How to cite

Abstract

Despite artistic engagement with photography in Iran almost immediately after the invention of the daguerreotype in 1839, the field of Islamic art history has had difficulty accepting the modern period and the medium of photography as part of its discipline. Studies on painted Iranian portraiture have often stopped before the introduction of photography, and only in more recent years has photographic portraiture and its influence on painting been examined. Due to this nascent state of the field, large gaps exist even on more traditional topics, such as the question of royal portraiture. This article presents the first examination of photographic royal portraiture and the visualization of kingship during the Iranian Constitutional Revolution (1905-1911). This topic, in comparison with earlier Iranian painted royal portraiture, has received considerably less attention. Photographic portraiture, together with printed and painted examples, from the reigns of the Qajar rulers Nasir al-Din Shah (r. 1848-1896), Muzaffar al-Din Shah (r. 1896-1907), Muhammad ʿAli Shah (r. 1907-1909), and Ahmad Shah (r. 1909-1925), will be analysed in connection with social and political developments in order to better understand the development of royal image making during a time of political turmoil.

Keywords

Portraiture, Qajar, Iran, Photography, Revolution, Constitutional Revolution, Kingship

This article was received on 18 July 2022 and published on 9 October 2023 as part of Manazir Journal vol. 5 (2023): “The Idea of the Just Ruler in Persianate Art and Material Culture” edited by Negar Habibi.

Introduction

Since the beginnings of the Qajar dynasty (1789-1925), royal portraiture communicated the ruler’s self-image to audiences near and far. Images of the ruler fulfilled different roles in the Qajar period: they represented or even stood in for an individual; they had ceremonial functions or were used in a display of allegiance; some connected an individual ruler to a larger dynasty, history, or culture; other paintings of rulers referenced historical or mythical figures, sometimes merging them with the figure of the ruler; they contributed to the legitimisation of the ruler by depicting them as divinely ordained or religiously legitimated; and some emphasized the gender of the ruler and the successful continuation of male lineage. Royal portraiture functioned as a representation of authority, often underlining political and military power, and many images depicted power by emphasizing material richness and grandeur.1 Such representations played an important part in the larger program of the ruler’s or the court’s image making, they came in a variety of sizes and media—not just “miniature” paintings in manuscripts—had varied audiences, and sometimes the portraiture functioned differently at home and abroad.2 Perhaps the most iconic royal depictions of the Qajar era date to the period of Fath ʿAli Shah (r. 1797-1834), whose life-size painted portraits emphasized his long, tapering beard and slim waist, and depicted the ruler adorned in jewels and armed with dagger and sword, were sent to foreign courts (Diba with Ekhtiar; Leoni; Rettig). During the reign of his grandson Muhammad Shah (r. 1834-1848), the recipients of these painted gifts reciprocated by sending a technological innovation to the Persian court that made a different type of portraiture possible: the daguerreotype camera (Schwerda, “Iranian Photography”; Tahmasbpour, “Photography”). The cameras sent by the British and the Russian courts were first operated by an ambitious Frenchman named Jules Richard (1816-1891), who photographed the young crown prince Nasir al-Din Mirza (r. 1848-1896) and his sister ʿIzzat al-Dawla (1834/5-1905) on the 15th of December 1844, in Tabriz. Sadly, the whereabouts of these daguerreotype portraits remain unknown (Adle with Zoka; Mahdavi).3 Fourteen years later, another Frenchman, Frances Carlhian (1818-1870), became Nasir al-Din’s personal photography instructor. Soon a darkroom with the suitable equipment for the newest photography technology, the wet collodion process, was set up for the king, the position of court photographer was established, and the subject of photography was introduced at Iran’s first polytechnical college, the Dar al-Funun (Ekhtiar, “Nasir al-Din Shah“; Ringer, 67-108; Gurney and Nabavi).

Patron, Collector, and Maker of Photographic Portraiture: Nasir al-Din Shah Qajar (r. 1848-1896)

Based on the existing published research, if one thinks of photographic royal portraiture in modern Iran, one is led directly to Nasir al-Din Shah (r. 1848-1896). The king’s own sustained interest in photography and the portraits he took of his family and surroundings (including a self-portrait with his wives) have deservedly received wide attention (Behdad, “Royal Portrait Photography”, Camera Orientalis; Pérez González and Sheikh, “From the Inner Sanctum”; Tahmasbpour, Naser-od-din; Masoumi Badakhs). He was also a favourite subject of foreign photographers temporarily residing in or visiting Iran, including the early salt print portraits by the European photographers Henri de Couliboeuf de Blocqueville (active 1858-1866) and Luigi Montabone (1828-87) (Bonetti figs. 2 and 11). On his travels outside Iran, Nasir al-Din Shah would seek out famous photographers, including Nadar, W. & D. Downey, A.J. Melhuish, Herbert Rose Barraud, Abdullah Frères, and Count Stanislaw Julian Ostorog (known as Walery), to repeatedly have his likeness taken (Chi 7-22).

An example of the shah’s interest in being portrayed is the photograph taken by the British photographer Herbert Rose Barraud (1845-1896) on the king’s third and final trip to Europe in 1889 (fig. 1). In this seated studio portrait, the ruler’s facial expression is regal and serious. Yet while the face mirrors intense concentration, the shah must have moved one of his hands just before the image was taken, demonstrating that even the best-planned photograph still includes an element of chance. Photographic cards based on earlier portraits of the shah, known as cartes-de-visite or cabinet cards, depending on the size, were exchanged or given away as souvenirs or tokens of friendship (Plunkett; McCauley). These photographic objects also became the currency of Victorian celebrity culture, eagerly collected by those who did not have the good fortune of personally knowing those depicted.

Nasir al-Din Shah actively supported Iranian and Iran-based photographers and commissioned portraits from ʿAbdullah Mirza Qajar (1850-1909) (Ẕuka 98-108; Afshar) and Antoin Sevruguin (1840s-1933) (Barjesteh van Waalwijk van Doorn and Vogelsang-Eastwood; Bohrer; Scheiwiller, “Relocating Sevruguin”; Sheikh, “Sevruguin va taṣvirsazi”; Vorderstrasse). Sevruguin’s striking portraits of the king, which depict him at the height of his power, received special academic and curatorial attention.4 One reason for this was their visual attractiveness, technical skill, and variety. In addition to more traditional portraiture, some of Sevruguin’s photographs provide a glimpse into what might be Nasir al-Din Shah’s day-to-day life, showing him during activities, e.g. on the hunt, with the barber, supervising the unpacking of boxes in his museum at the Gulistan Palace, etc.5 Another reason for the popularity of Sevruguin’s photographs in academic discourse was their availability: Sevruguin’s images, produced with the wet collodion process and printed on albumen paper, existed in multiple copies—unlike previous photographic portraits of the king which were made as only a single copy (daguerreotypes or salt prints)—and travelled the world. While these images were not affordable for the masses in Iran, copies of the photographs were purchased by or gifted to the Iranian elites as well as foreigners, who later donated or sold the Sevruguin photographs to Western institutions, including the National Museum of Asian Art in Washington D.C.6 The photographs were also sent abroad by the court, for example to the Ottoman Empire, and two albums of Sevruguin photographs are today preserved in the archives of the Yıldız Palace in Istanbul (shelf marks 11/1255 and 11/1256).

