How to cite

Abstract

The concept of “Just Rule” historically served to shape a king’s image and bolster the monarchy’s structure, often emulated by courtiers seeking to be part of the inner circle and perpetuating the idea of a Just Ruler. Influenced by the king’s interests, figures like Nasir al-Din Shah Qajar (r. 1848-1896) fostered monarchic strength through praises and art, particularly in the Nasiri era.

These illustrations, blending literature and visual art, became sought-after for adorning manuscripts and enhancing printed books during this period. This study examines Nasir al-Din Shah's portrayal in the One Thousand and One Nights manuscript (1852-1859), overseen by Abul-Hassan Ghaffari, Saniʿ al-Mulk (d. 1865). Characters resembling Nasir al-Din Shah appear throughout the manuscript. The study aims to analyze these images in relation to the manuscript’s content and their role in the discourse on portrait illustrations. Additionally, it explores how the idea of Just Rule was perpetuated by the patrons and artists involved in creating this manuscript.

Keywords

Qajar Art, Persian Court, Illustrated Manuscript, One Thousand and One Nights, Nasir al-Din Shah Qajar

This article was received on 25 July 2022 and published on 9 October 2023 as part of Manazir Journal Vol. 5 (2023): “The Idea of the Just Ruler in Persianate Art and Material Culture” edited by Negar Habibi.

Introduction

Nasir al-Din Shah Qajar (r. 1848-1896), the fourth king of the Qajar dynasty, ascended to the throne when he was eighteen. He was three years old when his father, Muhammad Shah (r. 1797-1834), succeeded Fath ʿAli Shah (r. 1834-1847). As the oldest son of Muhammad Shah, Nasir al-Din Mirza was appointed as the crown prince in 1835, and until his coronation, he was under the tutelage of his uncle, Bahman Mirza (1810-1883), in Tabriz (Bamdad 246).

After his father’s death in 1848, Nasir al-Din Mirza and his tutor and spiritual mentor, Mirza Taqi Khan Farahani (Amir Kabir) (1807-1852), travelled to Tehran, where he was crowned as Nasir al-Din Shah on Saturday night (the 22nd of the same month). Before arriving in Tehran, he appointed Mirza Taghi Khan as Sadr-i ʿAzam (the prime minister), giving him the title Atabak. Nasir al-Din Shah, who had several literary and artistic interests, was assassinated by Mirza Riza Kirmani in the Shah ʿAbdul-ʿAzim Shrine on 30 April 1896. Henceforth, the era of Qajar cultural glory began to wane.

The young Nasir al-Din Mirza studied literature, culture, and arts under the tutelage of great scholars in the Qajar period during his fifteen years stay in Tabriz where he studied science and the Turkish language. It is there he also became familiar with some Persian literature. During this period, Nizam al-ʿUlama was his tutor in Tabriz.1

As a Qajar prince interested in literature and arts, Nasir al-Din Mirza’s uncle, Bahman Mirza, and his great library in the Arg (Citadel) of Tabriz played an influential role in shaping the mentality of Nasir al-Din Mirza during his childhood. Appointed as Vicegerent of Azerbaijan (1839-1847), Bahman Mirza was a learned Qajar prince whose name, recommendation and support can be seen in his writing and translation of many exquisite books. He is known as the author of Tazkera al-Shuʿara-i Muhammad Shahi (Biography of Poets of the Reign Muhammad Shah) dated 1834 (Bamdad 196).

One Thousand and One Nights is considered one of the most important books translated and prepared by order of Bahman Mirza. The book is the Persian translation of the Arabic Alf Laylah wa Laylah, which is known in English as The Arabian Nights. The book consists of an initial story as well as a series of interrelated and embedded tales that are told by Queen Shahrazad to the king whose narration supposedly continues for one thousand and one nights.

Researchers have acknowledged the Iranian origin of the book, tracing its early version back to Persian literature. Early indications of these origins can be found in the works of two Arab historians: Meadows of Gold and Mines of Gems by Al-Masudi (896–957) and Al-Fihrist by Ibn al-Nadim (d. 995); having added some tales to the book, the Arabic authors and narrators finally titled the book as Alf Laylah wa Laylah (Atabay). During the Qajar era, however, Bahman Mirza commissioned a Persian translation of the book. ʿAbdul-Latif Tasouji (1880) translated the work from the Egyptian Bulaq edition (published in 1835),2 and Mirza Muhammad ʿAli Isfahani, known as Shams-ul-Shuʿara (the Sun of Poets), with the pen-name Soroush, composed some of the poems and added verses of other poets in the freshly translated text (One Thousand and One Nights 1–2).3 Prepared in 1844-1845, the translation was lithographically published in two volumes on 25 October 1845 in Tabriz.4

The young Nasir al-Din Mirza probably had access to the book, hence its possible important role in his education. Following the royal tradition when he accessed the throne, Nasir al-Din Shah established a royal bookbinding workshop and ordered an illustrated copy of One Thousand and One Nights. Abu Al-Hassan Ghaffari (d. 1865), and his thirty-four apprentices prepared this unparalleled and exquisite version under the management of Hussein ʿAli Khan Muʿayyir al-Mamalik (1798-1857) in Majmaʿ al-Sanayaʿ Nasiri (Nasiri Center of Art and Craftsmanship) (Yousefifar 42-64).5

Ordering an illustrated version of a fictional tale, such as One Thousand and One Nights in the royal workshop is an interesting case when compared with previous kingly commands which were primarily concerned with the illustrated exquisite copies of the historical, epic, and heroic stories of Ferdowsi’s Shahnama (Book of Kings) or Nizami’s Khamsa (Quintet). More importantly, this copy remains the only manuscript from the Nasiri Court, the only illustrated manuscript of the Persian translation of the Arabic Alf Laylah wa Laylah and the only Persian manuscript with 3655 illustrations distributed in 1136 double folios.6 Additionally, it is considered the last illustrated manuscript produced at the Iranian royal court.

