Three colourful tapestries, made by Amine El Bacha and Antoine Saadé in 1984 and 1985, emphasize processes of creating connectivity in wartime Beirut. Their shared project of intermedial imagination and translation adapted Aubusson-style techniques to a modified loom embedded in a longer history of silk weaving in Lebanon. Their slow, creative process not only ensured the medium’s continuance during the war but was also an enlivening force that deepened their artistic affinity and friendship. Forged within an experience of forced displacement, this bond speaks to the entwinement of artistic process and modes of social and ecological connection. Based on personal testimonies and collections, this article reconstructs an intimate art history gleaned from the layered processes of making and remembering, in which picnics in nature, shared meals, and loom building form an integral part of the engagement.

Textile, Sensory Process, Collaboration, Interdependence, Memory

This article was received on 24 July 2025, double-blind peer-reviewed, and published on 17 December 2025 as part of Manazir Journal vol. 7 (2025): “Defying the Violence: Lebanon’s Visual Arts in the 1980s” edited by Nadia von Maltzahn.

Three colourful tapestries, made by Amine El Bacha (1932–2019) and Antoine (Antoun) Saadé (1936–2012) in 1984 and 1985, emphasize processes of creating connectivity in wartime Beirut. Their shared project of intermedial imagination and translation adapted Aubusson-style techniques to a modified loom embedded in a longer history of silk weaving in Lebanon. A weaver from Zouk Mikael, Antoine was known for his aesthetic sophistication, versatility, and innovation, notably the adaptation of a type of horizontal floor loom that elevated the weaver above the floor.1 Amine was an artist from Beirut for whom sensory experiences, notably in the genres of painting, literature, and music, converged in practice. Their slow, creative process not only ensured the tapestry medium’s continuance during the war but was also an enlivening force that deepened their artistic affinity and friendship. Forged within an experience of forced displacement, this bond speaks to the entwinement of artistic process and modes of social and ecological connection.

Based on personal testimonies and collections of tools and materials preserved by the widows and daughter of the artists, this article reconstructs an intimate art history gleaned from the layered processes of making and remembering.2 Picnics in nature, shared meals, and loom building form an integral part of the holistic engagement. Archival traces of tapestry-making among artists who left Lebanon early in the war situate the project and emphasize its relational nature. As artists Nicolas Moufarrège (1947–85) and Paul Wakim (b. 1949) affirm, it was the generative process that mattered most and retained shape in memory. Throughout the text, the use of first names rather than surnames is a gesture toward the intimate nature of friendship and close cooperation, and of engaging familial histories and fragments. The article’s narrative structure takes place in three distinct settings to frame the collaboration before turning to the process of creating.

Saada sat behind a tall wooden structure, shielded from the sun in a back corner. Quiet, concentrating, fingers pulling the threads before her. The loom’s long wooden beams feel soft and worn beneath her touch. The nawl (loom) is strung with unwoven fibre, looping in its continuous path above and through the device; the transformative motion of her hands and shuttle intersects their linear march. Sunlight pours into the cool dark sanctuary from an open doorway. The scent of the sea rolls in to mix with dust.

My presence disturbs her serene meditation. We exchange greetings, words, silences filled by the rhythmic beating of the heddle bar. My eyes rest briefly on small white bones, hanging sculpturally against the bare wood, tied through twists of braided rope (fig. 1). When I ask Saada about them, she reaches, almost automatically, to caress their smooth delicate structures. She smiles slightly, inwardly, a slow pause before she speaks. “They are bones from a shared meal,” she discloses, when, during the war, “we slaughtered and prepared our own sheep.”3 We return to stillness as she weaves.

Bones operate as joints, enabling the heavy, chest-height heddle bar beating weft into warp to move back and forth while affixed to the larger loom structure. Strong and enduring, they are better than manufactured metal parts, she says, and last longer. They do not damage the fibres. Left implicit is their reliquary function, traces of a family meal, the nourishment of a husband and son, now deceased, a distant daughter living abroad, the eyes of whom gaze at us from faded photos on a wooden shelf. Loom construction and human preservation are, in this space, indelibly connected, recalling the words of artist Paul Wakim, “when the wood is fragrant, the bond is stronger.”4 Paul’s embodied, sensory memories of wartime forest walks, during which he gathered materials to make loom parts, inform my reading of this story.

Saada’s loom was Antoine’s invention. The family used to tease him for working above ground level, but his ideas spread quickly among the other weavers of Zouk Mikael who once used pit looms of a kind imported from Syria.5 They wove across genres, prolifically and imaginatively. Fabric for cushions and slippers, luxury silk abayas, ecclesiastical cloths, “Aleppo purses,” modernist tapestries. Antoine was a master weaver and teacher, renowned in Beirut and beyond.6 He did not just instil knowledge from father to son, as was historically done in Zouk. He taught women, including Saada, his wife, during the war around 1986 when they lived in Beirut’s Hamra neighbourhood; their loom overtook an entire bedroom. Antoine also, in those years of displacement, taught Amine El Bacha the laborious techniques of Aubusson-style tapestry, bringing the painter’s melodious birds, suns, and stars to life with his hands.7

A typewritten letter recovered in a Swiss archive casts a glimpse into the raw experience of one tapestry artist displaced from Beirut by the war. Undated, circa July 1978, it tells of loss, destruction, and suffering. In her account, Dale Egee (1934–2017), one of Antoine’s apprentices and collaborators, wrote:

In Lebanon we have lost everything. There is no tapestry weaving in the four villages where we worked together [Zouk Mikael, Nabha, Qab Elias, Aïnab]. Antoine Saadé’s studios were blown up along with every piece of finished work. Antoine fled to Cyprus with his wife and baby and is weaving cheap carpets for the local trade. Selim Saadé [Antoine’s brother, husband of Saada’s sister] is working in a restaurant, Farouk Hashem [Saada’s brother] is a bodyguard. All the weavers of Nabha have fled. In Qab Elias, Amal’s father was machine-gunned to death and his home dynamited. Amal [Yamine] is a maid in the city now. Marie [Badr] works in a distillery, capping bottles. The atelier is dusty and abandoned. The Carons have left Aïnab without a trace. We have settled in Dubai on the Arabian Gulf, after a brief period in Rome.8

