How to cite

Abstract

The Bibi Khanum Congregational Mosque is the largest Timurid monument in Samarqand. Commissioned by Timur himself after his military campaign in India in 1399, the architecture of the mosque can be interpreted as a visual representation of Timur’s ambitions to surpass the architectural achievements of the preceding Islamic dynasties. Striving for political legitimacy beyond the legacy of Chinggis Khan, Timur imitated and even exceeded the monumental scale of the architectural ensembles in the Ilkhanid capitals of Tabriz and Sultaniyya. In an attempt to ensure the continuity of the Timurid dynasty, Timur’s successors adopted Yuan iconography and visual vocabulary so as to forge an ancestral and artistic genealogy that directly related the Timurids with the Mongols via the aesthetic legacy of the Ilkhanids and the Yuan. Their cultural production thus secured the continuity of the Timurid royal patrons as just successors of Chinggis Khan.

Keywords

Timurid architecture, Mosque, Samarqand, Ilkhanid, Yuan, Ming

This article was received on 11 July 2022 and published on 9 October 2023 as part of Manazir Journal vol. 5 (2023): “The Idea of the Just Ruler in Persianate Art and Material Culture” edited by Negar Habibi.

Introduction

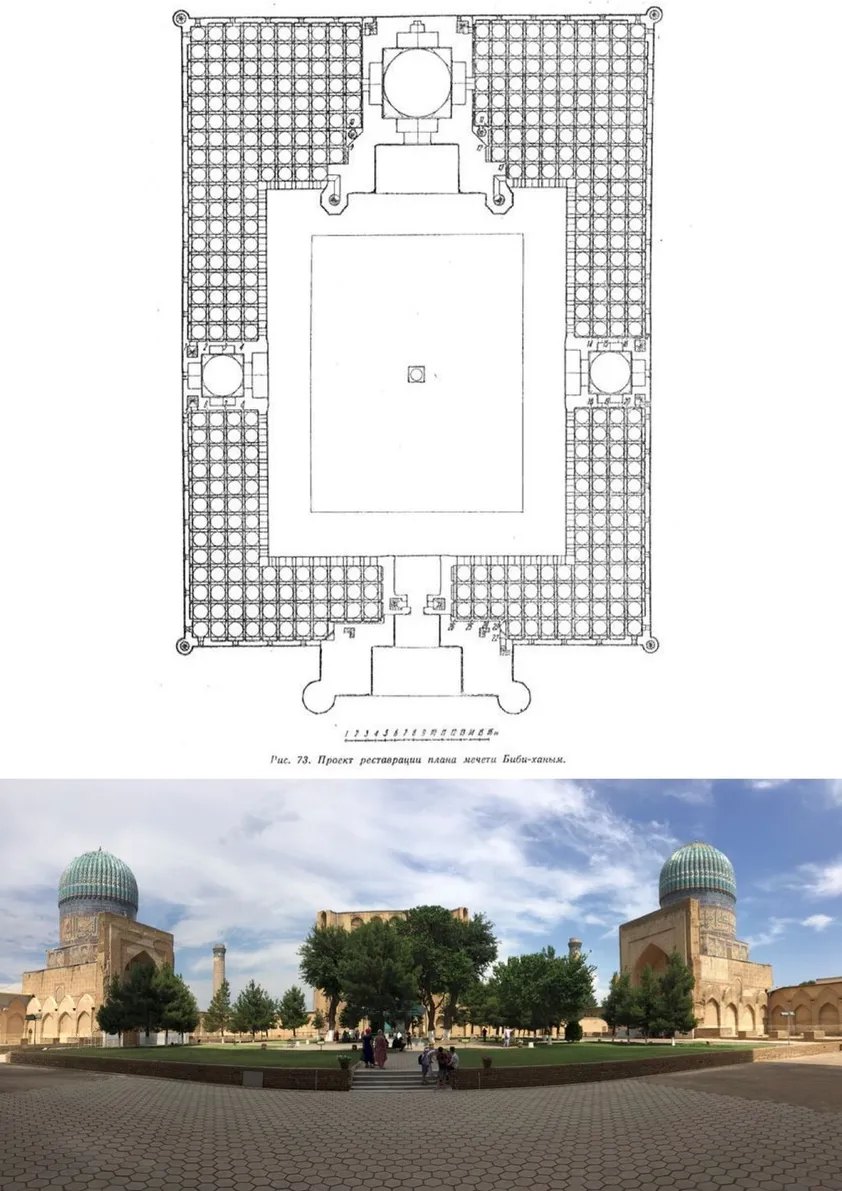

The Bibi Khanum Congregational Mosque founded in May 1399 in Samarqand was conceived as the most monumental expression of Timur’s rule (1370-1405). The mosque (fig. 1) was the greatest building project initiated during Timur’s lifetime and still stands today, having been restored in the 20th and 21st centuries. It is unlikely that Timur saw its completion as he died several months after the foundations of the main entrance portal were restructured. Undoubtedly, the building was completed under Timur’s successors in the first half of the 15th century. This essay explores the architecture of the mosque as a representation of Timurid legitimacy related to Ilkhanid architectural prototypes in Sultaniyya and Tabriz on the one hand, and as an epitome of Timurid continuity by evoking Yuan iconography attested by the cultural exchanges between the Timurid and the Ming courts under Shah Rukh (r. 1409–1447) on the other. More specifically, this article focuses on the construction of the mosque under Shah Rukh’s eldest son and governor of Samarqand, Ulugh Beg (r. 1409-1449) as an expression of his ambition for supreme legitimacy in Transoxiana. The mosque is analysed as Ulugh Beg’s attempt to forge ancestral and artistic genealogy that directly related the Timurids and the Mongols via the aesthetic legacy of the Ilkhanids and the Yuan, thus securing the continuity of the Timurid empire as just successors of Chinggis Khan. After 1409, Shah Rukh moved the Timurid capital to Herat and Samarqand was attempting to preserve its primary role as a cultural and architectural centre across the vast Timurid realm.

The architecture of the mosque has been discussed by several scholarly studies (Masson and Pugachenkova, Bibikhonim, “Shakhri”; Ratiia; Pugachenkova; Man’kovskaia; Barthold,1 Four studies, “Mechet’ Bibi-Khanym”, “O pogrebinii Timura”; Pinder-Wilson; Golombek and Wilber; Lentz and Lowry; Hillenbrand; Bulatova and Shishkina) that have all stressed on its monumentality. The massive scale of the Bibi Khanum Mosque has always been associated with Timur’s struggle for power and legitimacy as the studies focus on the grandiose imagery found in both architectural projects or ruthless military deeds (Lentz and Lowry 36; Manz, “Tamerlane’s Career and Its Uses”). Although envisioned during Timur’s lifetime as the most significant building in the capital Samarqand, Timur did not live long enough to see the mosque’s completion. Moreover, Timur may not have witnessed the final stages of the other two monumental structures usually associated with his rule: the Yasawi Shrine in Turkistan (present-day Kazakhstan) and the Aq Saray Palace in Shahr-i Sabz (present-day Uzbekistan). Based on their epigraphy and exterior decoration, the completion of both monuments can be attributed rather to the 1420s. The only surviving memorials that were completed under Timur are one or two-chamber mausoleums which were built on a considerably smaller scale. In this sense, the monumentality of the Bibi Khanum Mosque may have been ascribed to Timur by contemporary historiography (Ibn ʿArabshah; Yazdi2) and travelogues (Clavijo) in order to magnify his persona as a dynastic founder. However, the architectural evidence points out at a later completion date and most certainly to an iconographic programme developed by Timur’s successors in the first half of the 15th century.

Timurid Samarqand at the Turn of the 15th Century

The great Central Asian ruler Timur (ca. 1336-1405), known in the west as Tamerlane, was the embodiment of Eurasian identity. Through political and military action, Timur created a vast empire that extended from Anatolia to India in the 14th and 15th century. He is also one of the few mortals to have given their name to a distinct architectural style that was developed by his successors on the territories of present-day Afghanistan, Iran, Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan. Labelled by architectural historians as “metropolitan Timurid,” this style is characterized by symmetrical open courtyard compounds with two or four iwans (monumental vaulted portals), large ribbed double-shell domes on high drums, extensive epigraphic programmes both in the interiors and exteriors of all structures using a variety of calligraphic scripts ranging from colossal geometric or floral Kufic to monumental thuluth.3 The exteriors were decorated with polychrome revetments utilizing almost all artistic techniques used in Islamic architecture such as glazed and unglazed brick, tile mosaic, cuerda seca, carved terracotta and majolica.

