This article examines the artistic practice of Lebanese painter Fadi Barrage (1939–88), focusing on the late 1970s and early 1980s, a period marked by his displacement during the Lebanese Civil War and his subsequent exile in Athens. Drawing on an intimate archive of unpublished diaries, sketches, and personal correspondence, the article explores how Barrage’s paintings functioned as both a refuge and a reflective process for navigating trauma, memory, and marginalization. Rather than depicting war-induced violence and desire directly in his paintings, Barrage developed a deeply personal visual language rooted in abstraction, which he referred to as “paint-feeling”—emotive compositions that concealed often erotic and affective content beneath layers of texture and form. Central to the discussion is Barrage’s conceptualization of “Fleisseh,” a term drawn from his childhood that came to denote both a real and imagined space of emotional safety, creative freedom, and queer desire. By engaging with Jill Bennett’s theory of empathic vision and Kirsten Scheid’s concept of taswir, the article situates Barrage’s practice within broader debates on representing trauma and the interactive creation of meaning through image-making. His paintings offer insight into how experiences of violence and queer desire are encoded in visual form, particularly when open expression is constrained by social or political contexts. This article brings new attention to an overlooked modernist trajectory in Lebanon, showing how Barrage’s personal notes and sketches reveal the ways artistic practice can serve as a means of emotional survival and a process for transforming trauma, displacement, and marginalization into an affective visual language.

Exile, Fadi Barrage, Taswir (Image-Making), Art and War, Queer Abstraction

This article was received on 5 August 2025, double-blind peer-reviewed, and published on 17 December 2025 as part of Manazir Journal vol. 7 (2025): “Defying the Violence: Lebanon’s Visual Arts in the 1980s” edited by Nadia von Maltzahn.

Better, after many days or weeks of restlessness, liquor, changes of weather, sleeplessness, heat, cold, misery. And the necessity to think things out in painting. Has it all borne fruit finally? I seem if not quite settled, settling, down to some approach to things, to the materials, the manner, the matter of my life, by which I can explore & develop myself & my work with a modicum of serenity.1

Thus writes Lebanese artist Fadi Barrage (1939–88) in his diary entry of early October 1982 in Athens, where he had found some kind of peace after a number of restless years following the destruction of his studio in Downtown Beirut in the early phase of the Lebanese Civil War seven years earlier.2 It was to be short-lived, as he was forced to leave Greece in 1985 and sailed to Cyprus. Weakened by illness, in mid-1987 he returned to Lebanon, where he died on 26 January the next year. Drawing on the artist’s diary entries and notes from the late 1970s and early 1980s, drawings, sketches, and an unpublished manuscript by one of his friends, this article explores how the context of exile and precarity affected Barrage’s artistic production, and to what extent Lebanon and the early stages of war he witnessed continued to be present in his work and thinking.3

“To think things out in painting” infers a direct relationship between the subjects preoccupying the painter and what he expresses through the medium of paint. Barrage was confronted with societal pressures throughout his life, not least due to being gay, and painting for him became a kind of refuge. It was a process through which he came to terms with reality—not through straightforward depiction, but through the material and affective possibilities of abstraction. As Jill Bennett has argued, visual art that engages with trauma or marginalization does not necessarily represent these experiences directly. Instead, it can work through affective resonance, evoking what remains unspoken or incomprehensible. Barrage’s painting practice aligns with what Bennett calls empathic vision: an approach that allows trauma and memory to emerge through texture, form, and material rather than through explicit content.4 Significantly, Barrage creates space to explore affective experience and interpretation, which speaks to Kirsten Scheid’s notion of taswir, or the interactive creation of meaning through image-making, where the “sura [image] demands interaction to form into visions not otherwise seen.”5

“To think things out in painting” thus captures how painting became a reflective process for navigating personal precarity, memories of violence and love, and social marginalization. The article traces Barrage’s journey from Beirut to Athens, highlighting the influence of war-induced trauma, physical displacement, and precarity on his work. A key focus is his development of “Fleisseh,” a term derived from the name of his high-school boarding house denoting both a real place from his youth and a conceptual framework for abstract expression. Fleisseh works embody what Barrage called “paint-feelings,” emotional compositions that concealed often erotic content under layers of abstraction. This strategy of visual masking aligns with queer artistic practices, offering protection and layered meaning in a hostile social environment. The article foregrounds Bennett’s theory of empathy and Scheid’s notion of taswir as guiding frameworks for understanding his artistic responses to trauma, exile and marginalization, while recognizing that there is much room for future readings.6

Having access to the artist’s diaries and notes is a great privilege and opens up new ways to understand his art. For Barrage, writing was a way to structure his thinking; he was “not interested in the product” of his notes as such; “someone else, my hapless biographer to whom I hereby apologize for the tortuous ways, will use them,” he writes in May 1984.7 In this article, I take on part of that challenge. Bringing out the voice of the artist allows us to draw connections between his ideas, thoughts, the social environment and artistic production, and get a sense of the reality of living in war-imposed exile while drawing on memories. It also enables us to map out the artistic trajectory of an artist who to date is little understood.

Fadi Barrage was born in Beirut as the eldest child of Bashir Barrage, a grain merchant who lived a comfortable life until faced with bankruptcy. Barrage had a complicated relationship with his father, and after completing high school as a boarder at Brummana High School, a British Quaker school in Mount Lebanon, and working for a brief period in the family business, he left to the United States to study classics at the University of Chicago in the early 1960s.8 This was followed by three to four years in Paris, where he allegedly turned night into day and enjoyed his freedom with his friend the artist Georges Doche (1940–2018). He returned to Beirut in June 1967, but left again intermittently before settling in his hometown in November 1968 after the death of his father.9 He had his first two solo exhibitions at L’Orient, one of the main Lebanese daily newspapers whose headquarters also served as an active exhibition space at the time, in March 1968 and February 1971.10 In 1972 he exhibited at Dar El Fan, a vibrant member-run cultural space founded by cultural activist Janine Rubeiz.11

In April that year, he left his family’s house where he had been living with his mother, and moved into an apartment in Bab Idriss, the commercial centre of the city which was lively during the day and quiet at night, as few people actually lived there. As Barrage’s friend, the writer Soraya Antonius, notes,

one of the owners of the [building] was a close friend and rented him the flat on a basis of friendship; it was the first place of his own in Beirut and he was ecstatic about his freedom. […] He was probably the happiest soul alive in that richly self-satisfied town. There were problems occasionally, caused by his way of life, but perhaps the brief periods of fear accentuated pleasure. At any rate, this was a golden age. Hard work, productive; exhibitions, visits from buyers and critics; pleasant living, friends, lovers, adventures. He believed he was laying the foundations for a life of some success in his work, spinning a web of future strength.12

