How to cite

Abstract

This article discusses how the visualization of Mahmud Ghazan, the sixth Ilkhanid ruler, was employed to construct and propagate his image as the Padishah-i Islam (King of Islam), thus justifying him both as king of Iranshahr (land of Iran) and the legitimate successor of the Prophet Muhammad. In a quest for visual translations of the Ilkhanid concept of Padishah-i Islam—an inseparable combination of the Persian notion of ideal kingship and prophethood—several illustrations from the Diez albums representing Ghazan or events of his reign have been identified, two of which have become subject to detailed iconographic analyses.

Two approaches to the visualization of Ghazan as Padishah-i Islam can be considered here. The first is Ghazan’s birth scene where the visual narrative is covered in various formal and semantic layers; transformed into a symbolic narrative of a holy birth associated with those of the prophets. The second appears in the scene of Ghazan’s enthronement, probably once illustrated as an unknown manuscript’s frontispiece, the images’ composition and components appear as a visual panegyric poem which applies an elaborate visual language that elevates Ghazan to the level of a divine king.

Keywords

Ideal Ruler, Padishah-i Islam, Mahmud Ghazan, Farr-i Izadi, Diez Albums

This article was received on 11 July 2022 and published on 9 October 2023 as part of Manazir Journal Vol. 5 (2023): “The Idea of the Just Ruler in Persianate Art and Material Culture” edited by Negar Habibi.

Introduction

Half a century after Hulagu Khan conquered Baghdad in 1258, Ghazan Khan (r. 1295-1304), the sixth Ilkhanid ruler, proclaimed the Shahadah and converted to Islam. This event occurred during the Mongol emirs’ assembly which was held while Ghazan was fighting against his uncle, Baidu, over the throne in 1295. Though Rashid al-din (1247-1318), the Ilkhanid minister and court historian, stated that Ghazan’s conversion resulted from “God’s guidance,” according to Charles Melville, it was additionally a strategic decision aimed at support from the Iranians and new Muslim emirs such as Nowruz (“Pādshāh-i Islam” 159-160).1 Four months later, Baidu was defeated and murdered by Nowruz, and the Ilkhanid capital, Tabriz, was conquered. Ghazan sat on the throne with a new Islamic name, Mahmud, and the honorific title Padishah-i Islam.2 Following his command, the Mongols immediately converted to Islam, and a new era began; the churches and Buddhist monasteries were destroyed and the Chinggis law (Yasa) was replaced by Islamic law (Bayani 213).

It is worth mentioning that the title Padishah-i Islam (King of Islam) was by no means confined to the Ilkhanid rulers. In several Persian texts from the 12th century onwards, numerous Muslim rulers who reigned over both eastern and western territories were addressed as Padishah-i Islam, especially in book dedications.3 Furthermore, many titles with a similar meaning, such as Sultan-i Islam and Malek al-Islam, could be found in such historical texts. It may seem that addressing Ghazan as Padishah-i Islam was merely a courtly ritual in Islamic lands, but as I discuss below, applying this title to Ghazan was a conscious political act. Beyond simply legitimizing an alien king to rule over Iran, the Ilkhans and their Iranian viziers also pursued the ambitious goal of governing the Islamic world from the heart of the ancient Iranian territory; an ambition that was pursued for centuries, and the fall of the Caliphate prepared the ground for this goal after six hundred years.

Exploring Ghazan’s conversion in the context of the transformations that changed the Islamic world in the second half of the 13th century could provide us with a more complete picture of the above-mentioned goal. The conquest of Baghdad in 1258 and the execution of the Abbasid caliph, al-Mustaʿsim, terminated the symbolic role that the Caliphate had played in the medieval Islamic world for the previous six centuries. The transformation of political and spiritual power was crucial for Iranian elites who accompanied the Mongols in the conquest of Baghdad. As an Islamic city, Baghdad was built in the territories called the heart of Iranshahr, the ideal realm of Persian ideal rulers. In Iranian political thought, Iranshahr was perceived as the center of the world and the realm of the ideal kings. Various geographical locations were attributed to it in sources from the early Islamic centuries. Despite Muslim writers’ disagreement at the time on the precise boundaries of Iranshahr, Iraq and its center, Ctesiphon, the former Sassanid royal capital, was widely considered as the heart of Iranshahr (Daryaee and Rezakhani 8-13; Mottahedeh 155-157).

Consequently, the conquest of Baghdad and the overthrow of the Caliphate became a prerequisite for the Iranian movements of the early Islamic centuries, whose ambition was the revitalization of the Sasanian Empire (224-651). Even though it seems that the Mongol invasion made the ambitious dream of conquering Iranshahr achievable, as Fragner argues, in the context of the 13th century, the revival of an ancient empire was not what the Mongol rulers nor their Iranian vizier envisioned. Their goal was, instead, to reinvent Iran as a “new regional power” following former Islamic models, even that of the extinct Caliphate (73). At this critical juncture, Ghazan was presented as Padishah-i Islam in order to legitimize his rule over Iranshahr and its Muslim residents (Kamola 59).

In order to rule over Iranshahr, a king must have been granted Farr-i Izadi (divine glory). This ancient concept was theorized by Iranian-born thinkers such as Nizam al-Mulk (d. 1092) and al-Ghazali (d. 1111) as the emergence of Turk dynasties in eastern territories caused a decline in caliphal power. In his book Siyar al-Muluk or Siyasatnama, Nizam al-Mulk stated that the legitimacy of a king does not depend on being appointed or approved by the caliph but is obtained only by God’s will. His book begins with a brief description of an appointed king:

In every age and time, God (be He exalted) chooses one member of the human race and, having endowed him with godly and kingly virtues, entrusts him with the interests of the world and the well-being of His servants; He charges that person to close the doors of corruption, confusion, and discord, and He imparts to him such dignity and majesty in the eyes and hearts of men, that under his just rule, they may live their lives in constant security and ever wish for his reign to continue (Nizam al-Mulk 9).

These words clearly indicate the revival of the Persian concept of the ideal king, to whom the Farr-i Izadi is dedicated, as the representative of God on earth (Tabatabai 134, 145). In Nasihat al-Muluk, a book attributed to al-Ghazali, the author lists embodiments of Farr-i Izadi, including inherent characteristics (gawhar-i shahi) and acquired skills (hunarha-i shahana):

The divine effulgence [Farr-i Izadi] is expressed in sixteen things; intelligence, knowledge, sharpness of mind, ability to perceive things, perfect physique, literary taste, horsemanship, application to work, and courage; together with boldness, deliberation, good temper, impartiality towards the weak and the strong, friendliness, magnanimity, maintaining tolerance and moderation, judgment and foresight in business, frequent reading of the reports of the early Muslims, and constant attention to the Biographies of the Kings and inquiry concerning the activities of the Kings of Old […] (al-Ghazali 74).