At the same time as Sevruguin’s portraits of Nasir al-Din Shah were taken, Iranian painters, such as Mirza Muhammad Ghaffari (1848-1941), known as Kamal al-Mulk, made use of photography in their work (Ashraf with Diba; Diba, “Muhammad Ghaffari”, “Qajar Photography”; Roxburgh). Layla Diba discusses how in Iran the appreciation of photography by painters differed from photography’s reception in the West and how photography functioned as a shortcut to realism: “The enthusiastic adoption of photography by Qajar artists and intellectuals as a means of equalling the achievements of European paintings stands in marked contrast to how photography was received by the painting establishment in Europe. In Europe, its influence was short-lived and pictorial realism was soon replaced by Impressionism, whereas in Iran ‘realism’ remained the standard to which all artists were held until the middle of the twentieth century.” (“Qajar Photography” 92) Additionally, printed portraits of the king and his entourage were also circulated through the first illustrated newspapers published in Iran (Sattari).

However, Nasir al-Din Shah’s likeness was not only circulated through print at home, he had also become a favourite of the illustrated press during his trips to Europe, and many more or less realistic depictions of his activities abroad were published (Motadel). With all this material available, it is unsurprising that the existing scholarship on the history of Iranian photography has until now prioritised the rich photographic holdings of this period. However, it is worth the time and effort to examine how portraiture changes and develops after the momentous period of Nasir al-Din Shah.

The Photographic Experiments of Muzaffar al-Din Shah (r. 1896-1907)

Having waited to be crowned king for nearly half a century, Muzaffar al-Din Mirza left Tabriz, the crown prince’s place of residence, for the capital Tehran in 1896 after his father had been assassinated.7 Muzaffar al-Din was infected with his father’s passion for photography early on.8 The city of Tabriz had been the perfect environment for any interest in visual technologies. It was here that the first daguerreotypes in Iran had been taken and that the printing press had been introduced to Iran. The multi-ethnic city in the north of Iran had also attracted a number of professional photographers, including Antoin Sevruguin and his brothers, who had established their first studio there. During his long years as crown prince Muzaffar al-Din had his portrait taken in different poses and places, with changing accessories and clothes. One portrait from around 1887 shows the crown prince in a leisurely outfit with checked trousers, standing in a relaxed manner in front of a painted backdrop depicting a piano in a photo studio in Tabriz (fig. 2). Photographs such as this one speak to the prince’s creativity, playfulness, and interest in experimentation, but also to a certain nonchalance or ease that his father sometimes lacked (Tahami and Jalali; Chi 24-33).9

Another example illustrating Muzaffar al-Din Shah’s long-standing passion for photography is the composite birthday portrait created at the very beginning of his reign (fig. 3). The collage consists of nine different portraits depicting Muzaffar al-Din as both crown prince and monarch. The inscription on the photographic composite portrait explains that the portraits "were taken during the celebrations of his happy and blessed birthdays." We have evidence for elaborate celebrations of the birthdays of Qajar rulers from the time of Fath ʿAli Shah onward, for whom his favourite daughter Zia al-Saltana (1799-1873) organized the festivities (Brookshaw). Nasir al-Din Shah introduced the modern tradition of photographically capturing royal birthdays and anniversaries of rule. The composite birthday portrait presented to Muzaffar al-Din Shah in 1897 paid attention to global photographic trends as re-photographed collages of single photographs had become extremely fashionable (Elliott 66-83).

The collage also demonstrated the shah’s close relationship with Mirza Ibrahim Khan Saniʿ al-Saltana (1874-1915), his court photographer in Tabriz and in Tehran, on whom he not only conferred the title ʿakkas-bashi ([chief] photographer) but in the same year, 1897, also offered the hand of his wife’s sister, Zivar al-Sultan Ṭalʿat al-Saltana (dates unknown), in marriage (Gaffary). The king’s photographer thus became literally part of the royal family. Mirza Ibrahim Khan (1874-1915) was the son of Mirza Ahmad Saniʿ al-Saltana (b. 1848), who had become Nasir al-Din Shah’s court photographer after having studied photography, engraving, and porcelain making in Europe for seven years (Gaffary). The fourteen-year-old Mirza Ibrahim accompanied his father to Europe, where he participated in his studies and, after his return to Iran, joined the court of the crown prince in Tabriz. He and Muzaffar al-Din had therefore known each other for many years when the latter became king. This familiarity, but also their mutual respect, is evident in the portraiture.10

In 1900, 1903, and 1905, Muzaffar al-Din Shah went on trips to Europe and took his photographer Mirza Ibrahim with him. Unlike his father’s trips, Muzaffar al-Din’s trips were built around long stays in spa towns like Contrexéville in France or Carlsbad in the Austrian-Hungarian Empire due to his poor health. Despite this, he had ample time to inform himself about the newest technological developments, including the introduction of the picture postcard and the discovery of early cinematography. The latter was described by the shah with interest in his travel diary (Qajar 146). This newly found interest resulted in Mirza Ibrahim training as a cameraman and film projector on their first European trip together, while also documenting the travels photographically (Gaffary). On the king’s second trip to Europe, Mirza Ibrahim again made sure to visually document the events and the two published travelogues of Muzaffar al-Din Shah (which are yet to be translated into English) were illustrated with these photographs (Qajar, Safarnama-ye Farangistan: Safar-i avval; Safarnama-ye Farangistan: Duvvumin safarnama).11 Mirza Ibrahim also found time to study new developments in printing on that trip and purchased the necessary equipment to establish his own printing company after his return to Iran. His interest in technological developments is also apparent in extraordinarily large-sized portraits, which he made of Muzaffar al-Din Shah. On one portrait, a beautifully calligraphed inscription tells us that the photograph was taken by Mirza Ibrahim to document the celebration of Nowruz in March 1898, and an additional, much smaller inscription, potentially in the hand of the photographer, states that he reprinted the image in the spring of 1901 after enlarging it fourteen times.12 Printing such a large image was technically sophisticated and it attests to the careful archiving and reusing of the photographs in the palace. Today over one thousand photo albums and more than forty thousand photographs are kept in the photographic archives of the Gulistan Palace, demonstrating both the Qajar passion for photography and the interest in keeping a record for future generations (Simsar; Tahami and Jalali; Nabipour and Sheikh).