The exorbitant cost of the book indicates the significance of this version for the young king; 6850 Tomans, the equivalent to one-sixth of the total cost for the construction, decorations and furnishing of the multi-story Shams al-ʿImara mansion in Arg-i Shahi (Royal Citadel, today in Gulistan Palace), were spent to make this copy. A newly-found document also refers to the final cost as being more than the initial amount set in the contract (Bakhtiar 130-132; Boozari and Shafiei 233-251). The young king’s interest in this book was known to the courtiers and influential people, who, in turn, used the illustrated or printed copies as a basis to converse with the young king, mostly to adulate and venerate the monarchical status and garner the king’s attention as well as, perhaps, to a lesser extent, give the young king admonitions concerning ethics and statecraft.7

To communicate reformist or sycophantic messages, the illustrators or patrons replaced the fictional kings with the portraits of Nasir al-Din Shah—supposedly to ascribe positive traits of the fictional kings to him. Among the 3655 illustrations in the manuscript of One Thousand and One Nights, 32 illustrations contain Nasir al-Din Shah’s portrait. The present study focuses on the 19 illustrations that reinforce monarchical status and adulate the king’s rank. The other thirteen illustrations that are not studied here focused on a more didactic and reformist approach.

Nasir al-Din Shah’s Portrait in the Illustrations of the Manuscript of One Thousand and One Nights

Nasir al-Din Shah’s portrait can be seen in historical as well as factual characters in the illustrated manuscript of One Thousand and One Nights. The historical characters mainly belong to the Arab lands, though the story is factual. These characterizations which embody the personal traits of the historical characters were used to make the story more credible. In these stories, the king is characterized as a famous religious ruler. The artists consciously used this characterization strategy to arrange the illustration elements within a more purposeful discourse. By portraying the king as a strong and prosperous monarch, they aimed to support the discourse of monarchy.

Nasir al-Din Shah replaces, notably, three sovereigns in the illustrations: the first is the most famous ʿAbbasid caliph, Harun al-Rashid (r. 787-809) in “Muʿin the Vizier is Standing Before the King” (Night 35, vol. 1, fol. 145a), and “Caliph is Talking to Jaʿfar” (Night 44, vol. 1, fol. 177a). The second ruler is Alexander the Great (r. 336-356 B.C.), in “He is the King on a Trip to the Nature for Recreation” and “A Certain Tribe of Poor Folk” (both in Night 461, vol. 3, fol. 207a). The third monarch is Umar ibn ʿAbd al-ʿAziz ibn Marwan (r.717-720), the eighth Umayyad caliph, in “The Judge is Talking to King Nuʿman” (Night 78, vol. 1, fol. 241a).

The written sources recognize Harun al-Rashid as a powerful, wealthy and just king; Alexander the Great as wealthy, a powerful warrior and a conqueror; and ʿUmar ibn ʿAbd al-ʿAziz as a Just Ruler and Islam-oriented king. Our study presupposes such characteristics as being considered the essential elements of true kings. Alexander the Great and ʿUmar ibn ʿAbd al-ʿAziz do not play active roles as heroes in the tales; they only command their subjects to recite new stories; they are, though generally, considered as Just Rulers. Harun al-Rashid as well is not actively present in the tales, yet his imperceptible presence is predominant in the story. We see that the narrative is shadowed by a cloud of fear and horror attributed to Harun al-Rashid’s power, the fear that makes the two protagonists not daring to unite with one another. As a result, the narrative structure and this idea of the absolute king reinforce the cliché of Harun al-Rashid as the powerful figure.

While these historical characterizations are present within the manuscript, Nasir al-Din Shah more often replaces fictional kings and characters with no corresponding figures in the real world. In various scenes, Nasir al-Din Shah substitutes different kings, imbued with various meanings and symbols. Here we see a true work of artistic valor as the artist adorns the king with distinct qualities and personal traits in order to arrange the configuration of various discourses. Concerning the function of character in various stories, the analysis of the illustrations with the portrait of Nasir al-Din Shah shows two main groups: the passive king and the adventurous king.

The Passive King

In many of the tales the king is depicted as a passive ruler that lacks any exceptional characterization within the text. As a passive ruler, the king is presented only as being the ultimate figure of the state and a guarantee for its maintenance; he plays only an onomastic role. The illustrations depict the king in an ideal form that does not go beyond the conventional sense of being a king. Examples of such depictions include the king in the tale of “The Hunchback” (Nights 26-33, vol.1, fol. 90b-93b), King Nasir in the tale of “Al-Malik Nasir and the Three Chiefs of Police” (Nights 341-343, vol. 3, fol. 175a-176b), and King Pars in the tale of “Ebony Horse” (Nights 354-368, vol. 3, fol. 41a-57a).