We see in Ghazan’s conversion account in Tarikh-i Banakati, that the process of elevating Ghazan to the status of the Just Ruler and a ruler who was selected by God is adequately demonstrated. In this text, written during the reign of Ghazan, he is presented as the savior of Islam. The author reported an assembly just before the conversion of Ghazan to Islam. There, Amir Nowruz referred to a prediction made by astrologers and Islamic scholars that a great king would emerge circa 1290 and turned the religion of Islam, which had become “threadbare” (mundaris) by that time, into a “fresh” (taza) religion. Nowruz also pointed out that the signs of the savior king were obvious in Ghazan. If he converted to Islam he would be the one in authority (Ulu'l-amr), and all Muslims would owe him obedience (Banakati 454). A few weeks later, following the defeat of Baidu and his murder in the wars of succession, Nowruz announced Ghazan’s victory in numerous letters written to different parts of the country and declared that “Ghazan is the Padishah-i Islam” (Melville, “Pādshāh-i Islam” 172).

Focusing on illustrated manuscripts, in this article, I deal with the visual representations of Ghazan that aimed to legitimate him as Padishah-i Islam. Art historians who have explored the arts of the book in Ilkhanid Iran have confirmed the use of the book as a tool in Ilkhanid propaganda.4 Sheila Blair, who has conducted in-depth research on Ilkhanid manuscripts, especially on a splendid manuscript of Ferdowsi’s Shahnama (Book of Kings) known as the Great Mongol Shahnama, and Jameʿ al-Tawarikh (Compendium of Chronicles), argues that Ilkhanid patrons applied the history and epic as means to legitimize their domination over Iran. According to Blair, illustrations were not simply a way of beautifying the books or providing a visual narrative of the text. Moreover, each scene is chosen and painted in a way to express a contemporary political situation or to propagate a political message (“Development of the Illustrated Book” 270). The Great Mongol Shahnama is a typical example of interpreting Shahnama scenes as contemporary Mongol history.5 Though this idea was later criticized by Blair and Bloom as well as David Morgan for lack of evidence (Morgan, “Oleg Grabar and Sheila Blair” 364-365; Blair and Bloom, “Epic Images and Contemporary History” 41-52), the importance of the Shahnama in the Ilkhanid Propaganda is confirmed by a body of research done on various aspects of Ilkhanid Art.6

In addition to the Shahnama, paintings from Jameʿ al-Tawarikh, the most important book from the Ilkhanid era, have been the subject of various research. Exploring the paintings from the Arabic manuscript of Jameʿ al-Tawarikh, Ms. Or. 20, now kept in the Edinburgh University Library, Melville argues that Rashid al-Din supervised the selection of the illustrated scenes. He suggests that the abundance of paintings describing the Turk rulers compared with the lack of pictures of ancient kings of Iran was intentional (“Royal Image” 354). Thus, he interpreted the representation of Ghaznavids’ militancy and the dignity of the Seljuk enthroned sovereigns as an allusion to two phases of Mongol history: the conquests and the establishment of the empire (356).

It is important to note that previous research was mainly focused on how the Ilkhanids perceived the history of the ancient kings and pre-Mongol Islamic rulers of Iran. As I will discuss in the following sections, none of the preserved Ilkhanid manuscripts of Jameʿ al-Tawarikh from the 14th century includes the chapters of Ghazan and his successors. The only images from the 14th century that illustrate the Ilkhanid courts are among the fascinating selections of Persian painted pages in the Diez Albums preserved in the collection of the Oriental Department at the Berlin State Library.7

Scholars of Persian art have explored the Diez Albums since the 1950s. However, the paintings became subjects of extensive studies in the 2010s following their digitisation. The results were presented at a Berlin symposium in 2013 and published in The Diez Albums: Contexts and Contents in 2016. Three chapters of the book, written by Charles Melville, Yoka Kadoi, and Claus-Peter Haase, deal with the contents of the images which represent Mongol courts and their court culture. These images are at the center of my study. As the title of this article suggests, I have specifically concentrated my focus on the sections of Ilkhanid history where Ghazan, events of his reign, and measures attributed to him are the main subject, and I have sought for visual evidence that reflects them. I interpreted the visual evidence in the context of the Ilkhanid political situation, their reception of the Shahnama as the history of Iran, and their approach to Islamic historiography.

Gawhar and Hunar in Tarikh-i Mubarak-i Ghazani

One essential source that portrays Mahmud Ghazan as the Padishah-i Islam is Tarikh-i Mubarak-i Ghazani (The Blessed History of Ghazan), an official narrative of the Mongols’ history, compiled by Rashid al-Din as the first part of his Compendium of Chronicles. According to its introduction, the book’s writing began in 1302 following Mahmud Ghazan’s royal command.8 Tarikh-i Mubarak starts with the history of his Mongol ancestors, a detailed biography of Chinggis Khan, including his early life, battles, conquests, and reign, followed by chapters narrating the rule of his sons and grandsons in conquered lands, including Iran. Each chapter consists of three parts (qism): the first is dedicated to family (wives, children, and the family tree), the second part describes the reign of each khan, and the third consists of various anecdotes related to their life and reign.

The story of Ghazan is told in the final chapter. The first part begins with a description of Ghazan’s ancestry, introducing his wives and children, and continues with accounts of his birth and childhood when he was being groomed for kingship with royal knowledge and skills under the supervision of his grandfather Abaqa Khan. The author’s emphasis on his birth is significant considering that in chapters dedicated to other Mongol khans, except in the biography of Chinggis Khan, their birth and early years are not recounted. The second part is dedicated to succession wars, conversion to Islam, and the events of his reign until his death in 1303. The third part consists of forty anecdotes about his personality and the political and economic reforms he made during his reign. Carefully designed, this part aims to fulfill a political idea, to introduce him as a king with divine glory (Padishah-i farahmand). Numerous anecdotes about his characteristics could be considered examples of divine glory; his knowledge of various arts, being infallible and chaste, being eloquent in debate, his adherence to agreements, generosity, courage, and being in service of the prophet’s family (Rashid al-Din, Tarikh-i Mubarak 161-200). The other group of accounts describes a set of measures known as Ghazan’s reforms (Islahat-i Ghazani) where we see an emphasis on the implementation of justice (Morgan 101-103).

In the first half of the 14th century several royal workshops were active under the supervision of Rashid al-Din, in which religious and historical books, especially his own compilations, were copied, illuminated and illustrated. According to the endowment deed of the Rabʿ-i Rashidi, manuscripts of Jameʿ al-Tawarikh were produced in these workshops annually and sent to different parts of the country (Azzouna, “Rashīd Al-dīn” 192, 196-198). However, today, only three mutilated manuscripts remain: a copy in Arabic divided between the University of Edinburgh library (Ms. Or.20) and the Khalili collection (Mss. 727), and two copies in Persian in the Topkapi Palace library (H. 1653 and H.1654) (Blair, A Compendium of Chronicles 27). None of these copies include the story of Ghazan.