Timur aimed to recreate the Mongol empire and gain supremacy over the Islamic world. Although he was a member of the tribal aristocracy, he was neither a direct descendant of Chinggis Khan, nor a chief of his own tribe, the Barlas, who lived in Shahr-i Sabz. Without either of these mandates, Timur could not obtain the title of a khan, a symbol of sovereignty in the steppe, and could not become a caliph, the supreme spiritual leader of the Islamic realm (Manz, “Tamerlane’s Career” 3). Through dynastic marriages to Chinggisid princesses, Timur gained the title of a royal son-in-law (Mongolian güregen) and ruled on behalf of appointed Chinggisid puppet khans who had little ceremonial authority. Timurid historiography represented him as a supreme leader initiating enormous building projects and a ruler with supernatural powers; he was referred to as Sahib Qiran meaning lord of the auspicious conjunction (Chann; Moin). Timur’s quest for legitimacy has been widely discussed in the seminal works of Beatrice Forbes Manz (The Rise and Rule; “Tamerlane’s Career”; Power, Politics and Religion) and John Woods (“The Rise of Tīmūrid Historiography”; The Timurid Dynasty; “Timur’s Genealogy”). Here, I would like to focus on the attempts of Timur’s grandson Ulugh Beg to justify, and at the same time, underline the Mongol lineage of his rule in Samarqand at a time when the main capital of the empire had been moved to Herat.

Ulugh Beg was the eldest son of Shah Rukh (1377-1447) and Gawhar Shad Agha (1376-1457). Neither of his parents was of a Chinggisid descend. Shah Rukh was born by the Timurid concubine Taghay Tarkan Agha Qarakhitay (Woods, The Timurid Dynasty 19); Gawhar Shad was the daughter of the Timurid amir (military leader) Ghiyath al-Din Tarkhan, whose ancestor had obtained the honorific title of Tarkhan from Chinggis Khan for saving his life (Barthold, Four Studies 43; Manz, “Gowhar-Shad Agha”). Gawhar Shad was a competent ruler and the most renowned female building patron of the Timurid dynasty (Arbabzadah). All of her three sons, Ulugh Beg (1394-1449), Baysunghur (1397-1433) and Muhammad Juki (1402-1445) were intellectuals and patrons of the arts who left their profound legacy in the major Timurid cities of Samarqand, Herat and Shiraz respectively.

Ulugh Beg’s name at birth was Mirza Muhammad Taraghay but very soon he received the Chaghatay designation Ulugh Beg meaning “Great Prince.”4 According to Barthold, this Turkic title was used only for Timur, who was called beg and ulugh-beg meaning The Great Amir (Four Studies 44). It is not clear why Shah Rukh’s son was given a title that could have been borne only by Timur. Ulugh Beg was born on 22 March 1394 in Sultaniyya in the ughruq (family camp) of Timur’s chief Chinggisid wife Saray Malik Khanum, who stayed for eleven months in the former Ilkhanid capital during Timur’s five-year military campaign. Additionally, between 1400-1401 and 1402-1403 the queens and the princes lived for a long time in Sultaniyya (Barthold, Four Studies 45). The young boy was entrusted to Saray Malik Khanum’s care and most likely remained with his queen guardian until Timur’s death in 1405 (Four Studies 47).

Saray Malik Khanum was a Chinggisid princess and daughter of the Chaghadayid Khan Qazan who controlled huge areas of Khurasan in the 13th and 14th centuries. At first, Saray Malik Khanum was married to Amir Husayn, the supreme amir of the Chaghatays with a residence in Kabul and later in Balkh. In 1370, Timur dethroned Amir Husayn and was declared the sovereign governor of the Chaghatay Ulus. Amir Husayn was killed and Saray Malik Khanum became Timur’s primary wife, who enjoyed exclusive rights and respect in the Timurid family. However, Saray Malik Khanum was most certainly older than Timur and she had passed the childbearing age by 1370. The other Chinggisid wife whom Timur married in 1378, Tuman Agha, was the daughter of Qazan Khan’s son, Amir Musa, the brother of Saray Malik Khanum; she also remained childless. It was only on the account of these dynastic marriages to Chinggisid princesses that Timur could use the title of güregen that secured him the mandate required in order to rule across Transoxiana and Khurasan. Yet neither of Timur’s Chinggisid wives bore him any children which makes the attempts of Timur’s descendants to fabricate a Chinngisid lineage even more significant.

Timur consolidated his power in 1370 and chose Samarqand, an important trading hub along The Silk Road, as the capital of his growing empire. Samarqand is one of the oldest cities in the world situated in the Zarafshan Valley on the territory of present-day Uzbekistan. During the time of the Achaemenid empire (c. 550-330 BC), Samarqand was the capital of the Sogdian governors and merchants, who continued to control the trade routes from Imperial China to Byzantium until the 11th century. In 329 BC Samarqand was conquered by Alexander the Great and adopted the Greek name Marakanda. Subsequently, the city was ruled by a succession of Iranian and Turkic dynasties and by the 10th century had a population of approximately 500,000. Until the Mongol invasion by Chinggis Khan in 1220, Samarqand was a thriving urban centre with thousands of craftsmen and prolific building activity. The Mongol armies devastated the cultural layers accumulated by previous dynasties causing the city to lose, for about a century, its primary economic and artistic importance in Transoxiana.

Unlike his Mongol predecessors, Timur was focused on establishing control over the sedentary territories; the cities were his targets. In all subjugated lands he founded permanent garrisons and military strongholds, assigning governorships to individuals from among his family or loyal amirs with the governors being responsible for the enforcement of taxation on the settled populations. Thus, with an immense wealth flowing toward the newly designated capital from levy and war spoils, Timur had the means to construct an ostentatious capital city. From across all conquered provinces and urban centres, he summoned the most skilful craftsmen and artisans to Samarqand. The site to the south of the old Afrasiyab elevation was designated as the new Timurid city that quickly developed into a monumental capital. Despite the splendour of all new constructions, the court life took place in the verdant quadripartite gardens surrounding Samarqand (Golombek, “The Gardens of Timur” 141). In order to augment the importance of his capital and to profess its opulence, Timur surrounded it by villages bearing the names of the largest Islamic capitals: Sultaniyya, Shiraz, Baghdad, Damascus and Cairo (Barthold, Four Studies 41). By 1404 Samarqand had one hundred fifty thousand citizens (Clavijo, Embassy to Tamerlane 288). Timur employed architecture and new urban solutions as a tool to legitimize his rule on a grand scale and to assert himself as an heir to major Islamic empires.

The Construction of the Bibi Khanum Mosque

According to detailed information provided in the historiographic sources by Ibn ʿArabshah, Yazdi and Clavijo, at the end of the 14th century, Timur spent his vast resources on a new Friday mosque to the south of the Iron gate in Samarqand. Timur began the construction of the Bibi Khanum Mosque after his military campaign in India; the monument meant to commemorate his conquest of Delhi. Timur set out on his India campaign in March 1398 and gloriously returned to Samarqand in April 1399. Based on the political link to India and the architectural similarities, some scholars (Welch and Crane; Golombek and Wilber 259) have attributed the design of the Bibi Khanum Mosque to the Jahanpanah Mosque in Delhi, which is also based on the four-iwan plan, the chosen architectural layout for Timur’s own congregational mosque (fig. 2a). Although researchers usually refer only to the Delhi mosque with domed structures behind the iwans, the compound was much larger and consisted of a madrasa, an additional mosque in the north section, and the mausoleum of Firuz Shah Tughluq (1351-1388). The complex was built during the reign of Muhammad Shah Tughluq (1325-1351) or perhaps his successor, Firuz Shah (r. 1351-1388).