![Enlarged by the court photographer Mirza Ibrahim Khan, <i>A Large-Sized Portrait of Muzaffar al-Din Shah Qajar</i>, dated 1323/1905, gelatin silver print (private collection). Inscribed: <i>Hasb al-amr-e mobarak-e a'la-hazrat-e homayuni ruhana fadahu dar 'akkas-khaneh-ye mobarakeh agrandisman shod gholam-e khanazad Ibrahim ibn sani' al-saltanah 1323</i>, 'By the order of the blessed, His Majesty [Muzaffar al-Din Shah], the monarch—may our soul be sacrificed for him—that was enlarged in the Royal Photography studio,' signed: 'The servant at court, Ibrahim ibn Sani' al-Saltanah, 1323 (1905-06)'.](https://bop.unibe.ch/manazir/article/download/8823/version/9109/13403/46421/avecijoqkrek.webp)

A second even larger portrait, with the dimensions 119 x 85 cm, confirms that Mirza Ibrahim successfully mastered the difficult technical skill necessary to enlarge photos, to which he refers in the portrait’s Persian inscription by using the French name for the process, agrandissement (fig. 4). The monumental portrait depicts a seated Muzaffar al-Din looking straight at the viewer, dressed in a western suit with a flower attached to his lapel and his arms resting on a cane. No diamonds are attached to his chest, nor does his lambskin hat bear embellishments. This life-size portrait might be similar to his progenitors’ portraits in size, yet it could not be more different. The king’s choice of clothing signifies the increased contact with Europe and the cane, which has filled the place usually taken by swords and daggers in his forefathers’ pictures, points to his failing health. In addition to the portraits taken of the king by his court photographers, a large number of commercial portraits in the shape of picture postcards had also come into circulation. These were mainly photographs taken by European photographers and depicting the king and his entourage during his trips to European spa towns.13 Whereas Nasir al-Din Shah’s likeness had been disseminated on the carte-de-visite, at the beginning of the twentieth century the postcard had begun to take the spotlight and was reaching larger audiences (Cure).

The stunning and somewhat melancholic portrait of Muzaffar al-Din Shah was taken at the end of 1905 (fig. 4), at the beginnings of a time of revolutionary turmoil. Less than a year later Muzaffar al-Din Shah would sign the constitution on his deathbed and usher in a new era.

Depicting the Rise and Fall of Muhammad ʿAli Shah (r. 1907-1909)

While a large number of photographic images exist of his grandfather Nasir al-Din Shah and his father Muzaffar al-Din Shah, there are comparatively few images taken of Muhammad ʿAli Shah (r. 1907-1909). The main reason for this might be his very short period of rule during a tumultuous period in Iran’s history. Similar to the absence of images of the founder of the Qajar dynasty, Aqa Muhammad Shah (r. 1789-1797), a lack of time and resources, and a lack of concrete power, hindered a concentrated form of image making during this later period. Due to this dearth of portraiture of Muhammad ʿAli Shah, most publications on royal Qajar portraiture focus on the rulers before him and spend little or no space covering his rule or that of his son Ahmad.14 Yet, despite the small number of images, it is worth examining how Muhammad ʿAli Shah engaged with portraiture during his short and intense rule in a politically turbulent period (Shablovskaja).

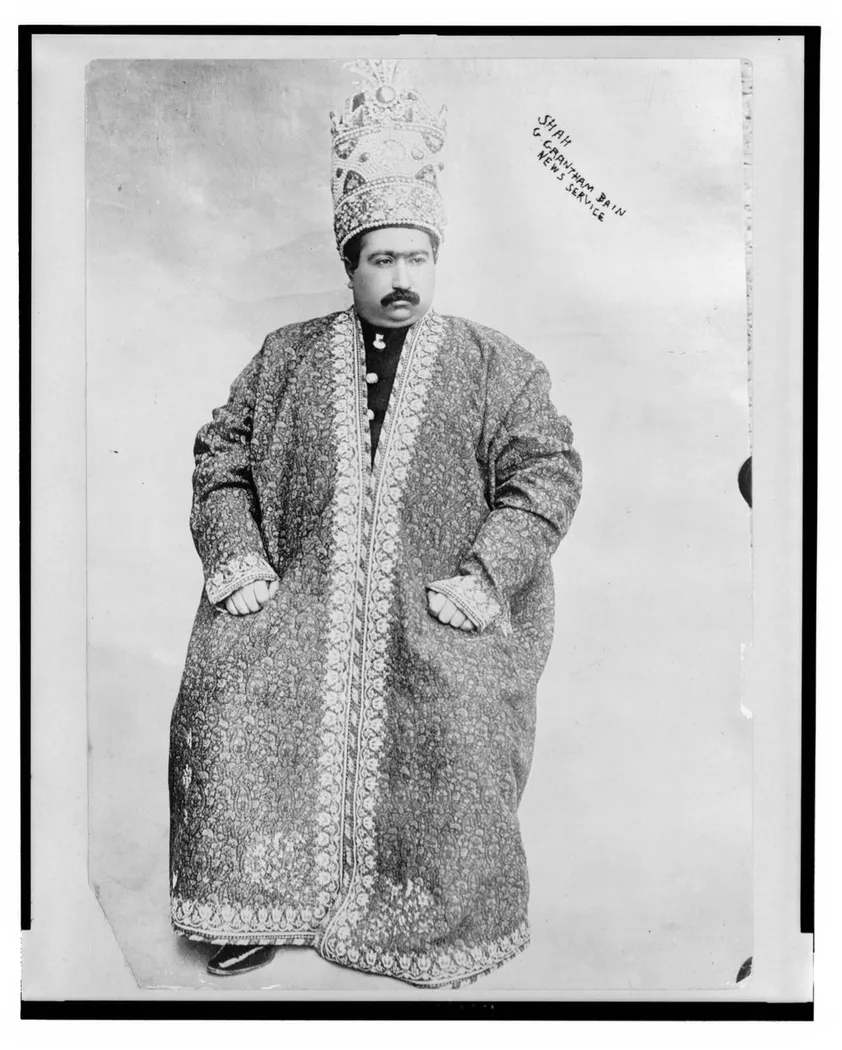

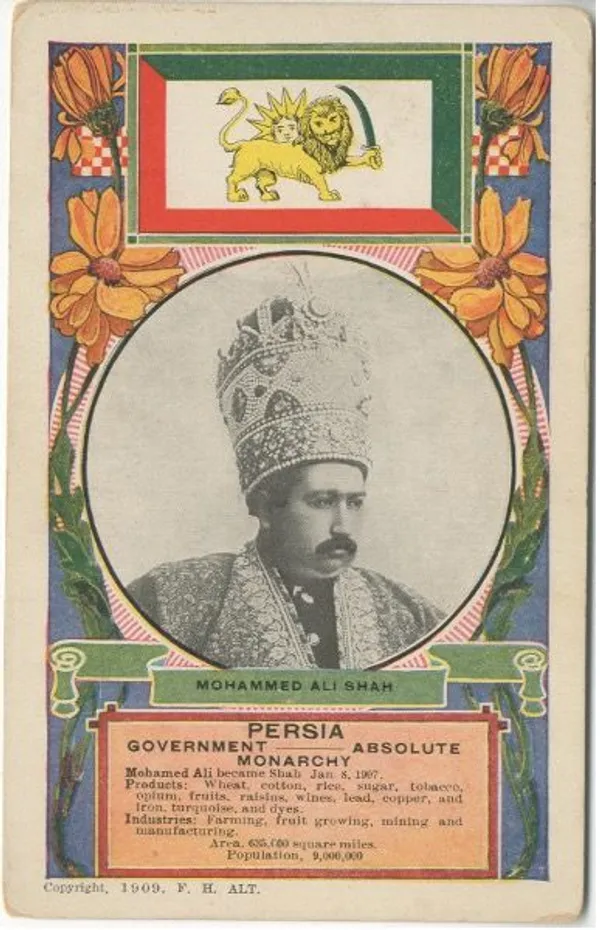

A small number of official photographic portraits taken of Muhammad ʿAli Shah after he had been crowned king exist. Interestingly, the small corpus of images heavily features images related to the shah’s coronation, which is a break with the image program of his three direct predecessors, who did not pay much attention to memorializing this event. One example for this is the photograph of a seated Muhammad ʿAli Shah, wearing a heavy crown, which was circulated by the Bains News Service (fig. 5). What this and the other formal photographs of Muhammad ʿAli Shah have in common is that they depict a serious looking monarch who appears to be burdened by the weight of the crown and other regalia and who unlike his predecessors does not seem to enjoy sitting in front of the lens.