In the 18th century, some illustrated folios that once belonged to a missing copy of Tarikh-i Mubarak-i Ghazani were acquired and taken to Berlin by Heinrich Friedrich von Diez, a German diplomat, orientalist and book lover. These are among the other paintings, drawings and calligraphy work now preserved in the Diez Albums. (Diez A, fol. 70-74). Art historians have attributed these paintings to the Rabʿ-i Rashidi workshops around 1320 through the identification of their stylistic features (Kadoi 246-247; Blair, A Compendium of Chronicles 93-95). Identifying the subject of each image and reconstructing the mutilated manuscript is difficult because the images were cut from their original setting and pasted into an album folio according to their size and color palette. However, comparing the Diez illustrations with those of a 14th-century manuscript of Jameʿ al-Tawarikh in the French National Library (Persan 1113),9 four images from Diez Albums undoubtedly illustrate events from the Ghazan chapter. The first is Ghazan’s birth (Diez A, fol. 70, p. 8, no. 2). The second is the painting that represents men reciting the Quran in luxurious tents (Diez A fol. 70, p. 8, no. 1). The third is the Ghazan mausoleum as described in the thirteenth anecdote of the third part of Ghazan’s story (Diez A, fol. 70, p. 13), and the last is a young woman’s encounter with Ghazan from the thirty-eighth anecdote (Diez A, fol. 70, p.18, no. 2).10 Aside from the birth scene which will be explored later, the other scenes are related to Ghazan’s royal skills (hunar). The Quran reciting scene is a visual narrative of an event described in detail in the book and represents his religiosity. The double-page painting of Ghazan’s mausoleum and related buildings is a manifestation of abadani, which means development and construction, and it is a prerequisite to be a just ruler. Moreover, by building a dome over his grave, Ghazan dissociates himself from his ancestral burial rituals. Again, his being impressed by the mausoleums of Imams and Sufis is a sign of his religiosity (Azzouna, Aux Origines 209). The last image depicts Ghazan’s command to provide housing for state emissaries and prohibit officers from staying in people’s houses11 which is also related to his role as an astute and just ruler (Rashid al-Din, Tarikh-i Mubarak 360-356).

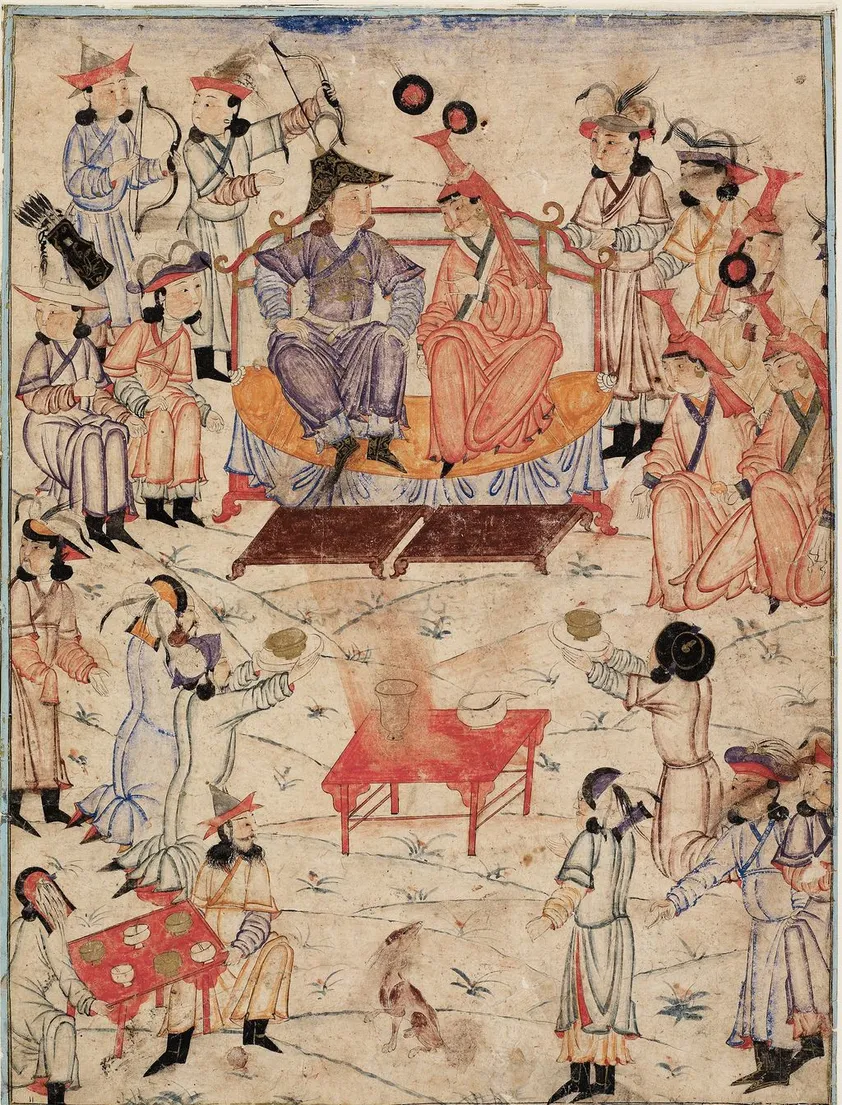

The royal lineage is one of the main themes of the Tarikh-i Mubarak-i Ghazani. In addition to the scenes mentioned earlier, there are four paintings of the Mongol court, one a single page and three double pages, in the Diez Albums. In each painting, a Mongol khan and his consort are enthroned flanked by several princes, princesses, courtiers and attendants (fig. 1).

It is assumed that enthroned khans were identified according to the inscriptions once written in a box on top of the pages (Kadoi 251). The removal of these inscriptions has prevented us from recognizing the enthroned figures. However, Melville believes that none of these paintings illustrate Ghazan’s court due to the absence of men in Persian clothing (“Illustration of Turko-Mongol” 237).

Therefore, whether the enthroned sovereign is identified or not, the court scenes demonstrate the Ilkhanids’ attitude toward their history. Rashid al-Din bolstered their enthusiasm for their ancestral history and the Persian notion of the ideal king to legitimize Mongol rule over Iran. It must be taken into account that according to Persian political ideas, to be granted Farr-i Izadi and rule over Iranshahr, one must be of royal descent (Shahbazi 128). That is why the Iranian kings from local dynasties in the early Islamic centuries traced their lineage back to Sasanian kings. Even the Ghaznavids claimed to be descended from Yazdegerd III, the last Sasanian king (Daryaee and Rezakhani 9). However, Rashid al-Din dealt with Ghazan’s royal lineage differently. The Mongols regard Chinggis Khan as a prophet, a selected man who brought the holy book (Yasa) and a king sent by the heavens to take command of the Turks and the Mongols (Bayani 16-18). As Rashid al-Din states in the introduction, what motivated him to write Tarikh-i Mubarak was Ghazan’s enthusiasm for the history of his ancestors and a need to organize the oral narratives and scattered documents of the history of the Mongols (8). So, being from the Chinggisid lineage became a legitimizing factor and even Timurids and Mughals built their legitimacy upon their Mongol ancestry.