This possible Indian artistic inspiration is additionally attested by period sources. A native of Damascus, Ibn ʿArabshah (d. 1450) was captured by Timur in 1400 and brought to Samarqand; he wrote the scathing history of Timur’s rule. Although Ibn ʿArabshah stayed in the capital only for eight years, his eyewitness rendering of the last years of Timur’s reign and subsequent dead provide a vivid description of the events:

Timur had seen in India a mosque pleasant to the sight and sweet to the eye; […] and being greatly pleased with its beauty, he wished that one like it should be built for him at Samarkand, and for this purpose chose a place on level ground and ordered a mosque to be built for himself in that fashion and stones to be cut out of solid marble […]. (222)

The campaign in India was indeed a huge military and political success for Timur, who brought back with him not only skilled workers from Hindustan but also ninety-five elephants that drew enormous carts transporting the massive stones with which the Bibi Khanum Mosque was to be constructed. The stones were used for the 480 columns, each seven gaz (cubits) high, which would support the shallow domes of the gallery around the main courtyard; initially the gallery was supposed to have two storeys (Man’kovskaia and Tashkhodzaev, “Novye istoriko-arkhitekturnye” 54). Carved stone was applied in the decoration of the main portal and the dome chamber. The Timurid court chronicle, the Zafarnama (Book of Victory), by Sharaf al-Din ʿAli Yazdi, completed in 1425, (Woods, “The Rise of Tīmūrid Historiography” 100) sheds more light on the auspicious commencement date of the large-scale project and the manpower required for its completion:

On Sunday, the fourteenth of the blessed month of Ramadan in the year 801 […], the most skilful engineers and well-trained masters, at the lucky moment and most propitious time, laid its foundations. The workers and dexterous artisans, each one of which was the master craftsman of his country and unique in his realms, made manifest the subtitles if ingenuity and skill in constructing foundations and lending strength to the structure. Two-hundred men worked inside the masjid itself, such as the stone-gravers of Azerbayjan, Fars, and Hindustan; and five-hundred persons were constantly in the mountains, cutting stone to be transported to the city. The various types of craftsmen and artisans who had been gathered in the capital from all parts of the inhabited world, each one in his own assignment laboured to his utmost capacity. (Golombek and Wilber 258)

According to the description of the Bibi Khanum Mosque in Maṭlaʿ-i saʿdayn va majmaʿ-i baḥrayn (The Rise of the Two Auspicious Constellations and the Junction of the Two Seas) presented by ʿAbd al-Razzaq Samarqandi (1413-1482) quoted in Yakoubovsky (279), masters from Basra and Baghdad modelled the maqsura, the sufas and the courtyard after structures in Fars and Kirman. Silk carpets covered the open spaces. Craftsmen from Aleppo lit gilded lamps similar to heavenly stars in the inner domes of the mosque (Yakoubovsky 280).

The new site chosen and cleared for the mosque (Clavijo, Embassy to Tamerlane 280) could accommodate its monumental dimensions with an open courtyard measuring 109 meters wide and 167 meters long that could hold up to ten thousand worshippers. The building is based on the four-iwan plan (fig. 2a and fig. 2b). The four-iwan scheme, marking the four cardinal points with vaulted iwans surrounding a rectangular open courtyard, has been traced back to the Parthian palaces of Assur (Pope 30) and is associated with the Sasanian period (224 BC-651 AD) (Ardalan 70). Originally, the scheme was used as a palace plan representing royal and divine power. Later, with the advent of Islam and after the 10th century, the four-iwan plan was widely adopted for religious compounds such as mosques, madrasas, caravanserais, and domed khanaqahs (Sufi lodges).

Following the palace and madrasa architectural examples of the Seljuks (1037-1307), the Qarakhanids (the Turkic ruling dynasty of Central Asia between 999-1211 with Samarqand as their capital) and the Ilkhanids who all built four-iwan royal monuments, Timur may have chosen the four-iwan plan in order to embody his ambitions of an heir to the glorious Islamic empires. The four iwans of the courtyard marked ideally the four corners of the world that were also signified by the four corner minarets.

It is unlikely that Timur would have envisaged the overall architectural design and epigraphic programme of a monument that could not directly contribute to his claims for imperial rulership across Iran and Turan. It is also plausible to look for architectural prototypes within the Ilkhanid capitals that may have influenced the Timurid architectural iconography throughout his reign. The Ilkhanids, who were descendants of Chinggis Khan, ruled Iran and the adjacent lands in Iraq and Anatolia from 1256 to 1335. In view of his endeavours to revive the Mongol empire and to present himself as a legitimate heir to Chinggis Khan, Timur may have followed Ilkhanid architectural paradigms.

In particular, the Congregational Mosque of Bibi Khanum can be analysed in connection with Ilkhanid mosques and mausoleums, erected in the capitals of Tabriz and Sultaniyya. Tabriz was the royal capital of the Ilkhanid ruler Ghazan Khan (r. 1295-1304) who converted to Islam in 1295 (Melville). Sultaniyya was the capital of his brother and successor Uljaytu (r. 1304-1316). The architectural heritage of these Ilkhanid sultans, who were born Christian, and ruled in Iran in the late 13th to early 14th centuries, bridges the artistic vocabulary of Byzantine and Islamic architecture (Askarov 30-40).

Aspiring to surpass the monumentality of the Ilkhanid capitals posed technological problems to the Timurid builders. Although the Bibi Khanum Mosque had the largest dome span in the history of Islamic architecture, according to Ibn ʿArabshah (223), the mosque was left in ruins after Timur tried to increase the height of its main entrance.

After Timur came back to Samarqand in the autumn of 1404, he found out that the main portal of his mosque was lower than the portal of the adjacent madrasa built by Saray Malik Khanum, his chief wife. Timur immediately ordered the restructuring of the entrance iwan and demanded for deeper foundations to be dug. He was fervently supervising the building activities. However, Clavijo describes the health of Timur at the time (November 1404) as very fragile:

The Mosque which Timur had caused to be built […] seemed to us the noblest of all those we visited in the city of Samarqand, but no sooner had it been completed than he began to find fault with its entrance gateway, which he now said was much too low and must forthwith be pulled down. […] Now at this season Timur was already weak in health, he could no longer stand for long on his feet, or mount his horse, having always to be carried in a litter. […] Thus the building went on day and night until at last a time came when it had perforce to stop […] on account of the winter snows which began now constantly to fall… (By November) His Highness was in a very weak state, having already lost all power of speech, and he might be at the very point of death […]. (Embassy to Tamerlane 284)

Timur died shortly afterwards, allegedly on 18 February 1405 in Otrar. Given his poor health and the harsh winter of 1404, it is quite unlikely that the Bibi Khanum Mosque could have been completed under his reign. Judging by the dilapidated state of the remains in the late 19th century (fig. 1), we can assume that the surviving structures—the main portal and the three domed units—were undoubtedly constructed under Timur’s successors.

The most likely royal patron to have taken over the completion of the Friday mosque, was Timur’s grandson Ulugh Beg who was proclaimed governor of Samarqand by his father Shah Rukh in 1409. Any building activity throughout the fight for succession (1405-1409) is rather improbable as the years were characterized by a depletion of the royal treasury and chaotic struggles for power within Timur’s immediate family.

Ulugh Beg reigned for forty years in Samarqand and was able to secure a safe environment in which the city flourished, allowing for several major building projects to be accomplished. The only direct reference that links Ulugh Beg with the Bibi Khanum Mosque is the monumental Quranic stand that adorns the centre of the courtyard since 1875 (fig. 3). The stand was commissioned by Ulugh Beg and was initially placed in the main sanctuary (Ratiia 32). The text reads: “The great sultan, merciful khagan, patron of the faith, guardian of the Hanafi madhab, the purest sultan, son of a sultan, himself son of a sultan, satisfier of the world and the faith, Ulugh Beg Gurgan” (Lapin’ 9).5

The stand was most likely erected for the largest, and unfortunately, dispersed copy of a monumental Quran, often attributed to Baysunghur, but likely created by the calligrapher ʿUmar ʿAqta (Ahmad 64). Each page measuring 1.7 by 1 meter contains seven lines of text in the muhaqqaq script which covers only one side of the heavy sheets which were locally produced by ladling pulp into floating moulds resting in water (Bloom 67). The Quran was thus very heavy and had to be transported with the aid of a cart.