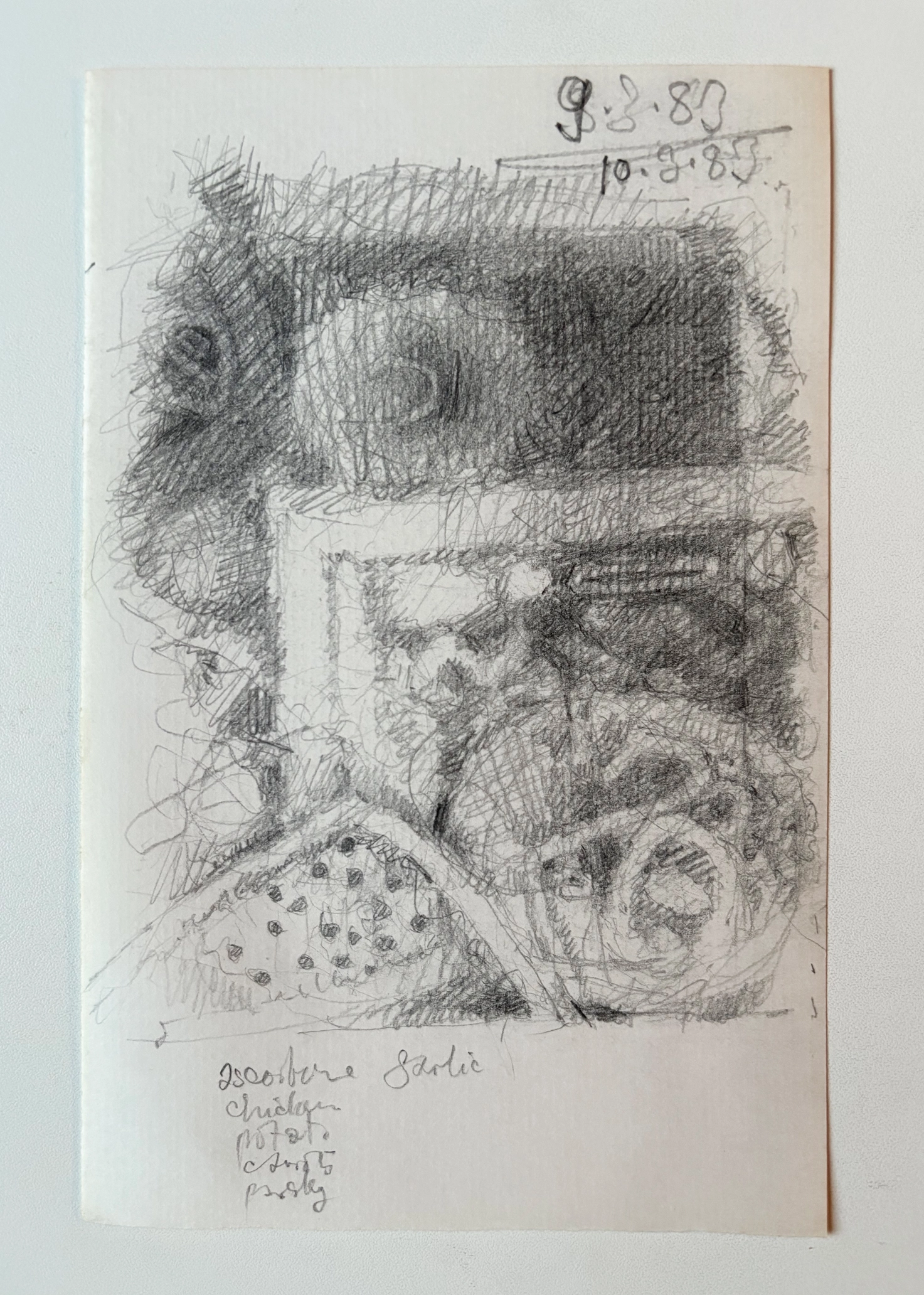

“His way of life” refers to living out his homosexuality in a traditional society, where there was no easy path to follow.13 Barrage seemed to have found his way to navigate this life, however. After leaving Lebanon, he frequently referred back to his happy days in Bab Idriss, and an allusion to elements of his apartment are found in his drawings and paintings. In a sketch of August 1982, he studied the railing of his house in Bab Idriss (fig. 1), for instance, and later that year drew an abstraction referencing his kitchen there. The railing, drawn just after Beirut had been intensively bombed by the Israeli army in the summer of 1982 to force the eviction of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), is a tool to protect, but it also separates. The particular shape of this railing evokes a penetration, which can be read in both an erotic and a war context. The same day of the sketch, he writes in his diary: “P.L.O. beginning pullout of Beirut this morning. I am tired, tired. I don’t think I will ever go back there.”14 Tainted by memories of war, he continued dreaming of Bab Idriss as a refuge, however, “where [he] would discover in the ruined passages and moulderly remains a set of sunny rooms hidden from war, secret and all [his] own.”15

His last solo exhibition before leaving Beirut took place at the gallery Modulart in March 1975, just a month before the formal outbreak of the Lebanese Civil War. Art critic Dorothy Parramore Eggerickx, a close friend of Barrage, starts her review of this exhibition with the following observation:

As Fadi Barrage was explaining his work to me, I couldn’t help regretting that he is the only painter I have known in years who could do so in such a lucid manner. That is because Barrage, besides being an original and totally dedicated painter, is an intellectual with a difference. The Camus definition of an intellectual holds for Barrage: the man who is simply more interested in ideas than anything else.16

This observation is confirmed in the artist’s diary entries, in which his dedication to his art as well as his reflections on his approach to it are well articulated. He writes in February 1979, for example, that he “must distance himself from the visual approach and go more towards a mental one. Only in that way can [he] really paint everything, like [his] balcony in Bab Idriss, the bed with scrambled sheets, light, the sniper, Jamal.”17

His approach to painting revolved more around an idea rather than something concrete. “This is the interest of this sort of painting and drawing whereby no longer a formal translation of an object as in cubism, but a graphic informal swift ‘unpremeditated’ strike at an idea, a feeling, a mood, through an object, and beyond it.”18 This emphasis on capturing feelings and moods through abstraction resonates with Bennett’s theorization of art’s capacity to evoke trauma and affect. As she argues, such art does not offer straightforward representation, but instead invites an empathetic engagement through sensory and emotional registers that gesture toward experiences often too complex or painful to depict directly.19 In this vein, let us turn to how Barrage experienced and processed the early phase of the civil war.

In October 1975, the fighting that had started in different locations in Lebanon earlier that year reached Bab Idriss. Downtown Beirut was especially affected by the initial phase of the war, the so-called two-year war.20 Barrage had to leave his apartment, and after attempting to return, he was evacuated during the second round of fighting there later that year. When he revisited Bab Idriss briefly in the spring of 1976, he found his studio pillaged and destroyed.21 During this time, he rented a small place in the West Beirut quarter of Raouché. The violence he experienced first-hand did not leave him indifferent. On 30 December 1975 he writes:

The only way to paint all, throat-slitting in Bab-Edriss22 & all. What I have to say, what has to be said, what has to come through one day before it chokes, the horror of a sunny afternoon in Bab-Edriss when three young men rang my downstairs bell asking who lives here.