On its own, the letter crafts a narrative that the war was a definitive barrier to the medium’s continuation. Dale mourns the dispersal of her associates, their lost plans (fig. 2). She speaks of an exhibition of their contemporary tapestry, which was in preparation for the Sursock Museum but regrettably cancelled, all possibly forgotten.9 She could not have known that her letter, once opened and read by the jury of the ninth Lausanne International Tapestry Biennale in 1979, would be placed into one of hundreds of boxes on a shelf, and that these boxes contained thousands of other rejected applications, including from Lebanon.10 She did not foresee that these archival, photographic, and fibre remnants might yield an alternative story, a retelling.11

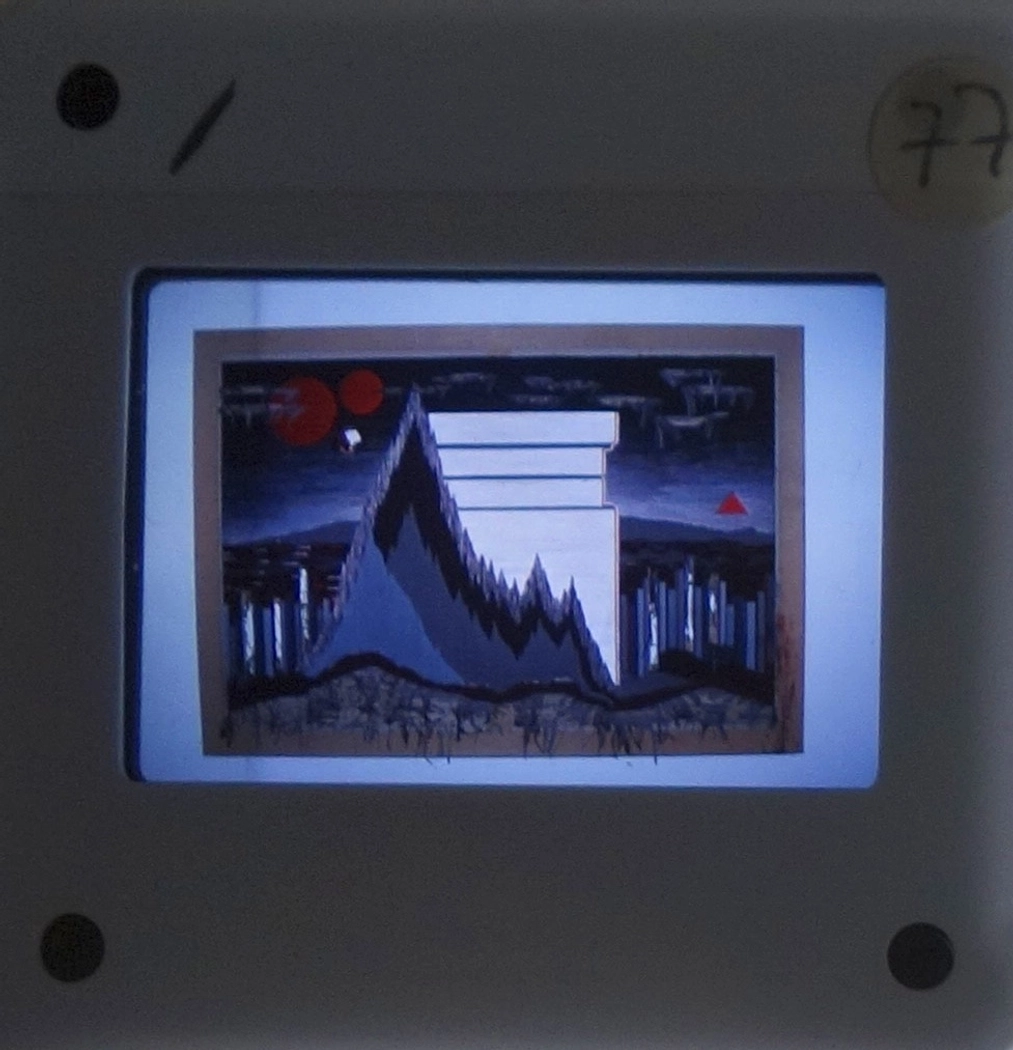

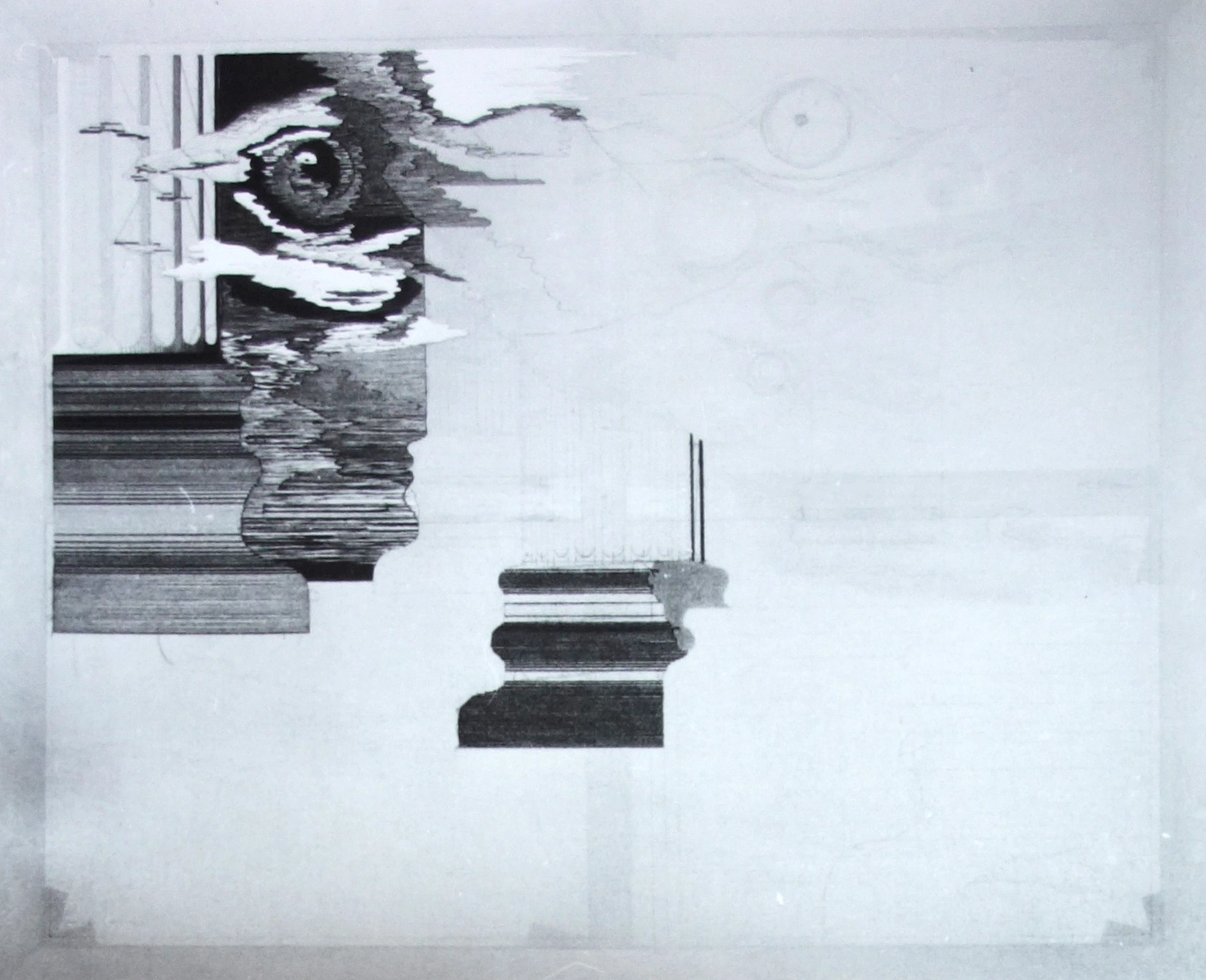

As part of his meticulous application to the ninth Lausanne Biennale, Nicolas Moufarrège (Mufarrij) submitted two sheets of colour slides encased in plastic with a handwritten list of artworks. His first slide was entitled al Harb (un dimanche presque commes les autres, Sunday August 13, 1978).12 Referencing the bombing of a nine-story apartment building in Beirut, which killed around two hundred people, Nicolas created a dark, ethereal fibrous landscape. This embroidered textile consists of blue and white floating rectangles, a mountain spiking like a seismic pulse, and red orbs flashing in the sky (fig. 3). Loose threads dangle from fiery discs and wriggle from the blue-brown rubble at the bottom of the work, twisted like hanging debris. Aside from its more literal depiction, the hanging threads also seem to suggest an un/doing which transcends the finality of completed work, casting shadows over any presumption of an object or event as detached or resolved. Fitting, then, that Nicolas’s proposed tapestry, entitled Phoenix, was still a work in progress at the time of submission, traced in pencil on needlepoint canvas, only one eye of the rising creature fully stitched (fig. 4). “The work has been born, and transforms as the days pass,” he wrote in an addendum to his application form.13

Like many works in fibre made during the 1970s and 1980s, al Harb and Phoenix are not tapestries in a strict technical sense. In the biennale forum, the nature of the tapestry medium and the appropriate terminology for its various expressions were fiercely debated and contested for more than two decades.14 Some exhibiting artists engaged historical practices of cartoon-making and wall tapestry, while others experimented with fibre’s pliability, softness, and spatial parameters to