Ulugh Beg is believed to have memorized the Quran with all seven variant readings. His Quranic stand as a material expression of piety is made of carved stone in relief and clearly bears his name. Its rich arabesques and poly-lobed details can be attributed to the iconography of Yuan porcelain prototypes that may have entered the Timurid court via the active caravan trade between Central Asia and China. With this in mind, China should not be regarded only as a trade partner as it was the home of the Yuan dynasty (1271-1368) established by Kubilay Khan (d. 1294). Although Chu Yüan Chang, a humble plebeian turned general, succeeded in overthrowing the Mongol dynasty in 1368 and proclaimed himself as emperor, taking the title of Hung Wu (1328-1398), the significance of the Yuan legacy for the Timurids should not be underestimated. Under Timur, there were several embassies to Ming China. Even though the exchange of royal gifts and the intensity of the trade relations increased under Shah Rukh and Ulugh Beg (Roxburgh, “The Narrative of Ghiyath al-Din Naqqash”), the first Timurid embassy arrived in China in 1387, followed by yearly tributes of horses and camels to the Ming court. The first known Chinese embassy to Timur was established in 1395. The Ming chronicles, Ming Shi and the Ta Ming i tʿung, and the Ming Geography Shi Si yü ki refer to Samarqand as the “city of abundance”, and mention “a beautiful building set apart for prayer to Heaven” situated in the north-eastern part of the city.6 It is highly probable that they refer specifically to the Bibi Khanum Mosque which had pillars of “tsʿing shi (blue stone), with engraved figures.” Even today, the stone of the Quranic stand has a blue-greyish tinge to it. According to the chronicles, “there is in this building a hall where the sacred book is explained. This sacred book is written in gold characters, the cover being made of sheep’s leather” (Bretschneider 258-270). The fact that the Ming chronicles explicitly mention the location of the richly-decorated mosque and refer to a particular Quran, only stress the importance of their artistic qualities and their symbolic association with the rulers of Samarqand.

Stylistic Ilkhanid Prototypes of the Domed Sanctuaries at the Bibi Khanum Mosque

The primary architectural innovation in the Bibi Khanum Mosque is its open courtyard compound and three domed sanctuaries: the largest one to the west constitutes the main mosque with two smaller units to the north and to the south; the exact function of these lateral chambers has never been identified (Ratiia 31). The main sanctuary contains the qiblah (prayer wall towards Mecca) and the mihrab (prayer niche) situated on the longitudinal axis. However, the qiblah of the Bibi Khanum Mosque is not ideally oriented towards Mecca. One argument for this orientation can be traced back to Babur who discusses the orientation of the qiblah of the Ulugh Beg Madrasa in Samarqand and mentions that it differs “greatly” from the orientation of the Muqatta’ Mosque, the latter of which was determined astronomically (Thackston, The Baburnama 58). The qiblah orientation of the Ulugh Beg Madrasa is almost parallel to the orientation of the Bibi Khanum Mosque (the difference between the two is about two degrees). Thus, the orientation of the main compositional axis can be related to other royal building projects in Samarqand constructed under Ulugh Beg.

The architectural design of the Bibi Khanum Mosque is unique not only because of its Timurid architecture, but also because it remains the earliest mosque compound in the Islamic world with three separate domed units. Each unit is based on a square cruciform plan with a domed interior defined by four axial arched recesses with double-shell domes resting on high cylindrical drums.

For the first time in a Timurid building, the main mosque is situated along the longitudinal axis. The earliest surviving example of such an arrangement, within a four-iwan plan, is the Ilkhanid Congregational Mosque at Varamin (commissioned 1322-1323, completed 1325-1326), in which the domed sanctuary dominates the whole compound (Komaroff 121-123). The concept of a prayer hall with a prayer niche opposite the main entrance was utilized already in Umayyad and Abbasid mosques (Blair, “Ilkhanid Architecture” 74).

In late 1404 Timur resided at the madrasa of Saray Malik Khanum while he was supervising the construction of the Bibi Khanum Mosque (Thackston, A Century of Princes 90). The madrasa of his chief Chinggisid wife was situated across the road from the mosque, with their main entrances symmetrically arranged along the new trading route that connected the Iron gate of Samarqand with the new bazaar (Registan) at the beginning of the 15th century. The madrasa was completely destroyed by the Amir of Bukhara ʿAbdullah Khan II at the end of the 16th century (Man’kovskaia and Tashkhodzaev, Bibikhonim 15) and only the mausoleum survived (Zakhidov 71). According to the reconstruction suggested by Ratiia (14), the madrasa was based on the four-iwan plan and was similar in scale with the mosque. Furthermore, Ratiia proposes that the mausoleum was situated along its perpendicular axis and incorporated into the centre of the southern wall. Zakhidov disagrees with this statement and points out the obvious disparity that the perpendicular axis of the madrasa would have stretched beyond the city wall. The present urban situation proves that the madrasa was much smaller in scale and the remaining mausoleum was most likely along its longitudinal axis (fig. 4).

It is very difficult to determine exactly the plan of the madrasa, yet given its smaller scale, it is rather unlikely that it followed the four-iwan scheme. It is believed that Saray Malik Khanum herself was buried in the madrasa (Zakhidov 60-61). However, the female burials discovered at the Bibi Khanum Mausoleum in 2005 were of a later date. The trend of a domed funerary chamber within a royal madrasa was continued down into the 15th century in Khurasan, where the majority of the nobles in the court of Herat were buried in madrasas that they commissioned themselves (O’Kane, Timurid Architecture in Khurasan 21).

Based on the orthogonal proximity of the two buildings, we can conclude that the Bibi Khanum Mosque formed a kosh with the Saray Malik Khanum Madrasa. The kosh is an architectural ensemble of two or three buildings oriented towards each other with their main façades, generally symmetrically aligned along the same axis, forming a square between them. The earliest example of a kosh in Samarqand is from the 11th century and is comprised of the four-iwan Qarakhanid royal madrasa from 1066 built across from the gurkhana (burial chamber) of the Qutham Abbas shrine at Shah-i Zinda (Nemtseva). It may be possible that the Timurids imitated the compositional principle of the kosh in order to stress the continuity of their Turkic empire on the territory of Transoxiana.

Additionally, there are two important similarities between the Bibi Khanum Mosque and the architecture of Ilkhanid capital of Sultaniyya. The first is that Uljaytu’s Congregational Mosque was built as a kosh across from the madrasa of his favourite wife (Blair, “The Mongol Capital” 145-146). In 1385, Timur occupied Sultaniyya, which was proclaimed capital by Uljaytu in 1304. It is very likely that Timur was familiar with the remains of the monumental Congregational Mosque which did have a four-iwan plan and a domed sanctuary along the main longitudinal axis if we follow the descriptions by the 17th century travellers Olearius and Struys. The latter was depicted by Matrakçı (1537-1538), Istanbul University Library, Yildiz T 5964. fol. 32r (fig. 5).

According to Rogers, Timur “admired” Uljaytu’s mosque and Timur’s architects might have been inspired by it (21). Further Rogers suggests that the Sultaniyya Mosque “was the prototype” of Bibi Khanum (21). To prove his argument, he analyses the similarity between the entrance iwan of Uljaytu’s mosque flanked with polygonal minarets as drawn by François Préault in 1808 (fig. 6 left) and the impressive sanctuary iwan of Timur’s mosque with its massive octagonal pylons (Rogers 21). In the Samarqand mosque, the main sanctuary is flanked by enormous decagonal socles and shafts (fig. 6 right). Agreeing with Rogers, Blair comments that “the portal of Uljaytu’s mosque at Sultaniyya, known only from drawings by Préault and others, closely resembles the portal of the mosque of Bibi Khanum” (Monumentality 151).

To recapitulate, both Timur and Uljaytu’s royal kosh ensembles consisted of a mosque based on the four-iwan plan and a madrasa; the main mosque sanctuary with a high qiblah dome was located along the longitudinal axis and both mosques had monumental projecting entrance arched portals with double buttress minarets. The compounds were paved and covered with multiple small domes above the galleries.

The second similarity originates in the complex around Uljaytu’s mausoleum (1304-1313) which was also organised according to the four-iwan plan, whereby the iwans were connected by arcades around the courtyard and the tomb was situated in the south iwan (Blair, “The Mongol Capital” 144). Blair stresses the fact that Uljaytu’s tomb complex followed the four-iwan plan of the Tabriz tomb complexes of Ghazan (d. 1304) and Rashid al-Din (d. 1318). According to Olearius and Struys, there were an adjacent khanaqah and a madrasa.