The boy in the hands of a sick man, a maniac, who had lowered him naked into an empty bathtub, his hands tied behind his back.

Kill something not only sentient, but aware & responsive. Kill your own kind.

Their war is bloodier than they realize. What has to come through itself makes the idiom, modifies the language well-rehearsed to the message. Colour tempera, transparent & opaque, colour not line.23

His repulsion at the war comes out clearly, as does Barrage’s distancing itself from it; it is “their” war. The deep impact the brutality of violence committed during the war has had on him can be strongly felt; it is almost as though Barrage chokes while writing these lines. The references to the “throat-slitting” and “the boy in the hands of a sick man” refer to a scene of torture he witnessed, and that he describes in gruesome detail in a rough undated diary entry in February 1976, preceded by a pragmatic “same action and texture as in the small torture paintings.”24 The scene as described in this later entry has a clear homophobic dimension to it, which must have accentuated its traumatic effect on Barrage. His reflection on how to digest through his work what he has been witnessing and suffering—the “horror of a sunny afternoon in Bab-Edriss”—, as well as on the method of representation—“what has to come through itself makes the idiom”—indicates an acute awareness of how artistic language must adapt to convey trauma and violence. Painting through idiom is shaped by the emotional weight of the subject matter, resisting literal depiction.

War motifs preoccupied him for a couple of years, not continually but periodically. The 1976 massacre of Tall al-Za‘tar, in which Palestinian civilians were killed by Christian militia after a months-long siege, was one of the themes he treated when already living in Athens.25 Barrage had left Beirut in July 1976, first moving to Alexandria (July–October 1976), then Istanbul (October 1976–January 1977), before settling in Athens in January 1977. Early notes from Greece reveal his struggle to depict such scenes:

Woman running forward, screaming, two children in her arms, one of them looking straight at me, terrified, photograph Tall al-Zaatar, how to paint this without sentimentality, or bravura, or too much detail, merely a hint of horror and tragedy.26

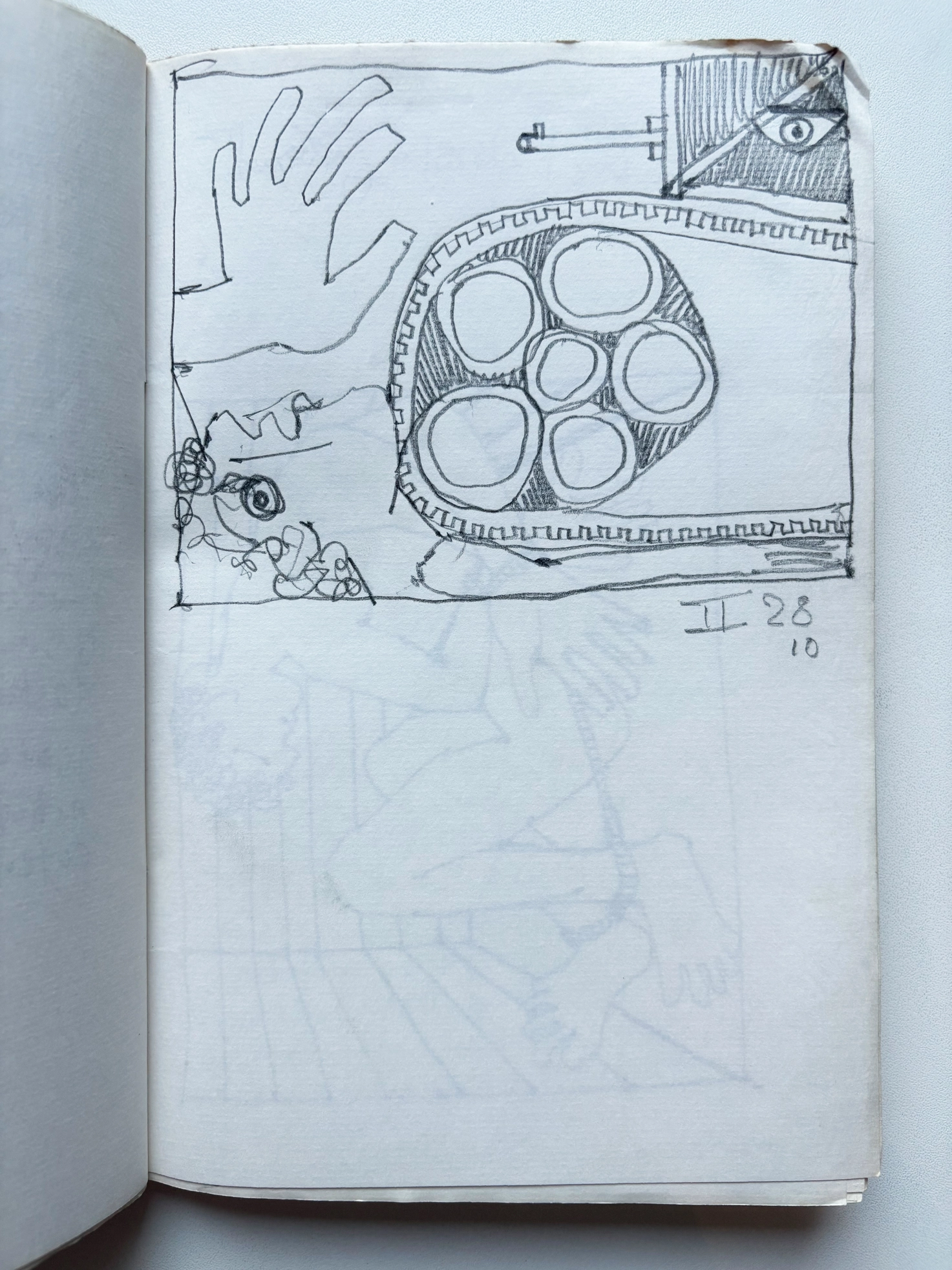

In his diary, Barrage described recurring symbols—in an entry he labelled as “frames for different portions of an idea” (fig. 2)—such as cupboards, mirrors, jars, niches or refuges. The entry includes ones specific to the experience of war, such as “barbed wire” and “wedge as war engine.” He writes about another sketch of the same day (fig. 3):

1/4 sheet of Schoeller of this, reduced to the simplest: warrior’s face an archaic Greek helmet, her hand much less imperious, more helpless, her expression too. Very satisfactory combination of ‘abstract’ triangle wedge and helmet with the good realism of the mother & child.27

In this pencil drawing composed of overlapping profiles and structural divisions, the gridded format serves as both framing and fragmentation. The central figure that fills three quarters of the overall frame, the mother with child, comes across as both vulnerable and assertive, trying to protect her child by raising her oversized hand. The multiple rectangles the mother and child are placed in can be read as a niche or refuge, as decoded in fig. 2, while the wedge containing the warriors is described as a war engine. There is a tension between the geometric rigidity of the grid and the profiles of the two warriors on the one hand, and on the other the emotive mother clutching her child, which started to become more abstract. This interplay between form and subject suggests how empathy can be embedded in art: the drawing does not simply illustrate suffering but evokes the emotional textures of vulnerability and protection, inviting viewers into an affective encounter rather than a straightforward narrative.