create textured, dimensional works equated with what critic André Kuenzi called “new tapestry.”15 By the 1980s, artists like Nicolas were creating fibre and cord installations, textile assemblages, or woven environments emphasizing the tactility of art forms deemed outside the realms of high art and traditional tapestry. At the same time, some artists and critics based in Europe and North America rejected what they perceived to be the rote, mechanical processes of pictorial tapestry, deriding a division of labour that often separated the artist-painter from the weaver-labourer; in this conjecture, the weaver “executed” a painting from a cartoon (a full-scale numbered model) with little imagination or insight. Collaborative making and shared creativity were frowned upon in dominant discourse in favour of the exaltation of the singular artist-genius liberated from the constraints of craft.16

While Nicolas’s practice combined embroidery, collage, and painted cloth, he identified this early needlework as tapestry (though humbly noting he was an “autodidacte [de la] tapisserie” on his biennale application). He likened his artistic process to a reconciliation, a conjoining of roles, using metaphors derived from his graduate training in chemistry. “A tapestry is like a chemical reaction,” he once explained to readers of the Lebanese weekly magazine La Revue du Liban. “It is the brain that directs the hand’s action. But at the same time, it is the hand that tells the brain what it can do. It’s a kind of balance between two spaces or several individuals or even the inner compartments of a person” (emphasis added).17 At its heart, then, tapestry comes into being through the forming of relations. It entails a bonding and the establishment of transformative connection.

Trauma, loss, and amnesia pervade some reflections about this period of Lebanese history, but contrary to Egee’s grief-stricken letter, tapestry and collective making continued during the civil war. Of these practices, few sought to depict deadly imagery or specific violent events like Moufarrège’s al Harb. As represented by the submission of the Phoenix (in progress), it was the very process of becoming, of tracing, of tending, of creating that mattered and retained shape in memory. Artists and families remembered endeavours to preserve a balance, an equilibrium. They recounted a form of reciprocity created through the slow processes of loom building and preparing tapestry cartoons, in connecting socially and with nature, even before winding the threads onto the loom beams and into the shuttles, well before interlacing weft with warp.