In the first tale, the king (Malik) asks the convicts and the accused, who are from different guilds and religions, to narrate a story stranger than the one that occurred the previous night (i.e., the murder of the hunchback). If the king finds the stories attractive, he will forgive them; otherwise, the convicts are doomed to death. In the second tale, coming to the king to present reports, the governor (Wali) should recount the strangest events in his administrative division. If the king does not like the narration, the governor will either return to his division empty-handed or be removed from his position and power. In the third tale, three sages are asked to present their art and craft to the king. If the king finds them beautiful, they will be gifted with the opportunity to marry the princess.

Concerning the first and second tales, the king asks the other characters to narrate a story, which results in a series of entangled narrations whose end is to be decided by the king. The king asks others, mainly among his subordinates, to recount a story for him. If the king likes the story, the subordinate narrator will be either liberated from death punishment or given gifts. Otherwise, the narrator will be punished.

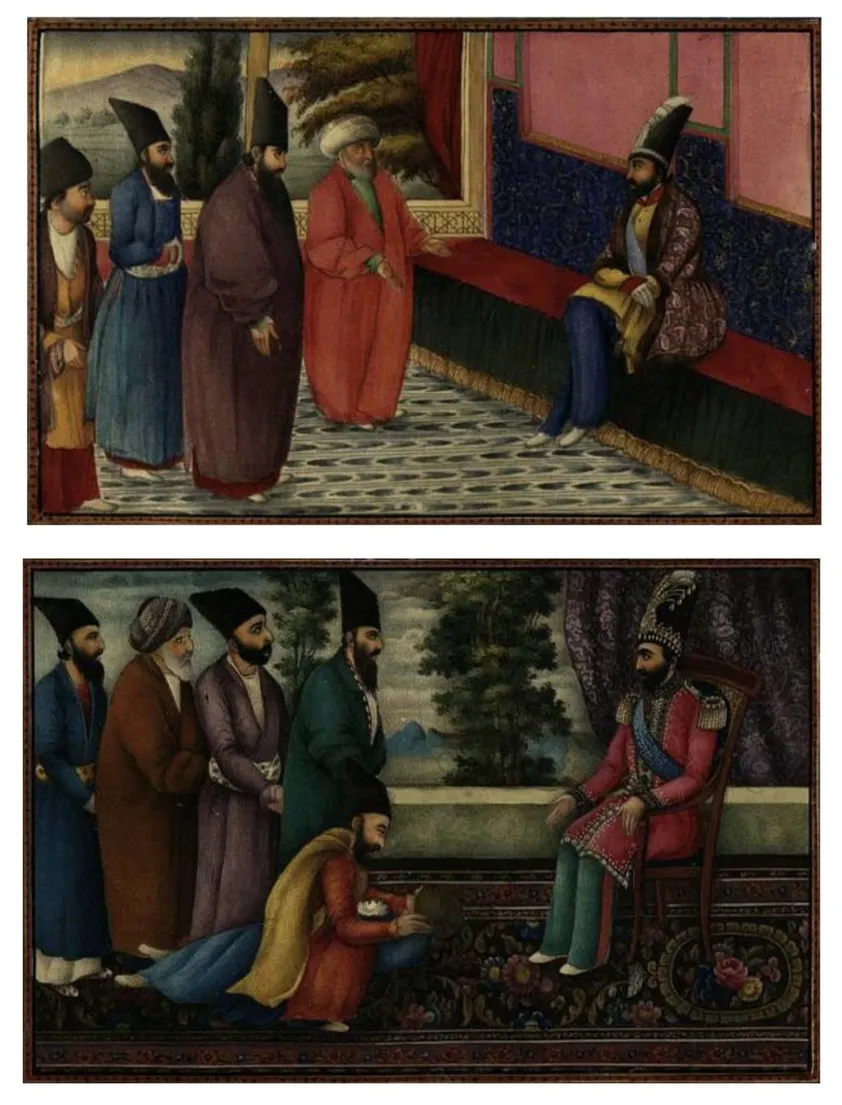

The two illustrations of the tale of “The Hunchback” depict Nasir al-Din Shah as the king who commands the story. It is about a tailor and his wife who invite a hunchback to dinner. The tailor places a large piece of fish into the hunchback’s mouth, making him choke. The tailor and his wife took the hunchback to a Jewish person. This later brings the hunchback to a Christian, and the Christian leaves him in the street to die, where finally, a night watchman finds him. The day after, all of the characters involved in the story are arrested and sent to the court in front of the king for the crime of killing the hunchback. The king asks them to narrate a story stranger than the tale of “The Hunchback” so he may spare their lives (fig. 1a). They each recount an event of their own lives, but the king does not appreciate those told by the Jewish or the Christian. However, the tailor takes his turn to tell a story about a talkative barber (Dallak) known as the Silent Sheikh. The king summons the Silent Sheikh to the court. After narrating his story, the Silent Sheikh notices the presumably dead Hunchback, puts his hand to his throat, and gets the fishbone out. The hunchback sneezes and comes back to life. The king forgives everyone (fig. 1b).8

The message of these tales and their illustrations is clear. Nasir al-Din Shah replaces the king in two sections; one in the middle of the tale, following the hunchback’s death when the king orders those involved to tell him their stories, and the other at the end when the hunchback comes back to life.