In Timur’s Congregational Mosque, the corners of the rectangular compound are defined by four minarets. Sharaf al-Din ʿAli Yazdi describes them in his chronicle: "In each of the four corners is a minaret, whose head is directed toward the heavens, proclaiming: ‘Our monuments will tell about us!’ which reaches to the four corners of the world" (Golombek and Wilber 259). Furthermore, the two monumental gates—the entrance iwan and the sanctuary iwan—are both flanked by imposing buttress-like minarets bringing the total minarets to eight. The eight minarets of the Bibi Khanum Mosque (fig. 7) might metaphorically correspond to the eight minarets of Uljaytu’s mausoleum.

Blair discusses the latter as a representation of Uljaytu’s striving for broader power and authority as a protector of the Holy Cities and a leader of the Islamic world, whereby multiple minarets were interpreted as a reference to the holiest sanctuaries of Islam (Blair, “The Epigraphic Program” 72). The particular orthogonal organization of the three domed sanctuaries with an open courtyard compound, so characteristic of the Bibi Khanum Mosque, can be also traced back to Ilkhanid architectural examples in Tabriz.

The funerary complex of Ghazan Khan, the Ghazaniyya in the southern district of Shanb in Tabriz, consisted of a hospice, hospital, library, observatory, academy, fountain, pavilion, and two madrasas (Wassaf 382-384; Blair and Bloom 6; Wilber 124). According to Rashid al-Din, the idea of this complex known as the Gates of Piety came to Ghazan after he visited the shrines of Bastami and ʿAli (Kamola 92). The tower-mausoleum had a twelve-sided plan and was crowned by a dome (Godard 263). Wilber visited Tabriz in the 1930s and has reconstructed the mausoleum based on his measurements and on the contemporary (14th century) accounts of Ibn Battuta and Wassaf (124-126).

Analysing a miniature from Rashid al-Din’s Jamiʿ al-Tawarikh (BnF Supplément Persan No. 1113, 256v-257r), Wilber argues that Ghazan’s mausoleum was flanked by a domed madrasa (to the left) and a domed khanaqah (to the right) (fig. 8).7 All three domed buildings were arranged around a central courtyard. This appears to be what Ibn Battuta describes as well: “We were lodged in a place called Shām where the tomb of Ghāzān…is located. Adjacent to this tomb is a splendid religious school (madrasa) and a monastery (khanaqah) where travellers are fed” (quoted by Wilber 125). Thus, we can conclude that the central complex of the Ghazaniyya consisted of three domed structures: the main mausoleum on the longitudinal axis, the khanaqah and the madrasa on the perpendicular axis forming most likely a kosh. This solution of three domed compounds oriented along two orthogonal axes is almost identical with the plan of the Bibi Khanum Mosque and the position of its domed chambers.

The Timurid dynastic ensemble of Gur-i Amir (late 14th century to 1440s) follows the same architectural configuration: the octagonal tomb, in which Timur was subsequently buried, is situated along the longitudinal axis to the south; the two-iwan, two-storey madrasa to the east and the domed cruciform khanaqah to the west are located along the perpendicular axis. It is highly probable that the Gur-i Amir complex also followed the architectural plan of the Ilkhanid mausoleums in Tabriz and Sultaniyya.

The khanaqah as part of the funerary complex testifies the elevated status of Sufism at the beginning of the 14th century. Blair notes that “in Iran, Sufism had become an institutionalized practice linked to government” (Blair, “Ilkhanid Architecture” 79). Similarly, Sufism was institutionalized during Timur’s reign (Askarov 26-29). As a result, royal khanaqahs were commissioned in close proximity to royal (funerary) madrasas. In Herat of the 15th century, many patrons built joint complexes of madrasas and khanaqahs, whereby the teachers were “moving freely from one to the other” (O’Kane, “Poetry, Geometry” 23).

URL: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8427170s.r=Persan%201113%2C?rk=21459;2

Accessed 18 Sept. 2023. Image courtesy of Bibliothèque nationale de France, photographed by Département de la Reproduction.

According to O’Kane, this architectural phenomenon “is strong evidence of the way in which Sufism had penetrated the fabric of Timurid society in Herat” (23). Likewise in Samarqand, the khanaqah-madrasa kosh ensembles were repeated at Gur-i Amir and at Registan Square by Ulugh Beg.

Timur visited Tabriz in 1385 during his campaign in Iran (Rashidzada 472). He went, in particular, to the district of Shamb where the Ghazaniyya was situated, and recited a Quranic verse at the mausoleum followed by a visit to the madrasa and the khanaqah.

The following analysis shows that Timur had first-hand experience with the Ilkhanid monuments in Tabriz and Sultaniyya. His grandson, Ulugh Beg was born in Sultaniyya and, as shown above, spent considerable time at the beginning of the 15th century in the city in the family camp of Timur’s chief Chinggisid wife Saray Malik Khanum. Appropriating the architectural monumentality of the Ilkhanid capitals in the Timurid stronghold of Samarqand would have reinforced the Timurid claims as just heirs to the Mongol Empire.

Epigraphic Parallels between Ilkhanid and Timurid Royal Patronage

Timur saw himself as a reviver of the Mongol Empire. Accordingly, his successors might have copied Ilkhanid royal epigraphic programs in order to stress the continuity between the Timurid and the Mongol empires. I would like to focus here on very specific references to ʿAli that may have reinforced Timurid claims for just rulership across the Islamic world.

The genealogical references connecting Timur to ʿAli can be attested only in the extensive Timurid genealogy presented at Gur-i Amir. There is one inscription on the marble plinth over the tomb in the crypt, superseded by a lengthy religious text, and one on the jade cenotaph in the main mausoleum (Semenov, “Nadpisi na nadgrobiiakh”, vol. 2, 49-62; “Nadpisi na nadgrobiiakh”, vol. 3, 45-54). The latter must have been created after 1425 when Ulugh Beg brought the jade piece from Mongolia in 1424, i. e. about twenty years after Timur’s death (Woods, “Timur’s Genealogy” 85). A partial English translation of the inscription reads:

[…] And no father was known to this glorious (man), but his mother (was) Alanquva. […] She conceived him through a light which came into her from the upper part of a door and it assumed for her the likeness of a perfect man.8 And it (the light) said that it was one of the sons of the Commander of the Faithful, ʿAli son of Abu Talib […]. (Grabar 78)

According to Grabar, these inscriptions can be interpreted as the key to Timurid ideology and legitimization on three different levels (78-79). Firstly, Chinggis Khan and Timur both have the same predecessor, the Mongol Amir Tumananay. Timur descended from Tumananay’s son Kachulay and Chinggis Khan from Tumananay’s other son Kaudy. This lineage directly relates Timur to Chinggis Khan and thus presents him as a legitimate heir to the Mongol Empire. Secondly, Timur’s family tree can be traced down to ʿAli, the son-in-law of the Prophet Muhammad. Through this genealogy Timur’s rule is legitimized across the whole Islamic world. Thirdly, ʿAli is a central figure in the mystical tradition of Sufism which flourished under Timur and his descendants (Muminov 2001). Although Grabar states that “it seems clear that he [Timur] was under strong Shiʿite influences” (79), I argue that the references to ʿAli should not be understood as a Timurid affiliation to Shiʿism. They can be rather seen as part of the Timurid family’s attempts to profess themselves as righteous leaders of the religious community and as the ultimate religious authority across the Muslim world. As summarized by Woods: “linking the houses of ʿAli and Chinggis Khan, this claim combines the two most powerful notions of dynastic legitimacy current in the post-Abbasid, late Mongol Iran and Central Asia” (Woods, “Timur’s Genealogy” 88).

Timur’s shortened genealogy formed part of the foundation inscription of the Bibi Khanum Mosque (Sela 15). It was engraved on the arch of the entrance iwan that partially collapsed during the devastating earthquake on 5 September 1897. These inscriptions were, however, recorded, translated and published by Lapin’ in 1895 (9-10). At present, the entrance iwan has been rebuilt with three parallel pointed arches following the earliest photographs. However, the foundation inscription has not been restored.