Stacked on tables in thin papery layers, hand-drawn images stretch across the expanse of the long narrow room. Rolls of unused tracing paper keep the sheets in place, although no breeze stirs the humid air today. We approach the piles: brown, slightly ruffled, some pages with lightly torn edges (fig. 5). Clear tape fastens certain pieces together like a paper patchwork quilt. Leaning closer, we detect faint pencil lines beneath marker. It appears that a hand holding a black, sometimes blue, marker has traced over and around the finer markings; these thicker lines overlay the contours and widen the edges of each shape, a reinforcement. The dark lines have a fortifying visual effect, strengthening the design for the eye’s ease in interpretation. A number floats in each distinct shape, one per field.

“Whose handwriting is this?” I wonder aloud, in reference to the numbers (fig. 6). They appear as numerical digits, and occasionally, in word form. Angelina moves closer, bending down to scrutinize the small shapes. A red ink number hovers above a pencilled one in these scores of numbered fields. It is difficult to discern, she admits, sifting through the pages, “I need to see a five.” After initial hesitation, she concludes, “it is Antoine.”18

Between 1984 and 1985, Antoine and Amine engaged in the long, slow process of creating a series of tapestries drawn from the material and symbolic repertoires of both artists. Together, the two men discussed, drew, envisaged, and transformed Amine’s designs into multiple cartons (cartoons) and three large-scale weavings. Their shared project entailed shifting between paint, paper, pencil, ink, wool, and cotton, as well as between modes and scales of working. The faint tracings on the brown papers covering the tables of Amine’s studio in Hamra form the initial outline of what would eventually become a section of woven tapestry, while the numeric notations encode the colour palette. The reinforcements in marker and ink finalize the two-dimensional input that Antoine deployed in reimagining his friend’s paintings in wool; all the while he never lost sight of the floral, vegetal, and abstract shapes inhabiting the silk textiles of his own design.

The resulting tapestries materialize the careful, protracted processes of creating art and connectivity in the changed cartography of Beirut. Undoubtedly, the 1980s saw disruption to arts events and institutions as people experienced ongoing devastation, separation, and uncertainty. Dale’s letter and Nicolas’s al Harb speak to these disturbances in different ways, and both artists submitted their applications to the ninth Lausanne Biennale only after fleeing Beirut for Dubai and Paris.19 Yet, the 1980s were also a time in which creative practices developed despite, and even because of, this divided terrain and forced mobility. As Saada’s delicate yet powerful bones indicate, hidden art histories can be gleaned from the layered processes of making, which in turn form and are formed by bonds. Nature walks, family picnics, neighbourly bonding, and creative collaboration at the loom: these all took place during the war and were at once artistic and community lifelines.

Angelina remembers that “in the war, at a point, there were people one discovered, people who were known through their friends. It was like that. People grouped in new ways.”20 Movements of people whose lives had not formerly crossed enacted bonds of friendship. When Antoine and Saada returned from Cyprus after years abroad, resettlement in Zouk Mikael was not possible. Rather, in 1984 they found an apartment in Ras Beirut near Hamra Street that was incidentally located near Amine’s studio and intermittent family residence during the war.21 They moved in with at least one loom. A mutual friend and neighbour introduced the painter and weaver, who had learned about each other through word of mouth. Angelina recalls how Antoine “brought an atelier with him.”22 Restricted in mobility and spending long periods indoors, the two men embarked on a multi-year collaboration spanning the war’s third and fourth phases, which saw the aftermath of the Israeli invasion, the war of the mountains, and heavy internal fighting.23

Amine and Antoine created tapestries based on Amine’s paintings, generating them via the slow, meticulous process of cartoon-making. This intermediary stage facilitates an intermedial transformation, one in which a painting metamorphizes into a weaving on the loom. In the mid-twentieth century, cartoon-making became known in France and the Francophone world following a collaboration between Jean Lurçat (1892–1966) and François Tabard (1902–69) in the historic village of Aubusson.24 Building on earlier networks of artists and institutions seeking to reform and reclaim the valour of French tapestry, Lurçat popularized his techniques and approaches through writing and promotional activities.25 He led the Association des Peintres-Cartonniers de Tapisserie for artists engaged with the translation of their paintings via the carton numeroté.26 The group exhibited widely in France and internationally, including in Lebanon and Syria in 1951.27 Ten years later, Lurçat cofounded the Lausanne International Tapestry Biennale, which would, following his death in 1966, become a site in which the use of cartoons (and attendant issues of labour, craft, and reproduction) became contested.28

Jean Lurçat first exhibited his tapestries in Beirut in 1949, attracting Lebanese patrons who collected the monumental works for their homes.29 His associate Roger Caron (1925–91) began teaching tapestry design in the 1950s at the Académie Libanaise des Beaux-Arts (ALBA) as part of its decorative arts curriculum. To encourage the medium’s uptake, the Sursock Museum (with Roger Caron) organized a competition among young artists in 1963.30 The museum also hosted an homage to Lurçat in 1967, displaying artworks signed by the artist as well as commemorative tapestries woven in Zouk and Aïnab, two of the weaving villages mentioned by Dale in her letter.31 In the years leading up to the war, Roger and his wife Monique, an Aubusson weaver, established the “Lebanese Aubusson” in Aïnab in a Druze community in the Chouf mountains, where they trained Paul Wakim in 1975.32 The couple fled to France by the late 1970s, where Roger, too, sought to apply to the ninth Lausanne Biennale, even as his collaborating weavers from the Shaar family remained in the Chouf for the war’s duration. Weavers in Zouk knew and practised “Aubusson” techniques alongside other genres of weaving, as exemplified by George and Elias Audi, Selim Saadé, and, of course, his brother Antoine.