In both scenes, the king is sitting on the couch with attendees from different professions (the doctor, the tailor, the barber, the military administrator, and the governor) and different faiths (Islam, Judaism, and Christianity). They are all standing before the king in a humble manner. This posture is held for only a brief moment as the tale continues and several nights pass for the young king in these stories. The king (Nasir al-Din Shah in the illustration) is simply a listener, and the other characters recount their stories. Showing a keen interest in hearing new and innovative stories, the king is hidden behind a motionless and passive character despite being the initiator and producer of the story’s narrative. With this in mind, one must not forget that while passive, it is the king who holds the characters’ lives in his hands.

The position of the figures and their physical size, the replacement of the king with Nasir al-Din Shah, the use of characters from different guilds and religions before the king, and the depiction of the interior space in association with the infinite exterior space are strategies used by the artist to reproduce the concepts of guardianship (Wali Amr) of all religions and of all guilds, the discipline of affairs (in the form of courts), the domination of the world, and the royal will concerning the life and death of the masses, thus supporting the dominant discourse of monarchy (or Saltanat).

In the second story, the tale of “Malik Nasir and the Three Chiefs of Police,” the king, Malik Nasir, asks his governors in Cairo, Bulaq, and ancient Egypt to recount their strangest life events (fig. 2). Each governor tells a story, the quality of which determines whether or not they can keep their power and save their lives (Arabian Nights Encyclopedia 224-225).

Again, Nasir al-Din Shah takes the place of another king, whose name is Malik (king) Nasir. The painter made the best use of the phonological similarity between the two kings, as their names are Nasir. This strategy is frequently observed in the illustrations of One Thousand and One Nights; for instance, King Muhammad is portrayed as Muhammad Shah Qajar (Night 33, vol. 1, fol. 137a). Inhabiting a neutral character King Nasir (Nasir al-Din Shah in the illustration) invites the governors to narrate a story.

The artist attributes King Nasir’s qualities to Nasir al-Din Shah, and endeavours to recall the discourse of monarchy by portraying Nasir al-Din Shah as the Caliph and guardianship of all Muslims; he is the monarch of a vast country and still expands his kingdom and earthly domination. King Nasir represents the absolute sovereign of many governors (including those of Egypt), and his replacement with the actual Iranian king depicts the latter’s kingship. Nasir al-Din Shah is then an authoritative king with many yes-men, controlling a vast territory; an image which eventually concords with hegemonic monarchy discourse.

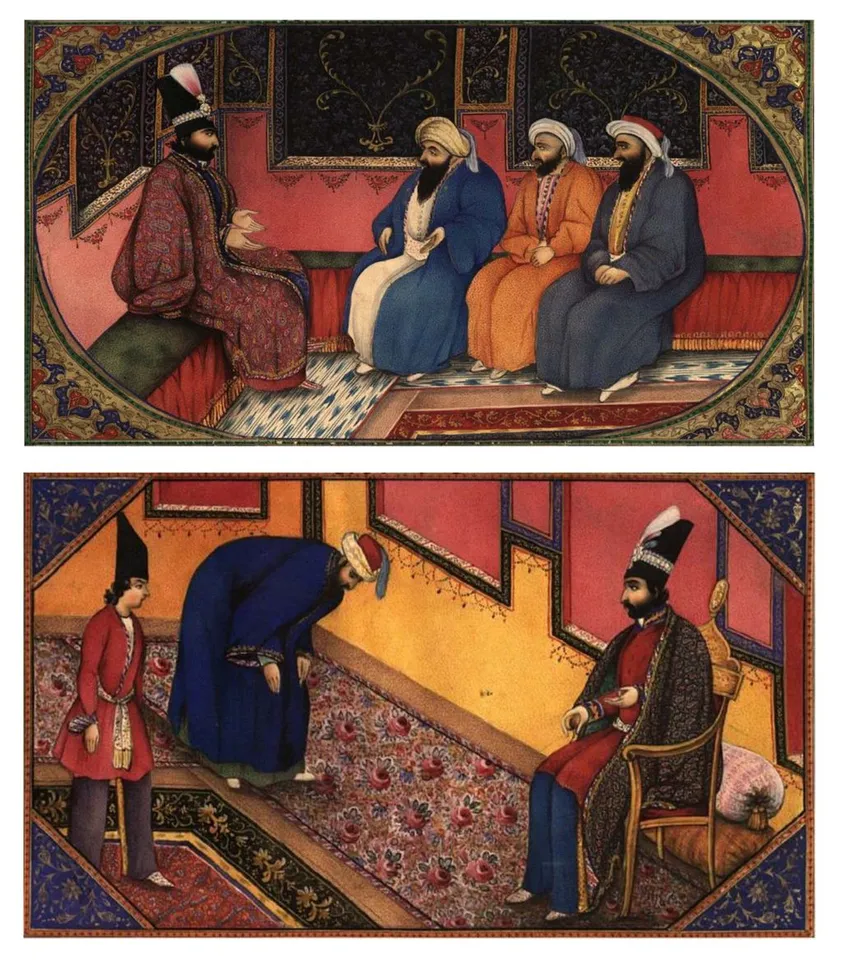

In the third tale, the tale of “Ebony Horse”, three sages are led before King Pars so they may show him their newest inventions; the most impressive of which will allow the respective sage the right to marry the king’s daughter. The first sage presents a golden peacock, which flaps its wings every hour (corresponding to the hour) and sings. The second sage has a silver trumpet that, if installed above the city gate, blows whenever an enemy enters the city. The king then gives the first and second sages some gifts and wages.