Golombek and Wilber have published a translation of the carved stone inscription above the mosque entrance reconstructed by using photographs from the Turkestan Album:

The great sultan, pillar of the state and the religion, Amir Timur Gurgan b. Taraghay b. Burgul b. Aylangir b. Ichil b. al-Amir Karachar Noyan, may God preserve his reign, was helped (by heavenly favor) to complete this jamiʼ in the year 806. (258)

In the Bibi Khanum Mosque, the shahada “There is no God but Allah, Muhammad is the Messenger of Allah” is depicted in Kufic script on the inner side of the vaulted arch of the main entrance and on the rotated square dado. The same inscription can be found on the madrasa in the Ghazan Khan ensemble in Tabriz (fig. 8). According to Wilber, the madrasa is represented to the left of Ghazan’s Mausoleum on Supplément Persan 1113, 256v-257r; the inscription reads (125):

لا اله الا الله محمد رسول الله

There is no God but Allah, Muhammad is the Messenger of Allah

Square Kufic inscriptions reading “ʿAli” executed by glazed brick in the banna-i technique can be found on several Timurid buildings. At the Aq Saray palace at Shahr-i Sabz, “ʿAli” can be seen on the vault of the entrance iwan and at the top of the cylindrical shaft of the northern guldasta. The Kufic on the entrance vault reads “Allah, Muhammad” in light blue glazed brick and “ʿAli” in a stylized frame of dark blue glazed brick. The base of the dome of Uljaytu’s mausoleum is embellished by a circular band comprising trefoils in rectangular Kufic reading “Allah, Muhammad, ʿAli” (Blair, “The Epigraphic Program” 44). This similarity is striking and points to the epigraphic and artistic influences that Ilkhanid monuments might have had on Timurid architecture.

Furthermore, there are at least three other square Kufic inscriptions reading “ʿAli” on the Bibi Khanum Mosque: on the back side of the pylons of the main sanctuary and to the right of the entrance to the sanctuary as a dado reading “Muhammad, ʿAli”. These inscriptions have not been restored, as can be seen on the earliest photographs of the mosque taken by Bogaevskii from the 1870s and by Sarre from around 1900 (Paskaleva, “The Timurid Mausoleum” 185). Unfortunately, the exact position of the inscriptions and their proper organisation in a catalogue has never been published.

Another similarity between the epigraphic programmes of Uljaytu’s Mausoleum and the Timurids, who completed the construction of the Congregational Mosque in Samarqand, is the usage of Surat al-Baqarah (Quran 2). When discussing the monumentality of Bibi Khanum, Babur comments that “the inscription on the mosque, the Koranic verse, ‘And Abraham and Ishmael raised the foundations of the house’ etc., is written in script so large that it can be read from nearly a league away” (Thackston, The Baburnama 57).

Blair detects partially the same inscription in interlaced Kufic around the interior dome at the level of the windows at Sultaniyya: “(And when Abra)ham, and Ishmael with him,/ raised up the foundations of the House:/ ‘Our Lord, receive this from us; Thou art/ (the All-hearing, the All-knowing’)” (Quran 2:127-128; Blair, “The Epigraphic Program” 53). The Throne Verse (Quran 2:255), was also used on the arch of the north portal at Sultaniyya, as well as on the soffit of the east bay in the interior (Blair, “Monumentality” 158). As part of the epigraphic restorations between 1991 and 1996, the two verses of Surat al-Baqarah (Quran 2:127-128) were added on top of the main sanctuary iwan of the Bibi Khanum Mosque (fig. 9). There is no material evidence (archival photographs or prints) that illustrate the original inscription. It was lost prior to the documenting efforts of the Russian archaeologists; the Uzbek restorers used the reference by Babur as a guide (Paskaleva “Epigraphic Restorations” 10).

The square Kufic inscription around the drum of the main sanctuary dome at Bibi Khanum reads لله البقاء (Everlastingness). The same inscription, in a trefoil and repeated five times covers the base of Uljaytu’s exterior dome at Sultaniyya (Blair, “The Epigraphic Program” 44).

All these examples illustrate a carefully crafted genealogy and selection of key epigraphic passages from the Quran used in earlier Ilkhanid royal commissions that have been appropriated to legitimize the Timurid rule beyond the borders of Transoxiana. In the years after Timur’s death and the ensuing struggle for succession, there was an ideological necessity to position the already weakened empire within a context of global rulership. Additionally, Ulugh Beg’s dominion was marginalized when his father Shah Rukh moved the Timurid capital from Samarqand to Herat in 1409. Although the newly crafted genealogy linking Timur to Chinggis Khan, as well as to ʿAli, has been recorded in subsequent literary sources, the only two buildings that actually display it as part of their epigraphic programme are the Gur-i Amir Mausoleum and the Bibi Khanum Mosque. The dating of the inscriptions to 1425 indicates that Ulugh Beg was the royal patron who commissioned them.

Chinese Artistic Influences Introduced by Ulugh Beg

While several authors have translated and commented on the epigraphy of the Samarqand monuments built under Timur and Ulugh Beg (Lapin’; Blair, “Monumentality”), there are surprisingly few studies on the ways that Chinese influenced Timurid iconography. These references can be exclusively observed in the architecture of Samarqand (Borodina, “Dekorativnaia sistema”; Paskaleva, “Remembering the Alisher Navaʾi Jubilee”). These exchanges have been widely described as Islamic Chinoiserie, a process that started much earlier sometime at the end of the 13th century (Kadoi, Islamic Chinoiserie; Crowe “Some Timurdi Designs”; Necipoğlu, “From International Tinurid to Ottoman”). However, the Chinese motifs and craftsmanship techniques were not directly appropriated, and were instead transformed in accordance with local Islamic aesthetics, availability of materials and pigments, and craftsmanship traditions. The westward transmission of Chinese designs was further encouraged by the thriving artistic, political and commercial exchanges between the Ming and the Timurid courts in the first half of the 15th century. These creative endeavours resulted in a sophisticated cultural production across the Turco-Persianate world.

In Samarqand, there are multiple examples of appropriated Chinese iconographic designs in the interior and exterior decoration of the major Timurid monuments built during the first half of the 15th century. Unfortunately, the majority of these artifacts have been either lost or were heavily restored in the 20th and 21st centuries.

According to Borodina, the papier-mâché technique was imported from China and it was applied for the first time in the Bibi Khanum Mosque in Samarqand (“Dekorativnaia sistema” 117). The cotton paper was inexpensive, locally produced and sometimes repurposed for decoration. The architectural details were pressed into ganch (a form of local gypsum) moulds and consisted of seven or eight sheets of paper fixed together with starchy vegetable glue. In addition, papier-mâché was the only decoration applied on the interior domes. Each detail of the relief decoration was separately created and attached with iron nails onto the walls in order to form larger compositions. The upper surface of the papier-mâché ornaments was primed with ganch and gilded; the papier-mâché was used to create a relief surface under the gilding. In separate instances, ganch reliefs pasted over with paper were also applied under the gold surface. Examples of the latter practice can be found not only in the Bibi Khanum Mosque but also in the Tuman Agha Mausoleum at Shah-i Zinda and at Gur-i Amir.

The Samarqand paper was famous for its quality and durability, and was even exported. There were paper mills and storage facilities along the water canals (aryks) coming out of the Siyob bazaar in the north-west of Samarqand. Borodina suggests that the same type of local paper was also used for transferring architectural epigraphy onto the walls. At Gur-i Amir, the papier-mâché was introduced during the redesigning of the main interior in the 1420s; the pre-existing contra relief applied during the first stage of construction (early 15th century) was considered to be “unimpressive” (Borodina, Report C6931 5). Clearly, the usage of papier-mâché can be attributed to the rule of Ulugh Beg, which proves that the interior decoration of the Bibi Khanum Mosque was executed under his patronage by using techniques that could have only developed in Samarqand in the first half of the 15th century.

If we further analyse the traces of interior decoration used in all three domed chambers of the Bibi Khanum Mosque, we can identify the outlines of rectangular arched surfaces framing landscape designs and floral ornaments in blue, yellow and red-brown. The remnants are barely discernible due to fire damage that has caused irreversible loss of the original decoration. In particular, the southern domed chamber was completely redecorated in 2015-2016 (fig. 10 and fig. 11). In this new visual vocabulary, there are freely drawn plant motives and wispy fruit-laden trees arranged in parallel polylobed or star-shaped medallions above the dado. However, it is not very clear whether these were merely transferred from similar decoration from the adjacent Bibi Khanum Mausoleum or based on actual recoded traces found earlier in the mosque.