The importance of the royal lineage is exemplified in the narrative of the conquest of the Levant by Ghazan from Tarikh-i Mubarak. There, Ghazan addressed the surrendered residents of Damascus and asked them, who am I? The crowd said, you are the King Ghazan, son of Arghun Khan, son of Abaqa Khan, son of Hulagu Khan, son of Tolui Khan, son of Chinggis Khan (128). Afterward, Ghazan asked them about the descendancy of al-Malik al-Nasir ibn Qalawun II, the ninth Bahri Mameluke sultan of Egypt and the Levant. He asked who his father was; they answered he was Alfi. He asked who Alfi’s father was. Then all of them remained silent. So, everybody knew that the reign of [the Mamelukes] was accidental, and not by merit (Rashid al-Din, Tarikh-i Mubarak 128)12. Given this, the religious and political aspects of Ilkhanid rule were rooted in the sanctity of the Prophet Muhammad and the spiritual aspects of Chinggis Khan. Thus, the reign of Ghazan was a continuation of the reign of the Prophet and Chinggis Khan (Brack 2, 6-7).

From this point of view the Mongol court scenes, which insist on the glory of Ghazan’s Mongol descent, also reinforce the book’s central idea of producing the image of Ghazan as a sovereign with royal glory.

The Birth of the Appointed King

It is without a doubt that the birth scene is the most important of the paintings attributed to Ghazan’s story (fig. 2). As mentioned above, the first part of Ghazan’s story and the depiction of his birth are almost unique in this book. At first sight, the painter represents a royal birth using a plain visual language with stylistic features belonging to the Ilkhanid workshops of Rabʿ-i Rashidi. The figures are painted on light brownish-yellow backgrounds in relatively elongated rectangular frames and the interior space is depicted with minimal accessories. A leaning woman wearing a red robe and no headdress is painted on the left resting her head and shoulders on a golden pillow while placing her arm in a supportive gesture next to an infant wrapped in a red cloth. Although no facial detail is recognizable due to the distortion of the mother’s and child’s faces, it seems that the mother looks towards the right, where three men are sitting. Three women are seated in the middle of the scene in front of the mother. Besides sitting on chairs, their royal status is evident from their red robes, long headdresses called boqtaq, unique to Mongol khatuns (high-ranked Mongol women), and golden earrings. In this scene, there are also three maids: one is standing behind the mother wearing a hat adorned with feathers, the second, in similar clothes and hat, sits on the floor with a bended knee and the third stands in front of the mother and holds a thurible in front of her. On the right, two men sit in the front and one in the back. They wear long robes with wide sleeves and white turbans. The men in the front hold round objects, probably astrolabes, and two other objects similar to hourglasses are in front of them on the floor.

In Tarikh-i Mubarak, Rashid al-Din has referred to “skilled astronomers” being present at the moment of Ghazan’s birth. They observed the positions of the stars and predicted an extremely blissful fortune for the newborn and were in agreement that “he would be a great king with extreme magnificence and majesty” (3). By comparing the abovementioned painting with one of the Jameʿ al-Tawarikh folios located in Paris which depicts a similar scene within the section on Ghazan’s birth, there is no doubt about the subject of the Diez painting (fig. 3).13

Furthermore, the scene is similar to Muhammad’s birth scene found in a Jameʿ al-Tawarikh folio housed in Edinburgh, illustrated around 1308, also in Rabʿ-i Rashidi (fig. 4). Finding no previous painting of the Prophet’s birth, Blair believes that this painting is influenced by nativity scene paintings that were provided as models for painters working at Tabriz’s workshops. According to Blair, in the Jameʿ al-Tawarikh painting, Joseph was replaced by the Prophet’s grandfather, ʿAbd al-Muttalib, who sat on the right. On the other side, three standing women were painted instead of the Magi who traveled to Bethlehem to visit the infant Christ (A Compendium of Chronicles 69). In Gazan’s birth scene, there are also three men, the astronomers. While there is no other man, this unusual presence could be related to the Magi in the number and their functions in both narratives that link them to the predictions of the infant’s future.

A Nativity scene in a Syriac manuscript from the Vatican Library (Vat. sir. 559, fol 16r) may be similar to the models that Ilkhanid painters had referred. The manuscript was produced for the Monastery of Mar Matti near Mossul in 1219, almost 100 years before the birth scene in the Diez Albums has been painted. Several scenes related to the infant Christ were painted in a single frame here.14 In the upper part, where the Magi visit the mother and the child, the half-risen gesture of Mary, her gaze at the three men standing on the left, and the newborn lying beside her on a golden bed are similar to Ghazan’s birth scene. Textual evidence demonstrates that it was not merely a visual adaptation and that painting this particular scene according to the nativity scene was done intentionally. In the paragraphs following Rashid al-Din’s account of Ghazan’s birth in Tarikh-i Mubarak-i Ghazani, he compared Ghazan with a prophet. First, he pointed to selecting a wet nurse for newborn Ghazan and then wrote about his ability to talk while still in the cradle. Both of these can be considered allusions to the prophets Muhammad and Christ. He also compared Ghazan’s appearance and deeds with the prophets: he is handsome as Joseph, courteous as Moses, bright as Christ and well-spoken as Muhammad (6). These implications are not restricted to the first part of Ghazan’s story. In the first anecdote of the third part, he compared Ghazan with Abraham, who converted to the worship of God in the light of divine guidance, broke the idols, and destroyed the temples (169).

The Icon

Here I turn to a detailed examination of a single image from the Diez Albums that has a peculiar iconography (fig. 5). The separated folio, now pasted in Diez A fol. 71, is seriously damaged with most of the faces, hands, and draperies having lost detail and color. In the center, a man in a golden robe wearing a white turban is enthroned on a blue throne flanked by two seated men in luxurious robes and feather hats. Three angels with bare chests and golden wings hover over the throne. The angel in the middle is directly above the head of the enthroned figure and slightly touches the highest part of the throne. The most noteworthy elements are the angel’s full-face representation, and the peacock feather ornamentation on the lower part of her body. While it is unclear if they hold any objects in their hands due to the severe damage of the image, we see the other two angels point their fingers toward the throne from either side.