Besides this lack of charm or playfulness, the interest in novelty or modernity that was apparent in Nasir al-Din Shah’s and Muzaffar al-Din Shah’s imagery is also absent here—with perhaps the exception of a velvet jacket emblazoned with Muhammad ʿAli Shah’s image and a painted portrait with a photographic background now at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which illustrate some interest in visual and artistic innovation—the formal photographic portraiture of Muhammad ʿAli Shah appears to be almost going backward in time aesthetically and technically.15 The photograph circulated by Bains in 1907 (fig. 5) is fully centered on the large, seated figure of the shah and emphasizes his power through what he is wearing; the royal robe (khilʿat) made from expensive gold brocade (zaribaf) and the tall, jewel-encrusted crown (Floor). The Kayanid crown, which features here, was the symbol of the Qajar dynasty and perhaps the best-known item of the Iranian crown jewels (Amanat). The crown originated from the time of the first Qajar ruler, Aqa Muhammad Shah, and was possibly made to his instructions. The golden dome of the crown was embellished with gemstones and pearls, likely captured from the Zand dynasty (1750-79). Aqa Muhammad Shah’s successor Fath ʿAli Shah later had a new version of the Kayanid crown made, reusing the same jewels, and keeping the illustrious name. The king frequently wore the crown on official occasions, and in Abbas Amanat’s words, “The dazzling king in his magnificent attire and regalia was a reminder to neighbouring powers, including the British, the Russians, and the French, of the political stability and continuity that had resumed in Iran.” (29) After Fath ʿAli Shah’s reign the crown was only worn at coronation and it nearly completely disappears from royal portraiture as Muhammad Shah, Nasir al-Din Shah, and Muzaffar al-Din Shah favoured comparatively less ostentatious markers of royalty such as the aigrette and bazubandha (armbands). In contrast, the portrait of Muhammad ʿAli Shah relies heavily on the symbolism of the crown and the robe to visualize royal authority and power. The emphasis on the Kayanid crown in the portraiture of Muhammad ʿAli also suggests the possibility of a conscious link to his powerful predecessor Fath ʿAli Shah. Furthermore, the focus on crown and robe underlines the connection between political power and material wealth at a time when the royal coffers were actually empty. A different photograph from this same series, taken in 1907 by an unidentified photographer, was used for a North American postcard two years later, in 1909, after Muhammad ʿAli Shah had tried to abort political reforms and reintroduce absolute monarchy (fig. 6). For the first time since the period of Fath ʿAli Shah, the Kayanid crown took centre stage in royal portraiture again. It is as if the new shah had to visually underline his right to the throne and wanted to connect his rule to a time where the introduction of a parliament was unheard of. In these two and several similar photographs, the focus on the oversized Kayanid crown appears to visualize royal authority and wealth while Muhammad ʿAli, through his wearing of the crown, seemingly paid homage to Qajar cultural tradition. Yet, in reality, little wealth and belief in family legacy remained, and so Muhammad ʿAli Shah soon pawned the imperial crown at a European bank in Tehran and, after his dethronement in 1909, took those crown jewels that he hadn’t pawned with him into exile (Bayat 107, fn. 32).

The first photograph of Muhammad ʿAli as Shah, printed in the London Illustrated News in January 1907, featured the by-line Walery, referring to the photographer Count Stanislaw Julian Ignacy Ostorog (1863-1935) (fig. 7). The photograph depicts Muhammad ʿAli Shah seated in uniform with his sword, three of his courtiers are behind him. The photograph lacks the elegance paired with authority of the first portrait of Nasir al-Din Shah, who is seen focused yet full of interest (fig. 1); the grandson and his entourage look as if being photographed is a duty, and one that makes them slightly uncomfortable.

This is also the case for several of the other official portraits of Muhammad ʿAli Shah. The other portraits appear to suggest that the shah neither had the time, resources, interest, nor the natural charm needed for successful royal image making.16 Indeed, he would have been hard-pressed to find a positive audience for such images as his rule faced widespread criticism in Iran and he was finally forced to abdicate in 1909. This dethronement was not only pursued by the Constitutionalists of Tehran and Tabriz. The religious authorities in Najaf also did not hold back about their disappointment in Muhammad ʿAli in a telegram sent to Tehran: “The deposition of Muhammed ʿAli Mirza, due to his great betrayal of religion, government, and nation, is obligatory by sharʿ [religious] and qanun [constitutional] law.” (Bayat 106).

Yet despite this relatively small investment in image making compared to his predecessors, Muhammad ʿAli Shah’s image was distributed around the globe during his brief reign, mainly through illustrated newspapers and postcards. In 1909, the Ottoman journal Resimli Kitap discussed the abdication of Muhammad ʿAli Shah and featured two photographs of him, one with his father and predecessor, and the other depicting him with his own son and successor (Resimli Kitap, June 1909, 895). In the following year, the same journal only featured representations of his predecessor Muzaffar al-Din and his successor Ahmad Shah as personifications of Iranian constitutionalism. The figure of Muhammad ʿAli Shah had already disappeared, an example of a strategic erasure, which would also be performed in Qajar portraiture (Resimli Kitap, June 1910, 820).

Another interesting example that demonstrates how far his image was circulated and which appears to foreshadow the brevity of his rule is from the Chinese weekly Dongfang Zazhi (The Eastern Miscellany) (fig. 8).17 The photograph introduces the then-newly crowned Iranian shah and visualizes the beginning of his rule by depicting Muhammad ʿAli in a similar uniform to that of the previous image, with the sword at his side. As the background has been removed and the image pasted in the middle, the new ruler appears somewhat forlorn. The caption informs us that this is "the current king of Persia, Mi-sa." (Bosi jin wang Misa).18

On the previous page of the journal, before the reader turns the page to see Muhammad ʿAli, another figure bears striking similarities to him: a moustachioed man dressed in a similar ceremonial uniform, holding a sword (fig. 8). This is This is King Kojong (r. 1864-1907; emperor from 1897), who believed that in order to become a modern nation-state Korea had to engage with Meiji Japan and the Western powers. Yet in late 1905, Japan took partial control of Korea and later replaced Emperor Kojong with his son Sunjong, a mere figurehead, in 1907 (Park 226). The replete visual similarities appear to almost foreshadow Muhammad ʿAli’s dethronement and replacement with his son, which was later reported, yet not illustrated, under the title “How Regretful the Dethroned Persian King Is (Ke’ai Boshi zhi Fei-huang)” (Wang, 371, footnote 6).