The interior wall surfaces of the main mosque are also decorated with fine graphic details highlighted in blue over the white stucco surface, including spirals and twelve-pointed stars. We can identify similarities with other buildings erected by Ulugh Beg, such as the Gök Gunbad Mosque in Shahr-i Sabz (1435), and several mausoleums at the Shah-i Zinda necropolis including the Double-dome Mausoleum (known also as Qadi Zada al-Rumi, c. 1430s). Although the Shah-i Zinda mausoleums have been extensively restored in recent years, remains of the cobalt blue spiral ornaments on their white stucco walls and muqarnas vaults can still be discerned.

The above examples were used in the interior decoration of mausoleums and mosques. Although they can be associated with Islamic representations of the abundance of Paradise, their colour schemes and geometry is reminiscent of Chinese lobed and quatrefoil medallions. The appropriation of Yuan and Ming designs in the architectural decoration of the Timurid monuments is a process that started with the arrival of Chinese artefacts into the Timurid artistic workshops and their transformation via the medium of paper into decorative stylized and geometricized patterns which could be quickly executed with the dexterity of a brush. Their inclusion led to a form of decoration that was economical and vibrant.

Conclusion

Although conceived by Timur as the greatest large-scale project in his imperial capital Samarqand, the Bibi Khanum Mosque remained most likely unfinished by the time of Timur’s death in 1405. By analysing the design of the three domed chambers, framing minarets, and gigantic iwans, I have stressed the architectural parallels with major royal commissions by the Ilkhanids in their capitals Tabriz and Sultaniyya. This article also focused on the epigraphy and the Chinese decorative patterns used in the mosque. My main objective was to show that the Bibi Khanum Mosque was probably completed under Timur’s successor and ruler of Samarqand Ulugh Beg in the first half of the 15th century. In order to legitimize his reign and to stage himself as heir to the Mongol empire, Ulugh Beg skilfully combined the monumentality propagated by the dynastic founder and derived from Ilkhanid architectural models with the reinterpretation of Yuan and Ming visual vocabulary. The dynastic ideology coded in his buildings in the form of genealogical inscriptions directly relating Timur to Chinggis Khan and ʿAli justified Ulugh Beg’s mandate to rule. The Bibi Khanum Mosque can thus be interpreted as an artistic manifesto elevating not only the building itself but also the capital of Samarqand as the centre of Islamic rulership beyond the realms of Transoxiana.

Bibliography

Ahmad, Qadi. Calligraphers and Painters: A Treatise by Qadi Ahmad, Son of Mir-Munshi (circa A.H. 1015/A.D. 1606). Translated from Persian by V. Minorsky and from Russian by T. Minorsky, Occasional Papers, 1959.

Arbabzadah, Nushin. “Women and Religious Patronage in the Timurid Empire.” Afghanistan’s Islam: From Conversion to the Taliban, edited by Nile Green, University of California Press, 2017, pp. 56-70.

Ardalan, Nader and Laleh Bakhtiar. The Sense of Unity. The Sufi Tradition in Persian Architecture. University of Chicago Press, 1973.

Askarov, Shukur. Arkhitektura Temuridov. San’at, 2009.

Barthold, Vasilii V. Four Studies on the History of Central Asia. Translated by V. and T. Minorsky, Brill, 1958.

---. “Mechet’ Bibi-Khanym.” Raboty po arkheologii, numizmatike, epigrafike i etnografii. Sochineniia, vol. 4, Izd-vo Nauka, 1966, pp. 116-118.

---. “O pogrebenii Timura”. Raboty po otdel’nym problemam istorii Srednei Azii. Sochineniia, vol. 2.2. Izd-vo Nauka, 1964, pp. 423-454.

Blair, Sheila S. “Monumentality under the Mongols: The Tomb of Uljaytu at Sultaniyya.” Text and Image in Medieval Persian Art, edited by Sheila Blair, Edinburgh UP, 2014, pp. 112-171.

---. “The Epigraphic Program of the Tomb of Uljaytu at Sultaniyya: Meaning in Mongol Architecture.” Islamic Art, vol. 2, 1987, pp. 43-96.

---. “The Mongol Capital of Sultaniyya ‘the Imperial’.” Iran, vol. 24, 1986, pp. 139-52.

---. “Ilkhanid Architecture and Society: An Analysis of the Endowment Deed of the Rab’-i Rashīdī.” Iran, vol. 22, 1984, pp. 67-90.

Blair, Sheila S. and Jonathan M. Bloom. The Art and Architecture of Islam 1250-1800. Yale UP, 1995.

Bloom, Jonathan M. Paper Before Print. The History and Impact of Paper in the Islamic World. Yale UP, 2001.

Borodina, Irina F. “Dekorativnaia sistema vnutrennego prostranstva mavzoleia Guri-Emir v Samarkande.” Istoriia i kul’tura narodov Srednei Azii, edited by B. G. Gafurov and B. A. Litvinskii, Nauka, 1976, pp. 116-23.

---. Report C6931/G-93/l.5-6. Archive of the Department for the Protection of Cultural Heritage. Tashkent, 1965.

Bretschneider, Emil. Medieval Researches from Eastern Asiatic Sources: Fragments Towards the Knowledge of the Geography and History of Central and Western Asia from the 13th to the 17th Century, vol. 2. Kegan Paul, Trench, Truebner & Co., 1910.

Bulatova, Vera A. and Galina V. Shishkina. Samarkand. Museum in the Open. Gafur Guliam, 1986.

Chann, Naindeep Singh. “Lord of the Auspicious Conjunction: Origins of the Ṣāḥib-Qirān.” Iran and the Caucasus, vol. 13, no. 1, 2009, pp. 93-110.

Clavijo, Ruy González. Narrative of the Embassy of Ruy González de Clavijo to the Court of Timour at Samarcand A.D. 1403-6. Translated by Clements R. Markham, Hakluyt Society, 1859. Elibron Classics reprint, 2005.

---. Embassy to Tamerlane 1403-1406. Translated by Guy Le Strange, Harper, 1928.

Crowe, Yolande. “Some Timurid Designs and Their Far Eastern Connections.” Timurid Art and Culture, edited by Lisa Golombek and Maria Subtelny, Brill, 1992, pp. 168-78.

De Angelis, Michele A. and Thomas W. Lentz. Architecture in Islamic Painting. Permanent and Impermanent Worlds. The Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture, 1982.

Godard, André. Die Kunst des Iran. Herbig Verlagsbuchhandlung Walter Kahnert, 1964.

Golombek, Lisa. “The Gardens of Timur: New Perspectives.” Muqarnas: An Annual on Islamic Art and Architecture, vol. 12, 1995, pp. 137-147.

---. “The Paysage as Funerary Imagery in the Timurid Period.” Muqarnas: An Annual on Islamic Art and Architecture, vol. 10, 1993, pp. 241-252.

Golombek, Lisa and Donald Wilber. The Timurid Architecture of Iran and Turan. Princeton UP, 1988.

Grabar, Oleg. Islamic Visual Culture, 1100-1800. Constructing the Study of Islamic Art, vol. 2. Ashgate, 2006.

Hillenbrand, Robert. “Aspects of Timurid Architecture in Central Asia.” Studies in Medieval Islamic Architecture, vol. 2, 2006, pp. 414-453.

Ibn ʿArabshah, Ahmad. Tamerlane or Timur The Great Amir. Translated by J. H. Sanders, Luzac & Co., 1936.

Kadoi, Yuka. “From Acquisition to Display: The Reception of Chinese Ceramics in the Pre-modern Persian World.” Persian Art: Image-Making in Eurasia. Edinburgh UP, 2018, pp. 61-77.

---. Islamic Chinoiserie. The Art of Mongol Iran. Edinburgh UP, 2009.

Kamola, Stefan. Making Mongol History. Rashid al-Din and the Jami' al-Tawarikh. Edinburgh UP, 2019.

Komaroff, Linda and Stefano Carboni, editors. The Legacy of Genghis Khan. Courtly Art and Culture in Western Asia, 1256-1353. Yale UP, 2002.