Afterwards, the third sage presents a horse of ebony that can fly and move the passenger to any location he wishes. The prince, in the presence of his father (Nasir al-Din Shah in the illustration), volunteers to test the horse (fig. 3). The horse moves into the air and returns. With the advent of this ebony horse, the love story of the king’s son begins (Arabian Nights Encyclopedia 172-174).

In this illustration, Nasir al-Din Shah is depicted as a king interested in scholars and inventions. The inventions are tools of various kinds, the most important of which is the ebony horse. The horse is the means by which the prince leaves his royal palace, marries another king’s daughter, and eventually returns. In other words, the horse is an evil symbol, on the one hand, as it removes the prince from his territory, and on the other, a good symbol as it allows him to marry a princess from another territory. Supposing the ebony horse is considered a symbol of modern technology, the prince’s trip can be understood as an attempt to expand the monarchical territory by allying with another kingdom or, in other words, adding other territories to Iran by using modern technologies. The illustrations seem to imply that deploying modern technology can guarantee the monarchy’s survival and the kingdom’s expansion.

As an alternative reading, the three sages can be seen as representatives of three major powers: Russia, England, and France. Within this reading, the peacock clock becomes a symbol of the clock gifted to Nasir al-Din Shah by Queen Victoria (r. 1837-1901) which was decorated with a statue of a peacock. The silver trumpet serves as a symbol of Russia that guaranteed the security and establishment of the Qajar dynasty in the Treaty of Turkmenchay (1828).

Finally, the ebony horse may symbolize France, a country believed to have sent many modern technologies, including military equipment, to 19th-century Iran. Both interpretations aim to redefine the discourse of monarchy through the bolstering of the narrative structures surrounding the ideas of an absolute king and royal marriage.

Showing the new inventions’ significance and the transition from traditional to modern technology, the artists also refer to the king’s prime minister, Amir Kabir’s political goals: deploying new tools and using the latest science and technology to expand knowledge in Iran. Amir Kabir was aware of the need for more scientific institutions in Iran and established Dar al-Funun (Polytechnic School) in 1851. New scientific principles such as engineering, medicine, pharmacy and mining were taught to young Iranians by several European instructors.

The Adventurous King

The illustrations associated with the tales of “Janshah” and “Taj al-Muluk and Dunya” depict the king as an active and influential figure, contrasting the passive attitude discussed above. The tale of “Janshah” narrates how the king of Kabul, Tighmus, although of advanced age, had no son to succeed him. Therefore, on the advice of his vizier, he married the daughter of the king of Khurasan. He prepared many gifts, which he sent to her by his viziers and deputies (fig. 4b); the new queen gave birth to a son, Janshah. (fig. 4a)

In this tale’s illustrations (Nights 496-527, vol. 3, fol. 272b-323a), Nasir al-Din Shah takes the role of two characters: the king of Kabul in eight illustrations, and his son, Prince Janshah, in one illustration. King Tighmus is described as an absolute king (padishah-i mutlaq) and a compassionate father who puts great effort into his son’s felicity. Prince Janshah is, in turn, a young and adventurous conqueror who finds his beloved wife on his brave journey and makes several conquests. When represented as Janshah, Nasir al-Din Shah is depicted as dynamic and active, readily accepting the pains and discomfort of the journey required to marry his beloved and finally achieving his goal after enduring great efforts and conflicts. On his journey, he succeeds in annexing other territories to his father’s kingdom, epitomizing a warrior and a hardworking and powerful king.

During a hunting expedition, Janshah finds himself lost on an island. Tighmus sends people to search the island, but in vain (fig. 4c). Upon their return to the king, we learn that Janshah has fallen in love with a fairy-born woman named Shamsa. She invited the prince to the Castle of the Jewels without giving him the address. The prince could marry Shamsa only if he could find the Castle. Janshah returns to his father and consults with him (fig. 4d); the king gathers the merchant, and they start looking for the Castle of the Jewels (Arabian Nights Encyclopedia 238-241) (fig. 4e).

At this point, the story shifts focus since the king of India, King Kafid, a long-time enemy of the king of Kabul, realizes that the latter is preoccupied with his son. Thus, King Kafid decides to retaliate by starting a war. King Tighmus consults with his viziers (fig. 4f) and writes a letter to King Kafid to dissuade him. Paying no attention to King Tighmus’s requests, King Kafid declares war with a coarse reply to King Tighmus’s letter (fig. 4g). After a series of magical tales, King Kafid and his troops are defeated, and Shamsa is found. King Kafid is brought as a captive to King Tighmus, but Shamsa, blessed by finding her love, asks for his forgiveness (fig. 4h-i). The two illustrations of the Indo-Iranian wars depict King Kafid kneeling before Nasir al-Din Shah, with his hands tied together, begging him for forgiveness. The Iranian king holds in his hands the life of the Indian one. The illustration shows the vast Indian territory dominated and controlled by Nasir al-Din Shah.