In one of the earliest studies on the Diez Albums, Mehmet Şevket İpşiroğlu assumed it reasonable to put this royal scene into the category of Seljuk-Mongol style by identifying some stylistic features in the faces and the throne (İpşiroğlu 12). This category indicates a transitional phase in Persian painting in the medieval period. During this phase, which began in the second half of the 13th century in Baghdad and ended with the establishment of the Rashidi workshop in Tabriz, the Seljuk style gradually mixed with eastern motives. However, the feather hats and generous use of gold, especially in backgrounds, clothes and accessories, are indicative of the small Shahnamas attributed to Baghdad workshops around 1300 (Simpson, Illustration of an Epic 272). Moreover, some details in painting portraits and draperies also confirm its attribution to the early 14th century (Haase 280).

Illustrating this trichotomous composition in which a ruler is enthroned in the center among his courtiers and attendants with angles, sometimes holding a ribbon, flying over his throne, in the opening pages of the manuscripts was prevalent at least from the 12th century in Mesopotamian workshops (Simpson, “In the Beginning” 213; Blair, “Une brève histoire” 61). Similar frontispieces from Ilkhanid manuscripts are known, including the one at the beginning of an illustrated manuscript of Tarikhnama, now in the Freer Gallery (fig. 6). Both attributed to the early 14th century, the Tarikhnama frontispiece and the Diez painting have similar features that extend beyond just their subject matter, such as their composition and the way the enthroned figure is represented.15

Compared with other illustrated frontispieces belonging to the same period, these similarities confirm that the Diez painting was once illustrated as a frontispiece of an unknown manuscript. Now a significant question regarding a manuscript frontispiece must be discussed: who is the enthroned figure?

This question related to the frontispieces’ function as visual dedications praising the patron often has no straightforward answer especially in the cases like Diez’s frontispiece where the painting is detached from its original setting (Simpson, “In the Beginning” 242). In the case studied here, as I argue below, the figure with a turban, holding a bow and enthroned among a group of men with Mongol feathered hats is most likely Ghazan Khan, Padishah-i Islam. I propose primarily an interpretation of this image since our lack of knowledge about the original manuscript makes it challenging to identify the enthroned figure. However, as I will argue further, some iconographic features in this folio will show that a symbolic analysis is not useless.

According to the frontispiece tradition, the figure can be the book’s author or his patron. While exploring frontispieces from the 12th and 13th centuries, Blair observes a visual convention according to which the author’s portraits were painted in three-quarter view, possibly reciting their book. However, rulers or patrons were portrayed full-faced and in royal settings (Blair, “Une brève histoire” 57). Moreover, in the Diez frontispiece, the royal symbols are so evident that it is hard to identify the seated figure as the author. As mentioned, wearing a turban instead of the usual crown may be the key to identify the enthroned figure. Does he represent the Prophet Muhammad, an Arab ruler or maybe a caliph? The caliph cannot be represented while enthroned among Mongol emirs and attendants, but whether it represents the Prophet or not deserves more investigation.

The enthroned Prophet is among the illustrated scenes in some Ilkhanid manuscripts such as the Freer small Shahname (fig. 7) and the Marzbannama.16 Several considerations regarding these images must be taken into account. First, both manuscripts are dated around 1300.17 Second, both images are illustrated in the book’s preface, followed by an image of the patron in a royal setting. Third, the flying angels were only painted over the Prophet’s throne. Fourth, in two ways, the enthroned Prophet, especially in the Freer Shahnama, differs from the enthroned kings in the same manuscript as he does not wear a crown but a turban covered with a long shawl and is represented in a three-quarter view. The enthroned kings are represented in frontal view with open chests. They are seated crossed legs with a boot always visible though wearing a long robe (fig. 8). This gesture is familiar in several royal images in Ilkhanid paintings as well as in the Diez frontispiece. In contrast, the Prophet slightly turns to the right as if he is talking to his fellows, and his long robe covers his feet completely. The three-quarter view presentation is in line with Blair’s distinction between portraying authors and their patrons in frontispieces. Moreover, the painter deliberately avoided royal iconographic conventions in representing the enthroned Prophet. A complicated setting accompanied by royal attributes, two lions, and the golden bow distinguishes this painting from an iconography of the enthroned Prophet.

In the Freer Shahnama and Marzbannama, the Prophet is enthroned among the Rashidun caliphs as well as his companions. In the Diez frontispiece, several attendants fill the scene and two men (probably emirs) are seated by the throne while two other men are holding parasols behind the throne. The hajibs and royal guards also stand in the lower part.

Returning to the main question, how could the turban be interpreted as an attribute of Ghazan khan? To cast light on this issue, we must have a look at the 1297 events. According to Tarikh-i Mubarak and Tarikh-i Wassaf, Ghazan was crowned with a turban in Muharrim of 697 A.H. (1297). While Rashid al-din briefly reported the event (Tarikh-i Mubarak 117), Wassaf provided a more detailed description. In his narration, he pointed to Ghazan’s turban with the word Tijan (a plural form of Taj that means crown) and used the verb motavaj shodan, which means to crown.

Moreover, using highly elaborate language, he pointed to a change in the Mongol emirs’ clothing, describing that they dressed as believers without mentioning the turban as a part of their new uniform. Even though by believers’ clothing, he meant that Mongol emirs were dressed in Iranian robes and turbans, the specific use of the verb “to crown,” indicates that the writer perceived the turban as a royal crown for Ghazan.18

According to Tarikh-i Wassaf, wearing the turban should be considered a symbolic and strategic act at a critical juncture as Ghazan was planning his second attack on the Levant. Additionally, Ghazan’s legitimacy at that time had become vulnerable due to the execution of Amir Nowruz. Being afraid of losing his Muslim supporters, Ghazan exaggerated the importance of Islamic laws, according to Wassaf. The other significant point in the Wassaf narrative is Ghazan’s decree that no one can force Tajiks (here meaning non-Turk or non-Mongol) to wear a Mongol hat.

This command was probably issued to gain the support of the Iranians as the leading group of Nowruz’ followers (Bayani 216). At the same time, it shows that the Mongol community did not abandon the Mongolian hat.

Turning to the three flying angels over the throne, two unusual things become readily apparent. Illustrating two hovering angles holding a ribbon over the enthroned figure is the standard way of painting them in the enthronement scenes. This being said, in the Diez frontispiece, there are three angels over the throne, and none of them holds a ribbon. There are two possible explanations for why the painter has avoided a typical pattern: he used other models or intended to convey a different message by altering the prevalent pattern.