The multitude of drafty cartoons in Angelina’s collection counter any preconception of Amine and Antoine’s work as routinized labour. Laid out before us in these papery layers are the tools and stages of translation, adapted for the Zouk loom. Each number designates a specific thread colour; each cartoon corresponds to a different section of tapestry. Sometimes a hand-drawn arrow points to the continuation of a colour into the next band, overriding a linear divide. Erased pencil lines squiggle into visibility beside cross-outs and corrections. If we strain our eyes, multiple iterations of the design appear, one traced on top of the other. We can almost hear an accompanying dialogue, the voices of Amine and Antoine musing and chatting, “This shade of blue needs to extend over here as well,” or “I reworked your heart to better suit the wool.” It is a messy, creative process that played out over the course of weeks and months.

Organized horizontally across the tables, the cartoons for the three tapestries form a puzzle that Angelina and I try to piece together as we envision the completed work. This mental task is difficult because colour is represented by number only, which requires a unique way of picturing. As novices, we struggle in our attempt. Antoine, however, would have inserted the requisite paper into his loom behind the unwoven warp thread for guidance as he worked, facing one encoded section at a time. As he wound bobbins and wove, Antoine pictured what came before and after the section at hand in memory only. He would need to continuously recalibrate, visually and texturally, the different mediums and the representation of colour and form in each, moving back and forth in his mind as with his hands, which rhythmically guided the shuttle and beater.

In addition to cartoon-making, we are left to imagine the various stages of fibre and loom preparation, undertaken in tandem, which would have spanned months. The two men procured the threads, selecting wools saturated with dyes. Sitting with the painting, they might spend whole mornings looking, drinking coffee, assigning a number to each shade of paint and its colour counterpart in wool. They prepared at least one device, a rainbow chain of threads, a colour key tagged to denote each number; Angelina had preserved this chain, a fibrous archive often stored with cartoons, a trace that could be held, or hung, or touched like Saada’s bones.33 “What size are you envisioning, Amine?” Antoine might have asked as he shared with the painter his careful process of calculation and measurement. “What length do you want the finished pieces to be?” The size of the massive wooden loom helps determine the tapestries’ maximum scale. Angelina recollects the loom was three metres. We do not know if Antoine brought wool with him from Cyprus or if he purchased it locally, or from where he sourced the sturdy cotton warp threads that support Amine’s images.34

Agreeing on the specifications, Amine drew cartoons to scale, spending many hours picturing, measuring, pencilling. Antoine chose a warp thread strong enough to withstand great tension, and began the rhythmic process of winding a warp, measured to the length of the tapestry-to-be. As one continuous thread, it must be wound around and around different posts, looping back on itself to make a cross for the shed (“this is the most critical part, Amine, creating the structure and space for the weft to pass”). Every final turn must be counted. It is at once a kinetic and cerebral process, as the brain makes a notation with each physical turn. Amine would have developed a deep appreciation for the musicality of the movements and the counting, one of many acts that occur before the weaving even starts.

In my mind’s eye, I see a fish, a head and a clock; a leg, a tree and a bottle. I’m interested in putting these forms together, to arrive at a harmony. And that harmony is a story, a story without a subject, without an end or a beginning.35

So said Amine about his paintings before the war in 1972. He presented his intricate, thread-like drawings and vivid, lyrical imagery in the first exhibition of Contact Art Gallery, which also published a small booklet on the artist; colourful gouaches of patchwork landscapes and a bowl of fruit on a patterned tablecloth adorn its pages.36 The work seems ripe for the slow orchestration of cartoon-making, loom preparation, and weaving, not the least because of Amine’s compositional approach, his practice of listening to music while painting, his attunement to kinetic and sensory process.37 The different stages of his collaboration with Antoine would mark the passage of time, a kind of lyricism in practice.