The exact date of these illustrations has yet to be determined. We can speculate, however, that they were completed sometime after 1857, when Iran agreed to withdraw from Herat, releasing Afghanistan from the control of the Iranian court. However, the illustrations may have been completed before the Treaty of Paris (1857) when Iran’s influence had already diminished in Afghanistan.9 In both cases, sovereignty over Afghanistan had been crucial for Iran. The replacement of the king of Kabul and his son and, within the framework of the manuscript, the king of Khurasan (a symbol of Iran) with Nasir al-Din Shah, can be seen as referring to Iran-Afghanistan relations and the Iranian king’s desire to maintain his power on the Eastern parts of his realm.

The illustrations that present Nasir al-Din Shah as an adventurous king, reviving the discourse of monarchy, also employ a specific structure called royal marriage. Within this framework, Nasir al-Din Shah takes the place of both the father and the son. We see the son expanding the kingdom by marrying a princess from another territory, emphasizing that he is a conqueror who expands his kingdom.

Through royal marriage, the artist also introduces Nasir al-Din Shah as the king of Iran and Afghanistan. The continuation of the monarchy throughout the marriage between Janshah and Shamsa and Janshah’s conquests enabled the painter to present Nasir al-Din Shah as the king of Iran and Afghanistan, endorsing the idea that their union guarantees the survival of the monarchy. These illustrations reproduce the discourse of monarchy by deploying the narrative structure of the true king and tropes such as the wealthy, noble and powerful monarch who ruled Iran and Afghanistan and also governed India.

In the continuity of the aforementioned concept of royal marriage, the second story in the illustrations of the Adventurous King is the tale of “Taj al-Muluk and Dunya” (Nights 107-157, vol. 1, 293a-357a). Here, the main character is a princess, Dunya, and Nasir al-Din Shah replaces all the central male figures. Besides showing the marriage between two royal families, the artist presents other essential issues, such as the male child becoming the crown prince, the expansion of the kingdom and conquests. We also see the love-making scenes between the King and the Princess, which recall the global conception of the royal marriage. This constitutes the King’s identity, prolongs his descendant, expands his kingdom, and accentuates the nobility embodied in the idea of his marriage with another royal family.