Barrage was deeply concerned with translating his more figurative drawings into abstract paintings. He believed figuration worked best in drawings or in small format paintings, with the exception of portraits.28 Reflecting on the mother and child motif, he elaborates:

But I am wondering about one further step to take, in the direction of yet greater abstraction: Not merely abstraction in the sense of a simplification of the figure into a calligraphic design, but an abstraction further of this design into real uninhibited brushstrokes: I no longer mean what I used to do in Raouché, that is a strictly figurative idea worked to abstraction of brushwork & colour, but only a further abstraction into paint of a drawing already completely abstract […]. What would have happened in the case of this painting would be that the mother & child would have become less literal; possibly more powerful? This is the sort of thing I must try for this evening. And to begin with some very free drawings here (fig. 4).29

He distinguishes in his work between drawing and painting, the former often being well-rehearsed sketches that could then be transformed into much more spontaneous and experimental paintings.30 He wonders whether his depiction of the mother and child, by becoming less literal, would become more powerful. This again aligns with the idea that art engages viewers through affective cues that open space for emotional reflection.31

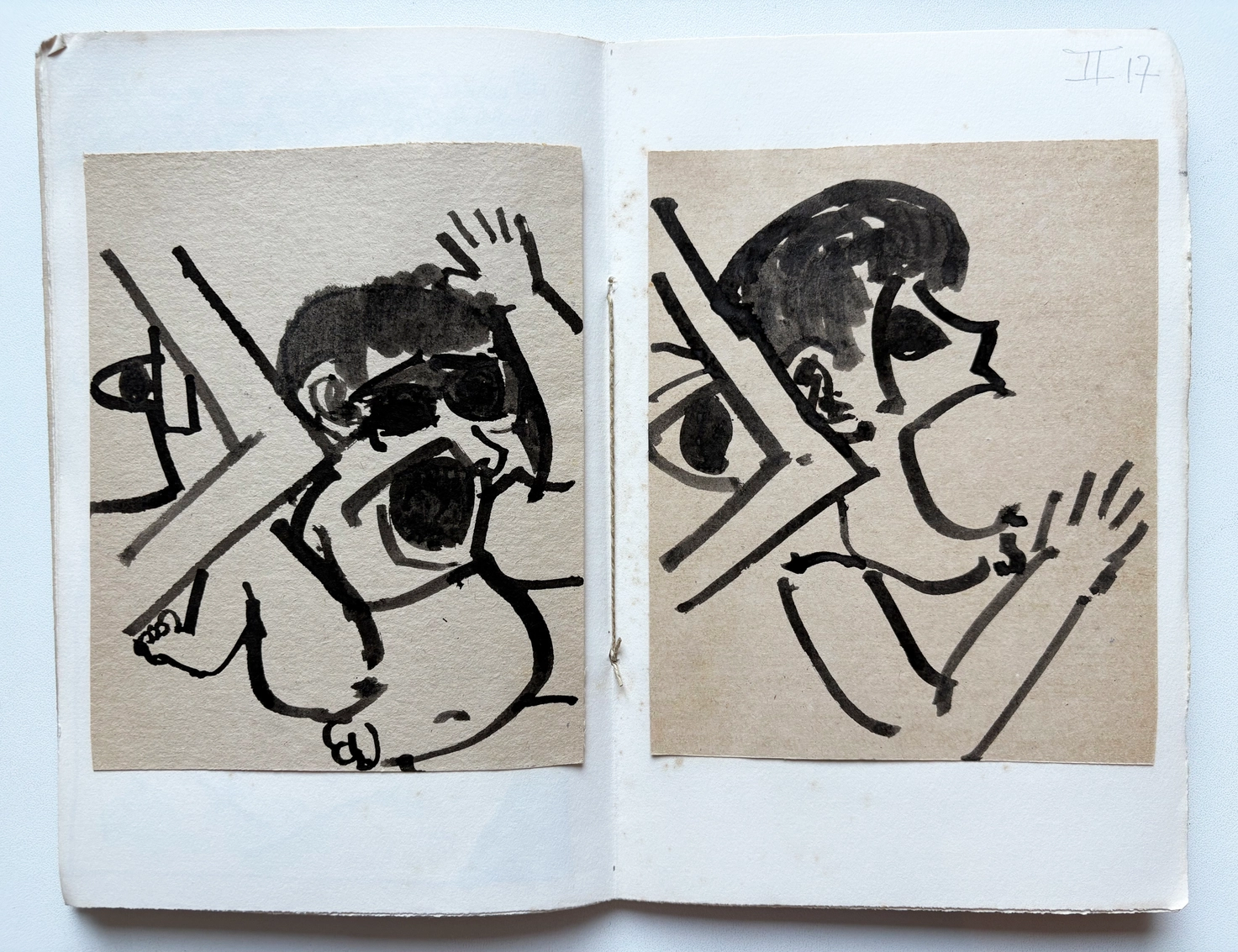

The last explicit war sketch I have seen in his diaries dates from February 1979, depicting a tank rolling over a hapless youth grasping for help (fig. 5).32 The same day, he sketched out some of his recurrent motifs, including feet, an abstracted garden, a sleeping boy. While he clearly followed what was happening in Lebanon, he always returned to his conviction that life, art, and goodness would prevail over destruction.33 He writes in 1978 that “the affirmation of life [was] more important than anything else. No attempt at all sorts of massacres, it is not necessary to destroy in this way, rather by stating the opposite, life, love, sleep.”34 In a series of studies on the sleeping boy (fig. 6), Barrage contemplated further on how his drawings would translate into paintings. I have focused on this practice elsewhere, arguing how Barrage’s work on the sleeper and figurative drawings of the male nude depended on how confident he felt in relation to his surroundings, in material, emotional and security terms.35

Landscapes were not one of his motifs, and he was explicit about differentiating his work from his peers in Lebanon who had turned to this genre during the war.36 The following passage from March 1979 reveals some of his deliberations about processing the war through painting in relation to the market and his peers:

And to hell with their drawing-rooms, mosaics of shimmering colour, soft transitions, blurred vague statements, mêlé-fondu, chassé-croisé and the rest. I could have done it if I had been a landscape-painter.

