nadine: She wanted very much to say, “I’m leaving, but there are a lot of things to do.”

Nadia: And for Kufa Gallery, Contemporary Lebanese Artists was one of the first exhibitions, at the very beginning of the gallery.

Rose: Yes. Just afterwards, I did an exhibition with Arab women artists in the UK, because I wanted to know how many there were. Can you believe it? There were more than twenty Arab women artists in the UK, none of them knowing each other. For me, it was an occasion to introduce them. It was the first time I exhibited Mona Hatoum. Imagine, the video of Mona Hatoum that I showed in 1987 was acquired twenty years later by the Tate. That same video. At the time, neither Mona Hatoum nor me knew that we could sell video, nor photography. I had her Over My Dead Body, the beautiful photograph, behind my desk.14 And nobody asked, can we buy a photo or can we buy a video? This was not at all fashionable then. So we have to think that the word curator did not really exist, the word video art did not exist, even photography did not have a market, really. It was for me an occasion for all of us to meet each other.

Mohammad: Where did you have this exhibition?

Rose: At the Kufa Gallery. Arab Women Artists in the UK, from 25 March to 14 April 1988. If you go to my website, you can see it.15 The poster was the work of Sabiha Khemir. And with every exhibition we tried to build up a community, in fact, because there was no community. Kufa became so important by 1988 that even Indians, Africans, everybody wanted to exhibit in the gallery. I did not have a penny to do catalogues. I usually did a very good press release, in black and white.

Nadine: So you wanted to build a gallery on the basis of quality and create a community around it.

Rose: Yes, the community aspect was important.

Nadine: It was not easy in the 1980s.

Rose: No. To give one example: You see, Mona Hatoum was in this exhibition, with video work, at the time when she was doing performance. I remember that even my close friend said, “What is this video? People are not going to like it.” So I even had opposition among my friends against including the video.

Nadia: Had you thought about including Mona Hatoum in your exhibition of Contemporary Lebanese Artists?

Rose: Not really. At that time, she was more known in London as a Palestinian artist, Palestinian-Lebanese, and she was doing performance art and video work.

Nadia: You knew her from the Slade, Mohammad, because you were there at the same time, weren’t you?

Mohammad: Yes. I was doing printmaking, she was doing experimental art. We did not become friends, just acquaintances. Sometimes, when I was going to Lebanon, she asked me to send her parents a letter or something. This kind of thing.

Rose: Anyhow, she is a very discreet person, not a sort of social animal. She waited a long time before engaging herself with a gallery. She was very patient. She said, I am not going to engage myself with any gallery before I find the right one. She waited almost twenty years before going with the White Cube. For so many years, she was on her own.

Nadia: Was this unusual for London at the time?

Rose: Not really, because there were very few people who really understood. You know, Zaha Hadid, it took her also twenty years before they showed her paintings, let’s say at the Metropolitan in New York. When they showed the drawings she had, they put her down as a British artist. I went and complained to the Metropolitan. I said, no, she is Iraqi, she always presented herself as an Iraqi artist. But they would not associate Arab names with anything positive. So even Mona Hatoum is in the Tate labelled as [a] British artist. They would never put British-Palestinian, let’s say.

Nadia: This gives us an idea about the environment the exhibition took place in. Your work is really important, Rose. Thank you so much to all of you for taking the time to reflect on this exhibition and the context in which it took place.

“Al-Alwan al-musafira la tuhibu… al-harb!” Al-Sayyad, 25 February 1988.

Contemporary Lebanese Artists. London: Kufa Gallery, 1988. Catalogue of an exhibition held at the Kufa Gallery, London, 15 January–24 February 1988.

“Exhibition at the Barbican, 15th April 1989 to 4th June 1989, ‘Lebanon: The Artist’s View’.” Loose pages on the exhibition from the archives of Joseph Tarrab hosted by the Orient-Institut Beirut.

Exhibition Review [title unknown]. Al-Alam, 20 January 1988.