![Unidentified photographers, <i>Muhammad ‘Ali, the New Shah of Iran and Yi Hui, the Former Emperor of Korea</i>, reproduced in: <i>Dongfang zazhi</i>, no. 4, issue 6 (1907), 8-9. Accessible here: [<a href="https://archive.org/details/dongfangzazhi-1907.08.03/page/n8/mode/2up">https://archive.org/details/dongfangzazhi-1907.08.03/page/n8/mode/2up</a>]. ](https://bop.unibe.ch/manazir/article/download/8823/version/9109/13403/46443/w0n1djpul59w.webp)

Even though from an earlier period, the lines from this Muharram elegy appear to describe Muhammad ʿAli Shah’s situation well, especially his later failed return from exile:19

فارس افلاک را در قصد شاه کم سپاه

آه آه رزم جوی و کینه خواه

خود ز اکلیل و ثریا جوشن و مغفر نگر

در نگر کینه اختر نگر

The horseman of Heavens is after the King with his small army

woe he’s belligerent and vengeful

Even the Pleiades and Iklil wear armour and helmet, look

consider it look at the rancour of Heaven

As we shall see below the same elegy would later be appropriated in a very different context to refer to Muhammad ʿAli’s young son, the crown prince Ahmad Mirza, and it will provide us with a better understanding on how to understand his imagery.

Ahmad Shah (r. 1909-1925) , the Boy King as the Ideal of the Constitutionalist Ruler

After Muhammad ʿAli and his harem’s departure into exile in Odessa, his young son Ahmad was made ruler against his will. He was proclaimed shah in the presence of those who now shared political power in Iran: The Constitutionalist politicians and mujahidin, the ulama, the remaining Qajar grandees, and the foreign embassy officials. Azud al-Mulk Nayib al-Saltana, an elderly Qajar prince, was made regent (Bayat 106, fn. 31). On the images of the new ruler his tender age is directly apparent.20 An Iranian collaged postcard features a portrait of the young shah in the typical ceremonial uniform, which had been worn by his predecessors, with a sword almost too large for him and a cap embellished with an aigrette instead of the large, towering Kayanid crown (fig. 9). In direct contrast with his father, he is depicted as the ideal of a Constitutionalist ruler. Above the image of Ahmad Shah are two flags and an emblem adorned with the sword-wielding sun-lion symbolising the Qajar dynasty, directly underneath the flags are florally bordered rectangular fields, which are inscribed with “Souvenir of the Iranian Revolution, 1324-1327” (yadgar-i rivulusiyuun-i Iran 1324-1327) and “Long live the Constitutional Movement of Iran” (zindabad mashruṭa-yi Iran), visually and textually linking the Qajar dynasty to the new political reforms.

The young shah is surrounded by miniature portraits of some of his royal predecessors in the shape of stamps, with Muzaffar al-Din, under whose rule the constitution was introduced, taking pride of place. The young ruler’s image is captioned in French as “Constitutionalist king” (roi constitutionnel), followed by a benediction in Persian, which also describes Ahmad as a Constitutionalist monarch: “May God protect Sultan Ahmad Mirza, Padishah of the Constitutionalist Movement of all of the Iranian lands from any calamities” (aʿlahazrat-i humayuni Sultan Ahmad Mirza padishah-i mashruṭa-yi kul-i mamalik-i Iran saniha allah ʿan alhadathan). The postcard celebrates Ahmad Shah as a Constitutionalist monarch and links him as the ruler to the Constitutionalist movement, making them inseparable.

At the same time, this postcard as a celebration of political reform is also an example of the engagement with and participation in novel forms of communication and thought, including new vocabulary, concepts, such as mashruṭa and rivuluusiyun, and an emphasis on the importance of a faster, wider communication through the postal service, of which this postcard and the stamps it features is a part itself.21 As an example of collage, embracing new forms of art and visual culture, the postcard is more closely related to those images circulated by Muzaffar al-Din Shah than to those by Ahmad Shah’s direct predecessor, Muhammad ʿAli. While this postcard was in circulation, Ahmad Shah was also celebrated as a Constitutionalist monarch in new verse. The earlier Qajar elegy, previously quoted, had been fully transformed:22

ای شهنشاه جوان شیران جنگ آور نگر در نگر عالمی دیگر نگر

ملتی را راحت از مشروطه سر تا سر نگر در نگر عالمی دیگر نگر

پادشاهی کن که دوران جهان بر کام تست رام تست شاه احمد نام تست

در محامد خویش را همنام پیغمبر نگر در نگر عالمی دیگر نگر

Oh young King of Kings, look at the belligerent lions

consider it look at a different world

Look at a nation, completely at ease by virtue of the constitution

consider it look at a different world

Rule, the course of the world complies to your wish

submits to you King Ahmad is your name

In praiseworthiness, regard yourself the prophet’s namesake

consider it look at a different world

(Haag-Higuchi, 61)

As Roxane Haag-Higuchi writes, “This early Qajar elegy was transformed into a triumphal song about the end of the period of lesser despotism (istibdād-i saghīr) and the enthronement of Aḥmad Shāh in 1909, published in Nasīm-i shumāl on 1 August 1909. The change of mood is obvious in the refrain which transforms the fatalistic ‘consider it, look at the rancour of the stars’ into the optimistic, future-oriented ‘consider it, look at a different world’.” (61). Haag-Higuchi’s explanation may guide us in understanding why images of a young and shy-looking Ahmad Shah were so popular—there appear to be fewer images of him at a more mature age—as his young age was linked to a new beginning and to a youthful optimism for the changing world.

At the same time, Ahmad Shah’s young age and the introduction of a regent for him also emphasized his lack of experience and concrete power; a vacuum that was filled by the parliament and the Constitutionalist ministers. While the previous postcard closely linked Ahmad Shah to the Constitutionalist Movement (mashruṭa) primarily through captions, benedictions, and the title padishah-i mashruṭa-yi Iran or roi constitutionnel, a different strategy of political symbolism is followed by a contemporary oil painting of Ahmad Shah (fig. 10).23

The painting by Assad-Allah al-Husayni Naqqash-bashi, whose work was likely aided or influenced by photographs, also depicts Ahmad Shah as a Constitutionalist monarch. However, in the portrait the artist visualized and defined this new kind of kingship by emphasizing the sharing of power with not only the parliament but also a much more powerful cabinet of ministers. Many earlier painted and photographic royal portraits had solely focused on the king or, if introducing an entourage, still visualized the king’s special position and emphasized his power (e.g. Fath ʿAli Shah’s ceremonial saf-i salam [greeting queue] portraits) (Diba, “Images of Power” 36-9; Diba, “From the Miniature”).