And I could make them now by giving them deliberately abstract paintings […], simply to paint without ever really attempting to depict or delineate the subject in any way […] letting it come forth if it can […] end up with absolute rubbish like everyone else’s ‘terres d’ombre’ and other shit.

Figures in a landscape, Fleisseh garden, water lilies!!

But:

if I were to think of Goya’s almost incomprehensible drawings, and proceed from there […]

horrors of war

ruins of Bab Idriss, ruin in general

no pretty colour

That might be paint as paint, and leave the other subjects for drawing.

Jamal in my bedroom for instance […]37

This passage highlights Barrage’s contempt for some of the work produced at the time primarily to satisfy market demands and decorate drawing rooms. His sarcastic dismissal of “mosaics of shimmering colour,” “soft transitions,” and “chassé-croisé” critiques the tendencies of painting that had become widespread in Lebanon’s commercial art scene during the war, where gallerists often sold decorative works. His suggestion that he could have made “them now by giving them deliberately abstract paintings” reads as a critical comment on artistic compromise. At the same time, the passage presents a deeper reflection on the representational capacity of painting itself. While he imagines “paint as paint,” stripped of “pretty colour,” painting for him holds the potential to engage with the horrors of war, but only if it resists both aestheticization and literal depiction. Figurative depictions are left for drawing. The idea of paint as paint is reinforced in a diary entry later that year:

If I am to be absolutely honest then paint must be just paint, with no attempt at ‘saying’ anything that can be said in any other way, or even thought in any other way, therefore I must have no thought in my head when approaching the canvas […] Any thought that will come through will be most necessarily a painter’s thought, not a novelist’s or poet [sic] or anything else.38

What he values is a form of visual language that is suggestive, materially grounded and “almost incomprehensible,” recalling the emotional ambiguity and affective force of Goya’s war drawings.39 Rather than depict ruins or bodies in explicit terms, painting becomes a space where the trauma of war might be registered indirectly, through texture, tone, and abstraction, allowing its presence to emerge through the medium itself. For Barrage, it comes back to a differentiation between painting and drawing, abstraction and figuration, which we will look into further now when analysing one of his main entry points to painting, what he refers to as Fleisseh.

Barrage turned to abstraction not only as a strategy for coping with trauma, but also as a means of safeguarding emotional and erotic content within his work. Central to this was the conceptual and affective method of Fleisseh. In a July 1979 letter to restorer and newly minted gallerist Antoine Fani, Barrage attempts a chronology in which he sketches out seven different “manners” of his work of the past fifteen years, moving between (1) rigorous figuration (“figuration linéaire très rigoureuse, très primitive”), (2) rigorous abstraction (“abstraction linéaire très rigoureuse”), (3) more nuanced abstraction (“Refuges etc. Abstraction linéaire plus nuancée”), (4) abstract calligraphy (“Peintures calligraphiques abstraites”), (5) abstract figuration (“Figurations ‘abstraites’”), (6) figures (“Figures (portraits, mangeurs d’olives, etc.)”), and (7) what he refers to as Fleisseh, a combination of (3) and (4) (“‘Fleisseh’, entre 3 et 4”). At the time of writing, he was practising manners (5), (6), and (7), Fleisseh being the only manner he practised throughout all fifteen years documented (1964–79).40 So what was Fleisseh?

Let us consider these selected passages from his diary:

Too now therefore Fleisseh, divisions, quarters of a city, rooms in a house, the refuge and finally now the Fleisseh garden […]

Tomorrow studies of the house for Fleisseh, maybe even individual studies for the different quarters. […]

And in Fleisseh Circe’s house there is a room with woven fabric on its stripes! […]

Remember sleeper with refuge and the “Socrates” with Fleisseh.41Some abstracts with room for free ‘figurative’ brushwork, Fleisseh, handwriting, ‘figures’ in a ‘refuge’ garden […] with the Fleisseh ‘flower beds’ and the room in the back of Teta’s [grandmother’s] garden where the ‘madwoman’ lived.42

Fleisseh the only subject for painting and now make the best of it

dark or clear, blood or sperm or saliva on the lips

But it must never be directly of Fleisseh, but in fact of anything else, set up in that context for contemplation.43

This last statement is important. There was a real Fleisseh: it was the name of his boarding house at Brummana High School, where he was sent age eleven. Unhappy at first, he settled down and grew to love the place.44 At times in his notes, Barrage referred to the “real” Fleisseh, which principally denoted the garden around the house (the Fleisseh flower beds, the Fleisseh garden as mentioned in the quotes above), sometimes the house itself (the “golden stones of the actual Fleisseh”45). But mainly Fleisseh stood in for a deeply felt emotion that was translated into largely abstract painting. It is, he writes, “not a theme, it is a process, a manner, an approach to something. It is not itself an object of meditation, except in very philosophical terms.”46 It was born out of a memory of Barrage’s boyhood in the real Fleisseh, connected to happiness, pure emotions, love, and some kind of gardens of paradise, “the secret garden.”47 He writes about one of his paintings in progress in April 1980:

the statement is there, a trifle hard and bare and unaccompanied (will remedy later) but there quite definitely. Turpentine marvellous dries almost instantly will use no other medium. This is true Fleisseh once again. All the way back beyond Bab-Idriss and Dar el Fan, to Paris and the first remembrance of Fleisseh, the image born out of a despair of happiness.48

He explained that “the starting point of Fleisseh was the pencil drawing of the garden at Fleisseh. Can all drawings begin as drawings of Fleisseh? As a paint-feeling? Objectified? Realized in figures? Or left as abstract musicality?”49 In this sketch (fig. 7), one can clearly see how the floor plan of the garden in Fleisseh structures the composition, which is then taken to a metaphorical level.

Fleisseh represented an idea. In March 1980 he had written about starting a canvas

with an exploration of Fleisseh, not other ‘ideas’ in mind, refuge, delight and even now the need to find a safe hiding-place at the heart of things, his breathing all through the night, my head on his chest, that, defined, lived-through again not in recollection merely but as the only way to really know or feel it, the actual event was too brief for such knowledge.50