In the ancient representations of flying angels on Sassanid reliefs, they hold small ribbons as a sign of victory (Soudavar, Aura of Kings 13). In the 12th and 13th centuries, the short ribbons were replaced by a much longer ribbon placed in a curved form over the ruler’s head. Its shape bears in mind the victory arch with two angels on both sides, according to Hillenbrand (210). Furthermore, in the ancient Near East, the arch and ribbon are associated with casting shadows by a parasol over dignitaries’ heads (210). This practice continued during the Islamic period and was reflected in literary texts as a sign of divine endorsement and protection.19

How do we then consider the flying angels with no ribbon in their hands? In Ajaʿeb al-Makhluqat (Wonders of Creation), written in the 11th century, the author describes Solomon’s court in the ancient city of Istakhr. According to Tusi, two archangels stood over Solomon’s throne, Gabriel on the right and Israfil on the left (178). This provides us a valuable clue.

As mentioned, something like a peacock tail adorns the lower body of the central angle in the Diez frontispiece which is a clear symbol of paradise and the sun, both divine symbols in Islamic culture.20 Moreover, Gabriel is described as the peacock of the angels in Persian poetry (Latifkar 27n42). In a hadith quoted from Muhammad, “Gabriel has six hundred wings [adorned] with pearls, and he spread them out like peacocks’ feathers” (Al Suyuti 121). Thus, does this textual evidence suggest that the central angel represents Gabriel? In other words, is it convincing to identify the flying figure supporting the throne of an earthly sovereign as the angel of revelation?

Such an image is not unprecedented in Persian poetry. For instance, in the 12th century, Hasan Gaznavi praised Bahram shah of Ghazna by depicting Gabriel over his throne (81). In the introductory verse, the poet describes his patron’s court as a place worthy of Gabriel’s presence which means the divine approval of Bahram Shah. He also points out that God appoints the king to rule the world from the east to the west (Afaq). Being appointed by God to rule correlates the ideal kingship with prophethood. This idea was noticed in the early Islamic centuries among Muslim historians and thinkers such as Shahab al-Din Suhrawardi (Tabatabai 160). In Alvah-i ʿImadi, he wrote that pre-Islamic kings such as Fereydun and Kay Khosraw were granted Farr-i Izadi by God talking to them through the Holy Spirit (Suhrawardi 186-187).21

In Ghazan’s conversion ceremony, Amir Nowruz addressed Ghazan Khan as Ulu'l-amr. This term is driven from the Quran (An-Nisa 4: 59), where the believers were addressed to obey God, the Prophet, and “those having authority among you,” referring to “the appointees of the Prophet representing his authority in his absence” (Blankinship 567). Thus, by addressing Ghazan as Ulu'l-amr, Nowruz introduces him as the Prophet’s successor, which coincides with the concept of the ideal ruler in the Islamic period (Tabatabai 163). That is why the king is higher in position than the caliph since the king is God’s immediate appointee, and this divine approval is the mentioned Farr-i Izadi (164). A combination of textual and visual manifestations of divine approval can be found in the Tarikhnama manuscript’s frontispiece. In an elaborated rectangular frame located on the top, over the head of the enthroned ruler, part of a verse from the Quran (Saad 38: 26) has been written (fig. 9). This verse is significant in Islamic political thought because it is the only verse in the Quran in which the word caliph is used in a political sense (Kadi 277-278). Less than a century before the Mongol invasion, Najm al-Din Razi (d. 1256), a Persian Sufi, had interpreted this verse in his book Mersad al-ʿebad to support his idea of the unity between religion and kingship (232-244).

According to him, referring to David as God’s caliph on earth shows that “kingship is khilafa of God and that justice is of its essence” and “kingship over men may be joined to the rank of prophethood” (Crone 253).22

Thus, it is evident how the Iranian courtiers apply a prevalent idea to legitimize Ghazan’s rule over Iran. Returning to the Diez frontispiece, though identifying two angels on the right and left sides is still debatable, I believe this evidence can justify the presence of an angel carrying the divine message over the king’s throne.

The enthroned ruler on the Diez frontispiece is accompanied by two essential attributes of the ideal king: the bow and arrow, and the lion throne. A king enthroned on the lion throne is among the popular images in Islamic lands. Though it is impossible to fully determine this image’s origin in Islamic narratives, the lion is related to two kings, Solomon and Bahram IV, the latter also known as Bahram Gur. In the story of Solomon, lions appear as the guardians of his throne and prevent the unjust king from accessing it (Neysaburi 303; Soucek 114). The lion also protects the royal throne and crown in the narratives of Bahram Gur found in Ferdowsi’s Shahnama and Nizami’s Haft Peykar (Seven Portraits). To be enthroned as the King of Iran, Bahram Gur had to prove his legitimacy by getting the crown from the throne guarded by two lions. According to Ferdowsi and Nizami, he kills the lions with his famous mace. Still, in Persian literature, he is generally praised for his skill in archery, especially in the story of Bahram and Azade where he stucks a dear’s ear with its leg. The visual representations of this story were popular in medieval centuries. In an account of Ghazan hunting in 701 A.H. (1301 A.D.) from Tarikh-i Mubarak, Rashid al-Din compares Ghazan’s skills in archery with that of Bahram Gur. He wrote that Ghazan shot a deer with one arrow and made nine wounds on its body. Then he claimed that after Ghazan’s magnificent shot, the image of Bahram Gur was no longer being painted on walls or in books (Tarikh-i Mubarak 133).

Another piece of evidence is found in Ghazan-Nama, a verse chronicle of the Ilkhanid dynasty, composed by Nouri Azhdari for Sultan Sheikh Uways, the Jalayirid ruler of Iraq (Nuri Azhdari 6). Similar to the verse chronicles of the Ilkhanid era, Azhdari imitates the Shahnama in form and meaning. Though the narratives of Ghazan’s reign are at the book’s core, a mythical image of him is presented as the “philosopher king and just ruler” based on narratives of Iranian kingship from the Shahnama and the Iskandarnama by Nizami (Melville, “History and Myth” 142). Azhdari’s portrayal of Ghazan is comparable to the Iranian king-heroes with marvelous deeds, including fighting with beasts, killing a dragon, and obtaining Alexander’s treasure. Portraying him as a dragon slayer and being led to royal treasures is reminiscent of Bahram Gur’s narrative in Shahnama. To conclude, reading this image in the light of the analogy between Ghazan and Bahram Gur in Ilkhanid historical texts, the archer king seated on the lion throne in the Diez frontispiece can be interpreted as Ghazan. He is portrayed with symbols attributed to Bahram Gur as a symbol of the ideal king. Additionally, the turban and the revelation angel indicate his legitimacy as a Muslim ruler. Thus, the memory of Persian kingship is combined with Islamic ideals in Ghazan’s image.

Conclusion

To create and present the image of Ghazan khan as Padishah-i Islam, in addition to Rashid al-din’s extensive programs of historiography, inherited visual traditions and the symbolic structure and language were used in Ilkhanid royal workshops. Ghazan’s birth scene, while at first glance a simple visual narrative of a blessed birth, also proposes a selection of intertextual references that transformed it from a straightforward visual narrative to part of the symbolic framework in which the imagery of Ghazan as an ideal king was created. In other words, the juxtaposition of the image with its history and the historical text created new layers of meaning. The painting functions similarly to the method that historians such as Rashid al-din used to narrate and orient the events of Ghazan’s reign. Hence the visual and textual narratives integrate as a whole in order to form the concept of a savior king or ideal ruler.