In this painting of Ahmad Shah and his cabinet, the king, while still at the centre, has become one amongst a group. The men that surround him and the crown prince to the left share his space, and unlike in the earlier ceremonial group portraits from Fath ʿAli Shah’s reign, Ahmad Shah is not provided with an additional elevation or other manners of spatial separation. The painting draws on traditional markers of power and kingship by depicting the men’s robes of honour or ceremonial uniforms, their jewel-encrusted medals, the black fur caps emblazoned with the sun-lion or the royal aigrette, while adding new elements, such as the physical closeness of the cabinet to the king, the older men’s taller size as compared to the ruler, and the listing of all of the men’s names. Some of the medals contain miniature portraits, which again give Muzaffar al-Din Shah, the first Constitutionalist king, an elevated position, while purposefully excluding his successor, the tyrant Muhammad ʿAli Shah – a novel measure of erasure or ‘cancellation’ that had not taken place in Qajar portraiture before. The group portrait (fig. 10) and the postcard (fig. 9) also symbolised links to the West and to modernity by being painted in oil or printed in the form of a collage as a collotype, and visualised new ideas and concepts, which had been introduced to Iran, thereby commenting on political and social change that took place during the early twentieth century.

Conclusion

Lens-based royal portraiture produced in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century in Iran provides a fascinating insight into a period of intertwined social, political, technological, and artistic change. In this article I have demonstrated how the political exigencies of the day, paired with the personality of different rulers, affected both the style and technology of the imagery. Yet, at the same time, aesthetic trends and technological developments also influenced royal image making, or, as in the case of Muhammad ʿAli Shah, were consciously rejected.

The large body of photographic royal portraiture demonstrates that photography was embraced by late Qajar rulers. Both Nasir al-Din Shah and Muzaffar al-Din Shah were intrigued by the technology and had close relationships with their photographers, and in the case of Nasir al-Din Shah even took photographs themselves. The myriad photographic portraits of Nasir al-Din Shah taken in Iran and abroad provide us with information about how the shah wanted to be seen and demonstrate his interest in the nuances of staging and posing for portraiture as well as in photography and printing culture’s technological advancements.

The illustrated European press was fascinated with the lives of the Persian shahs and we know that Nasir al-Din Shah had European newspapers and travelogues read to him, and followed how he was depicted abroad. The artists of the French illustrated journal L’Illustration devoted three issues to the Shah’s trip to Paris in 1873 and, with artistic liberty, drew how they imagined him in both the bath and the bedroom, demonstrating the French audience’s interest in the everyday life of the monarch.24 As mentioned earlier, similar quotidian scenes, which are quite unusual for royal portraiture, were later photographically documented by Sevruguin; what prompted these photos or even if the images were meant to circulate beyond the palace is still unknown. Perhaps they were even inspired by the detailed, yet mostly fantastical reporting of the most mundane details of the shah’s travels in the French and English illustrated press. During the reign of Nasir al-Din Shah’s son, Muzaffar al-Din Shah, it had become easier and faster to reproduce photographic images, as demonstrated by the many postcards depicting the ruler on his travels, and so a control of image circulation became even less possible.

It is recorded that Fath ʿAli Shah contributed to the making of his own image by posing for paintings and directing the artist (Ekhtiar, “From Workshop and Bazaar” 52). While we know that Nasir al-Din Shah and Muzaffar al-Din Shah commissioned their own photographic likenesses, and hired and communicated with photographers— in the case of the former also had the skill both to draw and take photographic images himself—we know less about their concrete involvement in the making of official portraiture. Furthermore, we have even less information for the last two Qajar rulers, Muhammad ʿAli Shah and Ahmad Shah. Relevant accounts by photographers of this period have also not yet come to light. This is unfortunate as they would provide insight into the artist’s perspective and might change our understanding of specific developments. However, we do know that the painter Kamal al-Mulk, who had been crucial for the development of modern painting in Iran and had painted many likenesses of Nasir al-Din Shah, refused to paint Muhammad ʿAli Shah’s portrait because the artist was committed to supporting the Constitutional Revolution.25 Other artists might have shared his belief, which may contribute to explaining the small number of portraits of Muhammad ʿAli Shah. While this examination has demonstrated that the rulers engaged with the arts (specifically the camera) in different ways and that the visual definition of kingship and power was modified according to the current shah, many open questions remain: How much did the rulers of the late Qajar period engage with painters and photographers, did they participate in directing their image? Was this also the case for the young Ahmad Shah, for example? How far was this kind of image-making centrally orchestrated? Perhaps, more research will reveal a much more diverse corpus of images, thereby suggesting less royal influence on image making in the late Qajar period. One avenue to research this question further will be the engagement with written primary sources, e.g. diaries, letters, and travelogues written by the rulers, the courtiers, and the artists. Another further avenue will be to investigate caricatures and other critical imagery, which circulated at the same time as the royal imagery.

Regrettably, the period from Muzaffar al-Din Shah to the end of the Qajar era has, so far, received little attention from historians of art or visual culture despite the existence of ample source material. In the past, this neglect of Qajar art as compared to earlier Iranian art was often based on the problematic idea of decline and the inaccurate belief that the Timurid and Safavid dynasties were allegedly being further removed from foreign and modern influences and thus as examples of a “more purely Islamic or Persian art” more worthy of study (Gruber). During the last few years this has finally changed as the number of exhibitions and books on Qajar art have demonstrated (Schwerda, “The Prince and the Shah”). It is to be hoped that both the arts of the Qajar court during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century and the arts and popular culture outside of the court at this time, including the history of photography, will continue to receive more attention. As this essay has demonstrated, many fascinating questions remain open.

Bibliography

Adle, C. with Y. Zoka. “Notes et documents sur la photographie iranienne et son histoire : I. les premiers daguerreotypistes c. 1844-1854/1260-1270.” Studia Iranica, vol. 12, no. 2, 1983, pp. 249-80.

Afshar, Iraj. “Some Remarks on the Early History of Photography in Iran.” Qajar Iran: Political, Social, and Cultural Change, 1800-1925, edited by Edward Bosworth and Carole Hillenbrand. Edinburgh UP, 1983, 261-290.

Amanat, Abbas. “The Kayanid Crown and Qajar Reclaiming of Royal Authority.” Iranian Studies, vol. 34, no. 1-4, 2001, pp. 17-30.

Ashraf, A. with Layla Diba. “Kamāl-al-Molk, Mohammad Ḡaffāri.” Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition, https://iranicaonline.org/articles/kamal-al-molk-mohammad-gaffari. Accessed on 19 May 2022.

Barjesteh van Waalwijk van Doorn, Ferydoun and Gillian M. Vogelsang-Eastwood, editors. Sevruguin’s Iran: Late Nineteenth Century Photographs of Iran from the National Museum of Ethnology in Leiden, the Netherlands. Zaman and Barjesteh vanb Waalwijk van Doorn, 1999.

Bayat, Mangol. Iran’s Experiment with Parliamentary Governance: The Second Majles, 1909-1911. Syracuse UP, 2020.

Behdad, Ali. Camera Orientalis: Reflections on Photography of the Middle East. The University of Chicago Press, 2016.