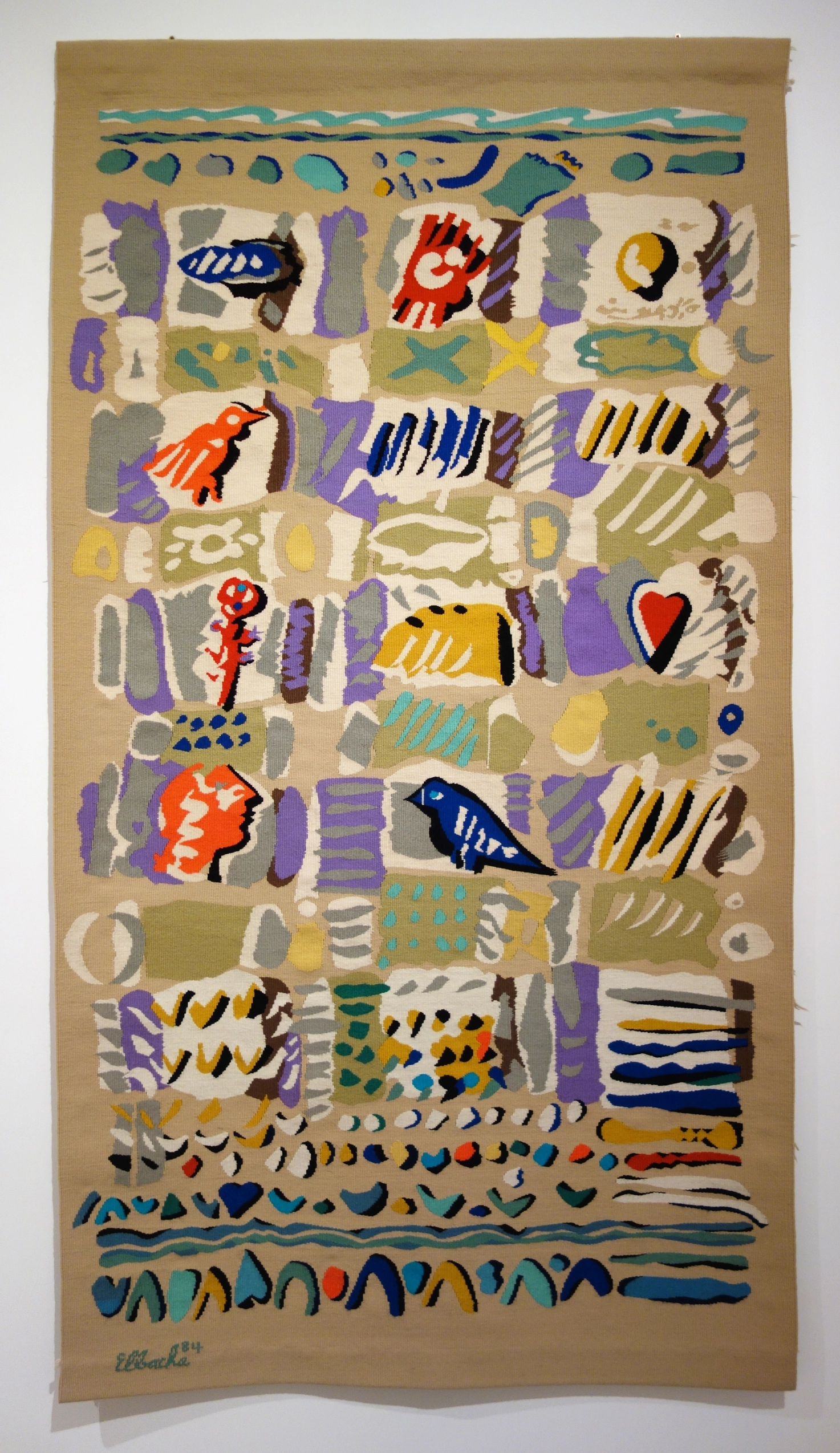

Missing from the studio today are Amine’s original painted maquettes, although Angelina has unfurled two of the finished tapestries in an adjacent room (fig. 7 and fig. 8). Strung across easels, these works fill the space with bright, energetic imagery that seems to celebrate their very existence. We admire the softness of the wool, the seamless textural blending as the threads and colour change, the technical mastery of form, the harmony. “Antoine was exceptional,” remembers Angelina. “Look how he handled colour; what nuance!” She admires Antoine’s translation of Amine’s forms and symbols, his deft handling of abstraction, and attributes this virtuosity to his embeddedness in Zouk’s history of silk weaving. Angelina’s knowledge of Lebanon’s artisanal heritage spills out as she elaborates on how the textile industry had proliferated in Zouk and Mount Lebanon, and among weaving communities in Syria. Levantine silk production flourished with nineteenth-century developments in agricultural production, commerce, and trans-Mediterranean exchanges extending to Lyon.38 Angelina’s respect for Antoine’s lineage would have likely been shared by Amine as their project slowly materialized.39

Amine organized his vibrant compositions into horizontal and vertical registers that seemingly play with the undergirding fibre structure (plain weave) and technical process of construction (fig. 7, fig. 8, fig. 9). Yet rather than creating the appearance of a static grid, each surface teems with energetic flowing lines and symbols of life in bold primary colours. In their patchwork seas appear a world of natural elements and abstract forms: fish, flowers, wavy lines, spirals, moons, stars, rays of light flashing. Hearts pulse, waves ripple, birds chirp. A red scorpion-like creature crawls while a blue bird confronts a disembodied head, lips open like a classical bust awakening. Clouds, a lemon, and loaves of bread intersect columns of straight, squiggly, and diagonal lines. There are eggs, pebbles, the letter X. A pseudo-inscription in the upper right-hand corner feigns Arabic text. Amine’s forms wander freely in a poetic space animated by scenery drawn from cherished gardens and landscapes. Playful yet controlled, the pieces submit to their tightly organized woven environs. The three tapestries were signed El Bacha and dated 1984 and 1985. They do not appear to have titles. Amine and Antoine might have referred to each work in progress by a name or certain characteristic when speaking to each other, but their descriptors are unknown to us.

During the long hours of collaborative making, Amine and Antoine developed a close affinity for one another. Amine visited Antoine frequently to see and discuss the weaving process. Conversations about their project morphed into wider ones that reinforced their friendship and solidarity.40 Amine’s daughter Mahita remembers “the energy of that moment, the room, the tapestry that took over the whole [space] […] it was very big, an installation.”41 Her father would sometimes take her to see the progress. Although she was a child at the time, the convivial and contemplative atmosphere left a deep impression on her, as she recounted, “It wasn’t just the artistry; there was more to it. They were aligned philosophically, politically. Antoine really listened [to my father]; he was a very good listener. I think my Dad felt comfortable around him. It was a harmonious relationship.”42 Their slow method of working reflected a growing kinship, an allowance for the other’s pace. “I remember there was real conversation, rich conversations during the weaving process, a bonding.”43 The tapestries, she remarked, were not a rendition, a lifeless reproduction of a painting, but imbued with “the soul” of each creator.

As Mahita noted, Amine painted similar imagery prior to the war, reflecting a stylistic and thematic continuity.44 Antoine, in the Zouk tradition, had previously woven abstract and vegetal motifs: rosebuds, cats, crosses, butterflies, boats, curling tendrils, leaves, and triangles scattered across pillows, abayas, the toes of slippers. Amine’s controlled compositions of whimsical objects and creatures enliven their plain-woven structure and suited their translation. Undertaken in a spirit of mutual appreciation, the project renders incongruous externally imposed hierarchies surrounding tapestry and degrees of creativity while illuminating the transformative possibilities of cartoon-making. The friendship, fuelled by a sustained adherence to aesthetic beauty and tolerance, offers a story of connectivity that transcends artistic boundaries; it moves beyond questions of attribution and the division of labour to foreground practices of bonding and interdependence.