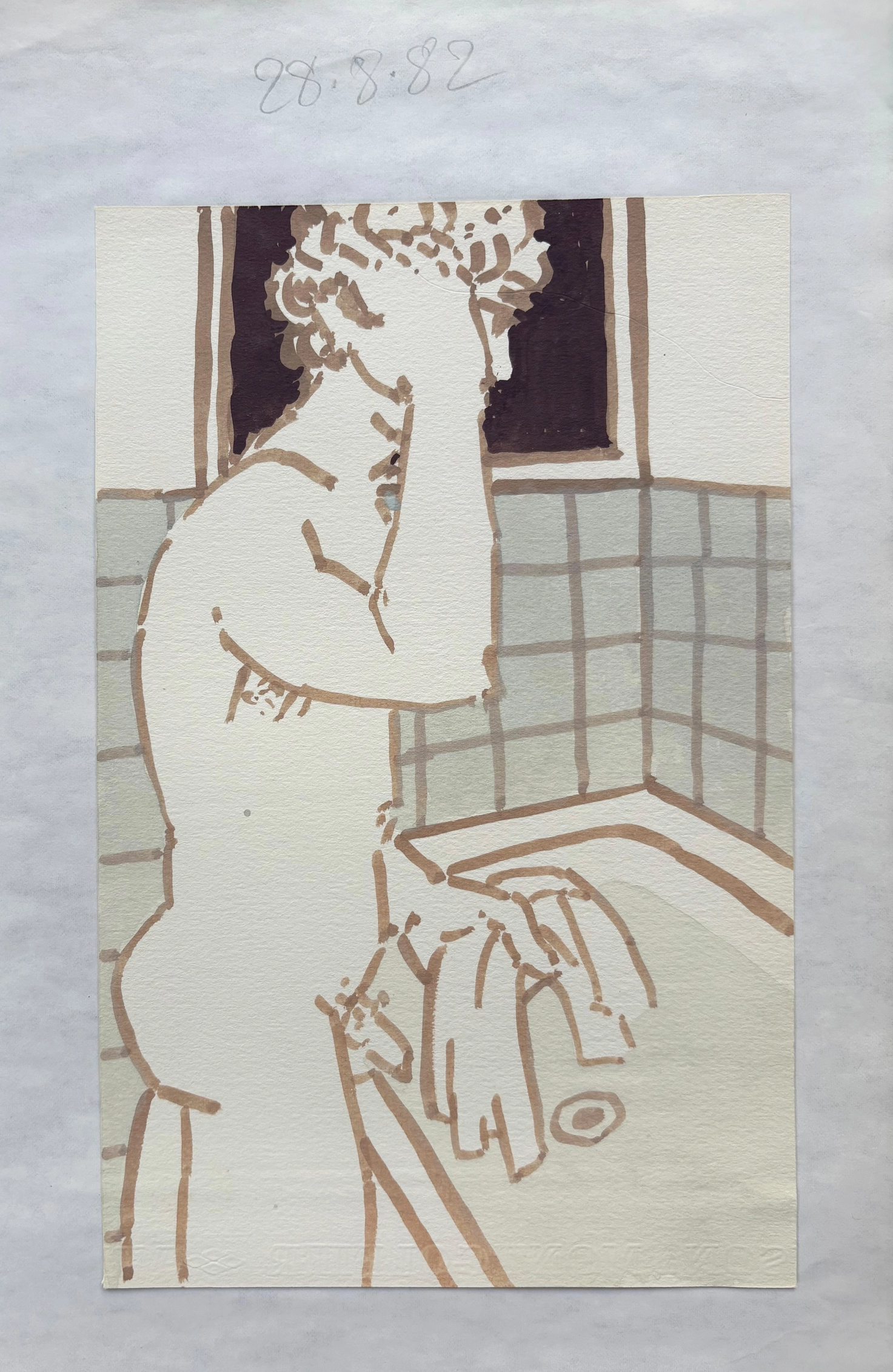

Fleisseh was thus also a refuge, a recurrent motif of Barrage.51 The perceived need for a safe hiding place was linked to being a gay man in the Eastern Mediterranean at the time, be it in Lebanon or Greece, in which he considered Fleisseh a small niche he had carved out for himself, a “precarious hideout.” He was deeply unhappy about not being able to find a “simpler happier relation between [his] work & life,” in which he did not have to take refuge in abstraction.52 Not feeling comfortable openly depicting male nudes in his painting, he looked for ways to mask or diversify his subjects. An example for diversification was to show men “through a cycle of their days,” such as when they bathed, dressed, or played billiards (fig. 8).53 While this diversification was expressed in figurative work, mostly small-scale, masking was done through abstraction. Masking one’s subject has been associated with queer tactics of camouflage, in which abstraction “both conjures new visualisations and rebuffs viewers’ impulses to recognize and categorize.”54

His Fleisseh works are clear examples of this masking, which worked more or less successfully. Barrage’s friend Ellen Sutton, in a letter to Soraya Antonius, describes the painting she acquired as follows:

Faadi’s Garden (my title for it […]) was roughly 18 × 24 inches. The colours were chiefly grey-green, non-blue pinks, browns, pinky-beige stones. It was not a representative painting. I saw a kind of building in the R-top, and L and centre-front ‘stones’. After a few days these stones became rather more suggestive of a part of buttocks and a phallus. The rest was a few tree trunks and foliage. It was the fact that I couldn’t see the picture without the anal sex which made me eventually part with it again. I had originally chosen it for its pleasing colours and composition in terms of mass + colour. The later specificity of some of these masses detracted from the picture (for me). F. did say it was the garden of his boyhood. (Perhaps he lost his innocence there?).55

After Sutton returned the painting to Barrage, he gave it to one of his lovers.56 Similar to “Faadi’s Garden,” this work (fig. 9a), which can also be seen behind Barrage in his studio (fig. 9b) gives a good idea about Fleisseh.57 While the erotic content cannot be overlooked anymore once one has seen it, it is suggestive enough to enjoy the painting for its composition, colour, and movement if one does not expect or look for any underlying motif. If Barrage’s war drawings asked how horror might be represented, Fleisseh asked how love and longing might be felt—and concealed—through the very material of paint.

Other than being a tool of masking, Barrage’s Fleisseh paintings thus represented a “paint-feeling.” He writes in April 1980:

Later, fascinating seeing, guessing, doubting, supposing, half-seeing what is continually hidden and revealed, provided it never becomes a sort of striving for a form of anatomical accuracy, to maintain it at the level of feeling, even at the cost of not communicating anything directly, the passion to see is enough.58

Barrage initiated an image, which depended upon the viewer to be completed. He thus consciously wanted to prompt imaginal striving in the sense of Kirsten Scheid’s notion of taswir (image-making), which keeps us in the interaction between an entity’s coming into being and becoming meaningful.59 As Barrage writes in December 1982:

[A]lways begin with an image of some kind, and, since the paintings are not going to be elegant ‘unfinished’ sketches anymore, I can modify, obliterate, rediscover it in the process of work. The composition will be more interesting if based upon an image, more discovery. Let the image conceal and reveal itself.60

And in the same vein three months earlier:

[T]wo days working on tiny watercolour on R.W. of reclining nude, cushions, ornate divan, testing out theories: it works perfectly, except that the conception of this nude is too obvious. Rather more mystery, little showing, no face necessary, brushwork more free. This was juvenile + ambitious. Abstracts too, with a definite intention. I mean a definite emotional content, Fleisseh usually.61

While Barrage’s drawings are worked out in detail, his paintings had to be free, suggesting their content without stressing the image.62