---. “Royal Portrait Photography in Iran: Constructions of Masculinity, Representations of Power”. Ars Orientalis, vol. 43, 2013, pp. 32-46.

Bohrer, Frederick N., editor. Sevruguin and the Persian Image: Photographs of Iran, 1870-1930. University of Washington Press, 1999.

Bonetti, Maria Francesca and Alberto Prandi. “Italian Photographers in Iran 1848-64,” History of Photography, vol. 37, no.1, 2013, pp. 14-31.

Brookshaw, Dominic Parviz. “Zia’ al-Saltanah.” Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition, https://iranicaonline.org/articles/zia-al-saltana. Accessed on 17 Jul. 2022.

Chi, Jennifer Y., editor. The Eye of the Shah: Qajar Court Photography and the Persian Past. Institute for the Study of the Ancient World, New York UP, Princeton UP, 2016.

Cure, Monica. Picturing the Postcard: A New Media Crisis at the Turn of the Century. University of Minnesota Press, 2018.

Diba, Layla S. with Maryam Ekhtiar, editors. Royal Persian Paintings: The Qajar Epoch, 1783-1925. I.B. Tauris in association with the Brooklyn Museum of Art, 1998. Catalog of the eponymous exhibition, 23 Oct. 1998 – 24 Jan. 1999, Brooklyn Museum of Art, Brooklyn.

Diba, Layla S. “From the Miniature to the Monumental: The Negarestan Museum Painting of the Sons of Fath Ali Shah,” Khamseen: Islamic Art History Online, published 28 Oct. 2020, https://sites.lsa.umich.edu/khamseen/topics-presentations/2020/from-the-miniature-to-the-monumental-the-negarestan-museum-painting-of-the-sons-of-fath-ali-shah/. Accessed 30 Aug. 2023.

---. “Images of Power and the Power of Images: Intention and Response in Early Qajar Painting (1785-1834).” Royal Persian Paintings: The Qajar Epoch, 1783-1925, edited by Layla S. Diba with Maryam Ekhtiar. I.B. Tauris in association with the Brooklyn Museum of Art, 1998. Catalog of the eponymous exhibition, 23 Oct. 1998 – 24 Jan. 1999, Brooklyn Museum of Art, Brooklyn, pp. 30-49.

--- “Muhammad Ghaffari: The Persian Painter of Modern Life”. Iranian Studies, vol. 45, no. 5, Sept. 2012, pp. 645-659.

---. “Qajar Photography and its Relationship to Iranian Art: A Reassessment,” History of Photography, vol. 37, no. 1, 2013, pp. 85-98.

Ekhtiar, Maryam. “From Workshop and Bazaar to Academy: Art Training and Production in Qajar Iran.” Royal Persian Paintings: The Qajar Epoch, 1783-1925, edited by Layla S. Diba with Maryam Ekhtiar. I.B. Tauris in association with the Brooklyn Museum of Art, 1998. Catalog of the eponymous exhibition, 23 Oct. 1998 – 24 Jan. 1999, Brooklyn Museum of Art, Brooklyn, pp. 50-65.

---. “Nasir al-Din Shah and the Dar al-Funun: The Evolution of an Institution,” Iranian Studies, vol. 34, no. 1-4, 2001, pp. 153-163.

Elliott, Patrick, editor. Cut and Paste: 400 Years of Collage. National Galleries of Scotland, 2019. Catalog of the eponymous exhibition, 29 Jun. – 27 Oct. 2019, National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh

Fellinger, Gwenaëlle with Carol Guillaume, editors. L’Empire des roses. Chefs-d’oeuvre de l’art person du XIXe siècle. Snoeck and Louvre Lens, 2018. Catalog of the eponymous exhibition, 28 Mar. – 23 Jul. 2018, Louvre Lens, Lens.

Floor, Willem. “Kelʻat,” Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition, https://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/kelat-gifts. Accessed 14 Jul. 2022.

Gaffary, F. “Akkās-Bāšī,” Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition, https://iranicaonline.org/articles/akkas-basi-ebrahim. Accessed 17 Jul. 2022.

Gruber, Christiane. “Questioning the ‘classical’ in Persian painting: models and problems of definition.” Journal of Art Historiography, vol. 6, 2012, pp. 1-25.

Gurney, John and Negin Nabavi, “Dār al-Fonūn,” Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition, https://iranicaonline.org/articles/dar-al-fonun-lit. Accessed on 19 May 2022.

Haag-Higuchi, Roxane. “Muharram Elegies as Precursors of Revolutionary Poetry.” At the Gate of Modernism: Qajar Iran in the Nineteenth Century, edited by Éva M. Jeremiás. The Avicenna Institute of Middle Eastern Studies, 2012, pp. 55-64.

Helbig, Elahe. “From Narrating History to Constructing Memory: The Role of Photography in the Iranian Constitutional Revolution,” Iran’s Constitutional Revolution of 1906: Narratives of the Enlightenment, edited by Ali M. Ansari, Gingko Library, 2016, pp. 48-75.

Hellot-Bellier, Florence. “Joseph Désiré Tholozan (1820-1897): The passion of a ‘man of science’ for medicine and for Persia.” Putting the Shah in the Landscape, edited by Reza Sheikh and Corien Vuurman, International Qajar Studies Association, 2019, pp. 24-63.

Leoni, Francesca. “‘Taille de guêpe et barbe fleurant l’ambroisie’: Les portraits de Fath ‘Ali Shah.” L’Empire des roses. Chefs-d’oeuvre de l’art person du XIXe siècle, edited by Gwenaëlle Fellinger with Carol Guillaume. Snoeck and Louvre Lens, 2018. Catalog of the eponymous exhibition, 28 Mar. – 23 Jul. 2018, Louvre Lens, Lens, pp. 114-117.

Mahdavi, Shireen. “Rishār Khan,” Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition, http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/rishar-khan. Accessed on 19 May 2022.

McCauley, Elizabeth Anne. A.A.E. Disdéri and the carte de visite portrait photograph. Yale UP, 1985.

Masoumi Badakhs, Nasrin. “Nasir al-Din Shah Qajar: Az avalin-i selfie bazha-yi Iran.” ‘Aks, vol. 325, 2015, pp. 70-71.

Motadel, David. “Qajar Shahs in Imperial Germany.” Past & Present, vol. 213, 2011, pp. 191-235.

Nabipour, Alireza and Reza Sheikh. “The Photograph Albums of the Royal Golestan Palace: A Window into the Social History of Iran during the Qajar Era.” The Indigenous Lens? Early Photography in the Near and Middle East, edited by Markus Ritter and Staci G. Scheiwiller, De Gruyter, 2018, pp. 291-324.

Park, Eugene Y. Korea: A History. Stanford UP, 2022.

Pérez González, Carmen. “Written Images: Poems on Early Iranian Portrait Studio Photography (1864-1930) and Constitutional Revolution Postcards (1905-1911).” The Indigenous Lens? Early Photography in the Near and Middle East, edited by Markus Ritter and Staci G. Scheiwiller, De Gruyter, 2018, pp. 193-220.