In addition to visual narratives, the creation of symbolic images of the ideal king is another way to transmit a political message. As in the case of the Diez frontispiece, no specific narrative has been visualized. Instead, all of the image components, from the composition to symbolic motives, express the idea of Padishah-i Islam. The ancient form of a royal figure enthroned on a lion throne is combined with other motives to create new form and meaning in the sociopolitical context of the 14th century. Moreover, compared with literature that goes hand in hand with art in Persian culture, the Diez frontispiece is similar to a panegyric poem praising Ghazan Kan. The visual language of the painting and the imaginative expression of the concept of the ideal ruler are identical to how a poet chooses his words and applies stylistic devices. Therefore, all symbolic and aesthetical components of the image or poem follow the particular aim of making a symbolic image of Ghazan.

These two paintings which represent a king with prophetic features, illustrate the concept of the ideal ruler in which kingship and prophethood are inseparable. With all of its references, the visual representation of Ghazan’s birth follows the textual and visual narratives in elevating a royal birth to a divine one. However, the symbolic language used in the Diez Album painting, as is seen in panegyric poetry, praises Ghazan as an ideal king that has been granted divine approval.

Bibliography

Al-Ghazali, Muhammad ibn Ahmad. Ghazali‘s Book of Counsel for Kings. Translated by F. R. C. Bagley. Oxford UP, 1964.

Al-Suyuti, Jalal al-Din. Angels in Islam: Jalal al-Din al-Suyuti's al-Haba'ik fi akhbar al-mala'ik. Translated by Stephen Burge. Routledge, 2015.

Allsen, Thomas T. Culture and Conquest in Mongol Eurasia. Cambridge UP, 2004.

Azzouna, Nourane Ben. Aux Origines du classicisme: calligraphes et bibliophiles au temps des dynasties mongoles. Brill, 2018.

---. “Rashīd Al-dīn Faḍl Allāh al-Hamadhānī’s Manuscript Production Project in Tabriz Reconsidered.” Politics, Patronage and the Transmission of Knowledge in 13th - 15th Century Tabriz, edited by Judith Pfeiffer et al., Brill, 2013, pp. 187-200.

Banakati, Davud b. Muhammad. Tarikh-i Banakati, edited by Jaʿfar Sheʿar, Anjoman Asar-i Melli, 1348/1969.

Bayani, Shirin. Mughulan wa Hukumat-i Ilkhani dar Iran. SAMT, 1389/2010.

Blair, Sheila S. and Jonathan Bloom. “Epic Images and Contemporary History: The Legacy of the Great Mongol Shah-Nama.” Islamic Art, vol. 5, 2001, pp. 41-52.

Blair, Sheila. A Compendium of Chronicles: Rashid-al-Din Illustrated History of the World. Nour Foundation, 1995.

---. “The Development of the Illustrated Book in Iran.” Muqarnas, vol. 10, 1993, pp. 266-74.

---. “The Ilkhanid Palace.” Ars orientalis, vol. 23, 1993, pp. 239-248.

---. “Une brève histoire des portraits d’auteurs dans les manuscrits islamiques.” De la figuration humaine au portrait dans l’art islamique, edited by Houari Touati, Brill, 2015, pp. 31-62.

Blankinship, K. Y. “Obedience.” Encyclopedia of the Qur’an, edited by Jane D. McAuliffe et al., vol. 3, Brill, 2001, pp. 566-568.

Brack, Jonathan Z. Mediating Sacred Kingship: Conversion and Sovereignty in Mongol Iran. PhD thesis, University of Michigan, 2016.

Crone, Patricia. Medieval Islamic Political Thought. Edinburgh UP, 2005.

Daneshvari, Abbas. Medieval Tomb Towers of Iran. Mazda publishers, 1986.

Daryaee, Touraj and Khodadad Rezakhani. From Oxus to Euphrates: The World of Late Antique Iran. Jordan Center for Persian Studies, 2016.

Diez-Albums, Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, Preußischer Kulturbesitz, no. Diez A fol. 70, https://digital.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/werkansicht/?PPN=PPN73601313X. Accessed 12 Sep. 2023.

Diez-Albums, Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, Preußischer Kulturbesitz, no. Diez A fol. 71, https://digital.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/werkansicht/?PPN=PPN635104741. Accessed 12 Sep. 2023.

Fakhr-i Mudabbir. Adab al-harb wa-l-Shajaʿa, edited by A. Sohayli Ḵhansari, Iqbal, 1346/1967.

Fitzherbert, Teresa. “Balʿami’s Tabari”: An illustrated manuscript of Balʿami’s Tarjama-yi Tarikh-i Tabari in the Freer Gallery of Art, Washington (F59. 16, 47.19 and 30.21). PhD thesis, University of Edinburgh, 2001.

Fragner, Bert G. “Ilkhanid Rule and Its Contributions to Iranian Political Culture.” Beyond the Legacy of Genghis Khan, edited by Linda Komaroff, Brill, 2006, pp. 68-80.

Gospel Lectionary with illuminations, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, no. Vat.sir.559, https://digi.vatlib.it/view/MSS_Vat.sir.559/0035. Accessed 21 Dec. 2022.

Ghaznavi, Seyed Hasan. Divan, edited by. S.M. Modarres Razavi, Asatir, 1362/1983.

Grabar, Oleg and Sheila Blair. Epic Images and Contemporary History: The Illustrations of the Great Mongol Shahnama. University of Chicago Press, 1980.

Gruber, Christiane. The Praiseworthy One: The Prophet Muhammad in Islamic Texts and Images. Indiana UP, 2018.

Haase, Claus-Peter. “Royal Insignia in the Periods from the Ilkhanids to the Timurids in the Diez Albums.” The Diez Albums: Contexts and Contents, edited by Julia Gonnella et al., Brill, 2017, pp. 276-91.

Hillenbrand, Robert. “The Frontispiece Problem in the early 13th-Century Kitab al-Aghani.” Central Periphery? Art, Culture and History of the Medieval Jazira, edited by Martina Müller-Wiener and Lorenz Korn, Dr. Ludwig Reichert, 2017, pp. 199-228.

Ibn Munawwar. Asrar al-Tawhid Fi Maqamat al-Saykh Abi Saʿid, edited by Muhammad-Reza Shafiei Kadkani. Agah, 1386/2007.

İpşiroğlu, Mazhar Şevket. Saray-Alben. Franz Steiner, 1964.

Kadi, Wadad. “Caliph.” Encyclopaedia of the Qurʼān, edited by Jane D McAuliffe et al., vol. 1, Brill, 2001, pp. 276-278.