Taswir according to Scheid is an interactive process, “actively molding sense perception into social meaning. It invites the audience to undertake imagining so as to reach an emotional state and achieve cognizance of otherwise removed, banished, or disappeared events with full awareness of the horror, anger, or shame to be aroused.”63 Scheid gives the example of Jean Debs’s famine sculptures exhibited at the Beirut Industrial Fair in 1921. Barrage prompts an emotional response to his work, but for him this response is navigated not so much within a nation-building project, as in Scheid’s example, but rather within the space negotiated by a gay artist living in precarity, in a context where there was no civil rights movement and he had to test the lines.64 He thus reflects about one work in 1984: “removed the ‘penis’, it is still very much present without being there.”65

Barrage also refers to art as experience, speaking to the idea that an artwork is located within a network of making and reception. The interaction is intentional and reflected. He writes in September 1981:

So that it has taken about a month (very little less) to paint this ‘approach to Fleisseh’. I cannot any longer bear the strain of this type of improvisation, I must reintroduce a minimum of craftsmanship into my approach; ‘art’ may be ‘experience’, but preferably not as immediate as this. Some rehearsal of effects should probably enrich the experience, both at the stage of preparation in the study of choices & means and mood and manner, and in the final free performance in which it culminates.66

The audience is part of the process; Barrage thinks about the effect his works will have—also in material terms. About one series of abstract works in early 1979 he writes, “that is better for sales in Beirut, where they will only see colour,”67 implying that the viewers see what they want to see. Whether rooted in trauma, memory, or desire, Barrage’s paintings pursue an aesthetic of evocation rather than representation.

Beirut, and Lebanon more generally, were never far from Barrage’s mind. His stay in Greece was precarious, as it depended on his residency status being renewed every six months. In addition, he suffered from financial uncertainty, as he lived exclusively from the sale of his works, only at times supported by his brother who sent him money from Saudi Arabia where he was working. This precarity clearly affected his artistic production, as some works required a certain level of relaxation and feeling of security. As he ponders in 1980:

How do you paint when you’re insecure? Not, certainly, in the leisurely fashion required by these figurative drawings.

Afternoon, took my first good walk since the 2nd of December, to the Acropagos. Athens glorious. Green everywhere, red of sunset on the ruins. When I leave here, I will have left everything behind. I am not departing from Dhour-Choueir again. Not this time. Never. I took leave of mountains & pine trees & childhood and goodness in 1959 or 60. Now twenty years later I have found them again.68

He had found happiness in Athens, but the uncertainty of how long he could stay there distressed him and comes up repeatedly in his diary entries. In 1984 he contemplated making up his mind to leave on his own freewill, before being told to do so. He wavered as to whether it made sense to return to Lebanon, primarily concerned about his productivity. One day he wondered, “Where shall I go to? Where shall I find colours, canvas, certainly not in Lebanon”; the next moment thinking “I would probably work better in Beirut, probably because of the dreadful atmosphere there,” continuing: “I am of there, after all, and in my most distress have thought of Fleisseh which (the place itself, no longer) is still there. And today I was thinking of […] Dhour Choueir.”69 He believed he could make more money in Lebanon, too, and felt his stay in Athens was drawing to a close. His reflections express a feeling of belonging, ambivalent though it was. Despite writing predominantly in English, a legacy of the Lebanese education system, and his war-imposed exile in Greece, he was firmly rooted in Lebanon.70 It is interesting to note that one of the factors that seemed to hold him back from returning to Lebanon was the uncertainty of being able to obtain the needed material to work, reminding us of the very concrete obstacles artists faced in 1980s Lebanon.

In September 1985, Barrage could no longer extend his stay in Athens, and left not for Lebanon but for the island of Cyprus. “They have finally caught in to what I was engaged in, corrupting the youth of Athens, and now am looking forward to do the same to the Cypriots,” he writes half-jokingly to his friend Marianna Perry in Greece.71 In two subsequent letters he reports he was working hard, and that he was “getting his teeth into Nicosia.”72 He ended up spending less than two years on the island, part of which in a sanatorium in the mountains suffering from severe tuberculosis (TB). As Soraya Antonius writes about her friend:

Ten days earlier [in late March 1987] he had learnt that TB was not all that was wrong with him, he was in a state of acute distress—and there was none of the counselling, the psychiatric support, that is widely offered in the West to help people through the immediate shock—on the contrary, he was alone, day after night, except for a few hours. His suffering was evident and there are no drawings for those ten days, then this recapitulation of happiness begins. [Quoting Barrage:] ‘[…] my coffee cup [in Bab-Idriss] handpainted with gross flowers in deep reds and strong greens […] the curtain material we used to have in our summer house ages ago […] this sort of image is the very stuff of happiness for me.’ […] The scenes shown seem not so much actual depictions of a, or various homes, as a distillation of their essences.73

A distillation of essence. This describes Fadi Barrage’s work very well. The essence of his boyhood, of simple happiness in Bab Idriss, of war countered by love, thinking things out in painting. Barrage returned to Beirut at the end of May 1987, where he died in January 1988.74 While he often noted fevers and wrote of feeling unwell during his time in Athens, it was only in Cyprus that he discovered he had AIDS, the shock of which comes out clearly in Antonius’s manuscript.75 At the time of his death, his work was part of the Kufa Gallery exhibition in London.76 The Sursock Museum, Beirut’s main museum of modern and contemporary art, dedicated a small section to him in their homage section of the fourteenth Salon d’Automne in 1988–89 (fig. 10).77

This article has explored how Fadi Barrage’s artistic practice in the late 1970s and early 1980s responded to memories of war and love, and to conditions of exile and personal precarity. Through a close reading of his diaries, sketches, and paintings, it has shown how abstraction functioned not only as a formal strategy but as a mode of negotiation, a way of working through emotional and social pressures. His concept of Fleisseh captures the convergence of feeling and artistic process. More than a thematic motif, Fleisseh became a recursive space, embodied, emotional, and sensorial, through which Barrage returned to early experiences of happiness and desire.

Barrage’s notion of “paint-feeling” blurs boundaries between figuration and abstraction, revealing and concealing. Concerning taswir, we might say that Barrage’s work not only invites the viewer into the interactive process of meaning-making, it also enacts this process upon the artist himself. The act of painting becomes a site of transformation, where memory is not only represented but relived. Empathic vision is thus a mode of artistic engagement in which affect is transmitted through the texture and material ambiguity of the work. Painting for Barrage was a way of feeling his way through loss and love, violence and vulnerability.

His work opens onto broader questions about how queer desire takes shape visually, especially in contexts where open articulation remains fraught or impossible. This is something to be further explored. His personal notes and sketches offer not only insight into a largely overlooked artistic trajectory in Lebanon, but also a case study in how artists create interior worlds of refuge in the face of external instability. His practice of processing the violence he witnessed during the Lebanese Civil War with a temporal delay and geographic distance echoes the wider practice of Lebanon’s visual artists at the time.78 By bringing Barrage’s voice into dialogue with his artistic production, this article has foregrounded the significance of personal archives in reconstructing art histories where little written analysis exists. It underlines the layered strategies through which artists like Barrage responded to violence, displacement and the socio-political conditions of Lebanon and the broader Mediterranean.