---. Local Portraiture: Through the Lens of the 19th Century Iranian Photographers. Leiden UP, 2012.

Pérez González, Carmen and Reza Sheikh, “From the Inner Sanctum: Men Who Were Trusted by the Kings.” The Eye of the Shah: Qajar Court Photography and the Persian Past, edited by Jennifer Y. Chi. Institute for the Study of the Ancient World and Princeton UP, 2016, pp. 132-157.

Plunkett, John. “Carte-de-visite.” Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography, edited by John Hannavy. Taylor & Francis, 2008, pp. 276-277.

Qajar, Muẓaffar al-Din Shah. Safarnama-ye Farangistan : safar-i avval. 1319/1901,

RP Sharq, 1363/1984.

---. Duvvumiin safarnama-ye Muẓaffar al-Din Shah be Farang be taḥrir-i Fakhr al-Mulk; ʿaks ha az Ibrahim Khan ʿAkkasbashi. RP Kavish, 1362/1983.

Rettig, Simon. “Illustrating Firdawsi’s Book of Kings in the Early Qajar Era: The Case of the Ezzat-Malek Soudavar Shahnama.” Revealing the Unseen: New Perspectives on Qajar Art, edited by Gwenaëlle Fellinger with Melanie Gibson. Gingko and Louvre éditions, 2021, pp. 42-55.

Ringer, Monica M. Education, Religion, and the Discourse of Cultural Reform in Qajar Iran. Mazda Publishers, 2001.

Roxburgh, David J. “Painting after Photography in 19th-Century Iran.” Technologies of the Image: Art in 19th-Century Iran, edited by David J. Roxburgh and Mary McWilliams Harvard Art Museums and Yale UP, 2017, pp. 107-130.

Sattari, Mohammad and Houshang Salamat. “Photography and the Illustrated Journals Sharaf and Sharāfat.” History of Photography, vol. 37, no. 1, 2013, pp. 74-84.

Scheiwiller, Staci Gem. Liminalities of Gender and Sexuality in Nineteenth-Century Iranian Photography: Desirous Bodies. Routledge, 2017.

---. “Relocating Sevruguin: Contextualizing the Political Climate of the Iranian Photographer Antoin Sevruguin (c. 1851-1933).” The Indigenous Lens? Early Photography in the Near and Middle East, edited by Markus Ritter and Staci G. Scheiwiller, De Gruyter, 2018, pp. 145-172.

Schwerda, Mira Xenia. “Death on Display: Mirza Riza Kirmani, Prison Portraiture and the Depiction of Public Executions in Qajar Iran”. Middle East Journal of Culture and Communication, vol. 8, 2015, pp. 172-191.

---. “How Photography Changed Politics: The Case of the Iranian Constitutional Revolution (1905-1911).” 2020. PhD thesis, Harvard University

---. “Iranian Photography: From the Court, to the Studio, to the Street.” Technologies of the Image: Art in 19th-Century Iran, edited by David J. Roxburgh and Mary McWilliams. Harvard Art Museums and Yale UP, 2017, pp. 81-106.

---. “Royal Portraiture in the Modern Age: The Photographic Portraits of Nasir al-Din and Muzaffar al-Din Shah Qajar”. Bonhams, The Lion and Sun: Art from Qajar Persia, 66, April 30, 2019, [bonhams.com/auctions/25434/lot/113/].

---. “The Prince and the Shah: Royal Portraits from Qajar Iran (exhibition review)”. International Journal of Islamic Architecture. vol. 8, no. 1, 2019, pp. 222–226.

Shablovskaia, Alisa. “Treacherous friends or disenchanted masters? Russian diplomacy and Muhammad ‘Ali (Shah) Qajar, 1911-1912.” British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies, vol. 4, 2021, pp. 611-628.

Sheikh, Reza. “National Identity and Photographs of the Constitutional Revolution.” Iran’s Constitutional Revolution: Popular Politics, Cultural Transformations and Transnational Connections, edited by Houchang Chehabi and Vanessa Martin. I. B. Tauris, 2010, pp. 249-276.

---. “Sevruguin va taṣvirsazi az Iran dar avakhar-e qarn-i nuzdahum va avvael qarn-e bistum-i milada.” ʿAksnāma, vol. 7, 1387sh/1999, pp. 2-13.

Simsar, Muhammad Ḥasan and Faṭimah Sirayan, editors. Kakh-e Gulistan (album khenah) : fehrist-e aksha-ye barguzidah-e ʿaṣr-e Qajar. Kitab-e Aban: Zariran ba hamkara-e Sazman-e Miras-e Farhangi va Gardishgari va Kakh-e Golistan, 1390/2011 or 2012.

Tahami, Ghulam Reza and Bahman Jalali, editors. Ganj-e payda: majmuʿeha-yi az ʿaksha-ye album khanah-ye Muze-ye Golistan hamrah ba resalah-ye ʿaksiye-ye ḥashriyah, neveshte-ye Muḥammad ibn ʿAli Mashkut al-Mulk. Daftar-e Pazhuhesh ha-ye Farhangi, 1377/1998.

Tahmasbpour, Mohammadreza. “Photography During the Qajar Era, 1842-1925.” Translated by Reza Sheikh. The Indigenous Lens? Early Photography in the Near and Middle East, edited by Markus Ritter and Staci G. Scheiwiller, De Gruyter, 2018, pp. 57-78.

---. Naser-od-din, Shah-e ʿakkas : piramun-e tarikh-e ʿakkasi-e Iran (Nâser-od-din, the Photographer King). Tarikh-i Iran, 2002.

Vorderstrasse, Tasha, editor. Antoin Sevruguin: Past and Present. The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, 2020.

Wang, Yidan. “The Iranian Constitutionalist Revolution as Reported in the Chinese Press.” Iran’s Constitutional Revolution: Popular Politics, Cultural Transformations and Transnational Connections, edited by Houchang Chehabi and Vanessa Martin. I. B. Tauris, 2010, pp. 369-380.

Zuka, Yahya. Tarikh-e ʿakkasi va ʿakkasan-e pishgam dar Iran. Sherkat-e Entesharat-e ʿElmi va Farhangi, 1997.

Acknowledgements

This article is dedicated to Elmar Seibel and Houchang Chehabi, whom I would like to thank for their kindness, friendship, and support throughout the years. I would also like to express my gratitude to Negar Habibi, who worked tirelessly on this special issue, as well as to the two anonymous reviewers, Fuchsia Hart, and Belle Cheves for their helpful comments on the article draft. I am grateful to Kenneth X. Robbins, Nick McBurney, Sam Cotterell, Nima Sagharchi, and Massumeh Farhad for their help with images and image permissions. The research for this article was supported via a Fellowship at the Institute for Advanced Studies in the Humanities at the University of Edinburgh. A part of this article was previously published by the same author under the title “Royal Portraiture in the Modern Age: The Photographic Portraits of Nasir al-Din Shah and Muzaffar al-Din Shah Qajar” in the printed and digital catalog accompanying the auction The Lion and the Sun, Art from Qajar Persia, at Bonhams, London, 30 April 2019.