Kadoi, Yuka. “The Mongols Enthroned.” The Diez Albums: Contexts and Contents, edited by Julia Gonnella et al., Brill, 2017, pp. 243-275.

Kamola, Stefan. “Beyond History: Rashid al-Din and Iranian kingship.” Iran After the Mongols, edited by Sussan Babaie, I.B. Tauris, 2019, pp. 55-75.

Latifkar, Azadeh. “The Reinvention of Padishah-i Islam in the Visual Representations of Ghazan Khan (Persian Version).” Manazir Journal, vol. 5, 2023, https://doi.org/10.36950/manazir.2023.5.2

Nizam-al-Mulk. The Book of Government or Rules for Kings. Translated by Hubert Darke, Routledge, 2002.

Neyshaburi, Ebrahim ibn Mansour. Qisas al-Anbia, edited by Habib Yaghmai, Intisharat-i Ilmi va Farhangi, 1382/2003.

Nouri Azhdari. Ghazan-name-ye Manẓum, edited by M. Mudabberi, Bunyad-i Muqufat-i Afshar, 1381/2002.

Madelung, Wilferd. “The Minor Dynasties of Northern Iran”. Cambridge History of Iran, edited by R.N Frye, vol. 4, Cambridge UP, 2007, pp. 198-250.

Melville, Charles. “History and Myth: The Persianisation of Ghazan Khan.” Irano-Turkic Cultural Contacts in the 11th-17th Centuries, edited by Eva M. Jeremias, Piliscsaba, 2003, pp. 133-60.

---. “The Illustration of the Turko-Mongol Era in the Berlin Diez Albums.” The Diez Albums: Contexts and Contents, edited by Julia Gonnella et al., Brill, 2017, pp. 219-242.

---. “Pādshāh-i Islām: The Conversion of Sultan Maḥmūd Ghāzān Khān”. Pembroke Papers I: Persian and Islamic Studies in Honour of P. W. Avery, edited by Charles Melville, University of Cambridge, Centre of Middle Eastern Studies, 1990, pp.159-177.

---. Persian Historiography. I.B. Tauris, 2012.

---. “The Royal Image in Mongol Iran.” Every Inch a King, edited by Lynette Mitchell and Charles Melville, Brill, 2013, pp. 343-370.

Morgan, David O. The Mongols. Blackwell, 2001.

---. “Oleg Grabar and Sheila Blair: Epic images and contemporary history”. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, vol. 45, no. 2, 1982, pp. 364-365.

Mottahedeh, Roy Parviz. “The Idea of Iran in the Buyid Dominions.” Early Islamic Iran, edited by Edmund Herzing and Sarah Steward, I.B. Tauris, 2012, pp. 153-160.

The Qur'an. Translated by Arthur John Arberry, Ansariyan, 2003.

Rashid-al-Din, Fazl-Allah Ṭabib. Tarikh-i Mubarak-i Ghazani, edited by Karl Jan, Porsish, 1388/2009.

---. Jameʿ-al-Tawarikh, edited by M. Rowshan and M. Musavi. Alborz, 1373/1994.

Ravandi. Raḥat-al-ṣodur, edited by M. Iqbal, Brill, 1921.

Razi, Najm al-Din. Merṣād al-ʿebād men al-mabdāʼ ela al-maʿād, edited by Hossein al-Hosseini. Matʿabey-i Majlis, 1312/1933.

Rice, Yael. “Mughal Interventions in the Rampur ‘Jamiʿ Al-Tavarīkh’.” Ars Orientalis, vol. 42, 2012, pp. 150-64.

Richard, Francis. “Un des peintres du manuscrit ‘Supplément Persan 1113’ de l’Histoire des Mongols de Rašîd al-Dîn identifié.” L’Iran face à la domination mongole, edited by Denise Aigle, Institut français de recherche en Iran, 1997, pp. 307-320.

Shahbazi, Alireza S. “An Achaemenid Symbol. II. Farnah (God Given) Fortune Symbolised.“ Archäologische Mitteilungen aus Iran—Neue Folge, vol.13, 1980, pp. 119-147.

Simpson, Marianna Shreve. The Illustration of an Epic: The Earliest Shahnama Manuscripts. Garland, 1979.

---. “In the Beginning: Frontispieces and Front Matter in Ilkhanid and Injuid Manuscripts.” Beyond the Legacy of Genghis Khan, edited by Linda Komaroff, Brill, 2006, pp. 213-247

Smine, Rima E. “The Miniatures of a Christian Arabic Barlaam and Joasaph, Balamand 147.” Actes Du 4e Congrès International d’études Arabes Chrétiennes. Cambridge, Septembre 1992, 2010.

Soucek, Priscilla P. “Solomon’s throne/Solomon’s bath: Model or metaphor?” Ars Orientalis, vol. 23, 1993, pp. 109-34.

Soudavar, Abolala. The Aura Of Kings: Legitimacy And Divine Sanction In Iranian Kingship. Mazda Publishers, 2003.

---. “The Saga of Abu-Saʿid Bahador Khan. The Abu-Saʿidname.” The Court of the Il-Khans, 1290-1340, edited by Julian Raby and Teresa Fitzherbert, Oxford UP, 1996, pp. 95-128.

Suhrawardi, Shehab al-Din. Majmoue-ye Mosannafat-i Sheikh-i Eshraq, edited by S. Hossein Nasr, vol. 3, Pajoohishgah-i Olum Insani va Motaleʿat-i Farhangi, 1373/1994.

Tabatabai, Javad. Khawje Nezam-al-Mulk Tusi: Goftar dar Tadavom-I Farhangi Iran, Minuy-i Khirad, 1392/2013.

Tusi, Mahmud ibn Mhmud ibn Ahmad. ʿAja’ib al-Makhluqat va Ghara’ib al-Mawjudat, edited by Manoucher Sutudeh. Intisharat-i Ilmi va Farhangi, 1382/2003.

Wassaf-e Hazrat. Tarikh-i Wassaf or Tajziyat-al-amsar va Tazjiyat-al-aʿsar. 1670. Bibliothèque Universitaire des Langues et Civilisations, no. Ms. Pers.116, via Internet Archive, https://archive.org/details/MS.PERS.116/mode/2up. Accessed 3 May 2022.

Zahiri Samarqandi. Aghraz al- Siasia fi Aʿraz al-Riyasia, edited by Jaʿfar Sheʿar, Danishgah-i Tehran, 1349/1970.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Dr. Amir Maziar since many of the ideas discussed in this article were refined during conversations I had with him while I was writing my doctoral thesis at Tehran Art University. I also appreciate Dr. Negar Habibi’s encouragement and kind support while writing this article. I am also grateful for the referee’s comments, which greatly helped me make the article revisions. The responsibility for the shortcomings lies with me.