This research was conducted in the context of the research project Lebanon’s Art World at Home and Abroad (LAWHA), which has received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (Grant agreement No. 850760). I am grateful to the two peer reviewers and Jessica Gerschultz, whose thoughtful comments have greatly improved my work, as well as to the Manazir team.

Note: The principal sources of this essay are the personal diaries and notes of Fadi Barrage, which are in the possession of the author.

Abillama, Ziad. “L’homosexualité.” Femme Magazine, ca. 1995, 6–21.

Adnan, Etel. The Arab Apocalypse. Sausalito, CA: Post-Apollo, 1989.

A., Y. [Agémian, Yolande]. “Fadi Barrage.” Le Soir, March 1975 [exact date not available].

Akar, Mirèse. “Ce soir à L’Orient, vernissage de l’exposition Fadi Barrage: Un prince de la couleur.” L’Orient, 27 February 1968.

Antonius, Soraya. “The Day of Outside Education.” Alif: Journal of Comparative Poetics 20 (January 2000): 257–68.

Antonius, Soraya. Unpublished and undated manuscript on Fadi Barrage.

Arcache, Armand. Catalogue des œuvres pour la vente aux enchères le mardi 16 juin 1998 au profit de la société libanaise du SIDA. Beirut: Centre Culturel Français, 1998.

Barrage, Fadi. Diary Monday 15 December 1975. In the possession of the author.

Barrage, Fadi. Diary 478 [March 1978]. In the possession of the author.

Barrage, Fadi. Diary 79-I.31-II.6/7. In the possession of the author.

Barrage, Fadi. Diary 79-II.13-19. In the possession of the author.

Barrage, Fadi. Diary 79-II.19-23. In the possession of the author.

Barrage, Fadi. Diary 79-III.4. In the possession of the author.

Barrage, Fadi. Diary 1979-July-October-1-86. In the possession of the author.

Barrage, Fadi. Diary 1979-November-1980-March-87-132. In the possession of the author.

Barrage, Fadi. Diary Dec. 80-1981/20-11-80-6.2.81. In the possession of the author.

Barrage, Fadi. Diary 81-August-September. In the possession of the author.

Barrage, Fadi. Diary 1982-27 January-5 August. In the possession of the author.

Barrage, Fadi. Diary 82-VIII-Août. In the possession of the author.

Barrage, Fadi. Diary 82-IX-Sept. In the possession of the author.

Barrage, Fadi. Diary 82-X-XI-Oct.-Nov. In the possession of the author.

Barrage, Fadi. Diary 82-XII-Dec. In the possession of the author.

Barrage, Fadi. Diary 83-IV-April. In the possession of the author.

Bennett, Jill. Empathic Vision: Affect, Trauma, and Contemporary Art. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2005.

British Lebanese Association. Lebanon – The Artist’s View: 200 Years of Lebanese Painting. London: Quartet, 1989. Catalogue of an exhibition held at the Concours Gallery, Barbican Centre, London, 18 April–2 June 1989.

Clerck, Dima de, and Stephane Malsagne. Le Liban en guerre: De 1975 à nos jours. Paris: Gallimard, 2025.

“Fadi Barrage: Demain soir, ce sera sa deuxième expo à ‘L’Orient’.” L’Orient, 16 February 1971.

Fani, Antoine (@fani_antoine). “Lettre de Fadi Barrage à Antoine Fani, 29 juillet 1979.” Instagram, 30 January 2024, last accessed 23 May 2024. https://www.instagram.com/fani_antoine/.

Fani, Michel. Dictionnaire de la peinture au Liban. Paris: Éditions Michel de Maule, 2013.

Faubion, James D. Modern Greek Lessons: A Primer in Historical Constructivism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1993.

Getsy, David J. “Ten Queer Theses on Abstraction.” In Queer Abstraction, edited by Jared Ledesma, 65–66. Des Moines, IA: Des Moines Art Center, 2019. Catalogue of an exhibition held at Des Moines Art Center, Des Moines, IA, 1 June–8 September 2019.

Hakim, Victor. “Fadi Barrage à ‘Dar el-Fan’.” La Revue du Liban, 19 February 1972.

Hakim, Victor. “Fadi Barrage à ‘L’Orient’.” La Revue du Liban, 9 March 1968.

Hakim, Victor. “Fadi Barrage à ‘L’Orient’.” La Revue du Liban, 20 February 1971.

Maasri, Zeina. Cosmopolitan Radicalism: The Visual Politics of Beirut’s Global Sixties. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020.

Maltzahn, Nadia von. “1982: Fadi Barrage, Sleeping Boy Drawings.” In Chronicle of the 1980s: Representational Pressures, Departures, and Beginnings in the Arab World, Iran, and Turkey, edited by Anneka Lenssen, Nada Shabout, and Sarah Rogers. Cairo: American University in Cairo Press, forthcoming.

Malusardi, Flavia Elena. “Committed Cultural Politics in Global 1960s Beirut: National Identity Making at Dar el Fan.” Biens Symboliques / Symbolic Goods 15 (2024): 1–31. https://doi.org/10.4000/13kxy.

Parramore Eggerickx, Dorothy. “Barrage at Modulart This Week: A Continuous Embrace with Mortality.” Gallery, March 1975.

Riedel, Brian. “The Movement That Was Not? Gay Men and AIDS in Urban Greece, 1950–1993.” In AIDS, Culture, and Gay Men, edited by Douglas A. Feldman, 231–49. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2010.

Rifaii, Yasmine, and Nadim Choufi, eds. I Will Always Be Looking for You – A Queer Anthology on Arab Art. Beirut: Haven for Artists, 2025.

Salamé Abillama, Nour, and Marie Tomb. L’art au Liban: Artistes modernes et contemporains 1880–1975, vol. 1. Beirut: Wonderful éditions, 2012.

Scheid, Kirsten L. Fantasmic Objects: Art and Sociality from Lebanon, 1920–1950. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2022.

Sultan, Faisal. “Ghiyab Fadi Barraj: al-fanan al-shahid wa al-fanan al-dahiya.” [The departed Fadi Barrage: The artist who was a witness and the artist who was a victim]. As-Safir, 29 January 1988, n.p.

Tarrab, Joseph. “Le fumeur et la fumée: Fadi Barrage à la Galerie ‘Rencontre’.” L’Orient-Le Jour, January 1981.

XIV Salon d’Automne. Beirut: Sursock Museum, 1988. Catalogue of an exhibition held at the Sursock Museum, Beirut, December 1988–January 1989.