Exhibition Review [title unknown]. Al-Tadamun, 23–29 January 1988.

Grandjean, Joan. “Mona Hatoum’s Other Story: ‘Third World Post-modernism’ in 1980s Britain.” Manazir Journal 7 (2025): 190–222. https://doi.org/10.36950/manazir.2025.7.8.

Jebara, Lisa. “Ghiyab lubnan fi m’arad lil-fananin al-lubnaniyin fi London.” Al-Majalla 416 (27 January–2 February 1988), n.p.

“Londres a l’heure de 20 ‘artistes libanais contemporains’.” L’Orient-Le Jour, 14 January 1988.

“London tashhad thalath munasabat fanniya lubnaniya.” Al-Arab, 19 January 1988.

Makhlouf, Mohammad. “Ma’sah ‘al-fan’ al-lubnani! M’arad bidun qadiya.” Al-Dustour, 25 January 1988, 52–53.

Malusardi, Flavia. “The House Stands Tall: The Social Dimension of Dar el Fan and Janine Rubeiz’s Curatorial Activities during the Civil War in Lebanon.” Manazir Journal 7 (2025): 83–107. https://doi.org/10.36950/manazir.2025.7.4.

Maltzahn, Nadia von. “‘I Have a Friend Named Time’: Interview with Greta Naufal.” Manazir Journal 7 (2025): 222–47. https://doi.org/10.36950/manazir.2025.7.9.

Nuri. “al-Bahth ‘an al-hawiya min khilal al-ahzan!” Al-Hawadith, 29 January 1988, 56–57.

Rose Issa Projects. “Arab Women Artists.” Last accessed 11 June 2025. https://www.roseissaprojects.com/gallery-individual/1987---1989---arab-women-artists.

al-Tamimi, Nazira. “Muhamad al-Rawas: Laisa matluban min al-fanan an yarsum hasab al-talab.” Al-Qabas al-Dawli, 8 March 1988, n.p.

“Tard al-hayat min fada' al-lawha.” Al-Ufuq, 10 March 1988.

Tate Britain. “The Lure of the East: British Orientalist Painting.” 4 June–31 August 2008. https://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-britain/lure-east-british-orientalist-painting#.

Nadia von Maltzahn is the principal investigator of the ERC-funded project “Lebanon’s Art World at Home and Abroad: Trajectories of artists and artworks in/from Lebanon since 1943” (LAWHA), based at the Orient-Institut Beirut (OIB) where she previously held the positions of Deputy Director and Research Associate. Her publications include The Syria-Iran Axis: Cultural Diplomacy and International Relations in the Middle East (London 2013/2015), the co-edited volume The Art Salon in the Arab Region: Politics of Taste Making (Beirut 2018), and other publications revolving around cultural practices in Lebanon and the Middle East. She holds a DPhil in Modern Middle Eastern Studies from St Antony’s College, Oxford. Her research interests include cultural politics, artistic practices and the circulation of knowledge. LAWHA examines the forces that have shaped the emergence of a professional field of art in Lebanon in local, regional, and global contexts.

Rose Issa is a curator, writer and producer who has championed visual art and film from the Middle East and North Africa in the UK for more than thirty years. She has lived in London since the 1980s, showcasing upcoming and established artists, producing exhibitions with public and private institutions worldwide, and running a publishing programme.

Mohammad El Rawas is a Lebanese painter and printmaker. He studied arts at the Lebanese University, then moved to London and studied printmaking at the Slade School of Fine Art. He currently lives and works in Beirut, where he taught at the Lebanese University and the American University of Beirut.

Saleh Barakat is a Beirut-based gallerist and art expert. He runs Agial Art Gallery and Saleh Barakat Gallery in the Ras Beirut area.

Nadine Begdache is a Beirut-based gallerist and art expert. She runs Galerie Janine Rubeiz.

Ashraf Osman is a PhD candidate in history of art at Ca’ Foscari University of Venice and the Orient-Institut Beirut as part of the LAWHA project.