The ties forged by Antoine and Amine exhibit an intentionality, a mode of working and living, an upholding of social values during a protracted war. Not only do the weavings materialize a stylistic synergy and aesthetic sensibility, but they also express shared commitments. To Amine, an important aspect of seeing, of understanding a painting (or other work of art), was to like it.45 He wished for his audiences to feel joy, a sense of vitality and lyrical wonder. It seems probable that he, too, felt, and indeed created, joyfulness when he visited Antoine to observe the weaving of his designs, and when he brought his young daughter to watch their animated discussions at the loom.46 It would have been a festive occasion when, toward the end of the process, Antoine meticulously tied the ends of the warp before cutting it, when he unrolled the tapestry from the wooden beam to reveal the whole for the first time. A sense of fulfilment may have infused the two makers as they remarked upon the finished colours and textures of their work, as they acknowledged a continuation and expansion of their artistic practices, as makers, teachers, and neighbours.

Amazingly, we have incredible memories from our time during the war. When East and West Beirut were split, we would go on picnics with friends as a form of resistance. We would drive to the Green Line, park, cross the border, meet our friends in Achrafieh, drive up with them to the north and have a picnic. It was like there was no war. Time felt suspended. We would then cross the Green Line with a suntan, a few new paintings by Dad, a bunch of wildflowers and many great memories. There are a lot of ‘picnic drawings’ that he made.47

Amine and Antoine’s collaboration is one striking example of the highly creative patterns of social and ecological connection in the 1980s. Alongside visits to Antoine’s studio, Amine’s daughter Mahita retains joyous memories of picnics with her father, which she describes as a deliberate curation of beauty by her parents and family friends. They cultivated a rich sensorial relation between art and life in and beyond the studio and loom space. The families’ culinary activities, social gatherings, nature walks, and gardening reveal an interconnected form of artistry that infuses meaning into the vibrant imagery of the three tapestries and their collaborative making.

Mahita recalls the care and attentiveness shown by Amine and her family members when together they embarked on the lengthy process of cooking and preparing food, assiduously wrapping and packaging their cherished bundles. “We would cross two different borders and checkpoints […] walking, while carrying the most complicated cakes and tarts.”48 Their sense of delight at their creative autonomy emerged with these extensive joint preparations, taken before arriving in the forested areas. Once there, they would spread blankets and share elaborate meals with close friends.49 Mahita collected wildflowers and listened to birds, which Amine rendered (fig. 10). While the physical movement was not without risk and at times could be stressful, the communal effort and energy restored a sense of balance. Back at home, Angelina, too, would maintain a lush plant-filled terrace despite its precarious position overlooking the Green Line, which rendered the balcony garden vulnerable to snipers. Even when the family sheltered in the lowest part of the building, Angelina would ascend to water the delicate leaves and potted roots, tending the botanical sanctuary of Amine’s compositions. “In the midst of chaos, they [Amine and Angelina] would do their own thing,” or, in other words, they would “curate moments of beauty and connection, joy and delicacy.”50

This convergence of, and reverence for, artistry and nurturance are reminiscent of the looms that Antoine crafted, transported, and maintained. He and Saada set aside bones from family meals to clean, carve, and integrate for sustained tension and flexibility, a custom to which Saada adhered after his death. Returning to the rhythmic sway of the heddle bar, Saada preserves a shared and embodied practice. These memories and touchstones draw attention to less visible systems of care and interdependence, in which Antoine and Amine participated and which they valued so deeply. “That’s the trace,” Mahita says of their collective efforts, “the impact left with me.”51

In The Promise of Happiness, cultural theorist Sara Ahmed writes, “We are moved by things. In being moved, we make things.”52 She elucidates that an object can be affective “by virtue of its own location” and “the timing of its appearance,” and that to “experience an object as being affective or sensational is to be directed not only toward an object but to what is around that object, which includes what is behind the object, the conditions of its arrival (emphasis added).”53 Through this lens we might perceive the affective value of bones attached to a wooden loom and the tracings of lines and numbers on paper, and to reflect on what is behind and around the rainbow-coloured chain of fibre samples, which compose the three tapestries with their pulsing hearts and harmonious creatures, the flickering stars and suns that refuse to be blotted out.

Such charge resonates with the words of artist Paul Wakim, whose recollection of weaving and war drew forth a vibrant world of associative flashes. In the late 1970s, Paul brought his work to the forests of the Matn (Mount Lebanon). He had moved his atelier to the town of Baabdat, where he transported various materials and tools, including one of three looms he had built near the Damour river in Jisr el Kadi.54 Surrounded by trees and branches, he felt attuned to the sensorial and kinetic processes of loom-making and fibre preparation. He also applied this artistry to repairing household objects. Different looms and frames for furniture could be carved from different types of wood, he recounted, each emitting a characteristic scent.55 On long nature walks he gathered branches for use as materials.

Paul describes the project of constructing a loom and repairing a chair as a kind of poetic and temporal journey, “I took pleasure in stretching raw linen threads, in lining a structure with pine branches […] The wood and the weaving mixed, in two and three dimensions.”56 Natural materials, in turn, activated memory, reconnecting the artist with distant places, activities, and people, “When the wood is fragrant, the bond is stronger, especially juniper cade […] the scent is so deep and takes me back to my childhood.”57 These scents prompted him to reimagine the balls of wool knit by his sister and mother, and the village fishermen mending nets. He also pictured, “the kites that I made, with reeds, coloured leaves and cotton yarn, balls rolled up on the stick held by both hands […] as well as spinning tops thrown with thick cotton thread, the crosses of the chain […] putting on my buttons of my linen jackets, which I sewed with the help of my sister.”58

Perhaps, as Nicolas Moufarrège elucidated, the making of a tapestry is about creating “a kind of balance” between the hand and the brain, between individuals, extending to “even the inner compartments of a person.”59 Its processes engendered new relationships, facilitating the forging (and repairing) of bonds in a changed environment. They also continue to elicit strong, tactile memories, enacting a form of recovery and cultural preservation. As conveyed in the different settings of retelling, creators placed weight on connectivity, on processes of making and becoming, and on restoring a sense of balance, rather than on finished or autonomous pieces.60 Social and ecological connection assumed multiple, layered forms through processes of making and recollection. In addition to those forged in real time, the slow preparation of cartoons, looms, and fibres strengthen, in perpetuity, bonds across temporalities. Tapestry, in form, movement, and memory, endured Lebanon’s civil war as a constructive practice, leaving its multisensorial imprints as testimony.