Lapin’, S.-A. Perevod’ nadpisei na istricheskih’ pamiatnikah’g. Samarkanda. Tipograpfia staba voisk’ Samarkandskoi oblasti, 1895.

Lenz, Thomas W. and Glenn D. Lowry. Timur and the Princely Vision. Persian Art and Culture in the Fifteenth Century. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1989.

Man’kovskaia, Liia Iu. “Novoe v izuchenii mecheti Bibi-Khanym.” Iz istorii isskustva velikogo goroda, edited by G. A. Pugachenkova, Id-vo Gafura Guliama, 1972, pp. 94-118.

Man’kovskaia, Liia and Sh. Tashkhodzaev. “Novye istoriko-arkhitekturnye issledovaniia mecheti Bibi-Khanym.” Arkhitektura SSSR, no. 8, 1970, pp. 54-57.

---. Bibikhonim. Bibi-Khanym. Uzbekiston, 1965 (1968).

Manz, Beatrice Forbes. “Gowhar-Shad Agha.” Encyclopædia Iranica, vol. 11, fasc. 2, pp. 180-181; available online: https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/gowhar-sad-aga. Accessed 27 Aug. 2023.

---. Power, Politics and Religion in Timurid Iran. Cambridge UP, 2007.

---. “Tamerlane’s Career and Its Uses.” Journal of World History, vol. 13, no. 1, 2002, pp. 1-25.

---. The Rise and Rule of Tamerlane. Cambridge UP, 1989.

Masson, Mikhail E. Sobornaia mechet’ Timura izvestnaia pod imenem mecheti Bibi-Khanym. Samarkand, 1929.

Masson, Mikhail E. and Galina A. Pugachenkova. Bibikhonim. Uzbekiston, 1965.

Melville, Charles. “Pādshāh-i Islām: The Conversion of Sultan Maḥmūd Ghāzān Khān”. Pembroke Papers 1, 1990, pp. 159-177.

Moin, A. Azfar. The Millenial Sovereign. Sacred Kingship and Sainthood in Islam. Columbia UP, 2012.

Muminov, Ashirbek and Bakhtiyar Babadzhanov. “Amîr Temur and Sayyid Baraka.” Translated by Sean Pollock, Central Asiatic Journal, vol. 45, no. 1, 2001, pp. 28-62.

Necipoğlu, Gülru. “From International Timurid to Ottoman: A Change of Taste in Sixteenth-Century Ceramic Tiles.” Muqarnas: An Annual on Islamic Art and Architecture, vol. 7, 1990, pp. 136-170.

Nemtseva, Nina B. and Iudit Z. Shvab. Ansambl’ Shah-i Zinda. Istoriko-arkhitekturnyi ocherk. Gafur-Gulyam, 1979.

O’Kane, Bernard. “Poetry, Geometry and the Arabesque Motes on Timurid Aesthetics.” Annales Islamologiques, vol. 26, 1992, pp. 63-78.

---. Timurid Architecture in Khurasan. Mazda Publishers, 1987.

Paskaleva, Elena. “Remembering the Alisher Navaʾi Jubilee and the Archaeological Excavations in Samarqand in the Summer of 1941.” Memory and Commemoration in Islamic Central Asia. Texts, Traditions and Practices, 10th-21st Centuries. Leiden Studies in Islam and Society, vol. 17, edited by Elena Paskaleva and Gabrielle van den Berg, Brill, 2023, pp. 287-329.

---. “The Timurid Mausoleum of Gūr-i Amīr as an Ideological Icon.” The Reshaping of Persian Art: Art Histories of Islamic Iran and Central Asia, edited by Iván Szántó and Yuka Kadoi, The Avicenna Institute of Middle Eastern Studies, 2019, pp. 175-213.

---. “Epigraphic Restorations of Timurid Architectural Heritage.” The Newsletter, no. 64. International Institute for Asian Studies, 2013, pp. 10-11.

Pinder-Wilson, Ralph H. “Timurid Architecture.” The Cambridge History of Iran, vol. 6. The Timurid and Safavid Periods, edited by Peter Jackson and Laurence Lockhart, Cambridge, 1986, pp. 728-758.

Pope, Arthur Upham. Introducing Persian Architecture. Oxford UP, 1969.

Pugachenkova, Galina A. “Vostochnaia miniatura, kak istochnik po istorii architektury XV-XVI vv.” Architekturnoe nasledie Uzbekistana. Izd-vo Akademii Nauk Uzbekskoi SSR, 1960, pp. 111-161.

---. “K voprosu o nauchno-khudozhestvennoi rekonstruktsii mecheti Bibi-Khanym.” Trudy SAGU. Arkheologiia Srednei Azii, 1953, pp. 99-130.

Rashidzada. Babur. I am Timour, World Conqueror. Autobiography of a 14th Century Central Asian Ruler. Dog Ear, 2008.

Ratiia, Sh. E. Mechet’ Bibi-Hanym v Samarkande. Issledovanie i opyt restavratsii. Gos. izd-vo. architektury i gradostroitel’stva, 1950.

Rogers, Michael. The Spread of Islam. Elsevier, Phaidon, 1976.

Roxburgh, David J. “The Narrative of Ghiyath al-Din Naqqash, Timurid Envoy to Khan Baligh, and Chinese Art.” The Power of Things and the Flow of Cultural Transformations, edited by Lieselotte E. Saurma, Monica Juneja, and Anja Eisenbeiss, Deutscher Kunstverlag, 2010, pp. 90–107.

Sarre, Friedrich. Denkmäler persischer Baukunst: geschichtliche Untersuchung und Aufnahme muhammedanischer Backsteinbauten in Vorderasien und Persien. E. Wasmuth, 1901.

Sela, Ron. The Legendary Biographies of Tamerlane. Islam and Heroic Apocrypha in Central Asia. Cambridge UP, 2011.

Semenov, Aleksandr A. “Nadpisi na nadgrobiiakh Tīmura i ego potomkov v Gur-i Emire.” Epigrafika Vostoka, vol. 2, 1948, pp. 49-62.

---. “Nadpisi na nadgrobiiakh Tīmura i ego potomkov v Gur-i Emire.” Epigrafika Vostoka, vol. 3, 1949, pp. 45-54.

Thackston, Wheeler M. A Century of Princes. Sources on Timurid History of Art. Translated, edited, and annotated. The Aga Khan Program for Islamic Architecture, 1989.

---. The Baburnama. Memoirs of Babur, Prince and Emperor. Translated, edited, and annotated, The Modern Library, 2002.

Wassaf, Sharaf al-Din ʿAbd Allah. Ketab-e Mostatab-e Wassaf al-Hazrat dar Bandar-e Moghul. Matbaʿ-e Alishan, 1853.

Welch, Anthony and Howard Crane. “The Tughluqs: Master Builders of the Delhi Sultanate.” Muqarnas: An Annual on Islamic Art and Architecture, vol. 1, 1983, pp. 123-66.

Wilber, Donald. The Architecture of Islamic Iran. The Il Khānid Period. Princeton UP, 1955.

Woods, John E. The Timurid Dynasty. Papers on Inner Asia, vol. 14. Research Institute for Inner Asian Studies, Indiana UP, 1990.

---. “Timur’s Genealogy.” Intellectual Studies on Islam. Essays Written in Honor of Martin B. Dickson, edited by Michel M. Mazzaoui and Vera B. Moreen, University of Utah Press, 1990, pp. 85-126.

---. “The Rise of Tīmūrid Historiography.” Journal of Near Eastern Studies, vol. 46, no. 2, 1987, pp. 81-108.

Yakoubovsky, A.G. “Les artisans Iraniens en Asie Centrale à lʼépoque de Timour.” Art et Archéologie Iraniens, III Congrès International. Izd-vo Akademii Nauk SSSR, 1939, pp. 277-285.

Yazdi, Sharaf al-Din. The History of Timur-Bec. Reprints from the collection of the University of Michigan Library, 2011.

Zakhidov, Pulat Sh. “Mavzolei Bibi-Khanym.” Arkhitekturnoe nasledie Uzbekistana, edited by Galina Pugachenkova, 1960, pp. 60-74.

Acknowledgements

This essay reflects my ongoing research on the cultural and social history of Timurid architecture carried out within the project “Turks, Texts and Territory: Imperial Ideology and Cultural Production in Central Eurasia” funded by the Dutch Research Council (NWO).