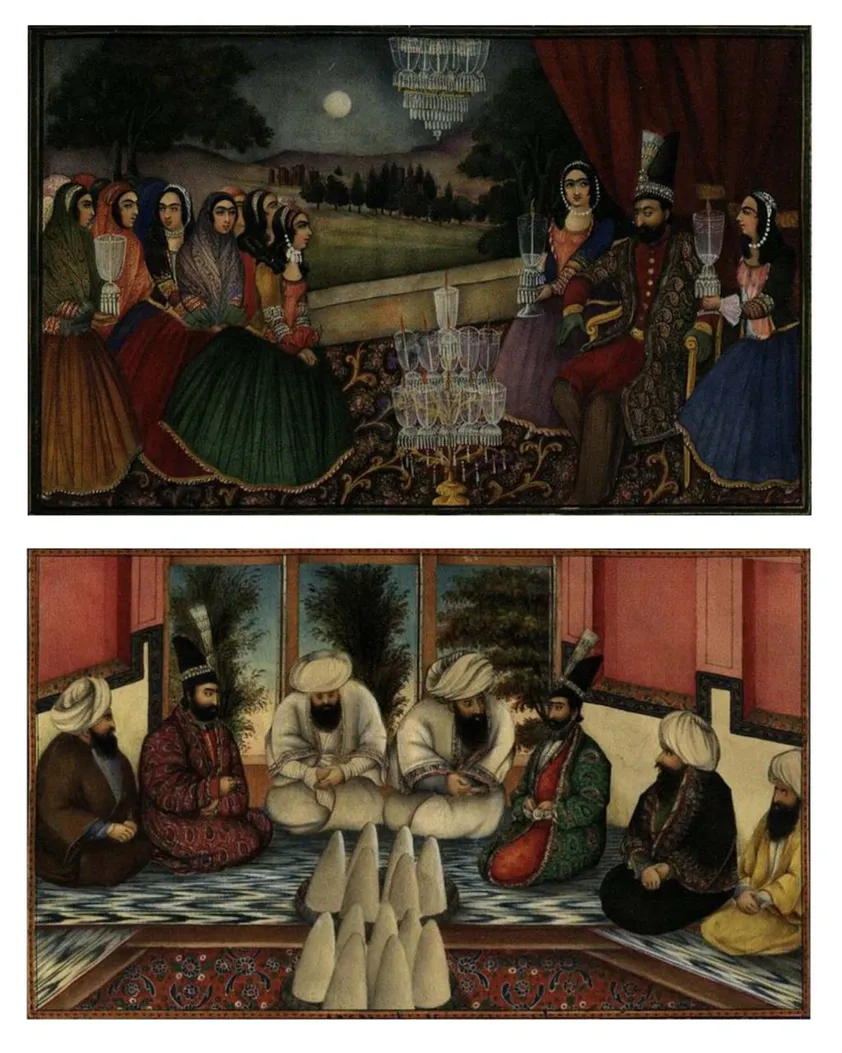

The story is about Suleyman Shah of the Green Land, a city near Isfahan, who wishes to have a noble wife and family. The Shah’s vizier advises him to marry the daughter of King Zahr Shah of the White Land. After the wedding, the king (Nasir al-Din Shah in the illustration) resides in the court to manage the affairs (fig. 5a). Soon after, the queen gives birth to a son named Taj al-Muluk. Having seen an image of Dunya, the daughter of King Shahriman of Waq Island, the young Taj al-Muluk falls in love with her. After a series of events, they get married. This advantageous marriage leads to Taj al-Muluk territory’s expansion and the monarchy’s continuation. In three instances, the artist substituted Nasir al-Din Shah’s portraits for the main characters: Taj al-Muluk, his father and his father-in-law. In one scene, we see Nasir al-Din Shah’s portrait twice since he represents both fathers of Taj al-Muluk and Dunya (Arabian Nights Encyclopedia 406-408) (fig. 5b).

In these illustrations, Sulayman Shah of the Green Land and King Shahriman of Waq Islands represent kingship in Iran and faraway countries or, in other words, the entire world. Taking the role of the father, the son, and the bride’s father, Nasir al-Din Shah, called in Qajar sources as Qiblah-i ʿAlam (Pivot of the Universe), brings faraway territories under his rule through royal marriage.

Of the three illustrations, two incorporate the images of marriage consummation and the birth of a child. The result of the marriage is a qualified prince who, as a successor, protects and expands the father’s kingdom. It should be remembered that the crisis of succession plagued Nasir al-Din Shah. The crown princes, born from a Qajar family and the official wives of Nasir al-Din Shah, were dying one after another after being appointed as the crown prince.10

Before the manuscript had been finished, three crown princes of Nasir al-Din Shah had already died, and Muzaffar al-Din Mirza was appointed as the crown prince. Therefore, the illustrations depicting the birth of a son or scenes of marriage consummation refer to the succession and the ensuing continuation of monarchy within the Qajar family. Using the narrative structure of royal marriage as the story’s foundation, the painter seemingly tries to allay Nasir al-Din Shah’s concern over the durability of the monarchy and expansion of the kingdom and gives him hope of calmness and success.

Moreover, Taj al-Muluk was, in fact, the daughter of Amir Kabir and ʿEzzat al-Dowla, Nasir al-Din Shah’s sister. Not soon after her birth, she got engaged to Muzaffar al-Din Mirza by order of the king’s mother. Although Muzaffar al-Din Mirza was not accepted seriously, since there were other sons in succession order, he was ultimately appointed Nasir al-Din Shah’s successor due to his brothers’ subsequent death. Muzaffar al-Din Mirza and Taj al-Muluk had three children by their marriage, including Muhammad ʿAli Mirza who became Muhammad ʿAli Shah in 1907.

Conclusion

The narrative structures observed in the illustrations prepare a suitable ground for producing the discourse of monarchy. Each discourse is itself a micro-discourse constituting the dominant discourse. Qajar Iran (1789-1925) was characteristically dominated by the absolute monarchy or kingship (Saltanat), with dissenting voices hardly being heard. Accordingly, the artist(s) of One Thousand and One Nights joined the dominant discourse by reproducing the ideas and concepts which reflected absolute monarchy.

Presenting Nasir al-Din Shah as Qiblah-i ʿAlam, the illustrations analysed in this article depict the king as dominating the people from different professions and religions. The king possesses power and wealth, and his nobility, legitimacy, protection of Islam, and justice place him in a position similar to early Islamic caliphs. Identifying Nasir al-Din Shah with Alexander the Great additionally depicts the king as a conqueror who expands his kingdom. In some cases, the royal marriage with a noble family from another territory leads to the continuation of the king’s monarchy and expansion of his kingdom, again presenting the king as a momentous conqueror through means not limited to war. Therefore, the illustrations discussed above portray Nasir al-Din Shah as a powerful king in all religious, political, economic, personal, and social terms.

The illustrations emphasize the values associated with the pillars of the monarchy and absolute rule while marginalizing oppositional, reformist discourse. The dominant discourse of the monarchy was constituted by the juxtaposition of signs pivoting around the focal signifier Nasir al-Din Shah; signs such as power, righteousness, security, wealth, the vast country, the legendary king, the conquest and expansion of the kingdom, nobility, legitimacy, the continuation of the State, the crown prince, territorial integrity, eternal luxurious life, royal marriage, and the guardianship of Muslims. Within this framework, Nasir al-Din Shah is the Pivot of the Universe. The world pivots around him focused on the institution of the royal court; the meaning system of this discourse reproduces the traditional conception of power. The authoritative king and absolute ruler are two elements foregrounded in the discourse of monarchy, and any other form of State and power is deemed illegitimate or illegal.