I thank Nadia von Maltzahn for her support of my research and feedback on this article, the two anonymous peer reviewers for their suggestions, and Marika Takanishi Knowles and colleagues from the Creative Writing workshop at the University of St Andrews.

Abisaab, Malek, and Michelle Hartman. Women’s War Stories: The Lebanese Civil War, Women’s Labor, and the Creative Arts. New York: Syracuse University Press, 2022.

Ahmed, Sara. The Promise of Happiness. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2010.

Audi, Tony. Personal communication, June 2018.

Auther, Elissa. “Classification and Its Consequences: The Case of ‘Fiber Art’.” American Art 16, no. 3 (2002): 2–9.

Ayad, Myrna. “Remembering Amine El Bacha.” The National, 19 May 2020.

Bellan, Monique. “Ruptures and Continuities: Lebanon’s Art Galleries in the 1980s with a Focus on Galerie Damo (1977–88).” Manazir Journal 7 (2025): 21–56. https://doi.org/10.36950/manazir.2025.7.2.

Bryan-Wilson, Julia. Fray: Art and Textile Politics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017.

Constantine, Mildred, and Jack Lenor Larsen. Beyond Craft: The Art Fabric. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1972.

Cotton, Giselle Eberhard. “The Lausanne International Tapestry Biennials (1962–1996): The Pivotal Role of a Swiss City in the ‘New Tapestry’ Movement in Eastern Europe after World War II.” Textile and Politics: Society of America 13th Biennial Symposium Proceedings, Washington, DC, 18–22 September 2012, Paper 670. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf/670.

Dossier of Dale Egee, application to the ninth Lausanne Biennale, archives of the Fondation Toms Pauli.

Dossier of Nicolas Moufarrège, application to the ninth Lausanne Biennale, archives of the Fondation Toms Pauli.

El Bacha, Angelina. Personal communication, June 2022.

El Bacha Urieta, Mahita. Personal communication, May and September 2025.

El Hani, Sanaa. Personal communication, June–August 2022.

Farge, Arlette. The Allure of the Archives. Montrouge: Éditions du Seuil, 1989. Reprint, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2013.

Fitchett, Joseph. Amine El Bacha. Beirut: Contact Art Gallery, 1972.

Gerschultz, Jessica. Decorative Arts of the Tunisian École: Fabrications of Modernism, Gender, and Power. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2019.

Gerschultz, Jessica. “Notes on Tending Feminist Methodologies.” In Under the Skin: Feminist Art and Art Histories from the Middle East and North Africa Today, edited by Ceren Özpinar and Mary Healy, 131–43. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020.

Hakim, Victor. “Marian Claydon et Nicolas Mufarrij: A la Galerie ‘Triad Condas International’.” La Revue du Liban, 1973, 76.

Hashem, Saada. Personal communication, August 2022.

Junet, Magali, and Giselle Eberhard Cotton, eds. The Lausanne Biennials, 1962–1995: From Tapestry to Fiber Art. Milan: Skira and Lausanne: Fondation Toms Pauli, 2017.

Kang, Cindy, ed. Marie Cuttoli: The Modern Thread from Miró to Man Ray. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2020.

Kikoler, Jennifer, ed. Nicolas Moufarrège: Recognize My Sign. Houston: Contemporary Arts Museum, 2018. Catalogue of an exhibition held at the Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston, 10 November 2018–17 February 2019 / Queens Museum, Queens, 6 October 2019–17 February 2020. https://issuu.com/thecamh/docs/moufarrege_pages.

Kuenzi, André. La nouvelle tapisserie. Geneva: Les Éditions de Bonvent, 1973.

Lurçat, Jean. Designing Tapestry: Fifty-Three Examples Both Antique and Modern Chosen by the Author. London: Rockliff, 1950.

Maltzahn, Nadia von. “Introduction: Lebanon’s Visual Arts in the 1980s Defying the Violence.” Manazir Journal 7 (2025): 2–19. https://doi.org/10.36950/manazir.2025.7.1.

Malusardi, Flavia. “The House Stands Tall: The Social Dimension of Dar el Fan and Janine Rubeiz’s Curatorial Activities during the Civil War in Lebanon.” Manazir Journal 7 (2025): 83–107. https://doi.org/10.36950/manazir .2025.7.4.

Miles, Tiya. All That She Carried: The Journey of Ashley’s Sack, a Black Family Keepsake. New York: Random House, 2021.

Obeid, Michelle. “Friendship, Kinship, and Sociality in a Lebanese Town.” In The Ways of Friendship: Anthropological Perspectives, edited by Amit Desai and Evan Killick, 93–113. New York and Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2010.

Özpinar, Ceren. Art, Feminism, and Community: Feminist Art Histories from Turkey, 1973–1998. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2024.

Radi, Nuha al-. Baghdad Diaries: 1991–2002. New York: Saqi, 2003.

Saadé, Salim. Personal communication, June 2018.

Sultan, Fayçal. “Amine El Bacha: Memory in the Palm of His Hands.” In Partitions and Colors: Homage to Amine El Bacha, 15 September 2017–12 March 2018. Beirut: Sursock Museum, 2017, 5–11. Catalogue of an exhibition held in the Library and Archives of the Sursock Museum, Beirut, 15 September 2017–12 March 2018.

Wakim, Paul. Personal communication, March 2022.

Weigert, Roger-Armand. French Tapestry. London: Faber and Faber, 1962.

Wells, K. L. H. Weaving Modernism: Postwar Tapestry between Paris and New York. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2019.