It is not unexpected to observe the reproduction of the discourse of monarchy by the court artists whose lives and living depended on their cooperation with the institution of monarchy. Given Nasir al-Din Shah’s interest in One Thousand and One Nights since his childhood, not only Saniʿ al-Mulk but also other agents involved, including Hussein ʿAli Khan Muʿayyir al-Mamalik (the steward or Mubashir), Soroush Isfahani (the poet), and ʿAbdul-Latif Tasouji (the translator), used the book in order to get closer to and to please this institution, thus reproducing the validity and arguments of the monarchy. Soroush’s grandiloquent poems on the lacquered cover of the manuscript and the last page of the printed illustrated version (1855) show his eagerness for the royal cause. Tasouji’s introduction is also full of glamorously laudatory remarks about the young king as the focal point of monarchy, highlighting his glory, forgiveness, wisdom, greatness, sagacity, and patronage of the arts.

Bibliography

Abd-Amin, Majid. Muraqqa-i Nasiri: tarahi-ha, siah mashgh-ha va yaddashtha-yi Nasir al-Din Shah. Mahmoud Afshar, 1398/2019.

Adamiyat, Fereydun. Amir Kabir va Iran. Kharazmi, 1969.

Al-Davoud, Seyyed Ali. Amir Kabir va Nasir al-Din Shah. Mahmoud Afshar, 2019.

Amanat, Abbas. “Court Patronage and Public Space: Abu’l-Hasan Sani’ al-Mulk and the Art of Persianizing the Other in Qajar Iran.” Court Cultures in the Muslim World: Seventh to Nineteenth Centuries, edited by Albrecht Fuess and Jan-Peter Hartung, 2011, pp. 408-444.

---. Qeble-ye ʿAlam. Karnameh, 2004.

Atabay, Badri. Fehrest-i divanha-yi khatti-yi ketabkhane-yi Saltanati va ketab-i Hezar-o-Yek-Shab (2 vols.). Gulistan Palace, 1976.

Bahman Mirza Qajar. Tazkera-i Muhammad Shahi. Tak Derakht, 2015.

Bakhtiar, Mozaffar. “Ketab aray-yi Hezar-u-Yek-Shab: noskhe-yi khatti-yi ketabkhane-yi Kakh-i Gulistan.” Name-yi Baharestan, vol. 3, no. 1, 2002, pp. 130-132.

Bamdad, Mehdi. Sharh-i hal-i rejal-i Iran dar qarn-i 12, 13, 14. Zavar, 1968-1972.

Boozari, Ali. “Noskhe-yi khatti-yi Hezar-u-Yek-Shab: noskhe-shenasi va moarrefi-yi negareha.” Name-yi Baharestan, no. 3, 2014, pp. 160–275.

Boozari, Ali and Maryam Shafiei. “Ta’mmoli bar barat-i divani dar llbom-i Beytoutat dar mozo-i makharej-i tolid-i noskhe-yi khatti-yi Hezar-u-Yek-Shab.” Ayine-yi Miras, vol. 19, no. 2, 2021, pp. 233-251.

Farmanfarmaian, Roxane. War and Peace in Qajar Persia: Implications Past and Present. Routledge, 2008.

Ghaziha, Fatemeh. Nasir al-Din Shah Qajar va Naqashi. The National Library and Archives of Iran, 2015.

Kazemzadeh, Firuz. “Anglo-Iranian Relations ii. Qajar period.” Encyclopaedia Iranica, online edition, http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/anglo-iranian-relations-ii. Accessed 29 Aug. 2023.

Marzolph, Ulrich. “The Persian Nights: Links between the Arabian Nights and Iranian Culture.” Fabula, vol. 45, no. 3/4, 2005, pp. 275-293.

Marzolph, Ulrich and Richard van Leeuwen. The Arabian Nights Encyclopedia. ABC-Clio, 2004.

Rettig, Simon. “Illustrating Firdawsi’s Book of Kings in the Early Qajar Era: The Case of the Ezzat-Malek Soudavar Shahnama.” Revealing the Unseen: New Perspectives on Qajar Art, edited by Gwenaëlle Fellinger and Melanie Gibson, Gingko, 2021, pp. 42-55.

Rizvi, Kishwar. “The Suggestive Portrait of Shah ʿAbbas: Prayer and Likeness in Safavid Shahnama.” Art Bulletin, vol. 94, no. 2, 2012, pp. 225-249.

Safari, Rouhollah. Judayi-i Harat: tarikh-i ravabet-i syiasi-yi Iran va Afghenstan dar asr-i Qajar. Shakib Gostar, 2015.

Tahmasbpour, Mohammad-Reza. Nasir al-Din, Shah-i akkas: piramoun-i tarikh-i akkasi-yi Iran (Nâser-od-din, the Photographer King). Tarikh-i Iran, 2008.

Yousefifar, Shahram. “Majmaʿ al-sanaiʿi (Tajruba-yi Nowgaray-i dar mashaghel-i kargah-ha-yi saltanati).” Ganjine-yi Asnad, vol. 21, pp. 42-64.

Zoka, Yahya. Zendegi va athar-i ustad Saniʿ al-Mulk, Mirza Abulhassan Khan-i Ghaffari, edited by Sirous Parham, Nashr-i Daneshgahi, 2003.